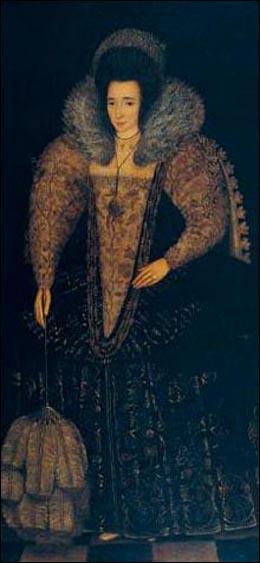

Elizabeth (Bess) Raleigh

Elizabeth (Bess) Throckmorton, the daughter of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton and his wife, Anne Carew Throckmorton, was born on 16th April 1565. Her father was a member of the household of Catherine Parr, and like her was a Protestant and knew Anne Askew. He also served Edward VI and Queen Elizabeth and served as a diplomat from May 1559. (1)

In 1584 her brother, Arthur Throckmorton, negotiated a place for Bess for her in the royal household as a maid in the royal household. (2) According to Paul Hyland, Elizabeth (Bess) was "a tall, unusual beauty with her long face, luminous eyes, strong nose and provocatively modest lips." (3)

Bess held the post of "Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber in 1584. As another historian has pointed out: "Aged nineteen, this was a prestigious position for one so young. She was attractive, passionate, strong-minded and determined." (4) However, Robert Lacey disagrees and claims that she was the "most ugly of Elizabeth's maids of honour." (5)

Marriage to Walter Raleigh

By 1590 Bess was romantically involved with Walter Raleigh, who had a close relationship with Queen Elizabeth, who strongly disapproved of her maids-of-honour falling in love. William Stebbing was later to write, in Elizabeth's view "love-making, except to herself, was so criminal at Court that it had to be done by stealth". Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, had both discovered this. It was never any use asking her permission to marry, especially if it were to be to a maid-of-honour, because refusal would be a foregone conclusion. "By and large for Elizabeth the women would be the worst sinners in these clandestine marriages, and usually would be banned from Court forever afterwards." (6)

Raleigh had been a member of the royal court since 1580. In May 1583 Raleigh received a patent for the sale of wine and the licensing of vintners, worth at a minimum over £700 per annum, and this remained the foundation-stone of his fortunes. The following year the traveller Leopold von Wedel, recounting a visit to the English court, offered further insight into the relationship. Chatting with her courtiers, Queen Elizabeth pointed "with her finger at his face, that there was smut (dirt) on it, and was going to wipe it off with her handkerchief; but before she could he wiped it off himself". Von Wedel commented that his reaction suggested that Raleigh enjoyed an intimate relationship with the Queen. (7)

Anna Whitelock, the author of Elizabeth's Bedfellows: An Intimate History of the Queen's Court (2013) has pointed out: "Raleigh, then around thirty years of age... was strikingly attractive, six foot tall with a trimmed beard and piercing blue eyes and a love of extravagant clothes, jewels and pearls. His boldness, blatant ambition, vanity, and self-confidence all greatly appealed to the Queen... In 1583, Elizabeth granted him one of her favourite palaces, the handsome London dwelling Durham Place on the Strand.. Raleigh wooed her with poetry and they spent increasing amounts of time together, talking, playing cards and riding out. He was frequently in the Privy Chamber by day and night, and would often be at the door of the bedchamber, waiting for Elizabeth to emerge in the morning." (8)

In July 1591, Bess discovered she was pregnant and begged Raleigh to marry her. He agreed but feared what would happen when Queen Elizabeth discovered the news. (9) They married in secret on 19th November. Meanwhile she remained in the Queen's service, disguising her growing belly as best she could. In the final month of pregnancy, Bess left court and went to live with her brother in Mile End. She had remained at court until the very last moment knowing that if she could be away for less than a fortnight, she would not need a licence to authorise her absence. (10)

On 29th March, 1593, Bess gave birth to a son, Damerei. Soon afterwards she was back in the Queen's service as if nothing had happened. She realised that she was in serious danger as it was strictly forbidden for ladies-in-waiting to marry without the Queen's consent. (11)

Rumours soon began to circulate about Bess's relationship with Raleigh. Robert Cecil, the twenty-seven-year-old son of William Cecil, decided to investigate. In an interview with Cecil he denied any romantic relationship with Bess: "I beseech you to suppress what you can any such malicious report. For I protest before God, there is none on the face of the earth that I would be fastened unto." (12)

Imprisonment of Lady Elizabeth Raleigh

Cecil took evidence to Queen Elizabeth in May, 1593, that Bess had given birth to Raleigh's child. Both were arrested and on 7th August they were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Raleigh was placed in the Brick Tower. Bess was placed elsewhere, and although both were allowed servants and visitors, they were kept apart. (13)

In an attempt to win back her affection, Raleigh sent the Queen some love poems he had written. He described her as "walking like Venus, the gentle wind blowing her fair hair about her pure cheeks like a nymph." (14) As one historian pointed out: "Elizabeth was irritated rather than pacified by these gestures, smacking as they did of implicit defiance and a wholesale lack of remorse." (15)

In September, 1593, some of Raleigh's fleet arrived back in England after capturing the Portuguese ship, Madre de Dios, that was carrying a great deal of treasure that amounted to £34,000. (16) Raleigh was released at the request of Sir John Hawkins and sent to Dartmouth where he was only allowed to keep only £2,000 of the money. On 22nd December, Elizabeth Throckmorton, was also allowed to leave the Tower, only to discover that her son, Damerei, had died of the plague, while she had been imprisoned. (17)

Raleigh gradually rebuilt his relationship with Queen Elizabeth. Mathew Lyons, the author of The Favourite: Raleigh and His Queen (2011) has attempted to explain the reasons for this: "When Raleigh married there would be pain for both of them, but in these years when their relationship was at its zenith, there is a steady and enduring sense of comfort and ease between them, a care that transcended the fraught and difficult use to which they were sometimes compelled to put each other. I think we can call that love." (18)

On 1st November 1593 the couple's second child, Walter was baptized at Lillington, Dorset, near the foundations of a fine new house Walter Raleigh was beginning to build close by the old castle at Sherborne. Raleigh was elected to the House of Commons. Over the next couple of years he warned fellow MPs of the dangers posed by Spain, demanding pre-emptive action and increased spending on the navy. (19)

Walter Raleigh accused of Treason

Queen Elizabeth died on 24th March, 1603. The funeral took place a month later. On Thursday 28th April, a procession of more than a thousand people made its way from Whitehall to Westminster Abbey. "Led by bell-ringers and knight marshals, who cleared the way with their gold staves, the funeral cortege stretched for miles. First came 260 poor women... Then came the lower ranking servants of the royal household and the servants of the nobles and courtiers. Two of the Queen's horses, riderless and covered in black cloth, led the bearers of the hereditary standards... The focal point of the procession was the royal chariot carrying the Queen's hearse, draped in purple velvet and pulled by four horses... On top of the coffin was the life-size effigy of Elizabeth... Sir Walter Raleigh and the Royal Guard walking five abreast, brought up the rear, their halberds held downwards as a sign of sorrow." (20)

Henry Howard, youngest brother of Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, wrote to King James questioning the loyalty of Walter Raleigh. Howard described Raleigh as "an atheist, indiscreet, incompetent, hostile to the very idea of James's succession". It is believed that Howard wrote these letters on behalf of Robert Cecil, who saw Raleigh as a potential rival for the important post of chief government minister. (21)

Walter Raleigh was stripped of his monopolies and captaincy of the guard in May, and was given notice to quit Durham Place, Tobias Matthew, bishop of Durham, having successfully petitioned James for the return of his London home. On 15th July, Raleigh was detained for questioning in connection with a plot to put Arabella Stewart on the throne. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London and on 27th July he tried to stab himself to the heart using a table knife. (22)

Raleigh was tried in November 1603. As a result of an outbreak of plague in London it was decided to hold the trial in the Great Hall of Winchester Castle. (23) According to one source "when Raleigh was escorted from the Tower by a guard of fifty horse, it was touch and go whether he would make it out of the city alive, for the mob was determined to see the disdainful courtier dashed to the ground." (24)

The main evidence against him was the signed confession of Henry Brooke, 11th Baron of Cobham. However, Brooke, withdrew his accusations almost as soon as they were made. Raleigh argued: "Let my accuser come face to face, and be deposed". However, the jury was not told about this and Brooke was not allowed to testify and be cross-examined. (25)

Walter Raleigh was found guilty of treason and sentenced to be hung, drawn and dismembered. However, King James granted him a last-minute reprieve and was ordered to spend the rest of his life confined to the Tower of London. Raleigh was also stripped of all his titles. His letters reveal the depths of his depression and hopelessness during this period. Eventually, he decided to spend his time studying history and science. (26) Elizabeth Raleigh took a house on Tower Hill and was allowed to make regular visits to see her husband. Their third son, Carew Raleigh, was born in February 1605.

Raleigh's Last Journey

During his time in prison Walter Raleigh began to outline plans for proposed voyages to the Americas. It has been pointed out that in a eight year period, over half of his letters dealt with this subject. Raleigh was released on 19th March 1616, and at once set about planning his expedition. The planning was, of course, extensive, and little he said or did comforted those at court who were determined on a lasting peace with Spain. He discussed with Sir Francis Bacon, attorney-general, the possibility of seizing Spanish ships carrying treasure. Bacon warned him against this action as it would be an act of piracy.

Historians have dismissed Raleigh's final voyage to the Orinoco River to try to find El Dorado as the hopeless pursuit of fantasy. However, Raleigh appeared certain that his trip would be a financial success. Raleigh's fleet sailed from Plymouth on 12th June 1617, but storms and adverse winds detained it off the southern coast of Ireland for nearly two months. Never comfortable at sea, Raleigh succumbed to fever, and was unable to face solid food for nearly a month. The fleet did not arrive in harbour, at the mouth of the Cayenne River, until 14th November. An expedition under Lawrence Keymis, with Raleigh's nephew George Raleigh in command of the land forces, sailed up the Orinoco in five ships on 10th December. (27)

Carrying provisions for one month, the three vessels that survived the shoals of the delta battled against strong currents and arrived at the settlement San Thomé on 2nd January 1618. Keymis attacked the Spanish outpost in violation of peace treaties with Spain. In the initial attack on the settlement, Raleigh's son, Walter, was fatally shot. Keymis, who broke to Sir Walter the news of his son's death, begged for forgiveness. "Raleigh, fully aware of the implications of these events, confronted him with the bitter statement that Keymis had ruined him by his actions, and refused to support the latter in his report to the English backers. Keymis left Raleigh's cabin, saying that he knew what action to take, and went back to his ship. Raleigh then heard a pistol shot, and sent his servant to enquire what was happening, to which Keymis, lying on his bed, replied that he was just discharging a previously loaded pistol. Half an hour later Keymis's boy entered the cabin and found him dead. The ball had only grazed a rib, and after Raleigh's servant had left he stabbed himself to the heart with a long knife." (28)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Raleigh planned another expedition to discover the El Dorado. He also considered plundering the Spanish treasure fleet. However, his men refused to follow him and the rest of his fleet sailed north leaving Raleigh in his own ship, The Destiny. With a rebellious crew he sailed towards Newfoundland, then across the Atlantic to Ireland. Several members of his crew deserted and Raleigh, with the remnant of his force, sailed on to Plymouth. On his return he wrote to his wife: ‘My brains are broken and tis a torment to me to write… as Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins died heart-broken when they failed of their enterprise, I could willingly die." (29)

Raleigh was placed under arrest by order of Charles Howard of Effingham soon after his landing and conveyed to London by his cousin Sir Lewis Stucley, vice-admiral of Devon and was imprisoned on his arrival on 10th August. Raleigh and the surviving members of his crew were interrogated. On 18th October the commissioners reported their findings to King James. As the evidence against Raleigh was not strong the King issued a warrant for executing the sentence of 1603. (30)

The night before the planned execution Bess was allowed to visit her husband. She told him that she had been given permission to take possession of his corpse and therefore avoiding the terrible tradition of cutting up his body and having it displayed in the city. Raleigh commented: "It is well, dear Bess, that thou may dispose of it dead that had not always the disposing of it when it was alive." (31)

Walter Raleigh was taken to be executed at Whitehall on 29th October 1618. He wore a crisp white ruff, a tawny coloured doublet, a black embroidered waistcoat under it, taffeta breeches, silk stockings, a black velvet gown and a fine pair of shoes. On his finger he had a ring with a diamond that had been given to him by Queen Elizabeth. (32)

Edward Coke, the attorney-general, made a speech about the justice of the punishment: "Sir Walter Raleigh hath been a statesman, and a man who in regard to his parts and quality is to be pitied. He hath been as a star at which the world hath gazed; but stars may fall, nay they must fall when they trouble the sphere in which they abide... You had an honourable trial, and so were justly convicted... You might think it heavy if this were done in cold blood, to call you to execution; but it is not so, for new offences have stirred up his Majesty's justice, to remember to revive what the law hath formerly cast upon you... I know you have been valiant and wise, and I doubt not but you retain both these virtues, for now you shall have occasion to use them. Your faith hath heretofore been questioned, but I am resolved you are a good Christian, for your book, which is an admirable work, cloth testify as much... Fear not death too much, nor fear death too little.... And here I must conclude with my prayers to God for it, and that he would have mercy on your soul." (33)

Walter Raleigh replied: "My honourable good Lords, and the rest of my good friends that come to see me die... As I said, I thank God heartily that he hath brought me into the light to die, and hath not suffered me to die in the dark prison of the Tower, where I have suffered so much adversity and a long sickness. And I thank God that my fever hath not taken me at this time, as I prayed God it might not. But this I say, for a man to call God to witness to a falsehood at any time is a grievous sin... But to call God to witness to a falsehood at the time of death is far more grievous and impious... I do therefore call God to witness, as I hope to see him in his kingdom, which I hope I shall within this quarter of this hour... I did never entertain any conspiracy, nor ever had any plot or intelligence with the French King, nor ever had any advice or practice with the French agent, neither did I ever see the French hand or seal, as some have reported I had a commission from him at sea." (34)

The executioner attempted to place a blindfold on Raleigh. He refused with the words: "Think you I fear the shadow of the axe, when I fear not the axe itself." Raleigh placed his head on the block. The executioner did not react and Raleigh shouted out: "What dost fear? Strike, man, strike!" The executioner took off his head with two blows of his axe. He lifted up the head and showed it on all sides, but could not bring himself to utter the conventional words: "This is the head of a traitor." (35)

Raleigh's head was placed into a red leather bag. The body was covered by his velvet cloak. Both were carried away in Lady Raleigh's mourning coach. (36) Bess wrote to her brother, Nicholas Throckmorton asking him to bury the body in Beddington: "I desire, good brother, that you will be pleased to let me bury the worthy body of my noble husband, Sir Walter Raleigh, in your church at Beddington, where I desire to be buried. The lords have given me his dead body, though they denied me his life. This night he shall be brought you with two or three of my men. Let me hear presently." (37)

However, Nicholas Throckmorton refused to accept the body and he was buried at St Margarets's Church in London. Lady Raleigh had her husband's head embalmed and preserved in its red bag. It was kept in a cupboard and displayed to visitors who revered his memory until her death twenty-nine years later. (38)

Lady Elizabeth Raleigh died in 1647.

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Hyland, Ralegh's Last Journey (2003)

Towards the end of 1584, when Bess's brother Arthur Throckmorton had negotiated a place for her in the royal household as a maid of the Privy Chamber, there he was. Walter Raleigh, not yet Sir Walter. That year he had sent a reconnoitering expedition to the New World; he gave the territory his scouts discovered the name Virginia, in honour of the Queen who would not permit him to cross the ocean to see it for himself.

Elizabeth Throckmorton was enchanted and flattered by Raleigh. Walter, at thirty-four, was captivated by this Maid of Honour, twelve years his junior. That she shared' the Virgin Queen's name was tantalising. Ralegh's fantasies had been invaded by a fresh Elizabeth, a tall, unusual beauty with her long face, luminous eyes, strong nose and provocatively modest lips.

(2) Anna Whitelock, Elizabeth's Bedfellows: An Intimate History of the Queen's Court (2013)

Bess Throckmorton had entered the Queen's service as a Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber in 1584. Aged nineteen, this was a prestigious position for one so young. She was attractive, passionate, strong-minded and determined. By 1590 she had caught the eye of Sir Walter Ralegh, a dashing courtier and adventurer whose job it was to protect the Queen and her ladies, and before long the two began meeting clandestinely. In July 1591, Bess discovered she was pregnant and begged Ralegh, then in his late thirties, to marry her. He agreed, though he dreaded the Queen's reaction. They married in secret on 19th November. Meanwhile Bess remained in the Queen's service, disguising her growing belly as best she could, and Sir Walter continued with his preparations for his next military expedition to Panama. At the end of February, in her final month of pregnancy, Bess left court and went to her brother's house at Mile End to prepare for the birth. She had remained at court until the very last moment knowing that, if she could be away for less than a fortnight, she would not need a licence to authorise her absence.

After her sudden departure rumours began to circulate about Bess's relationship with Ralegh. Robert Cecil, the twenty-seven-year-old son of' William Cecil, and now a privy councillor, became suspicious and started questioning Ralegh. Sir Walter explicitly denied any relationship with Bess, and swore that there had been no marriage, there would be no marriage and that he was entirely devoted to Queen Elizabeth.... Raleigh was unaware that Robert Cecil had already found out about the marriage and therefore knew that he was being lied to.

(3) Robert Lacey, Robert, Earl of Essex (1971)

Sir Walter Raleigh was unfaithful. Not as Essex had been unfaithful, marrying with youthful enthusiasm a noble, if penniless, widow. But by seducing, at the mature age of forty and in full possession of his senses, the eldest and most ugly of Elizabeth's maids of honour - Bess Throckmorton. To marry, after a dozen years of courtly loyalty, his mistress's attendant seemed a calculated insult. And Elizabeth certainly took it as such. She had the new husband and wife clapped instantly behind bars in the Tower of London - in separate cells. Essex must have breathed deeply to think how close he had been to a similar fate, and to see one rival to his eminence so neatly cast aside.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)