Black Footballers

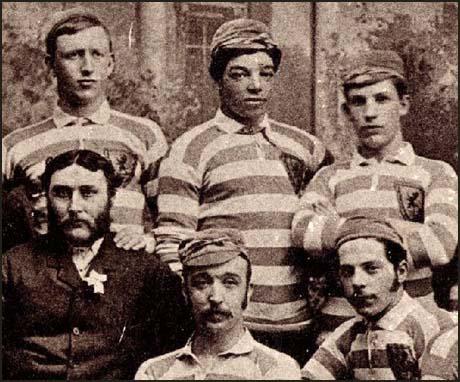

The first black player to play top level football in Britain was Andrew Watson. The son of a Scottish sugar planter Peter Miller and a local girl Rose Watson, he was born in Georgetown, British Guiana in 1857. Watson was sent to England to be educated at Halifax Grammar School and Rugby College before enrolling at Glasgow University in 1875 to study Philosophy, Mathematics and Civil Engineering.

Andrew Watson was a talented player and joined Queen's Park, at the time, the best club in Scotland. He also became club secretary and led his team to several Scottish Cup wins. On 12th March 1881 Watson won his first international cap when he played as right-back for Scotland against England. He was captain and led his country to a 6-1 victory. Two days later he played in the team that beat Wales 5-1. The following year he won his third cap when Scotland beat England 5-1.

Watson sacrificed his international career when he moved to England in 1882. The Scottish Football Association refused to select men who played football outside Scotland. Watson joined London Swifts and in 1882 he became the first black man to play in the FA Cup. In 1884 he joined the elite amateur club, Corinthians.

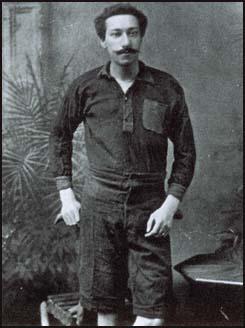

Arthur Wharton was born in Accra, Ghana on 28th October, 1865. Of mixed race, Wharton moved to England in 1882 to train as a Methodist missionary. Wharton was an outstanding athlete and eventually decided to concentrate on being a sportsman. In July, 1886, he set a new world record when he ran the 100 yards at Stamford Bridge in 10 seconds. This performance brought him to the attention of Major William Sudell, the manager of Preston North End and he joined the club later that year. Despite his tremendous speed he played in goal. In 1887 he played against West Bromwich Albion in the FA Cup semi-final but lost 3-1.

In 1889 Wharton signed for Rotherham United. After five years he moved on to Sheffield United. When living in Sheffield he was employed to run the Sportsman Cottage public house in the city. Wharton had difficulty holding his place in the team and was eventually replaced by Bill Foulke.

According to Phil Vasili, the author of Colouring Over the White Line: The History of Black Footballers in Britain (2000), the next black player to play professional football in England was Fred Corbett who played centre-forward for West Ham United between 1900-02 before moving on to Bristol Rovers, Bristol City and Brentford.

Hassan Hegazi, who had been born in Cairo, Egypt, played for Fulham. A talented footballer he played in the club's 3-1 win over Stockport County. He scored one of the goals and the Fulham Observer commented that "with persistence something might be made of him... Hegazi has the makings of a League player." Hegazi also played for Millwall before completing his studies at Cambridge University.

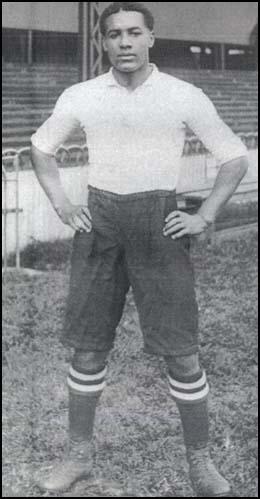

In 1908 Tottenham Hotspur signed Walter Tull, a 20 year old apprentice printer. Tull scored 2 goals in 10 games in the 1909-1910 season before being transferred for a large fee to Northampton Town.

Walter Tull played 110 times for Northampton Town's first-team. Playing at wing-half, Walter became the club's most popular player. Other clubs wanted to sign Walter and in 1914 Glasgow Rangers began negotiations with Northampton Town. However, before he could play for them war was declared.

On the outbreak of the First World War Tull immediately abandoned his career and offered his services to the British Army. Tull, like many professional players, joined the 1st Football Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. The Army soon recognized Tull's leadership qualities and he was quickly promoted to the rank of sergeant. In July 1916, Tull took part in the major Somme offensive. Tull survived this experience but in December 1916 he developed trench fever and was sent home to England to recover.

Walter Tull had impressed his senior officers and recommended that he should be considered for further promotion. When he recovered from his illness, instead of being sent back to France, he went to the officer training school at Gailes in Scotland.

Lieutenant Walter Tull was sent to the Italian front. This was an historic occasion because Tull was the first ever black officer in the British Army. He led his men at the Battle of Piave and was mentioned in dispatches for his "gallantry and coolness" under fire.

Walter Tull stayed in Italy until 1918 when he was transferred to France to take part in the attempt to break through the German lines on the Western Front. On 25th March, 1918, 2nd Lieutenant Tull was ordered to lead his men on an attack on the German trenches at Favreuil. Soon after entering No Mans Land Tull was hit by a German bullet. Tull was such a popular officer that several of his men made valiant efforts under heavy fire from German machine-guns to bring him back to the British trenches. These efforts were in vain as Tull had died soon after being hit. Tull's body was never found.

After the war, London born Jack Leslie, became a prolific scorer with Plymouth Argyle. His manager, Bob Jack, told him he had been selected to play for England. However, the invitation to play for his country was withdrawn. Leslie told the journalist, Brian Woolnough: "They must have forgot I was a coloured boy."

Hong Ying Soo, who had a Chinese father, was another non-white player who was considered by many to be good enough to play for England. His career was interrupted by the Second World War but he did play in nine unofficial English internationals during the conflict. Roy Brown was another non-white player who was believed to be good enough to play for England. Brown had a Nigerian father, Eugene Brown, and a English mother. Like Hong Ying Soo, Brown had a successful career with Stoke City.

Two other black footballers made an impact between the two wars. Salim Bachi Khan, an Indian international, played barefoot for Glasgow Rangers in the 1936-37 season. Alfred Charles, who was born in Trinidad, was a centre forward who played for Southampton in 1936.

Primary Sources

(1) Phil Vasill, Colouring Over the White Line: The History of Black Footballers in Britain (2000)

As a goalkeeper, one of his trademarks was his 'prodigious punch'. There were always two targets (yes, even when he was sober): the ball and the opponent's head, and he'd always connect with one. A number of match reports mention the run-ins he had with forwards. Goalkeepers could handle the ball anywhere in their own half and could be shoulder-charged with or without the ball. This physicality appealed to Arthur Wharton.

(2) Athletic Journal (29th October, 1887)

Good judges say that if Wharton keeps goal for Preston North End in their English Cup tie the odds will be considerably lengthened against them. I am of the same opinion ... Is the darkie's pate too thick for it to dawn upon him that between the posts is no place for a skylark? By some it's called coolness - bosh!'

(3) T. H. Smith, letter to the Sheffield Telegraph and Independent (12th January, 1942)

In a match between Rotherham and Sheffield Wednesday at Olive Grove I saw Wharton jump, take hold of the cross bar, catch the ball between his legs, and cause three onrushing forwards - Billy Ingham, Clinks Mumford and Micky Bennett - to fall into the net. I have never seen a similar save since and I have been watching football for over fifty years.

(4) Jeffrey Green, Black Edwardians (1998)

Walter Tull's first match for Spurs was at their first division debut in 1909. The London team had crowds that numbered thirty thousand, and they thrilled to Tull's skills. He was an inside forward, with the role of supplying the winger with good passes. The Daily Chronicle observed that Tull was a class above many of his team mates. It was felt that had Spurs obtained a decent winger then the combination would have been the best in England. Newspaper reports of Spurs matches refer to Tull as "West Indian" and "darkie".

(5) The Daily Chronicle (9th October, 1909)

Tull's ... display on Saturday must have astounded everyone who saw it. Such perfect coolness, such judicious waiting for a fraction of a second in order to get a pass in not before a defender has worked to a false position, and such accuracy of strength in passing I have not seen for a long time. During the first half, Tull just compelled Curtis to play a good game, for the outside-right was plied with a series of passes that made it almost impossible for him to do anything other than well.

Tull has been charged with being slow, but there never was a footballer yet who was really great and always appeared to be in a hurry. Tull did not get the ball and rush on into trouble. He let his opponents do the rushing, and defeated them by side touches and side-steps worthy of a professional boxer. Tull is very good indeed.

(6) Northampton Echo (9th October, 1909)

A section of the spectators made a cowardly attack upon him (Walter Tull) in language lower than Billingsgate...Let me tell these Bristol hooligans (there were but few of them in a crowd of nearly twenty thousand) that Tull is so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football whether they be amateur or professional. In point of ability, if not in actual achievement, Tull was the best forward on the field.

(7) The Guardian (25th March, 1998)

Playing at inside left, Tull's future looked bright. Then, in a game at Bristol City in 1909, he was racially abused by fans in what the Football Star called "language lower than Billingsgate". The incident was deeply traumatic for Tull and the club. The following season, he played only three first-team games; the season after, he was sold for "a heavy transfer fee" to Northampton Town. There, Tull flourished again, playing 110 first-team games for the club, mostly at wing-half. He was probably their biggest star. In 1914, he was on the point of signing for Glasgow Rangers. Then came war. It was perhaps inevitable, given the spirit of muscular Christianity in which he was raised, that Tull should make a swift transition from sport to war. What was less inevitable was that he should conduct himself with even more distinction on the battlefield than on the playing field. Yet he did. He enlisted in the 17th (1st. Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, alongside many other professional footballers. By 1916, he had been made a sergeant. Among other actions, he was involved in the murderous first battle of the Somme. We can only guess the horrors he endured, but they did not break him.

(8) In his book Goodbye to All That, Captain Robert Graves wrote about what happened when a popular officer was wounded in No Mans Land.

Sampson lay groaning about twenty yards beyond the front trench. Several attempts were made to rescue him. He was badly hit. Three men got killed in these attempts: two officers and two men, wounded. In the end his own orderly managed to crawl out to him. Sampson waved him back, saying he was riddled through and not worth rescuing; he sent his apologies to the company for making such a noise. At dusk we all went out to get the wounded, leaving only sentries in the line. The first dead body I came across was Sampson. He had been hit in seventeen places. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death.

(9) Walter Tull's commanding officer in the 23rd Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, sent a letter to Edward Tull after the death of his brother (March, 1918)

He was popular throughout the battalion. He was brave and conscientious. The battalion and company had lost a faithful officer, and personally I have lost a friend.

(10) Phil Vasill, Colouring Over the White Line: The History of Black Footballers in Britain (2000)

The best team and most prestigious club he (Arthur Wharton) kept for, Preston North End, had been renowned for ignoring the ban on paying players before professionalism was legalised in 1885. Yet when Arthur signed for the Deepdale club in 1886, it was as an amateur. Major Wiliam Sudell, the Preston manager who had been instrumental in forcing the FA to accept the right of footballers to be paid, went after Arthur specifically because he was the best amateur goalie around. Though the Major had won his battle to be allowed to pay players, the new rules governing their eligibility for the FA Cup had the effect of excluding many professionals from taking part in this, the only national competition. So the Preston North End Football Club and cotton-mill manager went after some top-drawer amateurs, one of whom was Arthur. However, it's a racing certainty that the Cleveland College student would have enjoyed a life of Riley on the expenses paid by Sudell. In fact the Major was jailed in 1895 for playing the role of Big Time Charlie by spending over £5,000 (which belonged to the Preston mill he managed) on expense and hospitality payments to Preston players.

(11) Phil Vasill, Colouring Over the White Line: The History of Black Footballers in Britain (2000)

As a goalkeeper, one of his trademarks was his 'prodigious punch'. There were always two targets (yes, even when he was sober): the ball and the opponent's head, and he'd always connect with one. A number of match reports mention the run-ins he had with forwards. Goalkeepers could handle the ball anywhere in their own half and could be shoulder-charged with or without the ball. This physicality appealed to Arthur Wharton.