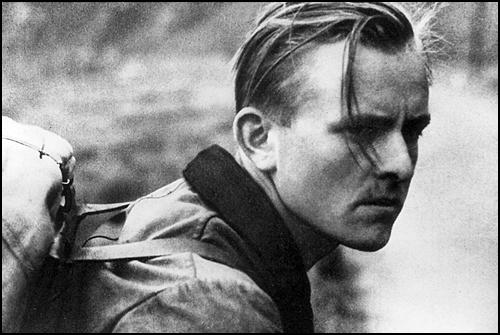

Willi Graf

Willi Graf, the son of the director of a wholesale wine business, was born in Kuchenheim, Germany, on 2nd January, 1918. It was claimed that his father demanded "correct and pious behaviour" and that his mother "provided the warmth and tenderness that softened this severity". (1)

Graf later wrote: "I spent my early life in the circle of my parents and sisters. I never felt deprivation of any kind, since our family lived in rather good, if moderate circumstances... The relationship with my mother was extremely affectionate. She did everything for her children. Her concern for her family was her whole life." (2)

In 1934 Graf joined the Catholic youth organisation, Graue Orden (Grey Order). He gradually became convinced that his Christian faith and fascism were incompatible. He did not join the Hitler Youth and refused to associate with children who did. (3)

Graf joined a group of young Catholics who called themselves "New Germany". In 1938 the Nazi government decided to abolish all youth groups that were in competition with the Hitler Youth. Graf was arrested and spent three weeks in "investigative custody". (4)

Willi Graf - Medical Student

After six months in the German Labour Service he became a medical student at the University of Bonn. In the summer of 1940 Graf was sent as a member of the medical corps that went with the German Army invading France. He later he took part in the occupation of Yugoslavia. Graf was appalled by the way the soldiers behaved towards civilians. He told his sister, Anneliese, "I wish I never had to see everything I've watched in these past days." In his diary he wrote: "To be a Christian, is perhaps the hardest thing to ever become in life." (5)

On his return he was sent to University of Munich for medical training. Soon afterwards he became friends with Alexander Schmorell, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst. They began meeting to discuss poetry. At meetings they took it in turns reading poems and the others had to guess the name of the poet. One evening, on 21st May, 1942, Hans read a poem about a tyrant that contained the passage: "Mounting the rubbish heap around him/He spews his message on the world." The people living under this tyrant accepted his rule: "The masses lived in utter shame/For foulest deeds they felt no blame." At the end, the poem predicts that this nightmare period will pass with the overthrow of the tyrant, and one day his reign will be looked back upon, and talked about, like the Black Plague.

No one at the meeting could identify the poet. Probst suggested that it had been written in Germany recently. "Anyway, those verses couldn't be more timely. They might have been written yesterday." Schmorell agreed and suggested that the poem should be mimeographed and dropped over Germany from an airplane "with a dedication to Adolf Hitler". Graf added that it should be printed in the Völkischer Beobachter. Scholl then told the group the name of the poet was Gottfried Keller. "Actually, the verses were written in 1878, and they don't refer to events in Germany at all, but to a political situation in Switzerland. The author is Gottfried Keller". (6)

After this the meetings tended to be more political and the members discussed ways they could show their disapproval of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. As Anton Gill, the author of An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler (1994) has pointed out: "The group had no wish to throw bombs, or to cause any injury to human life. They wanted to influence people's minds against Nazism and militarism." (7)

White Rose Group

The friends became known as the White Rose group. Hans Scholl soon emerged as the group's leader: "The role was tacitly bestowed on him by virtue of that quality in his personality that, in any group, made him the focus of attention. Alex Schmorell was usually at his side, his close collaborator. Between them, they arranged for meetings and meeting places.... Sometimes they met in Hans' room for impromptu talk and discussion. For larger meetings, they gathered at the Eickemeyer studio or the villa of Dr. Schmorell, an indulgent father who shared many of his son's views." (8)

Over the next few weeks Sophie Scholl, Jugen Wittenstein, Traute Lafrenz and Gisela Schertling became active members. Inge Scholl, Hans and Sophie's sister, who lived in Ulm, also attended meetings whenever she was in Munich. "There was no set criterion for entry into the group that crystallized around Hans and Sophie Scholl... It was not an organization with rules and a membership list. Yet the group had a distinct identity, a definite personality, and it adhered to standards no less rigid for being undefined and unspoken. These standards involved intelligence, character, and especially political attitude." (9)

Leaflet Campaign

In June 1942 the White Rose group began producing leaflets. They were typed single-spaced on both sides of a sheet of paper, duplicated, folded into envelopes with neatly typed names and addresses, and mailed as printed matter to people all over Munich. At least a couple of hundred were handed into the Gestapo. It soon became clear that most of the leaflets were received by academics, civil servants, restaurateurs and publicans. A small number were scattered around the University of Munich campus. As a result the authorities immediately suspected that students had produced the leaflets. (10)

The opening paragraph of the first leaflet said: "Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be "governed" without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today every honest German is ashamed of his government. Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes - crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure-reach the light of day? If the German people are already so corrupted and spiritually crushed that they do not raise a hand, frivolously trusting in a questionable faith in lawful order in history; if they surrender man's highest principle, that which raises him above all other God's creatures, his free will; if they abandon the will to take decisive action and turn the wheel of history and thus subject it to their own rational decision; if they are so devoid of all individuality, have already gone so far along the road toward turning into a spiritless and cowardly mass - then, yes, they deserve their downfall." (11)

According to the historian of the resistance, Joachim Fest, this was a new development in the struggle against Adolf Hitler. "A small group of Munich students were the only protesters who managed to break out of the vicious circle of tactical considerations and other inhibitions. They spoke out vehemently, not only against the regime but also against the moral indolence and numbness of the German people." (12) Peter Hoffmann, the author of The History of German Resistance (1977) claimed they must have been aware that they could do any significant damage to the regime but they "were prepared to sacrifice themselves" in order to register their disapproval of the Nazi government. (13)

Willie Graf was a respected member of the White Rose group. Sophie Scholl explained: "When he says anything, in his very deliberate way, one has the impression that he would not speak unless he could commit himself with his whole being. That's why everything about him gives the impression of being precise, genuine, and wholly reliable." Inge Scholl added: "Willie Graf, a tall, blond boy from the Saar region. He was rather taciturn fellow, thoughtful and reserved. When Hans got to know him, it was immediately evident that Willie belonged with them. He was occupied intensely with problems of philosophy and theology." (14)

At the end of July, 1942, Willie Graf, Hans Scholl, and Alexander Schmorell, were sent to the Eastern Front as medics. During their time in Poland and the Soviet Union they witnessed many examples of atrocities being committed by the German Army which made them even more hostile to the government. They were also upset by having to treat so many wounded and dying soldiers. It became clear that Germany was fighting a war it could not win. (15)

Willie Graf was very disturbed by what he witnessed in the Soviet Union. As a soldier in a combat zone, he had expected to encounter wounds and death. He had been prepared for that. However, he was shocked and appalled by the way that civilians and captured members of the Red Army had been treated. He wrote to his sister: "The war here in the East leads to things so terrible I would never have thought them possible... Some things have occurred... that have disturbed me deeply... I can't begin to give you the details... It is simply unthinkable that such things exist... I wish I hadn't had to see what I have seen.... I could tell you much more but do not want to trust it to a letter." (16)

A friend commented: "Willie Graf... was one of those young people who have always found it impossible to remain indifferent in the face of injustice." He wrote in his journal: "Sometimes, I am certain of the rightness of my course. Sometimes I doubt it. But I take it upon myself nevertheless, no matter how burdensome it may be." Graf told his sister Annaliese that for him the most important thing was simply the preservation of "the world that shaped our culture and our life." (17)

Graf, Scholl and Schmorell returned to Munich in November, 1942. The following month Scholl went to visit Kurt Huber and asked his advice on the text of a new leaflet. He had previously rejected the idea of leaflets because he thought they would have no appreciable effect on the public and the danger of producing them outweighed any effect they might have. However, he had changed his mind and agreed to help Scholl write the leaflet. (18) Huber later commented that "in a state where the free expression of public opinion is throttled a dissident must necessarily turn to illegal methods." (19)

A Call to All Germans!

The first draft of the fifth leaflet was written by Sophie and Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell. (20) Kurt Huber then revised the material. The three men had long discussions about the content of the leaflet. Huber thought that the young men were "leaning too much to the left" and he described the White Rose group as "a Communist ring". (21) However, it was eventually agreed what would be published. For the first time, the name White Rose did not appear on the leaflet. The authors now presented them as the "Resistance Movement in Germany". (22)

This leaflet, entitled A Call to All Germans!, included the following passage: "Germans! Do you and your children want to suffer the same fate that befell the Jews? Do you want to be judged by the same standards as your traducers? Are we do be forever the nation which is hated and rejected by all mankind? No. Dissociate yourselves from National Socialist gangsterism. Prove by your deeds that you think otherwise. A new war of liberation is about to begin."

It ended with the kind of world they wanted after the war finished: "Imperialistic designs for power, regardless from which side they come, must be neutralized for all time... All centralized power, like that exercised by the Prussian state in Germany and in Europe, must be eliminated... The coming Germany must be federalistic. The working class must be liberated from its degraded conditions of slavery by a reasonable form of socialism... Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the protection of individual citizens from the arbitrary will of criminal regimes of violence - these will be the bases of the New Europe." (23)

The Gestapo later estimated that the White Rose group distributed around 10,000 copies of this leaflet. Sophie Scholl and Traute Lafrenz purchased the special paper needed, as well as the envelopes and stamps from a large number of shops to avoid suspicion. Each leaflet was turned out one by one, night after night. "In order to stay awake and to function during the day, they took pep pills from the military clinics where the medics worked." (24) The conspirators had to ensure that the Gestapo could not trace the source to Munich so the group had to post their leaflets from neighbouring towns." (25)

On 21st January 1943, Willie Graf took a suitcase of leaflets to Cologne and Bonn where he gave out copies to friends to distribute. The following day he went to Saarbrücken to meet with Heinrich Bollinger at the military hospital where he worked as a medic. Bollinger agreed to use his duplicating machine to reproduce more leaflets. After that he travelled to Freiburg and Ulm with his suitcase of leaflets before arriving back in Munich. "It was a long trip; it meant many train connections, many chances to be checked; his suitcase had been a ticking bomb." (26)

The authorities took the fifth leaflet more seriously than the others. One of the Gestapo's most experienced agents, Robert Mohr, was ordered to carry out a full investigation into the group called the "Resistance Movement in Germany". He was told "the leaflets were creating the greatest disturbance at the highest levels of the Party and the State". Mohr was especially concerned by the leaflets simultaneous appearance in widely separated cities including Stuttgart, Vienna, Ulm, Frankfurt, Linz, Salzburg and Augsburg. This suggested an organization of considerable size was at work, one with capable leadership and considerable resources. (27)

On 3rd, 8th and 15th February, 1943, Willi Graf, Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell went out into the darkened streets and painted slogans such as "Freedom" and "Down with Hitler!" on the walls of apartment houses, state buildings, and the university. In some places they added a white swastika, crossed out with a smear of red paint. Christoph Probst, who was living in Innsbruck at the time, heard about this, he told his friends that "these nocturnal forays were dangerous and foolish." (28)

On 18th February, Sophie and Hans Scholl went to the University of Munich with a suitcase packed with leaflets. According to Inge Scholl: "They arrived at the university, and since the lecture rooms were to open in a few minutes, they quickly decided to deposit the leaflets in the corridors. Then they disposed of the remainder by letting the sheets fall from the top level of the staircase down into the entrance hall. Relieved, they were about to go, but a pair of eyes had spotted them. It was as if these eyes (they belonged to the building superintendent) had been detached from the being of their owner and turned into automatic spyglasses of the dictatorship. The doors of the building were immediately locked, and the fate of brother and sister was sealed." (29)

Jakob Schmid, a member of the Nazi Party, saw them at the University of Munich, throwing leaflets from a window of the third floor into the courtyard below. He immediately told the Gestapo and they were both arrested. They were searched and the police found a handwritten draft of another leaflet. This they matched to a letter in Scholl's flat that had been signed by Christoph Probst. Following interrogation, they were all charged with treason. (30)

Arrest & Execution

Willie Graf, Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber were arrested soon afterwards. The Gestapo interviewed Graf for several days and nights. He willingly admitted his guilt but refused to give the names of other members of the White Rose group. It was later claimed that "brilliant lights were beamed into his eyes constantly as three voices questioned him in irregular, unpredictable patterns". (31)

Willie Graf was put on trial with other members of the White Rose plus those who had helped the group on 19th April, 1943. This included Alexander Schmorell, Kurt Huber, Traute Lafrenz, Hans Hirzel, Susanne Hirzel, Falk Harnack, Eugen Grimminger, Heinrich Bollinger, Helmut Bauer, Franz Müller, Heinrich Guter, Gisela Schertling and Katharina Schüddekopf. (32)

Graf along with Schmorell was charged with high treason. The indictment stated that Graf should "have been particularly grateful to the Führer, for he ordered army pay for them during the time of their university attendance - as was true for all enlistees assigned to medical study. Inclusive of money for food, they received over 250 marks per month, and exclusive of money for food, but with rations in goods, it still amounted to about 200 marks - more than most students ordinarily receive from home". He was accused of distributing leaflets and recruiting others "for anti-German projects". (33)

Willi Graf said almost nothing in his defence when he appeared in the dock. Judge Roland Freisler told Graf that he "had the Gestapo running in circles for a while... but in the end we were too smart for you, weren't we?" (34) "Graf stood tall, pale, his features closed, his blue eyes remote". When he refused to answer questions Freisler ordered him to leave the dock. "Graf sat down, his eyes blank; it was as if his spirit had left the chamber." (35)

Willie Graf, Kurt Huber and Alexander Schmorell were all convicted of high treason and were all sentenced to death. Huber and Schmorell were both executed on 13th July, 1943. However, Graf was kept alive as they hoped he would provide information on other members of the White Rose network. They offered to change the verdict in exchange for information. When he refused they made threats against his family. (36)

While in prison he wrote a letter to his parents: "What hurts me most of all is that I am causing such pain to those of you who go on living. But strength and comfort you'll find with God and that is what I am praying for till the last moment. I know that it will be harder for you than for me. I ask you, Father and Mother, from the bottom of my heart, to forgive me for the anguish and the disappointment I've brought you. I have often regretted what I've done to you, especially here in prison. Forgive me and always pray for me! Hold on to the good memories.... I could never say to you while alive how much I loved you, but now in the last hours I want to tell you, unfortunately only on this dry paper, that I love all of you deeply and that I have respected you. For everything that you gave me and everything you made possible for me with your care and love. Hold each other and stand together with love and trust.... God's blessing on us, in Him we are and we live." (37)

Willie Graf was executed on 12th October, 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) Annette Dumbach & Jud Newborn, Sophie Scholl and the White Rose (1986)

Willi Graf was a latecomer to the group, the last to join before Sophie arrived. He was also the outsider; no matter how deeply he was to become involved in the conspiracy, no matter how perilous the acts he was to commit, there always remained a sense of distance between him and the others.

Unlike the others, Willi was an intensely devout Catholic, a silent, brooding young man who put his faith to test constantly. His taciturnity and lack of social grace disguised the fact that he was tormented by doubts - in himself, in the notion of resistance in wartime, and sometimes, perhaps, in some secret and terrible place in his heart, even in God himself.

(2) Richard F. Hanser, A Noble Treason: The Story of Sophie Scholl (1979)

Willi Graf was another one whose coming together with Hans Scholl was inevitable, and when they did meet, Hans' remark to Alex Schmorell afterward was "He's one of us." And Willi did become one of them-to the end. He kept a diary, and already, before he knew the way that he would go, he had written in it: "Sometimes you can't just go where favoring winds send you. Sometimes one must take a direction which isn't that easy. You can't allow yourself to be continually blown about." With his meeting with Hans Scholl, Willi Graf's life took a new direction, though it would be some time before he was aware of it.

To allow himself to be blown about was never Willi Graf's style. As a boy of fifteen, he resisted joining the Hitler Youth because something in him rebelled at being dragooned into an organization for which he had no sympathy. He regarded the Nazi insistence on lockstep conformity as an affront to his self-respect. He kept an address book of his neighborhood friends, and at the height of the Hitler Youth enthusiasm, he began crossing out names with the notation: "Joined HY" He could not be intimidated by the roving street gangs of young Hitlerites, and he gave as good as he got when attacked for his nonconformity.

Willi Graf's allegiance could not be coerced, but when it was freely given it endured. He joined a group of young Catholics who called themselves "New Germany", and for the rest of his life his social and fraternal loyalities were bound up with his religious convictions, which were strong and deep. In the wave of arrests in r938, when the Secret State Police sought to break up all associations of the young except the Hitler Youth, Willi Graf spent three weeks in "investigative custody". As with Hans Scholl, the indignity of being jailed and imprisoned without legitimate cause hardened an already settled antagonism to the National Socialist system. Willi Graf never gave up his membership in New Germany, though it remained under permanent ban by the Secret State Police.

(3) Reich Attorney General, indictment of Willie Graf (21st February, 1943)

Graf, who collaborated treasonously and in aid of the enemy to almost the same degree as Schmorell and Scholl. Both had been assigned by the armed services to the study of medicine. Both ought to have been particularly grateful to the Führer, for he ordered army pay for them during the time of their university attendance - as was true for all enlistees assigned to medical study. Inclusive of money for food, they received over 250 marks per month, and exclusive of money for food, but with rations in goods, it still amounted to about 200 marks - more than most students ordinarily receive from home. Both were sergeants, both were assigned to student companies...

When Graf, on the advice of Scholl, decided to use a trip to the Rhineland to sound out the opinions of acquaintances in the university towns of Bonn and Freiburg - and to recruit them for anti-German projects - he intended to meet Bollinger in Freiburg, but learned that the latter had gone to Ulm. There he sought him out, and the two of them visited Bollinger's acquaintances. With these people they did not discuss politics, but late at night, as Bollinger was seeing Graf off at the railroad station, Graf told him about the ideas and plans of the Scholl circle in Munich. Graf's attempts to recruit this man were unsuccessful, but apparently he gave him a copy of a leaflet, which Bollinger shortly there after showed to his friend, the accused Bauer, as well as to an acquaintance in the "Neues Deutschland" group ! He did so, not in order to recruit, but to let Bauer know about Bollinger's conversation with Graf. Bollinger and Bauer were in agreement about their rejection of the leaflet and the entire Scholl action.

(4) Völkischer Beobachter (21st April, 1943)

The People's Court of the German Reich, in session in Munich, dealt with a number of accused persons who were involved in the high treason of the brother and sister Scholl sentenced on February 22, 1943.

At the time of the arduous struggle of our people in the years 1942-43, Alexander Schmorell, Kurt Huber, and Wilhelm Graf of Munich collaborated with the Scholls in calling for sabotage of our war plants and spreading defeatist ideas. They aided the enemy of the Reich and attempted to weaken our armed security. These accused, having through their violent attacks against the community of the German people voluntarily excluded themselves from that community, were punished by death. They have forfeited their rights as citizens forever.

Eugen Grimminger of Stuttgart furnished funds in support of this action, though, to be sure, he was not fully aware of its details. The Court was unable to establish that he consciously gave aid to the enemy of the Reich. Furthermore, he gave considerable assistance to his employees who were serving in the armed forces, though on the other hand he was aware that the money might be used for purposes injurious to the state. He has been sentenced to ten years in jail. Heinrich Bollinger and Helmut Bauer of Freiburg had knowledge of the treasonous acts of the above-named accused but failed to report them, despite the fact that they are mature adults, and in contravention of the obligation of every German to make report of treasonous plans of this sort. In addition, they listened to enemy broadcasts. They have been sentenced to seven years in jail, and they have forfeited their honor as citizens for the same length of time.

Hans Hirzel and Franz Müller of Ulm, immature youths, aided in the distribution of the treasonous leaflets. In consideration of their youth they were sentenced to five years' imprisonment.The accused Heinrich Guter of Ulm, likewise a young person who knew of the treasonous acts but failed to report them, was sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment. Three girls who were guilty of the same act were sentenced to one year's imprisonment.

One other accused person, who assisted in the distribution of the leaflets but who did not know their contents, was given a sentence of six months in jail because she failed to carry out her obligation to inform herself about the contents of the leaflets.

(5) Willie Graf, letter to his parents (12th October, 1943)

On this day I'm leaving this life and entering eternity. What hurts me most of all is that I am causing such pain to those of you who go on living. But strength and comfort you'll find with God and that is what I am praying for till the last moment. I know that it will be harder for you than for me. I ask you, Father and Mother, from the bottom of my heart, to forgive me for the anguish and the disappointment I've brought you. I have often regretted what I've done to you, especially here in prison. Forgive me and always pray for me! Hold on to the good memories.... I could never say to you while alive how much I loved you, but now in the last hours I want to tell you, unfortunately only on this dry paper, that I love all of you deeply and that I have respected you. For everything that you gave me and everything you made possible for me with your care and love. Hold each other and stand together with love and trust.... God's blessing on us, in Him we are and we live.... I am, with love always,

Student Activities

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)