Cholera

Cholera was one of the most fatal diseases in the 19th century. Nausea and dizziness led to violent vomiting and diarrhoea, "with stools turning to a grey liquid until nothing emerged but water and fragments of intestinal membrane... extreme muscular cramps followed, with an insatiable desire for water". It is estimated that 16,000 people died during the 1831-1832 epidemic. (1)

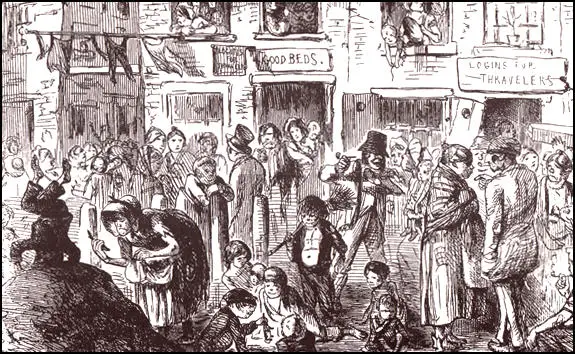

Only working-class people appeared to suffer from cholera. Stories began to circulate that doctors were spreading the disease as an excuse for getting their hands on corpses to dissect. Charles Greville, secretary to the Privy Council, noted in his diary: "The other day a Mr Pope, head of the cholera hospital in Marylebone, came to the Council Office to complain that a patient who was being removed to hospital with his own consent had been taken out of his chair by the mob and carried back, the chair broken, and the bearers and surgeon hardly escaping with their lives... In short, there is no end to the... uproar, violence, and brutal ignorance that have gone on, and this on the part of the lower orders, for whose especial benefit all the precautions are taken." (2)

Rioting broke out all over Britain. Crowds of men, women and children smashed windows at the Toxteth Park Cholera Hospital in Liverpool and pelted members of the local board of health with bricks. On 2nd September 1832, violence erupted in Manchester when a mob Swan Street Hospital, breaking down the gates and fighting a pitched battle with the police. This was as a result of a local man, John Hare, discovering that his grandson's body, who had died of cholera, had been smuggled out of the hospital by a doctor who wanted to dissect it. (3)

Public Health Act

After the 1847 General Election, Lord John Russell became leader of a new Liberal government. The government proposed a Public Health Bill. There were still a large number of MPs who were strong supporters of what was known as laissez-faire. This was a belief that government should not interfere in the free market. They argued that it was up to individuals to decide on what goods or services they wanted to buy. These included spending on such things as sewage removal and water supplies. George Hudson, the Conservative Party MP, stated in the House of Commons: "The people want to be left to manage their own affairs; they do not want Parliament... interfering in everybody's business." (4)

Supporters of Edwin Chadwick argued that many people were not well-informed enough to make good decisions on these matters. Other MPs pointed out that many people could not afford the cost of these services and therefore needed the help of the government. The Health of Towns Association, an organisation formed by Thomas Southwood Smith, began a propaganda campaign in favour of reform and encouraged people to sign a petition in favour of the Public Health Bill. In June 1847, the association sent Parliament a petition that contained over 32,000 signatures. However, this was not enough to persuade Parliament, and in July the bill was defeated. (5)

1848 Cholera Outbreak

A few weeks later news reached Britain of an outbreak of cholera in Egypt. The disease gradually spread west, and by early 1848 it had arrived in Europe. The previous outbreak of cholera in Britain in 1831, had resulted in the deaths of over 16,000 people. In his report, published in 1842, Chadwick had pointed out that nearly all these deaths had occurred in those areas with impure water supplies and inefficient sewage removal systems. Faced with the possibility of a cholera epidemic, the government decided to try again. This new bill involved the setting up of a Board of Health Act, that had the power to advise and assist towns which wanted to improve public sanitation. (6)

In an attempt to persuade the supporters of laissez-faire to agree to a Public Health Act, the government made several changes to the bill introduced in 1847. For example, local boards of health could only be established when more than one-tenth of the ratepayers agreed to it or if the death-rate was higher than 23 per 1000. Chadwick was disappointed by the changes that had taken place, but he agreed to become one of the three members of the central Board of Health when the act was passed in the summer of 1848. (7)

In 1849 cholera killed over 50,000 people. John Snow published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera where he argued against the theory of miasmatism (a belief that diseases are caused by noxious form of air emanating from rotting organic matter). He pointed out the disease affected the intestines not the lungs. Snow suggested the contamination of drinking water as a result of cholera evacuations seeping into wells or running into rivers. (8)

Broad Street Pump

In August 1854 cholera cases began to appear in Soho. Snow investigated all 93 local deaths. He concluded the local water supply had become contaminated, for nearly all the victims used water from the Broad Street pump. At a nearby prison, conditions were far worse, but few deaths. Snow concluded that this was because it had its own well. On 7th September he requested the parish Board of Guardians to disconnect the pump. Sceptical but desperate, they agreed and the handle was removed. After this very few cases were reported. (9)

In 1855, Snow gave his views to a House of Commons Select Committee set up to investigate cholera. Snow argued that cholera was not contagious nor spread by miasmata but was water-borne. He advocated the government invested in massive improvements in drainage and sewage. It has been claimed that his research "played some part in the investment by London and other major British cities in new main drainage and sewage systems." (10)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Greville, diary entry (1st April, 1832)

I have refrained for a long time from writing down anything about the cholera because the subject is intolerably disgusting to me, and I have been bored past endurance by the perpetual questions of every fool about it. It is not, however, devoid of interest. In the first place, what has happened here proves that the people of this enlightened, reading, thinking, reforming nation are not a whit less barbarous than the serfs in Russia, for precisely the same prejudices have been shown here that were found at St Petersburg and at Berlin.

The other day a Mr Pope, head of the cholera hospital in Marylebone, came to the Council Office to complain that a patient who was being removed to hospital with his own consent had been taken out of his chair by the mob and carried back, the chair broken, and the bearers and surgeon hardly escaping with their lives... In short, there is no end to the... uproar, violence, and brutal ignorance that have gone on, and this on the part of the lower orders, for whose especial benefit all the precautions are taken.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)