Eddie Hapgood

Edris (Eddie) Hapgood was born in Bristol on 27th September 1908. After leaving school he worked as a milkman. He also played football for St. Phillip's Adult School Juniors. He was spotted by a director of Bristol Rovers and given a trial in a reserve match against Taunton United on May 7, 1927. He was offered a contract of £8 a week but he turned it down. Instead he signed for Kettering Town, who only paid him £4 a week but allowed him to carry on work as a milkman.

Hapgood continued to improve and in October 1927, Herbert Chapman signed him for a fee of £750. He only weighed 9 stones 6 pounds at the time and as Tom Whittaker, the Arsenal trainer, pointed out: "Hapgood used to cause a lot of worry by frequently being knocked out when heading the ball." Whittaker later recalled: "All sorts of reasons were propounded as to why this should happen, but eventually I spotted the cause. Eddie was too light, and we had to build him up. At that time he was a vegetarian, but I decided he should eat meat."

At this time the leather ball used in football got very heavy in wet weather. Headers had to be from the forehead. Anywhere else on the head, and even the strongest player could be knocked unconscious. One of the greatest headers of all time, Stan Cullis, suffered severe concussion on several occasions. Cullis, eventually was forced to retire after he was warned by a doctor that because of his previous head injuries, even heading a heavy leather football could prove fatal.

Hapgood joined a talented team that included players such as Alex James, David Jack, Jimmy Brain, Joe Hulme, Jack Lambert, Bob John, Jack Butler, Andy Neil, Jimmy Ramsey, Billy Blyth, Cliff Bastin, Herbert Roberts, Alf Baker and Tom Parker.

Hapgood made his debut against Birmingham City on 19th November 1927. It was not long before he was the club's regular left-back. As Jeff Harris pointed out in his book, Arsenal Who's Who: "Hapgood's many splendid attributes included, being technically exceptional, he showed shrewd anticipation and he was elegant, polished, unruffled and calm." Tom Whittaker added that: "Hapgood was an extraordinary youngster. Confident beyond his years, some people found him insufferable at times. But it was the supreme confidence in his own ability which made him such a great player."

In the 1929-30 season Arsenal finished in 14th place in the First Division. They did much better in the FA Cup. Arsenal beat Birmingham City (1-0), Middlesbrough (2-0), West Ham United (3-0) and Hull City (1-0) to reach the final against Chapman's old club, Huddersfield Town. Arsenal won the game 2-0 with goals from Alex James and Jack Lambert and Hapgood had his first cup winners' medal.

The following season Arsenal won their first ever First Division Championship with a record 66 points. The Gunners only lost four games that season. Jack Lambert was top-scorer with 38 goals.

Alex James was injured for a large part of the 1931-32 season and this was a major factor in Arsenal losing the title by two points to Everton. Arsenal won the First Division by four points in the 1932-33 season. Cliff Bastin was the club's top scorer with 33 goals. This was the highest total ever scored by a winger in a league season.

Hapgood won his first international cap for England against Italy on 13th May 1933. The game ended in a 1-1 draw but Hapgood was to remain a regular member of the team for the next six years. The England team at that time included Cliff Bastin, Wilf Copping, Albert Geldard, Eric Brook, Willie Hall, Sammy Crooks, Raich Carter, Frank Moss, Joe Hulme, Jackie Bray, George Camsell, Tom Cooper, Stanley Matthews, Fred Tilson, Cliff Britton, Ray Westwood, George Male, Frank Broome, Stan Cullis, Ted Drake, Len Goulden, Bert Sproston, Vic Woodley, Tommy Lawton and Alf Young.

When Tom Parker left Arsenal in 1933 Herbert Chapman appointed Hapgood as club captain. The following year he became captain of England. This included the match against Italy on 14th November 1934 where Hapgood suffered a broken nose.

Bob Wall, Arsenal's assistant manager, wrote in his autobiography, Arsenal from the Heart: "He (Hapgood) played his football in a calm, authoritative way and he would analyse a game in the same quiet, clear-cut manner. Eddie set Arsenal players the highest possible example in technical skill and personal behaviour."

Sunderland were the main challengers to Arsenal in the 1933-34 season thanks to a forward line that included Raich Carter, Patsy Gallacher, Bob Gurney and Jimmy Connor. In March 1934 Sunderland went a point ahead. However, the Gunners had games in hand and they clinched the league title with a 2-0 victory over Everton.

The following season Arsenal only finished in 6th place behind Sunderland. Arsenal did much better in the FA Cup that season. Arsenal beat Liverpool (2-0), Newcastle United (3-0), Barnsley (4-1) and Grimsby Town (1-0) to reach the final against Sheffield United. Ted Drake, who was not fully fit, scored the only goal of the final. Hapgood had won his second cup winners' medal.

Some of Arsenal's key players such as Cliff Bastin, Alex James, Joe Hulme, Bob John and Herbert Roberts were past their best. Ted Drake and Ray Bowden continued to suffer from injuries, whereas Frank Moss was forced to retire from the game. Given these problems Arsenal did well to finish in 3rd place in the 1936-37 season.

Before the start of the 1937-38 season Herbert Roberts, Bob John and Alex James retired from football. Joe Hume was out with a long-term back injury and Ray Bowden was sold to Newcastle United. However, a new group of younger players such as Bernard Joy, Alf Kirchen and Leslie Compton, became regulars in the side. George Hunt was also bought from Tottenham Hotspur to provide cover for Ted Drake who was still suffering from a knee injury. Eddie Hapgood, Cliff Bastin and George Male were now the only survivors of the team managed by Herbert Chapman.

Wolves were expected to be Arsenal's main rivals in the 1937-38 season. However, it was Brentford who led the table in February. They also beat Arsenal on 18th April, a game in which Ted Drake broke his wrist and suffered a bad head wound. However, it was the only two points they won during a eight game period and gradually dropped out of contention.

On the last day of the season Wolves were away to Sunderland. If Wolves won the game they would be champions, but they drew 1-1. Arsenal beat Bolton Wanderers at Highbury and won their fifth title in eight years. As a result of his many injuries, Ted Drake only played in 28 games but he still ended up the club's top scorer with 17 goals. This was Hapgood's 5th league championship medal.

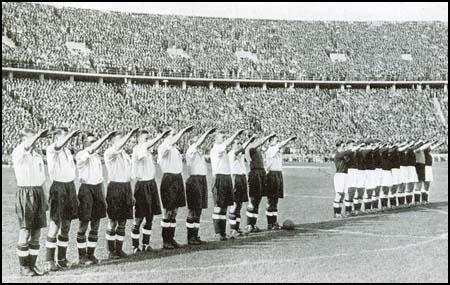

In May 1938 Hapgood was selected for the England tour of Europe. The first match was against Germany in Berlin. Adolf Hitler wanted to make use of this game as propaganda for his Nazi government. While the England players were getting changed an Football Association official went into their dressing-room and told them that they had to give the raised arm Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem. As Stanley Matthews later recalled: "The dressing room erupted. There was bedlam. All the England players were livid and totally opposed to this, myself included. Everyone was shouting at once. Eddie Hapgood, normally a respectful and devoted captain, wagged his finger at the official and told him what he could do with the Nazi salute, which involved putting it where the sun doesn't shine."

The FA official left only to return some minutes later saying he had a direct order from Sir Neville Henderson the British Ambassador in Berlin. The players were told that the political situation between Britain and Germany was now so sensitive that it needed "only a spark to set Europe alight". As a result the England team reluctantly agreed to give the Nazi salute.

The game was watched by 110,000 people as well as senior government figures such as Herman Goering and Joseph Goebbels. England won the game 6-3. This included a goal scored by Len Goulden that Stanley Matthews described as "the greatest goal I ever saw in football".

On Friday, 1st September, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. On Sunday 3rd September Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany. The government immediately imposed a ban on the assembly of crowds and as a result the Football League competition was brought to an end.

During the Second World War Hapgood served in the Royal Air Force. However, he did manage to play in over hundred friendly games between 1939 and 1945.

Hapgood returned to Arsenal after the war but he retired from playing in December 1945. During his time at the club he played in 434 league and cup games. He also made 30 appearances for England, most of these as captain. According to Tom Whittaker, the Arsenal trainer, during his career: "Hapgood got concussion three times, broke both ankles and broke his nose on three occasions."

In 1945 Hapgood published his autobiography, Football Ambassador. He also became manager of Blackburn Rovers but after the club finished in 17th place in the 1946-47 season he resigned. Hapgood then managed Watford in the Third Division South. After two unsuccessful seasons he left in 1950. He also took charge of Bath City between 1950 and 1956.

After losing his job at Bath he had some financial difficulties. Hapgood wrote to the Arsenal asking if he could have the testimonial match he did not have as a player. The club refused but did send him a cheque for £30. Hapgood also ran a YMCA at Harwell and Weymouth.

Eddie Hapgood died in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, on 20th April 1973. He was 64 years old.

Primary Sources

(1) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

I played little football at school. To be exact, only two games. Toward the end of my stay at the council school, efforts were being made to introduce more P.T. into the school curriculum. Football was also to be incorporated, so the headmaster told me to get a team together, and he fixed us up with clobber. We only played two matches, before I moved on to a higher grade school!

So it wasn't until I had finished school some years and had gone out into the world to earn my living, which consisted of driving a milk cart for my brother-in-law, who had a dairy near Bristol, that I took the game seriously. Then I got the bug and whipped up my old horse every Saturday morning to get away for a game with a local club, St. Phillip's Adult School Juniors. Mostly I played full-back, but on one occasion went centre-forward in the second-half and scored four goals in ten minutes!

(2) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

After a dozen games, Bill Collier, the Kettering manager, called me into his office and introduced me to a chubby man in tweeds, whose spectacles failed to hide the shrewd, appraising look from his blue eyes. I didn't know it then, but I was to see this man many times before he died so tragically seven years later.

"Eddie, this is Mr. Herbert Chapman, the Arsenal manager," said Bill Collier. "And the other gentleman is Mr. George Allison." And so I met two of the men who were to play such a major part in my future football career.

Herbert Chapman didn't say anything for a few seconds, then shot out, " Well, young man, do you smoke or drink ?" Rather startled, I said, "No, sir." "Good," he answered. " Would you like to sign for Arsenal!" Would I. I could hardly set pen to paper fast enough. I believe Mr. Chapman paid Kettering roughly £1,000 for my transfer - £750 down and a guarantee of about £200 for a friendly match later on. But I didn't worry about that at the time.

That remark of Mr. Chapman's about smoking and drinking impressed itself on my mind, for I have never done either during my career, with the exception of drinking occasional toasts at banquets and other functions.

(3) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

Herbert Chapman was a great planner who loved to sit up to the early hours with Tom Whittaker and, perhaps, a newspaperman or two, arguing tactics, angles, theories; whose first thought was for the players - "if they are settled then I can be comfortable too" was his code; who never made a bad "buy"; who could not tolerate dirty play or slacking - the man who made Arsenal.

Herbert, in his early days a professional footballer, loved the game and understood it as well as anybody. He never forgot his first connection with the game, and, although his main interest was to give bigger and better football to the public, he always had a soft spot for the pro.

His death in 1934 left a gap which, to my mind, has never been adequately filled. I shall long remember that day. We were due to play Sheffield Wednesday at Highbury. I was shaving at my Finchley home when Alice Moss, wife of our goalkeeper, came rushing in in an awful state. While shopping she had seen the placards which shrieked to the world "Herbert Chapman Dead." I still had one side of my face lathered, and so stunned was I by the news that I stayed that way for quite fifteen minutes. Then I finished my shave and hurried along to the ground to find the news was only too true. Highbury backstage was like a morgue that afternoon and we weren't very keen on the job of playing football.

It was a long time before we recovered from that tragic day. Herbert Chapman, the man who had done so much, and who still had so much to do. We may never see his like again. As I have already said, when Mr. Chapman went, Tom Whittaker tried to fill the gap for us. Tom is a great lad and a gentleman. He looked after us as if we were a flock of unruly sheep. Even Alex James was less boisterous when Tom was around.

Looking back, I realise I must have been a difficult customer for Tom. I rarely trained with the other lads, preferring to slog away by myself. It was not that I didn't get on with the rest of the players, or thought that I knew more than Tom could teach me, but I felt I knew just how far I could go when I was training myself. Often I trained in the empty stadium. If ever there's a ghost at Highbury, he'll probably look like me.

Tom used to let me go my own sweet way. I'm glad he had that trust in me. I was always training. One of my favourite tricks was to take a ball over the railings on the terracing, bang it up the slope and intercept it as it came bobbing down, cannoning off railings and the wooden piles. Surprising how helpful this became-but be careful of your ankles if you try it.

Tom always says I'm the toughest player he ever met. When I first arrived at Highbury I weighed only nine stone, six pounds. I was probably the lightest full-back on the books of a league club at the time....

About this time I was causing a lot of worry to the club by frequently being knocked unconscious while heading the ball, particularly on heavy grounds.

All sorts of reasons were put forward to answer this phenomenon-I even heard said that I had no bone on the top of my head-but Tom Whittaker found out what was wrong. "You're too light," he told me, " and we've got to build you up." At that time I was a vegetarian and old Tom decided I'd got to eat meat. My first meat dish was a plate of thinly cut ham. I got that down and progressed by various stages until I was eating steaks as thick as Whitaker's Almanack.

(4) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

1929 was a year of destiny for Arsenal and myself. In that year the foundations were laid of the mighty side which was to sweep everything before it, and which was to become the greatest club side soccer history has known.

During the season which ended in April 1929, 1 had finally clinched my place in the Arsenal first team, while Herbert Roberts, Charlie Jones and Jack Lambert had also made their appearance. During the following summer, Herbert Chapman made two of his greatest buys, to change, materially, the fortunes of our club.

He signed Alexander James and Clifford Sydney Bastin.

James was 28 and brought, from Preston, a reputation 'which cost Arsenal £9,000; Bastin was barely seventeen and had been a professional footballer a matter of weeks. What a contrast - and what a wing.

Brought together from clubs as far apart as Preston and Exeter; one a tough little Scot from Bellshill, hard as a nut, commercially-minded, determined to get much out of football, who had joined Arsenal because it offered the best possibilities of improving his position; the other, the son of sturdy West Country folk, who was born to be great, quiet, reserved, but, even then, with the infinite ability of being able to play football with the touch of the master . . their destinies were irretrievably interwoven. The James-Bastin wing was a natural.

(5) Tom Whittaker, The Arsenal Story (1957)

Hapgood used to cause a lot of worry by frequently being knocked out when heading the ball.... All sorts of reasons were propounded as to why this should happen, but eventually I spotted the cause. Eddie was too light, and we had to build him up. At that time he was a vegetarian, but I decided he should eat meat.

(6) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

My greatest Cup Final thrill was my first in 1930, I had only been in the Arsenal first team little over a year. We beat mighty Huddersfield that day, a great win, and a great moment for the Old Boss, who had made Huddersfield into a wonderful side, and who had then come on to make us an even greater team. That was the start of our great run. In the next eight years we won the League five times, were runners-up once and finished third on another occasion. We also won the Cup and were beaten in the Final.

There was a lot of newspaper criticism about our first goal. One school of thought had it that Alex James committed an infringement when scoring. Others argued that it was quite legal. We of the Arsenal contended then, and I do so now, that it was fair. And a conversation I had with Tom Crew, who refereed the game, some time later, bears out that contention.

Alex was fouled somewhere near the penalty area, and, almost before the ball had stopped rolling, had taken the free-kick. He sent a short pass to Cliff Bastin, moved into position to take a perfect return, and banged the ball into the Huddersfield net for the all-important first goal. Tom Crew told me that James made a silent appeal for permission to take the kick, and he waved him on. It was one of the smartest moves ever made in a big match and it gave us the Cup. I contend that it was fair tactics; for if Alex had waited a few seconds for the whistle, the Huddersfield defence would have been in position, and the advantage of the free-kick would have been lost. Jack Lambert got the second goal late in the second half, also from a move by Alex.

(7) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

The game got under way and from the very first tackles, I was left in no doubt that this was going to be a rough house of a game. I wasn't wrong. After a challenge between Drake and Monti, the Italian had to leave the pitch with a broken foot after only two minutes. This only made matters worse. For the first quarter of an hour there might just as well have not been a ball on the pitch as far as the Italians were concerned. They were like men possessed, kicking anything and everything that moved bar the referee. The game degenerated into nothing short of a brawl and it disgusted me...

Ted Drake latched on to an ale-house long ball out of defence and broke away to score a wonderful individual goal on his international debut. He paid for it. Minutes after the game re-started I watched in sadness as Ted was carried from the field, tears in his eyes, his left sock torn apart to reveal a gushing wound.

I thought the three quick goals would calm the Italians down, showing them that rough-house play didn't pay dividends, but they got worse. I felt it was a great shame they had adopted such tactics because individually they were very talented players with terrific on-the-ball skills. They didn't have to resort to rough-house play to win games. Why they had done so this day was beyond me.

Not long after Eric Brook had put us two up, Bertolini hit Eddie Hapgood a savage blow in the face with his elbow as he walked past him. Eddie fell like a Wall Street price in 1929. The next few minutes were dreadful. Tempers flared on both sides, there was a lot of pushing and jostling and punches were exchanged. I abhor such behaviour on the field and when I saw Eddie Hapgood being led off with blood streaming down his face from a broken nose, it sickened me. I'd been really keyed up and looking forward to showing what I could do on the big international scene, but this game was turning into a nightmare.

The game got under way again and the Italians continued where they had left off. It got to a few of our players and I don't mind saying it affected me. Fortunately, we had two real hard nuts in the England side that day in Eric Brook and Wilf Copping who started to dish out as good as they got and more. Wilf was an iron man of a half-back, a Geordie who didn't shave for three days preceding a game because he felt it made him look mean and hard. It did and he was. Eric Brook received a nasty shoulder injury and continued to play manfully with his shoulder strapped up. He was in obvious pain but he just carried on, seemingly ignoring it.

Just before half-time, Wilf Copping hit the Italian captain Monti with a tackle that he seemed to launch from some¬where just north of Leeds. Monti went up in the air like a rocket and down like a bag of hammers and had to leave the field with a splintered bone in his foot. Italy were starting to get the upper hand and laid siege to our goal. It was desperate stuff.

Our dressing room at half-time resembled a field hospital. We were 3-0 up but had paid a bruising price. No one had failed to pick up an injury of one sort of another. The language and comments coming from my England team-mates made my hair stand on end. I was still only 19 but came to the conclusion I'd been leading a sheltered life. I was relieved when our team trainer came into the dressing room, calmed everyone down and said that under no circumstances were we to copy the Italian tactics. We were to go out, he said, and play the way every English team had been taught to play. To do anything but, he said, would exacerbate the situation. Exacerbate the situation? It was already a bloodbath.

(8) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

The game against Germany took on a significance far beyond football. The Nazi propaganda machine saw it as an opportunity to display Third Reich superiority and played up that disconcerting theme big style in the German newspapers. The German team had spent ten days preparing for the game at a special training centre in the Black Forest, whereas after a long and tiresome train journey, we had less than two days to prepare for what we knew was going to be a game of truly epic proportions, a game which to this day is looked upon as the most infamous game England have ever been involved in and all due to one incident.

After all this time, and once and for all, I would like to set the record straight about that incident. As the players were getting changed, an FA official came into our dressing room and informed us that when our national anthem was played, the German team would salute as a mark of respect.

The FA wanted us to reciprocate by giving the raised arm Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem. The dressing room erupted. There was bedlam. All the England players were livid and totally opposed to this, myself included. Everyone was shouting at once. Eddie Hapgood, normally a respectful and devoted captain, wagged his finger at the official and told him what he could do with the Nazi salute, which involved putting it where the sun doesn't shine. In fact, Eddie went so far as to offer a compromise, saying we would stand to attention military style but the offer fell on deaf ears.

I sat there crestfallen, thinking what on earth my family and the people back home would think if they saw me and the rest of the England team paying lip service, so to speak, to the Nazi regime and its leaders.

The beleaguered FA official left only to return some minutes later saying he had a direct order from Sir Neville Henderson the British Ambassador in Berlin that had been endorsed by the FA secretary Stanley Rous. We were told that the political situation between Great Britain and Germany was now so sensitive that it needed "only a spark to set Europe alight". Faced with the knowledge of the direst consequences, we felt we had little choice in the matter and reluctantly agreed to the request. However, the game was different. We knew we had it in our power to do something about the match itself and to a man we took the field determined to do so.

All of 110,000 people were crammed into the Olympic Stadium, including Goering and Goebbels, and they roared their approval as the German team took the field. If ever men in the cause of sport felt isolated and so very far from their homes, it was the England team that day in Berlin. The Olympic Stadium was draped in red, black and white swastikas with a large portrait of Hitler above the stand where the Nazi leaders and dignitaries sat. It seemed every supporter on the massed terraces had a smaller version of the swastika and they held them aloft in a silent show of collective defiance as the England team ran out.

During the pre-match kick-in, I went behind our goal to retrieve a wayward ball and an amazing thing happened. As I curled my foot around the ball to steer it back towards the pitch, two lone voices called out, "Let them have it, Stan. Come on England!"

I scanned the sea of faces and the hundreds of swastikas before I saw the most uplifting sight I have ever seen at a football ground. There, right at the front of the terracing, were two Englishmen who had draped a small Union Jack over the perimeter fencing in front of them. Whether they were civil servants from the British Embassy, on holiday or what I don't know, but the brave and uplifting words of those two solitary English supporters among 110,000 Nazis had a profound effect on me and the rest of the England team that day.

When I got back on to the pitch I pointed out the two supporters to our captain Eddie Hapgood and the word spread throughout the team. We all looked across to these two doughty men, who responded by raising the thumbs of their right hands in encouragement. As a team we were immediately galvanised, determined and uplifted by the courage of these two supporters and their small Union Jack Up to that point, I had never given much thought to our national flag. That afternoon however, small as that particular version was, it took on the greatest of symbolism for me and my England team-mates. It seemed to stand for everything we believed in, everything we had left behind in England and wanted to preserve. Above all, it reminded me that we were not after all alone.

The photograph of the England team giving the Nazi salute appeared in newspapers throughout the world the next day to the eternal shame of every player and Britain as a whole. But look closely at the photograph and you will see the German team looking straight ahead but the England players looking off to their left. I can tell you that all our eyes were fixed upon that Union Jack from which we were drawing the inspiration that would carry us to a fantastic and memorable victory.

(9) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

Away we went, and, in fifteen minutes, had the match (apparently) well won. Inside thirty seconds we should have been one up, but Eric Brook's penalty effort was magnificently saved by Ceresoli, the Italian goalkeeper, and a very good one, too. But Eric made up for that. After nine minutes, he headed a cross from Matthews into the net, and, two minutes later, smashed in a second goal from a terrific free kick, taken just outside the penalty area.

Our lads were playing glorious football and the Italians, by this time, were beginning to lose their tempers. Barely had the cheers died down from the 50,000 crowd, than I ran into trouble. The ball went into touch on my side of the field, and, to save time, the Italian right-winger threw the ball in. It went high over me, and, as I doubled back to collar it, the right-half, without making any effort whatsoever to get the ball, jumped up in front of me and carefully smashed his elbow into my face.

I recovered in the dressing-room, with the faint roar from the crowd greeting our third goal (Drake), ringing in my ears, and old Tom working on my gory face. I asked him if my nose was broken, and he, busily putting felt supports on either side, and strapping plaster or, said it was. As soon as he had finished his ministrations, I jumped up and ran out on to the field again.

There was a regular battle going on, each side being a man short - Monti had also left the field after stubbing his toe and breaking a small bone in his foot. The Italians had gone beserk, and were kicking everybody and everything in sight. My injury had, apparently, started the fracas, and, although our lads were trying to keep their tempers, it's a bit hard to play like a gentleman when somebody' closely resembling an enthusiastic member of the Mafia is wiping his studs down your legs, or kicking you up in the air from behind.

Wilf Copping enjoyed himself that afternoon. For the first time in their lives the Italians were given a sample of real honest shoulder charging, and Wilf's famous double-footed tackle was causing them furiously to think.

The Italians had the better of the second half, and, but for herculean efforts by our defence, might have drawn, or even won, the match. Meazza scored two fine goals in two minutes midway through the half, and only Moss's catlike agility kept him from securing his hat-trick and the equaliser. And we held out, with the Italians getting wilder and dirtier every minute and the crowd getting more incensed. One of the newspaper men was so disgusted with the display that he signed his story "By Our War Correspondent."

The England dressing-room after the match looked like a casualty clearing station. Eric Brook (who had had his elbow strapped up on the field) and I were packed off to the Royal Northern Hospital for treatment, while Drake, who had been severely buffeted, and once struck in the face, Bastin and Bowden were patients in Tom Whittaker's surgery.

(10) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

The story starts in 1936. That year England competed in the Berlin Olympic Games, held in the fabulous stadium, built for the sole purpose of impressing the world with Nazi might-hundreds of millions of marks were spent, not only in the building, but in propaganda to put over the Games.

Mr. Stanley Rous, the Football Association secretary, went over in charge of the English amateur side, which competed in the soccer tournament. Early on, the question of the salute to be given Hitler at the march-past was causing some anxiety. After most of the other countries had decided on the Olympic salute (which is given with the right arm flung sideways, not forward and upward like the Nazi salute), it was arranged that the English athletes should give only the 'eyes right.' Mr. Rous told me afterwards that, to Hitler, and the crowd stepped up in masses round him, the turning of the head by the English team probably passed unnoticed after the outflung arms of the other athletes. So much so that the crowd booed our lads, among them Arsenal colleague, Bernard Joy, and everyone seemed highly offended.

When it was our turn to come into the limelight two years later over the same vexed question of the salute, Mr. Wreford Brown, the member in charge of the England team and Mr. Rous, sought guidance from Sir Nevile Henderson, the British Ambassador to Germany, when our party arrived in Berlin. Mr. Rous reminded Sir Nevile of his previous experience and suggested, as an act of courtesy, but what was more important, in order to get the crowd in a good temper, the team should give the salute of Germany before the start. Sir Nevile, vastly relieved at the readiness of the F.A. officials to help him in what must have been an extremely difficult situation, gladly agreed it was the wisest course.

Mr. Wreford Brown and Mr. Rous came back from the Embassy, called me in (I was captain) and explained what they thought the team should do. I replied, "We are of the British Empire and I do not see any reason why we should give the Nazi salute; they should understand that we always stand to attention for every National Anthem. We have never done it before-we have always stood to attention, but we will do everything to beat them fairly and squarely." I then went out to see the rest of the players to tell them what was in the offing. There was much muttering in the ranks.

When we were all together a few hours before the game, Mr. Wreford Brown informed the lads what I had already passed on. He added that as there were undercurrents of which we knew nothing, and it was virtually out of his hands and a matter for the politicians rather than the sportsmen, it had been agreed that to give the salute was the wisest course. Privately he told us that he and Mr. Rous felt as sick as we did, but that, under the circumstances, it was the correct thing to do.

Well, that was that, and we were all pretty miserable about it. Personally, I felt a fool heiling Hitler, but Mr. Rous's diplomacy worked, for we went out determined to beat the Germans. And after our salute had been received with tremendous enthusiasm, we settled down to do just that. The only humorous thing about the whole affair was that while we gave the salute only one way, the German team gave it to the four corners of the ground.

The sequel came at the dinner in the evening after the game, given by the Reich Association of Physical Exercises, when, with everybody in high good humour, Sir Nevile Henderson whispered to Mr. Rous, " You and the players proved yourselves to be good Ambassadors after all !"

(11) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955)

Among the full backs, Eddie Hapgood was a classic. He was a real football enthusiast, and never tired either of talking about the game or of playing it. His creed was that a good footballer should obtain the maximum advantage from the minimum effort, and Eddie certainly practised what he preached. His positional play and his ball control was an object lesson to every youngster.

Eddie was also a great captain - and there are few great captains around these days. He was a stickler for discipline, he was hard, he was a driver ... but isn't that what you want in a skipper? Some of his pre-match pep talks should have been recorded. They would have been real eye, or ear, openers!

Coming to the wing halves, who can ever forget the Iron Man - Wilf Copping. Wilf could take and give knocks as hard as anyone, but he was also a footballer, the sort of man it was nicer to see with you than against you!

(12) Brian Glanville, Sports Star (16th December, 2006)

When Allison finally resigned in 1947, Whittaker was a natural choice to take over and in his first managerial years he had much success, instantly winning the first division title, after a parlous 1946/47 season for the club in which at one time relegation loomed. In 1950 the Gunners won the FA Cup for the first time since 1936.

Yet there was another less positive side to Whittaker and I encountered it as a 19-year-old journalist in 1951. I'd written or rather "ghosted" my first book, Cliff Bastin Remembers, the autobiography of one of the foremost Arsenal stars, supreme goal-scorer and left-winger, of the inter-War years. Tom had supplied the foreword. To my surprise, since I had simply put down exactly what Bastin in his forthright way thought, the book proved controversial and had extensive newspaper and magazine coverage. Going to Highbury to interview Whittaker, I was surprised, when I asked him what he thought of the book, to be told that he had never seen it: "I believe Cliff brought a couple of copies to the ground."

When the publishers heard this they were incensed; they'd given Cliff, they told me, special early copies; and they wrote to rebuke him. In return they had a letter rebuking me for telling them things untrue. I myself wrote to Cliff fully accepting his explanation and got a letter, my last ever from him, saying he quite understood my good faith; but he had heard Whittaker had said he wished he had never written the foreword. His final sentence read: "But in future, watch your step at Highbury." Whittaker had lied.

Far more serious was the Eddie Hapgood affair. Eddie, left-back and captain of pre-War Arsenal, had been my own particular hero. He himself had idolised Whittaker. In 1969 there appeared a book called Arsenal from the Heart by Bob Wall, who had crawled his way up from being Chapman's office boy to chief executive. The book alleged that at the end of the War, Hapgood and the former right-half and future Gunners' Manager "Gentleman" Jack Crayston had demanded benefit payments, been refused and had appealed unsuccessfully to the Football League. Then, when Arsenal, in better financial shape, had offered them the money, they had turned it down. Wall should have smelt a rat immediately. Such benefit payments, some £750 for each five years' of service, were purely optional, at the clubs' discretion. As luck had it, I was then due to go down to Weymouth in south west England to interview Eddie for a television programme I was making for the BBC series, One Pair Of Eyes. He was then in charge of a hostel for apprentices of the Atomic Agency. When I told him this tale he was horrified, and produced a folder of correspondence with Arsenal. Having lost his last managerial job at little Bath City, he had written to Arsenal asking for help, as he had never had a benefit. They sent him £30!

I told Wall of this and also told him that the Football League had no record of any such appeal. Where had he got the story? Answer: from Tom Whittaker! Was this because Whittaker, hoping to manage Arsenal, had feared opposition from Hapgood, whose reputation was still then so large? I asked to see the club's minutes. "The chairman wouldn't like it," countered Wall. "You can write whatever you like, Brian, and Arsenal will not reply." I did and they didn't.