Battle of Hastings

In 1065 Edward the Confessor became very ill. Harold of Wessex claimed that Edward promised him the throne just before he died on 5th January, 1066. The next day there was a meeting of the Witan to decide who would become the next king of England. The Witan was made up of a group of about sixty lords and bishops and they considered the merits of four main candidates: Harold, William of Normandy, Edgar Etheling and Harald Hardrada. On 6th January 1066, the Witan decided that Harold was to be the next king of England. (1)

King Harold was fully aware that both King Hardrada of Norway and William of Normandy might try to take the throne from him. Harold believed that the Normans posed the main danger and he positioned his troops on the south coast of England. His soldiers were made up of housecarls and the fyrd. Housecarls were well-trained, full-time soldiers who were paid for their services. The fyrd were working men who were called up to fight for the king in times of danger.

Harold waited all summer but the Normans did not arrive. Never before had any of Harold's fyrd been away from their homes for so long. But the men's supplies had run out and they could not be kept away from their homes any longer. Members of the fyrd were also keen to harvest their own fields and so in September Harold sent them home. Harold also sent his navy back to London. (2)

William of Normandy

William's attack on England had been delayed. To make sure he had enough soldiers to defeat Harold, he asked the men of Poitou, Burgundy, Brittany and Flanders to help. William also arranged for soldiers from Germany, Denmark and Italy to join his army. In exchange for their services, William promised them a share of the land and wealth of England. William also had talks with Pope Alexander II in his campaign to gain the throne of England. These negotiations took all summer. William also had to arrange the building of the ships to take his large army to England. About 700 ships were ready to sail in August but William had to wait a further month for a change in the direction of the wind. (3)

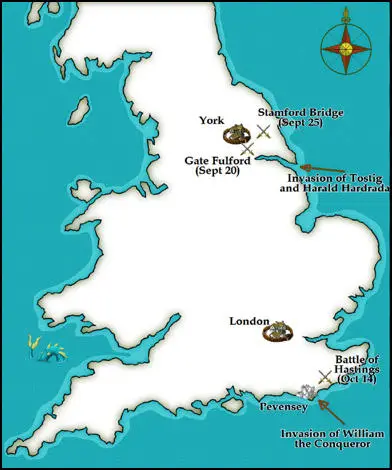

In early September Harold heard that King Hardrada of Norway had invaded northern England. The messenger told Harold that Hardrada had come to conquer all of England. It is said that Harold replied: "I will give him just six feet of English soil; or, since they say he is a tall man, I will give him seven feet." With Hardrada was Harold's brother, Tostig, and 300 ships. Harold and what was left of his army headed north. Hardrada and his men entered the Humber and on 20th September defeated Morcar's army at Gate Fulford. Four days later the invaders took York. On the way Harold heard that the earls of Mercia and Northumbria had been defeated and were considering changing sides.

The English army marched 190 miles from London to York in just four days. On 24th September Harold's army arrived at Tadcaster. The following day he took Tostig and Hardrada by surprise at a place called Stamford Bridge. It was a hot day and the Norwegians had taken off their byrnies (leather jerkins with sewn-on metal rings). Harold and his English troops devastated the Norwegians. Both Hardrada and Tostig were killed. The Norwegian losses were considerable. Of the 300 ships that arrived, less than 25 returned to Norway. (4)

While celebrating his victory at a banquet in York, Harold heard that William of Normandy had landed at Pevensey Bay on 28th September. Harold's brother, Gyrth, offered to lead the army against William, pointing out that as king he should not risk the chance of being killed. "I have taken no oath and owe nothing to Count William". (5)

David Armine Howarth, the author of 1066: the Year of the Conquest (1981) argues that the suggestion was that while Gyrth did battle with William, "Harold should empty the whole of the countryside behind him, block the roads, burn the villages and destroy the food. So, even if Gyrth was beaten, William's army would starve in the wasted countryside as winter closed in and would be forced either to move upon London, where the rest of the English forces would be waiting, or return to their ships." (6)

Harold rejected the advice and immediately assembled the housecarls who had survived the fighting against Hardrada and marched south. Harold travelled at such a pace that many of his troops failed to keep up with him. When Harold arrived in London he waited for the local fyrd to assemble and for the troops of the earls of Mercia and Northumbria to arrive from the north. After five days they had not arrived and so Harold decided to head for the south coast without his northern troops. (7)

Battle of Hastings

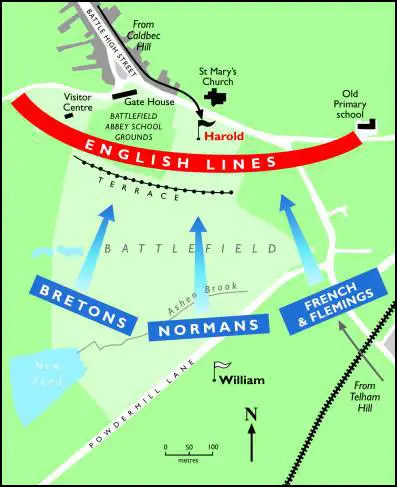

Harold of Wessex realised he was unable to take William by surprise. He therefore decided to position himself at Senlac Hill near Hastings. Harold selected a spot that was protected on each flank by marshy land. At his rear was a forest. The English housecarls provided a shield wall at the front of Harold's army. They carried large battle-axes and were considered to be the toughest fighters in Europe. The fyrd were placed behind the housecarls. The leaders of the fyrd, the thanes, had swords and javelins but the rest of the men were inexperienced fighters and carried weapons such as iron-studded clubs, scythes, reaping hooks and hay forks.

William of Malmesbury reported: "The courageous leaders mutually prepared for battle, each according to his national custom. The English, as we have heard, passed the night without sleep in drinking and singing, and, in the morning, proceeded without delay towards the enemy; all were on foot, armed with battle-axes... The king himself on foot stood with his brother, near the standard, in order that, while all shared equal danger none might think of retreating... On the other side, the Normans passed the whole night in confessing their sins, and received the Sacrament in the morning. The infantry with bows and arrows, formed the vanguard, while the cavalry, divided into wings, were held back." (8)

There are no accurate figures of the number of soldiers who took part at the Battle of Hastings. Historians have estimated that William had about 5,000 infantry and 3,000 knights while Harold had about 2,000 housecarls and 5,000 members of the fyrd. (9) The Norman historian, William of Poitiers, claims that Harold held the advantage: "The English were greatly helped by the advantage of the high ground... also by their great number, and further, by their weapons which could easily find a way through shields and other defences." (10)

At 9.00 a.m. the Battle of Hastings formally opened with the playing of trumpets. Norman archers then walked up the hill and when they were about a 100 yards away from Harold's army they fired their first batch of arrows. Using their shields, the house-carls were able to block most of this attack. Volley followed volley but the shield wall remained unbroken. At around 10.30 hours, William ordered his archers to retreat.

The Norman army led by William now marched forward in three main groups. On the left were the Breton auxiliaries. On the right were a more miscellaneous body that included men from Poitou, Burgundy, Brittany and Flanders. In the centre was the main Norman contingent "with Duke William himself, relics round his neck, and the papal banner above his head". (11)

The English held firm and eventually the Normans were forced to retreat. Members of the fyrd on the right broke ranks and chased after them. A rumour went round that William was amongst the Norman casualties. Afraid of what this story would do to Norman morale, William pushed back his helmet and rode amongst his troops, shouting that he was still alive. He then ordered his cavalry to attack the English who had left their positions on Senlac Hill. English losses were heavy and very few managed to return to the line. (12)

At about 12.00 p.m. there was a break in the fighting for an hour. This gave both sides a chance to remove the dead and wounded from the battlefield. William, who had originally planned to use his cavalry when the English retreated, decided to change his tactics. At about one in the afternoon he ordered his archers forward. This time he told them to fire higher in the air. The change of direction of the arrows caught the English by surprise. The arrow attack was immediately followed by a cavalry charge. Casualties on both sides were heavy. Those killed included Harold's two brothers, Gyrth and Leofwin. However, the English line held and the Normans were eventually forced to retreat. The fyrd, this time on the left side, chased the Normans down the hill. William ordered his knights to turn and attack the men who had left the line. Once again the English suffered heavy casualties.

William of Normandy ordered his troops to take another rest. The Normans had lost a quarter of their cavalry. Many horses had been killed and the ones left alive were exhausted. William decided that the knights should dismount and attack on foot. This time all the Normans went into battle together. The archers fired their arrows and at the same time the knights and infantry charged up the hill.

It was now 4.00 p.m. Heavy English casualties from previous attacks meant that the front line was shorter. The Normans could now attack from the side. The few housecarls that were left were forced to form a small circle round the English standard. The Normans attacked again and this time they broke through the shield wall and Harold and most of his housecarls were killed. With their king dead, the fyrd saw no reason to stay and fight, and retreated to the woods behind. The Normans chased the fyrd into the woods but suffered further casualties themselves when they were ambushed by the English.

According to William of Poitiers: "Victory won, the duke returned to the field of battle. He was met with a scene of carnage which he could not regard without pity in spite of the wickedness of the victims. Far and wide the ground was covered with the flower of English nobility and youth. Harold's two brothers were found lying beside him." The next day Harold's mother, Gytha, sent a message to William offering him the weight of the king's body in gold if he would allow her to bury it. He refused, declaring that Harold should be buried on the shore of the land which he sought to guard. (13)

Primary Sources

(1) Message sent by William of Normandy just before the Battle of Hastings took place (quoted by William of Poitiers in Deeds of the Dukes of the Normans (c. 1070)

I have no desire to protect myself behind any rampart... With the aid of God I would not hesitate to oppose (the English) with my own men even if I had only ten thousand of these instead of sixty thousand I now command.

(2) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, D Version, entry for 1066.

Then came William duke of Normandy into Pevensey... This was then made known to King Harold, and he then gathered a great force, and came to meet him at the estuary of Appledore; and William came against him unawares before his people were assembled. But the king nevertheless strenuously fought against him with those men who would follow him; and there was great slaughter made on either hand. There was slain King Harold and Leofwine the earl... and the Frenchman had possession of the place of carnage, all as God granted them for the people's sins.

(3) William of Malmesbury, The Deeds of the Kings of the English (c. 1140)

The courageous leaders mutually prepared for battle, each according to his national custom. The English, as we have heard, passed the night without sleep in drinking and singing, and, in the morning, proceeded without delay towards the enemy; all were on foot, armed with battle-axes... The king himself on foot stood with his brother, near the standard, in order that, while all shared equal danger none might think of retreating... On the other side, the Normans passed the whole night in confessing their sins, and received the Sacrament in the morning. The infantry with bows and arrows, formed the vanguard, while the cavalry, divided into wings, were held back.

(The English) few in number and brave in the extreme... they fought with ardour neither giving ground, for great part of the day. Finding this, William gave a signal to his party, that, by a feigned flight, they should retreat. Through this device the close body of the English, opening for the purpose of cutting down the straggling enemy brought upon itself swift destruction; for the Normans, facing about, attacked them thus disordered, and compelled them to fly.

Harold, not merely content with the duty of a general in exhorting others would strike the enemy when coming to close quarters, so that none would approach him with impunity; for immediately the same blow levelled both horse and rider first one party conquering, and then the other, prevailed as long as the life of Harold continued; but when he fell, his brain pierced by an arrow... One of the soldiers with a sword gashed his thigh as he lay prostrate; for which shameful and cowardly action he was branded with ignominy by William and dismissed.

(4) William of Poitiers, The Deeds of William, Duke of the Normans (c. 1071)

Duke William advanced with the banner which the Pope had sent him. There were two bishops from Normandy, together with many clergy and a number of monks. The clergy led prayers before the battle.

The vast forces of English had come from all regions. Harold took up position on higher ground, on a hill by a forest through which they had just come. They abandoned their horses and drew themselves up in close order.

The duke placed his infantry in front armed with bows and crossbows and behind them other infantry more heavily armed with mail tunics; in the rear came the mounted knights.

The terrible sound of trumpets on both sides announced the opening of the battle. The Norman foot soldiers... challenged the English, raining wounds and death upon them with their missiles. The English... threw spears and weapons of every kind, murderous axes and stones tied to sticks.

The English were greatly helped by the advantage of the high ground... also by their great number, and further, by their weapons which could easily find a way through shields and other defences... Terrified by this ferocity, the Norman foot soldiers began to retreat... The duke galloped up in front of them, shouting and brandishing his lance. Removing his helmet to bare his head, he cried: "Look at me. I am alive, and, by God's help, I shall win. What madness puts you to flight? Where do you think you can go? You are deserting victory and everlasting honour; you are running away to destruction and everlasting shame. And by flight not one of you will avoid death." The duke was the first to charge forward, sword flashing, cutting down the English who deserved death as rebels to him, their king.

The English were so densely massed that the dead could scarcely fall. However, breaches were cut in several places by the swords of the Norman knights... The Normans realising that they could not overcome an enemy so numerous and standing so firm without great loss to themselves, retreated, deliberately feigning flight. The English poured scorn upon our men and boasted that they would be destroyed then and there. As before, thousands of them were bold enough to launch themselves as if on wings after those they thought to be fleeing.

The Normans, suddenly wheeling their horses about, cut them off, surrounding them, and slew them on all sides, leaving not one alive.

Twice they used the same strategy to the same effect, and then attacked more furiously than ever... The English began to weaken.

William was a noble general, inspiring courage, sharing danger, more often commanding men to follow than urging them on from the rear... The enemy lost heart at the mere sight of this marvellous and terrible knight. Three horses were killed under him. Three times he leapt to his feet. Shields, helmets, hauberks were cut by his furious and flashing blade, while yet other assailants were clouted by his own shield. His knights were astonished to see him a foot-soldier, and many, stricken with wounds, were given new heart.

As the day went on the English army realised they could no longer stand against the Normans. They knew they were reduced by heavy loses; that the king himself, with his brothers and many other magnates, had fallen. Those who still stood were almost drained of strength...

They saw the Normans threatening them more keenly than in the beginning, as if they found new strength in the flight; they saw the fury of the duke who spared no one who resisted him; they saw that courage which could only find rest in victory. They therefore turned to fight and made off as soon as they got the chance, some on stolen horses, many on foot... The Normans pursued them keenly, slaughtering the guilty fugitives and bringing matters to a fitting end.

Victory won, the duke returned to the field of battle. He was met with a scene of carnage which he could not regard without pity in spite of the wickedness of the victims. Far and wide the ground was covered with the flower of English nobility and youth. Harold's two brothers were found lying beside him...

Harold's mother offered for her beloved son's body his weight in gold. William believed Harold to be unworthy of burial as his mother wished. He gave the body to William Malet, and not to Harold's mother.

Student Activities

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)