English International Matches

Charles W. Alcock, the secretary of the Football Association, arranged the first international football game to be played on the 30th November, 1872. Alcock took a team of English born players to play against a team from Scotland. The match, played in Glasgow, ended in a 0-0 draw. The main objective was to publicize the game of football in Scotland. It had the desired effect and the following year the Scottish Football Association was formed and the England-Scotland match became an annual fixture.

In 1883 the British International Championship was established. Each country met the other three over the course of the season. Scotland won the initial championship by beating England (1-0), Wales (4-1) and Ireland (5-0). The following season Scotland scored 8 against both Wales and Ireland. However, they could only manage a 1-1 draw against England.

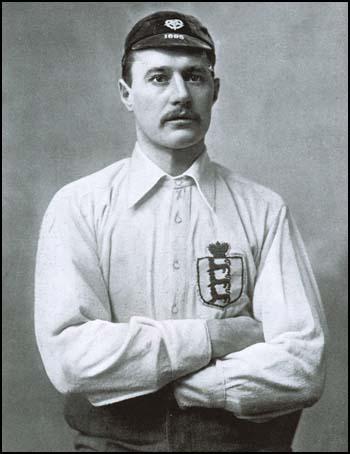

James Forrest won his first international cap for England against Wales on 17th March, 1884. The following year he was selected to play against Scotland. Scottish officials complained as they argued that Forrest was a professional. At the time he was receiving £1 a week from Blackburn Rovers. Forrest was eventually allowed to play but he had to wear a different jersey from the rest of the team.

In 1887 Bob Roberts became England's goalkeeper. Others who played in this position for their country during this period included John Sutcliffe, William Foulke, John Robinson and Herbie Arthur.

Despite being born in Blackburn, in 1890 Jack Reynolds was selected to play for Ireland against Wales. On 15th March, 1890, Reynolds scored Ireland's only goal in their 9-1 defeat against England. In 1891 Reynolds joined Ulster where he won an Irish Cup runner-up medal after losing to Linfield in the final. That season he played in all three of Ireland's games against Wales (7-2), England (1-6) and Scotland (1-2).

Jack Reynolds won his first international cap for England on 2nd April, 1892. Only one other player, E. E. Evans, has been known to play for two of the home countries. Over the next five years he won another seven caps for England. This included victories over Scotland (5-2 and 3-0) and Wales (6-0 and 4-0). Overall he scored three goals in eight games for his country. He is also the only player, barring own goals, to score for and against England.

G.O. Smith was an outstanding goalscorer for his country. Smith was 5 feet 11 inches tall but was of slight build and was extremely reluctant to head the ball. However, he had a good shot and made a lot of goals for his fellow attackers with his accurate passing. Smith won his first international cap on 25th February, 1893. England beat Ireland 6-1 and Smith, who played centre-forward, scored two of the goals.

James Catton pointed out: "Anyone could knock him off the ball if he could get into contact with him. But he was difficult to find, so elusive was he. His value consisted chiefly of wonderfully accurate passes to either wing; either to the inside or the outside man. And his body balance and swerve were such that when he left the arena not a hair of his head was out of place." During his time playing for Corinthians (1898-1901) he scored 113 goals in 131 games. He also had a good record for England scoring 11 goals in 20 games.

Gilbert O. Smith developed a good partnership with fellow striker, Steve Bloomer. According to Frederick Wall, the president of the Football Association, "Smith used to call out "Steve," and he made the position so favourable that in the twinkling of an eye the ball was in the net." Bloomer scored 28 goals in only 23 games during his career and at that time was the only player to score four goals for England twice.

Vivian Woodward, who replaced G.O. Smith as centre-forward in the England team, was also an amateur player. Over an eight year period he had scored 29 goals in 23 games (13 as captain). A record that stood until Tom Finney beat it in 1958. However, Finney played in 72 games for his 30 goals.

In 1893 John Sutcliffe became England's goalkeeper.

For many years Scotland and England dominated the British International Championship. It was not until Ireland was involved in a three-way tie in 1902-03 that there were signs of a shift in power. Wales won the title in 1906-07 and Ireland did it in 1913-14.

After the First World War, Scotland emerged as the leading football power in Britain. Their chief rivals were Wales who won the championship six times between 1920 and 1937.

Primary Sources

(1) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

When England play Scotland at Hampden, England come out first and have to stand on the field while the famous Roar greets the Scots. And that roar is really something. It seems to start behind one goal and then sweep right round the vast bowl that is Hampden. It makes your heart thump and your knees go weak. You can almost see and feel the roar, but the amazing thing is that as soon as the game started the noise didn't worry me at all. Mind you, I did think the fans would shatter the heavens when Dougal put Scotland ahead, but twenty minutes from time, Pat Beasley, playing his first international equalized, and I had the feeling we were getting on top.

The ball was coming through from our wing half backs-what great ones they were that day!-and then, with hardly any time left-it was actually seventy seconds!-Len Goulden sent Stan Matthews away. He skated past McNab, and as we all pressed into the attack, Stan evaded Cummings and sent across a perfect centre. As soon as I saw it leave his boot I knew it was mine, and sure enough it was. I hit it perfectly with my head and the ball simply fizzed into the net. It was a great moment. We had beaten Scotland and the Hampden Roar.

(2) Stan Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

Early in the following season came the first of the Victory internationals. They were full representative games in everything but name, with each country able to choose practically from its full strength. The opening one of these fixtures was at Windsor Park, Belfast, and early in September I was overjoyed to find myself selected. Stan Matthews and Raich Carter formed the right-wing again, the new left-wing pairing being myself and Leslie Smith, with Tommy Lawton in the middle.

This game brought me to full realisation of the genius of Peter Doherty, my opposite number. At the time Peter was very unsettled, because he had practically decided not to resume his old association with Manchester City, but this did not affect his football. There was scarcely a blade of grass he did not cover in the course of a game in which England attacked almost constantly but were held up by a fine defence in which Peter took his full share. Centre-half Vernon, too, was in magnificent shape, and gave many people their first indication that he was to become one of the great " stoppers " of post-war football.

Some of the first-time tackling, although fair enough, could only have been accomplished by an Irish side playing before their own supporters, and for eighty minutes we hammered away without being able to put the ball into the net.

With ten minutes to go, Stan Matthews secured possession, beat one man, drew another, and centred. I was able to run on to it in the manner footballers like best. I took it in my stride, the ball running perfectly for me, and into the net it sailed. Once again I had been fortunate enough to score the winning goal for England.

(3) Nick Varley, Golden Boy (1997)

There was no clearer example than the selection process and the logistics of international games. Winterbottom didn't pick the team, but merely took a note of his choices to the selection committee meeting. The chairman would start the proceedings with a call for "Nominations for goalkeeper". The committee members, all representing different clubs, would put forward their men - often literally their men, their club's stars. The only time they would be less keen would be if their club had a big match looming and they'd prefer to have the best players at home. In those circumstances the other selectors would realize the scam chairman Jones of Town was trying to pull to make sure his players were picked.

Winterbottom's chances of picking the team he wanted were nil. There would be compromises left, right and centre. Then there was the additional headache of doling out caps as honours. A long-serving professional with a distinguished club career coming to an end might be picked to recognize his contribution.

In those days it was a selection committee which basically rewarded players who were good professionals, Sir Walter says. "It was a question of giving them the honour of playing for England, acknowledging their careers really. They were good players, obviously, who deserved recognition at international level, but not always when they got it. I remember when Leslie Compton, who had never won a cap, partly because of the war, was picked for one game as a mark of respect for him playing so long and so well, generally, for Arsenal. It wasn't on really, but that's the way it was - even though you're not going to build up a World Cup winning squad like that, are you?"

Regional alliances were formed, too - the North versus the South versus the Midlands. The chairmen only saw the players who appeared for or against their side. Only later did Winterbottom manage to convince them of the need to take in a few more matches to assess other players. He also managed to revise the system later, so at least he would nominate a side as the basis of the selection committee's deliberations.