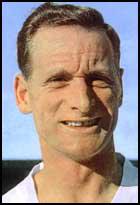

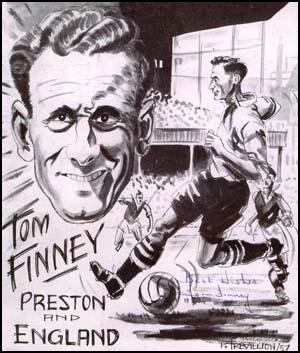

Tom Finney

Thomas Finney was born in Preston on 5th April 1922. He developed a love of football in his childhood: "The kickabouts we had in the fields and on the streets were daily events, sometimes involving dozens and dozens of kids. There were so many bodies around you had to be flippin' good to get a kick. Once you got hold of the ball, you didn't let it go too easily. That's where I first learned about close control and dribbling."

As a young boy he idolized Alex James: "It was a world of make-believe - were children more imaginative in those days? - and although we only had tin cans and school caps for goalposts, it mattered not a jot. In my mind, this basic field was Deepdale and I was the inside-left, Alex James. I tried to look like him, run like him, juggle the ball and body swerve like him. By being James, I became more confident in my own game. He never knew it, but Alex James played a major part in my development."

Finney was a keen footballer but his small size, at 14 he was only 4ft 9ins tall and weighed under 5 stone, meant that he was not considered for national honours. However, his school, Deepdale Secondary Modern, did reach the final of the Dawson Cup which was played at Deepdale, the ground of Preston North End. Finney scored the winning goal and as he later recalled "I was chaired from the field a hero. Scenes of jubilation surrounded the presentation and we were greeted by hundreds of smiling faces when we came out of the ground."

As a schoolboy, Finney, used to watch Alex James play at Deepdale. "James was the top star of the day, a genius. There wasn't much about him physically, but he had sublime skills and the knack of letting the ball do the work. He wore the baggiest of baggy shorts and his heavily gelled hair was parted down the centre. On the odd occasion when I was able to watch a game at Deepdale, sometimes sneaking under the turnstiles when the chap on duty was distracted, I was in awe of James. Preston were in the Second Division and the general standard of football was not the best, but here was a magic and a mystery about James that mesmerised me."

Finney left school at 14 and joined the family plumbing business. However, Jim Taylor, the chairman of Preston North End, decided to create a youth scheme to identify talented young footballers from Preston. This included funding the under 16 Preston and District League. As Jack Rollin explained in (Soccer at War: 1939-45): "By 1938 the club was already running two teams in local junior circles when the chairman James Taylor decided upon a scheme to fill the gap between school leavers and junior clubs by forming a Juvenile Division of the Preston and District League open to 14-16-year-olds."Rollin points out that by 1940 over 100 youngsters were being trained in groups of eight of the club's senior players voluntarily assisting in evening coaching. Robert Beattie was one of those involved in this coaching. One of the first youngsters to emerge from this youth system was Tom Finney.

On Friday, 1st September, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. The football that Saturday went ahead as Neville Chamberlain did not declare war on Germany until Sunday, 3rd September. The government immediately imposed a ban on the assembly of crowds and as a result the Football League competition was brought to an end. However, later that month the government gave permission for football clubs to play friendly matches. In the interests of public safety, the number of spectators allowed to see these games was limited to 8,000. These arrangements were later revised, and clubs were allowed gates of 15,000 from tickets purchased on the day of the game through the turnstiles.

The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place. Preston North End became a member of the North Regional League. Although Finney was only 18 years old, he was considered good enough to play in the first-team. Two other products of the Preston youth system, Andrew McLaren and William Scott, also played in these games.

In 1940 the Football League decided to start a new competition entitled the Football League War Cup. Preston were beaten by Everton in the first round. However, in 1941 Preston beat Bury and Bolton Wanderers in the first two rounds. In the next round nineteen year old Andrew McLaren scored five of the goals in Preston's 12-1 victory over Tranmere. He also scored a hat-trick in the fourth-round tie against Manchester City. Preston reached the final by beating Newcastle United 2-0.

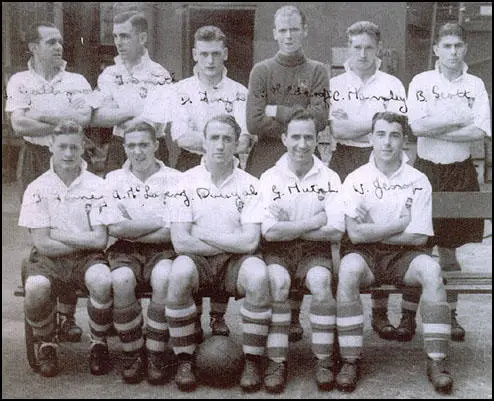

Nineteen year old Tom Finney was picked for the final. The rest of the team that played Arsenal at Wembley on 31st May included: Jack Fairbrother, Frank Gallimore, William Scott, Bill Shankly, Tom Smith, Andrew Beattie, Andrew McLaren, Jimmy Dougal, and Hugh O'Donnell. In front of a 60,000 crowd. Arsenal was awarded a penalty after only three minutes but Leslie Compton hit the foot of the post with the spot kick. Soon afterwards Andrew McLaren scored from a pass from Tom Finney. Preston dominated the rest of the match but Dennis Compton managed to get the equaliser just before the end of full-time.

The replay took place at Ewood Park, the ground of Blackburn Rovers. The first goal was as a result of a move that included Tom Finney and Jimmy Dougal before Robert Beattie put the ball in the net. Frank Gallimore put through his own goal but from the next attack, Beattie scored again. It was the final goal of the game and Preston ended up the winners of the cup. Tom Finney had two great games against England's full-back, Eddie Hapgood, and fully deserved his winners' medal.

In the 1940-1941 season Preston North End needed to win their last game against Liverpool to win the North Regional League title. Andrew McLaren scored all six goals in the 6-1 victory. There is no doubt that during this period Preston was the best football club in England. Other players at the club at the time included Jimmy Dougal, Frank Gallimore, Tom Smith, William Scott, Jack Fairbrother, Bill Shankly, William Jessop, George Mutch, Robert Beattie, George Holdcroft and Hugh O'Donnell. Finney got six goals that season but he was mainly remembered for setting up chances for Dougal, McLaren, Mutch and Beattie.

This great Preston team was broken up by the Second World War. In 1942 Finney was called up to the Royal Armoured Corps. In December 1942 he was sent to fight under General Bernard Montgomery in the Eighth Army in North Africa. "We were posted to a camp next to the pyramids and, with the desert campaign in full swing, thoughts of football disappeared out of my mind. Tom Finney the footballer was now Tom Finney the soldier, involved in all sorts of military manoeuvres, sometimes for 12- and 15-hour streches. The physical demands were punishing in the extreme."

Finney returned to the Preston North End at the beginning of the first season after the war. At 24 he had missed some of his best football years while serving in the British Army. A month later he gained his first international cap playing for England against Northern Ireland. He scored in England's 7-2 victory. The team that day included Raich Carter, Neil Franklin, Wilf Mannion, Tommy Lawton, George Hardwick, Laurie Scott, Frank Swift and Billy Wright.

Finney also scored in his second international game when he netted the only goal in the victory over the Republic of Ireland. Over the next few years Finney was a regular scorer at international level. He added to his total against Holland (November, 1946), France (May, 1947), Portugal (May 1947), Belgium (September 1947), Wales (October, 1947), Scotland (April, 1948), Italy (May, 1948), Wales (November, 1948), Sweden (May, 1949) and Norway (May, 1949). In a game against Portugal in Lisbon on 14th May, 1950, Finney scored 4 goals, in England's 5-3 victory. Finney was later to claim that it was his greatest performance in a England shirt.

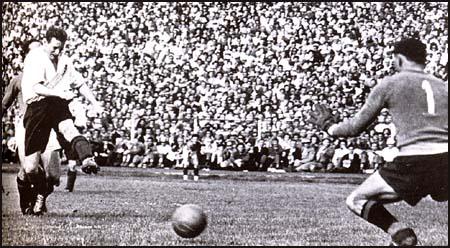

Stan Mortensen played with Finney several times during his international career: "Speed is a curious thing in football. You need to be fast, but only over short distances. A man who can beat his team-mates over a hundred yards may be one of the slowest on the field, where speed is all a matter of bursts over a few yards. More important than absolute speed are acceleration and change of pace, and the knack of getting into your stride quickly. Watch Tom Finney... a master of changing pace. He will amble along, rolling the ball like a dancing-master. When the half-back or back is wondering whether to deliver the tackle, he will suddenly lengthen and quicken his stride in the most surprising fashion. There is the trick of slowing down after a full-speed burst, and then speeding up again. If you can do this, you will not find many defenders able to counter the move."

Tommy Lawton played with both Tom Finney and Stanley Matthews. He was once asked to compare them as players: "Tom Finney always looks deadly serious, but his football has an impish character about it. Much of his footwork resembles that of Matthews, but Finney cuts in more than Matthews does, and is also a goal-scorer, whereas Matthews is content to let others do the scoring. Tom can also play equally well on the left wing, and has shown that he is equally skilful at beating an opponent on the inside as well as the outside. Like Matthews, he has a tremendous burst of speed which helps him to float away from his pursuers."

Matt Busby was asked the same question: "Stan Matthews was basically a right-footed player, Tom Finney a left-footed player, though Tom's right was as good as most players' better foot. Matthews gave the ball only when he was good and ready and the move was ripe to be finished off. Finney was more of a team player, Matthews being more of an inspiration to a team than a single part of it. Finney was more inclined to join in moves and build them up with colleagues, by giving and taking back. He would beat a man with a pass or with wonderful individual runs that left the opposition in disarray. And Finney would also finish the whole thing off by scoring, which Stan seldom did. Being naturally left-footed, Tom was absolutely devastating on the right wing. An opponent never seemed to be able to get at him. If you were a problem to him he had two solutions to you. How can anybody say who was the greater ? I think I would choose Matthews for the big occasion - he played as if he was playing the Palladium. I would choose Finney, the lesser showman but still a beautiful sight to see, for the greater impact on his team. For moments of magic - Matthews. For immense versatility - Finney. Coming down to an all-purpose selection about whom I would choose for my side if I could have one or the other I would choose Finney."

Nat Lofthouse, refused to compare the two players in his autobiography, Goals Galore (1954): "To compare Matthews and Finney is not really possible. They are entirely different in style. Whereas Tom Finney takes the ball no matter how it is sent to him, Stan Matthews prefers it direct to his feet. This, quite naturally, limits a centre-forward's distribution. Stanley does not like a centre-forward to veer out on to his beat, but, as you may have noticed, he frequently draws opponents away from the centre-forward and then pushes over a really peachy pass. I am not risking the wrath of millions of his admirers by criticizing Matthews, but I must say that speaking as a centre-forward I prefer the more direct winger. While Stan is beating defenders out on the touch-line, other members of the defence are given valuable time to get back and cover. As another example of how different in style Matthews and Finney are, I must mention their centres and corner-kicks. Finney... hits the ball over hard and all it needs is a deflection to bring disappointment to a goalkeeper. Matthews' crosses, on the other hand, seem to float in the air. Goalkeepers, and other defenders, coming up against this unusual form of centre, are invariably caught in two minds. For the centre-forward, it means a different approach must be made in heading the ball goalwards. With Matthews' centres I have to put my own power behind the ball; in other words, I try to kick the ball with my forehead. For speed over 20 yards, too, Stanley Matthews remains the fastest of all wingers."

It upset Finney that the media constantly reported that he did not got on with Stanley Matthews. Finney commented in his book, My Autobiography (2003): "Imagine how we both felt, continually reading in the newspapers of a so-called feud between us. Time and time again we tried to put the record straight, but it was almost as if the media didn't want to know. Perhaps the truth would have served only to ruin the stories. So let's put a few myths to bed. I have waited a long time for this. Stan and I shared a mutual respect and a close friendship and I categorically refute all rumours suggesting any kind of bad blood or friction."

Matthews confirmed this in his autobiography The Way It Was (2000): "As a player, he (Finney) was happy operating on either wing. He could also drop into midfield to mastermind a game and, when asked, to play as an out-and-out centre-forward. He was a striker of considerable note, as a career total of 187 goals testifies. He took all the corners, the free kicks, throw-ins and penalties and, such was his devotion to Preston, I reckon he would have taken the money on the turnstiles and sold programmes before a match if they'd let him. On the pitch he made ordinary players look great and helped the great players create the magical moments that for years would be sprinkled like gold dust on harsh working-class lives to create cherished memories that would be recalled to grandchildren on the knee. If greatness in football can be defined by the ability of a player to impose his personality on a match and dominate the proceedings throughout, then Tom Finney, for club and country, was indeed a true great. His delayed spurt, lengthened stride, his ability to beat a man then cut in and shoot and, above all, his cunning use of the ball with both feet, posed insurmountable problems for even the best defenders. The sight of one man dictating the fortunes of a team is one of football's greatest and rarest spectacles. To dictate the pace and course of a game, a player has to be blessed with awesome qualities. Those who have accomplished it on a regular basis can be counted on the fingers of one hand - Pele, Maradona, Best, Di Stefano and Tom Finney."

Finney, considered to be the best player playing in the early 1950s, was unable to bring success to Preston North End. He was in the team that was promoted to the First Division in the 1950-51 season. A team-mate, Bill Shankly, said: "Tommy tore Derby County apart in a match shortly after the war. The pitch was a quagmire, but the mud didn't hinder Tommy at all. He trailed the ball past opponents, cut it across the penalty area, won free kicks and penalty kicks and made Derby wish he was a million miles away. It was one of the most remarkable games I can remember...He was a ghost of a player but very strong. He could have played all day in his overcoat."

In 1952 Prince Roberto Lanza di Trabia, the owner of Palermo, tried to sign Finney. "I was 30 and probably at my peak, playing to the top of my form both for North End and for England, when I received what can only be described as an offer of a lifetime. The approach was made by an Italian prince, owner of the Palermo club in Sicily. Prince Roberto Lanza di Trabia, Palermo's millionaire president, was prepared to pay me £130 a month in wages (plus win bonuses of up to £100), provide me with a Mediterranean villa and a brand new Italian sportscar, and pay for the family to fly over as often as they wished. Oh, and there was the little matter of a £10,000 signing-on fee!" However, the club chairman, Nat Buck, a retired businessman who had made his money out of house building, rejected the offer: "Tom, I'm sorry, but the whole thing is out of the question, absolutely out of the question. We are not interested in selling you and that's that. Listen to me, if tha' doesn't play for Preston then tha' doesn't play for anybody."

Finney later explained: "Deep down, I expected no other reaction, but I was still more than a little put out by the way he just dismissed it. However, I accepted the decision without too much fuss and tried to forget about the whole affair. That was easier said than done. There was a genuine appeal about the prospect of trying my luck abroad, not to mention the money and the standard of living, and I couldn't help but think I might regret this missed opportunity for the rest of my life.... Nat Buck tried to prevent any further inquiry from Palermo - or anywhere else for that matter - by placing £50,000 valuation on my head. That said everything and in some ways it was very flattering. The world record transfer fee of the day was still some way short of £20,000 so it proved just how much Preston valued me."

The club also finished second to Arsenal in 1952-53 and reached the 1954 FA Cup Final. However, he did not have a good game and West Bromwich Albion won 3-2. Finney later wrote: "It turned out to be an unmitigated disaster and a complete embarrassment. The day was a collective and personal disaster.... Unlike most of my team-mates, I had experienced the feel of Wembley before, but if they looked to me for help and guidance they were wasting their time. In the dressing room and walking out from the tunnel I was fine; it was just when the match started that my problems took hold and didn't let go... I had a stinker."

In August 1956 Cliff Britton became manager of Preston North End. One of his first decisions was to play the Finney as centre-forward. Finney scored 23 goals the 1956-57 season and Preston finished third in the First Division. The following season they finished runners-up to Wolverhampton Wanderers.

As Dean Hayes pointed out in Who's Who of Preston North End (2006): "One thing on which all who played with or against Tom Finney agree is that, in addition to all his skill, he never lacked courage. In his time he took a large amount of punishment. this is reflected in the fact that he missed 115 matches - most of them in ones, twos and threes - through injury of one kind of another." As his teammate Bill Shankly once said: "Tom Finney would go through a mountain."

Tom Finney retired in 1959. During his time at Preston North End he scored 210 goals in 473 league and cup games. It is claimed that during that period he earned only £15,000 from football. He explained in My Autobiography (2003): "At my peak, in a structure governed by the maximum wage, my income from a playing year with Preston North End struggled to reach £1,200. When I first signed as a professional it was for shillings - ten bob a match to be precise. That's 50p. So when you read of players now being paid up to £100,000 a week for doing the same job, you might think I would be envious but you would be wrong. I would never criticise players for the amounts they are paid. It is not their fault and I say good luck to them, go out there and grasp the opportunity."

Tom Finney, died on 14th February 2014.

Ideas for lessons on Football and the Second World War

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

The kickabouts we had in the fields and on the streets were daily events, sometimes involving dozens and dozens of kids. There were so many bodies around you had to be flippin' good to get a kick. Once you got hold of the ball, you didn't let it go too easily. That's where I first learned about close control and dribbling.

It was a world of make-believe - were children more imaginative in those days? - and although we only had tin cans and school caps for goalposts, it mattered not a jot. In my mind, this basic field was Deepdale and I was the inside-left, Alex James. I tried to look like him, run like him, juggle the ball and body swerve like him. By being James, I became more confident in my own game. He never knew it, but Alex James played a major part in my development...

We played until our legs gave way - scores of 15-13 were not uncommon - and I never stopped running. I tried to make up in enthusiasm what I lacked in physical presence for all the other boys were much bigger than I was, or so it felt.

Football united the kids. You didn't have to call for your mates; simply walking down the street bouncing a ball had the Pied Piper effect. We could all smell a game from 200 yards.

(2) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

Deepdale Modern signalled the final whistle as far as playtime football sessions were concerned. The building was of a new design, including some all-glass walls, and football in the yard was not permitted. However, the sports teacher (always felt that was a great job) Bill Tuson was particularly keen on football and seemed to take a shine to me. He put me in the school Under-12 team at inside-left - Alex James's position, where else?

We won our way through to the final of the Dawson Cup, one of three major local school tournaments of the day alongside the LFA Cup and the Ord Cup. To get to the final was joy itself, so imagine my reaction when Mr Tuson told us that the venue for the big game was Deepdale.

In common with many other clubs back then, North End officials were only too pleased to stage school and amateur league finals - and why not? Those matches pulled in thousands of people, many of them not regular supporters, so it was not only an excellent public relations exercise but a means of attracting potential new support. I can't think of many places where it happens now. The official line is that the clubs don't want to damage the pitches. I consider that both a poor excuse and a terrible shame.

Considering it was 70 years ago, I can remember the Dawson Cup final of 1934 in a fair bit of detail. St Ignatius' School provided our opposition. The game was played at teatime on a midweek night in the spring, the pitch was shortened and narrowed and we used small nets.

Not much schoolwork was done that day as everyone, pupils and teachers alike, prepared for a Deepdale invasion. The team members met at the ground about half an hour before kick-off and were shown into the main changing rooms. That was a tremendous thrill in itself. North End may have been in the doldrums but the first-team players were still stars to us and here we were using their hooks and benches.

A few of the lads who played that day went on to join the North End groundstaff - Eddie Burke, Cookie Eastham, Dickie Finch and Chuck Scales - but I doubt whether anyone enjoyed it more than I did. For one thing, playing at Deepdale was the stuff of fantasy, especially with my family and friends looking on; for another, I was lucky enough to put my name to the winning goal. Funnily enough, the goal is the one aspect of the night I struggle to recall. It came late on and gave us a 2-1 win.

I was chaired from the field a hero. Scenes of jubilation surrounded the presentation and we were greeted by hundreds of smiling faces when we came out of the ground. It seemed that the whole of Deepdale Modern had turned out.

I stayed with my Grandma Finney and Auntie Martha that night. They had been to the game and were determined to carry on the celebrating with a trip down to the pub. The problem was they wanted to take my medal along with them and I wasn't at all happy about that.

"Do you have to, Grandma?" I pleaded, knowing that I was fighting a losing battle.

"Oh, come on now, Tom," she replied. "Our friends will love to see the medal and hear all about your goal. We will be careful with it, don't worry."

But I did worry. In fact, I couldn't get to sleep for worrying. That medal was the most important thing in my life and the thought of it being passed around a pub was cause enough for concern. I lay there until I heard the key in the front door. Then I jumped out of bed and ran to the top of the stairs.

"Grandma, is that you? Have you remembered my medal?"

They had, of course they had. Such was their pride, the medal could not have been in safer hands. My appetite for football and for Deepdale was well and truly whetted.

(3) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

Although football dominated my early life - that should probably read my entire life come to think of it - opportunities for watching the game were restricted. Apart from anything else, I was always too busy playing. But as a proud Prestonian, I was acutely aware of Preston North End Football Club and, in common with the other lads who kicked a rubber ball around the back fields of Holme Slack, my dream was to be the next Alex James.

James was the top star of the day, a genius. There wasn't much about him physically, but he had sublime skills and the knack of letting the ball do the work. He wore the baggiest of baggy shorts and his heavily gelled hair was parted down the centre. On the odd occasion when I was able to watch a game at Deepdale, sometimes sneaking under the turnstiles when the chap on duty was distracted, I was in awe of James. Preston were in the Second Division and the general standard of football was not the best, but here was a magic and a mystery about James that mesmerised me.

The man behind Preston's capture of James was chairman Jim Taylor, who later signed me and went on to play a major part in my early career.

The son of a railwayman and a native of North Lanarkshire, Alex James was a steelworker when his football talents were first spotted by Raith Rovers in the year of my birth. He earned good money north of the border - £6 in the winter and £4 in the summer - and his form brought the scouts flocking in. Preston were always well served with 'spies' in Scotland and while his short stature and dubious temperament caused a few potential buyers to dither, Jim Taylor was more bullish. In the June of 1925, the chairman went in with a £2,500 bid - an offer later raised to £3,500 to ward off a late inquiry from Leicester City. Taylor had his man and the signing of James proved a masterstroke. The supporters loved him, a fact reflected in the attendances, which rose by around £300 per game. He was box office, the draw card, a player who grabbed your attention and refused to let go.

James was a character off the field, too. He liked clubs - of the night-time variety - owned a car and, by all accounts, enjoyed playing practical jokes on his colleagues. But he was also a perfectionist, a footballer acutely aware of both his ability and his responsibility. The experts scratched their heads about why his talent was being allowed to languish outside the top flight and it wasn't long before Arsenal came in to present him with a bigger stage. He was my first football hero and my role model and when he was transferred to the Gunners I thought I would never get over it.

(4) Dean Hayes, Who's Who of Preston North End (2006)

One thing on which all who played with or against Tom Finney agree is that, in addition to all his skill, he never lacked courage. In his time he took a large amount of punishment. this is reflected in the fact that he missed 115 matches - most of them in ones, twos and threes - through injury of one kind of another.

(5) Bill Shankly, Shankly: My Story (1977)

At Leeds one day - it was the season Leeds went down right after the war - Tommy Finney turned them inside out. He had the goalkeeper demented, not knowing whether Tommy was going to cut the ball back or cross it. Tommy rolled a couple into the net. He had the goalkeeper out of his goal so much that in the end Tommy just put the ball on the left foot and put it inside the near post himself.

Tommy tore Derby County apart in a match shortly after the war. The pitch was a quagmire, but the mud didn't hinder Tommy at all. He trailed the ball past opponents, cut it across the penalty area, won free kicks and penalty kicks and made Derby wish he was a million miles away. It was one of the most remarkable games I can remember, because we won 7-4 and I scored three goals in a game for the only time in my career.

I scored a goal from a free kick, another from a penalty, and the third was a bit of a fluke. I chipped the ball and it rolled into the net. I scored two penalties in the wartime Cup semi-final against Newcastle, but that game against Derby at Preston was the only time I scored three. Raich Carter was with Derby then, and so was little Billy Steele, a great inside forward from Scotland. Angus Morrison, a big centre-forward, also scored three goals, and Preston signed him after that match.

Tommy was injured regularly, and when he was a boy the other players in the team used to look after him a bit in matches. I remember playing in one game when an experienced Scottish player threatened Tommy. He said, "I'll break your leg." I heard this, so I went over to the player and I told him, "Listen, you break his leg and I'll break yours. Then we'll both be finished, because I'll get sent off." He didn't bother Tommy after that.

Tommy was always a civil boy, courteous to everyone. I wouldn't say he cracked jokes in the dressing-room, but he didn't have to. We had enough comedians. We could laugh because we knew Tommy was on our side.

(6) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

I was a one-club man, and by no means unique in that. There were many others - Billy Wright at Wolverhampton Wanderers and Nat Lofthouse at Bolton Wanderers to name but two high-profile England internationals of my era. We were forever being praised for our loyalty, but it wasn't necessarily loyalty by choice. I cannot speak for the others, but I will say this. Had my career started in 2000 and not in 1940, I very much doubt that I would have spent it all at Preston. For one thing, I don't think the system would have allowed it. The financial pressure to move, probably abroad, would have taken charge.

The maximum wage took away a financial incentive to move, and contracts made moving very difficult. Preston was a big club then and I was very happy there, married with a young family and settled in the town with a successful plumbing business. So if Arsenal, probably the top club of the time, had made a bid for me (if they ever did, no one mentioned it!) what would have been my reasons for giving it consideration? Prestige? Possibly. Money? Certainly not. The Arsenal top earners were only on the same as me and with the cost of living in London being substantially higher than in Lancashire, I could actually have ended up worse off.

Now had Arsenal or Newcastle United or any of the other leading clubs been able to come in with an offer to double my wages, I would probably have signed even though I always considered Preston North End to be the greatest club in the world. What is so terribly wrong with a free market place?

I am also a lifelong advocate of star pay for star play. David Beckham, as the star turn with Manchester United, demands a substantially bigger salary than others within the same team. People would expect that and quite right, too. But it didn't apply to us; we got the same as everyone else. There were those who said it helped team spirit and morale and that is as maybe, but it certainly didn't do anything to boost the morale of the star turns.

So in English football of the post-war period, you tended to stay put. However, in May of 1952, I did come very close to being one of the first English footballers to snap up a big-bucks offer from overseas until North End put the mockers on it.

I was 30 and probably at my peak, playing to the top of my form both for North End and for England, when I received what can only be described as an offer of a lifetime. The approach was made by an Italian prince, owner of the Palermo club in Sicily.

Prince Roberto Lanza di Trabia, Palermo's millionaire president, was prepared to pay me £130 a month in wages (plus win bonuses of up to £100), provide me with a Mediterranean villa and a brand new Italian sportscar, and pay for the family to fly over as often as they wished. Oh, and there was the little matter of a£10,000 signing-on fee!

The Prince was desperate to turn Palermo into Italy's top club and, by all accounts, he had drawn up a shopping list of potential signings. I was the top target and he was ready to give me the earth. All I had to do was say yes to a two-year deal. At the end of the contract I would be free to return to England. He knew there would be an outcry at Preston and he told me privately that he was perfectly willing to compensate North End for my absence or pay them a straight transfer fee of around £30,000 if they preferred.... "I want to take Palermo to the very top and I would like you to sign. I would be prepared to give you..." and he ran through the details of the offer, the money, the villa, the plans...

Elsie realised that I had something to tell her the moment I got back home and her reaction was exactly as anticipated.

"It sounds wonderful," she said. "I'll leave the decision to you, Tom, but what about all the upheaval, schooling for the children and how will Preston react?"

There was only one way to find out. I rang Nat Buck, the North End chairman, a retired businessman who had made his money out of house building.

"Sorry to bother you, Mr Buck, but I wonder if I could request a meeting with the board."

"What's on your mind, Tom?" he inquired, in his broad Lancastrian accent.

"Well, it's something of a personal nature so I really would appreciate the chance to speak face to face." He didn't push me for details and we fixed up an appointment to meet at Deepdale.

"Right, Tom. What's going on?" he said, when I got there. Nat was not a man to mince his words. Renowned as a straight-talker - I liked him for that - he seemed to relish controversy and the profile that usually went with it.

"Well, as I said the other day, I would really rather put this matter to the board as a whole. I think it's the right and proper thing to do," I responded.

"No need for that at this stage," said the chairman. "Tell me and I'll decide whether it needs to go before anyone else."

To say that he was unimpressed with my story would be grossly to understate the truth. He just brushed it all to one side and refused point blank to consider it, saying there was nothing to discuss and it was all too silly for words. I told him that the idea appealed to me, I had given it a lot of thought and had promised the Prince I would get back in touch. He remained unmoved. No, more than that, he was angered.

"Tom, I'm sorry, but the whole thing is out of the question, absolutely out of the question. We are not interested in selling you and that's that. Listen to me, if tha' doesn't play for Preston then tha' doesn't play for anybody."

Deep down, I expected no other reaction, but I was still more than a little put out by the way he just dismissed it. However, I accepted the decision without too much fuss and tried to forget about the whole affair.

That was easier said than done. There was a genuine appeal about the prospect of trying my luck abroad, not to mention the money and the standard of living, and I couldn't help but think I might regret this missed opportunity for the rest of my life.

Prince Roberto didn't make it easy for me, either. He was disgruntled by North End's `nothing doing' stance and he came back and tried to set up a deal to borrow me for a season. It basically amounted to the first known example of the loan system that now operates within the global game. But the regulations of the day didn't allow for such a move. I was registered to the English FA and under the Federation of International Football Association's rules, I could not move to Palermo in any circumstances without a clearance certificate. As a rider, the official line stated `temporary transfers will not be approved' and Nat Buck tried to prevent any further inquiry from Palermo - or anywhere else for that matter - by placing £50,000 valuation on my head. That said everything and in some ways it was very flattering. The world record transfer fee of the day was still some way short of £20,000 so it proved just how much Preston valued me.

(7) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

As a 20-year-old, he came in to the Preston side for the 1941 Wartime Cup final against Arsenal. Three days later he joined the Eighth Army in North Africa and spent the rest of the war fighting Rommel. Suffice to say, Rommel lost. It was not until 1946, after being de-mobbed, that he finally played his first official league match for his beloved Preston. Less than a month later, he won the first of his 76 caps against Northern Ireland.

Tom exploded on to the British football scene like one of the heavy artillery shells he had administered in the deserts of North Africa. As a player, he was happy operating on either wing. He could also drop into midfield to mastermind a game and, when asked, to play as an out-and-out centre-forward. He was a striker of considerable note, as a career total of 187 goals testifies. He took all the corners, the free kicks, throw-ins and penalties and, such was his devotion to Preston, I reckon he would have taken the money on the turnstiles and sold programmes before a match if they'd let him.

On the pitch he made ordinary players look great and helped the great players create the magical moments that for years would be sprinkled like gold dust on harsh working-class lives to create cherished memories that would be recalled to grandchildren on the knee. If greatness in football can be defined by the ability of a player to impose his personality on a match and dominate the proceedings throughout, then Tom Finney, for club and country, was indeed a true great. His delayed spurt, lengthened stride, his ability to beat a man then cut in and shoot and, above all, his cunning use of the ball with both feet, posed insurmountable problems for even the best defenders.

The sight of one man dictating the fortunes of a team is one of football's greatest and rarest spectacles. To dictate the pace and course of a game, a player has to be blessed with awesome qualities. Those who have accomplished it on a regular basis can be counted on the fingers of one hand - Pele, Maradona, Best, Di Stefano and Tom Finney.

Looking back, it is remarkable how often I believed Tom would contrive to win a game for Preston and no less remarkable how often he obliged. He didn't always fall into his best vein immediately. Often at the start of a match there was a feint hint of hauteur, almost condescension in a demeanour not dissimilar Raich Carter's. But after a few minutes, having sized everything and everyone up, he would get down to realities and with scintillating speed of foot, draw a cordon behind him and impose his considerable talents and skills on a game in no uncertain manner.

Preston played football in what we called the Scottish style. They held the ball close before distributing it to feet. It was a style that demanded accurate passing, which suited Tom, a player of thoughtful, careful passing, along the ground. As a winger, Tom was more direct than me. He was lightning quick and to see him in full flight, bearing down on jittery defenders, was one of football's finest sights. Even at international level, he was equally at home on either wing, in midfield or at centre-forward. The only problem he posed for managers, was where to play him.In 1952, the Italian side Palermo came in for him. At a time when he was earning around £12 a week, they offered him a £10,000 signing-on fee, £130 a month plus bonuses, a villa and a sportscar. Tom went to see the Preston chairman to discuss the matter. The chairman huffed and puffed when he read the offer from the Italians and told Tom, "Tha'll play for us, or tha'll play for nobody." Tom stayed and saw out his career with his home-town club, clocking up 433 league matches between 1946 and 1960.

(8) Stan Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949)

Speed is a curious thing in football. You need to be fast, but only over short distances. A man who can beat his team-mates over a hundred yards may be one of the slowest on the field, where speed is all a matter of bursts over a few yards. More important than absolute speed are acceleration and change of pace, and the knack of getting into your stride quickly.

Watch Tom Finney... a master of changing pace. He will amble along, rolling the ball like a dancing-master. When the half-back or back is wondering whether to deliver the tackle, he will suddenly lengthen and quicken his stride in the most surprising fashion. There is the trick of slowing down after a full-speed burst, and then speeding up again. If you can do this, you will not find many defenders able to counter the move.

(9) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

Another great sportsman is Tom Finney, that slightly built plumber from Preston. Tom, who was discovered in war-time football, always looks deadly serious, but his football has an impish character about it. Much of his footwork resembles that of Matthews, but Finney cuts in more than Matthews does, and is also a goal-scorer, whereas Matthews is content to let others do the scoring.

Tom can also play equally well on the left wing, and has shown that he is equally skilful at beating an opponent on the inside as well as the outside. Like Matthews, he has a tremendous burst of speed which helps him to float away from his pursuers.

No doubt the biggest tragedy of Tom's career was a couple of seasons back when he had a troublesome injury, and this affected him so much in the Cup Final that he had a wretched game and his side lost by a last-minute goal.

(10) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

I vividly recall Neville Chamberlain's depressing broadcast to the nation on that Sunday morning, 3 September 1939, two days after German forces had invaded Poland. After attending morning service at St Jude's, I called in on a mate of mine, Tommy Johnson, a fellow plumber, and he was glued to the wireless as the news we all dreaded came through.

League football was suspended, players were told that they would be paid up to the end of the week only, and supporters were informed that there would be no refund on season tickets. Andy Beattie, another of North End's 'Great Scots' and a man for whom I held the utmost respect, was due a richly deserved benefit match. The war ensured that didn't materialise. Contracts were effectively cancelled although clubs retained players' registrations.

Preston made strenuous efforts to get players fixed up with jobs - Bill Shankly found employment shovelling sand, George Mutch building aeroplanes and Jack Fairbrother joined up as a policeman. Troops were stationed at Deepdale, and police and military use of the ground continued through until 1946.

Wartime football was no substitute for the real thing but it did serve a purpose. There were restrictions galore and most clubs found their squads decimated through call-ups into the armed services, but the public passion for football won through. Sometimes matches were in doubt right up to kick-off as clubs tried desperately to recruit some guest players, but when the action rolled it was good. Football provided the country with some much-needed escapism and, speaking as a player, it was thoroughly enjoyable - despite the bombs. After we had lost 2-0 at Anfield, our coach-ride home was caught up in an air-raid on Merseyside and that was a frightening experience by any standards.

The 1940-41 season was a shortened affair but Preston United did well. We finished as Northern Section champions, which was some achievement considering the fact that we had struggled at the wrong end of the First Division up to war being declared.

(11) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

Speaking as a centre-forward Tom Finney's the finest all-round forward I've ever played with. On either wing, or at inside-forward, Tom's ability to beat a man and be off on his own, or release the ball quickly and accurately, has brought his team dozens of goals. Personally I shall always remember his masterly flick to me which brought the winning goal against Austria in Vienna.

There's another side to Tom Finney's play which the man on the terraces or in the grandstand may miss: it's the Preston star's strong and accurate tackling. By his sense of perfect timing Tom must be regarded as one of soccer's best tacklers. When he loses the ball he does not stand, hands on hips, and leave it to the defence to save the day.

Tom Finney will always fight to regain possession. For the fellows who play behind him he is indeed a joy-boy to have in the side.

What of Finney's accurate crosses? As the fellow who has the job of trying to nod them past the goalkeeper, I must say I've never found anyone to beat Tom in this specialized field. Finney's crosses are very hard-made, almost with the power of a shot-and all you have to do is deflect the ball. It goes in like a bullet. I'll let you into a little secret. When I'm practising with Tom, and he sends over those tailor-made crosses, I get a tremendous thrill out of flicking them into the net. They bring about "copy-book" goals of the type you remember long afterwards. Another thing about Tom Finney is that he never asks you to place the ball to him in any one position. They all come alike to Tom, a very great footballer, and an artist even the people of South America - accustomed as they are to seeing masterly ball players - hailed as the best they'd seen in years.

(12) Len Shackleton, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955)

No other form of civil employment places such restrictions on the movements of individuals, while, at the same time, retaining the power to dismiss them summarily. If a man is able to better himself in a job elsewhere, he should be free to take that job on providing he has fulfilled his contract. It happens in every walk of life, but not in football. Tom Finney, Preston North End's international outside-right, was told he would be a rich man for life if he spent five years playing football on the Italian Riviera. Whether or not Tom was keen to accept this offer-made by an Italian prince - it would surely have been a waste of his time to consider it because Preston would hardly think of allowing him to say "Yes".

(13) Matt Busby, Soccer at the Top (1973)

Stan Matthews was basically a right-footed player, Tom Finney a left-footed player, though Tom's right was as good as most players' better foot. Matthews gave the ball only when he was good and ready and the move was ripe to be finished off. Finney was more of a team player, Matthews being more of an inspiration to a team than a single part of it. Finney was more inclined to join in moves and build them up with colleagues, by giving and taking back. He would beat a man with a pass or with wonderful individual runs that left the opposition in disarray. And Finney would also finish the whole thing off by scoring, which Stan seldom did. Being naturally left-footed, Tom was absolutely devastating on the right wing. An opponent never seemed to be able to get at him. If you were a problem to him he had two solutions to you.

Tom Finney could and would and did play in any forward position. Like Stan Matthews he was never in any trouble with referees. Stan was knighted after his immense period as a player. Tom was awarded the OBE. I do not say that Tom should have played until he was fifty. I do say that I was sorry he did not play for two or three years more than he did, even though he was in his late thirties.

How can anybody say who was the greater ? I think I would choose Matthews for the big occasion - he played as if he was playing the Palladium. I would choose Finney, the lesser showman but still a beautiful sight to see, for the greater impact on his team. For moments of magic - Matthews. For immense versatility - Finney. Coming down to an all-purpose selection about whom I would choose for my side if I could have one or the other I would choose Finney.

(14) Nat Lofthouse, Goals Galore (1954)

Tom Finney, the great Preston North End and England winger, must have been fouled more than any other player in history in matches abroad, but I have never seen Tom, badly hurt as he may have been, turn to see who brought him down. Finney rises to his feet and looks straight ahead. You will never see the pride of Preston stooping to argue.

During a close-season tour Tom Finney had a terribly rough passage after he had time and again beaten the opposing left-back. Tom kept sliding past this defender like a wraith. Every time he swung over a hard centre it spelt danger for our opponents, and their manager, sitting on the touch-line, nearly exploded with rage. I distinctly saw him give instructions to the defender to up-end Finney. He kept punching one fist into the palm of his hand and then pointing at Finney. A minute or so later Tom was brought down with a tackle which would have been out of place even at Twickenham. The crowd roared with disgust at the action of their own player. If it had been some other teams I know a free fight would have developed. But nothing like this took place. Tom, although badly shaken, and looking white, picked himself up and got on with the game. Even when other defenders began to throw their weight about, our footballers did not retaliate. The outcome? The spectators began to turn against their own team. Everything the English team did was applauded-and next day the newspapers came out with glowing tributes to our sportsmanship.

I made this point to illustrate that traditional British sportsmanship is still appreciated, and I must stress that it starts from our approach to the game as played between clubs in this country.

(15) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

At my peak, in a structure governed by the maximum wage, my income from a playing year with Preston North End struggled to reach £11,200. When I first signed as a professional it was for shillings - ten bob a match to be precise. That's 50p. So when you read of players now being paid up to £100,000 a week for doing the same job, you might think I would be envious but you would be wrong. I would never criticise players for the amounts they are paid. It is not their fault and I say good luck to them, go out there and grasp the opportunity.

The whole deal was so wrong in the forties and fifties. Then, when Jimmy Hill and co. eventually managed to bring about major changes, they were labelled as money-grabbing mercenaries, but I have yet to meet any working man who would turn up his nose at a huge salary. Who would look their boss squarely in the eyes and say, "Well, thanks for the offer, but I will have to decline because I really don't think I'm worth it"?

It is easy to huff and puff and shake your head in judgement and condemnation, and I must concede that six-figure weekly wages and £50 million transfer fees do take a bit of understanding, but footballers' pay has proved a contentious subject since the dawn of professionalism. I was unfortunate in that the maximum wage was abolished the year after I finished. I say unfortunate because I would have loved to earn more, but I also believe that football treated Tom Finney well. I was never ungrateful, but there were times when I did feel the system was mightily unfair on players, and good players in particular. You were basically denied your right to earn your worth because a limit existed, and I found that fundamentally wrong. Every worker, from footballer to office clerk, farm labourer to accountant, entertainer to shop assistant, should be paid according to their ability - paid their worth in other words. A uniform wage scale might have made life easier for the administrators back in the prehistoric days of the 1950s, but it did not excuse the basic injustice towards the players.

I think the powerful men on the football committees were frightened by the prospect of opening up the system, fearful that only those clubs with the best resources, the wealthy minority, would be able to attract the top stars. They were, of course, quite right to be concerned. The vast majority of players would most certainly have moved to the clubs paying the biggest wages. Those in authority back then stifled football's progress in my opinion. They didn't want to threaten the status quo by allowing the game to develop and produce a rich versus poor scenario.

I was a supporter of a Premier League long before the Premiership came into being. I always believed that a strong top end would raise the standards within our game and improve our chances on the world stage. In fact, I put my name to several articles in both regional and national newspapers, so my ideas and beliefs were well aired. I was considered media friendly and I was outspoken, particularly on matters of finance, publicly questioning the system and the people who made the rules. I called not only for the abolition of the maximum wage, but for international fees to be doubled.