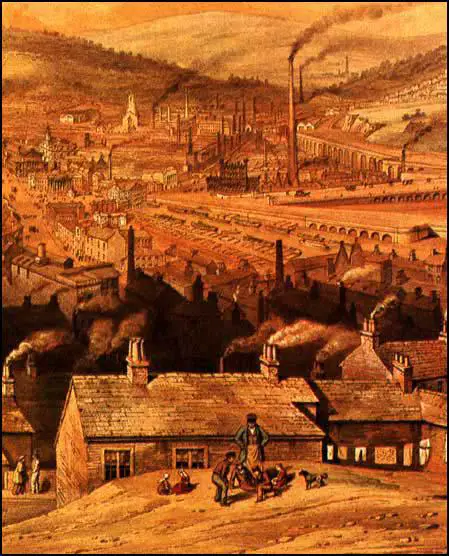

Sheffield

Situated on the River Don, Sheffield is surrounded by seven hills that contain iron ore and by the 16th century had obtained a reputation for its production of knives, scissors, scythes and shears. These goods were mainly made in houses and small workshops. By the 18th century Sheffield also became an important coal mining area. In 1796 the population of the town was 9,095.

In 1742 Thomas Boulsover, a Sheffield cutler, began to fuse a thin layer of silver to copper to produce what became known as Sheffield Plate. Other craftsmen in Sheffield began to use this method to produce tableware that looked like silver, at a fraction of its cost.

The 1840s saw another important development that was to contribute to Sheffield's prosperity. Benjamin Huntsman, working at a foundry at Handsworth, 4 miles east of Sheffield, discovered how to make good quality hard steel with less expenditure of labour and fuel. This stimulated the trade and by 1787 there were eleven steel-makers using the Huntsman method.

During the second half of the 18th century industrial development and a growth in population increased the demand for houses. Terraces of small houses were built on the colder, northern slopes, whereas the successful business community built their larger houses on the higher, south-facing slopes of the town.

The 1821 the population of Sheffield had reached 31,314. Over the next forty years the population grew rapidly and by 1861 the number of inhabitants had reached 185,000.

Primary Sources

(1) Daniel Defoe, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724)

Leaving Doncaster, we turned out of the road a little way to the left, where we had a fair view of that ancient cutlering town, called Sheffield. The town is very populous and large, the streets narrow, and the houses dark and black, occasioned by the continued smoke of the forges, which are always at work. Here they make all sorts of cutlery ware, but especially that of edged-tools, knives, razors, axes and nails. The manufacture of hardware has increased so much that they told us that 30,000 men are employed.

(2) Angus Reach, The Morning Chronicle (1849)

In Sheffield there are many old, crowded, and filthy localities, and a very considerable proportion of the operatives' dwellings are constructed back to back. Generally speaking, the cottage houses contain a small cellar, a living room about twelve feet square, a chamber of the same size above, and, in perhaps one-half of the entire number, an attic about seven feet high over the chamber. Cases are rare in which more than one artisan's family inhabit the same house, and cellar dwellings are totally unknown.

Diseases of the lungs and air passages are, it is well-known, the most fatal and characteristic complaints of Sheffield. Amongst the diseases of the air passages are reckoned cases of bronchitis, pleuritis, asthma, catarrh, and phthisis.

Several of the grinding processes, by the quantities of excessively fine steel-dust flung into the atmosphere, are frequently and rapidly fatal to those engaged in them; while the bending and stooping postures necessary in all grinding, wet as well as dry, have necessarily their more gradually prejudicial effect. The average age of death of the gentry and professional person in Sheffield is 45.90, that of saw-makers is only 13.94, and that of various grinders, 18.15.

(3) George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937)

Sheffield, I suppose, could justly claim to be called the ugliest town in the Old World: its inhabitants, who want it to be pre-eminent in everything, very likely to make that claim for it. It has a population of half a million and it contains fewer decent buildings than the average East Anglican village of five hundred. And the stench! If at rare moments you stop smelling sulphur it is because you have begun smelling gas. Even the shallow river that runs through the town is usually bright yellow with some chemical or other.

Once I halted in the street and counted the factory chimneys I could see; there were thirty-three of them, but there would have been far more in the air had not been obscured by smoke. One scene especially lingers in my mind. A frightful patch of waste ground trampled bare of grass and littered with newspapers and old saucepans. To the right an isolated row of gaunt four-roomed houses, dark red, blackened by smoke. To the left an interminable visa of factory chimneys, chimney beyond chimney, fading away into a dim blackish haze. Behind me a railway embankment made of slag from furnaces. In front, across the patch of waste ground, a cubical building of red and yellow brick, with the sign 'Thomas Grocock, Haulage Contractor'.