Apache

Apaches were nomadic tribes living in Arizona and New Mexico. The name comes from the Zuni word apachu (enemy). They travelled in small raiding bands or clans and lived in brush shelters called wickyups. There were six main tribal divisions: Jicarilla, Mescalero, Chircahua, Mimbrenos, San Carlos and Coyotero. There was little tribal solidarity and they did most of their fighting in small groups.

On 27th January, 1861, a group of Apaches led by Chatto stole cattle and kidnapped a boy from a Sonoita Valley ranch. Second Lieutenant George Bascom was sent out with 54 soldiers to recover the boy. Cochise met Bascom and told him that he would try to recover the boy. Bascom rejected the offer and instead tried to take Cochise hostage. When he tried to flee he was shot at by the soldiers. The wounded Cochise now gave orders for the execution of four white men being held in captivity. In retaliation six Apaches were hanged. Open warfare now broke out and during the next 60 days 150 white people were killed and five stage stations destroyed.

Mangas Coloradas and Cochise killed five people during an attack on a stage at Stein's Peak, New Mexico. In July, 1861 a war party murdered six white people travelling on a stage coach at Cooke's Canyon. On 14th July, 1862 Mangas Coloradas, Juh, Victorio, Geronimo and Cochise took part in the attack at Apache Pass. The Apaches also attacked stage coaches and in 1869 killed a Texas cowboy and stole 250 cattle. Cochise and his men were pursued but after a fight near Fort Bowie the soldiers were forced to retreat.

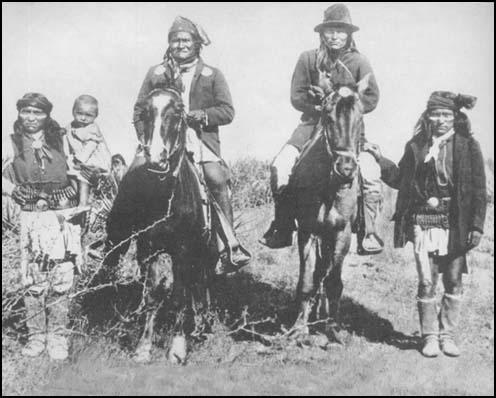

Geronimo, the leader of the Chiricahua in Arizona, went on the warpath when in 1876 the American government ordered them from their mountain homeland to the San Carlos Reservation. Geronimo refused to go and over the next few years he led a small band of warriors that raided settlements in Arizona. Geronimo also attacked American troops in the Whetstone Mountains, Arizona, on 9th January, 1877. This was followed by a rare defeat in the Leitendorf Mountains.

Geronimo was captured when entering the Ojo Caliente Reservation in New Mexico. Geronimo was eventually released and by April 1878 he was leading war parties in Mexico. The following year Geronimo surrendered and settled on the San Carlos Reservation.

On 21st August, 1879, Victorio took his people to the Black Range mountains. He fought off an attempt to arrest him by Major Albert Morrow. He then moved east and ambushed Mexican militia killing around 30 men. With the help of Apache scouts the army traced him in the Black Mountains. However, he once again escaped and by August 1880 was launching further attacks in West Texas.

On 15th October, 1880, Lieutenant Colonel Joaquin Terrazas finally ambushed Victorio and his men in the Tres Castillos Mountains in Chihuahua. Victorio and 77 other Apaches were killed in the fighting.

In 1881 Juh and Geronimo and their people left the reservation and headed for the Sierra Madre. In 1882 they carried out their most ambitious raid of all when they attacked San Carlos.

After the death of Juh, Geronimo became the leader of the Apache warriors still resisting white settlement. He continued to carry out raids until he took part in peace talks with General George Crook. Crook was criticized for the way he was dealing with the situation and as a result he asked to be relieved of his command.

General Nelson Miles replaced Crook and attempted to defeat Geronimo by military means. This strategy was also unsuccessful and eventually he resorting to Crook's strategy of offering a negotiated deal. In September 1886 Geronimo signed a peace treaty with Miles and the last of the Indian Wars was over.

Primary Sources

(1) Nelson Miles, Personal Recollections and Observations (1896)

The Apaches believed themselves to be the first and superior race. In some respects they were superior. They excelled in activity, cunning, endurance, and cruelty. The stories of the feats of men running a hundred miles in a day come down to us from the days of Coronado and from the old officers of the army who were formerly stationed in that country. Their lung power enabled them to start at the base of a mountain and run to the summit without stopping. An account of their atrocities and raids would fill a volume. Once numerous and powerful, by almost constant warfare they have become greatly reduced in numbers.

They had an abundance of arms and ammunition, for they not only raided and plundered stores, ranches, and freight trains, but they could completely conceal themselves with grass, brush, and feathers, and lie in ambush in ravines near the trail, so that the prospector, miner, ranchman, or traveler would never observe them until he felt the deadly bullet from their rifles. In this way they kept themselves well supplied with whatever they required. Their endurance was most extraordinary. When hard pushed and driven to the higher peaks of the mountains they could subsist on field-mice and the juice of the giant cactus. They would go to their reservations and agencies for a time to replenish their wants and recruit their members; then return to the warpath. Their docility and meekness while peaceable was only excelled by their ferocity and cruelty when at war.

For a few weeks or months they would be "horny-handed sons of toil," and then for an equal time they would be red-handed assassins and marauders. They were at times composed of the Yumas, Mojaves, White Mountains, and Chiricahuas, the last named being the dominant and most warlike tribe. Theyinhabited the most rugged and inaccessible regions of the Rocky and Sierra Madre mountains. When pursued they would steal horses in one valley, ride until they exhausted them, and then destroy or abandon them, travel on foot over the mountains, descend and raid another valley, and continue this course until they felt themselves free from their pursuers. They recognized no authority or force superior to their own will.

Led by Mangus-Colorado, Cochise, Victorio, and later by Geronimo, Natchez, Chatto, and Mangus, they kept the whole country in a state of terror.

(2) Pat Garrett, The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid (1882)

The Mescalero Apache Indians, from the Fort Stanton, New Mexico, Reservation, used to make frequent raids into Old Mexico, and often attacked emigrants along the Rio Grande. On one occasion, a party from Texas, consisting of three men and their families, on their way to Arizona, came across Billy and Jess. in the vicinity of the Rio Miembres. They took dinner together and the Texans volunteered much advice to the two unsophisticated boys, representing the danger they braved by travelling unprotected through an Indian country, and proposing that they should pursue their journey in company. They represented themselves as old and experienced Indian fighters, who had, in Texas, scored their hundreds of dead Comanches, Kickapoos, and Lipans. The boys declined awaiting the slow motion of ox wagons, and after dinner, rode on.

(3) Captain John G. Bourke served under General George Crook. In 1891 he wrote about an event that took place on 28th December, 1872.

We moved onward again for three or four hours until we reached a small grassy glade, where we discovered fifteen Pima ponies, which must have been driven up the mountain by Apache raiders that very night; the sweat was hardly crusted on their flanks, their hoofs were banged against the rocks, and their knees were full of the thorns of the cholla cactus, against which they had been driven in the dark. There was no moon, but the glint of stars gave enough light to show that we were in a country filled with huge rocks and adapted most admirably for defense. There in front, almost within touch of the hand, that line of blackness blacker than all the other blackness about us was the canyon of the Salt River. We looked at it well, since it might be our grave in an hour, for we were now within rifle shot of our quarry.

Nantaje (an Apache scout) now asked that a dozen picked men be sent forward with him, to climb down the face of the precipice and get into place in front of the cave in order to open the attack; immediately behind them should come fifty more, who should make no delay in their advance; a strong detachment should hold the edge of the precipice to prevent any of the hostiles from getting above them and killing our people with their rifles. The rest of our force could come down more at leisure, if the movement of the first two detachments secured the key of the field; if not, they could cover the retreat of the survivors up the face of the escarpment.

Lieutenant William J. Ross, of the 2Ist Infantry, was assigned to lead the first detachment, which contained the best shots from among the soldiers, packers, and scouts. The second detachment came under my own orders. Our pioneer party slipped down the face of the precipice without accident, following a trail from which an incautious step would have caused them to be dashed to pieces; after a couple of hundred yards this brought them face to face with the cave, and not two hundred feet from it. In front of the cave was the party of raiders, just returned from their successful trip of killing and robbing in the settlements near Florence, on the Gila River. They were dancing to keep themselves warm and to express their joy over their safe return. Half a dozen or more of the squaws had arisen from their slumbers and were bending over a fire and hurriedly preparing refreshments for their valorous kinsmen. The fitful gleam of the glowing flame gave a Macbethian tinge to the weird scene and brought into bold relief the grim outlines of the cliffs between whose steep walls, hundreds of feet below, growled the rushing current of the swift Salado.

The Indians, men and women, were in high good humor, and why should they not be? Sheltered in the bosom of these grim precipices only the eagle, the hawk, the turkey buzzard, or the mountain sheep could venture to intrude upon them. But hark! What is that noise? Can it be the breeze of morning which sounds 'Click, click'? You will know in one second more, poor, deluded, red-skinned wretches, when the 'Bang! Boom!' of rifles and carbines, reverberating like the roar of cannon from peak to peak, shall lay six of your number dead in the dust.

The cold, gray dawn of that chill December morning was sending its first rays above the horizon and looking down upon one of the worst bands of Apaches in Arizona, caught like wolves in a trap. They rejected with scorn our summons to surrender, and defiantly shrieked that not one of our party should escape from that canyon. We heard their death song chanted, and then out of the cave and over the great pile of rock which protected the entrance like a parapet swarmed the warriors. But we outnumbered them three to one, and poured in lead by the bucketful. The bullets, striking the roof and mouth of the cave, glanced among the savages in the rear of the parapet and wounded some of the women and children, whose wails filled the air.

During the heaviest part of the firing a little boy, not more than four years old, absolutely naked, ran out at the side of the parapet and stood dumfounded between the two fires. Nantaje, without a moment's pause, rushed forward, grasped the trembling infant by the arm, and escaped unhurt with him inside our lines. A bullet, probably deflected from the rocks, had struck the boy on the top of the head and plowed round to the back of the neck, leaving a welt an eighth of an inch thick, but not injuring him seriously. Our men suspended their firing to cheer Nantaje and welcome the new arrival: such is the inconsistency of human nature.

Again the Apaches were summoned to surrender, or, if they would not do that, to let such of their women and children as so desired pass out between the lines; and again they yelled their defiant refusal. Their end had come. The detachment left by Major Brown at the top of the precipice, to protect our retreat in case of necessity, had worked its way over to a high shelf of rock overlooking the enemy beneath, and began to tumble down great boulders which speedily crushed the greater number of the Apaches. The Indians on the San Carlos reservation still mourn periodically for the seventy-six of their relatives who yielded up the ghost that morning. Every warrior died at his post. The women and children had hidden themselves in the inner recesses of the cave, which was of no great depth, and were captured and taken to Camp McDowell. A number of them had been struck by glancing bullets or fragments of failing rock. As soon as our pack-trains could be brought up we mounted the captives on our horses and mules and started for the nearest military station, the one just named, over fifty miles away."

(4) Nelson Lee, Three Years Among the Comanches (1859)

From the position I occupied I had a fair, unobstructed view of the battle. It was fierce and terrible. The horses reared, and plunged, and fell upon each other, their riders dealing blow for blow, and thrust for thrust, some falling from their saddles to the ground, and others trampling madly over them.

The Comanches outnumbered the enemy; nevertheless, they were forced to retreat, falling back down the hill almost to my position; but still they were not pursued, the Apaches appearing to be content to hold possession of the ground. Soon, the tribe of the Spotted Leopard again rallied and dashed once more to the attack. If possible, this contest was severer, as it was longer than the first. Again the fierce blow was given and returned; again horses and men intermingled in the melee - stumbled, fell, and rolled upon the ground, while the wide heavens resounded with their hideous shrieks and cries.

My blood thrilled through my veins as I looked upon the scene. I had mingled in encounters fierce even as that, but never before in the midst of the hottest fight was I overcome with such a sense of terror. To be an inactive spectator of a battle is far more painful than to be a participator in it.

I hoped devoutly during the engagement that the Comanches would be beaten, being impressed with the belief that if I should fall into the enemies' hands, my chances of escape would be increased, for I had often heard that the Apaches, though a most warlike nation, were more merciful to prisoners than others of their race. But in this I was disappointed. The Apaches at length gave way, disappearing beyond the ridge. Instead of pursuing their advantage, however, the Comanches hastily gathered up their dead and retreated towards the mountains we had crossed.

(5) Lieutenant Kennon recorded in his diary a meeting between General George Crook and Chatto (2nd January, 1890)

We reached the little station of Mount Vernon just before 8 a.m. Country poor, sandy and a growth of small pine. A road took us up to the barracks. An ambulance happened to be at the station, and a sergeant, who resented our getting in until he found out that the 'old gentleman' was General Crook.

The approach to the Barracks, with great green trees on either side was very pretty. The post is walled in by a wall from 12 to 16 feet high, without flanking arrangements. It is situated on a knoll, and above the 'backwater' of the Tombigbee.

We drove direct to the CO's house, rang, and were admitted. No one but the servant was up. Soon Mrs. Kellogg came down, and later the Colonel. There was also a daughter or niece. They were not expecting us. Did not know we were coming, apologized, etc., which was not necessary.

A young Indian with long, black hair saw the General, and before we had finished breakfast. Chihuahua was outside, waiting. He seemed overjoyed to see the General. Kaetena joined him, and we walked over to the Indian village, which was just outside the gate of the fort. They live in little log cabins which had been built for them. At the gate was a considerable number of Indians waiting for us. Chatto came out, and went up to the General, and gave him a greeting that was really tender. He took him by the hand, and with his other made a motion as if to clasp him about the neck. It was as if he would express his joy, but feared to take such a liberty. It was a touching sight.

The Apaches crowded about the General, shaking hands, and laughing in their delight. The news spread that he was there, and those about us shouted to those in the distance, and from all points they came running in until we had a train of them moving with us.

(6) Frances Roe, letter (June, 1873)

When we got out about fifteen miles on the road, an Apache Indian appeared, and so suddenly that it seemed as if he must have sprung up from the ground. He was in full war dress - that is, no dress at all except the breech clout and moccasins - and his face and whole naked body were stained in many colors in the most hideous manner. In his scalp lock was fastened a number of eagle feathers, and of course he wore two or three necklaces of beads and wampum. There was nothing unusual about the pony he was riding, except that it was larger and in better condition than the average Indian horse, but the one he was leading - undoubtedly his war horse - was a most beautiful animal, one of the most beautiful I ever saw.

The Apache evidently appreciated the horse, for he had stained only his face, but this had been made quite as frightful as that of the Indian. The pony was of a bright cream color, slender, and with a perfect head and small ears, and one could see that he was quick and agile in every movement. He was well groomed, too. The long, heavy mane had been parted from ears to withers, and then twisted and roped on either side with strips of some red stuff that ended in long streamers, which were blown out in a most fantastic way when the pony was running. The long tail was roped only enough to fasten at the top a number of strips of the red that hung almost to the ground over the hair. Imagine all this savage hideousness rushing upon you - on a yellow horse with a mane of waving red! His very presence on an ordinary trotting pony was enough to freeze the blood in one's veins.

(7) General George Crook, Autobiography (1889)

All the other Indians having sued for peace, and the Indians occupying this rough country having been so severely chastised, I had some of the prisoners sent out to communicate with the hostiles, holding out the "olive branch," offering them peace on certain conditions, which were that they should all move in on the different reservations and abstain from all depredations from that time forward. They promptly responded to my proposition, and all within reach came in at once.

So, on the seventh day of April, 1873, the last of the Apaches surrendered, with the exception of the Chiricahuas under Cochise, whom General Howard had taken under his wing. Had it not been for their barbarities, one would have been moved to pity by their appearance. They were emaciated, clothes torn in tatters, some of their legs were not thicker than my arm. Some of them looked as if though they had dropped out of a comic almanac.

(8) General George Crook, Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States (October, 1886)

The Apache is becoming a property owner. It is his property, won by his own toil, and he thrills at once with the pride of acquisition, and the anxiety of possession. He is changing both inside and out: exteriorly he is dressed in white man's garb, wholly or in part. Mentally he is counting the probable value of his steers and interested in knowing how much of his corn crop the quartermaster may want next month.

(9) Herman Lehmann, Indianology (1899)

We stayed in camp about a month, killed mustangs, antelope, buffalo, deer, etc., enough to run the old warriors, the manikins and the women until we came back, and then we started on another stealing expedition.

We only took the ponies we rode, each of us mounted on a separate pony, our guns primed and ammunition handy, besides a supply of bows and arrows.

If a horse gave out, that Indian had to take it afoot until he could steal one," but if we got in a tight we took him up behind. We came south-east about one hundred and fifty miles and camped on a little ravine. Scouts were sent out and soon they returned and reported three men headed toward us. We all hid in ambush and made ready, but just as these men rode up we were discovered and fired upon, and one horse was killed. We vigorously returned the fire and they ran, but continued to fight. We caught one man and he spoke Spanish. We asked where his camp was and he told us it was over the mountain, but that it was deserted and that the men were all away chasing buffalo. The Indians left me to guard the prisoner, and they charged over the hill and on to camp, but instead of an easy capture, a volley of balls met them. There was a crowd in camp and they had fortified the place with rock. The Indians were repulsed and one wounded in the leg. The Indians came back and ordered me to murder my prisoner. He picked up a rock and hurled it at me; I dodged the missile and fired in the air but my arm grew steady, and I fired again, killing him instantly. I pounced upon him and soon his bloody scalp was dangling at my belt, and I was the proud recipient of Indian flattery.