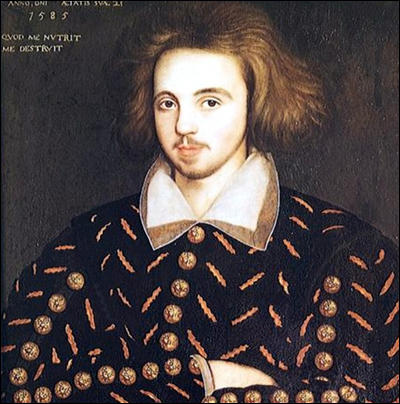

Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, the second of nine children of John Marlowe, a shoemaker, and his wife, Katherine, daughter of William Arthur, was baptized at St George's Church, Canterbury, on 26th February 1564. The spelling of the family name was fluid. Marlowe was sometimes called Marley, Marle, Marlow, Marlo, Marlin, Morley or Merling. (1)

Two months after his birth, Marlowe's father, became a fully-fledged Canterbury citizen. He now became a member of the Fellowship Company Craft of Shoemakers. He was now able to rent a gabled and timber-framed house near Canterbury Cathedral. (2)

As a freeman he had the right to open his own shop, sell his services and enroll apprentices. Thirteen surviving documents reveal that John Marlowe was literate. David Riggs, the author of The World of Christopher Marlowe (2004) comments: "His ability to read is noteworthy but not remarkable. John Marlowe came of age at the historic moment when vast sectors of people who had been excluded from the educational system - small craftsmen, women, servants and apprentices - were learning to read for the first time." (3) John Marlowe was also a parish church-warden. (4)

Records show that in December 1578, Christopher Marlowe was enrolled as a scholar of King's School on a scholarships worth £4 per annum. He was nearly fourteen and so he seems late to be entering the school and may have been a fee-paying pupil before this. (5)

Christian worship played an important role in the school but spent large amounts of time studying Latin and Greek.John Gresshop, the headmaster, had a great influence on him, and introduced Marlowe to the progressive ideas of Roger Ascham and Desiderius Erasmus. However, according to Park Honan, it was the study of classics that really changed him: "Marlowe was dazzled by the classics. Nothing in his imaginative life was to be the same again, and it may be that no discovery he made, and no love he ever felt, affected his mind and feelings so terribly, so unsettling, as the writers of ancient Rome." (6)

Christopher Marlowe at Cambridge University

In 1580 Marlowe went up to Corpus Christi College, on a Parker scholarship. The scholarships had been endowed by Archbishop Matthew Parker, a former master of Corpus; one of them was reserved for a King's School scholar that had been born in Canterbury. The recipients, it was stipulated, "can make a verse" and should have the "skill of song". The fact that the scholars were intended for holy orders was perhaps less congenial to him. His academic career proceeded smoothly enough. He graduated BA in March 1584, though with no great distinction, he was 199th out of 231 candidates. (7)

Marlowe remained at Cambridge University where he wrote poetry. Marlowe's choice of Latin models - the risqué Ovid and the rebellious Lucan - is suggestive of his deviant mentality. During this period he wrote his first play, Dido, Queen of Carthage. It has been claimed that this is the first example of Marlowe's homosexuality. The opening scene "portrays a pederastic Jupiter wooing his lover-boy Ganymede in phrases that resonate with Marlowe's lyric, 'Come live with me and be my love'. Jupiter's love for his minion sets him in opposition to his wife Juno, goddess of marriage." (8)

Richard Baines, who was at university with Marlowe, claims that he was homosexual and quotes him as saying "all they that love not tobacco and boys were fools". His biographer, Charles Nicholl, claims that his homosexuality can be inferred from some of his writings, notably The Troublesome Reign and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second, King of England. "These do not constitute proof, but add up to a convincing probability". (9)

The last payment of Marlowe's scholarship allowance was on 25th March 1587. He received his MA four months later. In his last weeks at Cambridge he met Thomas Fineux. According to a well-informed contemporary, Simon Aldrich, young Fineux fell drastically under Marlowe's spell. Aldrich claimed that Fineux became an atheist and "would go out at midnight into a wood, and fall down upon his knees, and pray heartily that the Devil would come… He learned all Marlowe by heart... Marlowe made him an atheist." (12)

Atheism

Marlowe's first theatrical success in London was his thunderous drama of conquest and ambition, Tamburlaine the Great, based on the exploits of the fourteenth-century Central Asian emperor, Timur. It is believed that it was first performed in the summer of 1587. The play's popularity led to the sequel, The Second Part of the Bloody Conquests of Mighty Tamburlaine. (13)

In 1588 Robert Greene, the popular dramatist of the time attacked the play for its "atheism". As Park Honan points out: "Robert Greene did not stop with a charge of atheism, though that was the most invidious and dangerous of his smears. Unable to reach a wide mass of playgoers, he tried to make Marlowe seem pretentious, absurd, and conceitedly ambitious chiefly to a group of educated fellow wits. Hence his recondite, teasing manner served well, and he probably kept up a refined fire each year until he died." (14)

According to Paul Hyland, Marlowe was a member of "a collection of thinkers, tightly knit or loosely grouped, whose passion was to explore the world and the mind". The group included the geographers, Richard Hakluyt and Robert Hues, the astrologer, Thomas Harriot, the mathematicians, Thomas Allen and Walter Warner, and the writers, Thomas Kyd, George Chapman and Matthew Roydon. The men would either meet at the homes of Walter Raleigh, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, and Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland. (15)

It has been claimed that these men were atheists. In reality they were sceptics (someone who doubts the authenticity of accepted beliefs). For example, at various times the Earl of Oxford was quoted as saying the Bible was "only... to hold men in obedience, and was man's device" and "that the blessed virgin made a fault... and that Joseph was a wittol (cuckold). Oxford did not believe in heaven and hell and declared "that after this life we should be as we had never been and the rest was devised but to make us afraid like babes and children of our shadows". (16)

Robert Persons, a Catholic priest, published Responsio. Published first in Latin, over the next two years it went through eight editions in four languages. It included an attack on Raleigh's group. "There is a flourishing and well known school of Atheism which Sir Walter Raleigh runs in his house, with a certain necromancer as teacher." It then went on to predict that some day an edict might appear in the Queen's name in which belief in God would be denied. Persons claimed that this information came from testimony from "such as live with him, and others that see their lives". He also alleged that William Cecil and other Privy Councillors lived as "mere atheists, and laughing at other men's simplicity in that behalf". (17)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

It has been argued that Raleigh was "prone to expressions of rational scepticism, a potentially dangerous trait given the company he sometimes kept and his inclination towards discussion and debate". He was also known to be in contact with other freethinkers such as Marlowe, Harriot and Hakluyt but Robert Persons was unable to provide any hard evidence against Raleigh. (18)

Mathew Lyons, the author of The Favourite: Raleigh and His Queen (2011) has suggested: "Raleigh was not an atheist as we understand the term: his was a muscular unadorned faith, intense in its privacy and unbreachable in its force... His kind of atheism was, in fact, viewed with perhaps even more distrust and disgust by the Protestant establishment than recusancy, and their horror of such indifference was shared across the religious divide." (19)

John Aubrey later wrote about Thomas Allen, a astrologer and mathematician, and one of the men accused of being in Marlowe's atheist circle: "In those dark times, astrologer, mathematician and conjuror were accounted the same things, and the vulgar did verily believe him to be a conjuror. He had a great many mathematical instruments and glasses in his chamber, which did also confirm the ignorant in their opinion." (20)

It has been argued that while at university Marlowe developed an interest in atheism. Marlowe wrote that "the first beginning of Religion was only to keep men in awe" and his advice "not to be afraid of bugbears and goblins" came from his reading of "Ovid, Lucretius, Polybius and Livy". (21) In one of his plays, Jew of Malta, Marlowe wrote: "I count religion but a childish toy". (22)

Richard Baines, a government spy, later reported that Christopher Marlowe was definitely an atheist. He claimed that he definitely heard Marlowe say that "Christ was a bastard and his mother dishonest". He also said that Marlowe once remarked that "if he were put to write a new religion, he would undertake both a more excellent and admirable method". Finally, he stated that Jesus Christ was a homosexual and "St John the Evangelist was bedfellow to Christ... and that he used him as the sinners of Sodoma". (23)

In the autumn of 1592, Thomas Drury, was interviewed by the authorities about his knowledge of this atheist plot. He made a statement that revealed details about what Richard Cholmeley had told him about figures such as Christopher Marlowe, Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh, Charles Howard and William Cecil. Drury claimed that Cholmeley made accusations against most of the leaders in the government. (24) One of his most important claims was that Marlowe "is able to show more sound reasons for atheism than any divine in England is able to give to prove divinity, and that Marlowe told him, he hath read the atheist lecture to Sir Walter Raleigh and others". (25)

On his deathbed, Robert Greene, admitted that he once was like Marlowe "a scoffer at religion" and had denied the existence of God. He had finally repented and urged Marlowe and other Tudor dramatists to turn aside from this "diabolical atheism". He warned Marlowe to repent while there is still time, for "little knowest thou how in the end thou shalt be visited." (26)

Christopher Marlowe and the Law

In the summer of 1589 Marlowe and Thomas Watson were both living, perhaps as room-mates, in Norton Folgate, Shoreditch. On the afternoon of 18th September, in Hog Lane, Marlowe and Watson fought William Bradley, son of the landlord of The Bishop Inn on Gray's Inn Road, with sword and dagger. (27) During the fighting "Watson lunged and killed Bradley with a thrust that penetrated six inches into the right breast; and then, amidst cries of the crowd, both Watson and Marlowe waited to be arrested." (28)

In the course of this fight Bradley was killed. Marlowe and Watson were committed to Newgate. At the inquest the following day, the Middlesex coroner recorded a verdict of self-defence. Marlowe was now released but Watson remained in prison until he was pardoned by Queen Elizabeth in February, 1590. (29)

In 1591 Christopher Marlowe was living with Richard Baines in the little sea-port of Vlissingen. The following year Marlowe was arrested with Gifford Gilbert, a goldsmith, and both men were accused by Baines of being counterfeiters. Under examination, Marlowe admits that he was with Gilbert when he made a Dutch shilling. However, he claimed that he was only testing out the goldsmith's skills. (30)

It has been argued that Baines had set-up Marlowe: "One day in Flushing, Gifford Gilbert minted a Dutch shilling in pewter, so false in colour that it was clearly designed as a token of his skills. Marlowe perhaps felt resigned to fate; but it appears that by taking Richard Baines at face value he lost sight of his own danger. Baines, by then, had professed warm friendship, goodwill, or an approval of coining; tactically, he may have posed as a man hoping to profit from counterfeiting himself, and so wished the two chamber-mates all success. Whatever he said makes little difference. He misled Marlowe, who grossly misjudged the spy's character and underestimated him." (31)

Richard Baines was believed and Christopher Marlowe, Evan Flud, and Gifford Gilbert, were deported on 26th January 1592. On his return Marlowe was interviewed by William Cecil, Lord Burghley. It is not known what happened at this meeting but he was certainly free by May, 1592. It has been suggested that the reason for this was that he had been working as a spy for Cecil in Europe. (32)

The Massacre at Paris

Marlowe appears to have spent the next couple of months writing The Massacre at Paris. It was apparently performed by Lord Strange's Men in January 1593. The play is a lurid account of the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre that had taken place in 1572. It was "an atrocity ingrained in the mind of English protestants, and no doubt in the mind of the young Marlowe in Canterbury, a city which received a large share of Huguenot refugees, is the most topical and overtly political of his plays." (33)

David Riggs, the author of The World of Christopher Marlowe (2004), believes it is a poor play: "The text looks compressed and improvisatory... The metre often sounds clumsy and the imagery sometimes feels confused. Lines, and sets of lines, are carelessly repeated. When the Queen Mother rouses herself to kill her younger son, she recycles the soliloquy she had used when preparing to poison her older one.... The pace is exceedingly rapid. Two hundred and fifty speeches consist of only one or two lines." (34)

Park Honan points out that Marlowe had set himself a difficult task: "Apart from representing 20,000 murders or so on a stage, he had to picture an immensely complicated panorama of incident and accident, political fissions and shifting alliances. He had to imagine the populace of France, characterize its leaders, and intuit meanings in the debacle." (35) Charles Nicholl agrees and argues that "the fragmentary nature of the text is in part a deliberate technique, in which the brevity and rapidity of the scenes create a vivid kind of reportage: this has been likened to the cinematic style of jump-cutting". (36)

The Death of Christopher Marlowe

In March 1593, Walter Raleigh upset Queen Elizabeth and her Privy Council, by making a speech in the House of Commons against proposed legislation to enforce religious conformity, aimed at both Catholic and Puritan dissenters. "He (Rayleigh) denounced the bill as inquisitorial, an invasion into realms of private opinion and belief that neither could, nor should, be policed." As Charles Nicholl pointed out, his opponents said he was "arguing against religious enforcement in order to protect his own illicit belief: atheism. His plea for tolerance becomes a weapon to use against him, an instance of his own non-conformity." (37)

It is believed that the authorities decided to deal with the people they considered to be atheists. Richard Baines, a government spy, provided information to the Privy Council about his activities. (38) On 20th May 1593 Christopher Marlowe was arrested and charged with blasphemy and treason. His friend, Thomas Kyd, was also taken into custody and after being tortured he made a confession where he claimed that "it was his (Marlowe) custom… to jest at the divine scriptures and strive in argument to frustrate and confute what hath been spoken or written by prophets and such holy men". He also suggested that Marlowe had talked about Jesus Christ and St. John as bedfellows. (39)

Marlowe was allowed bail, on condition that he report daily to the Star Chamber. On the 30th May, 1593, Marlowe was drinking in a tavern in Deptford with Ingram Frizer, Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley. The four men walked in the garden before having a meal together. Frizer had originally said he would pay for the food but later changed his mind. During the argument that followed Frizer stabbed Marlowe above the eyeball. The blade entered Marlowe's brain, killing him instantly. (40)

An Inquest was held on 1st June. William Danby, Coroner for the Queen's Household, presided over the Inquest. In doing so, he acted illegally, since the country coroner was required to be on hand, according to statutory law. (41) According to the report by Danby, "Marlowe suddenly and of malice... unsheathed the dagger... and there maliciously gave the aforesaid Ingram Fritzer two wounds on his head of the length of two inches and of the depth of a quarter of an inch." Danby claimed that Frizer, "in fear of being slain and sitting on the aforesaid bench between Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley so that he was not able to withdraw in any way, in his own defence and to save his life... gave the aforesaid Christopher Marlowe then and there a mortal wound above his right eye of the depth of two inches." (42)

David Riggs has questioned this account: "Since the scalp consists of skin and bone, Frizer's wounds can hardly have been a quarter of an inch deep, nor does Coroner Danby say that Marlowe attacked his companion with the point of his knife. The deposition rather indicates that Marlowe (or someone) pummelled Fritzer's scalp with the hilt of his dagger. This was a common practice in Elizabethan brawls and it had a precise connotation. Pummelling meant that you intended to hurt, but not to kill your adversary. Had Marlowe wanted to kill Fritzer, he would have stabbed him in the back of the neck. Fritzer's scalp wounds were the result of a beating rather than a stabbing." (43)

It was later claimed that Frizer, Skeres and Poley were all government agents. (44) Poley had worked for Sir Francis Walsingham and was a key figure in uncovering the Babington Plot. (45) As well as being spies, Frizer and Skeres, were both involved in money-lending swindles. (46) "Poley, Skerres and Frizer were used to operating in teams and had worked with one another before. They had practical experience in manipulating the law; they knew how to fabricate a trial narrative and maintain it under interrogation." (47)

On 1st July 1593 Frizer was found not guilty of murder for reasons of self defence. (48) Queen Elizabeth pardoned Frizer just two weeks later, a remarkably brief interview for a capital offence. In normal circumstances, people responsible for the death of another individual, would be kept in prison for a much longer period. (49)

Paul Hyland, the author of Raleigh's Last Journey (2003), has suggested that Marlowe was murdered because he was suspected of being about to provide evidence against Walter Raleigh: "Marlowe had had a choice that fatal day at Deptford: to betray Raleigh or be gagged for good. Several gentleman slept more easily once he was dead." (50)

M. J. Trow, the author of Who Killed Kit Marlowe? (2001) argues that government spies such as Richard Cholmeley had discovered evidence that William Cecil and other government figures were "sound atheists", and that Marlowe was killed as part of a cover-up of this fact. (51)

Christopher Marlowe & William Shakespeare

Charles Nicholl argues in his book, The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe (1992). "The affray was a blind: the body that was viewed by the coroner's jury was someone else's. Marlowe was spirited out of the country, and thereafter dedicated his life to writing plays. These plays went out under the nom de plume of William Shakespeare. They contain many acrostics and anagrams that prove they are Marlowe's, but people still go on thinking they are by Shakespeare." (52)

It has been pointed out that the first time the name William Shakespeare is known to have been connected with any literary work whatsoever was with the publication of Venus and Adonis just a week or two after the apparent death of Marlowe. However, according to Scott McCrea, the author of The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question (2005) the overwhelming majority of Shakespeare scholars and literary historians, believe that Marlowe was not involved in the writing of Shakespeare's play. (53)

In October 2016 Oxford University Press decided to credit Marlowe as co-writer of the three Henry VI plays. "Using old-fashioned scholarship and 21st-century computerised tools to analyse texts, the edition’s international scholars have contended that Shakespeare’s collaboration with other playwrights was far more extensive than has been realised until now. Henry VI, Parts One, Two and Three are among as many as 17 plays that they now believe contain writing by other people, sometimes several hands.... Marlowe’s hand in parts of the Henry VI plays has been suspected since the 18th century but this marks the first prominent billing in an edition of Shakespeare’s collected works." (54)

Primary Sources

(1) Park Honan, Christopher Marlowe - Poet and Spy (2005)

Robert Greene did not stop with a charge of atheism, though that was the most invidious and dangerous of his smears. Unable to reach a wide mass of playgoers, he tried to make Marlowe seem pretentious, absurd, and conceitedly ambitious chiefly to a group of educated fellow wits. Hence his recondite, teasing manner served well, and he probably kept up a refined fire each year until he died.

(2) Charles Nicholl, Christopher Marlowe : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

The links, if any, between Marlowe's supposed atheism and the circumstances of his death on 30 May 1593, remain a matter of debate. He was certainly under some kind of government surveillance at the time of his death, having been called before the privy council on 18 May, and ordered to report daily until "licensed to the contrary"...

The case against Marlowe was probably further strengthened by Kyd. Although his statement of Marlowe's "monstrous opinions" was certainly written down after Marlowe's death, it doubtless echoes what Kyd told his interrogators in mid-May.

(3) William Danby, Inquest into the death of Christopher Marlowe (1st June, 1593)

Christopher Marlowe suddenly and of malice... unsheathed the dagger... and there maliciously gave the aforesaid Ingram Fritzer two wounds on his head of the length of two inches and of the depth of a quarter of an inch... In fear of being slain and sitting on the aforesaid bench between Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley so that he was not able to withdraw in any way, in his own defence and to save his life... gave the aforesaid Christopher Marlowe then and there a mortal wound above his right eye of the depth of two inches.

(4) David Riggs, The World of Christopher Marlowe (2004)

Since the scalp consists of skin and bone, Frizer's wounds can hardly have been a quarter of an inch deep, nor does Coroner Danby say that Marlowe attacked his companion with the point of his knife. The deposition rather indicates that Marlowe (or someone) pummelled Fritzer's scalp with the hilt of his dagger. This was a common practice in Elizabethan brawls and it had a precise connotation. Pummelling meant that you intended to hurt, but not to kill your adversary. Had Marlowe wanted to kill Fritzer, he would have stabbed him in the back of the neck. Fritzer's scalp wounds were the result of a beating rather than a stabbing.

(5) Dalya Alberge, The Guardian (23rd October, 2016)

The long-held suggestion that Christopher Marlowe was William Shakespeare is now widely dismissed, along with other authorship theories. But Marlowe is enjoying the next best thing – taking centre stage alongside his great Elizabethan rival with a credit as co-writer of the three Henry VI plays.

The two dramatists will appear jointly on each of the three title pages of the plays within the New Oxford Shakespeare, a landmark project to be published by Oxford University Press this month.

Using old-fashioned scholarship and 21st-century computerised tools to analyse texts, the edition’s international scholars have contended that Shakespeare’s collaboration with other playwrights was far more extensive than has been realised until now.

Henry VI, Parts One, Two and Three are among as many as 17 plays that they now believe contain writing by other people, sometimes several hands. It more than doubles the figure in the previous Oxford Shakespeare, published 30 years ago.

Marlowe’s hand in parts of the Henry VI plays has been suspected since the 18th century but this marks the first prominent billing in an edition of Shakespeare’s collected works.

A team of 23 academics from five countries completed the research, headed by four professors as general editors: Gary Taylor (Florida State University, US) John Jowett (Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham), Terri Bourus (Indiana University, Indianapolis, US) and Gabriel Egan (De Montfort University, Leicester).

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)