The Battle of Stamford Bridge

On Edward the Confessor became concerned about the growth in power of Godwin, the Earl of Wessex and his sons. According to Norman historians, William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers in April 1051, Edward promised William of Normandy that he would be king of the English after his death. David Bates argues that this explains why Earl Godwin, raised an army against the king. The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to Edward and to avoid a civil war, Godwin and his family agreed to go into exile. (1) Tostig moved to mainland Europe and married Judith of Flanders in the autumn of 1051. (2) Harold and Leofwine went to seek help in Ireland. Earl Godwin, Swein and the rest of the family went to live in Bruges. (3)

Edward appointed a Norman, Robert of Jumièges, as Archbishop of Canterbury and Queen Edith was removed from court. Jumièges urged Edward to divorce Edith, but he refused and instead she was sent to a nunnery. (4) Edward also appointed other Normans to official positions. This caused great resentment amongst the English and many of them crossed the Channel to offer Godwin their support. (5)

Godwin and his sons were furious by these developments and in 1052 they returned to England with a mercenary army. Edward was unable to raise significant forces to stop the invasion. Most of the men in Kent, Surrey and Sussex joined the rebellion. Godwin's large fleet moved round the coast and recruited men in Hastings, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich. He then sailed up the Thames and soon gained the support of Londoners. (6)

Negotiations between the king and the earl were conducted with the help of Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester. Robert left England and was declared an outlaw. Pope Leo IX condemned the appointment of Stigand as the new Archbishop of Canterbury but it was now clear that the Godwin family was back in control. (7)

At a meeting of the King's Council, Godwin cleared himself of the accusations brought against him, and Edward restored him and his sons to land and office, and received Edith once more as his queen. Earl Swein did not return and instead set off from Bruges on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, "to look to the salvation of his soul". John of Worcester says that he walked barefoot all the way and that on the journey home he became ill and died in Lycia on 29th September 1052. (8)

Godwin now forced Edward the Confessor to send his Norman advisers home. Godwin was also given back his family estates and was now the most powerful man in England. Earl Godwin died on 15th April, 1053. Some accounts say he choked on a piece of bread. Others say he was accused of being disloyal to Edward and died during an Ordeal by Cake. Another possibility is that he died from a stroke. His place as the leading Anglo-Saxon in England was taken by his eldest son, Harold. (9)

In 1064 Harold was on board a ship that was wrecked on the coast of Ponthieu. He was captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and imprisoned at Beaurain. William of Normandy, demanded that Count Guy release him into his care. Guy agreed and Harold went with William to Rouen. William later explained what happened: "Edward sent Harold himself to Normandy so that he could swear to me in my presence what his father, Earl Godwin and Earl Leofric (Mercia) and Earl Siward (Northumbria) had sword to me here in my absence. On the journey Harold incurred the danger of being taken prisoner, from which, using force and diplomacy, I rescued him. Through his own hands he made himself my vassal and with his own hand he gave me a firm pledge concerning the kingdom of England." (10)

Godwinson (with mustache) in 1064 Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1090)

In 1065 Edward the Confessor became very ill. Harold claimed that Edward promised him the throne just before he died on 5th January, 1066. (11) The next day there was a meeting of the Witan to decide who would become the next king of England. The Witan was made up of a group of about sixty lords and bishops and they considered the merits of four main candidates: William, Harold, Edgar Etheling and Harald Hardrada. On 6th January 1066, the Witan decided that Harold was to be the next king of England. (12)

King Harold was fully aware that both King Hardrada of Norway and William of Normandy might try to take the throne from him. Harold believed that the Normans posed the main danger and he positioned his troops on the south coast of England. His soldiers were made up of housecarls and the fyrd. Housecarls were well-trained, full-time soldiers who were paid for their services. The fyrd were working men who were called up to fight for the king in times of danger.

Harold waited all summer but the Normans did not arrive. Never before had any of Harold's fyrd been away from their homes for so long. But the men's supplies had run out and they could not be kept away from their homes any longer. Members of the fyrd were also keen to harvest their own fields and so in September Harold sent them home. Harold also sent his navy back to London. (13)

William's attack on England had been delayed. To make sure he had enough soldiers to defeat Harold, he asked the men of Poitou, Burgundy, Brittany and Flanders to help. William also arranged for soldiers from Germany, Denmark and Italy to join his army. In exchange for their services, William promised them a share of the land and wealth of England. William also had talks with Pope Alexander II in his campaign to gain the throne of England. These negotiations took all summer. William also had to arrange the building of the ships to take his large army to England. About 700 ships were ready to sail in August but William had to wait a further month for a change in the direction of the wind. (14)

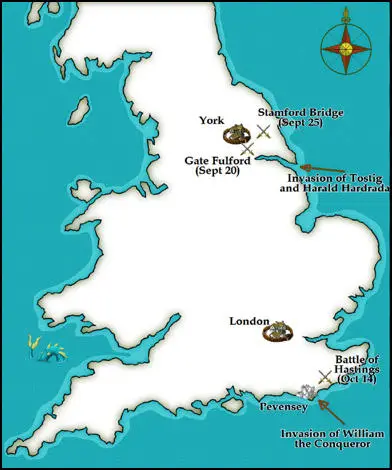

In early September Harold heard that King Hardrada of Norway had invaded northern England. The messenger told Harold that Hardrada had come to conquer all of England. It is said that Harold replied: "I will give him just six feet of English soil; or, since they say he is a tall man, I will give him seven feet." With Hardrada was Harold's brother, Tostig, and 300 ships. Harold and what was left of his army headed north. Hardrada and his men entered the Humber and on 20th September defeated Morcar's army at Gate Fulford. Four days later the invaders took York. On the way Harold heard that the earls of Mercia and Northumbria had been defeated and were considering changing sides.

The English army marched 190 miles from London to York in just four days. (15) Frank McLynn, the author of 1066: The Year of The Three Battles (1999), has commented "the speed of his advance has always drawn superlatives from historians used to the ponderous pace of medieval warfare, but it may be that a good deal of his force was on horseback and that, as was the custom with Anglo-Saxon armies, they dismounted before fighting." (16)

Peter Rex argues in Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King (2005) that his housecarls were on horseback: "Such mounted infantry could manage twenty-five miles a day. They were also expected to have at least two horses, riding one and allowing the other to proceed unburdened. Harold no doubt could also expect, as king, to commandeer fresh horses along the way. If he did literally ride day and night he could have made Tadcaster in four days, although that would mean without sleep." (17)

On 24th September Harold's army arrived at Tadcaster. The following day he took Tostig and Hardrada by surprise at a place called Stamford Bridge. It was a hot day and the Norwegians had taken off their byrnies (leather jerkins with sewn-on metal rings). Harold and his English troops devastated the Norwegians. Both Hardrada and Tostig were killed. The Norwegian losses were considerable. Of the 300 ships that arrived, less than 25 returned to Norway. (18)

While celebrating his victory at a banquet in York, Harold heard that William of Normandy had landed at Pevensey Bay on 28th September. Harold's brother, Gyrth, offered to lead the army against William, pointing out that as king he should not risk the chance of being killed. "I have taken no oath and owe nothing to Count William". (19)

David Armine Howarth, the author of 1066: the Year of the Conquest (1981) argues that the suggestion was that while Gyrth did battle with William, "Harold should empty the whole of the countryside behind him, block the roads, burn the villages and destroy the food. So, even if Gyrth was beaten, William's army would starve in the wasted countryside as winter closed in and would be forced either to move upon London, where the rest of the English forces would be waiting, or return to their ships." (20)

Harold rejected the advice and immediately assembled the housecarls who had survived the fighting against Hardrada and marched south. Harold travelled at such a pace that many of his troops failed to keep up with him. When Harold arrived in London he waited for the local fyrd to assemble and for the troops of the earls of Mercia and Northumbria to arrive from the north. After five days they had not arrived and so Harold decided to head for the south coast without his northern troops. (21)

Primary Sources

(1) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, C Version, entry for 1066.

There was one of the Norwegians there who withstood the English host so they could not cross the bridge nor win victory. Then an Englishman shot an arrow, but it was no use, and then another came under the bridge and stabbed him under the corselet. Then Harold, king of the English, came over the bridge and his host with him, and there killed large numbers of both Norwegians and Flemings, and Harold let the king's son Hetmundus go home to Norway with all ships.

(2) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, D Version, entry for 1066.

The Norwegians who survived took flight; and the English attacked them fiercely as they pursued them until some got to the ships. Some were drowned, and some burned, and some destroyed in various ways so that few survived and the English remained in command of the field. The king gave quarter to Olaf, son of the Norse king and all those who survived on the ships, and they went up to our king and swore oaths that they would always keep peace and friendship with this country; and the king let them go home with twenty-four ships.

(3) Florence of Worcester was a monk who wrote an account of the Battle of Stamford Bridge in about 1125.

Harold, king of the English, permitted Olaf, the son of the Norwegian king, to return home unmolested with twenty ships and the survivors, but only after they had sworn oaths of submission and had given hostages.

(4) David Armine Howarth, 1066: the Year of the Conquest (1981)

Harold should empty the whole of the countryside behind him, block the roads, burn the villages and destroy the food. So, even if Gyrth was beaten, William's army would starve in the wasted countryside as winter closed in and would be forced either to move upon London, where the rest of the English forces would be waiting, or return to their ships.

(5) Frank McLynn, 1066: The Year of The Three Battles (1999)

The speed of his advance has always drawn superlatives from historians used to the ponderous pace of medieval warfare, but it may be that a good deal of his force was on horseback and that, as was the custom with Anglo-Saxon armies, they dismounted before fighting.

(6) Peter Rex, Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King (2005)

Such mounted infantry could manage twenty-five miles a day. They were also expected to have at least two horses, riding one and allowing the other to proceed unburdened. Harold no doubt could also expect, as king, to commandeer fresh horses along the way. If he did literally ride day and night he could have made Tadcaster in four days, although that would mean without sleep.

Student Activities

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Wandering Minstrels in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

Henry II: An Assessment (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Richard the Lionheart (Answer Commentary)

Medieval and Modern Historians on King John (Answer Commentary)

King John and the Magna Carta (Answer Commentary)

Medieval Historians and John Ball (Answer Commentary)

The Peasants' Revolt (Answer Commentary)

Death of Wat Tyler (Answer Commentary)