Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus was born in Rotterdam in 1466. He was illegitimate and his father, Roger Gerard, was a well-educated priest, and his mother, a widow named Margaretha Rogerius. His parents died of the plague in 1483 and his guardians "apparently because they had embezzled his money cajoled him into becoming a monk at the monastery of Steyr, a step which he regretted all the rest of his life." (1)

Erasmus developed a love of learning and while at the monastery he wrote: "I consider as lovers of books not those who keep their books hidden in their store-chests and never handle them, but those who, by nightly as well as daily use thumb them, batter them, wear them out, who fill out all the margins with annotations of many kinds, and who prefer the marks of a fault they have erased to a neat copy full of faults." (2)

At the monastery he met a young man, Servatius Rogerus, to whom he became particulary attached. He told his brother, Pieter Gerard: "He is, believe me, a youth of beautiful, disposition and very agreeable personality and a devoted student... This young man is very anxious to meet you, and if you make your way have soon, as I hope you will, I am quite sure that you will not only think he deserves your friendship but readily prefer him to me, your brother, for I well know both your warm-heartedness and his goodness." (3)

Erasmus wrote a series of letters to Rogerus detailing the depth of his affection and attachment. At first Rogerus seems to have responded to these advances with equal ardour, but then pulled back from a sexual relationship. Erasmus was extremely hurt by this rejection: "So impossible is it, dear Servatius, that anything should suffice to wash away the cares of the spirit and cheer my heart when I am deprived of you, and you alone... But you, crueller than any tigress, can easily dissemble all this as if you had no care for your friend's well-being at all. Ah, heartless spirit! Alas, unnatural man." (4)

It has been argued by Jonathan Goldberg, in his book, Queering the Renaissance (1993) that these letters suggest a homosexual relationship. However, Diarmaid MacCulloch, the author of Reformation: A History (2003) claims that this is a misunderstanding about the nature of male relationship in the 15th century and the letters are only "surely expressions of true friendship" and that it was not uncommon during this period for men to express passionate attachments to your close friends." (5)

Desiderius Erasmus: Catholic Priest

Erasmus took vows in 1488 and was ordained to the Catholic priesthood on 25th April 1492. According to his biographer, Johan H. Huizinga: "He found society, and especially religious life, full of practices, ceremonies, traditions and conceptions, from which the spirit seems to have departed. He does not reject them offhand and altogether; what revolts him is that they are so often performed without understanding and right feeling. But to his mind, highly susceptible to the foolish and ridiculous things, and with a delicate need of high decorum and inward dignity, all that sphere of ceremony and tradition displays itself as a useless, nay, a hurtful scene of human stupidity and selfishness." (6)

In 1493, he became secretary to the Bishop of Cambrai, who was Chancellor of the Order of the Golden Fleece. This gave him the opportunity to leave the monastery and travel. In 1495 Erasmus went to the University of Paris and became an accomplished Latinist. Erasmus particularly admired Lorenzo Valla, "on account of his book on the elegancies of the Latin language". Valla was considered to be one of the leaders of Renaissance Humanism (a revival in the study of classical antiquity). Erasmus shared Valla's dislike "medieval scholasticism" and promoted the study of the humanities: grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. (7)

Erasmus also met and influenced by John Colet, canon of St Martin le Grand, London. Colet introduced Erasmus to the work of Plato. He later recalled that "when Colet speaks I might be listening to Plato!" (8) For people like Erasmus and Colet the "individual's personal relationship to God was now more important than his relationship to the church as an organization". (9)

Erasmus wrote to Christian Northoff about how much he enjoyed his studies: "A constant element of enjoyment must be mingled with our studies, so that we think of learning as a game rather than a form of drudgery, for no activity can be continued for long if it does not to some extent afford pleasure to the participant.... You must acquire the best knowledge first, and without delay; it is the height of madness to learn what you will later have to unlearn…. Do not be guilty of possessing a library of learned books while lacking learning yourself." (10) In a letter to Jacob Batt he explained how much he valued books: "When I get a little money I buy books; and if any is left I buy food and clothes." (11)

Christian Humanism

In 1499 Erasmus made his first visit to England where he resumed his friendship with Colet. He introduced him to Thomas More, a member of Lincoln's Inn. According to Roger Lockyer: "With them the humanist movement in England - the study of man and his relationship to God - came of age." (12) John Guy agrees that Erasmus did have a great influence over More, Cuthbert Tunstall, Richard Pace, Thomas Linacre, and William Grocyn. However, "Erasmus aspired to 'peace of mind' and 'moderate reform' through the application and development of critical insight and the power of humane letters. He eschewed politics; some said he was a dreamer. Colet, More, Tunstall, and Pace, by contrast, became councillors to Henry VIII: they resolved to enter politics and Erasmus disapproved, predicting the misfortunes that befell those who put their trust in princes." (13)

During a stay in Tournehem, a castle near Saint-Omer in France, Erasmus encountered a badly behaved, yet friendly soldier who was an acquaintance of James Battus. On the request of the soldier's wife, who was upset by her husband's behaviour, Battus asked Erasmus to write a text which would convince the soldier of the necessity of mending his ways. He began Handbook of the Christian Knight (1503): "Albeit, most virtuous father, that the little book... which I made for myself only, and for a certain friend of mine being utterly unlearned, hath begun to mislike and displease me the less, forasmuch as I do see that it is allowed of you and other virtuous and learned men such as you be, of whom (as ye are indeed endued with godly learning, and also with learned godliness) I know nothing to be approved, but that which is both holy and also clerkly: yet it hath begun well nigh also to please and like me now, when I see it (after that it hath been so oftentimes printed) yet still to be desired and greatly called for, as if it were a new work made of late: if so be the printers do not lie to flatter me withal." (14)

During his studies Erasmus began collecting Greek and Latin proverbs. The first edition, Adagia, was published in 1500. A second and expanded edition, entitled Adagiorum, was published in 1508. It confirmed Erasmus' vast reading in ancient literature. It included over 3,000 proverbs, some accompanied by richly annotated commentaries, some of which were brief essays on political and moral topics. Charles Speroni has described it as "one of the most monumental collection of proverbs ever assembled" (15)

It included proverbs such as: More haste, less speed. The blind leading the blind. A rolling stone gathers no moss. One man's meat is another man's poison. Necessity is the mother of invention. One step at a time. To be in the same boat. To lead one by the nose. A rare bird. One to one. Out of tune. A point in time. I gave as bad as I got. To call a spade a spade. Hatched from the same egg. Many hands make light work. Where there's life, there's hope. To cut to the quick. Time reveals all things. Crocodile tears. To lift a finger. Kill two birds with one stone. The bowels of the earth. Happy in one's own skin. Hanging by a thread. To throw cold water on. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. No sooner said than done. Between a rock and a hard place. Can't teach an old dog new tricks. A necessary evil. To squeeze water out of a stone. To leave no stone unturned. God helps those who help themselves. The grass is greener over the fence. The cart before the horse. One swallow doesn't make a summer. To sleep on it. To break the ice. Ship-shape. To die of laughing. To have an iron in the fire. To look a gift horse in the mouth. Like father, like son. He blows his own trumpet. A snail's pace. The most disadvantageous peace is better than the most just war. (16)

While in England he taught Greek at Cambridge University and began translating the works of Cicero and Seneca. He became a strong supporter of John Colet who in 1512 preached before the Canterbury Convocation. He attacked clerical abuses and advocated reform of the church from within. Colet compared negligent priests of heretics. (17) "You are come together today, fathers and right wise men, to hold a council. In which what you will do and what matters you will handle, I do not yet know, but I wish that, at length, mindful of your name and profession, you would consider of the reformation of ecclesiastical affairs; for never was there more necessity and never did the state of the Church more need endeavours. Wherefore I have come here today, fathers, to admonish you with all your minds to deliberate, in this your Council, concerning the reformation of the Church. As I am about to exhort you, revered fathers, to endeavour to reform the condition of the Church; because nothing has so disfigured the face of the Church as the secular and worldly way of living on the part of the clergy... As to the second worldly evil, which is the lust for the flesh - has not this vice, I ask, inundated the Church as with the flood of its lust, so that nothing is more carefully sought after, in these most troubled times, by the most part of priests, than that which ministers sensual pleasure? They give themselves to feasting and banqueting; spend themselves in vain babbling, take part in sports and plays, devote themselves to hunting and hawking; are drowned in the delights of this world; patronize those who cater for their pleasure." (18)

The sermon aroused resentment, but the humanists repeated their demand for religious renewal. "Erasmus best combined the Christian and classical elements of the Renaissance; the key to his success was his exquisite style: the medium was as important for him as the message. He embellished his evangelism with racy criticisms of priests and monks, superstition and empty ritual, scholastic theologians, and even the mores of the papacy, but was careful to insinuate and thereby avoid dangerous statements." (19)

The Praise of Folly

Erasmus most important book was The Praise of Folly. He wrote it in the home of Thomas More. "The book is spoken by Folly in her own person… She counsels, as an antidote to wisdom, “taking a wife, a creature so harmless and silly, and yet so useful and convenient, as might mollify and make pliable the stiffness and morose humour of men'. Who can be happy without flattery or without self-love? Yet such happiness is folly. The happiest men are those who are nearest the brutes and divest themselves of reason. The best happiness is that which is based on delusion, since it costs least… There are passages where the satire gives way to invective, and Folly utters the serious opinions of Erasmus; these are concerned with ecclesiastical abuses. Pardons and indulgences, by which priests 'compute the time of each souls’s residence in purgatory'; the worship of saints, even of the Virgin, 'whose blind devotees think it manners to place the mother before the Son'; the disputes of theologians as the Trinty and the Incarnation; the doctrine of transubstantiation; the scholastic sects; popes, cardinals, and bishops – all are fiercely ridiculed. Particularly fierce is the attack on the monastic orders; they are 'brainsick fools', who have very little religion in them, yet are 'highly in love with themselves, and fond admirers of their own happiness'. It might be supposed, from such passages, that Erasmus would have welcomed the Reformation, but it proved otherwise." (20)

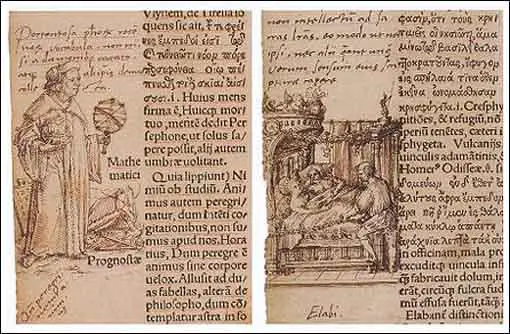

The first edition of The Praise of Folly (1515) included illustrations by Hans Holbein. Apparently Pope Leo X found this satire amusing. However, some of his friends warned him that as he attacked established religion he faced possible dangers to his safety. The Russian philosopher, Mikhail Bakhtin has argued: "The satirist whose laughter is negative places himself above the object of his mockery, he is opposed to it. The wholeness of the world’s comic aspect is destroyed, and that which appears comic becomes a private reaction. The people’s ambivalent laughter, on the other hand, expresses the point of view of the whole world; he who is laughing also belongs to it.. Medieval Latin humour found its final and complete expression at the highest level of the Renaissance in Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly, one of the greatest creations of carnival laughter in world literature." (21)

In his letters he began to speculate on the subject of love. In a letter to Martin Dorp he compares his own views with those of Plato. "I first mention three madnesses of Plato among which the happiest is that of the lovers which is nothing but a kind of ecstasy. But the ecstasy of the pious is nothing else but a foretaste of the future happiness through which we shall be absorbed into God, being in Him rather than in ourselves. But Plato calls this madness when a person is driven out of himself and lives in that which he loves and enjoys it." (22)

Erasmus questioned the official view of sexual morality: "I have no patience with those who say that sexual excitement is shameful and that venereal stimuli have their origin not in nature, but in sin. Nothing is so far from the truth. As if marriage, whose function cannot be fulfilled without these incitements, did not rise above blame. In other living creatures, where do these incitements come from? From nature or from sin? From nature, of course. It must be borne in mind that in the appetites of the body there is very little difference between man and other living creatures. Finally, we defile by our imagination what of its own nature is fair and holy. If we were willing to evaluate things not according to the opinion of the crowd, but according to nature itself, how is it less repulsive to eat, chew, digest, evacuate, and sleep after the fashion of dumb animals, than to enjoy lawful and permitted carnal relations?" (23)

He remained highly critical of monasteries: "There are monasteries where there is no discipline, and which are worse than brothels. There are others where religion is nothing but ritual; and these are worse than the first, for the Spirit of God is not in them, and they are inflated with self-righteousness. There are those, again, where the brethren are so sick of the imposture that they keep it up only to deceive the vulgar. The houses are rare indeed where the rule is seriously observed, and even in these few, if you look to the bottom, you will find small sincerity. But there is craft, and plenty of it - craft enough to impose on mature men, not to say innocent boys; and this is called profession. Suppose a house where all is as it ought to be, you have no security that it will continue so. A good superior may be followed by a fool or a tyrant, or an infected brother may introduce a moral plague. True, in extreme cases a monk may change his house, or even may change his order, but leave is rarely given. There is always a suspicion of something wrong, and on the least complaint such a person is sent back." (24)

Martin Luther

In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar arrived in Wittenberg. He was selling documents called indulgences that pardoned people for the sins they had committed. Tetzel told people that the money raised by the sale of these indulgences would be used to repair St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Luther was very angry that Pope Leo X was raising money in this way. He believed that it was wrong for people to be able to buy forgiveness for sins they had committed. Martin Luther, professor in biblical studies at University of Wittenberg, wrote a letter to the Bishop of Mainz, Albert of Brandenburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. (25)

On 31st October, 1517, Martin Luther affixed to the castle church door, which served as the "black-board" of the university, on which all notices of disputations and high academic functions were displayed, his Ninety-five Theses. The same day he sent a copy of the Theses to the professors of the University of Mainz. They immediately agreed that they were "heretical". (26) For example, Thesis 86, asks: "Why does not the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?" (27)

At first Erasmus gave Luther his support. Erasmus described him as "a mighty trumpet of gospel truth" while agreeing, "It is clear that many of the reforms for which Luther calls are urgently needed." The feelings were mutual and Luther spoke about Erasmus' superior learning and Luther expressed boundless admiration for all Erasmus had done in the cause of a sound and reasonable Christianity and urged him to join the Lutheran party. Erasmus declined to commit himself, arguing that to do so would endanger his position as a leader in the movement for pure scholarship which he regarded as his purpose in life. (28)

During 1518 Martin Luther wrote a number of tracts criticising the Papal indulgences, the doctrine of Purgatory, and the corruptions of the Church. "He had launched a national movement in Germany, supported by princes and peasants alike, against the Pope, the Church of Rome, and its economic exploitation of the German people." (29) On 15th June 1520, Pope Leo X issued Exsurge Domine, condemning the ideas of Martin Luther as heretical and ordering the faithful to burn his books. Luther responded by burning books of canon law and papal decrees. On 3rd January 1521 Luther was excommunicated. However, most German citizens supported Luther against the Pope. The German papal legate wrote: "All Germany is in revolution. Nine tenths shout Luther as their war-cry; and the other tenth cares nothing about Luther, and cries: Death to the court of Rome!" (30)

Each side tried to enlist Erasmus in this dispute. He finally rejected the Protestant Reformation and came down on the Catholic side. Although he favoured reform he feared war between the two religious groups. In 1524 he wrote a work defending free will, which Luther rejected. Luther replied savagely, and Erasmus was driven further into reaction. According to Bertrand Russell: "He (Erasmus) had always been timid, and the times were no longer suited to timid people. For honest men, the only honourable alternatives were martyrdom or victory." (31)

Humanists like Erasmus had criticised the Catholic Church but Luther's attack was very different. As Jasper Ridley has pointed out: "From the beginning there was a fundamental difference between Erasmus and Luther, between the humanists and the Lutherans. The humanists wished to remove the corruptions and to reform the Church in order to strengthen it; the Lutherans, almost from the beginning, wished to overthrow the Church, believing that it had become incurably wicked and was not the Church of Christ on earth." (32)

Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) argues that: "Erasmus was quite serious about the need to careen the Christian ship, removing all the barnacles and weed which had accumulated over the centuries and cutting out worm-ridden timber. He pleaded for a return to simple faith and devotion not dependent on externals. Yet he had no intention of going to the stake for the cause of reform and he hoped by satirising all aspects of society, secular as well as sacred, to get his point across without causing too much offence." (33)

Martin Luther married Katharina von Bora in 1525. In a letter to François Dubois he defended Luther against the rumours that circulated about him: "There is no doubt about Martin Luther's marriage, but the rumour about his wife's early confinement is false; she is said however to be pregnant now. If there is truth in the popular legend, that Antichrist will be born from a monk and a nun (which is the story these people keep putting about), how many thousands of Antichrists the world must have already!" (34)

Desiderius Erasmus died in Basel on 12th July, 1536. Much of his estate he left to a friend, Boniface Amerbach, for distribution to promising young scholars and to provide dowries for young women without money. He died without a priest or confessor, and left no money to have masses said for his soul. "He was buried in the same church where reformers had destroyed religios statues and images seven years earlier." (35)

Hugh Trevor-Roper pointed out: "Desiderius Erasmus was a scholar who, in the early days of printing, sought to give his contemporaries clear and accurate texts of certain neglected works…. His personal character was not heroic. He was a valetudinarian, comfort-loving, timid and querulous. He lived in his study and died in his bed. And yet Erasmus is a giant figure in the history of ideas. He is the intellectual hero of the sixteenth century, and his failure was Europe’s tragedy. For his failure seemed, at the time, immense and final: as immense as his previous success." (36)

Primary Sources

(1) Desiderius Erasmus, letter to an unidentified friend (1489)

I consider as lovers of books not those who keep their books hidden in their store-chests and never handle them, but those who, by nightly as well as daily use thumb them, batter them, wear them out, who fill out all the margins with annotations of many kinds, and who prefer the marks of a fault they have erased to a neat copy full of faults.

(2) Desiderius Erasmus, letter to letter to Christian Northoff (1497)

A constant element of enjoyment must be mingled with our studies, so that we think of learning as a game rather than a form of drudgery, for no activity can be continued for long if it does not to some extent afford pleasure to the participant...

You must acquire the best knowledge first, and without delay; it is the height of madness to learn what you will later have to unlearn…. Do not be guilty of possessing a library of learned books while lacking learning yourself.

(4) Desiderius Erasmus, letter to Jacob Batt (12 April 1500)

When I get a little money I buy books; and if any is left I buy food and clothes.

(5) Desiderius Erasmus, Handbook of the Christian Knight (1503)

For we have in Latin only a few small streams and muddy puddles, while they have pure springs and rivers flowing in gold. I see that it is utter madness even to touch with the little finger that branch of theology that deals chiefly with the divine mysteries, unless one is also provided with the equipment of Greek.

(6) Desiderius Erasmus, Adagiorum (1508)

In the country of the blind the one-eyed man is king.

(7) Desiderius Erasmus, Adagiorum (1508)

The most disadvantageous peace is better than the most just war.

(8) Desiderius Erasmus, Adagiorum (1508)

He that gives quickly gives twice.

(9) Desiderius Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (1511)

For what is life but a play in which everyone acts a part until the curtain comes down?

(10) Desiderius Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (1511)

This type of man who is devoted to the study of wisdom is always most unlucky in everything, and particularly when it comes to procreating children; I imagine this is because Nature wants to ensure that the evils of wisdom shall not spread further throughout mankind.

(11) Desiderius Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (1511)

It might be wiser for me to avoid Camarina and say nothing of theologians. They are a proud, susceptible race. They will smother me under six hundred dogmas. They will call me heretic and bring thunderbolts out of their arsenals, where they keep whole magazines of them for their enemies. Still they are Folly's servants, though they disown their mistress. They live in the third heaven, adoring their own persons and disdaining the poor crawlers upon earth. They are surrounded with a bodyguard of definitions, conclusions, corollaries, propositions explicit, and propositions implicit. ...They will tell you how the world was created. They will show you the crack where Sin crept in and corrupted mankind.

(12) Desiderius Erasmus, The Praise of Folly (1511)

They (the theologians) will explain to you how Christ was formed in the Virgin's womb; how accident subsists in synaxis without domicile in place. The most ordinary of them can do this. Those more fully initiated explain further whether there is an instance in Divine generation; whether in Christ there is more than a single filiation; whether 'the Father hates the Son' is a possible proposition; whether God can become the substance of a woman, of an ass, of a pumpkin, or of the devil, and whether, if so, a pumpkin could preach a sermon, or work miracles, or be crucified. And they can discover a thousand other things to you besides these. They will make you understand notions, and instants, formalities, and quiddities, things which no eyes ever saw, unless they were eyes which could see in the dark what had no existence.

(13) Desiderius Erasmus, Ciceronianus (1511)

We must learn how to imitate Cicero from Cicero himself. Let us imitate him as he imitated others.

(14) Desiderius Erasmus, Ciceronianus (1511)

A speech comes alive only if it rises from the heart, not if it floats on the lips.

(15) Desiderius Erasmus, letter to Martin Dorp (1515)

I first mention three madnesses of Plato among which the happiest is that of the lovers which is nothing but a kind of ecstasy. But the ecstasy of the pious is nothing else but a foretaste of the future happiness through which we shall be absorbed into God, being in Him rather than in ourselves. But Plato calls this madness when a person is driven out of himself and lives in that which he loves and enjoys it.

(16) Desiderius Erasmus, letter to Lambertus Grunnius (August 1516)

There are monasteries where there is no discipline, and which are worse than brothels. There are others where religion is nothing but ritual; and these are worse than the first, for the Spirit of God is not in them, and they are inflated with self-righteousness. There are those, again, where the brethren are so sick of the imposture that they keep it up only to deceive the vulgar. The houses are rare indeed where the rule is seriously observed, and even in these few, if you look to the bottom, you will find small sincerity. But there is craft, and plenty of it - craft enough to impose on mature men, not to say innocent boys; and this is called profession. Suppose a house where all is as it ought to be, you have no security that it will continue so. A good superior may be followed by a fool or a tyrant, or an infected brother may introduce a moral plague. True, in extreme cases a monk may change his house, or even may change his order, but leave is rarely given. There is always a suspicion of something wrong, and on the least complaint such a person is sent back.

(17) Desiderius Erasmus, In Praise of Marriage (1519)

I have no patience with those who say that sexual excitement is shameful and that venereal stimuli have their origin not in nature, but in sin. Nothing is so far from the truth. As if marriage, whose function cannot be fulfilled without these incitements, did not rise above blame. In other living creatures, where do these incitements come from? From nature or from sin? From nature, of course. It must be borne in mind that in the appetites of the body there is very little difference between man and other living creatures. Finally, we defile by our imagination what of its own nature is fair and holy. If we were willing to evaluate things not according to the opinion of the crowd, but according to nature itself, how is it less repulsive to eat, chew, digest, evacuate, and sleep after the fashion of dumb animals, than to enjoy lawful and permitted carnal relations?

(18) Desiderius Erasmus, letter to George Halewin (1520)

The soul exists more truly than does the body. Although the philosopher removes himself from the perceptible things and practices the contemplation of things intelligible he does not completely enjoy them except when the soul, fully freed from the material organs through which it now operates, exercises its full force.

(19) Desiderius Erasmus, A Sponge Against Spergines Hutteni (1523)

I am a lover of liberty. I will not and I cannot serve a party.

(20) Desiderius Erasmus, letter to François Dubois (13 March 1526)

There is no doubt about Martin Luther's marriage, but the rumour about his wife's early confinement is false; she is said however to be pregnant now. If there is truth in the popular legend, that Antichrist will be born from a monk and a nun (which is the story these people keep putting about), how many thousands of Antichrists the world must have already!

(21) Desiderius Erasmus, On Education for Children (1529)

Animals only follow their natural instincts; but man, unless he has experienced the influence of learning and philosophy, is at the mercy of impulses that are worse than those of a wild beast. There is no beast more savage and dangerous than a human being who is swept along by the passions of ambition, greed, anger, envy, extravagance, and sensuality.

(22) Desiderius Erasmus, unknown source (c. 1500-1530)

Wherever you encounter truth, look upon it as Christianity.

(23) Desiderius Erasmus, unknown source (c. 1500-1530)

There is nothing I congratulate myself on more heartily than on never having joined a sect.

(24) Desiderius Erasmus, unknown source (c. 1500-1530)

I am a citizen of the world, known to all and to all a stranger.

(25) Desiderius Erasmus, unknown source (c. 1500-1530)

I doubt if a single individual could be found from the whole of mankind free from some form of insanity. The only difference is one of degree. A man who sees a gourd and takes it for his wife is called insane because this happens to very few people.

(26) Desiderius Erasmus, unknown source (c. 1500-1530)

You venerate the saints, and you take pleasure in touching their relics. But you disregard their greatest legacy, the example of a blameless life. No devotion is more pleasing to Mary than the imitation of Mary's humility. No devotion is more acceptable and proper to the saints than striving to imitate their virtues.

(27) James Anthony Froude, Life and Letters of Erasmus (1895)

Erasmus advises students to read only the best books on the subjects with which they are occupied. He cautions them against loading their memories with the errors of inferior writers which they will afterwards have to throw off and forget. The best description of the state of Europe in the age immediately preceding the Reformation will be found in the correspondence of Erasmus himself. I can promise my own readers that if they will accept Erasmus for a guide in that entangled period, they will not wander far out of the way.

(28) Johan H. Huizinga, Erasmus of Rotterdam (1924)

What made Erasmus the man from whom his contemporaries expected their salvation, on whose lips they hung to catch the word of deliverance? He seemed to them the bearer of a new liberty of the mind, a new clearness, purity and simplicity of knowledge, a new harmony of healthy and right living. He was to them as the possessor of newly discovered, untold wealth which he had only to distribute… He found society, and especially religious life, full of practices, ceremonies, traditions and conceptions, from which the spirit seems to have departed. He does not reject them offhand and altogether; what revolts him is that they are so often performed without understanding and right feeling. But to his mind, highly susceptible to the foolish and ridiculous things, and with a delicate need of high decorum and inward dignity, all that sphere of ceremony and tradition displays itself as a useless, nay, a hurtful scene of human stupidity and selfishness.

(29) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946)

The only book by Erasmus that is still read is The Praise of Folly… The book is spoken by Folly in her own person… She counsels, as an antidote to wisdom, “taking a wife, a creature so harmless and silly, and yet so useful and convenient, as might mollify and make pliable the stiffness and morose humour of men”. Who can be happy without flattery or without self-love? Yet such happiness is folly. The happiest men are those who are nearest the brutes and divest themselves of reason. The best happiness is that which is based on delusion, since it costs least…

There are passages where the satire gives way to invective, and Folly utters the serious opinions of Erasmus; these are concerned with ecclesiastical abuses. Pardons and indulgences, by which priests “compute the time of each souls’s residence in purgatory”; the worship of saints, even of the Virgin, “whose blind devotees think it manners to place the mother before the Son”; the disputes of theologians as the Trinty and the Incarnation; the doctrine of transubstantiation; the scholastic sects; popes, cardinals, and bishops – all are fiercely ridiculed. Particularly fierce is the attack on the monastic orders; they are “brainsick fools”, who have very little religion in them, yet are “highly in love with themselves, and fond admirers of their own happiness”. It might be supposed, from such passages, that Erasmus would have welcomed the Reformation, but it proved otherwise.

(30) Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and his World (2009)

The satirist whose laughter is negative places himself above the object of his mockery, he is opposed to it. The wholeness of the world’s comic aspect is destroyed, and that which appears comic becomes a private reaction. The people’s ambivalent laughter, on the other hand, expresses the point of view of the whole world; he who is laughing also belongs to it...

Medieval Latin humour found its final and complete expression at the highest level of the Renaissance in Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly, one of the greatest creations of carnival laughter in world literature.

(31) Paul Oskar Kristeller, Renaissance Quarterly (1970)

In defending the study of the ancients, Erasmus recommends the Platonists above ancient philosophers because they are nearest in style and content to the Bible. Speaking in his own name, Erasmus stresses that man is composed of a soul and a body. The body is akin to the animals, is pleased with visual objects, and has a downward tendency. The soul on the other hand, is akin to the divine and has an upward tendency. “It despises things that can be seen; for it knows that they are perishable, it seeks things which truly are, which always are. Being immortal, it loves things immortal.”

(32) Hugh Trevor-Roper, Men and Events: Historical Essays (1977)

Desiderius Erasmus was a scholar who, in the early days of printing, sought to give his contemporaries clear and accurate texts of certain neglected works…. His personal character was not heroic. He was a valetudinarian, comfort-loving, timid and querulous. He lived in his study and died in his bed. And yet Erasmus is a giant figure in the history of ideas. He is the intellectual hero of the sixteenth century, and his failure was Europe’s tragedy. For his failure seemed, at the time, immense and final: as immense as his previous success.

(33) Robert M. Adams, Draining and Filling: A Few Benchmarks in the History of Humanism (1989)

During the dark ages of religious warfare in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Catholic militants put Erasmus’s books on the Index Expurgatorius, and the few lingering Erasmians took essentially to the closet. Though few of them were martyred, the humanist ideas and valued they had espoused went into eclipse. But in the eighteenth century, the skies cleared.

(34) J. M. Coetzee, Erasmus’s Praise of Folly: Rivalry and Madness (1992)

Erasmus dramatizes a well-established political position: that of the fool who claims license to criticize all and sundry without reprisal, since his madness defines him as not fully a person and therefore not a political being with political desires and ambitions. The Praise of Folly, therefore sketches the possibility of a position for the critic of the scene of political rivalry, a position not simply impartial between the rivals but also, by self-definition, off the stage of rivalry altogether.

(35) David Attwell, J. M. Coetzee and the Idea of the Public Intellectual (2006)

Erasmus’s Moria… sees through the madness of those who see themselves as reasonable and self-possessed while in reality giving themselves over to rivalry.

As a representative of both the feminine and the parodic, Moria does not set out to expose or destroy social conventions: her wisdom lies in working with them, without being ruled by them.

What is the position of someone who sees behind the masks, but refuses to expose them violently? … The Praise of Folly marks out such a position, ‘prudently disarming itself in advance, keeping its phallus the size of the woman’s, steering clear of the play of power, clear of politics.

(36) Anthony Grayling, The History of Philosophy (2019)

The humanistic spirit of the renaissance; Erasmus affords a prime example of one who was able to acknowledge this conformity with his ortho-practic Catholicism. And the focus on human nature, and refreshed ideas about the possibility of finding joy and satisfaction in the flesh in this world, gave an impetus to painting, sculpture and poetry that we would not be without. That is unarguably the greatest contribution of Renaissance humanistic and ethical thought.