Preston North End: 1862-1945

Preston North End were founded as a cricket club in 1862. Their original name was Preston Nelson but later changed it to reflect the fact that they played their games in Ashton, at the north end of Preston.

In 1875 Preston North End began playing their games on land at Deepdale Farm. They also formed a rugby team at this time. Later, they established a football team that played its games at Deepdale.

On 5th October 1878, Preston North End played its first football game. Eagley beat them 1-0. Two years later the club decided to concentrate on football rather than cricket or rugby.

Major William Sudell, the manager of a local factory, became the secretary of Preston North End. Sudell decided to improve the quality of the team by importing top players from other areas. This included several players from Scotland joined the club. Over the next few years players such as John Goodall, Jimmy Ross, Nick Ross, David Russell, John Gordon, John Graham, Robert Mills-Roberts, James Trainer, Samuel Thompson and George Drummond. He also recruited some outstanding local players, including Bob Holmes, Robert Howarth and Fred Dewhurst. As well as paying them money for playing for the team, Sudell also found them highly paid work in Preston.

In January, 1884, Preston North End played the London side, Upton Park, in the FA Cup. After the game Upton Park complained to the Football Association that Preston was a professional, rather than an amateur team. Sudell admitted that his players were being paid but argued that this was common practice and did not breach regulations. However, the FA disagreed and expelled them from the competition.

Preston North End now joined forces with other clubs who were paying their players, such as Aston Villa and Sunderland. In October, 1884, these clubs threatened to form a break-away British Football Association. The Football Association responded by establishing a sub-committee, which included Sudell, to look into this issue. On 20th July, 1885, the FA announced that it was "in the interests of Association Football, to legalise the employment of professional football players, but only under certain restrictions". Clubs were allowed to pay players provided that they had either been born or had lived for two years within a six-mile radius of the ground.

In 1886 Major William Sudell signed Arthur Wharton, who had recently set a new world record when he ran the 100 yards at Stamford Bridge in 10 seconds. Despite his tremendous speed he played in goal. Wharton was the first black man to play professional football in England. In 1887 Walton played against West Bromwich Albion in the FA Cup semi-final but lost 3-1.

Under the leadership of Major William Sudell, Preston North End became one of the best clubs in England. In the first round of the FA Cup in 1887-88, Preston beat Hyde 26-0. This is the highest score ever recorded in the competition. Jimmy Ross, who had developed a good partnership with centre-forward John Goodall, scored seven of the goals against Hyde.

Preston played West Bromwich Albion in the final that year. According to reports, Preston was much the better team and Bob Roberts, the WBA goalkeeper made good saves from Fred Dewhurst, Jimmy Ross, John Goodall and George Drummond. Dewhurst did eventually score but WBA won the game 3-1.

In March, 1888, William McGregor, a director of Aston Villa, circulated a letter suggesting that "ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England combine to arrange home and away fixtures each season." The following month the Football League was formed. It consisted of six clubs from Lancashire (Preston North End, Accrington, Blackburn Rovers, Burnley and Everton) and six from the Midlands (Aston Villa, Derby County, Notts County, Stoke, West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers). The main reason Sunderland was excluded was because the other clubs in the league objected to the costs of travelling to the North-East.

The first season of the Football League began in September, 1888. Over 6,000 people turned up to Deepdale to see Preston play the first game against Burnley. Preston's Fred Dewhurst scored a goal after only two minutes. Samuel Thompson put them two-up after five minutes and they went onto win the game 5-2.

Preston North End won the first championship that year without losing a single match and acquired the name the "Invincibles". Eighteen wins and four draws gave them a 11 point lead at the top of the table. The top goal scorers were John Goodall (21), Jimmy Ross (18), Fred Dewhurst (12) and John Gordon (10).

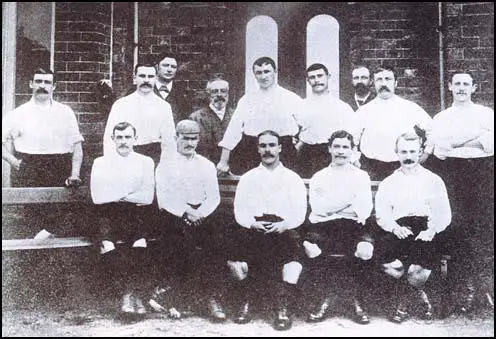

Bob Holmes, Robert Howarth, William Sudell, John Graham and Robert Mills-Roberts are in the

back row. John Gordon, Jimmy Ross, John Goodall, Fred Dewhurst and Samuel Thompson

are sitting on the bench.

Preston also beat Wolverhampton Wanderers 3-0 to win the 1889 FA Cup Final. The goals were scored by Jimmy Ross, Fred Dewhurst and Samuel Thompson. Preston won the competition without conceding a single goal.

John Goodall, Bob Holmes, Robert Howarth and Fred Dewhurst all went onto play for England, whereas Robert Mills-Roberts and James Trainer played for Wales. However, the heart of the team was made up of the Scotsmen, Jimmy Ross, Nick Ross, David Russell, John Gordon, and George Drummond.

Preston North End also won the league the following season. This time it was much closer as they only beat Everton by one point. James Trainer, John Gordon and David Russell appeared in all 22 league games and Jimmy Ross and George Drummond only missed one game.

It was the last time that Preston was to win the Football League. They finished second to Everton (1890-91) and Sunderland (1892-93) but after that they ceased to become a major force in the game. Preston's top players were persuaded to sign for other clubs. This included John Goodall (Derby County), Jimmy Ross (Liverpool), David Russell (Nottingham Forest) and Samuel Thompson (Wolves). Whereas Bob Holmes, George Drummond, Nick Ross, Robert Mills-Roberts, James Trainer and John Graham retired from full-time professional football.

In 1893-94 Preston finished third from bottom (14th). That season William Sudell was sent to prison for embezzling £5,000 from his employers. Preston continued to struggle and finished 15th in 1898-99 and 16th in 1899-1900.

On 20th March, 1901, Preston's excellent goalkeeper, Peter McBride injured a shoulder in a trial for the Scottish team. As a result McBride missed the last five games of the season. His deputy let in 15 goals in those games and Preston was relegated from the First Division.

Preston North End began a period of rebuilding. Robert Jack, who had been a great success with Bolton Wanderers joined in 1901. Richard Bond was signed from the Royal Field Artillery in 1902. Bond, fast and direct outside right, eventually played for England. The international goalkeeper Fred Griffiths also joined in 1902 as a replacement for Peter McBride, who broke his collarbone during a match against Middlesbrough. In 1903 the club signed John Bell from Everton. Although now 34 years old, Bell was an experienced Scottish international.

John Bell formed a great partnership with Richard Bond. The two men played an important role in getting Preston promoted to the First Division of the Football League in their first season together. That year Preston won the Second Division title by winning 20, and drawing 10, of its 34 games. Peter McBride had a great season, keeping 14 clean sheets.

Preston North End managed a respectable 8th place in the 1904-05 season. The following season, Preston finished second to Liverpool. Goalkeeper, Peter McBride, had another great season and the team had the best defensive record in the First Division. The 36 year old John Bell also had a great year and Richard Bond was top scorer with 17 goals.

After John Bell and Richard Bond left the club, the best player at Preston was Joseph McCall. He was fairly short for a centre-half (5ft 8in). However, he made up for this deficiency with other talents. McCall was a great organizer and leader of men and the Preston manager, Charlie Parker, appointed him captain. McCall also became a regular member of the England team.

In 1909 Preston North End signed Jimmy Bannister who had won a First Division championship medal with Manchester United. However, he was not a great success and he only scored 12 goals in 65 games

With Peter McBride in goal and Joseph McCall at centre-half, Preston had a good defensive record. However, the club had difficulty scoring goals and at the end of the 1911-12 season, was relegated from the First Division of the Football League.

Alf Common, the former English international, was purchased from Arsenal for £250, half-way through the 1912-13 season. Common scored 7 goals in 21 games and helped Preston win the Second Division title with 53 points. Common also scored against Sunderland on the opening day of the 1913-14 season. He was now 33 years old and only played in 13 more games before retiring from football. Preston finished in 19th place in the 1913-14 season and were relegated once again. Freddie Osborn ended up as top scorer with 26 goals.

Preston finished second to Derby County in the final season before the First World War. One again Freddie Osborn was top scorer. This time he scored 17 goals. However, the club had to wait another four years before they could take their place in the First Division.

The records are incomplete but it is known that at least three Preston players, Fred Griffiths, John Barbour and William Gerrish were killed on the Western Front during the war. Richard Bond was taken prisoner by the German Army and William Luke was so badly wounded his football career came to an end.

Freddie Osborn, Preston's leading scorer in the 1913-14 and 1914-15 seasons, joined the 160th Brigade Royal Field Artillery (RFA). He served on the Western Front and in 1918 he was badly wounded by a bullet that hit him in the thigh.

Dick Kerr Ladies emerged as the best woman's football team during the First World War. Several members of the Preston North End team helped with the coaching. This included Bob Holmes, John Morley, Billy Greer and Jack Warner.

During the war Charlie Parker worked for the civil service as an accountant. When the Football League resumed in 1919, Vincent Hayes was appointed manager of the club. Hayes first task was to replace leading goalscorer Freddie Osborn, whose wartime injury had made him unavailable for selection. Later that year Hayes signed Tommy Roberts from Leicester Fosse and Rowland Woodhouse from Lancaster Town.

Over the next two years Vincent Hayes brought in the much travelled Archie Rawlings and the English international winger, Alf Quantrill. Woodhouse, Rawlings and Quantrill provided the service for Roberts who was the club's top scorer for the next five seasons: 1919-20 (29), 1920-21 (25), 1921-22 (25), 1922-23 (29) and 1923-24 (26).

Vincent Hayes also tried to improve the quality of Preston's defence. Joseph McCall, despite his advancing age, was still playing at centre-half. Hayes purchased full-back George Speak from West Ham United and wing-half George Waddell from Bradford City. Local youngster Billy Mercer was also drafted into the side.

Preston North End did very well in the FA Cup in 1921. The club defeated Newcastle United (3-1), Barnsley (3-0) and Arsenal (2-1). Archie Rawlings scored the first goal in the semi-final against Tottenham Hotspur and created the chance for Tommy Roberts to score the winning goal.

Preston played Huddersfield Town in the final. The team lost to the only goal of the game, a penalty conceded by Tommy Hamilton. It was awarded when Hamilton tripped Huddersfield's outside-left Billy Smith. Hamilton admitted the offence but claimed it was outside the penalty area.

Despite the goals from Tommy Roberts and the signing of English international, George Harrison, Preston continued to struggle in the league. The club finished 19th (1919-20), 16th (1920-21), 16th (1921-22), 16th (1922-23) and 18th (1923-24).

Jim Lawrence replaced Vincent Hayes at the end of the 1923-24 season. Lawrence had won three First Division championships and five FA Cup medals while playing in goal for Newcastle United. However, he had very little experience as a manager, having served for less than a season at South Shields. Preston was also undergoing a financial crisis and his first action was to sell the club's leading scorer, Tommy Roberts to Burnley. In the previous five seasons he had scored 118 goals in 199 games.

Lawrence signed veteran strike, Horace Barnes, from Manchester City in November, 1924. Rowland Woodhouse was asked to play in a deeper, midfield role, but still managed to score 9 goals that season. Barnes scored six in his first 10 games and finished as the club's joint top scorer in the league. Despite the goals of Woodhouse and Barnes, Preston finished in 21st place in the league and were relegated to the Second Division.

Jim Lawrence resigned and was replaced by Frank Richards, the former secretary/manager of Birmingham City. Richards brought in former Aston Villa and England international Harry Hampson as coach. Richards also arranged the transfer of Alex James and David Morris from Raith Rovers. James did well in his first season ending up as the club's top scorer with 14 league goals. He also won his first international cap when he played in Scotland's 3-0 victory over Wales in October, 1925. However, Preston only finished in 12th place and failed to get promotion to the First Division.

In the 1926-27 season Alex James developed a good partnership with centre-forward, Tommy Roberts, who had returned to the club after spending a couple of seasons at Burnley. Preston finished in 6th position in the 1926-27 season, with Roberts scoring 30 goals. This included all four in a 4-2 FA Cup victory at Lincoln City. Frank Richards was disappointed with his failure to achieve promotion and resigned from his post in 1927.

In 1927 Alex Gibson become manager of Preston North End. Soon after taking over the job he was forced to find a replacement for Tommy Roberts, who had been involved in a serious car accident. Norman Robson was promoted from the reserve team and managed to score 19 goals in 22 appearances. That year Preston scored 100 goals and finished in 4th position. Alex James was the star of the Preston side that season and attracted the notice of all the top clubs when he scored two spectacular goals in Scotland's 5-1 victory over England at Wembley on 31st March, 1928.

George Harrison was Preston's penalty taker and during his time at the club (1923-1931) he scored 33 out of 35. His method was to kick the ball as hard as possible at the centre of the goal. He argued that the goalkeeper would instinctively would go one way or the other and leave the middle of the goal undefended.

At the beginning of the the 1928-29 season, Alex Gibson persuaded the Partick Thistle striker, Alex Hair, to join the club. In his first season he scored 19 goals in 31 games. However, Preston only finished in 13th place of the Second Division.

Alex James was becoming frustrated with playing Second Division football. In four years at Preston he scored 55 goals in 157 appearance. He also supplied the passes that resulted in plenty of goals for his strike partners, Tommy Roberts, Norman Robson, George Harrison and Alex Hair.

James was also upset with Alex Gibson for not always releasing him to play international games for Scotland. Most of all, he was dissatisfied with his wages. At the time, the Football League operated a maximum wage of £8 a week. However, other clubs had found ways around this problem. This included Arsenal who signed James for £8,750 in 1929. Herbert Chapman, the manager of Arsenal, arranged for James to obtain a £250-a-year "sports demonstrator" job at Selfridges. It was also agreed that James would be paid for a weekly "ghosted" article for a London evening newspaper.

Alex Gibson was blamed for the loss of Alex James. Others said that if he had to go, Gibson should have got a better price for the man considered to be the best player in the Football League. The main complaint against Gibson was his failure to get Preston North End promoted to the First Division of the Football League.

Alex Gibson bought Bill Tremelling from Blackpool in 1930. At first he played at centre-forward and scored two goals on his debut. However, later in the season he was moved to centre-half and eventually became captain of the side.

Preston only finished in 7th place in the 1930-31 season and Alex Gibson lost his job and was replaced by Lincoln Hyde. In his first year in the job Preston finished in 13th place and at the end of the 1931-32 season he was sacked.

In 1931 Blackburn Rovers sold Ted Harper to Preston for £5,000. In his first season Harper scored 24 league goals in 23 games.

In 1932 Preston signed the 39 year old Robert Kelly. The England international had helped achieve success for previous clubs Burnley, Sunderland and Huddersfield Town. George Holdcroft, a goalkeeper from Everton, also joined that year. He made his debut at Southampton on 24th December 1932. Holdcroft went on to play in 172 consecutive Football League and FA Cup matches.

Preston also signed two young talented midfielders who had born in Scotland. Both men were destined to have a considerable impact on the fortunes of the club. Bill Shankly, who was only 20 years old at the time, had been playing for Carlisle United and 21 year old, Jimmy Milne, was recruited from Dundee United.

These new players joined a talented squad that included Ted Harper, Robert Batey, Frank Gallimore, Bill Tremelling, John Pears, Billy Hough, Henry Lowe, George Fitton, Frank Beresford and George Bargh.

Ted Harper had a great start to the 1932-33 season. He scored four against both Burnley and Lincoln City and hat-tricks against West Ham United and Manchester United. By the end of the season he had scored 37 league goals, beating the club record previously held by Tommy Roberts. Despite Harper's goals, Preston only finished in 9th position and once again failed to get promotion to the First Division.

The following season Ted Harper moved back to Blackburn Rovers in order to get First Division football. During his time at Preston he had scored 67 goals in 75 games. He was replaced by the English international, George Stephenson, who had considerable goalscoring success at Derby County, Aston Villa and Sheffield Wednesday. Stephenson formed a good partnership with another former English international, Robert Kelly.

John Palethorpe was recruited from Stoke City and another experienced striker, Jimmy Dougal, joined the club half-way through the 1933-34 season.

Preston at last achieved promotion to the First Division when they finished runners-up to Grimsby Town. George Stephenson had a great season scoring 16 goals in 25 games whereas John Palethorpe scored 11 in 18.

Robert Kelly, now aged 41, was considered too old for First Division football and was allowed to become player manager at Carlisle United. Stephenson, at 34, was also considered past his best and was allowed to join Charlton Athletic.

Preston signed another veteran, Ted Critchley, to replace Kelly. Critchley had been a member of Everton's 1926-27 and 1931-32 championship winning-sides. He had been the main supplier of the crosses that enabled Dixie Dean to score so many goals at Everton. However, Critchley was past his best and only played in the first 11 games of the season before losing his place in the team.

Other players brought in that year included Jimmy Maxwell (Kilmarnock), Les Vernon (Bury) and Albert Butterworth (Blackpool). In the 1934-35 season Preston finished 11th in the league. Maxwell, who played at centre-forward, was the club's leading scorer with 26 league and cup goals.

The following season Preston persuaded the Scottish international, Tom Smith, to join the club. This strong centre-half brought stability to the defence. Other signings that year included the brothers, Hugh O'Donnell and Frank O''Donnell from Celtic.

In the 1935-36 season, Preston finished 7th in the league. Jimmy Maxwell was again top scorer with 19 goals in all competitions. New signing, Hugh O'Donnell, added 15 more. Preston had a disappointing league campaign in 1936-37 only finishing in 14th place. Frank O''Donnell was top scorer with 27 goals. Eleven of these came in cup competitions. For example, he scored in every round of the FA Cup, including a hat trick in the 4th round against Exeter City and a double against West Bromwich Albion in the semi-final. O'Donnell also scored in the first-half of the cup final against Sunderland.

Preston held the lead until early in the second-half. In the 52nd minute Eddie Burbanks took a corner. Raich Carter headed the ball to Bob Gurney, who back-headed the ball into the net. Carter, was a growing influence on the game and in the 72nd minute he lobbed Sunderland into the lead. Six minutes later, Patsy Gallacher created a third goal with a skilfully judged pass to Burbanks who shot home from a narrow angle. Carter had led Sunderland to its first FA Cup final victory.

At the beginning of the next season, Preston made two important signings. In September, 1937, Preston purchased the high scoring George Mutch, from Manchester United for £5,000. The following month, Robert Beattie a skillful inside forward, arrived from Kilmarnock for a fee of £2,500. They joined fellow Scotsmen, Bill Shankly, Jimmy Dougal, Andrew Beattie, Jimmy Maxwell, Tom Smith, Hugh O'Donnell, Frank O''Donnell, Andrew McLaren, Jimmy Milne, John Cox and Jimmy McIntosh. The squad also included Bill Tremelling, Frank Gallimore, Leonard Gallimore, George Holdcroft, Henry Lowe, Les Vernon and Dickie Watmough.

George Mutch repeated the success he had at Manchester United (48 goals in 112 games). Soon after signing he scored two goals in Preston's victory over Everton. He also scored a hat trick when Preston beat West Ham United in the 3rd round of the FA Cup. Mutch also scored goals in the 4th round against Leicester City and in the semi-final when Preston beat Aston Villa 2-1. In the 1938 FA Cup Final Preston played Huddersfield Town. This was the first time that a whole match was shown live on television. Even so, far more people watched the game in the stadium as only around 10,000 people at the time owned television sets. No goals were scored during the first 90 minutes and so extra-time was played. In the last minute of extra-time, Bill Shankly put George Mutch through on goal. Alf Young, Huddersfield's centre-half, brought him down from behind and the referee had no hesitation in pointing to the penalty spot. Mutch was injured in the tackle but after receiving treatment he got up and scored via the crossbar. It was the only goal in the game.

In the 1937-38 season Preston North End challenged Arsenal for the First Division title. In the final match of the season the two teams played each other. During the game Jimmy Milne broke his collarbone in a collision with Alf Kirchen. Ten man Preston lost 3-1 and Arsenal won the championship. Top scorers were Scotsmen George Mutch (18) and Jimmy Dougal (14).

Bill Shankly had a magnificent season and on 9th April, 1938 he won his first international cap when he played for Scotland against England at Wembley. Also in the Scottish team were Preston colleagues, George Mutch, Andrew Beattie, Tom Smith and Frank O'Donnell. Scotland won 1-0 with Mutch scoring the only goal of the game. Later that season, two other Preston players, Jimmy Dougal and Robert Beattie, were called up to play for Scotland.

Preston finished in 9th place in the 1938-39 season. Jimmy Dougal was the club's leading scorer with 19 goals. Preston had a good run in the FA Cup until being knocked out by Portsmouth in the sixth round.

On Friday, 1st September, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. The football that Saturday went ahead as Neville Chamberlain did not declare war on Germany until Sunday, 3rd September. The government immediately imposed a ban on the assembly of crowds and as a result the Football League competition was brought to an end.

On 14th September, the government gave permission for football clubs to play friendly matches. In the interests of public safety, the number of spectators allowed to see these games was limited to 8,000. These arrangements were later revised, and clubs were allowed gates of 15,000 from tickets purchased on the day of the game through the turnstiles.

The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place. Preston North End became a member of the North West Regional League. In the 1939-40 season Preston finished in second place, only two points behind the winners, Bury.

After the declaration of war in September 1939, Adolf Hitler did not order the attack of France or Britain as he believed there was still a chance to negotiate an end to the conflict between the countries. This period became known as the Phoney War. As Britain had not experienced any bombing raids, the Football League decided to start a new competition entitled the Football League War Cup.

The entire competition of 137 games including replays was condensed into nine weeks. However, by the time the final took place, the "Phoney War" had come to an end. On 10th May, 1940, Adolf Hitler launched his Western Offensive and invaded France. In the days leading up to the final, the British Expeditionary Force was being evacuated from Dunkirk. In the final West Ham United beat Blackburn Rovers 1-0.

Preston North End also took part in the 1941 Football League War Cup. In the first two rounds Preston beat Bury and Bolton. In the next round Andrew McLaren scored five of the goals in Preston's 12-1 victory over Tranmere. He also scored a hat-trick in the fourth-round tie against Manchester City. Preston reached the final by beating Newcastle United 2-0.

The Preston team that faced Arsenal at Wembley on 31st May was: Jack Fairbrother, Frank Gallimore, William Scott, Bill Shankly, Tom Smith, Andrew Beattie, Tom Finney, Andrew McLaren, Jimmy Dougal, Robert Beattie and Hugh O'Donnell. Preston played Arsenal in front of a 60,000 crowd. Arsenal was awarded a penalty after only three minutes but Leslie Compton hit the foot of the post with the spot kick. Soon afterwards Andrew McLaren scored from a pass from Tom Finney. Preston dominated the rest of the match but Dennis Compton managed to get the equaliser just before the end of full-time.

Leslie Compton (Arsenal) during the 1941 Football League Cup Final. The ball

hit the post and bounced back into play.

The replay took place at Ewood Park, the ground of Blackburn Rovers. The first goal was as a result of a move that included Tom Finney and Jimmy Dougal before Robert Beattie put the ball in the net. Frank Gallimore put through his own goal but from the next attack, Beattie scored again. It was the final goal of the game and Preston ended up the winners of the cup.

In the 1940-1941 season Preston North End needed to win their last game against Liverpool to win the North Regional League title. The nineteen year old Andrew McLaren scored all six goals in the 6-1 victory. There is no doubt that during this period Preston was the best football club in England.

During the 1940-41 season Tom Finney played in 41 games. Others involved in this great season included Jimmy Dougal (40), Andrew McLaren (39), Frank Gallimore (38), Tom Smith (38), William Scott (38), Jack Fairbrother (27), Bill Shankly (25), William Jessop (25), George Mutch (17), Robert Beattie (15), George Holdcroft (14) and Hugh O'Donnell (10). Top scorers for that season were: Dougal (32) and McLaren (31).

It has been argued by Jack Rollin (Soccer at War: 1939-45) that: "The first club to benefit from a youth policy to any marked degree was Preston North End, who owed success in 1940-41 to their exceptional pre-war structure. By 1938 the club was already running two teams in local junior circles when the chairman James Taylor decided upon a scheme to fill the gap between school leavers and junior clubs by forming a Juvenile Division of the Preston and District League open to 14-16-year-olds."

Rollin points out that by 1940 over 100 youngsters were being trained in groups of eight of the club's senior players voluntarily assisting in evening coaching. Robert Beattie was one of those involved in this coaching. This system produced Tom Finney, Andrew McLaren, William Scott and William Jessop.

This great Preston team was broken up by the Second World War. In 1942 Tom Finney, their star player, was called up to the Royal Armoured Corps and later fought under General Bernard Montgomery in the Eighth Army in North Africa.

on the outbreak of the war.

The British Army invited some of the best footballers to became Physical Training instructors at Aldershot. Others served abroad. This included Andrew Beattie and Robert Langton who was sent to India. Seventy professional football players were killed during the Second World War. This included Percival Thomas Taylor, who made five appearances in wartime football for Preston North End. Taylor scored a hat trick while playing as a guest for Middlesbrough against Bradford City on 4th April 1942. He was killed in a motor cycle accident six days later.

Preston kit in 1935.

aid at the local Air Raid Precautions centre in November, 1939.

According to the Football Association publication, Victory Was The Goal (1945), between 3 September 1939 and the end of the war, 55 went from Preston North End. While some footballers joined the armed forces, others found occupation in the support services. For example, Preston player's Jack Fairbrother and Willie Hamilton joined the police force in Blackburn.

Preston North End's Deepdale ground was used to hold captured prisoners during the Second World War. The military gave the club £250 a year in compensation for having to play on other grounds.

Primary Sources

(1) Bob Holmes, Lancashire Daily Post (July, 1898)

I am not quite sure that we shall succeed in attaining all the objects with which we set out; it is not a certainty that we shall carry any... The break-up of the Everton team as we knew it last season may have a good deal in influencing the future of the Union. With John Cameron, Jack Bell, Robertson, Holt, Stewart, Storrier, Meecham of Everton as well as Hartley and Bradshaw of Liverpool gone, our centre has lost strength. Liverpool was our headquarters, you know, and our registered offices were there. But the secretary, John Cameron, has gone to London and Bell the chairman will not, as far as I know, play for anybody."

(2) Barbara Jacobs, The Dick, Kerr's Ladies (2004)

The official website of the Football League claims that the first football manager to bring in night matches, under floodlight, was Herbert Chapman of Huddersfield, in the late 1920s. In fact, it had been tried before, in Birmingham and Lincoln but the lighting wasn't powerful enough to make the game visible, and maybe Herbert was the first manager to introduce floodlit football on a regular basis, but Alfred Frankland and a squad of engineers from Dick, Kerr's English Electric factory actually managed to make floodlit football a possibility. The unique relationship which existed between the company and the Army barracks at Fulwood was the key, and Dick, Kerr's engineers came up with the solution. Two Army surplus searchlights should do the trick. So, these were duly ordered from the War Office - can you believe it? - and were delivered to the Preston railway station the day before. To augment those, 40 carbide flares were put into position around the edge of the pitch, also supplied by Frankland's contacts in Fulwood barracks. Flares were placed at the turnstiles and to celebrate this extraordinary occasion not one, but three brass bands were requisitioned to lead torch-lit processions of spectators to the ground. And the Pathe News team was alerted to this experimental exercise in pre Christmas jollity and turned out to make of it what they could.As a spectacle, it was far more exciting than any of the previous Christmas processions and celebrations for which Lancashire is famous. Men in flat caps, women in large hats, small children skipping along, processed to the Deepdale ground, so that later they could tell their own children, 'I was there when we played football by searchlight!'The Ladies too, were excited, all of a fluster and a giggle. Back to their old selves. Lily did her Blind-Man's Buff impression, mimicking searching for little Jennie Harris through the dark by touch only. The opposing team was to be `The Rest of Lancashire' and included two St Helens girls who had been tempted by the prospect of hunt the football. It could all have gone horribly wrong, but I doubt it, because even horribly wrong would have been funny.And it was. Hilarious mayhem ensued. Picture it - on the touchline was the famous Bob Holmes whom I've mentioned before, throwing whitewashed balls on to the pitch, in the stands were scores of big lusty Lancashire lasses with their husbands, doubled up with laughter, and on the pitch were Lily and Alice and the others, wondering what damage they could do in the darkness. Except that it wasn't dark. It was glaringly bright, until one of the searchlights got an airlock and went out barely into the first half. Then one of the searchlight operators from the factory became very excited by a defensive tackle, and turned up his searchlight so strongly that both attacker and defender were temporarily blinded and keeled over. Then Jennie Harris, as willing as ever, kept making searching runs up the left, only to be halted by the sudden glare of flash-bulbs and skied the ball from 5 yards out.

(3) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

Although football dominated my early life - that should probably read my entire life come to think of it - opportunities for watching the game were restricted. Apart from anything else, I was always too busy playing. But as a proud Prestonian, I was acutely aware of Preston North End Football Club and, in common with the other lads who kicked a rubber ball around the back fields of Holme Slack, my dream was to be the next Alex James.

James was the top star of the day, a genius. There wasn't much about him physically, but he had sublime skills and the knack of letting the ball do the work. He wore the baggiest of baggy shorts and his heavily gelled hair was parted down the centre. On the odd occasion when I was able to watch a game at Deepdale, sometimes sneaking under the turnstiles when the chap on duty was distracted, I was in awe of James. Preston were in the Second Division and the general standard of football was not the best, but here was a magic and a mystery about James that mesmerised me.

The man behind Preston's capture of James was chairman Jim Taylor, who later signed me and went on to play a major part in my early career.

The son of a railwayman and a native of North Lanarkshire, Alex James was a steelworker when his football talents were first spotted by Raith Rovers in the year of my birth. He earned good money north of the border - £6 in the winter and £4 in the summer - and his form brought the scouts flocking in. Preston were always well served with 'spies' in Scotland and while his short stature and dubious temperament caused a few potential buyers to dither, Jim Taylor was more bullish. In the June of 1925, the chairman went in with a £2,500 bid - an offer later raised to £3,500 to ward off a late inquiry from Leicester City. Taylor had his man and the signing of James proved a masterstroke. The supporters loved him, a fact reflected in the attendances, which rose by around £300 per game. He was box office, the draw card, a player who grabbed your attention and refused to let go.

James was a character off the field, too. He liked clubs - of the night-time variety - owned a car and, by all accounts, enjoyed playing practical jokes on his colleagues. But he was also a perfectionist, a footballer acutely aware of both his ability and his responsibility. The experts scratched their heads about why his talent was being allowed to languish outside the top flight and it wasn't long before Arsenal came in to present him with a bigger stage. He was my first football hero and my role model and when he was transferred to the Gunners I thought I would never get over it.

The kickabouts we had in the fields and on the streets were daily events, sometimes involving dozens and dozens of kids. There were so many bodies around you had to be flippin' good to get a kick. Once you got hold of the ball, you didn't let it go too easily. That's where I first learned about close control and dribbling.

It was a world of make-believe - were children more imaginative in those days? - and although we only had tin cans and school caps for goalposts, it mattered not a jot. In my mind, this basic field was Deepdale and I was the inside-left, Alex James. I tried to look like him, run like him, juggle the ball and body swerve like him. By being James, I became more confident in my own game. He never knew it, but Alex James played a major part in my development.

(4) Richard Whitehead, The Times (23rd October, 2004)

James also arrived in North London in headline-making circumstances, but only after a prolonged Nicolas Anelka-like sulk had ensured his departure from Preston North End. James was keen to earn more than the £8-a-week maximum wage, but the only way for Arsenal to circumvent the Football League’s strict regulations was for their signing to take up additional employment as a “sports demonstrator” at Selfridge’s on the impressive salary of £250.

He was not an instant success — one sarcastic fan sent him a pair of battered child’s football boots with an accompanying note suggesting “it doesn’t matter much what you wear anyhow” — but James quickly became the brains behind a team that dominated domestic football in a fashion that had not previously been seen.

Lying deeper than conventional inside forwards, he would spring Arsenal’s rapid breakaways from defence — a tactic that earned them the tag “lucky Arsenal” from disgruntled opposing fans who had frequently seen their team dominate territorially for no tangible reward.

That tactic demonstrated the quality the little man with the commodious shorts shared most with his modern-day counterpart — the ability to hit passes so stunningly beautiful that they could adorn the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

(5) Stephen F. Kelly, Bill Shankly (1997)

In 1933, Preston North End were a club with a rich history but a gloomy-looking future... When Bill Shankly landed on their doorstep, they were little more than a moderate Second Division side. They had been relegated in 1925 along with Nottingham Forest and had struggled ever since to escape the anonymity of Second Division soccer. In the season before Shankly arrived, they had finished ninth in the table, fourteen points adrift of champions Stoke City.

Like so many other industrial cities, Preston suffered appallingly during the thirties. The Depression hit Lancashire hard. Across the country, the number of unemployed rose to 2.9 million, a staggering 20% of the working population and, if those who were unregistered were included, the total was nearer three-and-a-half million. Everywhere, the unemployed protested.

In Lancashire, they marched to Preston and in Scotland they descended on Glasgow, while those from Jarrow in the North-east marched bravely to London, pricking the conscience of the nation. The politicians called the unemployed regions Distressed Areas. It somehow sounded better. Unemployment benefit was basic if not downright miserable. The Means Test, with its crippling rules, ensured that money was only forthcoming if certain stringent criteria were met. And, when money was paid out, it was done so begrudgingly and in small amounts. Few claimants met the criteria; most survived thanks only to family and friends.

In some areas of Lancashire, unemployment topped the 25% mark. Preston was a cotton-spinning town and like all the cotton towns of Lancashire had been severely shaken by the Depression. Almost half a million cotton workers were on the dole. Exports to India had crashed. Looms lay idle; mills were closing. Unemployment in Preston, even though it hit an all-time high, may not have been as bad as some parts of Lancashire, like Mersyside and Blackburn, but there were still more than 15% on the dole...

Shankly was as aware as anyone of the problems of unemployment: he'd seen it all before. In Ayrshire, his family and friends had suffered as the mines closed and it was little better in Carlisle. He'd spent a couple of months on the dole himself and was well aware of the humiliations that unemployment brought. But in case he had forgotten, he was to be rudely awoken by what he saw in Preston.

Shankly was lucky. At the end of his first season, his wages had risen to £8 with £6 in summer, a small fortune in a place like Preston. It allowed for the luxury of going out occasionally though, as ever, much of his money was sent home to his family in Ayrshire. But it would get better. Shankly arrived at the peak of unemployment and, as the thirties unwound, jobs were beginning to return and with them wealth creation. Even the fortunes of Preston North End began to look up...

It was a learning process and Shankly was developing as rapidly as anyone. By December, he had made the first team. He made his debut against newly promoted Hull City on Saturday 9 December. Ironically, Shankly had played against Hull just a few months earlier when he was with Carlisle and had been on the wrong end of a 6-1 drubbing. This time, the boot was on the other foot. Preston won 5-0. Preston were three goals up within half an hour with Shankly having a hand in the second goal. His arrival did not go unnoticed in the press. 'Shankly passed the ball cleverly,' reported the Sporting Chronicle without going into further detail. It was probably the first time his name had appeared in a national paper.

By the end of the season, Preston had clinched promotion as runners-up to champions Grimsby. It was to be the start of a famous period in Preston's history. They had begun the season confidently and after a couple of games were topping the table. By October however, they had slipped and by early December they were down to seventh place. But then the inclusion of Shankly seemed to revive them. Their win over Hull hoisted them into sixth spot, some way behind Grimsby who were runaway leaders almost the entire season.

Preston were not always obvious promotion candidates. One week, they would shoot up the table and, overtake their promotion rivals, only to lose their next game and slither back the following one. Grimsby had clinched promotion by early April, but the second promotion place remained in doubt until the final day of the season.

It was neck and neck between Bolton Wanderers and Preston, two of Lancashire's most famous clubs. Both teams had 50 points from 41 games: Bolton looked to have the easier final fixture with a visit to Lincoln, while Preston were at Southampton. But much to everyone's surprise, Bolton could manage only a draw while Preston won 1-0 and were into the First Division. After making his debut in December, Shankly had gone on to play all season. Once he was in the side, he was there to stay and undoubtedly became an important influence on Preston's promotion challenge.

(6) Jack Rollin, Soccer at War: 1939-45 (1985)

The first club to benefit from a youth policy to any marked degree was Preston North End, who owed success in 1940-41 to their exceptional pre-war structure. By 1938 the club was already running two teams in local junior circles when the chairman James Taylor decided upon a scheme to fill the gap between school leavers and junior clubs by forming a Juvenile Division of the Preston and District League open to 14-16-year-olds.

(7) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003)

I vividly recall Neville Chamberlain's depressing broadcast to the nation on that Sunday morning, 3 September 1939, two days after German forces had invaded Poland. After attending morning service at St Jude's, I called in on a mate of mine, Tommy Johnson, a fellow plumber, and he was glued to the wireless as the news we all dreaded came through.

League football was suspended, players were told that they would be paid up to the end of the week only, and supporters were informed that there would be no refund on season tickets. Andy Beattie, another of North End's 'Great Scots' and a man for whom I held the utmost respect, was due a richly deserved benefit match. The war ensured that didn't materialise. Contracts were effectively cancelled although clubs retained players' registrations.

Preston made strenuous efforts to get players fixed up with jobs - Bill Shankly found employment shovelling sand, George Mutch building aeroplanes and Jack Fairbrother joined up as a policeman. Troops were stationed at Deepdale, and police and military use of the ground continued through until 1946.

Wartime football was no substitute for the real thing but it did serve a purpose. There were restrictions galore and most clubs found their squads decimated through call-ups into the armed services, but the public passion for football won through. Sometimes matches were in doubt right up to kick-off as clubs tried desperately to recruit some guest players, but when the action rolled it was good. Football provided the country with some much-needed escapism and, speaking as a player, it was thoroughly enjoyable - despite the bombs. After we had lost 2-0 at Anfield, our coach-ride home was caught up in an air-raid on Merseyside and that was a frightening experience by any standards.

The 1940-41 season was a shortened affair but Preston United did well. We finished as Northern Section champions, which was some achievement considering the fact that we had struggled at the wrong end of the First Division up to war being declared.

(8) Dean Hayes, Who's Who of Preston North End (2006)

One thing on which all who played with or against Tom Finney agree is that, in addition to all his skill, he never lacked courage. In his time he took a large amount of punishment. this is reflected in the fact that he missed 115 matches - most of them in ones, twos and threes - through injury of one kind of another.