Len Shackleton

Leonard (Len) Shackleton was born in Bradford on 3rd May 1922. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Crown Prince of Soccer: "Although there was no official football session at school, I spent all my spare time kicking a ball about in the school yard, in the fields near our home and even in the house, the latter with full parental approval. In the early 1930's, when television was merely a madman's mirage, when empty pockets put the cinema out of bounds, youngsters manufactured their own entertainment with a tennis ball."

Shackleton's parents could not afford to buy him football kit: "I could not afford real football boots so my Uncle John bought some studs and hammered them into an old pair of shoes. Uncle John always wanted me to be a footballer and he realized how much I would appreciate those studded shoes."

A teacher recognized Shackleton's talents and arranged for him to play in the North against the Midlands schoolboy game at York. He was only 4 feet 11 inches tall and was the smallest boy in the game. He was a great success and was selected to play for England Schoolboys in 1936. He scored two goals in England's 6-2 victory over Wales. He was also in the England team that beat Scotland (4-2) and Northern Ireland (8-3).

In August 1938 Shackleton was persuaded by George Allison to sign for Arsenal. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Crown Prince of Soccer: "With neighbours still gossiping outside, Mr Allison painted rosy Highbury pictures inside, with Dad, Mum, and "young Leonard" hanging on every word. He had no need to "sell" Arsenal to me. At that time, any 15-year-old boy, invited to join the greatest club in the world, would have been out of his mind to think twice. So it was that I accepted his offer of a job on the ground staff and signed as an amateur."

The Arsenal team at that time included players such as Ted Drake, Cliff Bastin, Eddie Hapgood, George Male, Reg Lewis, George Swindin, Bernard Joy, Alf Kirchen, Leslie Jones, George Hunt, Leslie Compton and Dennis Compton. However, he was loaned out to Enfield Town who played in the Athenian League.

Shackleton only played two non-league games for Arsenal before he was told by George Allison that he was not going to be offered a professional contract. "Mr Allison could not have been kinder: he handled that interview with diplomacy, repeatedly assuring me that he was advising me in my own interests, and told me not to take the news too badly. One day I would be grateful." Allison added: "Go back to Bradford and get a job. You will never make the grade as a professional footballer."

on the outbreak of the Second World War and was killed on 23rd December 1943.

Shackleton found work at the London Paper Mills at Dartford. On the outbreak of the Second World War he returned to Bradford and after playing a couple of trial games Shackleton was signed by Bradford Park Avenue in August 1940. The Football League was suspended during the war but he made his debut in a friendly game against Leeds United on 25th December 1940.

Shackleton worked on aircraft wireless for GEC during the week. He volunteered for the Royal Air Force but was turned down because his war-work was considered too important. Later, he became a Bevin Boy and worked as a miner at Fryston Colliery near Castleford.

In October 1946 Stan Seymour, the manager of Newcastle United, signed Shackleton for a record fee of £13,000. While at Bradford Park Avenue he had scored 171 goals in 217 games. However, his unusual style of playing was not always appreciated and received a fair amount of barracking from the fans. When he was sold to Newcastle Stanley Matthews commented: "The £13,000 transfer of Len Shackleton from Bradford to Newcastle United is another proof of the harm unsporting spectators can do to players and clubs."

Shackleton made his debut for his new club against Newport County on 5th October. He scored six goals in the record 13-0 win. Jackie Milburn later commented: "On his debut against Newport County he scored six goals, a Division Two record, and put the last one in off his backside. Ever the showman, Shack always preferred to get applause for some daft trick rather than scoring a straight-forward goal."

It was hoped that Shackleton would help Newcastle United get promotion to the First Division. However, they only finished in 5th place with Shackleton scoring 19 goals in 32 league games. They did much better in the FA Cup and reached the semi-final where they were beaten by Charlton Athletic 4-0.

Shackleton developed a great partnership with Jackie Milburn. He later told his son: "Len Shackleton was a master craftsman and thanks to him I got among the goals. I clicked with him because I expected the unorthodox. If he ran one way, I ran the other, and sure enough the ball always found me. On the other hand, Len's quick-witted humour often caused me to laugh outright and lose control of the ball."

Not everyone appreciated the skills of Shackleton. His captain, Joe Harvey, argued that Shackleton was developing into a crowd entertainer rather than a team footballer and seemed more interested in beating four or five men than passing the ball to a better positioned team-mate. He added that "Newcastle would never win anything with him in the team". In February 1948 Newcastle United sold Shackleton to Sunderland in the First Division for the record fee of £20,050.

Shackleton won his first international cap for England against Denmark on 26th September, 1948. England drew the game 0-0. The England team that day included Stanley Matthews, Tommy Lawton, Laurie Scott, Jimmy Hagan, Billy Wright and Frank Swift.

Shackleton retained his place for the game against Wales but over the next six years he only played in three more games for his country. A journalist asked an England selector: "Why is Len Shackleton consistently left out of the England team?" The selector replied: "Because we play at Wembley Stadium, not the London Palladium".

Stanley Matthews argued in his autobiography, The Way It Was, that Shackleton was "unpredictable, brilliantly inconsistent, flamboyant, radical and mischievous; in short, he possessed all the attributes of a footballing genius which he undoubtedly was." Matthews claimed that he had a superb game against Germany in 1954 but it was the last time he played for England. As Matthews pointed out that his behaviour did "not go down well with the blazer brigade who ran English football and had such an important say in the selection of the England team."

Sunderland finished in 3rd place in the 1949-45 season. However, over the next few seasons the club went into decline and Shackleton failed to win any league or cup medals while he was at Roker Park. He also suffered from a serious ankle injury and was forced into retirement. He had scored 101 goals in 348 games for the club.

Shackleton worked as a football journalist with the Daily Express and the Sunday People. He also wrote a controversial autobiography, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955). Chapter 9 was entitled "The Average Director's Knowledge of Football". This was followed by a note from the publisher: "This chapter has deliberately been left blank in accordance with the author's wishes."

Len Shackleton died at Grange-over-Sands on 27th November 2000.

Ideas for lessons on Football and the Second World War

Primary Sources

(1) Len Shackleton, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955)

Ever since I started putting two and two together - and that was a long time ago - I have had a passionate interest in football. As an elementary school kid, playing no organized Saturday afternoon soccer, off I would trot with Dad to Valley Parade one Saturday, Park Avenue the next... dividing my affections equally between the two Bradford clubs. Footballers normally become spectators when they are too old to play, but I was a keen fan before starting to play.

Although there was no official football session at school, I spent all my spare time kicking a ball about in the school yard, in the fields near our home and even in the house, the latter with full parental approval. In the early 1930's, when television was merely a madman's mirage, when empty pockets put the cinema out of bounds, youngsters manufactured their own entertainment with a tennis ball. From May to August we were all budding Herbert Sutcliffes or Hedley Veritys. In the winter we became Cliff Bastins and Dixie Deans. Even though youngsters stuck to their seasons religiously, the same tennis ball and pile of coats were utilized for equipment.

Whenever Mum told me to go on an errand, I would make sure I had a pal to keep me company, produce the tennis ball the minute we left the house, pass and re-pass it all the way to the shops and back, and hardly notice I had performed the loathsome task of shopping. Refusing to be robbed of football time after dark, our gang played many a "cup-tie" in front of a well-lit grocery shop...

Like Jimmy Hagan, Wilf Mannion and the other over-30's, I was fortunate enough to be brought up in an age of football enthusiasm. As a seven-year-old, I could not afford real football boots so my Uncle John bought some studs and hammered them into an old pair of shoes. Uncle John always wanted me to be a footballer and he realized how much I would appreciate those studded shoes.

Dad didn't appreciate them so much the first time I tried them out. Every evening, Sundays included-we were not answerable to the Football Association then-the decks were cleared in the Shackleton living-room for indoor football. Chairs were removed from the room, while furniture too bulky to evict was pushed into a corner, though as a slight concession to the landlord's window panes, a ball of paper bound with elastic bands was substituted for the tennis ball.

(2) Len Shackleton, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955)

With neighbours still gossiping outside, Mr Allison painted rosy Highbury pictures inside, with Dad, Mum, and "young Leonard" hanging on every word. He had no need to "sell" Arsenal to me. At that time, any 15-year-old boy, invited to join the greatest club in the world, would have been out of his mind to think twice. So it was that I accepted his offer of a job on the ground staff and signed as an amateur.

I thought August would never come, but eventually I packed my bags, caught the train to London, and was met at King's Cross by Jack Lambert, centre-forward hero of so many Arsenal triumphs. Jack had finished his playing career but, like other Arsenal servants, had become a staff man, as coach to the younger players. Having been installed in Highbury Hill lodgings, I went with Lambert, for my first peep at the magnificent Arsenal stadium. It was a real eye-opener. Villa Park, on which I had played as a schoolboy international, was my idea of soccer perfection, but even Villa Park appeared shabby as I gazed glassy-eyed at Highbury for the first time.

The mighty stands, the spotlessly-clean terracing, reaching, to my eyes, into the clouds, the emerald green turf: these would have been sufficient to impress the bumpkin from Bradford, but to cap the lot, I saw and recognized immediately-several of the favoured, fabulous, footballers, who had helped to make Arsenal great, helped, in fact, to make Arsenal 'The' Arsenal. There they were, within hailing distance, Ted Drake, Wilf Copping, Cliff Bastin and George Male, yet I did not dare hail them, even with a "good afternoon".

The following morning I was handed my equipment, and it didn't include football boots, shirt or shorts. I was given a pair of overalls and told to follow the motor mower all over the pitch clipping any long grass stalks missed by the mower. A rake was provided too, but never a sign of a football. Enviously, I watched the "real" players doing their training stint-while I pretended to rake the gravel or cut the turf, without having the heart for either task. Each day a fresh face would join the stalk-shortening squad: among my companions were Les Henley, later to become an Arsenal first team player, Stan Morgan, who contributed so much to Leyton Orient's promotion drive in 1954-5, Bobby Daniel, brother of Sunderland's Welsh international pivot Ray 'Bebe' Daniel, and Harry Ward, another product of the Leeds League. Bobby Daniel looked like becoming a really great player, until his tragic death in the RAF during the war.

In 1938 Arsenal staggered the football world by signing inside-forward Bryn Jones from Wolverhampton Wanderers for £14,000, a fee described by many a critic as the height of lunacy - but, of course, critics have been saying exactly the same thing since AIf Common moved from Sunderland to Middlesbrough for £1,000. And they will be repeating it when somebody in this country moves for £50,000, which could happen anytime.

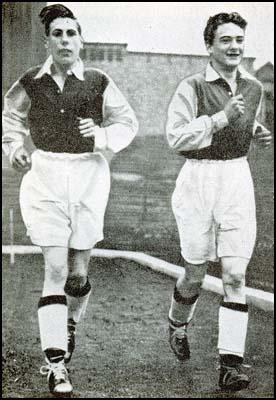

One newspaper decided it would be a good stunt to get a picture of Bryn, Arsenal's costliest player, alongside their cheapest - and they selected me for the job. In the paper there was a wonderful action picture of Bryn Jones, accompanied by the caption, "He cost £14,000". Alongside was "Muggins", in overalls, stalk-shortening with a pair of grass clippers, and the caption, "He cost nothing".

I suppose it made me look a bit of a chump but I did not bear Bryn any malice: though to emphasize what an up-and-down business football is, it is worth mentioning that after the war I was transferred from Newcastle United to Sunderland for a record £20,050 fee at about the same time that Bryn Jones, then a veteran, moved from Highbury to Norwich City in exchange for a relatively small fee-certainly not more than £3,000.

Record fees did not concern me in 1938, however. I was more worried about hiding myself from the Highbury groundsman, Bert Rudd, and with Bobby Daniel and Harry Ward, kicking a tennis ball about the passages, snack bars and empty terraces when we should have been assisting Rudd. It was easy to hide at Highbury: the place is colossal, as our groundsman boss discovered. Bert, incidentally, is still with Arsenal and we always have a chat when Sunderland play there. His usual greeting is, "Are you still managing to hide yourself?"

One of our hiding-places at Highbury was alongside the asphalt training pitch behind the terracing, and it was there that Bobby, Harry and I sat for hours watching the Arsenal stars train. My particular favourite was Eddie Hapgood, the finest left-back ever to play for England, and even during those not-so-serious antics on asphalt, Eddie seemed head and shoulders above all the other players. Hapgood had such tremendous faith in his own ability that his confidence affected everything he did, and it spread through any team in which he played.

Although I spent a complete season with Arsenal-from August 1938 to May 1939 - I turned out only twice in the famous red shirt, once against Oxford University and once against Bristol Rovers.

Quite a number of the Arsenal youngsters, myself included, were playing Athenian League football for Enfield: there were so many on the ground staff that it would have been impossible to give us all match practice with Arsenal, but, of course, each one kidded himself he was certain to get his chance one day.

Meanwhile I was being paid fifty shillings a week, twenty-seven and sixpence of which went on lodgings and laundry, and ten shillings home to Mum, so that by the time I had paid out a few coppers for odds and ends, I was left with the princely sum of ten shillings a week on which to live in London. It was enough in those days to supply my needs, an occasional evening at the pictures and a nightly dream of Shackleton shining in an Arsenal shirt-which cost me nothing.

Ground staff boys did not mix with the big men of Highbury. I seldom spoke to the Hapgoods, Swindins and Craystons, which is why I was staggered, in the course of a paddock-sweeping manoeuvre, to hear manager Allison shout, "Go and get stripped. I want you to play outside-left in the trial match." I did not wait to give him the chance of changing his mind: within five minutes I was in the dressing-room and out again, lining up at outside-left, a position I had never occupied before.

The opposing full-back was George Male, first choice for England; my partner was Gordon Bremner, a brilliant ball player who, but for the war, might well have become the inside-left for whom Arsenal had been searching since the retirement of Alex James. My main worry was a "doubtful" left foot, or, to be more truthful, a practically useless one.

Yes, in those days I was very much one-footed, in fact as a 5 feet 2 inches youngster, I don't think I had the strength to reach the penalty area from a corner kick using my good foot, never mind the left one. Things turned out better than I expected, a state of affairs entirely due to the brilliance of partner Gordon Bremner who, with the minimum of assistance from me, managed to `paralyze' the normally cool and capable George Male.

It was the only occasion during my 10 months at Highbury that I was able to play football with the stars there.

A week or two before the end of the season, Harry Ward and I were approached by groundsman Rudd and told, "The boss wants to see you in his office." We imagined the summons was in connection with some neglect of our ground staff duties: we both hoped it would not be a reprimand relating to the playing side of the job.

In the magnificent managerial mausoleum I stood awkwardly facing Mr Allison, wishing, I don't know why, that the pile on the ankle-deep carpet might grow and keep on growing until it attained a height of 5 feet 2 inches to hide me from the eyes of my manager.

Then followed an interview I shall never forget. With each pronouncement the facts became clearer. I was washed up, was not good enough for the Arsenal - or any other club for that matter; I would have to return to Bradford and become, perhaps, a miner, an engineer, perhaps a commercial traveller - but never a footballer.

Mr Allison could not have been kinder: he handled that interview with diplomacy, repeatedly assuring me that he was advising me in my own interests, and told me not to take the news too badly. One day I would be grateful. He said, "Go back to Bradford and get a job. You will never make the grade as a professional footballer." I should have been thankful to have discovered such shortcomings so early in my career, but my only thoughts that day were the shame of returning home a failure, the epitome of "local boy doesn't make good", and I was not far from tears as Allison's verdict was pronounced.

(3) Len Shackleton, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955)

I inquired if there was no alternative, and was told I could state a preference for coal mining. Deciding that, in the pit, I would at least be fairly near home-and Park Avenue football ground-I said I would have a crack at it. My papers to report as a Bevin Boy duly arrived, even though I had warned the postman not to worry if he accidentally mislaid an OHMS envelope addressed to Len Shackleton.

Attempting to look the part, even though I did not feel much like a pitman, I tried on the necessary equipment, overalls, boots, helmet, and even remembered to carry a lamp. Everything fitted perfectly, and I set off for the thirty-odd mile journey from Bradford to Fryston Colliery, near Castleford ... with team-mate Jimmy Stephen keeping me company.

I thought it was a severe enough shock having to leave home at six o'clock in the morning, but that was nothing compared to the experience of my first descent in the pit cage. For the benefit of anyone who has not travelled in one of those torture boxes, let me make it quite clear that a pit cage is nothing like a department store lift, although it is rumoured the same principle of operation is employed.

Going down in a pit cage is a terrifying experience: it is like being suspended on a piece of elastic. One minute you are rushing into the bowels of the earth, imagining Brisbane to be the next stop; the next minute you stop suddenly and ... just dangle. One day at Fryston was sufficient to convince me I had made a real blunder by volunteering for mining.

(4) Jackie Milburn, Jackie Milburn's Newcastle United Scrapbook (1981)

Newcastle United made a few astute buys at the end of the war including Len Shackleton from Bradford for £13,000. At the time I was a fitter at Hazelrigg Colliery and the club got Shackleton a job as my labourer... can you imagine that? It's hard to think of the highly skilled and artistic Shackleton being skivvy to anyone but these were difficult times and when it came to football we were still semi-pro.

We had a lot of fun together - I had a motor-bike even though they were banned by the club because they were too dangerous and we used to roar round the countryside on it thoroughly enjoying ourselves.

We even rode on the bike to St James's every Tuesday and Thursday morning for training, stashing it round the back out of sight and walking into the ground. If the club had known two such valuable assets were risking their necks at least twice a week they would have gone spare.

Shackleton never did anything by halves. On his debut against Newport County (a game we won 13 0) he scored six goals, a Division Two record, and put the last one in off his backside. Ever the showman, Shack always preferred to get applause for some daft trick rather than scoring a straight-forward goal.

(5) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

Len Shackleton, who was happy to be dubbed "The Clown Prince of Soccer" because of his extravagant and often eccentric behaviour on the field, had a superb game against the Germans but was never picked for England again. Len was unpredictable, brilliantly inconsistent, flamboyant, radical and mischievous; in short, he possessed all the attributes of a footballing genius which he undoubtedly was. But such a character would not go down well with the blazer brigade who ran English football and had such an important say in the selection of the England team."

(6) Len Shackleton, Crown Prince of Soccer (1955)

The professional footballer's contract is an evil document. Of that I am certain, so certain, in fact, that I am quite amazed that such a hopelessly one-sided document has survived the tremendous amount of criticism hurled at it by so many people in these enlightened days. Questions have been asked about it in the House of Commons. Public indignation has been voiced, yet the canker remains with us - causing unrest and dissatisfaction to spread through soccer, season after season.

We have often heard such words as serfs or slaves applied descriptively to footballers but until every player in the game has suffered soccer serfdom and raised his voice against it, I am afraid these descriptions will never be taken seriously. Let's face it - the average pro appears to have a pretty good life, with a possible £15 a week wage, plus bonuses, the hope of a £750 benefit (less tax) every five years, a nest egg of nine per cent of all his football earnings when he retires, a house in which to live, and a congenial working day.

That seems reasonable enough up to a point, but on closer examination many flaws may be spotted in the set-up. In the first place, no more than twenty-five per cent of League players draw the maximum £15 wage. Benefits are unheard of in many clubs, while in others they are halved, or even more drastically mutilated at the whim of the directors. Eviction from club houses is automatic when clubs decide to dispense with players' services, and the "pretty good life" is over usually long before a man's fortieth birthday-providing injury has not curtailed it even earlier. It was, in fact, stated once that the average playing life of a professional footballer is seven years, causing more than one of us to comment, "That's a career, that was."

Estimating the average retiring age at 35, the professional footballer finds himself, in the prime of life, jobless, homeless, with a few hundred pounds from the Benevolent Fund and no training for a trade or profession. He sometimes queues up for his turn on the guillotine of a managerial career, or for the menial duties of a team trainer, but there are obviously not enough jobs in football to accommodate every player wishing to stay in the game.

It is all very depressing to anyone hoping for security - and who does not? - but these are the sole "rewards" of the successful players; those who have remained free from injury and been permitted to serve their allotted span as good club servants.

What happens to the unlucky ones? The contract they sign when joining a League club ties them to that particular club for life, if that is the desire of the club, yet it can be terminated without notice if the manager or directors wish it. No more one-sided agreement was ever fashioned in the mind of man.

Professional players are no better than professional puppets, dancing on the end of elastic contracts held securely in the grip of their lords and masters. Sometimes the elastic is severed... always from above, never from below.

Assuming a player has good grounds for wanting a move from his club-his manager may have a particular grudge against him, he might have fallen out with his playing colleagues, or perhaps he detests the town in which he lives-he asks for a transfer. Then the fun starts.

The application may be treated favourably, to all intents and purposes, and the club agree to transfer the player to any other prepared to pay, say, £15,000 for him. To most, that figure is prohibitive, which means our disgruntled soccer star must stay put. On the other hand the Board Room verdict could be, "We are not parting with you," meaning, once again, that he stays where he is.

No other form of civil employment places such restrictions on the movements of individuals, while, at the same time, retaining the power to dismiss them summarily. If a man is able to better himself in a job elsewhere, he should be free to take that job on providing he has fulfilled his contract. It happens in every walk of life, but not in football. Tom Finney, Preston North End's international outside-right, was told he would be a rich man for life if he spent five years playing football on the Italian Riviera. Whether or not Tom was keen to accept this offer-made by an Italian prince - it would surely have been a waste of his time to consider it because Preston would hardly think of allowing him to say "Yes".

Another Italian club, Juventus, were anxious to sign the Teesside marvel, Wilf Mannion, and went so far as to propose to lodge £15,000 in Wilf's banking account on completion of the transfer. Mannion could not capitalize on his ability, because he was tied to Middlesbrough. I could have made a lot of money, much more than is dreamed of in English football, by joining a club in Turkey, but even after the expiry of my seasonal contract, I would not have been permitted to sample this particular Turkish delight.