1917 Provisional Government in Russia

As Nicholas II was supreme command of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline in his support in Russia. George Buchanan, the British Ambassador in Russia, went to see the Tsar: "I went on to say that there was now a barrier between him and his people, and that if Russia was still united as a nation it was in opposing his present policy. The people, who have rallied so splendidly round their Sovereign on the outbreak of war, had seen how hundreds of thousands of lives had been sacrificed on account of the lack of rifles and munitions; how, owing to the incompetence of the administration there had been a severe food crisis."

Buchanan then went on to talk about Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna: "I next called His Majesty's attention to the attempts being made by the Germans, not only to create dissension between the Allies, but to estrange him from his people. Their agents were everywhere at work. They were pulling the strings, and were using as their unconscious tools those who were in the habit of advising His Majesty as to the choice of his Ministers. They indirectly influenced the Empress through those in her entourage, with the result that, instead of being loved, as she ought to be, Her Majesty was discredited and accused of working in German interests." (1)

The Provisional Government

In January 1917, General Aleksandr Krymov returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma. Krymov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. "A revolution is imminent and we at the front feel it to be so. If you decide on such an extreme step (the overthrow of the Tsar), we will support you. Clearly there is no other way." Rodzianko was unwilling to take action but he did telegraph the Tsar warning that Russia was approaching breaking point. He also criticised the impact that his wife was having on the situation and told him that "you must find a way to remove the Empress from politics". (2)

The Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich shared the views of Rodzianko and sent a letter to the Tsar: "The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs." (3)

The First World War was having a disastrous impact on the Russian economy. Food was in short supply and this led to rising prices. By January 1917 the price of commodities in Petrograd had increased six-fold. In an attempt to increase their wages, industrial workers went on strike and in Petrograd people took to the street demanding food. On 11th February, 1917, a large crowd marched through the streets of Petrograd breaking shop windows and shouting anti-war slogans.

Petrograd was a city of 2,700,000 swollen with an influx of of over 393,000 wartime workers. According to Harrison E. Salisbury, in the last ten days of January, the city had received 21 carloads of grain and flour per day instead of the 120 wagons needed to feed the city. Okhrana, the secret police, warned that "with every day the food question becomes more acute and it brings down cursing of the most unbridled kind against anyone who has any connection with food supplies." (4)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Daily Chronicle reported details of serious food shortages: "All attention here is concentrated on the food question, which for the moment has become unintelligible. Long queues before the bakers' shops have long been a normal feature of life in the city. Grey bread is now sold instead of white, and cakes are not baked. Crowds wander about the streets, mostly women and boys, with a sprinkling of workmen. Here and there windows are broken and a few bakers' shops looted." (5)

It was reported that in one demonstration in the streets by the Nevsky Prospect, the women called out to the soldiers, "Comrades, take away your bayonets, join us!". The soldiers hesitated: "They threw swift glances at their own comrades. The next moment one bayonet is slowly raised, is slowly lifted above the shoulders of the approaching demonstrators. There is thunderous applause. The triumphant crowd greeted their brothers clothed in the grey cloaks of the soldiery. The soldiers mixed freely with the demonstrators." On 27th February, 1917, the Volynsky Regiment mutinied and after killing their commanding officer "made common cause with the demonstrators". (6)

The President of the Duma, Michael Rodzianko, became very concerned about the situation in the city and sent a telegram to the Tsar: "The situation is serious. There is anarchy in the capital. The Government is paralysed. Transport, food, and fuel supply are completely disorganised. Universal discontent is increasing. Disorderly firing is going on in the streets. Some troops are firing at each other. It is urgently necessary to entrust a man enjoying the confidence of the country with the formation of a new Government. Delay is impossible. Any tardiness is fatal. I pray God that at this hour the responsibility may not fall upon the Sovereign." (7)

On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Arthur Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges." (8)

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working in Petrograd, with strong left-wing opinions, wrote to his aunt, Anna Maria Philips, claiming that the country was on the verge of revolution: "Most exciting times. I knew this was coming sooner or later but did not think it would come so quickly... Whole country is wild with joy, waving red flags and singing Marseillaise. It has surpassed my wildest dreams and I can hardly believe it is true. After two-and-half years of mental suffering and darkness I at last begin to see light. Long live Great Russia who has shown the world the road to freedom. May Germany and England follow in her steps." (9)

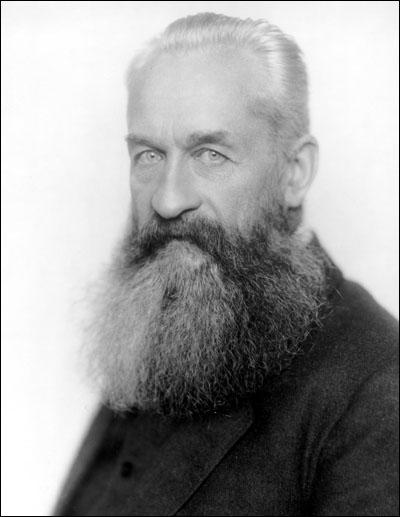

Prince George Lvov

On 10th March, 1917, the Tsar had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that Nicholas II should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed." (10)

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government. Members of the Cabinet included Pavel Milyukov (leader of the Cadet Party), was Foreign Minister, Alexander Guchkov, Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, Mikhail Tereshchenko, a beet-sugar magnate from the Ukraine, became Finance Minister, Alexander Konovalov, a munitions maker, Minister of Trade and Industry, and Peter Struve, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Prince Lvov had always held aloof from a purely political life. He belonged to no party, and as head of the Government could rise above party issues. Not till later did the four months of his premiership demonstrate the consequences of such aloofness even from that very narrow sphere of political life which in Tsarist Russia was limited to work in the Duma and party activity. Neither a clear, definite, manly programme, nor the ability for firmly and persistently realising certain political problems were to be found in Prince G. Lvov. But these weak points of his character were generally unknown." (11)

Prince George Lvov allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Joseph Stalin arrived at Nicholas Station in St. Petersburg with Lev Kamenev and Yakov Sverdlov on 25th March, 1917. The three men had been in exile in Siberia. Stalin's biographer, Robert Service, has commented: "He was pinched-looking after the long train trip and had visibly aged over the four years in exile. Having gone away a young revolutionary, he was coming back a middle-aged political veteran." (12)

The exiles discussed what to do next. The Bolshevik organizations in Petrograd were controlled by a group of young men including Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov who had recently made arrangements for the publication of Pravda, the official Bolshevik newspaper. The young comrades were less than delighted to see these influential new arrivals. Molotov later recalled: "In 1917 Stalin and Kamenev cleverly shoved me off the Pravda editorial team. Without unnecessary fuss, quite delicately." (13)

The Petrograd Soviet recognized the authority of the Provisional Government in return for its willingness to carry out eight measures. This included the full and immediate amnesty for all political prisoners and exiles; freedom of speech, press, assembly, and strikes; the abolition of all class, group and religious restrictions; the election of a Constituent Assembly by universal secret ballot; the substitution of the police by a national militia; democratic elections of officials for municipalities and townships and the retention of the military units that had taken place in the revolution that had overthrown Nicholas II. Soldiers dominated the Soviet. The workers had only one delegate for every thousand, whereas every company of soldiers might have one or even two delegates. Voting during this period showed that only about forty out of a total of 1,500, were Bolsheviks. Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries were in the majority in the Soviet.

The Provisional Government accepted most of these demands and introduced the eight-hour day, announced a political amnesty, abolished capital punishment and the exile of political prisoners, instituted trial by jury for all offences, put an end to discrimination based on religious, class or national criteria, created an independent judiciary, separated church and state, and committed itself to full liberty of conscience, the press, worship and association. It also drew up plans for the election of a Constituent Assembly based on adult universal suffrage and announced this would take place in the autumn of 1917. It appeared to be the most progressive government in history. (14)

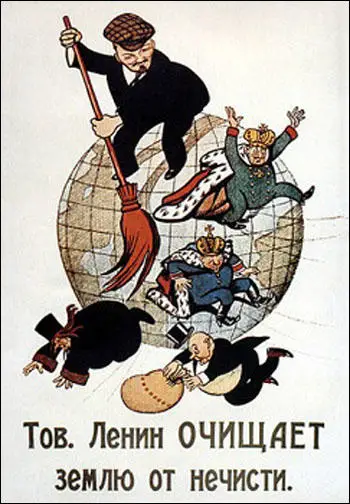

When Lenin returned to Russia on 3rd April, 1917, he announced what became known as the April Theses. As he left the railway station Lenin was lifted on to one of the armoured cars specially provided for the occasions. The atmosphere was electric and enthusiastic. Feodosiya Drabkina, who had been an active revolutionary for many years, was in the crowd and later remarked: "Just think, in the course of only a few days Russia had made the transition from the most brutal and cruel arbitrary rule to the freest country in the world." (15)

In his speech Lenin attacked Bolsheviks for supporting the Provisional Government. Instead, he argued, revolutionaries should be telling the people of Russia that they should take over the control of the country. In his speech, Lenin urged the peasants to take the land from the rich landlords and the industrial workers to seize the factories. Lenin accused those Bolsheviks who were still supporting the government of Prince Georgi Lvov of betraying socialism and suggested that they should leave the party. Lenin ended his speech by telling the assembled crowd that they must "fight for the social revolution, fight to the end, till the complete victory of the proletariat". (16)

Some of the revolutionaries in the crowd rejected Lenin's ideas. Alexander Bogdanov called out that his speech was the "delusion of a lunatic." Joseph Goldenberg, a former of the Bolshevik Central Committee, denounced the views expressed by Lenin: "Everything we have just heard is a complete repudiation of the entire Social Democratic doctrine, of the whole theory of scientific Marxism. We have just heard a clear and unequivocal declaration for anarchism. Its herald, the heir of Bakunin, is Lenin. Lenin the Marxist, Lenin the leader of our fighting Social Democratic Party, is no more. A new Lenin is born, Lenin the anarchist." (17)

Joseph Stalin was in a difficult position. As one of the editors of Pravda, he was aware that he was being held partly responsible for what Lenin had described as "betraying socialism". Stalin had two main options open to him: he could oppose Lenin and challenge him for the leadership of the party, or he could change his mind about supporting the Provisional Government and remain loyal to Lenin. After ten days of silence, Stalin made his move. In the newspaper he wrote an article dismissing the idea of working with the Provisional Government. He condemned Alexander Kerensky and Victor Chernov as counter-revolutionaries, and urged the peasants to takeover the land for themselves. (18)

Alexander Kerensky

Soon after taking power Pavel Milyukov, the foreign minister, wrote to all Allied ambassadors describing the situation since the removal of the Tsar: "Free Russia does not aim at the domination of other nations, or at occupying by force foreign territories. Its aim is not to subjugate or humiliate anyone. In referring to the "penalties and guarantees" essential to a durable peace the Provisional Government had in view reduction of armaments, the establishment of international tribunals, etc." He attempted to maintain the Russian war effort but he was severely undermined by the formation of soldiers' committee that demanded "peace without annexations or indemnities". (19)

As Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) pointed out: "On the 20th April, Milyukov's note was made public, to the accompaniment of intense popular indignation. One of the Petrograd regiments, stirred up by the speeches of a mathematician who happened to be serving in the ranks, marched to the Marinsky Palace (the seat of the government at the time) to demand Milyukov's resignation." With the encouragement of the Bolsheviks, the crowds marched under the banner, "Down with the Provisional Government". (20)

Ariadna Tyrkova, a member of the Cadets, argued: "A man of rare erudition and of an enormous power for work, Milyukov had numerous adherents and friends, but also not a few enemies. He was considered by many as a doctrinaire on account of the stubbornness of his political views, while his endeavours to effect a compromise for the sake of rallying larger circles to the opposition were blamed as opportunism. As a matter of fact almost identical accusations were showered upon him both from Right and Left. This may partly be explained by the fact that it is easier for Milyukov to grasp an idea than to deal with men, as he is not a good judge of either their psychology or their character." (21)

On 5th May, Pavel Milyukov and Alexander Guchkov, the two most conservative members of the Provisional Government, were forced to resign. Mikhail Tereshchenko replaced Milyukov as Foreign Minister and Alexander Kerensky moved from Justice to the War Ministry, while five Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries from the Petrograd Soviet stepped into the cabinet to share the problems of the administration. This included Victor Chernov (Agriculture) and Irakli Tsereteli (Posts and Telegraphs). (22)

Kerensky appointed General Alexei Brusilov as the Commander in Chief of the Russian Army. He toured the Eastern Front where he made a series of emotional speeches where he appealed to the troops to continue fighting. On 18th June, Kerensky announced a new war offensive. According to David Shub: "The main purpose of the drive was to force the Germans to return to the Russian front the divisions which they had diverted to France in preparation for an all-out offensive against the Western Allies. At the same time, the Provisional Government hoped this move would restore the fighting spirit of the Russian Army." (23)

Encouraged by the Bolsheviks, who favoured peace negotiations, there were demonstrations against Kerensky in Petrograd. The Bolshevik popular slogan "Peace, Bread and Land", helped to increase support for the revolutionaries. By the summer of 1917, the membership of the Bolshevik Party had grown to 240,000. The Bolsheviks were especially favoured by the soldiers who found Lenin's promise of peace with Germany extremely attractive. (24)

Prince George Lvov was in conflict with Victor Chernov over the changes taking place over land ownership. Chernov issued circulars that supported the actions of the local land committees in reducing the rents of land leased by the peasants, seizing untilled fields for peasant use and commanding prisoner-of-war labour from private landowners. Lvov accused Chernov of going the back of the government and he prevailed on the ministry of justice to challenge the legality of Chernov's circulars. Without the full support of the cabinet in this dispute, Lvov resigned as prime minister on 7th July. (25)

The Kornilov Revolt

Alexander Kerensky became the new prime minister and soon after taking office, he announced another new offensive. Soldiers on the Eastern Front were dismayed at the news and regiments began to refuse to move to the front line. There was a rapid increase in the number of men deserting and by the autumn of 1917 an estimated 2 million men had unofficially left the army. Some of these soldiers returned to their homes and used their weapons to seize land from the nobility. Manor houses were burnt down and in some cases wealthy landowners were murdered. Kerensky and the Provisional Government issued warnings but were powerless to stop the redistribution of land in the countryside.

After the failure of the July Offensive on the Eastern Front, Kerensky replaced General Alexei Brusilov with General Lavr Kornilov, as Supreme Commander of the Russian Army. Kornilov had a fine military record and unlike most of the Russian senior officers, came "from the people" as he was the son of a poor farmer. "This combination made Kornilov the man of destiny in the eyes of those conservative and moderate politicians... who hoped that through him the Revolution might be tamed. But not only the right pinned its hopes on Kornilov. Kerensky and some in in his entourage hoped to use the general to destroy any future Bolshevik threat and to remove or diminish the tutelage of the soviets over the Provisional Government." (26)

However, the two men soon clashed about military policy. Kornilov wanted Kerensky to restore the death-penalty for soldiers and to militarize the factories. He told his aide-de-camp, that "the time had come to hang the German agents and spies, headed by Lenin, to disperse the Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies so that it can never reassemble." On 7th September, Kornilov demanded the resignation of the Cabinet and the surrender of all military and civil authority to the Commander in Chief. Kerensky responded by dismissing Kornilov from office and ordering him back to Petrograd. (27)

Kornilov now sent troops under the leadership of General Aleksandr Krymov to take control of Petrograd. Kornilov believed that he was going to become military dictator of Russia. He had the open support of a number of prominent Russian industrialists, headed by Aleksei Putilov, owner of the steelworks and the leading Petrograd banker. Others involved in the plot included Alexander Guchkov, a backer of an organization called the Union for Economic Revival of Russia. According to one source these industrialists had raised 4 million rubles for Kornilov's conspiracy. (28)

Kerensky was now in danger and so he called on the Soviets and the Red Guards to protect Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, who controlled these organizations, agreed to this request, but in a speech made by their leader, Lenin, he made clear they would be fighting against Kornilov rather than for Kerensky. Within a few days Bolsheviks had enlisted 25,000 armed recruits to defend Petrograd. While they dug trenches and fortified the city, delegations of soldiers were sent out to talk to the advancing troops. Meetings were held and Kornilov's troops decided to refuse to attack Petrograd. General Krymov committed suicide and Kornilov was arrested and taken into custody. (29)

Kerensky now became the new Supreme Commander of the Russian Army. His continued support for the war effort made him unpopular in Russia and on 8th October, Kerensky attempted to recover his left-wing support by forming a new coalition that included three Mensheviks and two Socialist Revolutionaries. However, with the Bolsheviks controlling the Soviets, and now able to call on a large armed militia, Kerensky was unable to reassert his authority.

Some members of the Constitutional Democratic Party urged Pavel Milyukov to take action against the Provisional Government. He defended his position by arguing: "It will be our task not to destroy the government, which would only aid anarchy, but to instill in it a completely different content, that is, to build a genuine constitutional order. That is why, in our struggle with the government, despite everything, we must retain a sense of proportion.... To support anarchy in the name of the struggle with the government would be to risk all the political conquests we have made since 1905." (30)

The Cadet party newspaper did not take the Bolshevik challenge seriously: "The best way to free ourselves from Bolshevism would be to entrust its leaders with the fate of the country... The first day of their final triumph would also be the first day of their quick collapse." Leon Trotsky accused Milyukov of being a supporter of General Lavr Kornilov and trying to organize a right-wing coup against the Provisional Government. Nikolai Sukhanov, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party argued that in Russia there was "a hatred for Kerenskyism, fatigue, rage and a thirst for peace, bread and land". (31)

Alexander Kerensky later claimed he was in a very difficult position and described Milyukov's supporters as being Bolsheviks of the Right: "The struggle of the revolutionary Provisional Government with the Bolsheviks of the Right and of the Left... We struggled on two fronts at the same time, and no one will ever be able to deny the undoubted connection between the Bolshevik uprising and the efforts of Reaction to overthrow the Provisional Government and drive the ship of state right onto the shore of social reaction." Kerensky argued that Milyukov was now working closely with other right-wing forces to destroy the Provisional Government: "In mid-October, all Kornilov supporters, both military and civilian, were instructed to sabotage government measures to suppress the Bolshevik uprising." (32)

Isaac Steinberg pointed out that only the Bolsheviks were showing determined leadership. "The army, exhausted by a desperate thirst for peace and anticipating all the horrors of a new winter campaign, was looking for a decisive change in policy. The peasantry, yearning for freed land and fearing to lose it in incomprehensive delays, was also waiting for this change. The proletariat, having seen lock-outs, unemployment and the collapse of industry and dreaming of a new social order, which must be born of the revolutionary storm, of which it was the vanguard, awaited this change." (33)

John Reed was a journalist who was living in Petrograd at the time: "Week by week food became scarcer. The daily allowance of bread fell from a pound and a half to a pound, than three-quarters, half, and a quarter-pound. Towards the end there was a week without any bread at all. Sugar one was entitled to at the rate of two pounds a month - if one could get it at all, which was seldom. A bar of chocolate or a pound of tasteless candy cost anywhere from seven to ten roubles - at least a dollar. For milk and bread and sugar and tobacco one had to stand in queue. Coming home from an all-night meeting I have seen the tail beginning to form before dawn, mostly women, some babies in their arms." (34)

It has been argued that Lenin was the master of good timing: "Rarely had he (Lenin) displayed to better advantage his sense of timing, his ability to see one jump ahead of his opponents. He had spurred his men on in April, May and June; he held them back in July and August; now, after the Kornilov fiasco, he once again spurred them on." (35) He began writing The State and Revolution, where he called upon the Bolsheviks to destroy the old state machinery for the purpose of overthrowing the bourgeoisie, destroying bourgeois parliamentarism... for the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat." (36)

The Bolshevik Revolution

Lenin now decided it was time to act. On 20th October, the Military Revolutionary Committee had its first meeting. Members included Joseph Stalin, Andrey Bubnov, Moisei Uritsky, Felix Dzerzhinsky and Yakov Sverdlov. According to Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967): "Despite Menshevik charges of an insurrectionary plot, the Bolsheviks were still vague about the role this organisation might play... Several days were to pass before the committee became an active force. Nevertheless, here was the conception, if not the actual birth, of the body which was to superintend the overthrow of the Provisional Government." (137)

On 24th October, 1917, Lenin wrote a letter to the members of the Central Committee: "The situation is utterly critical. It is clearer than clear that now, already, putting off the insurrection is equivalent to its death. With all my strength I wish to convince my comrades that now everything is hanging by a hair, that on the agenda now are questions that are decided not by conferences, not by congresses (not even congresses of soviets), but exclusively by populations, by the mass, by the struggle of armed masses… No matter what may happen, this very evening, this very night, the government must be arrested, the junior officers guarding them must be disarmed, and so on… History will not forgive revolutionaries for delay, when they can win today (and probably will win today), but risk losing a great deal tomorrow, risk losing everything." (38)

Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev opposed this strategy. They argued that the Bolsheviks did not have the support of the majority of people in Russia or of the international proletariat and should wait for the elections of the proposed Constituent Assembly "where we will be such a strong opposition party that in a country of universal suffrage our opponents will be compelled to make concessions to us at every step, or we will form, together with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, non-party peasants, etc., a ruling bloc which will fundamentally have to carry out our programme." (39)

Leon Trotsky supported Lenin's view and urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The Smolny Institute became the headquarters of the revolution and was transformed into a fortress. Trotsky reported that the "chief of the machine-gun company came to tell me that his men were all on the side of the Bolsheviks". (40)

The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. The Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace. (41)

Bessie Beatty, an American journalist, entered the Winter Palace with the Red Guards: "At the head of the winding staircase groups of frightened women were gathered, searching the marble lobby below with troubled eyes. Nobody seemed to know what had happened. The Battalion of Death had walked out in the night, without firing so much as a single shot. Each floor was crowded with soldiers and Red Guards, who went from room to room, searching for arms, and arresting officers suspected of anti-Bolshevik sympathies. The landings were guarded by sentries, and the lobby was swarming with men in faded uniforms. Two husky, bearded peasant soldiers were stationed behind the counter, and one in the cashier's office kept watch over the safe. Two machine-guns poked their ominous muzzles through the entryway." (42)

Louise Bryant, another journalist commented that there were about 200 women soldiers in the palace and they were "disarmed and told to go home and put on female attire". She added: "Every one leaving the palace was searched, no matter on what side he was. There were priceless treasures all about and it was a great temptation to pick up souvenirs. I have always been glad that I was present that night because so many stories have come out about the looting. It was so natural that there should have been looting and so commendable that there was none." (43)

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Victor Nogin (Trade and Industry), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice), Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War), Nikolai Krylenko (War Affairs), Pavlo Dybenko (Navy Affairs), Ivan Skvortsov-Stepanov (Finance), Vladimir Milyutin (Agriculture), Ivan Teodorovich (Food), Georgy Oppokov (Justice) and Nikolai Glebov-Avilov (Posts & Telegraphs). (44)

As chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Lenin made his first announcement of the changes that were about to take place. Banks were nationalized and workers control of factory production was introduced. The most important reform concerned the land: "All private ownership of land is abolished immediately without compensation... Any damage whatever done to the confiscated property which from now on belongs to the whole People, is regarded as a serious crime, punishable by the revolutionary tribunals." (45)

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Bruce Lockhart, report sent to the British government (27th March, 1917)

So far the people of Moscow have behaved with exemplary restraint. For the moment, only enthusiasm prevails, and the struggle which is almost bound to ensure between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat has not yet made its bitterness felt.

The Socialist Party is at present divided into two groups: the Social Democrats and Soviet Revolutionaries. The activities of the first named are employed almost entirely among the work people, while the Social Revolutionaries work mainly among the peasantry.

The Social Democrats, who are the largest party, are, however, divided into two groups known as the Bolsheviki and the Mensheviki. The bolsheviki are the more extreme party. They are at heart anti-war. In Moscow at any rate the Mensheviki represent today the majority and are more favourable to the war.

(2) Harold Williams, Daily Chronicle (17th March, 1917)

The composition of the new government is extraordinarily moderate in the circumstances. There has been, and still is, danger from extremists, who want at once to turn Russia into a Socialist republic and have been agitating amongst soldiers, but reason has been reinforced by a sense of danger from the Germans and the lingering forces of reaction gaining the upper hand.

In numberless talks I have had with soldiers I have been struck by their fundamental reasonableness, their sense of order and discipline. They wish to be free men, but very strongly realize their duty as soldiers. The more moderate Socialists, the so-called Plekhanov party, who stand for war, are very useful as mediators, and as soon as the new Government secures its ground the influence of the extremists will be diminished.

(3) John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World (1919)

The policy of the Provisional Government alternated between ineffective reforms and stern repressive measures. An edict from the Socialist Minister of Labour ordered all the Workers' Committees henceforth to meet only after working hours. Among the troops at the front, 'agitators' of opposition political parties were arrested, radical newspapers closed down, and capital punishment applied - to revolutionary propagandists. Attempts were made to disarm the Red Guard. Cossacks were spent order in the provinces.

In September 1917, matters reached a crisis. Against the overwhelming sentiment of the country, Kerensky and the 'moderate' Socialists succeeded in establishing a Government of Coalition with the propertied classes; and as a result, the Mensheviki and Socialist Revolutionaries lost the confidence of the people for ever.

Week by week food became scarcer. The daily allowance of bread fell from a pound and a half to a pound, than three-quarters, half, and a quarter-pound. Towards the end there was a week without any bread at all. Sugar one was entitled to at the rate of two pounds a month - if one could get it at all, which was seldom. A bar of chocolate or a pound of tasteless candy cost anywhere from seven to ten roubles - at least a dollar. For milk and bread and sugar and tobacco one had to stand in queue. Coming home from an all-night meeting I have seen the tail beginning to form before dawn, mostly women, some babies in their arms.

(4) Statement issued by the Petrograd Soviet (9th April, 1917)

We are appealing to our brother proletarians of the Austro-German coalition. The Russian Revolution will not retreat before the bayonets of conquerors and will not allow itself to be crushed by military force. But we are calling to you, throw off your yoke of your semi-autocratic rule as the Russian people have shaken off the Tsar's and then by our united efforts we will stop the horrible butchery which is disgracing humanity and is beclouding the great days of the birth of Russian freedom. Proletarians of all countries unite.

(5) Maxim Gorky, letter to his son (April, 1917)

Remember, the revolution just began, it will last for a long time. We won not because we are strong, but because the government was weak. We have made a political revolution and have to reinforce our conquest. I am a social democrat, but I am saying and will continue to say, that the time has not come for socialist-style reforms. The new government has inherited not a state but its ruins.

(6) Pavel Milyukov, Foreign Minister of the Provisional Government, letter sent to all Allied ambassadors (18th April, 1917)

Free Russia does not aim at the domination of other nations, or at occupying by force foreign territories. Its aim is not to subjugate or humiliate anyone. In referring to the "penalties and guarantees" essential to a durable peace the Provisional Government had in view reduction of armaments, the establishment of international tribunals, etc.

(7) Harold Williams, Daily Chronicle (22nd March, 1917)

Kerensky is a young man in his early thirties, of medium height, with a slight stoop, and a quick, alert movement, with brownish hair brushed straight up, a broad forehead already lined, a sharp nose, and bright, keen eyes, with a certain puffiness in the lids due to want of sleep, and a pale, nervous face tapering sharply to the chin. His whole bearing was that of a man who could control masses.

He was dressed in a grey, rather worn suit, with a pencil sticking out of his breast pocket. He greeted us with a very pleasant smile, and his manner was simplicity itself. He led us into his study, and there we talked for an hour. We discussed the situation thoroughly, and I got the impression that Kerensky was not only a convinced and enthusiastic democrat, ready to sacrifice his life if need be for democracy - that I already knew from previous acquaintance - but that he had a clear, broad perception of the difficulties and dangers of the situation, and was preparing to meet them.

(8) E. H. Wilcox was very impressed with Alexander Kerensky and praised him in his book, Russia's Ruin (1919)

Kerensky became the personification of everything that was good and noble in Russia. He was no longer the leader of the political Party, but the prophet of a new faith, the high priest of a new doctrine, which were to embrace all Russia, all mankind. Whatever he may have been before or after, during this dazzling and intoxicating interlude he had in him true elements of greatness.

(9) Robert Wilton, The Times (19th March, 1917)

I regret to have to say that some students of both sexes are blindly cooperating in this anarchistic propaganda. However, today the outlook is distinctly more hopeful and it is possible that a breach between the extremists and the moderates may be avoided, both agreeing to support the present Temporary Government until a Constituent Assembly decides the fate of Russia by the votes of all her 170 million people. The organization of this gigantic general election will naturally take time.

(10) General Peter Wrangel went to St. Petersburg after the February Revolution and the creation of the Provisional Government.

The first thing I noticed in Petersburg was the profusion of red ribbon. Everyone was decorated with it, not only soldiers, but students, chauffeurs, cab-drivers, middle-class folk, women, children, and many officers. Men of some account, such as old generals and former aides-de-camp to the Tsar, wore it too.

I expressed my astonishment to an old comrade of mine at seeing him thus adorned. He tried to laugh it off, and said jokingly: "Why, my dear fellow, don't you know that it's the latest fashion?"

I considered this ridiculous adornment absolutely useless. Throughout my stay in the capital I wore the Tsarevich's badge, the distinguishing mark of my old regiment, on my epaulettes, and, of course, I wore no red rag.

(11) Albert Rhys Williams described the arrival of troops to put down the Bolshevik uprising in July, 1917, in his book, Through the Russian Revolution.

On the third day the troops arrive. Bicycle battalions, the reserve regiments, and then the long grim lines of horsemen, the sun glancing on the tips of their lances. They are the Cossacks, ancient foes of the revolutionists, bring dread to the workers and the joy to the bourgeoisie. The avenues are filled now with well-dressed throngs cheering the Cossacks, crying "Shoot the rabble". "String up the Bolsheviks".

A wave of reaction runs through the city. Insurgent regiments are disarmed. The death penalty is restored. The Bolshevik papers are suppressed. Forged documents attesting the Bolsheviks as German agents are handled to the press. Leaders like Trotsky and Kollontai are thrown into prison. Lenin and Zinoviev are driven into hiding. In all quarters sudden seizures, assaults and murder of workingmen.

(12) In his book, My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution (1969), Morgan Philips Price described the demonstrations that took place in Russia on 1st May, 1917.

I do not think I ever saw a more impressive spectacle than on this occasion. It was not merely a labour demonstration, although every socialist party and workmen's union in Russia was represented there, from anarcho-syndicalists to the most moderate of the middle-class democrats. It was not merely an international demonstration, although every nationality of what had been the Russian Empire was represented there with its flag and inscription in some rare, strange tongue, from the Baltic Finns to the Tunguses of Siberia. The First of May celebration, 1917, in Petrograd and throughout the length and breadth of Russia was really a great religious festival, in which the whole human race was invited to commemorate the brotherhood of man. Revolutionary Russia had a message to the world, and was telling it across the roar of the cannons and the din of battle.

(13) Edward T. Heald, letter to his wife (2nd May, 1917)

The sudden burst of radical propaganda, which has developed during the past week, is attributed to a man named Lenin who has just arrived from Switzerland. He came through Germany, and rumour is that he was banqueted by Emperor Wilhelm. As he entered the country through Finland, he harangued the soldiers and workingmen along the way with the most revolutionary propaganda. One of the Americans who came through on the same train told us how disheartening it was. Lenin's first words when he got off the train at Petrograd were "Hail to the Civil war." God knows what a task the Provisional Government has on hand without adding the trouble that such a firebrand can create.

(14) Arthur Ransome was in Russia during the October Revolution.

Before the end of August it was obvious that there would be a Bolshevik majority in the Soviets that would be reflected in the composition of the Executive Committee. During the 'July Days' the weakness of the Government had been manifest. Kerensky had been weakened by the double failure, military and diplomatic, disasters in Galicia and failure to bring the warring powers together in conference at Stockholm. Both these failures had brought new strength to the Bolsheviks, and a swing to the left was inevitable.

(15) Alfred Knox believed that Alexander Kerensky was a vital member of the Provisional Government.

There is only one man who can save the country, and that is Kerensky, for this little half-Jew lawyer has still the confidence of the over-articulate Petrograd mob, who, being armed, are masters of the situation. The remaining members of the Government may represent the people of Russia outside the Petrograd mob, but the people of Russia, being unarmed and inarticulate, do not count. The Provisional Government could not exist in Petrograd if it were not for Kerensky.

(16) Morgan Philips Price, My Three Revolutions (1969)

The fall of Miliukov caused Prince Lvov to reconstruct the Provisional Government. A coalition government was formed of moderate Socialists from the Soviet and seven Liberals. The Socialists were Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. The Liberals were from the Cadets and other groups. Kerensky became War Minister. He was a lawyer who made a great name for himself in defending victims of Tsarist oppression and was generally very popular. The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries believed that at that stage of the Revolution the workers and soldiers of the Army were unable to run the country alone and needed the co-operation of the middle-class Liberals.

(17) Alfred Knox, diary entry (20th July, 1917)

Events have moved with dramatic quickness. Kerensky returned from the front last night and, in a stormy meeting of the Ministry, demanded dictatorial powers in order to bring the army back to discipline. The socialists disagreed. Lvov and Tereshchenko did their utmost to reconcile the diverging views. While addressing the men he was handed a telegram telling him of the disaster on the South-West Front, where the Germans have broken through. He took back the telegram to the Ministerial Council and the attitude changed. Lvov has resigned and Kerensky will be Prime Minister and Minister of War.

(18) In her book The Red Heart of Russia (1919), Bessie Beatty described how the Russian people left their factories in order to defend the Bolshevik Revolution from the threatened attack by troops led by Alexander Kerensky.

The factory gates opened wide, and the amazing army of the Red Guard, ununiformed, untrained, and certainly unequipped for battle with the traditional backbone of the Russian military, marched away to defend the revolutionary capital and the victory of the proletariat. Women walked by the side of men, and small boys tagged along on the fringes of the procession. Some of the factory girls wore red crosses upon the sleeves of their thin jackets, and packed a meague kitbag of bandages and first-aid accessories. Most of them carried shovels with which to did trenches.

(19) Robert V. Daniels, Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967)

Monday September 25 saw a crystallization of leadership on both sides, government and revolutionary. Kerensky was finally able to announce the formation of a new provisional cabinet, more than half new men, largely from the Kadets and other moderate groups, plus three Mensheviks and two SRs. The same day the Petrograd Soviet resumed business, now that its leaders were no longer involved in the Democratic Conference, and finally elected a new Executive Committee to replace the body that had resigned September 9. The results, reflecting six months of revolutionary upsurge, were as follows: Workers' Section -Bolsheviks, 13; SRs, 6; Mensheviks, 3; Soldiers' Section-Bolsheviks, 9; SRs, 10; Mensheviks, 3. Bolsheviks held exactly half the total, and with the support of the left-wingers among the SRs, had a good working majority. The first step of the new majority was to install Trotsky as chairman of the soviet. (A week or two later the Soldiers' Section elected as its leader Andrei Sadovsky, an activist of the Bolshevik Military Organization.) Predictably the soviet passed a resolution offered by Trotsky condemning the counterrevolutionary nature of Kerensky's new coalition cabinet, and calling on the masses to struggle through the soviets for revolutionary power.

(20) Alexander Kerensky, order issued on 24th October, 1917.

I order all military units and detachments to remain in their barracks until further orders from the Staff of the Military District. All officers who act without orders from their superiors will be court-martialed for mutiny. I forbid absolutely any execution by soldiers of instructions from other organizations.

(21) During the summer of 1917 George Buchanan became concerned about the survival of the Provisional Government.

The Russian idea of liberty is to take things easily, to claim double wages, to demonstrate in the streets, and to waste time in talking and in passing resolutions at public meetings. Ministers are working themselves to death, and have the best intentions; but, though I am always being told that their position is becoming stronger, I see no signs of their asserting their authority. The Soviet continues to act as if it were the Government.

The military outlook is most discouraging. Nor do I take an optimistic view of the immediate future of the country. Russia is not ripe for a purely democratic form of government, and for the next few years we shall probably see a series of revolutions or counter-revolutions. A vast Empire like this, with all its different races, will not long hold together under a Republic. Disintegration will, in my opinion, sooner or later set in, even under a federal system.

(22) Alexander Kerensky, speech made at the Council of the Republic ( 24th October, 1917)

I will cite here the most characteristic passage from a whole series of articles published in Rabochi Put by Lenin, a state criminal who is in hiding and whom we are trying to find. This state criminal has invited the proletariat and the Petrograd garrison to repeat the experience of 16-18 July, and insists upon the immediate necessity for an armed rising. Moreover, other Bolshevik leaders have taken the floor in a series of meetings, and also made an appeal to immediate insurrection. Particularly should be noticed the activity of the present president of the Petrograd Soviet, Trotsky.

The policy of the Bolsheviki is demagogic and criminal, in their exploitation of the popular discontent. But there is a whole series of popular demands which have received no satisfaction up to now. The question of peace, land, and the democratization of the army ought to be stated in such a fashion that no soldier, peasant, or worker would have the least doubt that our Government is attempting, firmly and infallibly, to solve them.

The Provisional Government has never violated the liberty of all citizens of the State to use their political rights. But now the Provisional Government declares, in this moment those elements of the Russian nation, those groups and parties who have dared to lift their hands against the free will of the Russian people, at the same time threatening to open the front to Germany, must be liquidated.

(23) Nikolai Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution of 1917 (1922)

Antonov-Ovseenko's plan was accepted. It consisted in occupying first of all those parts of the city adjoining the Finland Station: the Vyborg Side, the outskirts of the Petersburg Side, etc. Together with the units arriving from Finland it would then be possible to launch an offensive against the centre of the capital.

Beginning at 2 in the morning the stations, bridges, lighting installations, telegraphs, and telegraphic agency were gradually occupied by small forces brought from the barracks. The little groups of cadets could not resist and didn't think of it. In general the military operations in the politically important centres of the city rather resembled a changing of the guard. The weaker defence force, of cadets retired; and a strengthened defence force, of Red Guards, took its place.

(24) Pavel Manlyantovich was Minister of Justice in the Provisional Government. He was arrested by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko and the Red Guards on 25th October, 1917. He later wrote about the incident in his book, In the Winter Palace (1918)

There was a noise behind the door and it burst open like a splinter of wood thrown out by a wave, a little man flew into the room, pushed in by the onrushing crowd which poured in after him, like water, at once spilled into every corner and filled the room.

"Where are the members of the Provisional Government?"

"The Provisional Government is here," said Kornovalov, remaining seated."What do you want?"

"I inform you, all of you, members of the Provisional Government, that you are under arrest. I am Antonov-Ovseenko, chairman of the Military Revolutionary Committee."

"Run them through, the sons of bitches! Why waste time with them? They've drunk enough of our blood!" yelled a short sailor, stamping the floor with his rifle."

There were sympathetic replies: "What the devil, comrades! Stick them all on bayonets, make short work of them!"

Antonov-Ovseenko raised his head and shouted sharply: "Comrades, keep calm!" All members of the Provisional Government are arrested. They will be imprisoned in the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul. I'll permit no violence. Conduct yourself calmly. Maintain order! Power is now in your hands. You must maintain order!"

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II (Answer Commentary)

The Provisional Government (Answer Commentary)

The Kornilov Revolt (Answer Commentary)

The Bolsheviks (Answer Commentary)

The Bolshevik Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject