King Harold of Wessex

Harold Godwinson, the son of Godwin and his wife, Gytha, was probably born in 1022. There is some evidence to suggest that Godwin was the son of the late tenth-century renegade and pirate Wulfnoth Cild of Compton, West Sussex, who had rebelled against Ethelred the Unready. (1)

Godwin was a strong supporter of King Cnut the Great, and in 1018 he was given the title of Earl of Wessex. Cnut commented that he found Godwin "the most cautious in counsel and the most active in war".

King Cnut took Godwin to Denmark, where he "tested more closely his wisdom", and "admitted him to his council". Cnut introduced him to Gytha. Her brother Ulf, was married to Cnut's sister. (2)

Godwin married Gytha, in about 1020. She gave birth to a least six sons: Harold, Swein, Tostig, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth; and three daughters: Edith, Gunhild and Elfgifu. The birth dates of the children are unknown. (3)

During Harold's childhood his father held an important positioned, helping, along with Earl Siward of Northumbria and Earl Leofric of Mercia, to govern England during the king's extended absences. In 1042, Godwin helped to arrange for Edward the Confessor, the seventh son of Ethelred the Unready, to become king. The following year Godwin's eldest son, Swein, became Earl of the South-West Midlands. (4)

In 1045, Godwin's 20-year-old daughter, Edith, married 42-year-old Edward. Godwin hoped that his daughter would have a son but Edward had taken a vow of celibacy and it soon became clear that the couple would not produce an heir to the throne. Christopher Brooke, the author of The Saxon and Norman Kings (1963), has suggested that this story might have been made up as a part of the legend of royal piety, and as a delicate compliment to a queen who suffered from the common misfortune of failing to bear children." (5)

Harold's older brother, Swein, lost support from his father and the king, when in 1046 he was sent into exile for seducing the abbess of Leominister. At this time Harold became Earl of Eastern England. The area extended across East Anglia, Essex, Huntingdonshire, and Cambridgeshire. During this period that Harold doubtless took as his concubine Edith Swanneck. Such relationships, in spite of increasing pressures from Church leaders were common. Harold and Edith had at least five children. This "Danish marriage", as contemporaries called it, "must have bound Harold closely through ties of kinship and marriage to many Anglo-Scandinavian lords settled in his earldom". (6)

Harold of Wessex

Edward the Confessor became concerned about the growth in power of Earl Godwin and his sons. According to Norman historians, William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers in April 1051, Edward promised William of Normandy that he would be king of the English after his death. David Bates argues that this explains why Earl Godwin, raised an army against the king. The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to Edward and to avoid a civil war, Godwin and his family agreed to go into exile. (7) Tostig moved to mainland Europe and married Judith of Flanders in the autumn of 1051. (8) Harold and Leofwine went to seek help in Ireland. Earl Godwin, Swein and the rest of the family went to live in Bruges. (9)

Edward appointed a Norman, Robert of Jumièges, as Archbishop of Canterbury and Queen Edith was removed from court. Jumièges urged Edward to divorce Edith, but he refused and instead she was sent to a nunnery. (10) Edward also appointed other Normans to official positions. This caused great resentment amongst the English and many of them crossed the Channel to offer Godwin their support. (11)

Godwin and his sons were furious by these developments and in 1052 they returned to England with a mercenary army. Negotiations between the king and the earl were conducted with the help of Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester. Robert left England and was declared an outlaw. Pope Leo IX condemned the appointment of Stigand as the new Archbishop of Canterbury but it was now clear that the Godwin family was back in control. (12)

At a meeting of the King's Council, Godwin cleared himself of the accusations brought against him, and Edward restored him and his sons to land and office, and received Edith once more as his queen. Earl Swein did not return and instead set off from Bruges on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, "to look to the salvation of his soul". John of Worcester says that he walked barefoot all the way and that on the journey home he became ill and died in Lycia on 29th September 1052. (13)

Godwin now forced Edward the Confessor to send his Norman advisers home. Godwin was also given back his family estates and was now the most powerful man in England. Earl Godwin died on 15th April, 1053. Some accounts say he choked on a piece of bread. Others say he was accused of being disloyal to Edward and died during an Ordeal by Cake. Another possibility is that he died from a stroke. His place as the leading Anglo-Saxon in England was taken by his eldest son, Harold. (14)

Death of Edward the Confessor

In 1064 Harold was on board a ship that was wrecked on the coast of Ponthieu. He was captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and imprisoned at Beaurain. William of Normandy, demanded that Count Guy release him into his care. Guy agreed and Harold went with William to Rouen. William later explained what happened: "Edward sent Harold himself to Normandy so that he could swear to me in my presence what his father, Earl Godwin and Earl Leofric (Mercia) and Earl Siward (Northumbria) had sword to me here in my absence. On the journey Harold incurred the danger of being taken prisoner, from which, using force and diplomacy, I rescued him. Through his own hands he made himself my vassal and with his own hand he gave me a firm pledge concerning the kingdom of England." (15)

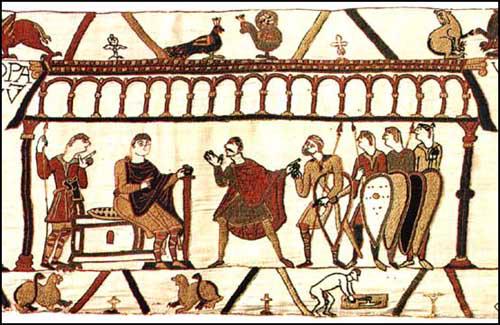

Godwinson (with mustache) in 1064 Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1090)

Harold's brother, Tostig, the Earl of Northumbria, developed a great reputation as a strong military leader. At this time the area was in a lawless state and men were forced to travel in parties of twenty to protect themselves from the attacks of robbers. Tostig imposed new laws and all captured robbers were punished with mutilation or death. This strategy was successful and Northumbria came under his firm control. His biographer, William M. Aird has pointed out: "Tostig is described as a man of courage, endowed with great wisdom and shrewdness of mind. He was favourably compared with his brother Harold, both being distinctly handsome and graceful, similar in strength and bravery." (16)

It is recorded that Tostig "so reduced the number of robbers and cleared the country of them by mutilating or killing them so that any man... could travel at will even alone without fear of attack". (17) It was argued that "a man of property could travel the country safely, even carrying a purse of gold". However, some chroniclers accused him of using his position to enrich himself. (18)

In 1065 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported that Harold's brother, Tostig, the Earl of Northumbria, was guilty of robbing churches, depriving men of their lands and lives, and acting against the law. (19) In October, a group of rebels, supported by Earl Eadwine of Mercia and his brother Morcar, broke into Tostig's residence in York and killed those of his soldiers who did not escape. The rebels then nominated Morcar as their earl. Anyone associated with Tostig's regime was killed. (20)

When the king heard the news he called a meeting of his nobles at Britford. Several made complaints about Tostig's rule claiming that his desire for wealth had made him unduly severe. The king sent Harold to put down the rebellion. Harold disagreed with this policy as he was convinced it would result in a disastrous civil war. At a meeting at Oxford on 28th October, Harold yielded to Edwin's demands. Tostig was banished from the country and Morcar, Harold's brother-in-law, became the new Earl of Northumbria. (21)

In 1065 Edward the Confessor became very ill. Harold claimed that Edward promised him the throne just before he died on 5th January, 1066. (22) The next day there was a meeting of the Witan to decide who would become the next king of England. The Witan was made up of a group of about sixty lords and bishops and they considered the merits of four main candidates: William, Harold, Edgar Etheling and Harald Hardrada. On 6th January 1066, the Witan decided that Harold was to be the next king of England. (23)

King Harold

King Harold was fully aware that both King Hardrada of Norway and William of Normandy might try to take the throne from him. Harold recognised that his country was likely to be invaded both in the south and in the north. He visited York where he had meetings with Earl Eadwine of Mercia and Earl Morcar of Northumbria. He returned to London in time for Easter. (24)

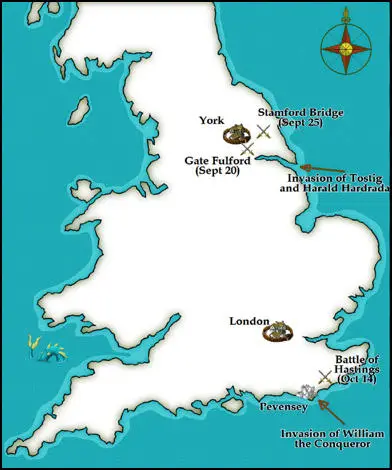

In early 1066, Harold's brother Tostig, with a fleet of sixty ships, attacked the Isle of Wight, occupied Sandwich, and then sailed up the east coast to the mouth of the Humber. The soldiers of Eadwin and Morcar managed to drive him away and Tostig now took refuge with Malcolm III, the King of the Scots in May, 1066. (25)

During this period he also made contact with William of Normandy. According to Frank McLynn, the author of 1066: The Year of The Three Battles (1999), the "steady military build-up did not suit the impatient Tostig, for soon he was off on a mission to find a ruler who would give him more immediate aid". He then went to see Svein Estrithson the king of Denmark. However, he told Tostig that he lacked the resources for an invasion. (26)

Harold fully expected a Norman invasion. It was claimed by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that by June 1066 he had "gathered such a great naval force, and a land force also, as no other king in the land had gathered before." (27) Harold placed his navy and some of the soldiers on the Isle of Wight. The rest of his soldiers were spread along the Sussex and Kent coast. "The object of this arrangement was that in the event of a landing the lookouts on the coast would signal the arrival of the enemy (probably by lighting a beacon) and Harold would then sail from the Isle of Wight with his army to fall upon the invaders". The reason for this is that the prevailing wind, particularly during the summer months, is from the south-west. "It was more than likely that the wind that would carry the invading fleet would be the same upon which Harold would sail, to land behind the invaders or on an adjacent beach." (28)

His soldiers were made up of housecarls and the fyrd. Housecarls were well-trained, full-time soldiers who were paid for their services. The fyrd were working men who were called up to fight for the king in times of danger. All earls had their own housecarls and Harold had a substantial force at his disposal. They were paid mercenaries and were equally adept in land and maritime warfare. (29)

Meanwhile, Tostig was negotiating with King Harald Hardrada about a possible invasion. Eventually the reached an agreement to attack Harold. After appointing his son, Magnus as regent he formed alliances with warriors from Iceland and Ireland. Tostig also convinced Hardrada that Harold was extremely unpopular in the north of England and that people living in this region would join them in their attempt to overthrow the king of England. (30)

Harold waited all summer but the Normans did not arrive. Never before had any of Harold's fyrd been away from their homes for so long. But the men's supplies had run out and they could not be kept away from their homes any longer. Members of the fyrd were also keen to harvest their own fields and so in the first week of September 1066, Harold sent them home. The sailing season was also drawing to a close for the year. Harold therefore decided to arrange for his navy to travel along the Thames to London to enable essential repairs to be carried out. Harold, after a short stay at his home in Bosham, rode to the capital with his housecarls. (31)

William's attack on England had been delayed. To make sure he had enough soldiers to defeat Harold, he asked the men of Poitou, Burgundy, Brittany and Flanders to help. William also arranged for soldiers from Germany, Denmark and Italy to join his army. In exchange for their services, William promised them a share of the land and wealth of England. William also had talks with Pope Alexander II in his campaign to gain the throne of England. These negotiations took all summer. William also had to arrange the building of the ships to take his large army to England. About 700 ships were ready to sail in August but William had to wait a further month for a change in the direction of the wind. (32)

Battle of Stamford Bridge

In the first week of September, 1066, Hardrada's men raided Scarborough and slaughtered most of its inhabitants. Sailing on, the fleet entered the Humber estuary. Morcar, the Earl of Northumbria, and Eadwine, Earl of Mercia, were not willing to engage the enemy and retreated before him up the Ouse, before turning into the inland waters of the Wharfe to Tadcaster. Hardrada anchored at Riccall. After leaving a substantial force to guard the fleet, Hardrada, Tostig and about 6,000 men marched on York. (33)

On 20th September, Morcar and Edwin went into battle with Hardrada and Tostig at Fulford Gate. It has been estimated that the Norwegians had about 6,000 troops and the defenders 5,000. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle "many of the English were slain, drowned or put to flight and the Northmen had possession of the place of slaughter". (34)

Other sources say casualties were high on both sides but it is clear that the invaders had a clear victory. (35) According to one source: "Trying to escape the pincer movement, the English veered away into the marsh, where they foundered in the bog until cut down or sucked into quicksands; those who tried flight on the other side mostly drowned in the Ouse. Soon the marsh and the ditches were clogged with human bodies, to the point where the Norwegians waded in blood and marched over the impacted corpses as if on a solid causeway." (36)

Hardrada then moved onto York, which formally surrendered on 24th September. Hardrada took 150 children hostage from prominent families in Yorkshire as surety for their loyalty. Morcar and Edwin and the remnants of their army escaped into the countryside. The Norwegians now withdrew to Stamford Bridge, a place where several Roman roads met. The bridge would have been quite large by eleventh-century standards. (37)

It has been claimed that a messenger told Harold about the Norwegian victory at Fulford Gate he said that Hardrada had come to conquer all of England. Apparently Harold replied: "I will give him just six feet of English soil; or, since they say he is a tall man, I will give him seven feet." Harold then sent a summons for the men of the fyrd to reassemble, just days after they had been released from their long summer vigil. Having gathered as many of his men as he could he started for the north on about the 19th September. (38)

Harold and his English army had to travel from London to York. The 200 mile (320 km) journey usually took two weeks, or more depending if the roads were passable. (39) The historian, Frank McLynn, the author of 1066: The Year of The Three Battles (1999), has commented "the speed of his advance has always drawn superlatives from historians used to the ponderous pace of medieval warfare, but it may be that a good deal of his force was on horseback and that, as was the custom with Anglo-Saxon armies, they dismounted before fighting." (40)

Peter Rex argues in Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King (2005) that his housecarls were on horseback: "Such mounted infantry could manage twenty-five miles a day. They were also expected to have at least two horses, riding one and allowing the other to proceed unburdened. Harold no doubt could also expect, as king, to commandeer fresh horses along the way. If he did literally ride day and night he could have made Tadcaster in four days, although that would mean without sleep." (41)

On 25th September Harold's army arrived at Stamford Bridge. Harold and twenty of his housecarls rode up to the foot of the bridge on the left bank of the Derwent and had a meeting with Tostig. Harold promised his brother that if he changed sides he would be rewarded with the return of his earldom and one-third of all England. Tostig answered that it would never be said of him that he brought the king of Norway to England only to betray him. He turned on his horse and rode away. (42)

Tostig said they should retreat back to his boats. Hardrada rejected this as being unworthy of a Viking warrior. Aware he was outnumbered he sent a message to his men with his fleet at Ricall to come as soon as possible. He gave orders that his men should stop Harold's army from taking the bridge. "It is said that one particular giant of a man held the bridge single-handed, felling all his attackers with swings from his battleaxe. He was only defeated when he was stabbed from below by a man who was floated down the river under the bridge with a spear." (43)

Once Harold's men had crossed the bridge they engaged the enemy in hand-to-hand combat with swords and axes. The Norsemen were soon being "cut down in their hundreds". The shield-wall was breached and Hardrada was killed by an arrow in the windpipe. His men hesitated about what to do next. Tostig stepped forward and urged them to continue fighting. Tostig was also killed and the rest were forced into the River Derwent, where large numbers drowned. (44)

Harold and his men were left in possession of the battlefield for only a matter of minutes before the rest of the Viking army, fully armed and armoured, appeared on the scene. The Norwegians immediately delivered a ferocious charge which nearly succeeded in breaking the English, but Harold's army stood firm and by the end of the day, those Vikings still alive, under cover of darkness, retreated. Harold chased them back to Riccall. The twenty-year-old Olaf Haraldsson, now in command of the Norwegians, asked for a peace settlement. Harold agreed and allowed the Vikings to return home. The Norwegian losses were considerable. Of the 300 ships that arrived, less than 25 returned to Norway. (45)

Despite the victory, Harold had suffered heavy casualties and his army was severely depleted. However, the battle had shown Harold was a general of great talent. While celebrating his victory at a banquet in York, Harold heard that William of Normandy had landed at Pevensey Bay on 28th September. Harold's brother, Gyrth, offered to lead the army against William, pointing out that as king he should not risk the chance of being killed. "I have taken no oath and owe nothing to Count William". (46)

David Armine Howarth, the author of 1066: the Year of the Conquest (1981) argues that the suggestion was that while Gyrth did battle with William, "Harold should empty the whole of the countryside behind him, block the roads, burn the villages and destroy the food. So, even if Gyrth was beaten, William's army would starve in the wasted countryside as winter closed in and would be forced either to move upon London, where the rest of the English forces would be waiting, or return to their ships." (47)

Harold rejected the advice and immediately assembled the housecarls who had survived the fighting against Hardrada and marched south. Harold travelled at such a pace that many of his troops failed to keep up with him. When Harold arrived in London he waited for the local fyrd to assemble and for the troops of the earls of Mercia and Northumbria to arrive from the north. After five days they had not arrived and so Harold decided to head for the south coast without his northern troops. (48)

Battle of Hastings

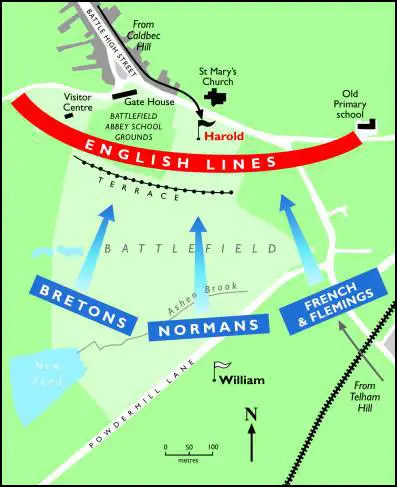

When Harold realised he was unable to take William by surprise, he positioned himself at Senlac Hill near Hastings. Harold selected a spot that was protected on each flank by marshy land. At his rear was a forest. The English housecarls provided a shield wall at the front of Harold's army. They carried large battle-axes and were considered to be the toughest fighters in Europe. The fyrd were placed behind the housecarls. The leaders of the fyrd, the thanes, had swords and javelins but the rest of the men were inexperienced fighters and carried weapons such as iron-studded clubs, scythes, reaping hooks and hay forks.

William of Malmesbury reported: "The courageous leaders mutually prepared for battle, each according to his national custom. The English, as we have heard, passed the night without sleep in drinking and singing, and, in the morning, proceeded without delay towards the enemy; all were on foot, armed with battle-axes... The king himself on foot stood with his brother, near the standard, in order that, while all shared equal danger none might think of retreating... On the other side, the Normans passed the whole night in confessing their sins, and received the Sacrament in the morning. The infantry with bows and arrows, formed the vanguard, while the cavalry, divided into wings, were held back." (49)

There are no accurate figures of the number of soldiers who took part at the Battle of Hastings. Historians have estimated that William had about 5,000 infantry and 3,000 knights while Harold had about 2,000 housecarls and 5,000 members of the fyrd. (50) The Norman historian, William of Poitiers, claims that Harold held the advantage: "The English were greatly helped by the advantage of the high ground... also by their great number, and further, by their weapons which could easily find a way through shields and other defences." (51)

At 9.00 a.m. the Battle of Hastings formally opened with the playing of trumpets. Norman archers then walked up the hill and when they were about a 100 yards away from Harold's army they fired their first batch of arrows. Using their shields, the house-carls were able to block most of this attack. Volley followed volley but the shield wall remained unbroken. At around 10.30 hours, William ordered his archers to retreat.

The Norman army led by William now marched forward in three main groups. On the left were the Breton auxiliaries. On the right were a more miscellaneous body that included men from Poitou, Burgundy, Brittany and Flanders. In the centre was the main Norman contingent "with Duke William himself, relics round his neck, and the papal banner above his head". (52)

The English held firm and eventually the Normans were forced to retreat. Members of the fyrd on the right broke ranks and chased after them. A rumour went round that William was amongst the Norman casualties. Afraid of what this story would do to Norman morale, William pushed back his helmet and rode amongst his troops, shouting that he was still alive. He then ordered his cavalry to attack the English who had left their positions on Senlac Hill. English losses were heavy and very few managed to return to the line. (53)

At about 12.00 p.m. there was a break in the fighting for an hour. This gave both sides a chance to remove the dead and wounded from the battlefield. William, who had originally planned to use his cavalry when the English retreated, decided to change his tactics. At about one in the afternoon he ordered his archers forward. This time he told them to fire higher in the air. The change of direction of the arrows caught the English by surprise. The arrow attack was immediately followed by a cavalry charge. Casualties on both sides were heavy. Those killed included Harold's two brothers, Gyrth and Leofwin. However, the English line held and the Normans were eventually forced to retreat. The fyrd, this time on the left side, chased the Normans down the hill. William ordered his knights to turn and attack the men who had left the line. Once again the English suffered heavy casualties.

William ordered his troops to take another rest. The Normans had lost a quarter of their cavalry. Many horses had been killed and the ones left alive were exhausted. William decided that the knights should dismount and attack on foot. This time all the Normans went into battle together. The archers fired their arrows and at the same time the knights and infantry charged up the hill.

It was now 4.00 p.m. Heavy English casualties from previous attacks meant that the front line was shorter. The Normans could now attack from the side. The few housecarls that were left were forced to form a small circle round the English standard. The Normans attacked again and this time they broke through the shield wall and Harold and most of his housecarls were killed. With their king dead, the fyrd saw no reason to stay and fight, and retreated to the woods behind. The Normans chased the fyrd into the woods but suffered further casualties themselves when they were ambushed by the English.

According to William of Poitiers: "Victory won, the duke returned to the field of battle. He was met with a scene of carnage which he could not regard without pity in spite of the wickedness of the victims. Far and wide the ground was covered with the flower of English nobility and youth. Harold's two brothers were found lying beside him." The next day Harold's mother, Gytha, sent a message to William offering him the weight of the king's body in gold if he would allow her to bury it. He refused, declaring that Harold should be buried on the shore of the land which he sought to guard. (54)

Primary Sources

(1) David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England (1992)

The campaign of Stamford Bridge marks Harold Godwineson as a notable commander. Doubtless, the Norwegian host had suffered heavy losses at Fulford, but it was none the less a formidable army under the leadership of one of the most renowned warriors of the age. Moreover, the force at the disposal of Harold Godwineson had itself been hastily collected, and it had fought under the handicap of several days of forced marches. What, however, stamps the campaign as exceptional is the fact that a commander operating from London was able to achieve surprise against a host whose movements since 20 September had been confined within twenty-five miles of York. The Norwegian king, it is true, had after Fulford been engaged in arranging for the submission of York, in withdrawing his victorious troops to Riccall and then bringing them up again to the road junction at Stamford Bridge, which he probably did not reach until the 24th. Even so, the achievement of Harold Godwineson in coming upon him unawares with an army hastily brought up from the south is very notable. His success was as deserved as it was complete, but it was yet to be seen whether it would be possible for him, after his victory, to return to the south in time to oppose the impending landing of the duke of Normandy.

(2) Arnold Blumberg, Too tired to fight? Harold Godwinson’s Saxon army on the march in 1066 (December 2013)

Many historians postulate that the Saxon army which encountered the Normans at Hastings was already greatly depleted by a forced march from the earlier Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire on 25 September 1066. Certainly King Harold’s Saxon army was having a busy autumn. Near the end of September they had marched the 200 miles (320 km) from London to Yorkshire to repel the invading forces of the Viking ruler Harald Hardrada and his ally, the English king’s brother - turned traitor - Tostig. Then, at the end of the month, the Saxon King received the unpleasant tidings that Duke William had landed on the south coast of Britain. Turning his army about, Harold had no alternative but to march all the way back south in order to meet the new, but not unexpected, Norman threat. By contemporary Western standards this sounds like a tall order, and it is frequently argued that only the elite mounted Saxon housecarls would have been able to make the journey in time.

The question remains as to whether the arduous trek from Yorkshire materially reduced the numerical strength and combat effectiveness of Harold’s army as it raced 270 miles (432 km) for the Sussex coast to confront the Norman invaders. It did not. Why? Because the Saxon army which fought the Normans at Hastings was not the same bloodied Saxon host which triumphed at Stamford Bridge.

The lighting campaign Harold conducted in the north of England against the Norsemen of Harald Hardrada and Tostig was masterful in that it involved speed, surprise and overcoming very difficult terrain. Northern Britain in the mid-eleventh century was divided culturally and politically from the rest of the nation, and was generally left to its own devices. Hard to reach – only a few roads traversed the Humber Estuary and the bogs and swamps of Yorkshire and Cheshire connecting the north and south – the north was an isolated and barren region. The 200 mile (320 km) journey from London to York usually took two weeks, or more depending if the roads were passable.

The fastest way to travel from the south to the north of England was by ship along the country’s east coast. Unfortunately for Harold, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a few days before he heard of the Viking incursion in the north, he had disbanded his army which he had assembled some months before in anticipation of an appearance by the hostile William Duke of Normandy. The army had to be broken up, since the customary 60 day enlistment period for most of his soldiers had come to an end. It was also becoming more and more difficult to keep the army and navy intact due to the problem of supplying them. On 8 September, Harold got wind of Hardrada’s northern incursion. Prior to that alarming news the Saxon fleet had been sent to London, but, as reported by theAnglo-Saxon Chronicle, it had lost many vessels as it made its way to the city around the south coast. The damage to his fleet may have been the prime reason the king did not sail for the north instead of making the arduous overland journey on foot. Given favorable wind and tides a sea voyage would have taken about three days. Thus, Harold could have avoided much of the stress and strain on the troops making the move north, as well as the burdensome supply requirements (i.e. passable roads, wheeled transport and draught animals) needed to support such a march to the north.

Regardless, the Saxons, after leaving London in the middle of September, arrived in Yorkshire, near Tadcaster, on 24 September. They had covered 200 grueling miles in a little over a week, making an impressive 22 to 25 miles (35-40 km) a day. The army’s rapid progress surprised the unsuspecting Norsemen, resulting in their complete defeat at the savage Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September.

Having successfully disposed of one menace to his throne, sometime between 29 September and 1 October Harold was notified that the long awaited invasion of Saxon England by William of Normandy had taken place. He now had no choice but to return to the south to deal with this new threat.

(3) John Grehan and Martin Mace, The Battle of Hastings: The Uncomfortable Truth (2012)

With a fleet drawn from harbours along the south coast Harold took up a position on the Isle of Wight with the bulk of his army. The remainder of his forces were spread along the coast. The object of this arrangement was that in the event of a landing the lookouts on the coast would signal the arrival of the enemy (probably by lighting a beacon) and Harold would then sail from the Isle of Wight with his army to fall upon the invaders. The reason for this is that the prevailing wind, particularly during the summer months, is from the south-west. Indeed, it was more than likely that the wind that would carry the invading fleet would be the same upon which Harold would sail, to land behind the invaders or on an adjacent beach.

(4) Winston Churchill, The Island Race (1964)

Harold of England was faced with a double invasion from the North-East and from the South. In September 1066 he heard that a Norwegian fleet, with Hardrada and Tostig on board, had sailed up the Humber, beaten the local levies under Earls Edwin and Morcar, and encamped near York at Stamford Bridge. He now showed the fighting qualities he possessed. Within five days of the defeat of Edwin and Morcar, Harold reached York, and the same day marched to confront the Norwegian army ten miles from the city.

(5) Frank McLynn, 1066: The Year of The Three Battles (1999)

Taking his brother Gyrth with him, and with his housecarls and such other troops as he could spare from the distance of the south. Harold marched north in seven divisions, pressing volunteers as he went. The speed of his advance has always drawn superlatives from historians used to the ponderous pace of medieval warfare, but it may be that a good deal of his force was on horseback and that, as was the custom with Anglo-Saxon armies, they dismounted before fighting.

(6) Peter Rex, Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King (2005)

Such mounted infantry could manage twenty-five miles a day. They were also expected to have at least two horses, riding one and allowing the other to proceed unburdened. Harold no doubt could also expect, as king, to commandeer fresh horses along the way. If he did literally ride day and night he could have made Tadcaster in four days, although that would mean without sleep.

(7) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, C Version, entry for 1066.

There was one of the Norwegians there who withstood the English host so they could not cross the bridge nor win victory. Then an Englishman shot an arrow, but it was no use, and then another came under the bridge and stabbed him under the corselet. Then Harold, king of the English, came over the bridge and his host with him, and there killed large numbers of both Norwegians and Flemings, and Harold let the king's son Hetmundus go home to Noway with all ships.

(8) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, D Version, entry for 1066.

The Norwegians who survived took flight; and the English attacked them fiercely as they pursued them until some got to the ships. Some were drowned, and some burned, and some destroyed in various ways so that few survived and the English remained in command of the field. The king gave quarter to Olaf, son of the Norse king and all those who survived on the ships, and they went up to our king and swore oaths that they would always keep peace and friendship with this country; and the king let them go home with twenty-four ships.

(9) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, D Version (1066)

Then came William duke of Normandy into Pevensey... This was then made known to King Harold, and he then gathered a great force, and came to meet him at the estuary of Appledore; and William came against him unawares before his people were assembled. But the king nevertheless strenuously fought against him with those men who would follow him; and there was great slaughter made on either hand. There was slain King Harold and Leofwine the earl... and the Frenchman had possession of the place of carnage, all as God granted them for the people's sins.

(10) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Version D (1066)

Then came William duke of Normandy into Pevensey... This was then made known to King Harold, and he then gathered a great force, and came to meet him at the estuary of Appledore; and William came against him unawares before his people were assembled... King Harold was killed... and the French were masters of the field... God granted it to them because of the sins of the people.

Student Activities

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)