Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury

Robert Cecil, the son of William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley and Mildred Cooke, was born on 1st June, 1563 at Cecil House, Strand, London. At the time his father was Secretary of State and the main advisor to Queen Elizabeth. (1)

Mathew Lyons has pointed out that Cecil's closeness to Queen Elizabeth resulted in hostility of the nobility. "The group's Catholicism distracts from the more general reactionary nostalgia of its worldview... It was fed by resentment of the rising gentry families, of which Cecil was the most egregious and of course most powerful example; by a sense of sour entitlement, the humiliation of proud men excluded from positions of influence that their ancestors had held." (2)

When he was a child Richard Cecil was dropped by his nursemaid and left with permanent curvature of the spine. (3) He was educated at home, first by his mother, one of the most learned women of her generation, then by tutors. He was taught Greek, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish, together with music, mathematics, and cosmography. Cecil was thoroughly grounded in the Bible and the prayer book. His parents took care to converse over meals with Richard and the other children. (4) This included Robert Devereux, the young son of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, who had died in 1576. (5)

Education of Richard Cecil

Anka Muhlstein has argued "The two youngsters, so dissimilar in their tastes and talents, had never been close, but William Cecil's affection for Essex and the later's respect for the old man were never disputed." (6) Robert Lacey, the author of Robert, Earl of Essex (1971) has claimed that Robert's presence caused problems for Richard: "Though Essex was younger than Cecil he must even then have overtopped the stunted cripple - and he far outshone him in beauty. Erect and wiry with a handsome head of curly hair, the nine-year-old Robert Devereux charmed everyone he met." (7)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In 1580 Richard Cecil was admitted to Gray's Inn, and received legal instruction while continuing to live at home. In July 1581 he was at Cambridge University but there is no evidence that he completed an academic year, and he did not take a degree. After further tutoring at home in 1582 by William Wilkinson, fellow of St John's College, Cecil spent the summer and autumn of 1583 in Paris. (8)

House of Commons

In August 1584 Cecil was elected to the House of Commons, for the borough of Westminster; he represented it again in 1586. He was a loyal supporter of Queen Elizabeth and followed closely the policies of William Cecil and Sir Francis Walsingham. (9) This included supporting the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. However, as Walsingham had feared, Elizabeth proved reluctant to execute her rival. Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has argued that Elizabeth feared that Mary's execution might precipitate the rebellion or invasion which everybody feared. "To kill Mary was also foreign to Elizabeth's accustomed clemency and to her native fear of drastic action." (10)

At this time, one contemporary described him as "a slight, crooked, hump-back young gentleman, dwarfish in stature, but with a face not irregular in feature, and thoughtful and subtle in expression, with reddish hair, a thin tawny beard and large, pathetic greenish-coloured eyes." It is claimed that the Queen called him "my elf" or "my pigmy". (11) Cecil later admitted that if you treasure honour, honesty and peace of mind you should stay out of Tudor politics as it was "a great task to prove one's honesty, and yet not spoil one's fortune." (12)

In February 1588 he was involved in negotiations with Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, in Ostend in the hope of averting war with Spain. He sent detailed observations back to his father, particularly on the build-up of Parma's army for the intended invasion of England. (13) However, the Spanish Armada left Lisbon on 29th May 1588. It numbered 130 ships carrying 29,453 men, of whom some 19,000 were soldiers (17,000 Spanish, 2,000 Portuguese). The plan was to sail to Dunkirk in France where the Armada would pick up another 16,000 Spanish soldiers. (14)

In 1589 Richard Cecil married Elizabeth Brooke, the daughter of William Brooke, 10th Baron Cobham, and his second wife, Frances Newton. Elizabeth had served Queen Elizabeth and had been a maid of honour. William Cecil and Mildred Cecil were delighted with what appears to have been a "love match". They had two children William and Frances, but Elizabeth died eight years after they married during the birth of her third child. (15)

Following the death of Sir Francis Walsingham in 1590, Richard became a more important figure in the government and was knighted in May 1591. Three months later, at the age of twenty-eight, he was elevated to the Privy Council. He was fully committed to the task and in his first year attended 112 meetings out of 164. Cecil was also appointed as high steward of Cambridge University. His father warned him not to question the Queen's judgement. It could be done, but most would be gained by allowing her to make up her own mind. (16)

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, saw the rise of Robert Cecil in the Privy Council as a threat to his own position. According to Richard Rex this illustrated the conflict between the "sword", the old concept of the nobility as based in military service to the Crown, and the "pen", the new concept of service in administration. (17) With his father suffering from poor health, Cecil became more and more important to the Queen. In February 1594, Cecil was described as coming and going constantly to the court "with his hands full of papers and head full of matter", so preoccupied that he "passeth through the chamber like a blind man not looking upon any". (18)

William Cecil, Lord Burghley, was still the Queen's principal councillor but he was growing old. Aware that she would soon need to replace Burghley, on 5th July 1596, she appointed Robert Cecil as her new Secretary of State. Essex was furious as he now realised that he "was no longer her pre-eminent favourite, but just one among her councillors". (19)

Lord Burghley became seriously ill and seemed to be near death. Queen Elizabeth prayed for him daily and frequently visited him. "When the patient's food was brought and she saw that his gouty hands could not lift the spoon, she fed him. (20) Lord Burghley, the only man that Queen Elizabeth probably loved, died at his Westminster house on 4th August 1598. Elizabeth was deeply affected, retiring to her home to weep alone. (21) It is claimed that for the next few months the Privy Council did their best not to mention him at meetings when the Queen was present because it always made her breakdown in tears. (22)

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

In his father's will Cecil received Theobalds and the Hertfordshire estates, but the title, the great house Stamford Baron, and the other estates all went to his half-brother, Thomas Cecil, Burghley's son from his first marriage. Some of his enemies believed that without the support of his father, his political career would go into decline. It was expected that Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, would now become the most significant figure in Queen Elizabeth's government. (23)

However, as Lacey Baldwin Smith, the author of Treason in Tudor England (2006) has pointed out "no matter when Cecil entered the revolving door of Elizabethan politics, he invariably contrived to exit in front of Essex, and to do so while the Earl was safely away from court attempting to win military laurels." (24) Cecil "preferred to pursue a more defensive strategy, with the aim of keeping Spain at arm's length" whereas Essex "represented noble and martial valour". It has been argued that for Essex war "was a form of sport or game; for Cecil it was a source of expense and danger." (25)

Before this happened, Queen Elizabeth, sent Essex to Ireland to deal with Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, who had destroyed an English army at the battle of the Yellow Ford on the Blackwater river. An estimated 900 men were killed including their commander, Henry Bagenal. (26) It was the heaviest defeat the English forces had ever experienced in Ireland. The Queen agreed and gave him a far larger army and more supplies than had been allowed for any previous Irish expedition.

It has been argued that Queen Elizabeth selected the Earl of Essex for this task because he had demonstrated on several occasions his courage and powers of leadership. "More importantly, his popularity gave him an incalculable advantage over the other candidates... Men responded to his name with enthusiasm, and this disposed of the difficulty of raising a large force - an indispensable prerequisite of success. Everyone was eager to serve under Essex." (27)

Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) pointed out that it was not long before Essex realised he had made a serious political mistake: "But almost at once, and long before his forces were embarked, Essex was regarding his appointment with self-pitying bitterness. He had felt he owed it to himself to allow no one else to take it, but he foresaw that once he was over the Irish Sea, his enemies in Council would undermine him... He departed on a tide of popular enthusiasm, the crowd following him for four miles as he rode out of London, but from the outset he bore himself in an injured and almost hostile manner to the Queen and Council." (28)

On 27th March, 1599, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, set off with an army of 16,000 men. He originally intended to attack the Earl of Tyrone in the north, both by sea and by land. On his arrival in Dublin he decided he needed more ships and horses to do this. Information he received suggested he was significantly outnumbered. Essex also feared that Spain would send soldiers to support the 20,000 Irishmen in Tyrone's army. (29)

Essex decided to launch an expedition against Munster and Limerick. Although this did not bring a great deal of success he knighted several of his officers. This upset the Queen as only she had the power to confer knighthoods. (30) This lasted two months and upset Queen Elizabeth who demanded that Essex confronted Tyrone's army. She pointed out that such a large army was costing her £1,000 a day. (31)

Essex insisted he could not do this until more men from England arrived. He also began to worry that his enemies were keeping him short of supplies on purpose: "I am not ignorant what are the disadvantages of absence - the opportunities of practising enemies when they are neither encountered nor overlooked." (32) As a result of military action and especially illness, Essex now only had 4,000 fit men. (33)

Essex reluctantly marched his men north. The two armies faced each other at a ford on the River Lagan. Essex, aware he was in danger of experiencing an heavy defeat, agreed to secret negotiations. (34) The two men announced a truce but it was not known at the what was said during these talks. Essex's enemies back in London began spreading rumours that he was guilty of treachery. It later emerged that Essex had offered without permission, Home Rule for Ireland. (35)

Queen Elizabeth reacted to this news by appointing Robert Cecil to become master of the Court of Wards, a lucrative post that Essex himself had hoped to occupy. Essex wrote to the Queen that "from England I have received nothing but discomfort and soul's wounds" and that "Your Majesty's favour is diverted from me and that already you do bode ill both to me and to it?" (36) According to Pauline Croft this new post "controlled a great array of patronage both at court and in the counties". However, "by far the most significant aspect of his elevation was that it signalled unequivocally that the queen recognized his personal worth and ability". (37)

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, now lost all his power in government. On 7th February, 1601, he was visited by a delegation from the Privy Council and was accused of holding unlawful assemblies and fortifying his house. (38) Fearing arrest and execution he placed the delegation under armed guard in his library and the following day set off with a group of two hundred well-armed friends and followers, entered the city. Essex urged the people of London to join with him against the forces that threatened the Queen and the country. This included Robert Cecil and Walter Raleigh. He claimed that his enemies were going to murder him and the "crown of England" was going to be sold to Spain. (39)

Walter Raleigh attempted to negotiate with rebel kinsman Sir Ferdinando Gorges on boats in the middle of the Thames, "counselling common sense, discretion, and reliance on the queen's clemency". Gorges refused, honouring his commitment to Essex and warning Raleigh of bloody times ahead. While they talked, Essex's stepfather, Sir Christopher Blount aimed four bullets at Raleigh from Essex House, but the optimistic shots missed their target. Recognizing the futility of negotiation, Raleigh hurried to court and mobilized the guard. (40)

At Ludgate Hill his band of men were met by a company of soldiers. As his followers scattered, several men were killed and Blount was seriously wounded. (41) Essex and about 50 men managed to escape but when he tried to return to Essex House he found it surrounded by the Queen's soldiers. Essex surrendered and was imprisoned in the Tower of London. (42)

On 19th February, 1601, Essex and some of his men were tried at Westminster Hall. He was accused of plotting to deprive the Queen of her crown and life as well as inciting Londoners to rebel. Essex protested that "he never wished harm to his sovereign". The coup, he claimed was merely intended to secure access for Essex to the Queen". He believed that if he was able to gain an audience with Elizabeth, and she heard his grievances, he would be restored to her favour. (43)

During the trial, Essex accused Cecil of favouring the right to the English throne of Archduchess Isabella, daughter of Philip II and co-regent with her husband Albert VII. Cecil dramatically interrupted, stepping out from behind a tapestry to beg permission to defend himself from the wild charge. He demanded that Essex reveal his source for the statement. Essex replied that his uncle Sir William Knollys had told him so. However, when Knollys was brought in, he cleared Cecil completely. Cecil, turning to Essex, told him that his malice proceeded from his passion for war, in contrast to Cecil's own desire for peace in the best interests of the country. He continued, "I stand for loyalty, which I never lost: you stand for treachery, wherewith your heart is possessed". Essex was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. (44)

In the early hours of 25th February, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, attended by three priests, sixteen guards and the Lieutenant of the Tower, walked to his execution. In deference to his rank, the punishment was changed to being beheaded in private, on Tower Hill. (45) Essex was wearing doublet and breeches of black satin, covered by a black velvet gown; he also wore a black felt hat. (46) As he knelt before the scaffold Essex made a long and emotional speech of confession where he admitted that he was "the greatest, the most vilest, and most unthankful traitor that ever has been in the land". His sins were "more in number than the hairs" of his head. It took three strokes of the axe to sever his head. (47)

Final Years of Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth was now sixty-years old: "Her nose had slightly thickened, her eyes became sunken, and as she had lost several teeth on the left side of her mouth it was difficult for foreigners to catch her words when she spoke fast, but the impression she made in her last decade was one of astonishing energy for her years. She was erect and active as ever and though her face was wrinkled her skin preserved its flawless white." (48)

Elizabeth, who had difficulty sleeping, often worked before delight with her officials. All measures relating to public affairs were read over to her and she made notes on them, either in her own hand or dictating her comments to secretaries. Robert Cecil discovered he had to be very careful with the way he treated the Queen. During one long meeting with her one evening he noticed she looked tired and suggested that she "must" go to bed. The Queen replied, "Little man, little man, the word must is not to be used to Princes." (49)

Queen Elizabeth, was 67 years-old on 7th September, 1600. When she was younger she enjoyed riding, walking and dancing. However, for the past few years her frequent illnesses had pulled her down alarmingly. Ambassadors reported that she had suffered from fever, gastric attacks and neuralgia. She was described as "very thin", "the colour of a corpse" and that "her bones could be counted". At the opening of Parliament her robes of velvet and ermine were found to be too heavy for her and on the steps of the throne she staggered and was only saved from falling by the peer who stood next to her. (50)

Robert Cecil made strenuous attempts to sort out the Queen's finances that had been badly damaged by recent military adventures. Cecil advocated a foreign policy of peaceful co-existence with other major powers in Europe. When she ascended the throne the ordinary revenue amounted to some £200,000 a year, to which parliamentary subsidies added £50,000. By 1600 ordinary revenue had increased to £300,000, and parliamentary subsidies were now worth £135,000. Yet during this period the Queen's expenditure had gone up far more than her income. This was partly due to inflation. Between 1560 and 1600 prices had risen by at least 75%. (51)

Queen Elizabeth had to constantly appeal to Parliament to grant her more money. However, by 1601 members began to express doubts about whether the country could actually bear so heavy a burden of taxation. They also complained bitterly about Elizabeth's policy of granting of monopolies. These were patents granted to individuals which allowed them to manufacture or distribute certain named articles for their private profit. It was a device by which Elizabeth could confer benefits on favoured courtiers without putting her to any personal expense. (52)

In the 1601 Parliament one member called monopolists "bloodsuckers of the commonwealth" and argued that they brought "the general profit into a private hand". In the last few years the Queen had granted at least thirty new patents on items that included currants, iron, bottles, vinegar, brushes, pots, salt, lead and oil. Francis Bacon suggested that Parliament petition the Queen over this issue but some members wanted to take more direct action. Robert Cecil said he had never seen Parliament like this before: "This is more fit for a grammar school than a court of Parliament". As a result of these complaints proclamations were therefore issued cancelling the principal monopolies. In return, Parliament agreed to impose taxes in order to increase the Queen's income. (53)

Robert Cecil believed that James VI of Scotland was by far the strongest claimant to the English throne, but Elizabeth could not be brought to acknowledge him openly as her heir. In May 1601 Cecil took the decision to begin secret negotiations with James. "The secret correspondence between them was legally treasonable, but Cecil sensed that such a link was the only practical way to ensure in advance that the transition of power, whenever it came, would be peaceful." (54)

Cecil's covert correspondence was in code. Cecil was "10", Elizabeth "24" and James "30". Although he knew the Queen would disapprove of these negotiations he later justified his actions by arguing that "even with strictest loyalty and soundest reason for faithful ministers to conceal sometimes both thoughts and actions from princes when they are persuaded it is for their greater service". He added "if her Majesty had known all I did... her age... joined to the jealously of her sex, might have moved her to think ill of that which helped to preserve her." (55)

Queen Elizabeth's final illness began late in 1602 and thereafter her decline was steady. Robert Cecil wrote to George Nicholson, the Queen's agent in Edinburgh, that Elizabeth "hath good appetite, and neither cough nor fever, yet she is troubled with a heat in her breasts and dryness in her mouth and tongue, which keeps her from sleep, greatly to her disquiet." (56)

Unable to eat much and unwilling to sleep, her last days were difficult. Aware that she was dying Cecil attempted to persuade her to nominate a successor. Believing her unable to speak, they offered to run through a list of candidates and asked her to lift a finger if she wished to approve one. Various names left her unmoved. However, when she got to the name of Edward Seymour, Viscount Beauchamp, she burst into life: "I will have no rascal's son in my seat, but one worthy to be a king." (57)

Soon afterwards an abscess burst in her throat and she recovered a little and was able to sip some broth. Then she declined again and knowing the end was coming, Cecil asked her if she accepted James VI of Scotland as her successor. She had lost the power of speech and merely made a gesture towards her head which they interpreted as one of consent. (58)

Comte de Beaumont, the French ambassador, wrote to King Henry IV on 14th March, that the Queen did not speak for three days. When she regained consciousness she said, "I wish not to live any longer, but desire to die." He added that "she is moreover said to be no longer in her right senses: this, however, is a mistake; she has only had some slight wanderings at intervals." (59)

Four days later Beaumont reported: "The Queen is already quite exhausted, and sometimes, for two or three days together, does not speak a word. For the last two days she has her finger almost always in her mouth, and sits upon cushions, without rising or lying down, her eyes open and fixed on the ground. Her long wakefulness and want of food have exhausted her already weak and emaciated frame, and have produced heat in the stomach, and also the drying up of all the juices, for the last ten or twelve days." (60)

On 24th March, 1603, Archbishop John Whitgift was instructed to visit Queen Elizabeth. The seventy-three year old head of the church knelt by her bed and prayed. After about 30 minutes he attempted to get up but she made a sign that suggested he carried on praying. He did so for another half-hour and when he attempted to rise, the Queen gestured with her hand to keep on the floor. Eventually, she sank into unconsciousness and he was allowed to leave the room. She died later that day. (61)

It was Robert Cecil who read out the proclamation announcing James as the next king of England on the day Elizabeth died, first at Whitehall, then in front of St Paul's Cathedral and a third time at Cheapside Cross. (62) James wrote from Edinburgh informally confirming all the privy council in their positions, adding in his own hand to Cecil, "How happy I think myself by the conquest of so wise a councillor I reserve it to be expressed out of my own mouth unto you". (63)

Cecil remained in London for a short time, to ascertain that there was no outbreak of trouble in the capital or elsewhere over the change of dynasty, and also to make arrangements for Elizabeth's funeral. (64) On Thursday 28th April, a procession of more than a thousand people made its way from Whitehall to Westminster Abbey. "Led by bell-ringers and knight marshals, who cleared the way with their gold staves, the funeral cortege stretched for miles. First came 260 poor women... Then came the lower ranking servants of the royal household and the servants of the nobles and courtiers. Two of the Queen's horses, riderless and covered in black cloth, led the bearers of the hereditary standards... The focal point of the procession was the royal chariot carrying the Queen's hearse, draped in purple velvet and pulled by four horses... On top of the coffin was the life-size effigy of Elizabeth... Sir Walter Raleigh and the Royal Guard walking five abreast, brought up the rear, their halberds held downwards as a sign of sorrow." (65)

King James VI

James VI told Thomas Cecil, 1st Earl of Exeter, that he had full confidence in his half-brother. "He said", reported Thomas, "he heard you were but a little man, but he would shortly load your shoulders with business". Robert Cecil was appointed as the king's Secretary of State. Cecil argued in a letter that he should be given "liberty to negotiate… at home and abroad with friends and enemies in all matters of speech and intelligence". Above all he insisted on the need for complete trust on both sides. "The prince's assurance must be his confidence in the secretary and the secretary's life his trust in the prince… the place of a secretary is dreadful if he serve not a constant prince". (66)

When he opened his first Parliament in March 1604 James reminded members that he was the descendant of the royal houses of both York and Lancaster. "But the union of these two princely houses is nothing comparable to the union of two ancient and famous kingdoms, which is the other inward peace annexed to my person." One member of Parliament, Sir Christopher Pigott, made it quite clear that he was opposed to a union of the two countries. He told the House of Commons the Scots were "beggars, rebels and traitors" who had murdered all the kings. James was furious and ordered him to be sent to the Tower of London. (67)

In November 1604 James VI wrote to Cecil complaining that English officials did not welcome the Scots, for they feared loss of office for themselves. He decided against giving Scotsmen senior posts in his administration. (68) However, he did plan to reward his followers and a total of 158 Scotsman were given positions in his government and household. (69)

Robert Cecil led the successful negotiations with the envoys of Philip III of Spain. The peace brought great benefits to English trade, despite occasional objections from English merchants trading to Spain, who found conditions there much harder than they expected. It enhanced the prosperity of both London and the other ports in England. The 1604 treaty allowed Englishmen to trade and settle in the West Indies and North America. Cecil was rewarded by being given the title of Viscount Cranborne. The following year he became the Earl of Salisbury. (70)

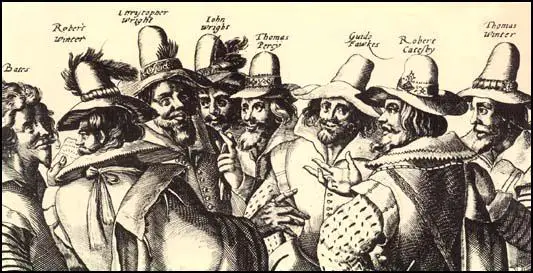

In 1605 Robert Catesby devised the Gunpowder Plot, a scheme to kill James and as many Members of Parliament as possible. At a meeting at the Duck and Drake Inn, Catesby explained his plan to Guy Fawkes, Thomas Percy, John Wright and Thomas Wintour. All the men agreed under oath to join the conspiracy. Over the next few months Francis Tresham, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates and Christopher Wright also agreed to take part in the overthrow of the king. (71)

Catesby's plan involved blowing up the Houses of Parliament on 5th November. This date was chosen because the king was due to open Parliament on that day. At first the group tried to tunnel under Parliament. This plan changed when Thomas Percy was able to hire a cellar under the House of Lords. The plotters then filled the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. The conspirators also hoped to kidnap the king's daughter, Elizabeth. In time, Catesby was going to arrange Elizabeth's marriage to a Catholic nobleman. (72)

One of the people involved in the plot was Francis Tresham. He was worried that the explosion would kill his friend and brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle. On 26th October, Tresham sent Lord Monteagle a letter warning him not to attend Parliament on 5th November. Monteagle became suspicious and passed the letter to Robert Cecil. Cecil quickly organised a thorough search of the Houses of Parliament. While searching the cellars below the House of Lords they found Guy Fawkes and the gunpowder. Fawkes claimed he was John Johnson, the servant of Thomas Percy. (73)

Guy Fawkes was tortured and admitted that he was part of a plot to "blow the Scotsman (James) back to Scotland". On the 7th November, after enduring further tortures, Fawkes gave the names of his fellow conspirators. Fawkes, Everard Digby, Robert Wintour, Thomas Bates, and Thomas Wintour, were all hanged, drawn and quartered. (74)

This is the traditional story of the Gunpowder Plot. However, in recent years some historians have begun to question this version of events. Some have argued that the plot was really devised by Cecil. This version claims that Cecil blackmailed Catesby into organising the plot. It is argued hat Cecil's aim was to make people in England hate Catholics. For example, people were so angry after they found out about the plot, that they agreed to Cecil's plans to pass a series of laws persecuting Catholics. (75)

Cecil's biographer, Pauline Croft, has argued that this is unlikely to have been true: "In the inflamed atmosphere after November 1605, with wild accusations and counter-accusations being traded by religious polemicists, there were allegations that Cecil himself had devised the Gunpowder Plot to elevate his own importance in the eyes of the king, and to facilitate a further attack on the Jesuits. Numerous subsequent efforts to substantiate these conspiracy theories have all failed abysmally." (76)

Robert Cecil definitely took advantage of the situation. Henry Garnett, head of the Jesuit mission in England, was arrested. As Roger Lockyer has pointed out: "The evidence against him was largely circumstantial, but the government was determined to tar all the missionary priests with the brush of sedition in the hope of thereby depriving them of the support of the lay catholic community. A further step in this direction came in 1606, with the drawing up of an oath of allegiance which all catholics were required to take." (77)

Final Years

James VI was a regular visitor to Salisbury's magnificent home, Theobalds. The king loved hunting in the great park and in May 1607 Salisbury agreed to exchange the estate for a grant of other royal properties, most importantly the old palace of Hatfield House. Cecil now spent over £38,000 on its redevelopment. (78) "Salisbury... set out to build a new mansion that was far different in style from the sprawling palace that Lord Burghley had erected. Compact, comfortable, and sumptuously decorated, Hatfield House marked a new departure in English domestic architecture." (79)

Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, took over the Treasury in 1608. He discovered that the King was well over a million pounds in debt and running an annual deficit approaching £100,000. In an effort to solve the problem he increased the number of Impositions (duties on selected imports and exports which were levied by virtue of the royal prerogative and without any parliamentary sanction). As a result of his efforts the debt was substantially reduced, but he could not eliminate it altogether. (80)

Salisbury proposed that Parliament should vote the King a sum of £600,000, so that the debt should be eliminated and a reserve fund established. In return the King would surrender a number of its feudal prerogatives and the reform of the Court of Wards. After several months of haggling the House of Commons agreed that if the Court of Wards was abolished it would provide £200,000 a year. However, when the members consulted their constituents and found that there was widespread opposition to the plan. (81)

It has been argued that Salisbury "bore the brunt of the growing dislike of the Court's financial privileges and the patronage system - and indeed, he was as responsible as anyone for turning the Tudor method of getting things done into the vicious Stuart machine of bribery". (82)

James blamed Salisbury for this failure: "Your greatest error hath been that ye ever expected to draw honey out of gall, being a little blinded with the self-love of your counsel in holding together of this Parliament." (83) Salisbury responded to James by making it clear that he had little more to offer: "I be not able to recover your estate out of the hands of those great wants to which your parliament hath now abandoned you". (84)

Despite these harsh words James showed his appreciation of Salisbury's tireless efforts on his behalf by renewing, for a further nineteen years, the extremely lucrative silk farm concession originally granted in 1601. It is estimated that this concession was worth about £7,000 per annum. (85)

In February 1612, Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, was taken very ill suffering from severe stomach pains. He went to Bath, his condition being made worse by the rattling of the coach on a five days' journey. He then decided to return to London but he failed to arrive, dying of stomach cancer at Marlborough, Wiltshire, on 24th May 1612. (86)

Primary Sources

(1) Anka Muhlstein, Elizabeth I and Mary Stuart (2007)

Robert Cecil was born to be a pen-pusher. He was hunchbacked, having been dropped by his nursemaid and left with permanent curvature of the spine. Unfit to bear arms and engage in athletic pursuits, he received a wholly academic education centred on politics. His father, who had recognised his intellectual ability, groomed him to become his successor.

(2) Peter Ackroyd, Tudors (2012)

Robert Cecil, who at the times of his father's incapacity through illness took on much of the business of government... Essex favoured an agressive foreign policy that supported the cause of international Protestantism; Cecil and his father preferred to pursue a more defensive strategy, with the aim of keeping Spain at arm's length. Essex represented noble and martial valour; Cecil was essentially a career courtier. War for Essex was a form of sport or game; for Cecil it was a source of expense and danger.

(3) Roger Lockyer, Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985)

Robert Cecil's supremacy apparently depended on the Queen's life, for James had no love for the Cecils, whom he held responsible for Elizabeth's refusal to nominate him as her successor. In the last years of the Queen's reign Robert Cecil spent £25,000 on land, to cushion his possible fall from power, but at the same time lie was working hard to make sure that such a fall would not take place. In 1601 he opened secret negotiations with James and prepared arrangements for the peaceful accession of the King of Scots. James's suspicion changed overnight to warm friendship, and when Cecil sent him the draft proclamation announcing his succession, he made no corrections: this music, he said "sounded so sweetly in his ears that he could alter no note in so agreeable an harmony".

By March 1603 the Queen was obviously dying and sat for long periods saying nothing. When, however, Cecil and the other officers of state asked her to name her successor, she was said to have given a sign that she acknowledged James. After that she prayed with Whitgift until she fell into a stupor. Early on the morning of 24 March 1603 she died, and a few hours later, while a messenger rode north as fast as relays of horses could carry him, James was proclaimed King of England.

.

(4) Robert Lacey, Robert, Earl of Essex (1971)

Robert Cecil... was one of the group of Privy Councillors who sat in the House of Commons roughly playing the role of a government front bench... Robert Cecil was unpopular. Even more than his father, he lacked the public graces... He was deformed and easily ridiculed... He bore the brunt of the growing dislike of the Court's financial privileges and the patronage system - and indeed, he was as responsible as anyone for turning the Tudor method of getting things done into the vicious Stuart machine of bribery.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)