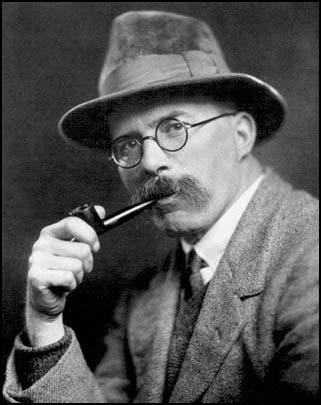

Arthur Ransome

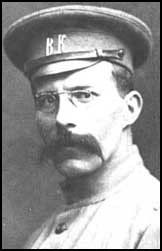

Arthur Ransome, the son of Cyril Ransome and Edith Boulton, was born at 6 Ash Grove, Headingley, Leeds on 18th January, 1884. His parents had held strong liberal views in their youth. Cyril wrote to Edith just before they got married: "I like you to be independent and think for yourself. I know among weak conventional people it is assumed that wives think just like their husbands and it is thought so nice and so pretty, while I think it is simply degrading to one and demoralizing to the other."

However, Cyril Ransome, who was professor of history at Yorkshire College (later to become Leeds University), was a committed conservative by the time Arthur was born. Arthur was introduced to radical beliefs by his neighbour, Isabella Ford, a leading figure in the Independent Labour Party and a pioneer of women's trade unions. It was at her home that Arthur met Prince Peter Kropotkin.

Arthur Ransome had a difficult relationship with his father. Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009) has pointed out: "Professor Ransome had tried to teach his eldest son to swim by throwing him over the side of a boat, and had the pleasure of watching him sink like a stone... Ransome acknowledged that his father was motivated only by the best of intentions, but revealed in one anecdote after another how his early development was impeded by an imagination so much less joyful and fertile than his own that rebellion was all but inevitable. Following the disastrous swimming lesson, he had taken himself, using his own pocket money, to the Leeds public baths, where he taught himself the backstroke in secret, only to be told when announcing the fact at breakfast that he was a liar. When the feat was eventually proved in situ, his father relented, but Ransome never truly forgave the accusation. He liked to remember the incident whenever any aspersion was cast on his honesty."

Early Journalism

Ransome was educated by private tutors before being sent to the Old College at Windermere. He disliked boarding school and did not do well in his studies. When he was ten his father broke his ankle. Arthur explained in his autobiography: "For a long time he walked with crutches, the foot monstrously bandaged. The doctors were slow in finding what had happened, probably because my father was so sure himself. In the end they found that he had damaged a bone and that some form of tuberculosis had attacked the damaged place. His foot was cut off. Things grew no better and his leg was cut off at the knee. Even that was not enough and it was cut off at the thigh."

Cyril Ransome intended to stand as the Conservative Party candidate for Rugby but he died in 1897 just before Arthur was due to start at Rugby School: "I walked alone behind my father's coffin which, carried by six of his friends of unequal height, lurched horribly on its way. As the earth rattled on the lid of the coffin I stood horrified at myself, knowing that with my real sorrow, because I had liked and admired my father, was mixed a feeling of relief. This did not last. After the funeral more than one of my father's friends thought it well to remind me that I was now the head of the family with a heavy responsibility towards my mother and the younger ones. And my mother, feeling that she had to fill my father's place and determined to carry out his wishes now as when he was alive, told me (though I knew only too well already) of my father's fears for my character and her hopes that from now on I would remember to set a good example to my brothers and sisters." Ransome later wrote: "I have been learning ever since how much I lost in him. He had been disappointed in me, but I have often thought what friends we could have been had he not died so young."

Ransome friends at Rugby included Morgan Philips Price, Richard H. Tawney, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Harry Ricardo and Edward Taylor Scott, the son of C.P. Scott. Ransome continued to underachieve at school but did develop a good relationship with his English teacher, W. H. D. Rouse: "My greatest piece of good fortune in coming to Rugby was that... I came at once into the hands of a most remarkable man whom I might otherwise never have met. This was Dr W.H.D. Rouse... He saw nothing wrong in my determination some day to write books for myself, and to the dismay of my mother did everything he could to help me."

Publishing

At the age of seventeen Ransome was offered a job with Grant Richards, a twenty-nine year old publisher. His first cousin, Laurence Binyon, a promising poet, gave him a good reference. Edith Ransome met Richards and agreed that her son should work for the young publisher: "She called on Mr Richards and was charmed by him. His offer was accepted, and within a year of leaving Rugby, I had become a London office boy with a salary of eight shillings a week."

According to Roland Chambers, his biographer, "Ransome handled every sort of menial task: wrapping books, fetching staff lunches from the local public houses, filling in labels, checking invoices and saving on postage by delivering parcels on foot. Before he had been in London more than a few weeks he knew every bookshop in and around Soho... Since Richards's business was overstretched and understaffed, he was soon given more responsible work: calling in sample bindings, ordering paper, learning the bibliographic language so essential to his trade. But Ransome was not content to remain at the manufacturing and distributive end of the industry. He wanted to be a writer." Ransome moved to the Unicorn Press and worked closely with the writers Edward Thomas, John Masefield, Lascelles Abercrombie and Yone Noguchi. Another friend, Cecil Chesterton, was a convinced socialist and the two men attended meetings of the Fabian Society.

Ransome became friendly with William G. Collingwood, the author and artist and for many years a close associate of John Ruskin. Ransome spent time with two of Collingwood's daughters, Dora, Barbara and Ursula. On 3rd June 1904, Dora wrote in her diary: "Last Saturday Mr Ransome came to dinner. He is staying in the village and has been to dinner every day since. Today he has been on the water with us from 9 to 7 with an interval for lunch. This evening we stayed in the garden and he tried to make us see fairies."

Over the next few years Ransome "scratched a living" by writing stories and articles. His literary masters were William Morris, Thomas Carlyle and William Hazlitt. Morris and other Christian Socialists were especially important to him: "I read entranced of the lives of William Morris and his friends, of lives in which nothing seemed to matter except the making of lovely things and the making of a world to match them... From that moment I suppose, my fate was decided, and any chance I had ever had of a smooth career in academic or applied science was gone forever."

Ransome accepted several commissions from Henry J. Drane, the publisher of "Drane's ABC Handbooks". Priced at one shilling, Ransome contributed the ABC of Physical Culture. It included seven chapters "Exercises for General Health", "Muscular", "Breathing", "Smoking", "Food", "Drinking" and "Sleep". Other titles by Ransome included Highways and Byways in Fairyland, The Child's Book of the Seasons, Pond and Stream and Bohemia in London. Ransome was also commissioned to write a series of critical anthologies, The World Story Tellers, that would include his favourite authors.

Marriage to Ivy Walker

Ransome hoped to marry Barbara Collingwood, but she turned him down. Next came her sister Dora, with equally painful results. Stephana Stevens also rejected him. According to Roland Chambers: "By 1908, virtually every woman of Ransome's acquaintance had either laughed or sighed as he protested his devotion. Some were gratifying flustered; others offered him tea. No serious offence was taken. But it was inevitable that at some point or another somebody would take him seriously, and when it happened, no one was more astonished than Ransome himself."

In early 1909 Ransome met Ivy Constance Walker in the flat rented by his friend, Ralph Courtney. Ransome later recalled: "She announced at once that she was not a barmaid, alluding, I suppose, to the impropriety of coming with young men to a young man's rooms... She had an extraordinary power of surrounding the simplest act with an air of conspiratorial secrecy and excitement." Ransome said he had fallen in love, "not happily, as with Barbara Collingwood, but in a horribly puzzled manner". Ivy told him that her mother was an unstable lunatic and her father was a sadist: "From all this fantastic horror I was to rescue her and I could see no other way before me." They married on 13th March 1909. A daughter, Tabitha, was born in 1910.

It was not a happy marriage and it did not help his writing career. Ransome wrote on 12th December, 1912: "This last year has been the worst of my life... I have not been able to work. I have allowed myself to keep my wife's times rather than my own. I have found it increasingly difficult to filch or force time for study of any kind. I have risen late, too late for a morning's work... In the evening, for fear of hearing my wife's complaint that I have been away from her all day and might at least spare her the evening, I have played cards (with her).... an ill conscience has made me ill-tempered and my wife unhappy. I have been unhappy almost always myself." Ransome's biographer, Roland Chambers, claimed his wife "shocked his Victorian sensibilities with her tantrums, her lewdness, and her longing for notoriety."

Oscar Wilde Court Case

The publisher Martin Secker commissioned Ransome to write a book on Oscar Wilde. He was given considerable help by Wilde's literary executor, Robert Ross. He provided access not only to Wilde's literary estate, but also to his own private correspondence. Ross wanted Ransome's book to help rehabilitate Wilde's reputation. Ross also wanted to gain revenge on Lord Alfred Douglas, who he considered had destroyed Wilde. He did this by letting Ransome see the unabridged copy of De Profundis, the letter Wilde wrote to Douglas when he was in Reading Prison. Ransome became only the fourth person to read the letter where Wilde accused Douglas of vanity, treachery and cowardice.

The book, Wilde: A Critical Study, was published on 12th February 1912. The following month, on 9th March, Lord Douglas filed an action for libel against Ransome and Secker. Ransome's friends, Edward Thomas, John Masefield, Lascelles Abercrombie and Cecil Chesterton gave him support and Robin Collingwood offered to pay his legal costs. Secker settled out of court and sold the copyright of the book to Methuen.

(If you are enjoying this article, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter and Google+ or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

The case against Ransome began in the High Court on 17th April 1913. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): "Douglas had a strong case. Answering the charge that his client had ruined Wilde, the prosecution pointed out that Douglas was little more than a boy when Wilde first met him, whereas Wilde, almost twenty years his senior, had already written The Picture of Dorian Grey, a scandalous work sprung from a corner of life no proper gentleman ever visited, still less boasted of in print. If there had been any corruption, it had been Wilde's corruption of Douglas."

Douglas's counsel went on to argue that Wilde was "a shameless predator who had deprived an innocent boy not only of his inheritance, but of his chastity". Douglas admitted during cross-examination by J. H. Campbell (later Lord Chief Justice of Ireland) that he had deserted Wilde before his original conviction and had not returned to England, let alone visited his friend in prison, in over two years. He also read out correspondence that indicated that Douglas had "consorted with male prostitutes" and had taken money from Wilde, not because he needed it but because it gave him an erotic thrill. Campbell read from a letter written by Douglas: "I remember the sweetness of asking Oscar for money. It was a sweet humiliation."

The case took a dramatic turn when the De Profundis letter was read out in court. It has been described as the "most devastating character assassination in the whole of literature". According to Wilde's letter, Douglas's insatiable appetite, vanity and ingratitude were responsible for every catastrophe. Wilde finished the letter with the words: "But most of all I blame myself for the entire ethical degradation I allowed you to bring on me. The basis of character is will power, and my will became utterly subject to yours. It sounds a grotesque thing to say, but it is none the less true. It was the triumph of the smaller over the bigger nature. It was the case of that tyranny of the weak over the strong which somewhere in one of my plays I describe as being the only tyranny that lasts."

Douglas, who claimed never to have read the letter, found the contents so upsetting he left the witness box, only to be called back and reprimanded by the judge. After a three-day trial, the jury took just over two hours to return its verdict. Ransome was found not guilty of libel and the publicity the book received meant that it was now going to be a bestseller. In spite of the ruling in his favour, Ransome insisted that the offending passages be deleted from every future edition of the book.

Douglas, who claimed never to have read the letter, found the contents so upsetting he left the witness box, only to be called back and reprimanded by the judge. After a three-day trial, the jury took just over two hours to return its verdict. Ransome was found not guilty of libel and the publicity the book received meant that it was now going to be a bestseller. In spite of the ruling in his favour, Ransome insisted that the offending passages be deleted from every future edition of the book.

Visits Russia in 1914

The court case had been covered in great detail by all the national newspapers. Ransome was now in a position to exploit his new fame. He had offers from publishers to write other books of a controversial nature. He rejected these offers and instead accepted a commission to produce an English guide to St. Petersburg. This would provide the opportunity to leave his wife. He had a meeting with his solicitor, Sir George Lewis, and asked him to arrange a legal separation from his wife. During his time in Russia he learnt to speak the Russian language. The book was finished in July 1914 but never published.

Ransome met Harold Williams and his wife, Ariadna Tyrkova, in Russia in 1914. Ransome later commented: "He (Williams) opened doors for me that I might have been years in finding for myself... I owe him more than I can say." People he was introduced to included Sir George Buchanan, Bernard Pares, Paul Milyukov and Peter Struve. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): Williams had a major influence on Ransome: "A shy, generous man a few years older than himself, with a pedagogic streak and a disarming stutter. Ransome benefited from Williams's encyclopedic knowledge of Russian history, his journalistic contacts and also from a friendship with Williams's wife, Ariadna Tyrkova, the first female representative elected to the Russian parliament, or State Duma, and a passionate advocate of constitutional reform. In Williams's company Ransome discussed not only politics, but philosophy, history and literature, sought out his advice on every subject and listened in amazement as he spoke in any one of the forty-two different languages used in Russia at that time."

War Reporter

Ransome was still in Russia when the First World War started in August 1914. He wrote to a friend: "The streets are full of soldiers. And, well, I always admired the Russians, but never so much as now. You know how our soldiers go off in pomp with flags and music. I have not heard a note of music since the declaration of war. They go off quite silently here in the middle of the night, carrying their little tin kettles, and for all the world like puzzled children going off to school for the first time. And the idea in all their heads is fine. They all say the same thing. We hate fighting. But if we can stop Germany then there will be peace for ever."

Ransome now returned to London where he hoped to find a newspaper willing to employ him to report on the war. In an article published on 3rd September 1914 where he predicted that at the end of the war: "England will be more English, France more French, and in the East, Russia will be more Russian and less inclined to suppose that civilization as well as the best of everything is made in Paris, London, Vienna and Berlin."

In December 1914 Ransome returned to Petrograd. Hamilton Fyfe, a journalist employed by the Daily Mail tried unsuccessfully to persuade the newspaper to send Ransome to report the war in Poland. Another friend, Harold Williams, arranged for Ransome to work for the Daily News. His first report on the Eastern Front appeared in the newspaper on 2nd September 1915.

The British government had established the secret War Propaganda Bureau on the outbreak of the First World War. Based on an idea put forward by David Lloyd George, the plan was to promoting Britain's interests during the war. This involved recruiting Britain's leading writers to write pamphlets that supported the war effort. Writers recruited included Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett, John Masefield, Ford Madox Ford, William Archer, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Parker, G. M. Trevelyan and H. G. Wells.

One of the first pamphlets to be published was Report on Alleged German Outrages, that appeared at the beginning of 1915. This pamphlet attempted to give credence to the idea that the German Army had systematically tortured Belgian civilians. The great Dutch illustrator, Louis Raemakers, was recruited to provide the highly emotionally drawings that appeared in the pamphlet.

Bernard Pares became aware of the activities of the secret War Propaganda Bureau and suggested to Robert Bruce Lockhart, the British consul-general that a similar organization should be set up in Russia to control reporting on the Eastern Front. Lockhart set up a meeting with British journalists, including Ransome, in January 1916. After talking to Harold Williams, Lockhart submitted a proposal to the British ambassador Sir George Buchanan. The project was approved and became known as the International News Agency (Anglo-Russian Bureau). Funded by the Foreign Office and headed by Hugh Walpole, it placed pro-British stories in Russian newspapers. As well as Ransome, Pares and Williams, other members included Hamilton Fyfe of the Daily News and Morgan Philips Price of the Manchester Guardian.

After visiting the Russian Army on the frontline Ransome reported: "Looking back now I seem to have seen nothing, but I did in fact see a great deal of that long-drawn-out front, and of the men who, ill-armed, ill-supplied, were holding it against an enemy who, even if his anxiety to fight was not greater than the Russians', was infinitely better equipped. I came back to Petrograd full of admiration for the Russian soldiers who were holding the front without enough weapons to go round. I was much better able to understand the grimness with which those of my friends who knew Russia best were looking into the future."

Provisional Government

As Nicholas was supreme command of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline support for the Tsar Nicholas II in Russia. On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges."

After the abdication of Tsar in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Prince Lvov had always held aloof from a purely political life. He belonged to no party, and as head of the Government could rise above party issues. Not till later did the four months of his premiership demonstrate the consequences of such aloofness even from that very narrow sphere of political life which in Tsarist Russia was limited to work in the Duma and party activity. Neither a clear, definite, manly programme, nor the ability for firmly and persistently realising certain political problems were to be found in Prince G. Lvov. But these weak points of his character were generally unknown."

Ransome reported in the Daily News on 16th March 1917: "It is impossible for people who have not lived here to know with what joy we write of the new Russian Government. Only those who know how things were but a week ago can understand the enthusiasm of us who have seen the miracle take place before our eyes. We knew how Russia worked for war in spite of her Government. We could not tell the truth. It is as if honesty had returned. Today newspapers have reappeared, and their tone and even form are so joyful that it is hard to recognize them. They are so different from the censor-ridden mutes and unhappy things of a week ago. Every paper seems to be executing a war-dance of joy."

On May 1st, 1917, Ransome went on the streets of Petrograd to witness the first official holiday of the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II: "In all directions as far as I can see red flags are waving above the dense crowd, which leaves just room for the constantly passing processions. On either side of the processions, long strings of men and women walk along holding hands... the whole town is hung with flags, banners and inscriptions. A characteristic emblem, an enormous red and white banner, hangs over the granite front of the German embassy, which was sacked in 1914 and has stood empty ever since. The banner is inscribed, Proletariat of all lands unite. That is the thought in the minds of the Russian workmen today. When will such a day be seen in Berlin?"

Ransome also reported on the Kornilov Revolt: "Last night I saw the cavalry regiment just arrived from the front to support the Government riding from the station. Dnsty, sunburnt, with full equipment and gas masks swinging in cases at their sides distinguishing them from the troops at the rear, they moved through the streets on little grey horses. One man with his reins loose on his horse's neck played the accordion accompanied by another who beat time on a tambourine. They brought with them into the hot, damp July' evening in Petrograd something of the old vigour of the front; something of the vivid contrast there has always been between the front and the rear. I have never felt so strongly that Petrograd was a sick city as when I read the little dusty red flags fastened on their green lances. Here were the original watchwords of revolution: Long Live the Russian Republic, Forward in the Name of Freedom, Liberty or Death.

Lola Kinel met Ransome on a train during the summer of 1917. She later recalled in her autobiography, Under Five Eagles (1937) that "Ransome was an odd-looking man walking up and down the corridor and throwing occasional surreptitious glances in our direction. He was tall, dressed in a Russian military coat, though without insignia, and a fur cap. He had long red moustaches, completely concealing his mouth, and humorous, twinkling eyes." Ransome delighted her with his broken Russian and they spent the rest of the journey playing chess.

Kinel visited Ransome at his room in Glinka Street in Petrograd. "It was the first bachelor room I had ever seen; it had a desk and typewriter in one corner, in another a bed, night table, and dresser all behind a screen; then a sort of social arrangement, consisting of an old sofa and a round table with some chairs around it in the centre. And books. They were everywhere heaped on the sofa and even on the floor. Among these books I found occasionally torn socks. I used to pick them up gingerly in my gloved hand and wrap them in a piece of newspaper... His own Bohemianism was not a pose but seemed real. He had, I remember, a thorough contempt for men who dressed well, or the least conventionally. He forgave women if they were pretty, but he preferred most Russian women, who do not pose and are simple, to English girls. For England he seemed to have a queer mixture of contempt, dislike, and love. He was clever, yet childish, very sincere and kind and romantic, and on the whole far more interesting than his books."

George Alexander Hill, a British spy, met Ransome during this period and commented on him in his autobiography, Go Spy the Land (1933): "A tall, lanky, bony individual, with a shock of sandy hair, usually unkempt, and the eyes of a small inqquisitive and rather mischievous boy. He really was a lovable personality when you came to know him." In fact, he was in poor health at the time. He blamed the shortage of fruit and vegetables in his diet. He wrote to his mother: "I can't cross a room without nearly collapsing and the day before yesterday I fainted in the street.

The Russian Revolution

Ransome was so ill that in October 1917 he left Russia. He was therefore in England when the Russian Revolution took place. Ransome wrote an article for the Daily News on 9th November. Ransome argued: "The lack of bloodshed during the Bolshevik coup d'état is due to two causes. First the comparative unanimity of the classes represented in the Soviet, and second to the fact that the large masses of the population increasingly despair of politics, and, though possibly disapproving, are willing to stand aside."

In a series of newspaper articles Ransome attempted to explain the Bolshevik government's attitude towards the First World War: "They do not want any peace which would leave Russia in the position of a sleeping partner of Germany. On the other hand, they are opposed to assisting what they regard as Imperialist war-aims on the part of ourselves. They will probably use their new position to press more insistently than their precursors for definition of Allied war-aims. If, however, we wish to force them into a more hostile attitude, and perhaps into a separate peace, we cannot do better than to follow the example of some of this morning's newspapers in loudly condemning what we do not understand."

Ransome argued that it was important to remember that Lenin and the Bolsheviks had been successful because they had removed an unpopular government: "The most important thing to be remembered in estimating the present situation in Russia is that Bolshevism' is a tendency quite independent of the personality and doctrines of the Bolshevik leaders. When during the last few months in Petrograd we observed to each other that more and more people were turning Bolshevik, we meant not that they were embracing the principles of Socialism as expounded by Lenin, but simply that they were coming nearer to active and open hostility to the Government."

The British government disapproved of Ransome's articles. John Pollock of The Morning Post had already told the government that he believed Ransome was a Bolshevik sympathizer and a strong opponent of David Lloyd George: "In the summer of 1917 I met him in Petrograd, where he was publicly abusing the British government, and in particular Mr Lloyd George, for setting up tyranny in England... In the Autumn of 1917 I heard that he was in close touch with the Bolshevik leaders." Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette (2013) has commented that he was a Bolshevik sympathizer: "There was some truth in this. Ransome sincerely hoped that the Bolshevik revolution would sweep away the many injustices of the old regime and offer a brighter future to the country's downtrodden poor."

On 3rd December, 1917, Ransome went to see Sir Robert Cecil, the Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs. Ransome recorded in his diary: "He stood in front of the fireplace, immensely tall, fantastically thin, his hawk-like head swinging forward at the end of a long arc formed by his body and legs. 'If you find, as you well may, that things have collapsed into chaos, what do you propose to do?' I told him that I should make no plans until I could see for myself what was happening, and that from London I could make no guess in all that fog of rumour where to look for the main thread of Russian history. He gave me his blessing, and made things easy for me, at least as far as Stockholm, by entrusting the diplomatic bag to me to deliver to the Legation there."

Ransome was friends with Zelda Kahan, a member of the the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Her brother-in-law, Theodore Rothstein, was a close friend of Lenin and wrote a letter of introduction for Ransome that he could show the Bolshevik government. It included the following passage: "Mr Ransome is the only correspondent who has informed the English public of events in Russia honestly."

Armed with this letter he traveled to Stockholm and met Vatslav Vorovsky, the head of the Bolshevik legation. His interview with Vorovsky appeared in the Daily News on 19th December, 1917. Vorovsky reminded Ransome: "You have lived in Russia long enough to know that Russia is not a condition to carry on a war. Russia must make peace. It is for the Allies to choose whether that peace is to be a separate or a general peace." Vorovsky pointed out that the Bolshevik government's quarrel was not with the English working class, but only with the British government, which clung so obstinately to the destruction of Germany.

Ransome described Vorovsky as being "well-educated, amiable and cosmopolitan". He warned that "continual sabotage on the part of the bourgeoisie may exasperate the mass of the people to such an extent as to carry them beyond the control of their leaders." He then handed Ransome his visa and he was able to move on to Russia. Ransome arrived in Petrograd on 25th December, 1917.

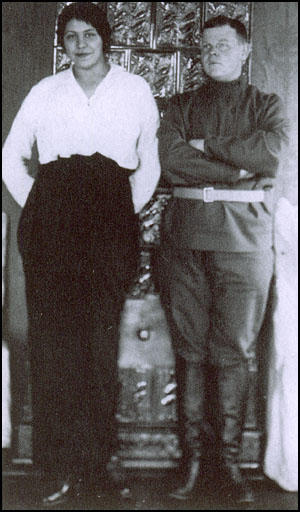

Evgenia Shelepina

Ransome first met Evgenia Shelepina when he interviewed Leon Trotsky on 28th December 1917. Shelepina was Trotsky's secretary. Ransome fell in love with Shelepina and the two became lovers. Ransome's biographer, Roland Chambers, has pointed out: "Over forty years later, Ransome remembered the decisive moment at which he realized he was in love: a mixture of terror and relief over which he had no power whatsoever. But as he snatched his future wife from beneath the wheels of history - the war, the Revolution, the fatal passage of circumstance which Lenin had declared indifferent to the fate of any single individual - the possibility of separating his private from his professional affairs remained as remote as ever."

Ransome's article on Leon Trotsky appeared in the Daily News on 31st December, 1917. "In an anteroom one of Mr Trotsky's secretaries, a young officer, told me Mr Trotsky was expecting me. Going into an inner room, unfurnished except for a writing table, two chairs and a telephone, I found the man who, in the name of the Proletariat, is practically the dictator of all Russia. He has a striking head, a very broad, high forehead above lively eyes, a fine cut nose and a small cavalier beard. Though I had heard him speak before, this was the first time I had seen him face to face. I got an impression of extreme efficiency and definite purpose. In spite of all that is said against him by his enemies, I do not think that he is a man to do anything except from a conviction that it is the best thing to be done for the revolutionary cause that is in his heart. He showed considerable knowledge of English politics."

The article quoted Trotsky as saying: "Russia is strong in that her Revolution was the starting point of a peace movement in Europe. A year ago it seemed that only militarism could end the war. It is now clear that the war will be decided by social rather than political pressure. It is to the Russian Revolution that German democracy looks, and it is the recognition of that fact that compels the German Government to accept the Russian principles as a basis for negotiation."

Ransome asked Trotsky if he considered Germany's peace offer as a joint victory of the Russian and German democracies. He replied, "Not of Russian and German democracy alone, but of the democratic movement generally. The movement is visible everywhere. Austria and Hungary are on the point of revolt, and not they alone. Every Government in Europe is feeling the pressure of democracy from below. The German attitude merely means that the German Government is wiser than most, and more realistic. It recognizes the real factors and is moved by them. The Germans have been forced by democratic pressure to throw aside their grandiose plans of conquest and to accept a peace in which there is neither conqueror nor conquered."

The article was read by the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour. He immediately telegramed the British Embassy in Petrograd and asked if Ransome could be recruited to provide his services as an unofficial agent, communicating British views to the Soviet and vive versa. Ransome agreed and reported directly to the British Ambassador, George Buchanan or Major Cudbert Thornhill of British intelligence.

Ransome's new girlfriend, Evgenia Shelepina, was a major source of secret information. Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013) commented that: "Their relationship was to transform the information he received from the regime: it was Shelepina who typed up Trotsky's correspondence and planned all his meetings. Suddenly, Ransome found himself with access to highly secretive documents and telegraphic transmissions."

Colonel Alfred Knox, the British Military Attaché at the embassy, had no idea that Ransome was working as a British agent. He was appalled by what he considered to be Ransome's pro-Bolshevik articles that were appearing in the Daily News and the New York Times. He suggested that Ransome should be "shot like a dog". Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009) argued: "Ransome's articles reflected the party line so accurately that there was little to choose between them but style, while as his relationship with Evgenia deepened, so any change of heart or sudden epiphany became that much more improbable. In his autobiography, she is pictured either as a distant functionary, handing out official releases, or as guardian of his personal happiness; never both at the same time. They had grown together gradually, as ordinary people do, strolling in the evenings, taking supper at the rooms she shared with her sister at the commissariat's headquarters in the centre of town."

Ransome developed a very intense relationship with Evgenia Shelepina and told her that as soon as he could arrange a divorce from Ivy Constance Ransome he would marry her. In his autobiography he recalled, that she had slipped when boarding a tram, and clutching the rail, was dragged full length along the track, so that if her grip had failed she would have been cut in two. "Those few horrible seconds during which she lay almost under the advancing wheel possibly determined both of our lives. But it was not until afterwards that we admitted anything of the kind to one another."

George Alexander Hill, a British diplomat in Petrograd, got to know Shelepina during this period. "She must have been two or three inches above six feet in her stockings... At first glance, one was apt to dismiss her as a very fine-looking specimen of Russian peasant womanhood, but closer acquaintance revealed in her depths of unguessed qualities.... She was methodical and intellectual, a hard worker with an enormous sense of humour. She saw things quickly and could analyse political situations with the speed and precision with which an experienced bridge player analyses a hand of cards... I do not believe she ever turned away from Trotsky anyone who was of the slightest consequence, and yet it was no easy matter to get past that maiden unless one had that something."

Bolshevik Leaders

Ransome developed a close relationship with Karl Radek, who was the Bolshevik chief of Western propaganda. Ransome argued in his autobiography: "Radek had been born in Poland and spoke Polish (badly as his wife used to say, because he had talked too much German in exile), Russian (with a remarkably Polish accent) and French with the greatest difficulty. He always talked Russian with me but loved to drag in sentences from English books, which I sometimes annoyed him by being slow to recognize.... He had an extraordinary memory and an astonishingly detailed knowledge of English politics." Ransome celebrated the Russian New Year with the Radek family and Lev Sedov, the 12 year-old son of Leon Trotsky.

In January 1918, Ransome reported on the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. "I wonder whether the English people realize how great is the matter now at stake and how near we are to witnessing a separate peace between Russia and Germany, which would be a defeat for German democracy in its own country, besides ensuring the practical enslavement of all Russia. A separate peace will be a victory, not for Germany, but for the military caste in Germany. It may mean much more than the neutrality of Russia. If we make no move it seems possible that the Germans will ask the Russians to help them in enforcing the Russian peace terms on the Allies."

Ransome feared that Russia would face anarchy if the Bolsheviks were defeated in the Constituent Assemby elections. He wrote in The Daily News: "In five days' time the Constituent Assembly meets. It now seems probable that it will contain a majority against the Bolsheviks by some other necessarily weaker government which will offer the German generals an antagonist infinitely less dangerous to them than Trotsky. Efforts are being made to secure street demonstrations in the Constituent Assembly's favour. If these efforts are successful, the result will be anarchy, for which the Germans could wish nothing better."

Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17). As David Shub pointed out, "The Russian people, in the freest election in modern history, voted for moderate socialism and against the bourgeoisie."

Lenin was bitterly disappointed with the result as he hoped it would legitimize the Russian Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was elected President. Nikolai Sukhanov argued: "Without Chernov the SR Party would not have existed, any more than the Bolshevik Party without Lenin - inasmuch as no serious political organization can take shape round an intellectual vacuum. But Chernov - unlike Lenin - only performed half the work in the SR Party. During the period of pre-Revolutionary conspiracy he was not the party organizing centre, and in the broad area of the revolution, in spite of his vast authority amongst the SRs, Chernov proved bankrupt as a political leader. Chernov never showed the slightest stability, striking power, or fighting ability - qualities vital for a political leader in a revolutionary situation. He proved inwardly feeble and outwardly unattractive, disagreeable and ridiculous."

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia.

Raymond Robins

While he was in Petrograd he met Raymond Robins, the brother of Elizabeth Robins, a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union before the war. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): "On the day after the Trotsky interview, Ransome had dined with Colonel Raymond Robins, head of the American Red Cross, and Edgar Sisson, former editor of the Chicago Tribune. Robins, he concluded, was by far the superior specimen. As an evangelical Christian, an Alaskan gold prospector and straight-talking Chicago progressive, his politics were no more compatible with Bolshevism than those of Woodrow Wilson, whom he counted amongst his personal friends. But Robins had seen the Bolsheviks at work in the regional soviets. No other government, he believed, was capable of maintaining order at home while opposing German interests. If the Allies wanted an Eastern Front, they should supply the money and arms. If they wanted peace, it would have to be a general peace. By the time Ransome returned to Petrograd, Robins was on excellent terms with Trotsky and Lenin, whom he considered men of courage and integrity." Ransome later recalled that Robins told him that Leon Trotsky was "four times son of a bitch, but the greatest Jew since Jesus."

On 25th April, 1918, Ransome had dinner with Robins. The two men agreed that the Soviet government would survive and that Western governments should not attempt to overthrow it. Ransome argued that he had written a pamphlet with Karl Radek, entitled On Behalf of Russia: An Open Letter to America. Robins, who was just about to leave for home, agreed to use his influence to get it published by The New Republic magazine.

The pamphlet was published in July 1918. It included the following passage: "These men who have made the Soviet government in Russia, if they must fail, will fail with clean shields and clean hearts, having, striven for an ideal which will live beyond them. Even if they fail, they will none the less have written a page in history more daring, than any other which I can remember in the history of humanity. They are writing it amid the slinging of mud from all the meaner spirits in their country, in yours and in my own. But when the thing is over, and their enemies have triumphed, the mud will vanish like black magic at noon, and that page will he as white as the snows of Russia, and the writing on it as bright as the gold domes I used to see glittering in the sun when I looked from my window in Petrograd."

Arthur Ransome and Lenin

Lenin was shot by Dora Kaplan, a member of the Socialist Revolutionaries, on 30th August, 1918. Two bullets entered his body and it was too dangerous to remove them. Kaplan was soon captured and in a statement she made to Cheka that night, she explained that she had attempted to kill him because he had closed down the Constituent Assembly. In a statement to the police she confessed to trying to kill Lenin. "My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot at Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution. I was exiled to Akatui for participating in an assassination attempt against a Tsarist official in Kiev. I spent 11 years at hard labour. After the Revolution, I was freed. I favoured the Constituent Assembly and am still for it."

On 2nd September, as Lenin's life hung in the balance, Ransome wrote an obituary hailing the founder of Bolshevism as "the greatest figure of the Russian Revolution". Here "for good or evil was a man who, at least for a moment, had his hand on the rudder of the world". Common peasants who had known Lenin attested to his goodness, his extraordinary generosity to children. The workers looked up to him, "not as an ordinary man, but as a saint". Without Lenin, Ransome concluded, the soviets would not perish, but they would lose their vital direction. His influence was the one constant steadying factor. He had his definite policy, and his firmness in his own position was the best curb on other, more mercurial people. In the truest sense of the word it may be said that the revolution has lost its head. Fiery Trotsky, ingenious, brilliant Radek, are alike unable to replace the cool logic of the most colossal dreamer that Russia produced in our time."

Lenin eventually recovered and the two men met several times to discuss politics. Ransome later wrote: "Not only is he without personal ambition, but, as a Marxist, believes in the movement of the masses... His faith in himself is the belief that he justly estimates the direction of elemental forces. He does not believe that one man can make or stop the revolution. If the revolution fails, it fails only temporarily, and because of forces beyond any man's control. He is consequently free, with a freedom no other great leader has ever had... He is as it were the exponent not the cause of the events that will be for ever linked with his name."

Ransome told Lenin that a Marxist revolution was unlikely to take place in Britain. Lenin replied: "We have a saying that a man may have typhoid while still on his legs. Twenty, maybe thirty years ago, I had abortive typhoid, and was going about with it, had it some days before it knocked me over. Well, England and France and Italy have caught the disease already. England may seem to you untouched, but the microbe is already there."

The Red Terror

After the assassination attempt on Lenin the authorities became more hostile to foreigners living in Russia. Ransome was warned by Karl Radek that his life would be in danger if the British government continued to give help to the White Army in the Russian Civil War. Ransome contacted his spymaster, Robert Bruce Lockhart, to help him and Evgenia Shelepina, to escape from Russia to Estonia by providing the necessary papers. Ransome promised to maintain contact with the Bolshevik leaders so he could keep the British government informed of their activities.

Lockhart agreed and sent a telegram to the Foreign Office in London in June 1918 asking for help. "A very useful lady, who has worked here in an extremely confidential position in a government office desires to give up her present position... She has been of the greatest service to me and is anxious to establish herself in Stockholm where she would be at the centre of information regarding underground agitation in Russia... In order to enable her to leave secretly, I wish to have authority to put her to Mr Ransome's passport as his wife and facilitate her departure via Murmansk." Arthur Balfour, the Foreign Secretary, arranged for the papers to be sent to Russia.

Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka, the Russian Secret Police, announced a few days later the start of the Red Terror: "We stand for organised terror, this must be clearly understood. Terror is an absolute necessity during times of revolution. Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government and the new order of life. Among such enemies are our political adversaries, as well as bandits, speculators and other criminals who undermine the foundations of the Soviet Government. To these we will show no mercy."

Bolshevik or MI6 Agent

Ransome arrived in Stockholm on 5th August, 1918. He was being monitored by MI6. A telegram arrived at the War Office on 29th August that stated: "Arthur Ransome is reported to be in Stockholm, having married Trotsky's secretary, with a large amount of Russian Government money, and to be travelling with a Bolshevik passport. The alleged marriage we understand to be a put up job and so the Bolshevik passport may be of little account, but the fact that he has a large amount of Russian Government money is of interest to us, and we would like to have him watched accordingly. Could you please wire out."

On 2nd September, 1918, Bolshevik newspapers splashed on their front pages the discovery of an Anglo-French conspiracy that involved undercover agents and diplomats. One newspaper insisted that "Anglo-French capitalists, through hired assassins, organised terrorist attempts on representatives of the Soviet." These conspirators were accused of being involved in the murder of Moisei Uritsky and the attempted assassination of Lenin. Head of Special Mission to the Soviet Government, Robert Bruce Lockhart and Sidney Reilly were both named in these reports. "Lockhart entered into personal contact with the commander of a large Lettish unit... should the plot succeed, Lockhart promised in the name of the Allies immediate restoration of a free Latvia."

An edition of Pravda declared that Lockhart was the main organiser of the plot and was labelled as "a murderer and conspirator against the Russian Soviet government". The newspaper then went on to argue: "Lockhart... was a diplomatic representative organising murder and rebellion on the territory of the country where he is representative. This bandit in dinner jacket and gloves tries to hide like a cat at large, under the shelter of international law and ethics. No, Mr Lockhart, this will not save you. The workmen and the poorer peasants of Russia are not idiots enough to defend murderers, robbers and highwaymen."

The following day Lockhart was arrested and charged with assassination, attempted murder and planning a coup d'état. All three crimes carried the death sentence. The couriers used by British agents were also arrested. Lockhart's mistress, Maria Zakrveskia, who had nothing to do with the conspiracy, was also taken into custody. Xenophon Kalamatiano, who was working for the American Secret Service, was also arrested. Hidden in his cane was a secret cipher, spy reports and a coded list of thirty-two spies. However, Sidney Reilly, George Alexander Hill, and Paul Dukes had all escaped capture and had successfully gone undercover. It is not known if Arthur Ransome had been aware of this plot to overthrow the Bolsheviks.

The start of the Red Terror changed attitudes towards Arthur Ransome in the United States. Ambassador David R. Francis reported to President Woodrow Wilson that Ransome was closely linked to Karl Radek, one of the key leaders in the Bolshevik government. Ransome's On Behalf of Russia: An Open Letter to America was attacked by the American media and it was stated that the pamphlet was being distributed to Allied troops fighting in the Russian Civil War. The New York Times denounced Ransome as being the "mouthpiece of the Bolsheviki" and announced that they would no longer be publishing his articles in their newspaper.

On 12th September, 1918, a MI6 agent in Stockholm sent a report to headquarters about Ransome: "I do not know how much is known in London of Arthur Ransome's activities here, but it certainly ought to he understood how completely he is in the hands of the Bolsheviks. He seems to have persuaded the Legation that he has changed his views to some extent but this is certainly not the case. He claims, as has already been reported to you, to be the official historian of the Bolshevik movement. I suppose this is true, at all events it is true that he is living here with a lady who was previously Trotsky's private secretary, that he spends the greater part of his time in the Bolshevik Legation, where he is provided with a typewriter, and that he is very nervous as to the effect which his present attitude and activities may have upon his prospects in England. I also know that he has informed two Russians that I, personally, am an agent of the British Government, and said that he had this information from authoritative sources, both British and Bolshevik.

Ransome then received information that Horatio Bottomley, the editor of John Bull Magazine, was threatening to expose him as a Bolshevik spy. Ransome immediately contacted his spymaster in Russia, Robert Bruce Lockhart, and told him that Bottomley intended to describe him as a "paid agent of the Bolsheviks" and asked him for help. He pointed out that he had been asked by Sir George Buchanan to be "an intermediary to ask Trotsky certain questions, my attempts to get into as close touch as possible with the Soviet people have had the full approval of the British authorities on the spot. I have never taken a single step without first getting their approval."

Ransome went onto argue that he was under orders to provide pro-Bolshevik reports: "As for my attitude towards (the Bolsheviks), please remember that you yourself suppressed a telegram I wrote on the grounds that its criticism of them would have put an end to my good relations with them and so have prevented my further usefulness. Altogether, it will be very much too much of a good thing if, after having worked as I have, and been as useful as I possibly could, I am now to be attacked in such a way that I cannot defend myself except by a highly undesirable exposition (to persons who have no right to know) of what, though not officially secret service work (because I was unpaid) amounted to the same thing." Lockhart contacted Bottomley and the article never appeared.

Defence of the Realm Act

In March 1919 Ransome arrived back in London. On 4th April he was arrested by the police under the terms of the Defence of the Realm Act. Ransome was interviewed by Sir Basil Thomson, Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. Ransome later recalled: "I was shown into Sir Basil Thomson's room and asked to sit down in the famous chair where so many criminals had sat before me." After being interviewed by Thompson he was released. Thompson told William Cavendish Bentinck that he was "satisfied that he is not a Bolshevik in the sense" that other journalists such as Morgan Philips Price.

Thompson wrote: "Ransome... thinks if something is not done soon, Russia will slip into a state of anarchy, which will be far worse than the present situation. He appears to have been very closely in touch with all the Bolshevik leaders, and is perfectly frank about what they told him. I think myself that we shall he able to restrain him from bursting into print. He wants to go into the country for six months to write a hook. All he wants to be allowed to put into print for the moment is a description of the ceremony of the International, which must have been very funny."

The following day Ransome was interviewed by Reginald Leeper, of the Political Intelligence Department. He was less convinced than Thompson about the dangers that Ransome posed: "After four hours' conversation with Ransome I believe he can do more harm in this country than even Price. Lenin would not have wasted two hours with him unless he thought he could be most useful to him here. What Lenin wants in England just now are people who will take up his policy and at the same time declare they are anti-Bolsheviks. Ransome will do this to perfection, if not by writing, then at least by talking to people."

Sir Basil Thomson, who now understood the work that Ransome had been doing for the government, over-ruled Leeper. He also gave permission for Evgenia Shelepina to enter the country. Ransome wrote to Evgenia with the news: "I have at last with great difficulty obtained permission for you to join me here in England... Do not delay for a minute... I am spending the whole time here working on my book and I am waiting for you to arrive." However, the Bolshevik government would not allow her to leave and Ransome realised he would need to go back to Russia to get her.

Adam Mars Jones has argued: "Ransome knew which side his bread was buttered on, though he may not have realised how busily it was being buttered on both sides, by British and Bolshevik agencies alike. He was nothing as complicated as a double agent, but was useful to each side only if he had some standing with the other." Sir Cavendish-Bentinck reported to the Foreign Office: "He (Ransome) is really rather a coward and is trying to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds."

Ransome and C. P. Scott

While in England he wrote Six Weeks in Russia (1919), an account of the revolution and an explanation for the signing of the Brest-Litovsk. It sold over 8,000 copies in a fortnight. It was generally well-received and only The Times Literary Supplement offered any criticism. It accepted that Ransome "had been rigorous in seeking out both Bolsheviks and their socialist opponents, had not posed a single question or queried a single answer in a way that deviated from the official Soviet line."

One man who really liked the book was C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian. He offered him £1,000 a year, excluding travel expenses, to work for his newspaper, as its correspondent in Russia. Ransome immediate accepted the offer and told Scott that because of his Bolshevik contacts would be of help to British citizens in the country: "Except under a Trotsky regime I think I could probably be of use to British subjects in Russia, should any of them get into difficulties or want to get out."

Scott now applied to the Foreign Office for permission to send Ransome to Russia. However, he had made some powerful enemies in authority who did not know he had been working for MI6. However, Colonel Norman Thwaites of the War Office who had good connections to the intelligence community wrote: "Mr. Ransome is a man chiefly interested in himself and the lady referred to. He is without conviction or morality. He has always sided with the winning party, and his communications will be an indication of the strength of the Bolsheviks... I should certainly recommend his being allowed back into Russia."

Ransome arrived in Russia in October. He was arrested by the border guards and told that he was going to be shot as a spy. He told them that he was a close friend of Lenin and that he would be very angry if they killed him. "He won't be angry with me for obeying orders," replied the platoon commander. Ransome then explained: "If you shoot me and find out afterwards that it was a mistake, you won't be able to put me together again. If, on the other hand, you don't shoot me and find out afterwards that you should have shot me, that is a mistake you will easily be able to put right." On hearing this the Red Army commander released him.

Ransome arrived in Moscow on 22nd October. Within hours he had been reunited with Evgenia Shelepina. Ransome reported that he was convinced that the Soviet government would not be overthrown: "I walked daily in the streets, in the markets, and heard much said on the subject, but not a word that suggested the least belief that there would be any change in the established social order."

Over the next couple of days he opened up negotiations that would enable him to take Evegenia out of the country. Karl Radek reported to Ransome that Lenin had been upset by the content of Six Weeks in Russia. Radek defended Ransome by arguing that it was the "first thing written that had shown the Bolsheviks as human beings". Recently released classified documents from Russia show that Ransome and Shelepina were eventually allowed to leave in return for taking thirty-five diamonds and three strings of pearls (worth 1,039,000 roubles) and delivering them to Soviet agents based in Tallinn. The couple arrived in Estonia on 5th November, 1919. After handing over the treasure to agents of Comintern, they left for England.

For the next five years Ransome reported on Russia for both the Manchester Guardian and the Observer and after visiting the country in 1920 published the book, The Crisis in Russia (1921). In the book he concentrated on the Soviet Union's economic problems: "Nothing can be more futile than to describe conditions in Russia as a sort of divine punishment for revolution, or indeed to describe them at all without emphasizing the fact that the crisis in Russia is part of the crisis in Europe, and has been in the main brought about like the revolution itself, by the same forces that have caused, for example, the crisis in Germany or the crisis in Austria... We are witnessing in Russia, the first stages of a titanic struggle, with on one side all the forces of nature leading apparently to the inevitable collapse of civilization, and on the other side nothing but the incalculable force of human will."

Ransome went on to argue that Cheka was made up of "Jesuitical fanatics" who struck at random like lightning. He complained that in a raid on his flat in Petrograd they had destroyed "my collection of newspapers, every copy of every paper issued in Petrograd from February 1917 to February 1918, an absolutely priceless and irreplaceable collection". He wrongly claimed that the organization was not under the control of the government and were not being used to suppress political discussion on the future of the country: "I have never met a Russian who could be prevented from saying whatever he liked whenever he liked, by any threats or dangers whatsoever. The only way to prevent a Russian from talking is to cut out his tongue."

Ransome was in the Soviet Union during the Kronstadt Uprising. He was unmoved by the statement issued on 4th March, 1921, by the crew of the battleship, Petropavlovsk: "Comrade workers, red soldiers and sailors. We stand for the power of the Soviets and not that of the parties. We are for free representation of all who toil. Comrades, you are being misled. At Kronstadt all power is in the hands of the revolutionary sailors, of red soldiers and of workers. It is not in the hands of White Guards, allegedly headed by a General Kozlovsky, as Moscow Radio tells you." Writing in the Manchester Guardian Ransome followed the instructions of Felix Dzerzhinsky that the uprising had been fomented by a foreign power.

Life with Evgenia Shelepina

Ransome had been trying to obtain a divorce from Ivy Walker Ransome for sometime. On 28th February 1924 he wrote to Evgenia Shelepina: "This morning I saw the solicitors, and found it was as I suspected. The other side are holding up the decree until they get me to agree to what they want in the way of money. I have put in my proposal this morning, and I suppose next week we shall get an answer to it." Ivy rejected his proposal and demanded one third of his income. She also insisted on retaining Ransome's library as part of the deal. He wrote to a friend: "She knows only too well how to hurt most painfully. She is cruel." On 9th April, the divorce documents were exchanged.

On 8th May 1924 Ransome married Evgenia Shelepina in Tallinn. Ransome's mother wrote to her explaining: "You and I hold different views on certain subjects I know, but I want you to feel sure that this will not stand between us now that you are my son's wife. I send you my love, and I hope and pray that you and Arthur may have many years of peace and happiness in store. I know that you have gone through much together - that you have nursed him in sickness, stood by him in some of life's dark hours, and played with him in the bright ones - and that your influence over him has been wholly good. For all this I feel I cannot be too grateful and it fills me with the happiest hopes for the future. I do hope that when we meet we shall understand one another, and be very good friends."

Ransome purchased a house, Low Ludderburn, on the banks of Lake Windermere. He told his mother: "We are so overcome by finding ourselves in possession of the loveliest spot in the whole of the Lake District... It contains two rooms on the ground floor, plus scullery hole. Two rooms upstairs. A lean-to in bad repair, capable of being turned into a first rate kitchen... A lot of apples, damsons, gooseberries, raspberries, currants, and the whole orchard white with snowdrops and daffodils just coming."

Ransome continued to work for the Manchester Guardian. However, unwilling to travel the world, he wrote the newspaper's Country Diary column on fishing. He told his mother: "However, that may mean that they won't send me on any more of these horrible adventures. I am too old for them. I am all for slippers and a pipe, a glass of hot rum and a quiet life. Also I hate most horribly being away from my sterling old woman... And I hate being out of England."

Ransome continued to take a close interest in the Soviet Union. He disapproved of Joseph Stalin taking power and interpreted events as the "peasants" taking over from the "intellectuals". "What was happening in Russia was simply a final transfer of power to the class in whose name the Revolution had been launched." He was dismayed when he heard that his old friend, Karl Radek had been sent into exile. When the same thing had happened to Leon Trotsky he wrote in his notebook: "Could anything be meaner, to the man who made the army and won the civil war?"

Swallows and Amazons

In 1929 Ransome began writing novels for children. Swallows and Amazons was published in 1930. It had been written for the children of Dora Altounyan. She wrote to Ransome: "Swallows and Amazons arrived yesterday at 1pm and it is now 6am, and there have been very few hours of those 18 (sic) when it was not being read by somebody. I didn't ask Ernest what time it was when he came to bed - I myself read it till 11, and got to within seven chapters of the end. Well all we want to say is that we all liked it enormously." Malcolm Muggeridge reviewed it in the Manchester Guardian: "The book is the very stuff of play. It is make-believe such as all children have indulged in: even children who have not yet been so fortunate as to have a lake and a boat and an island but only a back garden amongst the semis of suburbia."

Swallows and Amazons sold slowly at first. The following year Swallowdale was published. However, it was not until his third book, Peter Duck (1932), that sales took off. A new book was published every year. This included Winter Holiday (1933), Coot Club (1934) and Pigeon Post (1936). According to Jon Henley the "children's books had sold more than a million copies by the time the last was published, and have sold many millions more since."

Arthur Ransome died on 3rd June 1967. The Autobiography of Arthur Ransom, edited by Rupert Hart-Davies, was published in 1976.

Primary Sources

(1) Roland Chambers, The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009)

Professor Ransome had tried to teach his eldest son to swim by throwing him over the side of a boat, and had the pleasure of watching him sink like a stone... Ransome acknowledged that his father was motivated only by the best of intentions, but revealed in one anecdote after another how his early development was impeded by an imagination so much less joyful and fertile than his own that rebellion was all but inevitable. Following the disastrous swimming lesson, he had taken himself, using his own pocket money, to the Leeds public baths, where he taught himself the backstroke in secret, only to be told when announcing the fact at breakfast that he was a liar. When the feat was eventually proved in situ, his father relented, but Ransome never truly forgave the accusation. He liked to remember the incident whenever amp aspersion was cast on his honesty.

When Ransome was done with private tutors, he was sent to day school in Leeds, then to the Old College at Windermere - his first taste of boarding school and a rude awakening. The headmaster, a friend of the family, liked to box, but Ransome was too short-sighted to defend himself and in consequence was called a coward. Neither was his performance in the classroom any consolation. As the son of a professor whose books were becoming standard texts at schools and universities, great things were expected of him, but Ransome, made miserable by homesickness, struggled with the simplest lessons. He ran away, but having nowhere to run to, came back of his own accord, gaining some comfort at the weekends by visiting a nearby aunt.

(2) Arthur Ransome, Autobiography (1976)

For a long time he (Cyril Ransome) walked with crutches, the foot monstrously bandaged. The doctors were slow in finding what had happened, probably because my father was so sure himself. In the end they found that he had damaged a bone and that some form of tuberculosis had attacked the damaged place. His foot was cut off. Things grew no better and his leg was cut off at the knee. Even that was not enough and it was cut off at the thigh.

(3) Arthur Ransome, Autobiography (1976)

I walked alone behind my father's coffin which, carried by six of his friends of unequal height, lurched horribly on its way. As the earth rattled on the lid of the coffin I stood horrified at myself, knowing that with my real sorrow, because I had liked and admired my father, was mixed a feeling of relief. This did not last. After the funeral more than one of my father's friends thought it well to remind me that I was now the head of the family with a heavy responsibility towards my mother and the younger ones. And my mother, feeling that she had to fill my father's place and determined to carry out his wishes now as when he was alive, told me (though I knew only too well already) of my father's fears for my character and her hopes that from now on I would remember to set a good example to my brothers and sisters.

(4) Arthur Ransome, Autobiography (1976)

It was March 1916 before I was given my first limited permission to visit the Russian front as a war correspondent. We went to Kiev and thence to the South Western Army Headquarters at Berditchev, where we met for the first time General Brusilov, the smartest-uniformed and most elegant of all Russian generals, later to be famous for his break-through in the west, and for the disasters his armies suffered in retreat.

I remember interminable driving in vehicles of all kinds along roads that war had widened from narrow cart-tracks to broad highways half a mile wife. Drivers had moved out of the original road to ground on either side of it not yet churned to mud. As each new strip turned to a bog, the drivers steered just outside it, so that in many places two carts meeting each other going in opposite directions would be out of shouting distance.

(5) Arthur Ransome made several visits to the Eastern Front in 1916 and 1917.

I saw a great deal of that long-drawn out front and of the men who, ill-armed, ill-supplied, were holding it against an enemy who, even in his anxiety to fight was no greater than the Russian's, was infinitely better equipped. I came back to Petrograd full of admiration for the Russian soldiers who were holding the front without enough weapons to go round.

(6) In 1916 Arthur Ransome visited the Eastern Front by air.

In August I had flown along the front in one of the old two-seated Voisin machines in which the passenger sat as if in an open canoe with a foot on each side of the pilot, in whose stupidity he had the utmost confidence. It was cold in the air and I well remember beating my hand against the outside of the canoe to get my fingers warm enough to take a photograph.

Our real trouble, such as it was, began when just before dusk we flew black to the place from which we had started. We began to spiral down and instantly there appeared puff after puff of smoke from shells sent up to meet us. The pilot suddenly turned the nose of the machine up, pointing with a grin to a small new tear in one wing. Presently he spiralled down again and again was greeted with shells from below. Once more we sheered off, this time with curses, and on coming back yet again we were, at last, recognised as friends and allowed to land.

I dined that night with the battery that had done the shooting, and sat next to the officer in charge. I complained that I did not think he had given me a very hospitable reception. "Perhaps not," he replied. "I'm very sorry, but really you ought to count yourself lucky, for usually when we fire at our own machine we hit it." He explained that the aeroplanes had been given to the Russian army because they were not good enough for the French. They were very slow and therefore easy targets.

(7) Arthur Ransome, Autobiography (1976)

Our Military Attaché in Bucharest was Colonel Thomson, who blamed himself a good deal for his share in bringing Roumania into the war. "They told me at home that I could ask for anything I liked if I brought Roumania in," he said ruefully when disaster was looming near," but I think it would be a little tackless if I asked for anything now."

I liked him very much and was shocked one morning to hear someone say that one of last night's bombs had fallen on the Military Mission. I went round at once. The bomb had blown away half the bathroom, which was on the upper floor, but had left the bath itself in the open, projecting over the ruins. The water-supply was still working, so Thomson was having his bath as usual.

Later, when it was clear that nothing could prevent a general retreat, Thomson picked me up in his car, and I found my knees lifted to my chin. "Have a look," said Thomson and I lifted the carpet to see that the floor of the car was covered with bottles of champagne. Thomson laughed. "Well," he said, "if it has got to be a retreat, I don't see why it should be a dry one.

Years later, in London, I met Thomson hurrying towards the Strand in civilian clothes and carrying a delicately tinted pair of gloves. He told me he was on his way to address a Trade Union meeting. I suppose I must have smiled and he must have noticed my glance at his gloves. "Yes," he said, "I know I don't look much of a Trade Unionist, but that can't be helped." He became Lord Thomson, Secretary of State for Air in the first Labour Government, and to the sorrow of all who knew him was killed on the first flight of the airship R.101.

(8) Hamilton Fyfe began reporting the war on the Eastern Front with Arthur Ransome in 1915.

The Russian officers, brutal as they often were to their men (many of them scarcely considered privates to be human), were as a rule friendly and helpful to us. They showed us all we wanted to see. They always cheerfully provided for Arthur Ransome (a fellow journalist), who could not ride owing to some disablement, a cart to get about in.

(9) In 1916 Arthur Ransome was employed by J. L. Garvin of the Observer.

Soon after I came back to Petrograd from the northern front, J. L. Garvin telegraphed asking me to become correspondent for the Observer. I was delighted and found things much easier. As correspondent for a Conservative newspaper I found doors wide open that would have been scarcely ajar for the correspondent of the Radical Daily News.

(10) Arthur Ransome, The Daily News (16th March, 1917)

It is impossible for people who have not lived here to know with what joy we write of the new Russian Government. Only those who know how things were but a week ago can understand the enthusiasm of us who have seen the miracle take place before our eyes. We knew how Russia worked for war in spite of her Government. We could not tell the truth. It is as if honesty had returned.

Today newspapers have reappeared, and their tone and even form are so joyful that it is hard to recognize them. They are so different from the censor-ridden mutes and unhappy things of a week ago. Every paper seems to be executing a war-dance of joy. The front pages bear Such phrases as "Long live the Republic," and "Long live free Russia".

The organization of the gigantic general election which must take place later will naturally take time. Meanwhile Russia will find her own mind, and I have no doubt that the decision will be worthy of the revolution that made it possible.

(11) Arthur Ransome, The Daily News (12th April, 1917)

The whole conference stood and cheered while she came in on the arm of Kerensky, who looked very ill and trembled with excitement. He was followed by other leaders and representatives of the army and the fleet and spoke in greeting. Many broke down altogether. The Grandmother of the Revolution is a little kindly old lady with nearly white hair and pink cheeks who laughed and cried as she kissed them. At last she made a short speech urging that Hohenzollern (the Kaiser) should not be allowed to conquer what had been taken from the Romanovs. I have never seen such enthusiasm. Soldiers and sailors leapt from their places and rushed to the tribune, and in some cases kneeling before her cried, "we have brought you from Siberia to Petrograd. Shall we not guard you? We have won freedom. We will keep it." She gave away some roses from the bouquet with which she had been met at the station and I saw a soldier who had only secured two petals wrap them up in paper while tears of excitement ran down his face.

(12) Lola Kinel, Under Five Eagles (1937)

It was the first bachelor room I had ever seen; it had a desk and typewriter in one corner, in another a bed, night table, and dresser all behind a screen; then a sort of social arrangement, consisting of an old sofa and a round table with some chairs around it in the centre.

And books. They were everywhere heaped on the sofa and even on the floor. Among these books I found occasionally torn socks. I used to pick them up gingerly in my gloved hand and wrap them in a piece of newspaper.

"Doesn't anyone ever mend your socks for you?" I asked one day.

"No. Don't bother to pick them up. I wear them and throw them away when they get torn. The maid forgot to take them away."

"But then you must buy an awful lot of socks."

"I do. These Russian laundresses never bother to mend things. I live like a wild rabbit."

"And look at your desk - look at all this dust. Doesn't the maid ever dust here?"

"I would wring her neck if she did. She daren't touch my desk," he said with the air of a fanatic threatened with some danger....

His own Bohemianism was not a pose but seemed real. He had, I remember, a thorough contempt for men who dressed well, or the least conventionally. He forgave women if they were pretty, but he preferred most Russian women, who do not pose and are simple, to English girls. For England he seemed to have a queer mixture of contempt, dislike, and love. He was clever, yet childish, very sincere and kind and romantic, and on the whole far more interesting than his books.