On this day on 13th September

On this day in 1521 William Cecil, he son of Richard Cecil and Jane Heckington Cecil, was born in Bourne, Lincolnshire. His father served as page of the chamber to Henry VII. Later he won promotion as groom and then yeoman of the wardrobe. He leased crown lands and advanced the family's local standing and served as sheriff of Rutland.

Cecil was educated in local grammar schools in Stamford and Grantham. He entered St John's College in 1535. While at Cambridge University he became friends with Matthew Parker, Roger Ascham, John Cheke and Nicholas Bacon. They all became interested in the Protestant religion. Six years later without taking a degree. He then moved on to Gray's Inn in 1541.

While at university William Cecil fell in love with John Cheke's sister, Mary Cheke. His father objected to the relationship as her father had been a college beadle and her mother ran a wine shop. In spite of the family opposition, William married Mary in August 1541. The following year she gave birth to their only child, Thomas. She died in February 1543.

Richard Cecil used his influence to obtain his son the post of chief clerk of the court of common pleas, worth £250 a year. In 1544 John Cheke became tutor to Prince Edward and Roger Ascham became tutor to Princess Elizabeth. With influential friends at Court, the 25-year-old Cecil was able to make a good marriage in 1545 to 20-year-old Mildred Cooke, the eldest daughter of Sir Anthony Cooke. Soon afterwards he began working for Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset.

Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. His son, Edward, was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist the young king in governing his new realm. It was not long before his uncle, Edward Seymour emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. To increase his power he secretly married Edward's stepmother, Catherine Parr.

In 1548 Cecil became Somerset's private secretary. (7) Somerset was a Protestant and he soon began to make changes to the Church of England. This included the introduction of an English Prayer Book and the decision to allow members of the clergy to get married. Attempts were made to destroy those aspects of religion that were associated with the Catholic Church, for example, the removal of stained-glass windows in churches and the destruction of religious wall-paintings. Somerset made sure that Edward VI was educated as a Protestant, as he hoped that when he was old enough to rule he would continue the policy of supporting the Protestant religion.

Somerset's programme of religious reformation was accompanied by bold measures of political, social, and agrarian reform. Legislation in 1547 abolished all the treasons and felonies created under Henry VIII and did away with existing legislation against heresy. Two witnesses were required for proof of treason instead of only one. Although the measure received support in the House of Commons, its passage contributed to Somerset's reputation for what later historians perceived as his liberalism.

Popular rebellions and riots began in the west of England in 1548 and spread through more than half the counties of England over the next few months. Some of those involved demonstrated against Somerset's religious programme. "The new vernacular liturgy contained in the Book of Common Prayer was the most evident grievance of the Cornish rebels, but the other religious changes of recent years and opposition to enclosures were also important. Revolt began in Cornwall in April 1548 when the clergy and commoners resisted the removal of religious images from parish churches and killed a government official, while in Somerset weavers and other commoners pulled down hedges and fences."

Edward Seymour urged compassion and on 14th June 1549, he persuaded Edward VI to pardoned all those people who had torn down hedges enclosing common land. Many landless people thought that this meant that their king disapproved of enclosures. All over the country people began to destroy hedges that landowners had used to enclose common land.

As Roger Lockyer, the author of Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985), pointed out: "Somerset's championship of the common people won him their acclaim. It also promoted them to demonstrations which were designed to show their support for him, but which quickly developed into massive protest movements that no government could have tolerated or ignored."

Edward Seymour was blamed by the nobility and gentry for the social unrest. They believed his statements about political reform had encouraged rebellion. His reluctance to employ force and refusal to assume military leadership merely made matters worse. Seymour's critics also disliked his popularity with the common people and considered him to be a potential revolutionary. His main opponents, including John Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick, Henry Wriothesley, 2nd Earl of Southampton, Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, Nicholas Wotton and Ralph Sadler met in London to demand his removal as Lord Protector.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer supported the Duke of Somerset but few others took his side. Seymour no longer had the support of the aristocracy and had no choice but to give up his post. His deposition as lord protector was confirmed by act of parliament, and he was also deprived of all his other positions, of his annuities, and of lands to the value of £2,000 a year. As Somerset's private secretary Cecil was arrested in November 1549 and sent to the Tower of London.

In January 1550, John Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick, who was now the most powerful figure in the government, ordered his release. Warwick recognised Cecil's talents as an administrator and by September he was a Privy Councillor. A few weeks later Cecil was asked to write a paper on Emperor Charles V and the dangers of a military invasion. In the document he argued: "The emperor is aiming at the sovereignty of Europe, which he cannot obtain without the suppression of the reformed religion; and unless he crushes the English nation, he cannot crush the reformation. Besides religion, he has a further quarrel with England, and the Catholic party will leave no stone unturned to bring about our overthrow. We are not agreed among ourselves. The majority of our people will be with our adversaries." Cecil was making the point that the people may have acquiesced in the religious changes that had taken place but they had by no means approved of them.

William Cecil was invited by Princess Elizabeth to become her surveyor (estate manager) at a salary of £20 a year. Roger Ascham commented: "William Cecil... a young man, indeed, but mature in wisdom, and so deeply skilled, both in letters and affairs, and endued with such moderation in the exercise of public offices."

It is claimed by Richard Rex that Elizabeth had recognised his administrative abilities. "In 1550 the lands which were rightfully hers under her father's will were at last made over to her as she approached adulthood, and it was probably in this context that she shrewdly appointed William Cecil as her surveyor... even more shrewdly allowing him to appoint a deputy to discharge his duties, leaving him merely to draw a handy fee."

John Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick, became the king's main adviser and in October 1551 he was granted the title, Duke of Northumberland. It has been claimed that the secret of his power was that he took the young king seriously. To be successful he "knew that he must accommodate the boy's keen intelligence and also his sovereign will". By this time the king clearly "possessed a powerful sense that he and not his council embodied royal authority". However, foreign observers did not believe that Edward was making his own decisions. The French ambassador reported that "Northumberland visited the King secretly at night in the King's Chamber, unseen by anyone, after all were asleep. The next day the young Prince came to his council and proposed matters as if they were his own; consequently, everyone was amazed, thinking that they proceeded from his mind and by his invention." Dale Hoak agrees and suggests that "Northumberland was skillfully guiding the king for his own purposes by exploiting the boy's precocious capacity for understanding the business of government."

William Cecil was now considered one of the most important of Northumberland's advisers and was rewarded by being knighted on 11th October 1551. His biographer, Wallace T. MacCaffrey, has pointed out: "Cecil was kept busy with routine tasks but he cultivated the career possibilities of the office, establishing wide contacts, particularly with protestant humanists at home or serving abroad as diplomats. He moved in a circle which mingled clergy of the reformed persuasion with sympathetic laity."

King Edward VI died on 6th July, 1553. The Duke of Northumberland attempted to take power by placing Lady Jane Grey on the throne. Mary fled to Kenninghall in Norfolk. As Ann Weikel has pointed out: "Both the earl of Bath and Huddleston joined Mary while others rallied the conservative gentry of Norfolk and Suffolk. Men like Sir Henry Bedingfield arrived with troops or money as soon as they heard the news, and as she moved to the more secure fortress at Framlingham, Suffolk, local magnates like Sir Thomas Cornwallis, who had hesitated at first, also joined her forces."

William Cecil initially supported Northumberland and organized a meeting at the Tower of London on 19th July of senior figures in the government. Cecil was forced to sign the document changing the order of succession (cutting out Mary and Elizabeth in favour of Lady Jane), but he was unhappy about it and made sure he had witnesses to his misgivings. However, aware that the conflict might result in civil war and that foreign powers would probably intervene. He therefore decided to support Mary.

Richard Rex argues that this development had consequences for her sister, Elizabeth: "Once it was clear which way the wind was blowing, she (Elizabeth) gave every indication of endorsing her sister's claim to the throne. Self-interest dictated her policy, for Mary's claim rested on the same basis as her own, the Act of Succession of 1544. It is unlikely that Elizabeth could have outmanoeuvred Northumberland if Mary had failed to overcome him. It was her good fortune that Mary, in vindicating her own claim to the throne, also safeguarded Elizabeth's."

The problem for Dudley was that the vast majority of the English people still saw themselves as "Catholic in religious feeling; and a very great majority were certainly unwilling to see - King Henry's eldest daughter lose her birthright." When most of Dudley's troops deserted he surrendered at Cambridge on 23rd July, along with his sons and a few friends, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London two days later. Tried for high treason on 18th August he claimed to have done nothing save by the king's command and the privy council's consent. Mary had him executed at Tower Hill on 22nd August. In his final speech he warned the crowd to remain loyal to the Catholic Church.

William Cecil declined offers to serve in Mary's government. He was unwilling to be the executor of Catholic policy, but he remained on good terms with the new regime. In 1554 he agreed to visit Italy in a mission to bring Cardinal Reginald Pole to England. Later he attended Pole in a secretarial capacity in an attempted mediation between the Emperor Charles V and France.

In the summer of 1558 Queen Mary began to get pains in her stomach and thought she was pregnant. This was important to Mary as she wanted to ensure that a Catholic monarchy would continue after her death. It was not to be. Mary had stomach cancer. Mary now had to consider the possibility of naming Elizabeth as her successor. "Mary postponed the inevitable naming of her half-sister until the last minute. Although their relations were not always overtly hostile, Mary had long disliked and distrusted Elizabeth. She had resented her at first as the child of her own mother's supplanter, more recently as her increasingly likely successor. She took exception both to Elizabeth's religion and to her personal popularity, and the fact that first Wyatt's and then Dudley's risings aimed to install the princess in her place did not make Mary love her any more. But although she was several times pressed to send Elizabeth to the block, Mary held back, perhaps dissuaded by considerations of her half-sister's popularity, compounded by her own childlessness, perhaps by instincts of mercy." On 6th November she acknowledged Elizabeth as her heir.

Mary died, aged forty-two, on 17th November 1558. On the first day of her reign Queen Elizabeth appointed William Cecil as her Secretary of State. He was thirty-eight, "quiet, formidable, with a spare frame and clear, pale eyes in a forehead oppressed by care... his talents were extraordinary not so much in kind as in degree; he had the abilities of the professional man, raised to a pitch far beyond mere ability."

Queen Elizabeth trusted Cecil to give him good advice. They both saw the nation's future as bound up with the Protestant Reformation. She told Cecil and her Privy Council: "I give you this charge that you shall be of my Privy Council and content to take pains for me and my realm. This judgement I have of you that you will not be corrupted by any manner of gift and that you will be faithful to the state; and that without respect of my private will, you will give me that counsel which you think best and if you shall know anything necessary to me of secrecy, you shall show it to myself only. And assure yourself I will not fail to keep taciturnity therein and therefore herewith I charge you."

According to his biographer, Wallace T. MacCaffrey: "Cecil made immediate use of the powers inherent in it and quickly took the lead in conducting all public business. This office, through which all official correspondence flowed - outgoing and incoming, foreign and domestic - offered an ambitious man the opportunity to become the centre to which all public business gravitated. Nothing would be done in which his voice had not been heard."

Cecil advised Queen Elizabeth to be cautious in both religious policy and foreign affairs. He warned her against going to war. It was, he argued, to accept the loss of Calais in order to obtain peace with France. Cecil pointed out that wars were expensive and that the "treasury was bare". One of Cecil's common sayings was that the "realm gains more from one year of peace than from ten years of war". While he refrained from changing his opinion if it differed from Elizabeth's, Cecil followed her will once she had made a decision.

It is claimed that this relationship sometimes resulted in a failure to make decisions: "On those occasions when her instincts and Cecil's did not immediately converge, the result was hesitation. Throughout her reign, hesitancy and parsimony were continually picked out by her councillors, in their private correspondence and comments, as her besetting political failings (though both traits may well have saved her from numerous expensive mistakes!). " (31) William Camden said: "Of all men of genius he was the most a drudge; of all men of business, the most a genius."

Mathew Lyons has pointed out that Cecil's closeness to Queen Elizabeth resulted in hostility of the nobility. "The group's Catholicism distracts from the more general reactionary nostalgia of its worldview... It was fed by resentment of the rising gentry families, of which Cecil was the most egregious and of course most powerful example; by a sense of sour entitlement, the humiliation of proud men excluded from positions of influence that their ancestors had held."

In the opinion of many Catholics, Elizabeth was illegitimate, and Mary Stuart, as the senior descendant of Henry VIII's elder sister, was the rightful queen of England. Henri II of France proclaimed his eldest son, François, and his daughter-in-law king and queen of England, and in France the royal arms of England were quartered with those of Francis and Mary.

On 10th July 1559, King Henri was killed by Gabriel Montgomery during a tournament. Mary's fifteen year old husband became king of France. This development caused concern in England and urged on by William Cecil, Queen Elizabeth ordered an English fleet to cut the sea link between Scotland and France.

Cecil now urged the Queen to form an alliance with Scotland that would provide a more secure barrier against France. It would also serve as a united front against any Catholic crusade against Protestantism. The Queen had doubts about this policy and "it required weeks of carefully managed manipulation and Cecil's threat of resignation to win her consent, first to a subsidy to the Scots lords, then a blockade, and finally an expeditionary force to assail the French entrenched in Leith".

In the early months of 1560, negotiations between the countries took place. Under the terms of the Treaty of Edinburgh, signed in July, both France and England agreed to withdraw their forces from Scotland and leave the religious question to be settled by the Scottish Parliament. The body met in August and imposed the Reformation upon Scotland and the celebration of mass was forbidden.

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester soon emerged as one of Elizabeth's leading advisers and was given the post of Master of the Horse. This made him the only man in England officially allowed to touch the Queen, as he was responsible for helping Elizabeth mount and dismount when she went horse-riding. He was described as "splendid in appearance and a promptness and energy of devotion". He was allotted official quarters in the palace. He encouraged her to go riding every day. Unlike most of her officials, Dudley was of her own age. "Although Elizabeth did have some women friends, she much preferred the company of men, and it soon became apparent that she preferred Robert Dudley's company to any other."

According to Leicester's biographer, Simon Adams: Robert Dudley's peculiar relationship to Elizabeth began to attract comment. This relationship - which defined the rest of his life - was characterized by her almost total emotional dependence on him and her insistence on his constant presence at court.... It also helps to explain his separation from his wife." Elizabeth gave Leicester land in Yorkshire, as well as the manor of Kew. She also gave him a licence to export woolen cloth free of charge. It is estimated that this was worth £6,000 in 1560.

During the summer of 1560 Queen Elizabeth and Leicester spent every day together. The story that the couple were lovers and that Elizabeth was pregnant had spread across the country. In June, a sixty-eight-year-old widow from Essex, "Mother Dowe", was arrested for "openly asserting that the Queen was pregnant by Robert Dudley". John de Vere, the 16th Earl of Oxford, wrote to Cecil with news that Thomas Holland, vicar of Little Burstead, had been detained for telling another man that the Queen "was with child". Oxford wanted to know whether he should follow the usual punishment for "rumour-mongers" and cut off Holland's ears.

William Cecil became even more concerned after the death of Leicester's wife, Amy Dudley. Cecil feared that Elizabeth would marry Leicester. The Queen insisted that this would never happen and to show how much she valued Cecil she bestowed on him the lucrative office of Master of the Wards. The two men agreed to work together: "Relations between the men were flexible, adapted to circumstance, sometimes in opposition on a given question, often collaborating to attain a commonly agreed purpose. The basic difference between the two was one of personal goals. Cecil, although of course seeking personal gain and social advancement, pursued power for the promotion of public ends. Leicester, once his marital hopes faded, turned to the traditional ambitions of a nobleman: military fame, the glories of successful command in the field."

In 1562 Queen Elizabeth nearly died of smallpox. William Cecil now focused his attention on the awkward problem of her marriage and the succession. The death of the queen without a settled succession would imperil everything for which he had worked. In 1563 Cecil gave his support to a parliamentary petition to Queen Elizabeth that she marry. She met a parliamentary delegation in the Great Gallery at Whitehall Palace. When they begged her to marry she replied that she would act as God directed her. If God directed her not to marry she would obey. She withdrew her Coronation ring, and holding it up to them, she said: "I am already bound unto a husband, which is the Kingdom of England."

In 1566 members of Parliament tried to force the Queen into action by discussing the subject in the House of Lords and the House of Commons. Elizabeth was furious with Parliament for doing this. She made a speech where she pointed out whether she got married or not was something that she would decide. She added that for Parliament to decide this question was like "the feet directing the head".

Cecil favoured the Queen marrying a Protestant foreign prince. However, as Hugh Arnold-Forster has pointed out, the selection of a husband was bound to cause serious political problems: "Who was the queen's husband to be, and what power was he to have over the government of the country? ... If he were a foreigner there was no knowing what power he might get over the queen, power which he would very likely use for the good of a foreign country, and not for the good of England. On the other hand, if he were an Englishman, he must be chosen from among the queen's subjects, and then it was certain that there would be jealousy and strife among all the great nobles in the country when they saw one of their number picked out and made king over them."

Queen Elizabeth often gave William Cecil the impression that she was seriously considering marriage. However, some historians have questioned whether she was only playing politics. To marry and establish the succession would take away at once her immense importance as a matrimonial catch for the heads of the royal families in Europe. She was aware that such a marriage would help build a strong alliance it would also deprive her of an invaluable diplomatic weapon.

In April 1561, Queen Elizabeth told William Maitland: "As long as I live, I shall be Queen of England. When I am dead they shall succeed me who have the most right... I know the English people, how they always dislike the present government and have their eyes fixed upon that person who is next to succeed." Three years later Sir James Melville suggested to the Queen: "You will never marry.... the Queen of England is too proud to suffer a commander... you think if you were married, you would only be Queen of England, and now you are king and queen both."

Some historians have speculated that her doctors had warned her that her body might not be able to withstand the strain of childbirth. Apparently, her personal physician, Dr Robert Huyck, commented that "she was physically incapable of sexual relations. On the other hand, at much the same time a committee of physicians judged her fit to bear children.

During this period Philip II identified William Cecil as his main enemy in court. He wrote to his ambassador in England, Ruy Gómez de Silva: "I avail myself of the occasion, to tell you my opinion of that Cecil. I am in the highest degree dissatisfied with him. He is a confirmed heretic and if with Lord Robert's assistance you can so inflame matters as to crush him down and deprive him of all further share in the administration, I shall be delighted to have it done."

De Silva replied that he considered Cecil to be a good man: "He (Cecil) is... lucid, modest and just, and although he is zealous in serving his queen, which is one of his best traits, yet he is amenable to reason. He knows the French, and like an Englishman he is their enemy... With regard to his religion I say nothing except that I wish he were a Catholic."

William Cecil was concerned that Queen Elizabeth might be overthrown. He therefore provided money to Francis Walsingham to set-up Britain's first counter-intelligence network. Walsingham was given responsible for the security of the monarch. To protect Elizabeth he created a network of spies in Europe. He received regular reports from twelve locations in France, nine in Germany, four in Italy, four in Spain, and three others in Europe. He also had informants in Constantinople, Algiers and Tripoli. Walsingham was supplied by regular information by his spies in Europe. It was claimed that his spying system was so efficient that secret messages sent from Rome was known in London before it reached Spain.

Walsingham became suspicious of Roberto di Ridolfi, an Italian banker living in London. In October 1569 he brought him in for questioning. He also carried out a search of his house but nothing incriminating was found and he was released in January 1570. Ridolfi's biographer, L. E. Hunt, has suggested he may have become a double-agent during this period: "The leniency of his treatment at the hands of Elizabeth and her ministers has caused some scholars to suggest that during his house arrest Ridolfi was successfully ‘turned’ by Walsingham into a double agent who subsequently worked for, and not against, the Elizabethan government."

Ridolfi now attempted to develop a close relationship with John Leslie, Bishop of Ross and Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, a cousin to the queen and the highest ranking peer in England. Mary Queen of Scots encouraged Norfolk to join the plot by writing to him on 31st January 1571 suggesting marriage. Robert Hutchinson, the author of Elizabeth's Spy Master (2006) has commented: "One can imagine Norfolk's incredulous expression when he read her wholly unrealistic letter, its contents, if not the stuff of daydreams, certainly of rampant self-deception."

According to Norfolk's biographer, Michael A. Graves: "An extensive, overmanned, and vulnerable conspiratorial network, including the servants of the principal participants, planned the release of the Scottish queen, her marriage to the duke, and, with Spanish military assistance, Elizabeth's removal in favour of Mary and the restoration of Catholicism in England. The success of the plan required Norfolk's approval and involvement. An initial approach by the bishop of Ross, forwarding ciphered letters from Mary, failed to secure his support. However, Norfolk reluctantly agreed to meet Ridolfi, as a result of which he gave verbal approval to the request for Spanish military assistance."

Roberto di Ridolfi eventually convinced Howard to sign a declaration stating that he was a Catholic and, if backed by Spanish forces, was willing to lead a revolt. "The plan, later to be known as the Ridolfi plot, was soon in place: a Catholic rising was to free Mary and then, with zealous Catholics as well as Spanish forces joining en route, bring her to London, where the queen of Scots would supplant Elizabeth. The English queen's ultimate fate was purposely left unclear for the benefit of those with tender consciences. Mary would then secure her throne by marrying Norfolk."

Ridolfi received through Ross a paper of detailed instructions agreed on by Norfolk and Mary Queen of Scots. This empowered him to ask the Duke of Alva for guns, ammunition, armour and money, and 10,000 men, of whom 4,000, it was suggested, might make a diversion in Ireland. Ridolfi went to Brussels, where he discussed the plan with Alva. He then wrote to Philip II warning against a serious war against England: "But if the Queen of England should die, either a natural or any other death" then he should consider sending troops to put Mary on the vacant throne. The Ridolfi Plot was ill conceived in the extreme and has been called "one of the more brainless conspiracies" of the sixteenth century

It would seem that Francis Walsingham and William Cecil became aware of the Ridolfi Plot and they "grasped the opportunity to remove Norfolk, once and forever, from the political scene". A servant of Mary Stuart and the bishop of Ross named Charles Bailly had been arrested upon his arrival at Dover on 12th April, 1571. A search of his baggage revealed that Bailly was carrying banned books as well as ciphered correspondence about the plot between Thomas Howard and his brother-in-law John Lumley. Bailly was taken to the Tower and tortured on the rack, and the information obtained from him led to the arrest of the Bishop of Ross and the Duke of Norfolk.

Francis Walsingham also arrested two of of Norfolk's secretaries, who were carrying £600 in gold to Mary's Scottish supporters. (62) At the sight of the rack Robert Higford told all he knew. The second secretary, William Barker, refused to confess and he was tortured. While on the rack his resolution failed and he revealed that secret documents were hidden in the tiles of the roof of one of the houses owned by Norfolk. In the hiding-place Walsingham found a complete collection of the papers connected with Ridolfi's mission, and nineteen letters to Norfolk from the Queen of Scots and the Bishop of Ross.

On 7th September, 1571, Thomas Howard was taken to the Tower of London. He eventually admitted a degree of involvement in the transmission of money and correspondence to Mary's Scottish supporters. He was brought to trial in Westminster Hall on 16th January 1572. His request for legal counsel was disallowed on the grounds that it was not permissible in cases of high treason. The charge was that he practised to deprive the queen of her crown and life and thereby "to alter the whole state of government of this realm"; that he had succoured the English rebels who fled after the failed northern rising of 1569; and that he had given assistance to the queen's Scottish enemies.

It has been claimed that a "state trial of the sixteenth century was little more than a public justification of a verdict that had already been reached". The government case was supported with documentary proof, the written confessions of the bishop of Ross, his servant Bailly, the duke's secretaries, and other servants, and his own admissions. It is claimed that "Norfolk assumed an air of aristocratic disdain in his responses to the mounting evidence against him". This was "reinforced by what appeared to be a disbelief that the greatest noble in the land, scion of an ancient family, could be treated in this way". He was also dismissive of the evidence against him because of the inferiority of those who provided it. At its end he was convicted of high treason, condemned to death, and returned to the Tower to await execution.

Queen Elizabeth was reluctant to authorize the execution of the Duke of Norfolk. Warrants were repeatedly signed and then cancelled. Meanwhile he wrote letters to her, in which he still endeavoured to persuade her of his loyalty, and to his children. He wrote: "Beware of the court, except it be to do your prince service, and that as near as you can in the meanest degree; for place hath no certainty, either a man by following thereof hath too much to worldly pomp, which in the end throws him down headlong, or else he lieth there unsatisfied."

Elizabeth eventually agreed to execute Norfolk but at the last moment she changed her mind. William Cecil complained to Francis Walsingham: "The Queen's Majesty hath always been a merciful lady and by mercy she hath taken more harm than by justice, and yet she thinks she is more beloved in doing herself harm." On 8th February, 1572, Cecil wrote to Walsingham: "I cannot write what is the inward stay of the Duke of Norfolk's death; but suddenly on Sunday late in the night, the Queen's Majesty sent for me and entered into a great misliking that the Duke should die the next day; and she would have a new warrant made that night for the sheriffs to forbear until they should hear further."

On 8th May, 1572, Parliament assembled in an attempt to force Queen Elizabeth to act against those involved in the plot against her. Michael A. Graves points out that Elizabeth finally yielded to pressure, perhaps in the hope that, by "sacrificing Thomas Howard to the wolves, she could spare a fellow queen". Elizabeth refused to take action against Mary Queen of Scots but agreed that Norfolk would be executed on 2nd June, 1572, on Tower Hill.

Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) has argued: "Since she came to the throne, Elizabeth had ordered no execution by beheading. After fourteen years of disuse, the scaffold on Tower Hill was falling to pieces, and it was necessary to put up another. The Duke's letters to his children, his letters to the Queen, his perfect dignity and courage at his death, made his end moving in the extreme, and he could at least be said that no sovereign had ever put a subject to death after more leniency or with greater unwillingness."

On 25th February 1571, Queen Elizabeth was elevated him to the peerage as Baron Burghley. The following year he was appointed as Lord Treasurer and now had direct responsibility for finance. His main work of Secretary of State was largely carried out by his old friend, Sir Francis Walsingham. Burghley's health was poor and suffered frequent bouts of gout. Attendance at council fell from the 97 per cent of the 1560s to 80 per cent or even less in the 1570s.

Burghley and Walsingham worked in the closest co-operation over intelligence matters. William Camden later claimed: "He (Walsingham) was a most subtle searcher of secrets, nothing being contrived anywhere that he knew not by intelligence." Walsingham did not enjoy a good relationship with the Queen and it was usually left to Burghley to persuade her to change policy as a result of any intelligence gathered.

Burghley joined forces with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, to form an alliance with France. After discussions with Charles IX, Queen Elizabeth now aged 37, was offered the 19 year-old, Henry, Duke of Anjou. Elizabeth claimed to be worried about the age difference, to which Leicester replied, "So much the better for you." Elizabeth thought she was too old to have children: "I am an old woman and am ashamed to talk about a husband, were it not for the sake of an heir." However, a committee of physicians and ladies-in-waiting convinced Burghley that there was no reason why Elizabeth should not, even at this age, bear a child.

It has been argued by some historians that Burghley and Leicester only entered negotiations to arouse the concern of Spain, rather than contemplate marriage seriously. Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012) has suggested that the main reason for these talks was that Charles IX was planning to marry his son to Mary, Queen of Scots, and that Burghley was trying to prevent this union. Catherine de Medici was especially enthusiastic about the marriage: "Such a kingdom for one of my children."

The fact that Elizabeth was a Protestant and Henry was a Catholic, was a difficult problem to overcome. Burghley proposed Anjou be allowed the private use of the mass, provided he conformed to the English service publicly. Charles IX rejected the idea, and the proposed marriage was not helped by Anjou making remarks about the difference of age. When he heard that Elizabeth limped because of a varicose vein, he called her an "old creature with a sore leg".

Aware that the marriage would never take place, Burghley negotiated the Treaty of Blois. Signed on 19th April 1572 England and France relinquished their historic rivalry and established an alliance against Spain. Elizabeth expected the defensive treaty to isolate Spain and prevent France from invading the Low Countries. Burghley also kept open contacts with Spain, looking to improved relations, which he accomplished with the reopening of trade in 1573.

Lord Burghley spent his later years, along with his wife, Mildred Cecil, developing two great country houses, Stamford Baron and Theobalds. Queen Elizabeth was a regular visitor. She treated Burghley very different from the way she dealt with other close advisors such as Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, Christopher Hatton, Walter Raleigh and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. "Burghley's character being such, and so long known to her, Elizabeth never attempted to engage him in her favourite pastime of amourous amusement."

Lord Burghley and Sir Francis Walsingham both advocated an aggressive policy in favour of Protestants in Europe. They became convinced that King Phillip II of Spain, who had been Queen Mary's husband, wanted to make England a Catholic country. He therefore set up a network of spies and agents to prevent this from happening. One of the men who Walsingham was very concerned about was Francis Throckmorton, one of England's most prominent Catholics. In April 1583 Walsingham received a report from Henry Fagot, his agent inside the French embassy, that Throckmorton had dined with the ambassador. A month later Fagot wrote again with the information that "the chief agents for the Queen of Scots are Throckmorton and Lord Henry Howard".

During the early part of the 16th century large numbers of farmers changed from growing crops to raising sheep. This involved enclosing arable land and turning it into pasture for sheep. Sheep farming became so profitable that large landowners began to enclose common land. For hundreds of years this land had been used by all the people who lived in the village. Many people became very angry about this and villagers began tearing down the hedges that had been used to enclose the common land.

In November 1583, Walsingham ordered the arrest of Throckmorton in his London home. He just had time to destroy a letter he was in the act of writing to Mary Stuart, but among his seized papers was a list of the names of "certain Catholic noblemen and gentlemen" and also details of harbours "suitable for landing foreign forces". At first Throckmorton denied they were his, saying they must have been planted by the government searchers. He later admitted that they had been given to him by a man named Nutby who had recently left the country.

Walsingham had Throckmorton put on the rack. During the first two sessions he courageously refused to talk. He managed to smuggle a message out to Bernardino Mendoza, the Spanish ambassador, written in cipher on the back of a playing card, saying he would die a thousand deaths before he betrayed his friends. However, on the third occasion he admitted that Mary Queen of Scots was aware of the plot against Elizabeth. He also confessed that Mendoza was involved in the plot. When he finished his confession he rose from a seat beside the rack and exclaimed: "Now I have betrayed her who was dearest to me in this world." Now, he said, he wanted nothing but death. (82) Throckmorton's confession meant that Walsingham now knew that it was the Spanish rather than the French ambassador who had been abusing his diplomatic privileges.

At his trial Francis Throckmorton attempted to retract his confession claiming that "the rack had forced him to say something to ease the torment". Throckmorton was executed at Tyburn on 10th July 1584 and was reported to have died "very stubbornly", refusing to ask for the Queen Elizabeth's forgiveness. As a result of this case Lord Burghley devised a measure, the bond of association, by which Englishmen individually pledged themselves to kill anyone who claimed the throne on the assassination of the Queen.

In 1591 Robert Persons, a Catholic priest, published Responsio. Published first in Latin, over the next two years it went through eight editions in four languages. It included an attack on Burghley's views on religion. He was described as a "malignant worm" and "ambitious serpent", and accused him not only of atheism but of opening the way to atheist teaching in the universities.

The pamphlet also included an attack on Sir Walter Raleigh. According to Paul Hyland, Raleigh was the leader of "a collection of thinkers, tightly knit or loosely grouped, whose passion was to explore the world and the mind". The group included the geographers, Richard Hakluyt and Robert Hues, the astrologer, Thomas Harriot, the mathematician, Walter Warner, and the writers, Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, George Chapman and Matthew Roydon. The men would either meet at the homes of Raleigh, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, and Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland.

Although the two men shared similar religious views they were bitter political rivals. Lord Burghley became concerned when in 1591 Raleigh succeeded Sir Christopher Hatton as captain of the guard. Burghley told a friend that Raleigh was so close to the Queen that he could do more damage to someone in an hour than he could do good in a year.

Burghley disliked Raleigh and plotted to have him removed from power. It was not long before he discovered that Raleigh had become romantically involved with Elizabeth Throckmorton, her Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber. Elizabeth, who strongly disapproved of her maids-of-honour falling in love. William Stebbing was later to write, in Elizabeth's view "love-making, except to herself, was so criminal at Court that it had to be done by stealth". Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, had both discovered this. It was never any use asking her permission to marry, especially if it were to be to a maid-of-honour, because refusal would be a foregone conclusion. "By and large for Elizabeth the women would be the worst sinners in these clandestine marriages, and usually would be banned from Court forever afterwards."

In July 1591, Bess discovered she was pregnant and begged Raleigh to marry her. He agreed but feared what would happen when Queen Elizabeth discovered the news. They married in secret on 19th November. Meanwhile she remained in the Queen's service, disguising her growing belly as best she could. In the final month of pregnancy, Bess left court and went to live with her brother in Mile End. She had remained at court until the very last moment knowing that if she could be away for less than a fortnight, she would not need a licence to authorise her absence.

On 29th March, 1593, Bess gave birth to a son, Damerei. Soon afterwards she was back in the Queen's service as if nothing had happened. She realised that she was in serious danger as it was strictly forbidden for ladies-in-waiting to marry without the Queen's consent.

Lord Burghley arranged for his twenty-seven-year-old son, Robert Cecil, to carry out an investigation. In an interview with Cecil he denied any romantic relationship with Bess: "I beseech you to suppress what you can any such malicious report. For I protest before God, there is none on the face of the earth that I would be fastened unto."

Burghley took evidence to Queen Elizabeth in May, 1593, that Bess had given birth to Raleigh's child. Both were arrested and on 7th August they were imprisoned in the Tower of London. In an attempt to win back her affection, Raleigh sent the Queen some love poems he had written. He described her as "walking like Venus, the gentle wind blowing her fair hair about her pure cheeks like a nymph." As one historian pointed out: "Elizabeth was irritated rather than pacified by these gestures, smacking as they did of implicit defiance and a wholesale lack of remorse."

Lord Burghley's last years were personally unhappy. His wife and two daughters were both dead. Burghley's health had declined and it seemed he was near death. Queen Elizabeth prayed for him daily and frequently visited him. "When the patient's food was brought and she saw that his gouty hands could not lift the spoon, she fed him.

Philippa Jones, the author of Elizabeth: Virgin Queen (2010) has commented: "By this time, William Cecil was terminally ill. Elizabeth came to the bedside of her 'Spirit' and fed him himself. Although he never played the lover with her, and had never fitted her picture of ideal male beauty, they were closer than most couples. He had always been honest with her and had been her chief adviser since she had assumed the throne - in turn, she had never betrayed him."

William Cecil, Lord Burghley, the only man that Queen Elizabeth probably loved, died at his Westminster house on 4th August 1598. Elizabeth was deeply affected, retiring to her home to weep alone. It is claimed that for the next few months the Privy Council did their best not to mention him at meetings when the Queen was present because it always made her breakdown in tears.

On this day in 1806 politician Charles James Fox died.

Charles James Fox, the son of the Henry Fox, a leading politician in the House of Commons, was born on 24th January, 1749. After being educated at Eton and Oxford University, Fox was elected to represent Midhurst in the Commons when he was only nineteen.

At the age of twenty-one, Fox was appointed by Frederick North, the prime minister, as the Junior Lord of the Admiralty. In December 1772 Fox became Lord of the Treasury but was dismissed by in February 1774 after criticising the influential artist and journalist, Henry Woodfall.

Out of office, Charles Fox opposed North's policy towards America. He denounced the taxation of the Americans without their consent. When war broke out Fox called for a negotiated peace.

In April 1780 John Cartwright helped establish the Society for Constitutional Information. Other members included John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Gales and William Smith. It was an organisation of social reformers, many of whom were drawn from the rational dissenting community, dedicated to publishing political tracts aimed at educating fellow citizens on their lost ancient liberties. It promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform.

Charles Fox became convinced by Cartwright's arguments. He advocated the disfranchisement of rotten and pocket boroughs and the redistribution of these seats to the fast growing industrial towns. When Lord Frederick North's government fell in March 1782, Fox became Foreign Secretary in Rockingham's Whig government. Fox left the government in July 1782, on the death of the Marquis of Rockingham as he was unwilling to serve under the new prime minister, Lord Sherburne. Sherburne appointed the twenty-three year old William Pitt as his Chanchellor of the Exchequer. Pitt had been a close political friend of Fox and after this the two men became bitter enemies.

In 1787 Thomas Clarkson, William Dillwyn and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as Charles Fox, John Wesley, Josiah Wedgwood, James Ramsay, and William Smith gave their support to the campaign. Clarkson was appointed secretary, Sharp as chairman and Hoare as treasurer.

Clarkson approached another sympathiser, Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it." Wilberforce's nephew, George Stephen, was surprised by this choice as he considered him a lazy man: "He worked out nothing for himself; he was destitute of system, and desultory in his habits; he depended on others for information, and he required an intellectual walking stick."

Fox was unsure of Wilberforce's commitment to the anti-slavery campaign. He wrote to Thomas Walker: "There are many reasons why I am glad (Wilberforce) has undertaken it rather than I, and I think as you do, that I can be very useful in preventing him from betraying the cause, if he should be so inclined, which I own I suspect. Nothing, I think but such a disposition, or a want of judgment scarcely credible, could induce him to throw cold water upon petitions. It is from them and other demonstrations of the opinion without doors that I look for success."

In May 1788, Fox precipitated the first parliamentary debate on the issue. He denounced the "disgraceful traffic" which ought not to be regulated but destroyed. He was supported by Edmund Burke who warned MPs not to let committees of the privy council do their work for them. William Dolben described shipboard horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stowed like "herrings in a barrel" and stricken with "putrid and fatal disorders" which infected crews as well. With the support of William Pitt, Samuel Whitbread, William Wilberforce, Charles Middleton and William Smith, Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. The bill passed 56 to 5 and received royal assent on 11th July.

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789 Charles Fox was initially enthusiastic describing it as the "greatest event that has happened in the history of the world". He expected the creation of a liberal, constitutional monarchy and was horrified when King Louis XVI was executed. When war broke out between Britain and France in February 1793, Fox criticised the government and called for a negotiated end to the dispute. Although Fox's views were supported by the Radicals, many people regarded him as defeatist and unpatriotic.

In April 1792, Charles Grey joined with a group of Whigs who supported parliamentary reform to form the Friends of the People. Three peers (Lord Porchester, Lord Lauderdale and Lord Buchan) and twenty-eight Whig MPs joined the group. Other leading members included Richard Sheridan, John Cartwright, John Russell, George Tierney, Thomas Erskine and Samuel Whitbread. The main objective of the the society was to obtain "a more equal representation of the people in Parliament" and "to secure to the people a more frequent exercise of their right of electing their representatives". Charles Fox was opposed to the formation of this group as he feared it would lead to a split in the Whig Party. However, by November eighty-seven branches of the Society of Friends had been established in Britain.

Charles James Fox disapproved of the ideas of Tom Paine and criticised Rights of Man, however, he consistently opposed measures that attempted to curtail traditional freedoms. He attacked plans to suspend habeas corpus in May 1794 and denounced the trials of Thomas Muir, Thomas Hardy, John Thelwall and John Horne Tooke. Fox also promoted Catholic Emancipation and opposed the slave trade. Fox continued to support parliamentary reform but he rejected the idea of universal suffrage and instead argued for the vote to be given to all male householders.

When Lord Grenville became prime minister in 1806 he appointed Charles Fox as his Foreign Secretary. Fox began negotiating with the French but was unable to bring an end to the war. After making a passionate speech in favour of the Abolition of the Slave Trade bill in the House of Commons on 10th June 1806, Fox was taken ill. His health deteriorated rapidly and he died three months later on 13th September, 1806.

On this day in 1831 Thomas Macaulay warns what will happen in the Reform Act is not passed.

"Three weeks will probably settle the whole matter, and bring to the issue the question, Reform or Revolution. One or the other I am certain that we must and shall have. I assure you that the violence of the people, the bigotry of the Lords, and the stupidity and weakness of the ministers, alarm me so much that even my rest is disturbed by vexation and uneasy forebodings."

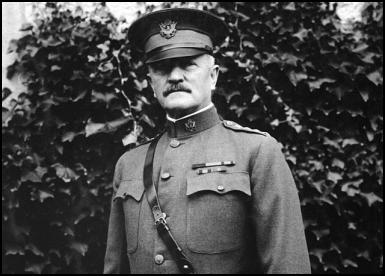

On this day in 1860 John J. Pershing was born on 13th September, in Linn County, Missouri in 1860. After a period as a schoolteacher he went to West Point Military Academy where he eventually became one of its military instructors. Later he held a similar post at Nebraska University.

Pershing served on frontier duty against the Sioux and Apache (1886-1898) and in the Cuban War (1898). Pershing gained further military experience in the Philippines (1903) and with the Japanese Army during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05). This was followed by the military campaign against Pancho Villa in Mexico in 1917.

In 1917 Pershing was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe. His belief that his fit, fresh troops could break the deadlock on the Western Front had to be revised in the first-half of 1918. However, he won praise for his excellent victory at St Mihiel in September, 1918.

Pershing argued for a complete military victory and punitive cease-fire terms. After the war Pershing was highly critical of the Treaty of Versailles. In 1921 Pershing became Chief of Staff of the US Army and later wrote My Experience of War (1931).

John Joseph Pershing died on 15th July 1948.

On this day in 1865 William Birdwood was born in Bombay. Educated at Sandhurst he was commissioned in 1885 and from 1887 served in the India Army.

At the beginning of the First World War Birdwood was put in command of the Australian and New Zealand contingents that took part in the Dardanelles offensive and was responsible for the Gallipoli landings.

After it was decided to withdraw from the area, Birdwood took his troops to the Western Front where took part in the major battles at the Somme and Ypres. In May 1918 Birdwood was replaced by General John Monash as commander of the Australian Imperial Force.

After the First World War Birdwood returned to India to command the Northern Army. He became Commander-in-Chief in 1925 and retired in 1930.

Sir William Birdwood died on 17th May 1951.

On this day in 1879 suffragette Annie Kenney, the daughter of Nelson Horatio Kenney and Anne Wood, was born at Springhead, a suburban area of Saddleworth. Annie's mother had eleven children and worked with her husband in the Oldham textile industry. Annie was born prematurely and was not expected to survive. When Annie reached the age of ten she began work in a local cotton mill. Soon afterwards a whirling bobbin tore off one of her fingers.

At the age of thirteen Kenney became a full-time worker at the mill and had to get up at five in the morning to start at six, and finished work at 5.30 p.m. On arriving home she was expected to help with washing, cooking and scrubbing floors. If she had any free time she played with her dolls.

Annie later recalled that her "father never seemed to have any confidence in his children, he had very little in himself". Although Annie received very little education but her mother encouraged her to read and as a teenager she developed a strong interest in literature. She later recalled: "Mother allowed us great freedom of expression on all subjects.... I grew up with a smattering of knowledge on many questions." Annie was especially impressed by authors such as Tom Paine, Robert Blatchford,Edward Carpenter and Walt Whitman. After being inspired by an article she read in Robert Blatchford's radical journal, The Clarion, Annie joined the local branch of the Independent Labour Party.

At an Independent Labour Party meeting in 1905, Annie Kenney and her sister, Jessie Kenney, heard Christabel Pankhurst speak on the subject of women's rights. Annie was extremely impressed with the content of the speech and the two women soon became close friends. Annie decided to join the recently formed Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Emmeline Pankhurst commented: "There was something about Annie that touched my heart. She was very simple and seemed to have a whole-hearted faith in the goodness of everybody that she met." Christabel Pankhurst added: "She was eager and impulsive in manner, with a thin, haggard face, and restless knotted hands, from one of which a finger had been torn by the machinery it was her work to attend. Her abundant, loosely dressed golden hair was the most youthful looking thing about her... The wild, distraught expression, apt to occasion solicitude, was found on better acquaintance to be less common than a bubbling merriment, in which the crow's feet wrinkled quaintly about a pair of twinkling, bright blue eyes."

The WSPU was often accused of being an organisation that existed to serve the middle and upper classes. As Annie Kenney was one of the organizations few working class members, when the WSPU decided to open a branch in the East End, she was asked to leave the mill and become a full-time worker for the organisation. Annie joined Sylvia Pankhurst in London and they gradually began to persuade working-class women to join the WSPU.

Jessie Kenney also moved to the capital and become the private secretary to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "By the time she was 21 she was the Women's Social and Political Union's youngest organizer, working from Clement's Inn, arranging meetings, publicity stunts, interruptions of cabinet ministers' meetings and, as time passed, acts of militancy." She had different skills from her sister. Sylvia Pankhurst pointed out that Jessie was "eager in manner as her sister Annie, with more system and less pathos, and without any gift of platform speech."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence argued that Annie was a devoted follower of Christabel Pankhurst. "Annie's... devotion took the form of unquestioning faith and absolute obedience ... Just as no ordinary Christian can find that perfect freedom in complete surrender, so no ordinary individual could have given what Annie gave - the surrender of her whole personality to Christabel." Annie admitted that: "For the first few years the militant movement was more like a religious revival than a political movement. It stirred the emotions, it aroused passions, it awakened the human chord which responds to the battle-call of freedom ... the one thing demanded was loyalty to policy and unselfish devotion to the cause."

On 13th October 1905, Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting, the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle, a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were arrested and charged with assault.

Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant (1924) she described what it was like to be in prison with Christabel: "Being my first visit to jail, the newness of the life numbed me. I do remember the plank bed, the skilly, the prison clothes. I also remember going to church and sitting next to Christabel, who looked very coy and pretty in her prison cap ... I scarcely ate anything all the time I was in prison, and Christabel told me later that she was glad when she saw the back of me, it worried her to see me looking pale and vacant.

On her release from prison Emmeline Pankhurst sent her to meet the journalist, William Stead. According to Fran Abrams: "Perhaps Emmeline knew of Stead's fondness for young girls, which Sylvia experienced too. On one occasion Annie had to appeal to Emmeline to ask him not to kiss her when she went to his office. But Annie liked Stead, and he quickly became a father figure. Before their first meeting was over she was sitting on the arm of his chair, telling him all about her life. He responded by telling her she must come to him if she was ever lonely or in trouble. Later he even let her use a room in his house in Smith Square to rest during Westminster lobbies and demonstrations, and he lent her £25 to help her organise her first big London meeting." Annie became very close to Stead and used to spend time with him at his house on Hayling Island in Hampshire. In one article Stead argued that Annie Kenney was the new Josephine Butler.

In May 1906 Annie, dressed as the sterotypical mill girl in clogs and shawl, she led a group of women to the home of Herbert Asquith, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. After ringing the bell incessantly, she was arrested and sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. On her release she went on holiday with Christabel Pankhurst and Mary Gawthorpe.

In 1907 Annie Kenney was appointed WSPU organiser at a salary of £2 a week, in the West of England. She was based in Bristol. It was not long before she recruited Victoria Lidiard, a photographer assistant, who became one of her assistants. The following year she met Mary Blathwayt at a WSPU meeting in Bath. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), claims that Blathwayt had fallen "under her spell and gave her a rose". Over the next few years she was to spend a lot of time at Blathwayt's home at Eagle House near Batheaston "where, for the first time, she began to learn French, to play tennis, to swim, to ride and to drive."

Annie Kenney was to go to prison several times during the next six years. William Stead compared her to Joan of Arc, whereas Josephine Butler described her as: "A woman of refinement and of delicacy of manner and of speech. Her physique is slender, and she is intensively nervous and high strung. She vibrates like a harpstring to every story of oppression."

In March 1910, Annie and Christabel Pankhurst went on holiday together in Guernsey. A fellow member of the WSPU, Teresa Billington-Greig claimed that Annie was "emotionally possessed by Christabel". However, Mary Blathwayt, who spent a lot of time with Annie during this period argued that it was Annie who was the dominating personality as she had a "wonderful influence over people".

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that Annie Kenney had a series of romantic attachments with other suffragettes: "The relationship (with Christabel Pankhurst) would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments. One historian who argues that Annie must have had sexual feelings for other women adds that lesbianism was barely recognised at the time. Such relationships, even when they involved sharing beds, excited little comment. Already, Christabel had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family - according to Sylvia."

Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote on 7th September 1910 that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account. The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else."

Teresa Billington-Greig has argued that Annie was also very close to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. "It is true that there was an immediate and strong emotional attraction between Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Annie Kenney... indeed so emotional and so openly paraded that it frightened me. I saw it as something unbalanced and primitive and possibly dangerous to the movement ... but the emotional obsession died out and the partnership... persisted for many years."

Annie admitted in her autobiography that suffragettes developed a different set of values to other women at the time: "The changed life into which most of us entered was a revolution in itself. No home life, no one to say what we should do or what we should not do, no family ties, we were free and alone in a great brilliant city, scores of young women scarcely out of their teens met together in a revolutionary movement, outlaws or breakers of laws, independent of everything and everybody, fearless and self-confident."

When Christabel Pankhurst fled to France to avoid arrest in 1912, Annie was put in charge of the WSPU in London. She appointed Rachel Barrett as her assistant. Every week Annie travelled to Paris to receive Christabel's latest orders. Fran Abrams has pointed out: "It was the start of a cloak-and-dagger existence that lasted for more than two years. Each Friday, heavily disguised, Annie would take the boat-train via La Havre. Sundays were devoted to work but on Saturdays the two would walk along the Seine or visit the Bois de Boulogne. Annie took instructions from Christabel on every little point - which organiser should be placed where, circular letters, fund-raising, lobbying MPs... During the week Annie worked all day at the union's Clement's Inn headquarters, then met militants at her flat at midnight to discuss illegal actions. Christabel had ordered an escalation of militancy, including the burning of empty houses, and it fell to Annie to organise these raids. She did not enjoy this work, nor did she agree with it. She did it because Christabel asked her to, she said later."

In 1912 the WSPU began a campaign to destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. By December, the government claimed that over 5,000 letters had been damaged by the WSPU. The WSPU also began a new arson campaign. Under the orders of Christabel Pankhurst, attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote.

The militant campaign was directed from Annie's flat that she shared with Jessie Kenney and another one of her lovers, Rachel Barrett. She asked Elizabeth Robins to witness a letter that Christabel Pankhurst sent her in which she gave her control of the WSPU in London.

Annie Kenney was charged with "incitement to riot" in April 1913. She was found guilty at the Old Bailey and was sentenced to eighteen months in Maidstone Prison. She decided that Grace Roe should now became head of operations in London. She immediately went on hunger strike and became the first suffragette to be released under the provisions of the Cat and Mouse Act. Kenney went into hiding until she was caught once again and returned to prison. That summer she escaped to France during a respite and went to live with Christabel Pankhurst in Deauville.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 ended the WSPU militant campaign for the vote. Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

Fran Abrams, the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued: "Annie, now becoming increasingly uncomfortable with Christabel's autocratic style, must have shown some hint of her true feelings because she was soon asked to leave the country. One of the leaders of the movement should be safe in case of invasion, Christabel said."

Annie Kenney was sent to the United States. She did not enjoy the experience and when Christabel Pankhurst arrived in the country to make a speech at Carnegie Hall urging Americans to enter the war on the side of the Allies, Kenney managed to persuade Christabel to allow her to come home.

In 1915 the WSPU sent Annie Kenney to Australia to help the prime minister, William Hughes, in a referendum campaign on conscription. On her return she worked with David Lloyd George to help find female recruits for the munition factories. She was also involved in organizing an Anti-Bolshevist campaign against strikes.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Kenney helped Christabel Pankhurst in her election campaign in Smethwick. Despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, Christabel lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party.

In 1918 Annie Kenney went to live with Grace Roe in St Leonards-on-Sea in Sussex. The two women became followers of Annie Besant, who was the leader of the Theosophy movement in Britain. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), Grace Roe later "remarked on the part played by theosophists behind the scenes of the militant suffrage movement. She made the point that theosophy not only gave a spiritual dimension to their lives but, cutting across class, put people in touch with each other who would have been unlikely otherwise to meet."

While staying with her sister on the Isle of Arran, she met James Taylor (1893-1977). Mary Blathwayt claims in her diary that Taylor "is quite simple like Annie and has a divine singing voice." The couple were married in April 1920 at St Cuthbert's Church. They moved to Letchworth, where Taylor was appointed maintenance engineer at St Christopher's School. A son, Warwick Kenney Taylor, was born in February, 1921. Her sister, Jessie Kenney, worked as a steward on a cruise liner but used Annie's home as a base.

Kenney lost interest in politics but she continued to keep in contact with Christabel Pankhurst. In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant (1924) she wrote: "There is a cord between Christabel and me that nothing can break - the cord of love... We started militancy side by side and we stood together until victory was won."

James Taylor claims that his wife never really recovered from her hunger strikes and, after a long, and steady decline, she died of diabetes at the Lister Hospital in Hitchen on 9th July, 1953.

On this day in 1894 writer John Boynton Priestley, the only child of Jonathan Priestley (1868–1924), and his first wife, Emma Holt (1865–1896), was born in Manningham, a suburb of Bradford on 13th September, 1894. Despite being the son of an illiterate mill worker, his father became a school teacher. His mother died when he was only two years old and in in 1898 his father married Amy Fletcher, whom Priestley described as a loving stepmother.

Priestley was educated at Whetley Lane Primary School, and then, on a scholarship, Belle Vue High School. Bored with school he left education and the age of sixteen and found work as a clerk for a wool firm in Bradford. He joined the Labour Party and began writing a column in their weekly newspaper, The Bradford Pioneer.

On the outbreak of the First World War Priestley immediately joined the British Army. He later recalled: "It is not true, as some critics of the British high command have suggested, that Kitchener's army consisted of brave but half-trained amateurs, so much pitiful cannon-fodder. In the earlier divisions like ours, the troops had months and months of severe intensive training. Our average programme was ten hours a day, and nobody grumbled more than the old regulars who had never been compelled before to do so much and for so long."

Priestley was sent to France and served on the Western Front. He wrote to his father on 27th September, 1915: "In the last four days in the trenches I don't think I'd eight hours sleep altogether. It is frightfully difficult to walk in the trenches owing to the slippery nature of things, the most appalling thing is to see the stretcher bearers trying to get the wounded men up to the Field Dressing station. On Saturday morning we were subjected to a fearful bombardment by the German artillery; they simply rained shells. One shell burst right in our trench - and it was a miracle that so few - only four - were injured. I escaped with a little piece of flesh torn out of my thumb. But poor Murphy got a shrapnel wound in the head - a horrible great hole - and the other two were the same. They were removed soon after and I don't know how they are going on."

Priestley took part in the Battle of Loos and in 1917 he accepted a commission. After being wounded later that year he was sent back to England for six months. Soon after returning to the Western Front he endured a German gas attack. Treated at Rouen he was classified by the Medical Board as unfit for active service and was transferred to the Entertainers Section of the British Army. He wrote over 40 years later: "I felt as indeed I still feel today and must go on feeling until I die, the open wound, never to be healed, of my generation's fate, the best sorted out and then slaughtered, not by hard necessity but by huge, murderous public folly."

When Priestley left the army he became a student at Trinity Hall. While at Cambridge University he gained valuable experience by writing for the Cambridge Review. After completing a degree in Modern History and Political Science, Priestley found work as theatre reviewer with the Daily News. He also contributed articles to the Spectator.

Priestley married Pat Emily Tempest on 29th June 1921. His first book, Brief Diversions (1922) a collection of epigrams, anecdotes, and stories. His second book, Papers from Lilliput, was a series of essays on personalities past and present.He also contributed articles to the Spectator, The Bookman, the Saturday Review, and the Times Literary Supplement.

In March 1923 Priestley's wife gave birth to their first child, Barbara, to be followed prematurely in April 1924 by a second daughter, Sylvia, when it was discovered that Pat was suffering from terminal cancer. Priestley wrote to a friend that he was "so deep in despair I didn't know what to do with myself". However, it was not long long before he was having an affair with Jane Wyndham Lewis, the wife of D. B. Wyndham Lewis, which resulted in the birth of a daughter, Mary, in March 1925. Priestley had a number of affairs and in later life he admitted he "enjoyed the physical relations with the sexes … without the feelings of guilt which seems to disturb some of my distinguished colleagues". Pat Priestley died on 25th November 1925. The following year he married Jane Wyndham Lewis.

Priestley's early critical writings such as The English Comic Characters (1925), The English Novel (1927) and English Humour (1929) established his reputation as an important commentator on literature. With financial support from his friend, Hugh Walpole, Priestley wrote, The Good Companions, a novel 250,000 words long. It was completed in March 1929, and published in July. As his biographer, Judith Cook pointed out: "Sales started slowly, but by Christmas the publishers Heinemann had to use taxis to rush copies to bookshops, so great was the demand; it became one of the best-sellers of the century."

Priestley followed this with what some consider his best novel, Angel Pavement (1930). He also wrote several popular plays such as Dangerous Corner (1932). Priestley also became increasingly concerned about social problems. This is reflected in English Journey (1934), an account of his travels through England. The author of J. B. Priestley (1998) has argued: "He travelled from the south to the north of England, brilliantly describing in bitter prose the poverty and unemployment of the time." Priestley followed this was the plays, Eden End (1934), I Have Been Here Before (1937), Time and the Conways (1937), When we are Married (1938), and Johnson over Jordan (1939).

During the Second World War Priestley became the presenter of Postscripts, a BBC Radio radio programme that followed the nine o'clock news on Sunday evenings. Starting on 5th June 1940, Priestley built up such a following that after a few months it was estimated that around 40 per cent of the adult population in Britain was listening to the programme.

On 21st July, 1940, he argued: "We cannot go forward and build up this new world order, and this is our war aim, unless we begin to think differently one must stop thinking in terms of property and power and begin thinking in terms of community and creation. Take the change from property to community. Property is the old-fashioned way of thinking of a country as a thing, and a collection of things in that thing, all owned by certain people and constituting property; instead of thinking of a country as the home of a living society with the community itself as the first test."

Graham Greene pointed out: "Priestley became in the months after Dunkirk a leader second only in importance to Mr Churchill. And he gave us what our other leaders have always failed to give us - an ideology." Some members of the Conservative Party complained about Priestley expressing left-wing views on his radio programme. Margaret Thatcher has argued that "J.B. Priestley gave a comfortable yet idealistic gloss to social progress in a left-wing direction." As a result Priestley made his last talk on 20th October 1940. These were later published in book form as Britain Speaks (1940).