On this day on 28th March

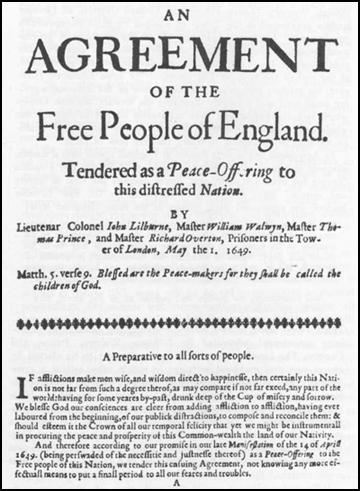

On this day in 1649, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton and William Walwyn, were also taken into custody and all were brought before the Council of State in the afternoon. John Lilburne later claimed that while he was being held prisoner in an adjacent room, he heard Cromwell thumping his fist upon the Council table and shouting that the only "way to deal with these men is to break them in pieces … if you do not break them, they will break you!"

Price's biographer points out: "During his interrogation by the council of state, he followed his fellow Levellers in refusing to acknowledge the authority of his accusers, arguing that to do so would be a betrayal of his own and the people's liberties". As a result, Prince, Lilburne, Overton and Walwyn were committed to the Tower of London on suspicion of high treason. Nevertheless, Prince and the other Levellers managed to publish pamphlets. This included Prince's account of his arrest and examination.

In March, 1649, Prince joined forces with Lilburne and Overton to publish, England's New Chains Discovered. They attacked the government of Oliver Cromwell pointed out that: "They may talk of freedom, but what freedom indeed is there so long as they stop the Press, which is indeed and hath been so accounted in all free Nations, the most essential part thereof.. What freedom is there left, when honest and worthy Soldiers are sentenced and enforced to ride the horse with their faces reverst, and their swords broken over their heads for but petitioning and presenting a letter in justification of their liberty therein?"

On this day in 1667 John Evelyn wrote in his diary: "The Royal Society experimented with the transfusion of blood. They took blood successfully out of a sheep and put it into a dog. The sheep died but the dog is well."

On this day in 1760 Thomas Clarkson, the eldest of three children, was born in Wisbech. His father, John Clarkson (1710–1766), was the headmaster of Wisbech Grammar School. His younger brother, John Clarkson, was born on 4th April 1764.

Clarkson later wrote about his father: "The duties of the grammar school engaged nearly the whole of the day and left little more than the hours of evening for these visits of mercy and he often did not return into the town till after midnight, but he allowed neither darkness, nor the coldness of the night nor the tempestuousness of the bitterest winter weather to frustrate his design... It was on one of these visits to the sick poor of his parish, that he caught a fever which deprived him of his life. The news of his death caused an universal burst of sorrow as soon as it was known in those parts."

After the death of his father, the family continued to live in the town. In 1775 Clarkson was sent to St Paul's School. The historian, Ellen Gibson Wilson, has pointed out: "The pupils paid fees and supplied their own books. Carrying their wax candles they swarmed into the high hall each day at 7 a.m. and took their seats on the benches which rose in three tiers along the walls. It was always freezing cold; no fires were allowed at any time.

In 1779 Clarkson won a place at St. John's College, Cambridge. His biographer, Hugh Brogan, has argued: "He was a devout, assiduous soul, taking after his father, a notably conscientious parson. He seems to have had no sense of humour at all, though he liked others to be merry. Physically, he was tall and heavy, with a strong constitution. His brother John, by contrast, was small and lively, but was as strongly religious, and shared to the full his brother's strong human sympathy: he detested the navy's use of flogging as a punishment. Thomas Clarkson graduated BA in 1783 with a solid rather than a distinguished degree in mathematics, but remained at Cambridge to prepare himself to be a clergyman. He was decidedly ambitious; after winning a university Latin essay prize in 1784 he resolved to win it again the following year."

In 1785 Cambridge University held an essay competition with the title: "Is it rights to make men slaves against their will?" Clarkson had not considered the matter before but after carrying out considerable research on the subject submitted his essay. He found a book written by Anthony Benezet, entitled Some Historical Account of Guinea: An Inquiry Into the Rise and Progress of the Slave Trade, published by a recently formed Society of Friends committee. Clarkson later wrote: "In this precious book I found almost all I wanted." Clarkson won first prize and was asked to read his essay to the University Senate.

On his way home to London he had a spiritual experience. He later described how he had "a direct revelation from God ordering me to devote my life to abolishing the trade." Clarkson was worried that as a young man if he had the necessary skills to "qualify him to undertake a task of such magnitude and importance". However, each time he doubted, the result was the ame: "I walked frequently into the woods, that I might think on the subject in solitude, and find relief to my mind there. But the question still recurred... surely some person should interfere."

Clarkson read everything he could on the African slave trade. He obtained access to some "manuscript papers" of a friend who had been involved in the trade. He also interviewed some officers who had served in the West Indies. He realised that slavery was not "merely an abstract problem" as it existed in "British colonies which were governed by the laws of England, and that its existence was not only condoned by the British public but also actively encouraged by them."

Clarkson made contact with William Dillwyn, a former assistant to Anthony Benezet, but now a merchant in Britain. At his home in Walthamstow he tutored Clarkson in the anti-slavery movements on both sides of the Atlantic. Dillwyn told Clarkson about the work of James Ramsay and Granville Sharp and the attempts by the Society of Friends to bring an end to the trade.

Clarkson's close friend, Henry Crabb Robinson, commented that Clarkson became very close to the Quakers: "The gravity, great earnestness, and quakerish simplicity of his appearance.... made his presence a sort of phenomenon among great men, and men of the world. He was at home only among the Quakers." Clarkson once said of the Quakers that he shared "nine parts in ten of their way of thinking."

In June 1786 Clarkson published Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African. The book traced the history of slavery to its decline in Europe and arrival in Africa, made a powerful indictment of the slave system as it operated in the West Indian colonies and attacked the slave trade supporting it. William Smith argued that the book was a turning-point for the slave trade abolition movement and made the case "unanswerably, and I should have thought, irresistibly".

Jane Austin read the book and told her sister that its emotional impact was sp strong that she fell in love with Clarkson. Ralph Waldo Emerson argued the book was a turning point in history: "An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man... the Reformation, of Martin Luther; Quakerism, of George Fox, Methodism, of John Wesley; Abolition of Thomas Clarkson... All history resollves itself very easily into the biography of a few stout and earnest persons."

In 1787 Clarkson, William Dillwyn and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as William Allen, John Wesley, Thomas Walker, John Cartwright, James Ramsay, Charles Middleton and William Smith gave their support to the campaign. Clarkson was appointed secretary, Sharp as chairman and Hoare as treasurer. At their second meeting Hoare reported subscriptions of £136.

The highly successful businessman, Josiah Wedgwood joined the organising committee. He urged his friends to join the organisation. Wedgwood wrote to James Watt asking for his support: "I take it for granted that you and I are on the same side of the question respecting the slave trade. I have joined my brethren here in a petition from the pottery for abolition of it, as I do not like a half-measure in this black business."

As Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has pointed out: "Wedgwood asked one of his craftsmen to design a seal for stamping the wax used to close envelopes. It showed a kneeling African in chains, lifting his hands beseechingly." It included the words: "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" Hochschild goes onto argue that "reproduced everywhere from books and leaflets to snuffboxes and cufflinks, the image was an instant hit... Wedgwood's kneeling African, the equivalent of the label buttons we wear for electoral campaigns, was probably the first widespread use of a logo designed for a political cause."

Thomas Clarkson explained: "Some had them inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff boxes. Of the ladies, several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and this fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom."

Hundreds of these images were produced. Benjamin Franklin suggested that the image was "equal to that of the best written pamphlet".Men displayed them as shirt pins and coat buttons. Whereas women used the image in bracelets, brooches and ornamental hairpins. In this way, women could show their anti-slavery opinions at a time when they were denied the vote. Later, a group of women designed their own medal, "Am I Not a Slave And A Sister?"

In 1787 Thomas Clarkson met Alexander Falconbridge, a former surgeon on board a slave ship. Clarkson described Falconbridge as an "athletic and resolute-looking man". Falconbridge was willing to testify publicly about the way slaves were treated. Clarkson later recalled: "Never were words more welcome to my ears. The joy I felt rendered me quite useless... for the remainder of the day." Falconbridge accompanied Clarkson to Liverpool where he acted as his bodyguard. Falconbridge later recalled: "His zeal and activity are wonderful but I am really afraid he will at times be deficient in caution and prudence, and lay himself open to imposition, as well as incur much expense, perhaps sometimes unnecessarily."

Falconbridge also gave evidence to a privy council committee, and underwent four days of questions by a House of Commons committee. He explained how badly the slaves were treated on the ships: "The men, on being brought aboard the ship, are immediately fastened together, two and two, by handcuffs on their wrists and by irons rivetted on their legs. They are then sent down between the decks and placed in an apartment partitioned off for that purpose.... They are frequently stowed so close, as to admit of no other position than lying on their sides. Nor will the height between decks, unless directly under the grating, permit the indulgence of an erect posture; especially where there are platforms, which is generally the case. These platforms are a kind of shelf, about eight or nine feet in breadth, extending from the side of the ship toward the centre. They are placed nearly midway between the decks, at the distance of two or three feet from each deck, Upon these the Negroes are stowed in the same manner as they are on the deck underneath."

Clarkson attempted to show that the slave trade was highly dangerous. He claimed that of 5,000 sailors on the triangular route in 1786, 2,320 came home, 1,130 died, 80 were discharged in Africa and unaccounted for and 1,470 were discharged or deserted in the West Indies. Clarkson claimed that in Liverpool alone, over 15,165 seaman had been lost since 1771 in the 1,001 ships that had sailed from there to the coast of Africa.

Hugh Brogan has pointed out that in the pamphlet Clarkson argued that "far from being the nursery of British seamen, as its friends asserted, was in fact its graveyard, more seamen dying in that trade in one year than in the whole remaining trade of the country in two, and in the argument that slaves were not a necessary commodity for a flourishing trade with Africa."

Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997), has argued: "When on 24 May 1787 Clarkson, the heart and soul of the campaign for abolition, presented the Committee for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade with evidence on the unprofitability of the business, he used rational arguments: an end of the traffic would save the lives of seamen (he had obtained much detail from a scrutiny of Liverpool customs records), encourage cheap markets for the raw materials needed by industry, open new opportunities for British goods, eliminate a wasteful drain of capital, and inspire in the colonies a self-sustaining labour force, which in time would want to import more British produce."

Clarkson approached Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the anti-slavery group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it."

Wilberforce agreed that while people such as Thomas Clarkson worked on gathering evidence and mobilizing public opinion through the committee for the abolition of the slave trade, Wilberforce complemented their work through his exertions in the House of Commons. He also attempted lobbied bishops and prominent laymen. On 28th October, 1787, he wrote in his journal that "God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners".

Charles Fox was also unsure of Wilberforce's commitment to the anti-slavery campaign. He wrote to Thomas Walker: "There are many reasons why I am glad (Wilberforce) has undertaken it rather than I, and I think as you do, that I can be very useful in preventing him from betraying the cause, if he should be so inclined, which I own I suspect. Nothing, I think but such a disposition, or a want of judgment scarcely credible, could induce him to throw cold water upon petitions. It is from them and other demonstrations of the opinion without doors that I look for success."

Political radicals such as Francis Place hated politicians such as Wilberforce "for their complacency and indifference to poverty in their own country while fighting against the same thing abroad". He described him as "an ugly epitome of the devil". William Hazlitt added: "He preaches vital Christianity to untutored savages, and tolerates its worst abuses in civilised states. He thus shows his respect for religion without offending the clergy."

In May 1788, Charles Fox precipitated the first parliamentary debate on the issue. He denounced the "disgraceful traffic" which ought not to be regulated but destroyed. William Dolben described shipboard horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stowed like "herrings in a barrel" and stricken with "putrid and fatal disorders" which infected crews as well. With the support of Wilberforce Samuel Whitbread, Charles Middleton and William Smith, Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. The legislation was initially rejected by the House of Lords but after William Pitt threatened to resign as prime minister, the bill passed 56 to 5 and received royal assent on 11th July.

Wilberforce's biographer, John Wolffe, has argued: "Following the publication of the privy council report on 25 April 1789, Wilberforce marked his own delayed formal entry into the parliamentary campaign on 12 May with a closely reasoned speech of three and a half hours, using its evidence to describe the effects of the trade on Africa and the appalling conditions of the middle passage. He argued that abolition would lead to an improvement in the conditions of slaves already in the West Indies, and sought to answer the economic arguments of his opponents. For him, however, the fundamental issue was one of morality and justice. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was very pleased with the speech and sent its thanks for his "unparalleled assiduity and perseverance".

The House of Commons agreed to establish a committee to look into the slave trade. Wilberforce said he did not intend to introduce new testimony as the case against the trade was already in the public record. Ellen Gibson Wilson, a leading historian on the slave trade has argued: "Everyone thought the hearing would be brief, perhaps one sitting. Instead, the slaving interests prolonged it so skilfully that when the House adjourned on 23 June, their witnesses were still testifying."

In 1789 Thomas Clarkson published a drawing of the slave-ship, The Brookes. It was originally built to to carry a maximum of 451 people, but was carrying over 600 slaves from Africa to the Americas. "Chained together by their hands and feet, the slaves had little room to move." It has been claimed that the "startling diagram was distributed far and wide and prints hung in every abolitionist home."

Copies of this drawing was sent to members of the House of Commons committee to look into the issue of the slave trade. Thomas Trotter, a physician working on the slave-ship, Brookes, told the committee: "The slaves that are out of irons are locked spoonways and locked to one another. It is the duty of the first mate to see them stowed in this manner every morning; those which do not get quickly into their places are compelled by the cat and, such was the situation when stowed in this manner, and when the ship had much motion at sea, they were often miserably bruised against the deck or against each other. I have seen their breasts heaving and observed them draw their breath, with all those laborious and anxious efforts for life which we observe in expiring animals subjected by experiment to bad air of various kinds."

James Ramsay, the veteran campaigner against the slave trade, was now extremely ill. He wrote to Thomas Clarkson: "Whether the bill goes through the House or not, the discussion attending it will have a most beneficial effect. The whole of this business I think now to be in such a train as to enable me to bid farewell to the present scene with the satisfaction of not having lived in vain." Ten days later Ramsay died from a gastric haemorrhage. The vote on the slave trade was postponed to 1790.

William Wilberforce initially welcomed the French Revolution as he believed that the new government would abolish the country's slave trade. He wrote to Abbé de la Jeard on 17th July 1789 commenting that "I sympathize warmly in what is going forward in your country." Clarkson commented: "Mr. Wilberforce, always solicitous for the good of this great cause, was of the opinion that, as commotions have taken place in France, which then aimed at political reforms, it was possible that the leading persons concerned in them might, if an application were made to them judiciously, be induced to take the slave trade into their consideration, and incorporated among the abuses to be done away."

Wilberforce intended to visit France but he was persuaded by friends that it would be dangerous for an English politician to be in the country during a revolution. Wilberforce therefore asked Clarkson to visit Paris on behalf of himself and the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Clarkson was welcomed by the French abolitionists and later that month the government published A Declaration of the Rights of Man asserting that all men were born and remained free and equal.

However, the visit was a failure as Thomas Clarkson could not persuade the French National Assembly to discuss the abolition of the slave trade. Marquis de Lafayette said "he hoped the day was near at hand, when two great nations, which had been hitherto distinguished only for their hostility would unite in so sublime a measure (abolition) and that they would follow up their union by another, still more lovely, for the preservation of eternal and universal peace." Clarkson thought Lafayette "as uncompromising an enemy of the slave-trade and slavery, as any man I ever knew".

On his return to England, Thomas Clarkson continued to gather information for the campaign against the slave-trade. Over the next four months he covered over 7,000 miles. During this period he could only find twenty men willing to testify before the House of Commons. He later recalled: "I was disgusted... to find how little men were disposed to make sacrifices for so great a cause." There were some seamen who were willing to make the trip to London. One captain told Clarkson: "I had rather live on bread and water, and tell what I know of the slave trade, than live in the greatest affluence and withhold it."

Wilberforce believed that the support for the French Revolution by the leading members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade was creating difficulties for his attempts to bring an end to the slave trade in the House of Commons. He told Thomas Clarkson: "I wanted much to see you to tell you to keep clear from the subject of the French Revolution and I hope you will." Wilberforce had changed his views on the subject because of the way that radicals such as Thomas Paine had welcomed the French Revolution.

Wilberforce's conservative friends were also very concerned about the other leaders of the anti-slavery movement. Isaac Milner, a leader of the Clapham Set, had a long talk with Clarkson, and then commented to Wilberforce: "I wish him better health, and better notions in politics; no government can stand on such principles as he maintains. I am very sorry for it, because I see plainly advantage is taken of such cases as his, in order to represent the friends of Abolition as levellers."

Jonas Hanway established the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. This was an attempt to help black people living in London who had been victims of the slave trade. Simon Schama has argued in Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and Empire (2005) that the harsh winter of 1785-86 was one of the factors that encouraged Hanway to do something for the significant number of Africans living in poverty: "In the East End and Rotherhithe: tattered bundles of human misery, huddled in doorways, shoeless, sometimes shirtless even in the bitter cold or else covered with filthy rags."

Granville Sharp came up with the idea that a black community should be allowed to to start a colony of free slaves in Sierra Leone. The country was chosen largely on the strength of evidence from the explorer, Mungo Park and a encouraging report from the botanist, Henry Smeathman, who had recently spent three years in the area. The British government supported Sharp's plan and agreed to give £12 per African towards the cost of transport. Sharp contributed more than £1,700 to the venture. Thomas Clarkson was one of those who provided money for this venture.

Richard S. Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has argued: "Some detractors have since denounced the Sierra Leone project as repatriation by another name. It has been seen as a high-minded yet hypocritical way of ridding the country of its rising black population... Some in Britain wanted Africans to leave because they feared they were corrupting the virtues of the country's white women, while others were tired of seeing them reduced to begging on London streets."

Granville Sharp was able to persuade a small group of London's poor to travel to Sierra Leone. As Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997), has pointed out: "A ship was charted, the sloop-of-war Nautilus was commissioned as a convoy, and on 8th April the first 290 free black men and 41 black women, with 70 white women, including 60 prostitutes from London, left for Sierra Leone under the command of Captain Thomas Boulden Thompson of the Royal Navy". When they arrived they purchased a stretch of land between the rivers Sherbo and Sierra Leone.

The settlers sheltered under old sails, donated by the navy. They named the collection of tents Granville Town after the man who had made it all possible. Granville Sharp wrote to his brother that "they have purchased twenty miles square of the finest and most beautiful country... that was ever seen... fine streams of fresh water run down the hill on each side of the new township; and in the front is a noble bay."

The reality was very different. Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has argued: "The expedition's delayed departure from England meant that it had arrived on the African coast in the midst of the malarial rainy season.... The ground was another major problem: steep, forested slopes with thin topsoil... When they managed to coax a few English vegetables out of the ground, ants promptly devoured the leaves."

Soon after arriving the colony suffered from an outbreak of malaria. In the first four months alone, 122 died. One of the white settlers wrote to Sharp: "I am very sorry indeed, to inform you, dear Sir, that... I do not think there will be one of us left at the end of a twelfth month... There is not a thing, which is put into the ground, will grow more than a foot out of it... What is more surprising, the natives die very fast; it is quite a plague seems to reign here among us."

On 18th April 1791 Wilberforce introduced a bill to abolish the slave trade. William Wilberforce was supported by William Pitt, William Smith, Charles Fox, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, William Grenville and Henry Brougham. The opposition was led by Lord John Russell and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the MP for Liverpool. There was no reasoned justification of slavery or the slave-trade. Thomas Grosvenor, the MP for Chester, acknowledged that it was "not an amiable trade but neither was the trade of a butcher an amiable trade, and yet a mutton chop was, nevertheless, a good thing." One observer commented that it was "a war of the pigmies against the giants of the House". However, on 19th April, the motion was defeated by 163 to 88.

Granville Sharp came up with the idea that the black community in London should be allowed to to start a colony in Sierra Leone. The country was chosen largely on the strength of evidence from the explorer, Mungo Park and a encouraging report from the botanist, Henry Smeathman, who had recently spent three years in the area. The British government supported Sharp's plan and agreed to give £12 per African towards the cost of transport. Sharp contributed more than £1,700 to the venture. In the summer and autumn 1791 Wilberforce worked with his close friend Henry Thornton to launch the company.

Richard S. Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has argued: "Some detractors have since denounced the Sierra Leone project as repatriation by another name. It has been seen as a high-minded yet hypocritical way of ridding the country of its rising black population... Some in Britain wanted Africans to leave because they feared they were corrupting the virtues of the country's white women, while others were tired of seeing them reduced to begging on London streets."

Thomas Clarkson was close friends with William Buck, a prosperous yarnmaker at Bury St Edmunds. He became acquainted with his daughter, Catherine Buck, in 1792. Clarkson was 32 and Catherine was only 20. According to one friend she had "dark bright eyes twinkling in her delicate mobile face which smiled all over." Ellen Gibson Wilson argues that: "She was a vivacious young woman, a gifted conversationalist... She was popular in West Suffolk ballrooms but prized as much for her wit as her beauty."

Henry Crabb Robinson, was one of her close friends when she was a young woman. He later recalled that she had a strong interest in politics and loved to discuss the main issues of the day: "Her excellence lay rather in felicity of expression than in originality of thought. She was the most eloquent woman I have ever known, with the exception of Madame de Stael. She had a quick apprehension of every kind of beauty, and made her own whatever she learned."

Clarkson married Catherine at St. Mary's Church at Bury St Edmunds on 21st January 1796 and they went to live on his small estate at Eusemere on Ullswater. He renounced his Anglican orders, but although most of his political friends were Quakers, he decided against joining the Society of Friends. However, he attending the Penrith Quaker Meeting House and his wife, who in the past had been a free-thinker, read the works of George Fox. A friend commented: "She is become a religionist and a believer. Her faith receives little or no aid from written revelation - but God has spoken to her heart in a most sublime and mystical manner. In short she is of a species of Quaker."

In his book, The Great White Lie (1973), Jack Gratus argues that: "Clarkson... a large, rugged man, he was impatient and aggressive in manner with little sense of humour. He spoke as he wrote, ploddingly and pedantically, and both his readers and his acquaintances found he could be boring. His wife, in contrast, was a brilliant conversationalist and an excellent hostess."

Clarkson's biographer, Hugh Brogan, has argued that "Clarkson's health was collapsing, and he had spent more than half his small capital in the cause of abolition. He decided to retire from the work; led by Wilberforce his friends raised £1500 in 1794 to compensate him for his disbursements."

William Wilberforce wrote to one friend: "The truth is he has expended a considerable part of his little fortune, and though not perhaps very prudently or even necessarily yet I think, judging liberally, that he who has sacrificed so much time, and strength, and talents, should not be suffered to be out of pocket too. We should not look for inconsistent good qualities in the generality of men. Clarkson is ardent, earnest, and indefatigable, and we have benefited greatly from his exertions."

On his farm at Eusemere Clarkson grew wheat, oats, barley, red clover and turnips and pastured sheep and cows. He sold his produce at Penrith market. He became fascinated with farming. He wrote in his journal: "The bud and the blossom, the rising and the falling leaf, the blade of corn and the ear, the seed-time and the harvest, the sun that warms and ripens, the cloud that cools, and emits the fruitful shower, these and a hundred objects afford daily food for the religious growth of the mind."

In November 1799 William Wordsworth, Dorothy Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge visited the Clarksons at Eusemere. The following month the Wordsworths moved into the Town End cottage at Grasmere. The two couples regularly visited each other. Catherine was quick to see Wordsworth's talent. She wrote: "I am fully convinced that Wordsworth's genius is equal to the production of something very great, and I have no doubt that he will produce something that posterity will not willingly let die, if he lives ten or twenty years longer."

Robert Southey was also a regular visitor to the Clarkson's home. He later wrote that Clarkson was a "man who so nobly came forward about the Slave Trade to the ruin of his health - or rather state of mind - and to the deep injury of his fortune...It agitates him to talk about the subject (slave trade) - but when he does - he agitates every one who hears him." Samuel Taylor Coleridge commented: "He has never more than one thought in his brain at a time, let it be great or small. I have called him the moral steam-engine, or the Giant with one idea."

In March 1796, Wilberforce's proposal to abolish the slave trade was defeated in the House of Commons by only four votes. At least a dozen abolitionist MPs were out of town or at the new comic opera in London. Thomas Clarkson commented: "To have all our endeavours blasted by the vote of a single night is both vexatious and discouraging." Wilberforce wrote in his diary: "Enough at the Opera to have carried it. Very much vexed and incensed at our opponents".

William Wilberforce held conservative views on most other issues. He opposed parliamentary reform and supported the suspension of Habeas Corpus that resulted in political activists such as Thomas Hardy and John Thelwall being imprisoned. He also supported the government when it passed Combination Acts of 1799–1800. This made it illegal for workers to join together to press their employers for shorter hours or may pay. As a result trade unions were thus effectively made illegal.

In 1804 Thomas Clarkson returned to his campaign against the slave trade and toured the country on horseback obtaining new evidence and maintaining support for the campaigners in Parliament. A new generation of activists such as Henry Brougham, Zachary Macaulay and James Stephen, helped to galvanize older members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

William Wilberforce introduced an abolition bill on 30th May 1804. It passed all stages in the House of Commons and on 28th June it moved to the House of Lords. The Whig leader in the Lords, Lord Grenville, said as so many "friends of abolition had already gone home" the bill would be defeated and advised Wilberforce to leave the vote to the following year. Wilberforce agreed and later commented "that in the House of Lords a bill from the House of Commons is in a destitute and orphan state, unless it has some peer to adopt and take the conduct of it".

In February 1805, Wilberforce presented his eleventh abolition bill to the House of Commons. Charles Brooke reported that the French slave trade was resurgent, so that abolition would merely hand British commerce over to the enemy. Wilberforce replied: "The opportunity now offered may never return, and if the present moment be neglected, events may occur which render the whole of the West India islands one general scene of devastation and horror. The storm is fast gathering; every instant it becomes blacker and blacker. Even now I know not whether it be too late to avert the impending evil, but of this I am quite sure - that we have no time to lose." This time the pro-slave trade MPs were better organised and it was defeated by seven votes.

In February, 1806 Lord Grenville was invited by the king to form a new Whig administration. Grenville, was a strong opponent of the slave trade. Grenville was determined to bring an end to British involvement in the trade. He had spoken against the slave-trade in nearly all the debates in the 1790s. Thomas Clarkson sent a circular to all supporters of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade claiming that "we have rather more friends in the Cabinet than formerly" and suggested "spontaneous" lobbying of MPs. He added: "There was never perhaps a season when so much virtuous feeling pervading all ranks."

Grenville's Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, led the campaign in the House of Commons to ban the slave trade in captured colonies. Clarkson commented that Fox was "determined upon the abolition of it (the slave trade) as the highest glory of his administration, and as the greatest earthly blessing which it was the power of the Government to bestow." Wilberforce praised the new, younger, members of Parliament "whose lofty and liberal sentiments... show to the people that their legislators, and especially the higher order of their youth, are forward to assert the rights of the weak against the strong." (55)

This time there was little opposition to Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed by an overwhelming 114 to 15. In the House of Lords Lord Greenville made a passionate speech that lasted three hours where he argued that the trade was "contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy" and criticised fellow members for "not having abolished the trade long ago". Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "Lord Grenville ... opposed a delaying inquiry but several last-ditch petitions came from West Indian, London and Liverpool shipping and planting spokesmen.... He was determined to succeed and his canvassing of support had been meticulous." When the vote was taken the bill was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20. (56)

In 1807 Clarkson published his book History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade. He dedicated it to the nine of the twelve members of Lord Grenville's Cabinet who supported the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act and to the memories of William Pitt and Charles Fox. Clarkson played a generous tribute to the work of William Wilberforce: "For what, for example, could I myself have done if I had not derived so much assistance from the committee? What could Mr Wilberforce have done in parliament, if I ... had not collected that great body of evidence, to which there was such a constant appeal? And what could the committee have done without the parliamentary aid of Mr Wilberforce?"

In July, 1807, members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade established the African Institution, an organization that was committed to watch over the execution of the law, seek a ban on the slave trade by foreign powers and to promote the "civilization and happiness" of Africa. The Duke of Gloucester became the first president and members of the committee included Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, Henry Brougham, James Stephen, Granville Sharp and Zachary Macaulay. The banker, Henry Thornton, became treasurer.

Wayne Ackerson, the author of The African Institution and the Antislavery Movement in Great Britain (2005) has argued: "The African Institution was a pivotal abolitionist and antislavery group in Britain during the early nineteenth century, and its members included royalty, prominent lawyers, Members of Parliament, and noted reformers such as William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, and Zachary Macaulay. Focusing on the spread of Western civilization to Africa, the abolition of the foreign slave trade, and improving the lives of slaves in British colonies, the group's influence extended far into Britain's diplomatic relations in addition to the government's domestic affairs. The African Institution carried the torch for antislavery reform for twenty years and paved the way for later humanitarian efforts in Great Britain."

The African Institution complained about the negative view of Africans promoted by newspapers and books: "The portrait of the negro has seldom been drawn but by the pencil of his oppressor, and he has sat for it in the distorted attitude of slavery. If he be accused of brutal stupidity by one of those prejudiced witnesses, another taxes him with the most refined dissimulation and the most ingenious methods of deceit. If the negroes are represented as base and cowardly, they are in the same volume exhibited as braving death in the most hideous forms... Insensibility and excessive passion, apathy and enthusiasm, want of natural affection, and a fond attachment to their friends... are all ascribed to them by the same inconsistent pens."

The establishment never forgave Clarkson for his work against the slave-trade. The Edinburgh Review reported: "It is impossible to look into any of Mr Clarkson's books without feeling that he is an excellent man - and a very bad writer... Feeling in himself not only an entire toleration of honest tediousness, but a decided preference for it upon all occasions ... he seems to have ... forgotten, that though dullness may be a very venial fault in a good man, it is such a fault in a book as to render its goodness of no avail whatsoever.... With all his philanthropy, piety, and inflexible honesty, he has not escaped the sin of tediousness - and that to a degree that must render him almost illegible to any but Quakers, reviewers, and others who make public profession of patience insurmountable. He has no taste, and no spark of vivacity - not the vestige of an ear for harmony - and a prolixity of which modern times have scarcely preserved any other example.... He has great industry - scrupulous veracity - and that serious and sober enthusiasm for his subject, which is in the long-run to disarm ridicule.... above all, he is perfectly free from affectation; so that, though we may be wearied, we are never disturbed or offended - and read on, in tranquility, till we find it impossible to read any more."

William Wilberforce now spent his energies developing the Sierra Leone Company as a foundation for disseminating Christianity and civilization in Africa. It has been argued by Stephen Tomkins that during this period "Wilberforce... allowed the abolitionist colony of Sierra Leone... to use slave labour and buy and sell slaves.... After abolition, the British navy patrolled the Atlantic seizing slave ships. The crew were arrested, but what to do with the African captives? With the knowledge and consent of Wilberforce and friends, they were taken to Sierra Leone and put to slave labour in Freetown. They were called 'apprentices', but they were slaves. The governor of Sierra Leone paid the navy a bounty per head, put some of the men to work for the government, and sold the rest to landowners. They did forced labour, under threat of punishment, without pay, and those who escaped to neighbouring African villages to work for wages were arrested and brought back".

Ellen Gibson Wilson, the author of Thomas Clarkson (1989), has commented: "Clarkson in his prime was a handsome - some said majestic - figure, more than six feet tall with bold features and large, very blue and candid eyes. When he entered public life he wore a modish short and curled powdered wig, later his own thick and tousled hair which changed from red to white just as his face developed the furrows of care and conflict. He dressed habitually in black. In society, he made some people uncomfortable for he had little small talk and frequently withdrew into his own dark thoughts."

It gradually became clear that there were serious problems with the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. In fact, the situation became worse. Now that the supply had officially ceased, the demand grew and with it the price of slaves. For high prices the traders were prepared to take the additional risks. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea.

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. A new Anti-Slavery Society was formed in 1823 by Thomas Clarkson, Henry Brougham and Thomas Fowell Buxton. "Its purpose was to rouse public opinion to bring as much pressure as possible on parliament, and the new generation realized that for this they still needed Clarkson.... He rode some 10,000 miles and achieved his masterpiece: by the summer of 1824, 777 petitions had been sent to parliament demanding gradual emancipation".

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign such as Thomas Fowell Buxton, argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. "I now regret that I and those honourable friends who thought with me on this subject have not before attempted to put an end, not merely to the evils of the slave trade, but to the evils of slavery itself."

William Wilberforce disagreed, he believed that at this time slaves were not ready to be granted their freedom. He pointed out in A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Addressed to the Freeholders and other inhabitants of Yorkshire that: "It would be wrong to emancipate (the slaves). To grant freedom to them immediately, would be to insure not only their masters' ruin, but their own. They must (first) be trained and educated for freedom."

In 1823 Wilberforce published his Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies. "In this pamphlet he dwelt on the moral and spiritual degradation of the slaves and presented their emancipation as a matter of national duty to God. It proved to be a powerful inspiration for the anti-slavery agitation in the country."

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations.

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders like Wilberforce. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods".

The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak on the same platforms as Heyrick and other women who favoured an immediate end to slavery. His biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain".

Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture".

Thomas Clarkson was much more sympathetic towards women. Unusually for a man of his day, he believed women deserved a full education and a role in public life and admired the way the Quakers allowed women to speak in their meetings. Clarkson told Elizabeth Heyrick's friend, Lucy Townsend, that he objected to the fact that "women are still weighed in a different scale from men... If homage be paid to their beauty, very little is paid to their opinions."

Records show that about ten per cent of the financial supporters of the organisation were women. In some areas, such as Manchester, women made up over a quarter of all subscribers. Lucy Townsend asked Thomas Clarkson how she could contribute in the fight against slavery. He replied that it would be a good idea to establish a women's anti-slavery society.

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions."

In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. Elizabeth Heyrick, who was treasurer of the organisation suggested a new strategy to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue. In April 1830 they decided that the group would only give their annual £50 donation to the national anti-slavery society only "when they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title." At the national conference the following month, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. It also agreed to support Female Society's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition.

Wilberforce, who had always been reluctant to campaign against slavery, agreed to promote the organisation. Clarkson praised Wilberforce for taking this brave move. He replied: "I cannot but look back to those happy days when we began our labours together; or rather when we worked together - for he began before me - and we made the first step towards that great object, the completion of which is the purpose of our assembling this day."

Clarkson redoubled his efforts and between October 1830 and April 1831, 5,484 petitions calling for an end to slavery was sent to Parliament. However, Clarkson had to wait until 1833 before Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act that gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. It contained two controversial features: a transitional apprenticeship period and compensation to owners totalling £20,000,000. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned.

William Wilberforce died on 29th July 1833 at 44 Cadogan Place, Sloane Street. The following year Robert Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce, began work on their father's biography. The book was published in 1838. As Ellen Gibson Wilson, the author of Thomas Clarkson (1989), pointed out: "The five volumes which the Wilberforces published in 1838 vindicated Clarkson's worst fears that he would be forced to reply. How far the memoir was Christian, I must leave to others to decide. That it was unfair to Clarkson is not disputed. Where possible, the authors ignored Clarkson; where they could not they disparaged him. In the whole rambling work, using the thousands of documents available to them, they found no space for anything illustrating the mutual affection and regard between the two great men, or between Wilberforce and Clarkson's brother."

Wilson goes on to argue that the book has completely distorted the history of the campaign against the slave-trade: "The Life has been treated as an authoritative source for 150 years of histories and biographies. It is readily available and cannot be ignored because of the wealth of original material it contains. It has not always been read with the caution it deserves. That its treatment of Clarkson, in particular, a deservedly towering figure in the abolition struggle, is invalidated by untruths, omissions and misrepresentations of his motives and his achievements is not understood by later generations, unfamiliar with the jealousy that motivated the holy authors. When all the contemporary shouting had died away, the Life survived to take from Clarkson both his fame and his good name. It left us with the simplistic myth of Wilberforce and his evangelical warriors in a holy crusade".

Eventually, Robert Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce apologized for what they had done to Clarkson: "As it is now several years since the conclusion of all differences between us, and we can take a more dispassionate view than formerly of the circumstances of the case, we think ourselves bound to acknowledge that we were in the wrong in the manner in which we treated you in the memoir of our father.... we are conscious that too jealous a regard for what we thought our father's fame, led us to entertain an ungrounded prejudice against you and this led us into a tone of writing which we now acknowledge was practically unjust."

On 9th March 1837 Clarkson's son, was thrown out of his gig and killed instantly. His wife wrote to Henry Crabb Robinson: "It is true that under the infliction of so sudden and so sharp a blow I was at first incapable of receiving consolation from any earthly source." At the inquest it was discovered that a woman "not of good character" had been with him in the gig. A sum of £7 was distributed to keep this information out of the newspapers.

Clarkson was painted by Benjamin Haydon in 1840. "Though Clarkson is a gentleman by birth and was educated like one, he is too natural for any artifice. He says what he thinks, does what he feels inclined, is impatient, childish, simple - hungry and will eat, restless and will let you see it; punctual and will hurry, nervous and won't be hurried, positive and hates contradiction, charitable, speaks affectionately of all, even of Wilberforce's sons, whose abominable conduct he lamented, more as if it cast a shadow over the father's tomb, than as if he felt wounded from what they had falsely said of himself."

Thomas Clarkson's last few years were troubled by failing eyesight. He died at Playford Hall, near Ipswich on 26th September 1846. Alone among the leading abolitionists he was not immediately commemorated in Westminster Abbey. It is believed this was because of his closeness to the Society of Friends.

On this day in 1854 France and Britain declare war on Russia and begin the Crimean War. In July 1853 Russia occupied territories in the Crimea that had previously been controlled by Turkey. Britain and France was concerned about Russian expansion and attempted to achieve a negotiation withdrawal. Turkey, unwilling to grant concessions declared war on Russia.

After the Russians destroyed the Turkish fleet at Sinope in the Black Sea in November 1853, Britain and France joined the war against Russia. On the 20th September 1854 the Allied army defeated the Russian army at the battle of Alma River (September 1854) but the battle of Balaklava (October 1854) was inconclusive.

John Thadeus Delane, the editor of The Times, sent William Howard Russell to cover the Crimean War. He left London on 23rd February 1854. After spending time with the army in Gallipoli and Varna, he reported the battles and the Siege of Sevastopol. He found Lord Raglan uncooperative and wrote to Delane alleging unfairly that "Lord Raglan is utterly incompetent to lead an army".

Roger T. Stearn has argued: "Unwelcomed and obstructed by Lord Raglan, senior officers (except de Lacy Evans), and staff, yet neither banned, controlled, nor censored, Russell made friends with junior officers, and from them and other ranks, and by observation, gained his information. He wore quasi-military clothes and was armed, but did not fight. He was not a great writer but his reports were vivid, dramatic, interesting, and convincing.... His reports identified with the British forces and praised British heroism. He exposed logistic and medical bungling and failure, and the suffering of the troops."

His reports revealled the sufferings of the British Army during the winter of 1854-1855. These accounts upset Queen Victoria who described them as these "infamous attacks against the army which have disgraced our newspapers". Prince Albert, who took a keen interest in military matters, commented that "the pen and ink of one miserable scribbler is despoiling the country." Lord Raglan complained that Russell had revealed military information potentially useful to the enemy.

William Howard Russell reported that British soldiers began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases. When Mary Seacole heard about the cholera epidemic she travelled to London to offer her services to the British Army. There was considerable prejudice against women's involvement in medicine and her offer was rejected. When Russell publicised the fact that a large number of soldiers were dying of cholera there was a public outcry, and the government was forced to change its mind. Florence Nightingale volunteered her services and was eventually given permission to take a group of thirty-eight nurses to Turkey.

Russell's reports led to attacks on the government by the the Liberal M.P. John Roebuck. He claimed that the British contingent had 23,000 men unfit for duty due to ill health and only 9,000 fit for duty. When Roebuck proposal for an inquiry into the condition of the British Army, the government was passed by 305 to 148. As a result the Earl of Aberdeen, resigned in January 1855. The Duke of Newcastle told Russell " It was you who turned out the government".

Florence Nightingale found the conditions in the army hospital in Scutari appalling. The men were kept in rooms without blankets or decent food. Unwashed, they were still wearing their army uniforms that were "stiff with dirt and gore". In these conditions, it was not surprising that in army hospitals, war wounds only accounted for one death in six. Diseases such as typhus, cholera and dysentery were the main reasons why the death-rate was so high amongst wounded soldiers.

Military officers and doctors objected to Nightingale's views on reforming military hospitals. They interpreted her comments as an attack on their professionalism and she was made to feel unwelcome. Nightingale received very little help from the military until she used her contacts at The Times to report details of the way that the British Army treated its wounded soldiers. John Delane, the editor of newspaper took up her cause, and after a great deal of publicity, Nightingale was given the task of organizing the barracks hospital after the battle of Inkerman and by improving the quality of the sanitation she was able to dramatically reduce the death-rate of her patients.

Although Mary Seacole was an expert at dealing with cholera, her application to join Florence Nightingale's team was rejected. Mary, who had become a successful business woman in Jamaica, decided to travel to the Crimea at her own expense. She visited Nightingale at her hospital at Scutari but once again Mary's offer of help was refused.

Unwilling to accept defeat, Mary Seacole started up a business called the British Hotel, a few miles from the battlefront. Here she sold food and drink to the British soldiers. With the money she earned from her business Mary was able to finance the medical treatment she gave to the soldiers.

Whereas Florence Nightingale and her nurses were based in a hospital several miles from the front, Mary Seacole treated her patients on the battlefield. On several occasions she was found treating wounded soldiers from both sides while the battle was still going on.

Sevastopol fell to the Allied troops on 8th September 1855 and the new Russian Emperor, Alexander II, agreed to sign a peace treaty at the Congress of Paris in 1856.

On this day in 1862 French politician Aristide Briand was born at Nantes, France. While a law student he developed socialist ideas and after leaving university wrote for Le Peuple, La Lanterne and Petite République.

Briand, became secretary-general of the French Socialist Party in 1901 and the following year was elected to Chamber of Deputies. In 1904 he joined with Jean Jaurés to establish the left-wing newspaper, L'Humanité in 1904.

In 1906 Briand was expelled from the party for accepting office in the coalition government headed by Georges Clemenceau. As minister of public instruction and worship (1906-09) Briand helped to complete the separation of Church and State in France.

In July 1909 Briand became prime minister and horrified his former socialist colleagues when he broke up a railway stoppage by calling up some of the strikers for military service. Briand further upset the left-wing by supporting the extension of compulsory military service. He lost power in November 1910 but returned to office briefly in 1913.

On the outbreak of the First World War Briand became Justice Minister in the French government headed by Rene Viviani. A powerful cabinet figure, Briand advocated French intervention on the Balkan Front and promoted the merits of the socialist general, Maurice Sarrail.

In October 1915, the French president, Raymond Poincare appointed Briand as prime minister. His attempts to establish political control over the military high command ended in failure and he was unable to persuade Joseph Joffre, chief of general staff in the French Army, to change his tactics on the Western Front. However, after French losses at Verdun Briand was able to remove Joffre from power.

Georges Clemenceau, editor of L'Homme Libre, became highly critical of Briand's decision not to persecute pacifists and his refusal to sack his interior minister, Louis Malvy, who favoured a negotiated peace.

Briand backed the Nivelle Offensive and when this failed, the resignation of Hubert Lyautey in November 1917, brought the government down. Briand was now replaced by his long-time rival, Georges Clemenceau, as prime minister.

Briand returned to power in 1921 and as well as being prime minister (1921-22, 1925-26 and 1929) he was also foreign minister between 1925 and 1932. While in this post he put forward the idea of a European Federal Union. He gained support from Edouard Herriot but the idea stimulated little interest and was not taken up by other political leaders.

Briand became a great supporter of international pacifism through the League of Nations. He also championed Franco-German reconciliation and in 1926 shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Gustav Stresemann. Two years later he and Frank. B. Kellogg signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact (Pact of Paris). The treaty outlawed war between France and the United States. The US Senate ratified it in 1929 and over the next few years forty-six nations signed a similar agreement committing themselves to peace.

Aristide Briand died in Paris on 7th March, 1932.

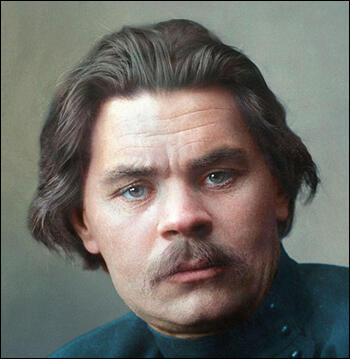

On this day in 1868 Russian novelist Maxim Gorky was born in Nizhny Novgorod. His father was a shipping agent but he died when Gorky was only five years old. His mother remarried and Gorky was brought up by his grandmother.

Gorky left home in 1879 and went to live in a small village in Kazan and worked as a baker. At this time radical groups such as the Land and Liberty group sent people into rural areas to educate the peasants. Gorky attended these meetings and it was during this period that Gorky read the works of Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Peter Lavrov , Alexander Herzen, Karl Marx and George Plekhanov. Gorky became a Marxist but he was later to say that was largely because of the teachings of the village baker, Vasilii Semenov.

In 1887 Gorky witnessed a Pogrom in Nizhny Novgorod. Deeply shocked by what he saw, Gorky became a life-long opponent of racism. Gorky worked with the Liberation of Labour group and in October, 1889 was arrested and accused of spreading revolutionary propaganda. He was later released because they did not have enough evidence to gain a conviction. However, the Okhrana decided to keep him under police surveillance.

Osip Volzhanin met Gorky in 1889: "He was tall, stooped, dressed in a coat-like jacket and high polished boots. His face was ordinary, plebeian, with a homely duck-like nose. By his appearance he could easily have been taken for a worker or a craftsman. The young man sat on the window sill, and swinging his long legs, spoke strongly emphasizing the letter 'O'. We listened with great delight to his stories, though Somov, an implacable 'political', disapproved of the stories and the behaviour of the young man. In his opinion, the latter occupied himself with trifles."

In 1891 Gorky moved to Tiflis where he found employment as a painter in a railway yard. The following year his first short-story, Makar Chudra, appeared in the Tiflis newspaper, Kavkaz. He story appeared under the name Maxim Gorky (Maxim the Bitter). The story was popular with the readers and soon others began appearing in other journals such as the successful Russian Wealth.

Gorky also began writing articles on politics and literature for newspapers. In 1895 he began writing a daily column under the heading, By the Way. In this articles he campaigned against the eviction of peasants from their land and the persecution of trade unionists in Russia. He also criticized the country's poor educational standards, the government's treatment of the Jewish community and the growth in foreign investment in Russia.

In his story Twenty-six Men and a Girl, one of his characters comment: “The poor are always rich in children, and in the dirt and ditches of this street there are groups of them from morning to night, hungry, naked and dirty. Children are the living flowers of the earth, but these had the appearance of flowers that have faded prematurely, because they grew in ground where there was no healthy nourishment.”

Gorky's short stories often showed Gorky's interest in social reform. In a letter to a friend, Gorky argued that "the aim of literature is to help man to understand himself, to strengthen the trust in himself, and to develop in him the striving toward truth; it is to fight meanness in people, to learn how to find the good in them, to awake in their souls shame, anger, courage; to do all in order that man should become nobly strong."

In 1898 Gorky published his first collection of short-stories. The book was a great success and he was now one of the country's most read and discussed writers. His choice of heroes and themes helped him emerge as the champion of the poor and the oppressed. The Okhrana became greatly concerned with Gorky's outspoken views, especially his articles and stories about the police, but his increasing popularity with the public made it difficult for them to take action against him.

Gorky secretly began helping illegal organizations such as the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Social Democratic Labour Party. He donated money to party funds and helped with the distribution of radical newspapers such as Iskra. One Bolsheviks later recalled that Gorky's contribution included "financial help systematically paid every month, technical assistance in the establishment of printing shops, organizing transport of illegal literature, arranging for meeting places, and supplying addresses of people who could be helpful."

On 4th March, 1901, Gorky witnessed a police attack on a student demonstration in Kazan. After publishing a statement attacking the way the police treated the demonstrators, Gorky was arrested and imprisoned. Gorky's health deteriorated and afraid he would die, the authorities released him after a month. He was put under house arrest, his correspondence was monitored and restrictions were placed on his movement around the country. When he was allowed to travel to the Crimea, he was greeted on the route by large crowds bearing banners with the words: "Long live Gorky, the bard of Freedom exiled without investigation or trial."

In 1902 Gorky was elected to the Imperial Academy of Literature. Nicholas II was furious when he heard the news and wrote to his Minister of Education: "Neither Gorky's age nor his works provide enough ground to warrant his election to such an honorary title. Much more serious is the circumstance that he is under police surveillance. And the Academy is allowing, in our troubled times, such a person to be elected! I am deeply dismayed by all this and entrust to you to announce that on my orders, the election of Gorky is to be cancelled."

When news that the Academy had followed the Tsar's orders and had overruled Gorky's election, several writers resigned in protest. Later that year the statutes of the Academy were changed, giving Nicholas II the power to approve the list of candidates before they came up for election.

Gorky gave his support to Father George Gapon and his planned march to the Winter Palace. He attended the march on the 22nd January, 1905, and that night Gapon stayed in his house. After Blood Sunday Gorky changed his mind about the moral right for revolutionaries to use violence. He wrote to a friend: "Two hundred black eyes will not paint Russian history over in a brighter colour; for that, blood is needed, much blood. Life has been built on cruelty and force. For its reconstruction, it demands cold calculated cruelty - that is all! They kill? It is necessary to do so! Otherwise what will you do? Will you go to Count Tolstoy and wait with him?"

After Blood Sunday Gorky was arrested and charged with inciting the people to revolt. Following a wide-world protest at Gorky's imprisonment in the Peter and Paul Fortress, Nicholas II agreed for him to be deported from Russia. Gorky now spent his time attempting to gain support for the overthrow of the Russian autocracy. This included raising money to buy arms for the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Social Democratic Labour Party. He also helped to fund the new Bolsheviks newspaper Novaya Zhizn.

In 1906 Gorky toured Europe and the United States. He arrived in New York on 28th March, 1906 and the New York Times reported that "the reception given to Gorky revealed with that of Kossuth and Garibaldi." His campaign tour was organized by a group of writers that included Ernest Poole, William Dean Howells, Jack London, Mark Twain, Charles Beard and Upton Sinclair.

The New York World newspaper decided to run a smear campaign against Gorky. The American public were shocked to hear that Gorky was staying in his hotel with a woman who was not his wife. The newspaper printed that the "so-called Mme Gorky who is not Mme Gorky at all, but a Russian actress Andreeva, with whom he has been living since his separation from his wife a few years ago." As a result of the story Gorky was evicted from his hotel and William Dean Howells and Mark Twain changed their mind about supporting his campaign. President Theodore Roosevelt also withdrew his invitation for Gorky to meet him in the White House.

Others such as H. G. Wells continued to help Gorky and issued a statement that included the comment: "I do not know what motive actuated a certain section of the American press to initiate the pelting of Maxim Gorky. A passion for moral purity ever before begot so brazen and abundant torrent of lies." Frank Giddings, a sociologist, compared the attack on Gorky to the lynching of three African Americans in Missouri. "Maxim Gorky came to this country not for the purpose of putting himself on exhibition, as many literary characters have done at one time or another, not for the purpose of lining his pockets with American gold, but for the purpose of obtaining sympathy and financial assistance for a people struggling against terrific odds, as the American people once struggled, for political and individual liberty. All was assertion, accusation, hysteria, impertinence in the way the papers have tried to instruct Gorky in morality."

Maxim Gorky also upset other supporters by sending a telegram of support to William Haywood, the leader of the Industrial Workers of the World, who was in prison waiting to be tried for the murder of the politician, Frank Steunenberg. Later Gorky published a book American Sketches, where he criticized the gross inequalities in American society. In one article he wrote that if anyone "wanted to become a socialist in a hurry, he should come to the United States."

In 1907 Gorky attended the Fifth Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party. While there he met Lenin, Julius Martov, George Plekhanov, Leon Trotsky and other leaders of the party. Gorky preferred Martov and the Mensheviks and was highly critical of Lenin's attempts to create a small party of professional revolutionaries. Gorky commented that he was not impressed with Lenin: "I did not expect Lenin to be like that. Something was lacking in him. He rolled his r's gutturally, and had a jaunty way of standing with his hands somehow poked up under his armpits. He was somehow too ordinary and did not give the impression of being a leader."

Gorky was later to write about Lenin: "Squat and solid, with a skull like Socrates and the all-seeing eyes of a great deceiver, he often liked to assume a strange and somewhat ludicrous posture: throw his head backwards, then incline it to the shoulder, put his hands under his armpits, behind the vest. There was in this posture something delightfully comical, something triumphantly cocky. At such moments his whole being radiated happiness. His movements were lithe and supple and his sparing but forceful gestures harmonized well with his words, also sparing but abounding in significance. From his face of Mongolian cast gleamed and flashed the eyes of a tireless hunter of falsehood and of the woes of life - eyes that squinted, blinked, sparkled sardonically, or glowered with rage. The glare of those eyes rendered his words more burning and more poignantly clear.... A passion for gambling was part of Lenin's character. But this was not the gambling of a self-centred fortune seeker. In Lenin it expressed that extraordinary power of faith which is found in a man firmly believing in his calling, one who is deeply and fully conscious of his bond with the world outside and has thoroughly understood his role in the chaos of the world, the role of an enemy of chaos."

Gorky continued to write and his most successful novels include Three of Them (1900), Mother (1906), A Confession (1908), Okurov City (1909) and the Life of Matvey Kozhemyakin (1910). Gorky argued: "The aim of literature is to help man to understand himself, to strengthen the trust in himself, and to develop in him the striving toward truth; it is to fight meanness in people, to learn how to find the good in them, to awake in their souls shame, anger, courage; to do all in order that man should become nobly strong."

Gorky was strongly opposed the First World War and he was attacked in the Russian press as being unpatriotic. In 1915 he established the political-literary journal, Letopis (Chronicle) and helped establish the Russian Society of the Life of the Jews, an organization that protested against the persecution of the Jewish community in Russia.

In March, 1917, Gorky welcomed the abdication of Nicholas II and supported the Provisional Government. Gorky wrote to his son: "We won not because we are strong, but because the government was weak. We have made a political revolution and have to reinforce our conquest. I am a social democrat, but I am saying and will continue to say, that the time has not come for socialist-style reforms."

With the support of the Mensheviks, Gorky started a newspaper, New Life, in 1917, and used it to attack the idea that the Bolsheviks were planning to overthrow the government of Alexander Kerensky. On 16th October, 1917, he called on Lenin to deny these rumours and show he was "capable of leading the masses, and not a weapon in the hands of shameless adventurers of fanatics gone mad."

After the October Revolution the new government got Joseph Stalin to lead the attack on Gorky. In the newspaper Workers' Road, Stalin wrote: "A whole list of such great names was discarded by the Russian Revolution. Plekhanov, Kropotkin, Breshkovskaia, Zasulich and all those revolutionaries who are distinguished only because they are old. We fear that Gorky is drawn towards them, into the archives. Well, to each his own. The Revolution neither pities nor buries its dead."

Gorky retaliated by writing in the New Life in 7th November, 1917. "Lenin and Trotsky and their followers already have been poisoned by the rotten venom of power. The proof of this is their attitude toward freedom of speech and of person and toward all the ideals for which democracy was fighting." Three days later Gorky called Lenin and Leon Trotsky the "Napoleons of socialism" who were involved in a "cruel experiment with the Russian people."

Victor Serge met Gorky during this period: "His apartment at the Kronversky Prospect, full of books, seemed as warm as a greenhouse. He himself was chilly even under his thick grey sweater, and coughed terribly, the result of his thirty years' struggle against tuberculosis. Tall, lean and bony, broad-shouldered and hollow-chested, he stooped a little as he walked. His frame, sturdily-built but anaemic, appeared essentially as a support for his head. An ordinary, Russian man in the street's head, bony and pitted, really almost ugly with its jutting cheek-bones, great thin-lipped mouth and professional smeller's nose, broad and peaked."

In January, 1918, Gorky led the attack on Lenin's decision to close down the Constituent Assembly. Gorky wrote in the New Life that the Bolsheviks had betrayed the ideals of generations of reformers: "For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished along with tens of thousands of workers and peasants."

The Bolshevik government controlled the distribution of newsprint and in July, 1918, it cut off supplies to New Life and Gorky was forced to close his newspaper. The government also took action making it impossible for Gorky to get his work published in Russia.

During the Civil War Gorky agreed to give his support to the Bolsheviks against the White Army. In return Lenin gave him permission to establish the publishing company, World Literature. This enabled Gorky to give employment to people such as Victor Serge and other critics of the Soviet government. Privately, Gorky remained an opponent of the government. In September, 1919, he wrote to Lenin: "for me it became clear that the "reds" are the enemies of the people just as the "whites". Personally, I of course would rather be destroyed by the "whites", but the "reds" are also no comrades of mine."

In 1921 Gorky once again clashed with the Soviet government over the suppression of the Kronstadt Uprising. Gorky blamed Gregory Zinoviev for the way the sailors were treated after the rebellion. Gorky failed to save the life of the writer, Nikolai Gumilev, who was arrested and executed for his support for the Kronstadt sailors. He was also unsuccessfully in obtaining an exit visa for the poet, Alexander Blok, who was dangerously ill. By the time Zinoviev gave permission for Blok to leave the country, he was dead.

Gorky based his play, The Plodder Slovotekov, on his experiences of dealing with Gregory Zinoviev. The play began its run on 18th June, 1921, but its criticism of the Soviet government's inefficient bureaucracy resulted in it being closed down after only three performances.