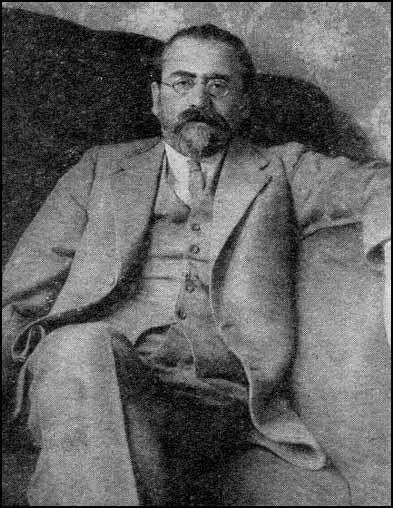

Theodore Rothstein

Theodore Rothstein, the son of Theodore Rothstein was born in Kaunas, Lithuania, on 14th February 1871. The Jewish family suffered from persecution under the rule of Tsar Alexander III moved to London in 1891.

Rothstein was a socialist and in 1895 he joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Other members included H. M. Hyndman, Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, William Morris, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, Helen Taylor, John Scurr, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Frank Harris, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillet.

On the assassination of Vyacheslav Plehve, the Minister of the Interior in Russia, he wrote in The Social Democrat: "Blood at the beginning, blood at the end, blood throughout his career - that is the mark Plehve left behind him in history. He was a living outrage on the moral consciousness of mankind, a sort of a yahoo who incorporated in him all that is bestial and fiendish in human nature; and no wonder the world breathed freely when at last he has been removed. Still it is not merely from the moral side that Plehve is to be judged. Plehve was both the product and the representative of a political system, and it is in that light that his career and personality acquire their historical significance. What must be that system which produces and places in its centre, as its main driving force, a monster such as Plehve was? The civilised world whose vision has been cleared by the events in the Far East, passed a judgment on that system at the same time that it passed it on Plehve: the system is rotten if its only strength lies in the executioner's arm. It is, indeed, the consciousness of this fact more than anything else that has guided the attitude of the capitalist press towards the assassination of Plehve; and this in itself constitutes a sinister mene mene to the absolutist régime in Russia."

Rothstein was an early critic of other socialist parties such as the Labour Party. He did give praise to those like Victor Grayson, who urged more revolutionary policies. He argued in August 1909: "Grayson is still quite a young man, about 27 years old, gifted, full of temperament, a born agitator, but without any sort of theoretical knowledge, no Marxist – more inclined to be an opponent of Marxism – in short, a sentimental Socialist at an age when the wine is not yet fermented. Like all Socialists of this type – and the type is a historical one, dating far back beyond our period – he represents more the tribune of the people than the modern party man, and without being an anarchist or syndicalist, he has a great horror of parliamentarism and of the planned political struggle, which he looks upon as dirty jobbery. This horror seems to be very wide-spread in England, in spite of the prevalent fetish-worship of Parliament, and is caused by the lying and deceitful tactics of the bourgeois parties."

Rothstein became a journalist and worked for a variety of newspapers including the The Daily News, The Manchester Guardian, Justice and The New York Call. He also also wrote for left-wing publications in Europe. During this period he became a friend of Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders. Rothstein was also active in the National Union of Journalists and was a strong opponent of the First World War and a supporter of the Russian Revolution.

According to Roland Chambers, the the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): "By 1917, Rothstein, a close confident of Lenin's, was both a senior executive of the British Socialist Party and a Bolshevik, which made it that much more astonishing that at present he was employed by the British War Office in the highly sensitive position of translator and interpreter." Chambers reported that the journalist, Arthur Ransome, had sorted him out with a view to gaining a letter of introduction to the Bolshevik leaders. He agreed and wrote: "Mr Ransome is the only correspondent who has informed the English public of events in Russia honestly."

In July 1919, Rothstein published an article in The New York Call in praise of the Russian Revolution. "This miracle has been accomplished by the genius and daring of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution which has now, for more than eighteen months, been transforming the world of ideas, the world of action, in a way never paralleled by any event, by any movement in previous history. Who but a Goethe felt the immediate effect of the great French Revolution at the battle of Valmy in 1792, that is, three years after its beginning? And was any contemporary in the least conscious of the effect of the teaching - we shall not say of semi-mythical Jesus and his insignificant handful of followers - but of St Paul the real founder of Christianity as a world religion? Yet here, less than two years after the accomplishment of a revolution in a far distant and almost unknown country, in spite of the immense amount of force of counter-influences, in spite of an almost impenetrable material and moral blockade erected by its enemies, in spite of an almost opaque atmosphere of poisonous gases, created by the lies calumnies and distortions of these same enemies - in spite of all this, the whole world of Labour is already feeling and responding to its stimulus, so that even in its most backward sections, those of this country can longer restrain their emotions, and have decided to come out into the streets to demonstrate them?... The Bolsheviks of Russia, under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, have, by the courage of their act performed the necessary operation, and every day that passes and brings with it the continuation of their rule sees the further and wider penetration of the revolutionary proletarian ideas which are inscribed on their glorious banner. And within every such new day we feel that their rule is going to continue and to gather strength inside and outside, all the efforts of the enemy, internal and external, notwithstanding."

On 31st July, 1920, Rothstein helped form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Early members included Tom Bell, Willie Paul, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, J. T. Murphy, Arthur Horner, Rose Cohen, Tom Mann, Ralph Bates, Winifred Bates, Rose Kerrigan, Peter Kerrigan, Bert Overton, Hugh Slater, Ralph Fox, Dave Springhill, William Mellor, John R. Campbell, Bob Stewart, Shapurji Saklatvala, George Aitken, Dora Montefiore, Sylvia Pankhurst and Robin Page Arnot. McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. It later emerged that Lenin had provided at least £55,000 (over £1 million in today's money) to help fund the CPGB.

Soon after the establishment of the CPGB Rothstein returned to Russia. On 6th January 1921 he was appointed as the Ambassador to Tehran. The following year he became a member of the Collegium of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs.

Theodore Rothstein died on 30th August 1953.

Primary Sources

(1) Theodore Rothstein, The Ethics of Sex Relationships (May, 1899)

In venturing to approach the above subject I do not think I need offer any apology for adding one more name to the long roll of those who from the time of Plato down to our own have made attempts to grapple with it, and for hoping - as, in fact, every earnest writer is in conscience bound to hope - to succeed where my predecessors have failed. The problem is one of profoundest interest and importance to mankind; indeed, throughout the entire range of human life and thought we can hardly find another which has stirred so deeply the passions of men and baffled so completely the work and wisdom of ages; but this, if at all taken as a measure of our attitude towards it, ought rather to serve as an incitement to our efforts and bid welcome to every endeavour, however small, humble, and obscure, than deter us from any further attempt in this direction. And especially is it so at this very moment. We are on the eve of a great social upheaval; on the rising waves of the transition tide our boat is being tossed to and fro, and sharp must be the eye and firm the hand of the steersman who wants to land in the quiet harbour. Our ethical consciousness is put under the severest strain; there is a wide discrepancy between it and the stern reality of fact, and unless we keep our heads clear and possess nerve enough, we may wreck our frail vessel of life on the cliffs and treacherous sands of moral wrong....

In no other domain, however, is this discrepancy greater, and consequently felt more acutely, than in that of the right and ought of sexual relations. We have outgrown by now the old conception handed down to us by ascetic Christianity which regarded those relations as in themselves sinful and unholy, and come to recognise the truth that sex-love is an organic want and function, having the same right to satisfaction and exercise as any other in the physiological equipment of man. Even more; with the advent of a new morality which proclaimed the full and healthy development of our entire physical and spiritual nature to be the supreme good to be worked and striven for, the suppression of the sexual impulse has become in the eyes of men a thing as odious as it was before virtuous. No person, says our new conception of life, on reaching maturity can be held in duty bound to eliminate that important item of his nature; more than that, he has no right to do so if he ever wishes to live a life rich in all human experience - that is, to live an ethical life. But how is this to be achieved? How is this to be realised? Happy the man or woman who meets in his or her life-course some one to their liking But what of the rest? There are thousands upon thousands in every rank and class of society who for some reason or other are condemned to walk their life long in lonely paths, standing little or no chance of ever meeting one to love and be loved by, and of tasting to the full of the cup of human happiness. What about them? Are they destined to play the part of children disinherited by blind and cruel mother Nature, or may they fight for their birthright by some other means? What are they to do? Their right to sexual happiness is absolute; is their ought also absolute in the sense of furnishing a complete justification for every and any means they might use with a view of asserting that right? May they, for instance, have recourse to prostitution - apart from any humanitarian consideration attached to it - in case their physiological need cries for satisfaction? Or, if this be not allowed, can, say, mutual consent or mutual respect form the basis on which the sexual impulse may find its opportunity for realisation?

Such are the questions that beset the modern man standing on the threshold of the twentieth century. They are no more academical than life itself. Children of reality, creatures of the time, they have been called forth by the rise of a new ethical ideal to which the present state of things lends no hope of ever being attained. As such, they stand and wait and implore and press for an immediate answer. What, then, is that answer to be? How are we going to realise the physiological and moral requirement of an emancipated sexual life under conditions which give a favourable chance but to a selected few?

(2) Theodore Rothstein, The Social Democrat (August, 1904)

Plehve assassinated, and not a word of regret even from the Liberal Press of this country. For once the Nonconformist conscience forgot its thrill of horror and, in the teeth of the traditional de mortuis nil nisi bonum, declared drily and uncharitably: It serves him right. It is, indeed, a monster "dripping blood from every pore" that has been removed from the stage of modern history. He it was who acted as the "examining magistrate" in the case of Zhelyabov, Perovskaya and the others who had taken part in the assassination of Alexander; he it was, who as the Assistant Minister of the Interior diabolically conceived and carried out the anti-Jewish outrages in Southern Russia in 1881 and 1882; he it was who, as the Secretary of State for Finland, by a single stroke of the pen suppressed in 1899 the constitutional liberties of that country, solemnly guaranteed, as they were, by treaty and by the oath of the Czar; he it was who, on being appointed, in 1902, Minister of Interior in the place of the Sipiaguine, shot by Balmashov, at once introduced a regime which resulted in the ruthless suppression of the peasant disturbances of the Kharkov and Poltava provinces, in the flogging of May demonstrators at Wilna, in the wholesale murder at Zlatoust, and in the barbarous treatment of strikers at Tiflis, Baku, and Ekaterinoslaff; lastly, he it was, who was directly responsible for the horrors of Kishineff and Gomel - horrors that remind one of the darkest period of the Middle Ages. If to this be added the numberless other outrages and acts of terrorism committed against various public bodies as well as single individuals who in any way dared to assert their independence of speech or thought, we may well say that there is in modern times but one name that is worthy to rank along with his, and that is the Duke of Alva. Blood at the beginning, blood at the end, blood throughout his career - that is the mark Plehve left behind him in history. He was a living outrage on the moral consciousness of mankind, a sort of a yahoo who incorporated in him all that is bestial and fiendish in human nature; and no wonder the world breathed freely when at last he has been removed.

Still it is not merely from the moral side that Plehve is to be judged. Plehve was both the product and the representative of a political system, and it is in that light that his career and personality acquire their historical significance. What must be that system which produces and places in its centre, as its main driving force, a monster such as Plehve was? The civilised world whose vision has been cleared by the events in the Far East, passed a judgment on that system at the same time that it passed it on Plehve: the system is rotten if its only strength lies in the executioner's arm. It is, indeed, the consciousness of this fact more than anything else that has guided the attitude of the capitalist press towards the assassination of Plehve; and this in itself constitutes a sinister mene mene to the absolutist régime in Russia.

Of course, it is not by political assassinations that freedom will be established in that great and unhappy country. You cannot exterminate vermin unless you change the conditions which favour its existence and reproduction. By exterminating individual specimens of it you merely substitute two living ones for one killed, whilst at the same time running the risk of neglecting and delaying the more important work. Political assassinations are mainly valuable from a moral point of view, as showing that there is still life and sense of human dignity in the down-trodden nation. They are thus a sort of vindication of national honour - precious tokens of a great future. But freedom itself will have to be won by other means - by the people at large fighting the system itself. Our Social-Democratic comrades in Russia are precisely engaged in this kind of work, and it is to them mainly that we look for the final onslaught on the moribund autocracy. In the meantime, we may well be thankful for having got rid of the most brutal instrument of that system; another such will not be easily found.

(3) Theodore Rothstein, The Social Democrat (February, 1905)

Henceforth the Socialist movement in Russia became a political movement – a movement for the overthrow of the autocracy. What were its methods? Naturally those that were dictated by the then-prevailing “Social-Slavophil” conceptions. If the Russian people are born communists and democrats, then autocracy has really no root in the national soil and can be overthrown by a few well-aimed blows. But from whom should these blows proceed? From the people? But experience has shown that it is very difficult to make it rise – nay, that it is very difficult to carry on a propaganda amongst it for that purpose on account of the very same “external power” which it is proposed to remove. Should the blow proceed from the town proletariat? According to the teachings of Marx that would have just been the proper class which could take upon itself that work. Unfortunately, it can scarcely be said to exist. Who, then, should engage in a fight with the autocracy? Well, there is only one class which could do it, and that is the very same class which had carried before the gospel of discontent to the people – the revolutionary educated youth. They are few in numbers, it is true, but they can adopt the methods of conspiracy, and for that large numbers are not required.

Thus arose the “terror” – that dramatic duel between a handful of conspirators and the powerful autocracy, which filled with astonishment the whole world. We know how it ended. After a series of attempts, each more daring than the other, the party made a supreme effort and delivered its most tremendous blow. Now or never, everybody thought, and it was – never! Why? Did the party become exhausted, as some say, or were the Liberal classes too cowardly to come forward and demand a Constitution, as others assert? Both these reasons were true, but they were true because autocracy was not such a rootless growth, as it was supposed, and has revealed itself as such at the very moment when it was apparently stabbed in its very heart. Autocracy was but the political complement of the social order which lay at the base of Russian society, and no sooner was one of its heads struck off than another grew instantly in its place. There is in social organisms, as much as in natural, an inexhaustible fountain of creative power, and so long as their structure remains unchanged, the same growths will appear one after the other, much as you may try to stop them.

We thus arrive at the beginning of the eighties. Consider the situation – the People’s Will Party lying on the ground broken and exhausted, reaction rampant, all that was but a short time ago hopeful, disheartened and embittered. Where shall we turn for light and guidance? To the people? It is mute. To the working-class? There is none. To the educated classes? They are all full of pessimism in the consciousness of their weakness. What, then, next? Is all hope to be given up? Is there no salvation for Russia? At this moment of darkness and despair a new and strange voice resounds through the space – a voice full of harshness and sarcasm, yet vibrating with hope. That is the voice of Russian Social-Democracy.

From whom did it proceed? From a handful of political refugees on the banks of the Geneva lake. And what did it announce? It announced that all this talk of a special destiny and mission of Russia is sheer nonsense, that Russia will have to go exactly the same way as other nations, that she will neither be spared her capitalism nor the proletarisation of her masses: that the village community, so far from being able to develop into a “form of the future,” is, on the contrary, the most formidable obstacle in the way of social and political progress; that, for the rest, it already disintegrates – and that rapidly – under the pressure of economic changes introduced by the first acts of capitalism; that salvation is only to be expected from the proletariat acting in its own class interests; and that, lastly, this salvation will not be the social revolution, but will take the shape of an ordinary humdrum “bourgeois” political freedom! We can imagine what a courage it was required to throw in the teeth of all tradition and all the then-prevailing views such heterodox opinions, and that, too, with an unheard-of strength and tone of certainty. We can also imagine what a storm of indignation they aroused – especially as they came at a moment when the traditional creed was doubly dear now that the enemy had outraged it. What – rang the universal cry – Russian Social-Democracy? But a more ridiculous idea could not have been born in a human brain. Social-Democracy presupposes a proletariat; and where is the Russian proletariat? It is simply an attempt on the part of some doctrinaires to transplant to the Russian soil a growth which is totally foreign to it. Or is it something still worse than that? Is it, perhaps, a move on the part of the bourgeois ideologists who wish to sweep away our ancient foundations of life – the village community and the rest, in order to make room for capitalism? It looks like it. We have no capitalism at present and no proletariat; consequently, those who wish for the latter must wish for the former. Our so-called Social-Democrats are, therefore, nothing more than knights-errant of capitalism – heroes of “primitive accumulation,” social enemies of the Russian people. They do not want Socialism – they merely want a political constitution which should give the power to the bourgeoisie. No, a thousand times, no! Our village community is our most precious national treasure, and we shall not give it up for the greater glory of capitalism and of a German doctrine!

In this and similar strain the case was “argued” against Social-Democracy, and there was no more odious name at the time than that of a Social-Democrat. In vain did the latter point out that what opponents were accusing them of aiming at is actually taking place irrespective of anybody’s wishes – that, for instance, capitalism, in the shape of the usurer, middleman, & c., is irresistibly making its inroads into the very heart of the village community; that the peasantry is becoming more and more ruined every day; that the social cleavage amongst it is daily becoming more and more pronounced; that the masses, in consequence, are at an ever-accelerating pace undergoing the process of proletarisation; that the village community itself is no longer a community, but an instrument in the hands of the State and the local capitalists to keep in subjection the poorer peasants; that, so far from the proletarisation of the masses wiping out from their minds democratic and communistic ideals, it, on the contrary, frees their individuality from the trammels of patriarchalism and makes them susceptible to a higher political and social ideal. In vain, we say, did the Social-Democrats point this all out and invite their opponents to cast off the old chimerical and essentially reactionary dreams and instead look reality straight in the face, and base on that reality their socio-political activity. The opponents would not listen, they would continue to reiterate their ancient shibboleths and cast showers of abuse on the heads of the “disciples.”

Thus the controversy dragged on for a number of years. The old “Populists” would show by black and white that capitalism has no future before it in Russia, since all the markets of the world are already taken up by the other nations. They would also show statistically that the number of workers is insignificant and has no chance of growing. They would lastly taunt their opponents with fatalism and declare that their hopes of the future condemns them to inactivity. The Social-Democrats would reply by saying that capitalism largely creates its own market; that the number of workers is not so small as is imagined, and that with the disintegration of the village community autocracy loses its main prop and the efforts of even a comparatively small number of town-proletariat will suffice to bring it down. As for fatalism and the rest, the less the “Populists” speak of this, the better. It is they who believe fatalistically in the magic virtues of the village community, and it is they who are inactive, not knowing where to turn. The Social-Democrats, on the contrary, have plenty of work. They need not wait till capitalism shall have done all its work, but they can take up the proletariat as it is turned out from the villages, and educate it in the ideals of political and economic freedom.

Events soon proved that the Social-Democrats were absolutely right. Whilst the “Populists” were arguing against the possibility of capitalism and of a proletariat in Russia, and the People’s Will Party broke up in fragments (some of its members, recollecting their ancient kinship with the Slavophils, going over to reaction), capitalism and the proletarisation of the masses were making enormous strides, and everywhere, in all industrial centres of Russia, Social-Democratic organisations sprang up to carry the Socialist propaganda among the factory workers. Suddenly in 1895 a vast strike, embracing tens of thousands of textile workers, broke out in St. Petersburg, and following that, a number of similar strikes in all large towns. What was it? The old “Populists” were taken aback. Have we really got a capitalism and a proletariat? It looked uncommonly like it. At once Social-Democracy – or Marxism, as it was called in the “legal” press – acquired a tremendous prestige and spread like wildfire throughout Russia. The entire educated youth became converted to Marxism, and the latter became a veritable craze. The Press and the drawing-rooms became full of it, special reviews were established to propagate it, books pro and con. were published in enormous quantities, and such books as Beltov’s “Monistic View of History” – one of the cleverest books on Marxism in our literature – had a “tearing” success. Of course, the “Populists” did not give in at once, and some of their old guard carried on a campaign against the new craze with a passion and ability such as would have been worthy of a better cause. But little by little the old guard was left alone in its trenches and the younger generation joined the ranks of the Marxists. No doubt, like every craze, the movement did not last very long; it was preposterous to dream of Marxism in a “legal” dress, and for real revolutionary work but few were prepared. And so the majority gradually cooled down or became infected with Bernsteinianism (another craze of the time), whilst the minority simply turned Liberal. That, however, did not in the least injure the revolutionary Social-Democracy – the Social-Democrats felt themselves masters of the situation, and took to their work with an increased zeal. In 1898 they even made an attempt to form a united Social-Democratic Party, and, though the attempt turned out to be premature, it still spoke volumes for the extent and vigour of the movement. Now there could no longer be any talk of resuscitating the old People’s Will Party – Social-Democracy was trumps!

Yet it was precisely at that very moment that the bastard movement called the Revolutionary Socialist Party first made its appearance. These were the old familiar “Populists,” still enamoured of the peasantry and the village community, who, being no longer able to dispute the existence of capitalism or the strength of the proletariat, conceived the happy idea of combining all the three things that were “good” in the programmes of the preceding three revolutionary parties in Russia, viz., the ideal of peasant communism of the Land and Liberty Party, the idea of the revolutionary proletariat of the Social-Democracy and – the ingenuity of it! – the conception of terrorism as the means of the revolution, of the People’s Will Party! How these three things, so logical, taken by themselves, in their original respective programmes, were in practice to be amalgamated into one mixture; how, for instance, the proletariat could be made revolutionary on behalf of the ideals of the peasantry, or how the conspirative exercise of terror could hang together with a class movement, all this remains a mystery to this day; the only practical solution which the Revolutionary Socialists have given to the difficulty was by establishing a separate organisation (alas, in many cases, mythical!) for carrying on terrorist acts (thus making the revolution doubly sure!), by instigating the peasantry to riots in the name of Land and Liberty, whilst at the same time preaching to the proletariat the class war. As a result we have a double or even treble system of revolutionary book-keeping, which finds its counterpart in the language which they speak to European and Russian audiences respectively, and a continual spasmodic oscillation, now towards terror, then towards peasants’ riots, then again towards propaganda among the proletariat, and last, but least, towards compromises with bourgeois parties!

And now, at last, we reach the present day. There is no denying the fact that within recent years the Revolutionary Socialists have acquired a reputation far beyond their intrinsic worth. Whilst Social-Democracy was silently impregnating the proletarian with class-consciousness and preparing it by means of street demonstrations for a general attack on Czardom, the Revolutionary Socialists have startled the world, first, by the organisation of peasants’ riots in the southern parts of Russia, and then by a series of daring attempts on the lives of some of the most unscrupulous representatives of autocracy. More particularly was the world taken in by the assassination of von Plehve, than whom there was no more hateful figure throughout Europe. This is scarcely to be surprised at. The world did not know Russia nor the forces that were really shaping her destiny. Partly despairing of any other means of salvation, partly impatient of the slow work of social forces, it greeted with delight the removal of such men as Plehve and thought that, if anything, it was terroristic acts like these that are likely to disorganise the autocratic system of government. And the Revolutionary Socialists themselves began to take themselves quite seriously. The Russian Liberals, who, like all other Liberals, have no understanding for the class movements of the proletariat, looked in their own helplessness with great sympathy upon the acts of terrorism, and money flowed from all sides to the “war chest” of the Revolutionary Socialists. What was Social-Democracy to them? A doctrinaire movement engaged in theoretical hair-splitting, but with no “go” in it. “Everyone,” declares in a leading article the Revolutionary Russia, the official organ of the Revolutionary Socialists, as recently as July of last year, “everyone who has followed during recent years the development of contemporary social-revolutionary thought both in the West of Europe and in Russia, cannot fail to acknowledge that the so-called orthodox and only revolutionary Marxism is living through its last and really tragical days of its existence .... In its instinctive endeavour to save at any cost its obsolete dogmas, its extremely narrow methods both in the domain of theory and in that of practice, the orthodox Marxist literature has fatally condemned itself to spiritual sterility, to the involuntary sin of ‘double-tongueness’ and to the voluntary sins of casuistical hair-splitting and hypocritical diplomacy.” Such was the opinion held by the Revolutionary Socialists of the Russian and International Social-Democracy, and it was, unfortunately, shared by many who ought to have known better.

And now the 22nd of January, with all that follows it at the present moment, has given the direct lie to these impudent assertions, and proved finally that it is Social-Democracy which will deliver Russia from her secular slavery. At first it was thought that it was a spontaneous rising of the St. Petersburg proletariat with which Social-Democracy had nothing in common. Now it is known that even in St. Petersburg Social-Democracy had a direct hand in the movement, whilst in all other towns it is only Social-Democracy that is organising and leading the movement. The Russian proletariat is now a class-conscious agent of the Revolution, and this we owe exclusively to the Russian Social-Democracy. It may well be – and, in fact, it is so – that in St. Petersburg a great portion, perhaps the majority, of those who went on the 22nd to the Winter Palace, were not Social-Democrats. But the very nature of their programme containing Social-Democratic demands as well as the fact that one single day sufficed to open their eyes to the real state of things, showed that the Social-Democratic propaganda in the past has not been in vain.[1] Social-Democracy, which once upon a time sprang up in the minds of a few “intellectuals,” is now leader of the popular Revolution, and no Trepoffs will be able to put it down. Autocracy has hitherto ruled, thanks to the acquiescence of the people, now it will have to rule against the will of the people – and that is a mightily difficult task!

We can rest quite assured as to the final issue of the Revolution. It has been foreseen when not a glimmer of it could be discerned with the naked eye, and the realisation of the forecast will carry us to the end. No more uncertainty, no more despair, no more pessimism – the “dogma” has proved correct and the “dogma” will triumph to the very last! It is the proletariat which has risen in its class interests against autocracy, and it is the proletariat which will make an end of it.

(4) Theodore Rothstein, The Social Democrat (March, 1908)

When all is said and done, however, the charge preferred by Marx and Engels against the policy of the S.D.F., as distinguished from its leaders, remains. That charge was, that its members regarded their Socialism as a dogma to be forced down the throats of the working class, and not as a movement which the proletariat has to go through with the assistance of the more conscious Socialist elements. The latter must accept the working-class movement at its starting point, go hand in hand with the masses, give the movement time to spread and consolidate, be its theoretical confusion never so great, and confine their efforts to pointing out how every reverse and every mistake was the necessary consequence of the theoretical inadequacy of the programme. As the S.D.F. did not do so, but insisted on the acceptance of the dogma as the necessary condition of their co-operation, it remained a sect and “came from nothing, through nothing, to nothing.”

Such was the charge. Was it justified? There can be no doubt that the Socialist policy as laid down by Marx and Engels in the above words was theoretically perfectly correct. It was in the Communist Manifesto that they had first proclaimed the principles of Socialist tactics by declaring that the Communists did not form a party separate from the general working-class movement, but represented in that movement its own future. One cannot help thinking, however, that when urging the same ideas thirty and forty years later upon the English Socialists they did not take sufficiently into account the difference in the conditions as between Germany of 1848 (it was primarily for German Communists that the Manifesto was composed) and England of the eighties. In Germany the proletariat was at the time mentioned only just evolving. It was largely as yet a raw material, confused but plastic, whose chief disadvantage, from the Socialist standpoint, consisted in the multitude of petty bourgeois notions under which it was still labouring. It was clearly the duty of Socialists to bring light into those masses by moving together with them much as a good pedagogist moves in the midst of his children, guarding them, when possible, against mistakes, but never lecturing them, never placing himself above them, always keeping patience with them, invariably allowing them to learn through mistakes and failures. This is the soundest line of conduct in all young capitalist countries, such as Germany was half a century ago, or America was in the early eighties, or Russia is at the present moment. It was also the policy of the Chartists in the latter thirties and early forties, when the British proletariat had just discovered for the first time its fundamental distinction from the middle classes.

Very different was the position in England in the eighties, when the Socialist movement was started by Hyndman and the S.D.F. The English working-class was no longer a raw material which one might help to shape according to one’s better light. It was well organised in trade unions, it had behind it a long and very pronounced historical experience, it had its traditions and acquired habits of mind – in short, it was a manufactured article, as it were. And what was still more important, those traditions and habits of mind were thoroughly bourgeois – not negatively-bourgeois as is the case with a working-class still unripe, but positively-bourgeois as comes from over-ripeness. In these circumstances what could and should have been the policy of the Socialists? The principles laid down in the Communist Manifesto were correct as ever – only they were in the English conditions of the eighties utterly inapplicable. By no permanent and intimate co-operation with the masses, such as was urged by Marx and Engels, could the Socialists have hoped “to revolutionise them from within”; on the contrary, what would have been achieved was merely the adaptation of the Socialists to the mental level of the masses which spelt not confusion” not theoretical unripeness, but Liberalism. Those who doubt this need only turn to the fate of those numerous ex-Socialists who have left the S.D.F. and “gone over” to the masses, but are now to be found in the ranks of the two bourgeois parties. The English working-class was not to be revolutionised from within, as many attempts, started with the blessings of Engels. himself, have proved by their dismal failure. Indeed, the International itself, in so far as Marx, in starting it, had the hope of “revolutionising” the British trade unions, was a ghastly failure – not only did the trade unions prove obstinate in their Liberalism and bourgeois Radicalism, but they ultimately withdrew, and the whole business collapsed.

No, however lamentable it may appear now, a certain intransigence, a certain modicum of impossibilism, was in those days not only inevitable but really necessary, if the Socialist movement was to subsist. It was all very well for Engels – and the idea is still entertained largely even now – to ascribe the impossibilist tendencies of the S.D.F. of that time to the baneful influence of Hyndman and other leaders; rather were Hyndman and his colleagues themselves semi-impossibilists only because the condition of their work demanded it. No other organisation, with totally different men at the top, would have conducted itself differently; if it had, it would have disappeared where the S.D.F. had survived.

(5) Theodore Rothstein, The Social Democrat (August, 1909)

At the present time a great confusion exists in the ranks of the Independent Labour Party (I.L.P.). The four most important members of its National Council – Keir Hardie, MacDonald, Snowden and Bruce Glasier (editor of the party organ, the “Labour Leader”) – have, in consequence of the criticism of their policy as leaders of the Party which was expressed at the Easter Conference, demonstratively retired from office. In an open letter addressed to the members of the Party they point out that confusion has existed for some time, caused by the formation within their ranks of a group who do not know what they want, who to-day applaud the Labour Party, and to-morrow demand the formation of a new Socialist Party, who upset the minds of the comrades and undermine their confidence in the leaders by their criticisms and ugly allusions and erroneous statements. How could the business of the Party be carried on under such circumstances? It is indeed not a question of the tactics of the Party – these were laid down once for all when it was founded – but only as to whether the Party is desirous of carrying out these tactics, of insisting upon loyalty to the latter, and of rejecting any actions or methods not in agreement with them. But it is exactly on this point that the Conference has in some instances not supported the Council, thus leaving them, the writers of the letter, no choice but to resign the mandates given by the Party.

Horrible! What can have happened? What is this mysterious group which is confusing the spirits of the Party, and has driven the four most respected leaders and founders of the Party out of the “responsible” posts of the Party Ministry? The proclamation of the four – the quartette, as it is now called in I.L.P. circles – does not mention any names, but all the world knows that the allusion is to the Grayson group. Now, who is Grayson? Who constitute his group? Wherein consists their disruptive activity?

Grayson is still quite a young man, about 27 years old, gifted, full of temperament, a born agitator, but without any sort of theoretical knowledge, no Marxist – more inclined to be an opponent of Marxism – in short, a sentimental Socialist at an age when the wine is not yet fermented. Like all Socialists of this type – and the type is a historical one, dating far back beyond our period – he represents more the tribune of the people than the modern party man, and without being an anarchist or syndicalist, he has a great horror of parliamentarism and of the planned political struggle, which he looks upon as dirty jobbery. This horror seems to be very wide-spread in England, in spite of the prevalent fetish-worship of Parliament, and is caused by the lying and deceitful tactics of the bourgeois parties. It is more to be ascribed to this horror than to firmness of principle, that Grayson, when put up as candidate at a bye-election in the summer of 1907 by the workers of Colne Valley, a Yorkshire constituency, fought for the mandate as a declared Socialist upon an openly Socialist programme, and rejected the compromise proposed by his National Council to appear before the public as a mere “Labour candidate” according to the arrangement of the Labour Party bloc. In spite of his being boycotted by the administration of his own party, as well as that of the Labour Party, and having candidates of both the bourgeois parties opposed to him, he was elected and came into Parliament, the first representative of the workers to get in on a Socialist ticket; thus proving that the hushing-up policy of the National Council of the I.L.P. and their trade unionist colleagues of the bloc of the Labour Party is not a necessity, and occasioning great joy in the S.D.P., as well as among the Socialist elements in the I.L.P., but at least equally great annoyance among the National Council of the latter.

Since that time Grayson has come to be in permanent opposition o the heads of his party, as well as the Labour Party group in general. As he did not join the latter, it boycotted him, and on the few occasions when he spoke in the House (as a Parliamentarian he was chiefly remarkable by his absence) he always came into collision with it. As, for instance, when the English King’s visit to Reval was discussed. The Labour fraction, encouraged by the Radicals, had decided on an interpellation, and as polite people (unlike the Irish who always force their questions upon the “Honourable House”) they entered into negotiations with the Government as to when and under what conditions they would allow this interpellation to be discussed. The Government said they would be glad to meet the wishes of the Labour fraction; only the debate must be closured at a certain hour by the leader of the Labour Party himself, and besides, the speakers must observe a respectful tone towards the King. The group joyfully accepted the conditions, and during some hours made their speeches, which were a curious mixture of attacks upon the Anglo-Russian friendship, and loyal songs of praise to King Edward. The time for adjourning the debate had already passed, but two Liberals spoke in succession, and the leader of the Labour Group, Henderson, showed no signs of interrupting them, Suddenly there arose from his seat, the “enfant terrible,” Grayson, who might well be expected to adopt a sharp tone against the King. Immediately at a sign from the Government, Henderson rose and closured the debate. Grayson protested, but was not allowed to speak.

Grayson came into collision a second time with the Labour Party on the question of unemployment. The Labour Party had neglected this question very much, while it had supported with great enthusiasm the Government’s Licensing Bill. The protests against this outside the House were becoming more frequent and violent, and one fine day when the whole House was deep in discussing a paragraph of the Licensing Bill, Grayson appeared upon the scene and announced to the House an obstruction according to the Irish pattern if it would not occupy itself, instead of with trivialities, with the unemployment question. Grayson’s appearance was unexpected, and one could justly reproach him that he, who never appeared in Parliament and had let pass earlier and much more suitable occasions for a protest, had no right to dictate to his colleagues as to what they should occupy themselves with. Still, this formal reason could only be sufficient to prevent the Labour Party supporting him in his unasked-for and unforeseen protest. But these gentlemen went further, and when the leader of the House, the Prime Minister Asquith, moved Grayson’s suspension, none of them uttered a syllable of protest, some refrained from voting, and the others voted for the proposition.

This, then, is Grayson. No extraordinary hero, as you see; no pioneer; though, on the other hand, not quite an ordinary human being. Whence, then, comes his popularity? How did he manage to create a state of mind in his party by which the most respected leaders have been defeated? The answer is, he has created no state of mind; he has only given expression to that state of mind which was already present; and that is why he has become popular. Perhaps the same state of mind could have been expressed much better and more worthily by a different person. As a matter of fact, the manner in which he gives expression to it is too theatrical, sometimes bordering on caricature. Still, he it was who distinctly voiced the state of mind, and he is made much of by those who agree with him – as a symbol, a standard. Nothing could be more mistaken than to see in him the leader of an opposition. He is no leader, neither can he become one. He is but a point of crystallisation, round which those elements group themselves who have something they wish to express.

What is that state of mind? Who are these elements? The state of mind is: Discontent with the tactics adopted and carried on during the last few years by the I.L.P. leaders towards the Labour Party. Here we reach a much discussed topic, which was also raised in the “Neue Zeit” a short time ago. How should a Socialist Party behave towards a Labour Party like that in England? As Marxists we all indeed know that Socialism can only succeed as a labour movement, that Socialists do not constitute a special organisation opposed to the other labour parties, and that the Socialist idea and the organised proletariat united into a class party must go together, like – to use the striking expression of Comrade Kautsky – the connection between the final goal and the movement. In all Continental countries we have acted upon these principles, but not in England, where their application met with a hindrance in the form of the peculiar historic facts. For while in other countries it was the Socialists themselves who for the first time organised and mobilised the hitherto chaotic, or, to be quite correct, amorphous mass, the proletariat in England had already been organised and actively engaged in the political struggle for decades before the modern Socialists appeared in the historic arena. Therefore Socialism on the Continent was never for a moment separate from the general labour movement, but stood, on the contrary, in its midst as its central force, while in England it arose as something different – even something opposed. What were the English Marxists to do under these circumstances? Should they merge themselves in the Labour Party? But there was no such thing at the beginning of English Marxism, for the few trade unions which engaged in political action did not at that time constitute a special party, but only provided from among their ranks members and candidates for the Liberal Party. All then that the Socialists could do was to seek to win over the masses to themselves; and that they did. Were they successful? No. Marx himself did not succeed when he tried to unite the English labouring masses to the International. As long as the English trade unions were fighting for the suffrage, as a means of securing their right of coalition, it seemed as though Marx’s attempt were destined to succeed. But no sooner was the suffrage – and what a meagre suffrage! – won, and the right of coalition secured, than the unions left the International, and the whole movement was at .an end – the International was dissolved. This precedent cannot be too sharply emphasised in face of the widespread opinion that the S.D.F.’s want of success is to be attributed to its own mistakes. Ah! what Party has not made mistakes? Marx was surely free from great tactical errors, and did he fare any better? Engels, too, discontented with the S.D.F., made, after Marx’s death, several attempts with the Avelings and others, to set on foot a new Socialist movement, and to mobilise the masses for an independent political struggle. How did he fare? Any better than the S.D.F.? No; a thousand times worse. Not only did all the organisations and movements die down after fluttering a little while, but the leaders, the Avelings, Bax, Morris and others, were forced to make their peace with the S.D.F. The difficulty of the S.D.F.’s task lay, not in that body and its methods, but in the historically created state of mind of the English working class, who were unreceptive to Socialist propaganda. Therefore it is out of place to speak of mistakes on the part of the S.D.F. Kautsky, who knows English conditions much better than most critics of the S.D.F., admits this fact, but yet is of the opinion that the S.D.F. did itself a great deal of harm by its irreconcilable criticism of the trade unions. I cannot share this opinion either. In the first place it was not the trade unions that the S.D.F. criticised, but the trade union cretinism, which at that time was so wide-spread, and of which Germany has not been free from samples. The faith in trade union action, and especially trade union diplomacy, as the one means of salvation, was the principal obstacle to the political action of the masses, and how could the S.D.F. not fight against it? In the second place, if these tactics brought the S.D.F. the enmity of the trade unions, thereby injuring the former, how was it with the I.L.P., which was much more gentle in its attitude towards trade union cretinism? Was it any more successful in winning the sympathies of the unions for itself, and for Socialism? It is true that at first Engels had great hopes of this, but the hopes were not realised. The I.L.P. remained for years quite as small a group as the S.D.F., and the unions gave it quite as little attention. Therefore the alleged bitter tone adopted by the S.D.F. towards the trade unions was not a factor in the want of success of this Party’s agitation among the masses.

(6) Theodore Rothstein, Parliamentarism and the Working Class, Justice (26th January, 1907)

Nothing could be more characteristic of the spirit which animates certain shining lights of the Labour Party than the endeavour which is to be made at the Belfast Conference to render the Parliamentary representatives of the party independent of the Conference resolutions. Those who have watched the recent developments on the Continent know that such independence is the standing demand of the opportunist sections in all Socialist parties, and constitutes but the first step in the gradual betrayal of the working class. Under the pretext that a Member of Parliament is, in the first instance, responsible to his constituents—a pretext which, as shown in last week’s “Justice,” is as disingenuous as it is baseless, since the constituents, by returning a given candidate, thereby express their solidarity with his programme and his party—gentlemen of a certain type, who regard themselves as superior to the masses, who, as Engels once said of the Fabians, “cannot possibly make themselves believe that the crude proletariat could ever accomplish by itself the gigantic task of self-emancipation,” but who in their heart of hearts merely regard the working class as a footstool for their personal ambitions—these gentlemen regard it as an intolerable tyranny that their hands should be tied by general guiding principles laid down at party conferences, and demand, in the name of individual. liberty and political expediency, freedom for their action and independence for their decisions. The result is invariably the same—alliances with the Liberal and Radical parties, betrayal of the interests of the working class, and, for some, perhaps, a seat in the Ministry or a snug administrative post.

There is, however, apart from personal ambition, usually something else in this clamour for Parliamentary independence—it is the other opportunist trait, the exaggeration of the importance of Parliamentary work. Th gentlemen do not believe in class-war tactics. They do not believe that here is an irreconcilable antagonism of interests between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat—an antagonism which it is the supreme duty of the leaders to make as patent as possible in order that the proletariat may organise itself for the complete political and economic dispossession of the bourgeoisie. They do not, therefore, regard Parliament as a means to revolutionise the minds, and to organise the forces of the proletariat, and believe, when we criticise their “statesmanlike” conduct in Parliament, and demand that they should aim, first and foremost, at the exposure of the hollow hypocrisy of the capitalist parties, that we wish them to discard all practical work, and to launch out in a campaign of abuse and strong phrases. What they see in Parliament is a nice comfortable place where, by means of clever diplomatic bargaining, and judicious, “temperate” speeches, you can obtain little favours for the working class without passing as a rude fellow or crude thinker, and without forfeiting the friendly pat on the shoulder and the invitation to a friendly cup of tea on the terrace from a “distinguished” statesman or man of business. Naturally they find that the party congresses cannot lay down rules of conduct for them, and they themselves must be left to manipulate the little ways and means which Parliamentary practice may offer them for achieving this or that “useful” object. As a result, we have again a bourgeois quagmire which sucks the gentlemen in, and renders them perfectly useless, if not positively pernicious, to the Labour movement.

But, of course, ours is a “legalist” mind. We are disposed “to the hopeless task of trying to bind the social and political progress with our red-tape formulae,” and we are blind “to the living processes of social evolution and political growth.” It is remarkable, however, that our view of what is the duty of representatives of Labour in Parliament should be supported by men who, without sharing any of our “formulae,” are, or were, nevertheless, genuine friends of the working class, possessing the additional advantage of themselves belonging to the bourgeoisie. Here is, for instance, what Mr. Frederic Harrison, at the time in the forefront of the movement for the legalisation of the trade unions and for independent political action of the working class, said in the course of an address on “The political function of the working class,” delivered before the London Trades Council, in March, 1868

“What a familiar picture to us this life in the House of Commons’. A question of great public interest has been talked over for years and years, and everyone knows perfectly what should be done. At last some judicious aspirant embodies it in a judicious little Bill, just timidly nibbling at the question, and hedging it round with all sorts of qualifications. And then he goes round to several judicious persons in the House, one of whom tells him that the ‘House’ will be afraid of this clause, and another, that this clause is unprecedented, and then that this other clause is rather too sweeping. So the poor Bill gets docked and twisted and pulled about, and all the little life in it is squeezed out; and then some very judicious speeches are made pro and con, and everybody declares it is a most important question, and ought to be considered, and a great deal of clever talking at each other goes on, the whole subject being utterly ignored all the while; and then it goes into committee, and more talking and paring and compromising goes on upon the clauses; and then the lawyers or the publicans, or some other meritorious class, discover that their interests are prejudiced by the Bill, and that they shall oppose it to the death. So the members are caught in the lobby and warned that if they vote for the Bill they will lose the lawyer or publican interest at their next election, and then somebody succeeds in getting the House counted out, and the Minister of the day, in sweet, constraining phrases, suggests that this important subject should be referred to a Select Committee upstairs; and then upstairs they go, and ten times more lobbying, and paring, and compromising, and (talking goes on than ever went on below, and the lawyers and the publicans are quite menacing, and hang about the galleries like savage dogs, and the poor legislators get very much harassed by the London season and the constant goading of the lawyers’ and the publicans, and then it gets very hot and uncomfortable in town, and someone whispers into the ear of the promoter of the Bill that he will be thought ‘impracticable’ in the House if he goes on, and ‘impracticable’ is an awful word, enough to damn any man in the House of Commons; and then members get up and ‘implore’ the hon. member to withdraw his Bill at this late period of the session; so at length the poor little Bill, all mutilated and mangled about, is withdrawn and the hon. member goes off to shoot on the moors, quite proud of having been so judicious, and of having shown so much business-like capacity …. Now they call that legislation, and that is Parliamentary government. Do you think that you or any real representatives of yours are ever likely to be adepts of that art? Do you think you or they can ‘catch the tone’ of the House, and be true to yourselves still? Is that the kind of legislation—is that the type of government which satisfies you? Truly; I think, you do not so much need to ‘catch the tone of the House’ as to utterly transform it.”

I do not apologise for the length of the extract, because for its faithful portrayal of bourgeois parliamentarism this statement is simply a chef d’oeuvre. Yet after a lapse of forty years Labour leaders of a Labour party, not merely bourgeois well-wishers, not only do their utmost to “catch the tone of the House,” but actually ask the ‘permission a those who sent them there to give them every opportunity for becoming “adepts of that art” of legislation! Verily, a fall that cannot but evoke the wrath of that old champion of the trade unions. We know that the Parliamentary representatives of the old trade unions did not take to heart the warnings of Mr. Frederic Harrison. Unlike the bourgeois Radicals of the generation of Cobbett, of Fielden, and of Daniel O’Connell, and unlike the Irish Nationalists of their own day, they did not go to Parliament to transform its tone, and to make it the public battleground for fighting out the issue between the ruling class and the class which had sent them there. They went there, and adopted the “judicious” turn of mind which their enemies wanted them to adopt, and they soon became horrified at everything “impracticable,” with the result that ultimately even the trade union weapon was knocked out of the hands of the proletariat. Let us hope that this time the organised working class will not allow its representatives to play fast and loose with their interests, as those representatives did in the past. Mach as we criticise the tactics of the Labour Party, we nevertheless acknowledge the great importance of its formation, and we shall be the first to deplore its disintegration, which is sure to follow if the ambitions of certain of its leaders find support at the Conference.

(7) Theodore Rothstein, The Russian Duma and Liberal Treachery, Justice (20th April, 1907)

We do not profess to know, nor could, we think, even those on the spot tell, what would happen if the Duma were suddenly dissolved. One thing, however, is tolerably clear. If the Duma is still tolerated by the Stolypin Government it is through no fear of a national rising. It may be right or may be mistaken. The course of the Russian revolution has taught us to be careful about our predictions, and more than once the unexpected has come to pass. But if the Stolypin Government does not disperse the second Duma as it did the first, it is solely due to financial considerations—that is, to the fear that without the sanction of some sort of national representation no more money will be obtained from abroad. The position at the same time is such that without an immediate loan of some £30,000,000 or £40,000,000, even the current liabilities cannot be met, while the Budget of the next year cannot even be contemplated without a big loan, or the very army will have to be disbanded. The position is thoroughly desperate, and, willy-nilly, the Government has to stand the Duma, hateful as it is.

That it should, under the circumstances, do so with but little grace is only unintelligible to men like the “Times” correspondent, who, for some unaccountable reason, has taken it into his head that Stolypin is a statesman, who sees the political necessity for a Russian Parliament, and that it is only due to his lack of constitutional habits of mind that he now and then indulges in antics more suited for a Turkish Pasha than for a Minister who has a Parliament to deal with. The position is much simpler. The Government regards the Duma as an insult and humiliation, and being compelled to tolerate it for a time, kicks against the pricks like a newly-broken horse. There is no idea of standing it at minute longer than is dictated by stern necessity, and when the moment of delivery from its pressure comes, it will ignominiously be driven out from the Taurida Palace like a pack of menials.

In Russian party circles this is well understood, and because it is well understood, the different parties of the Opposition pursue different tactics. Broadly speaking there are two main lines of tactics advocated and acted upon by the Social-Democrats and the Cadets (Constitutional Democrats) respectively, the remaining parties either following in the orbit of one or the other, or hesitating between the two. The former, starting from the premise that nothing but the organised pressure of the people will bring about in Russia a constitutional and parliamentary government, insist on the necessity of turning the period of comparative security, separating the Duma from the fatal moment when it will have to take a final decision on the Budget, to the greatest possible account by using every opportunity for demonstrating to the nation the nature of the autocracy, and for creating an active system of co-operation between the people and the Duma, so that the former may both become organised, and feel its vital connection with the work and fate of its representatives. With this end in view, they proposed, when Stolypin announced his intention to lay before the Duma the programme of the Government, to have a thorough discussion on the subject so as to show the people what autocracy means. Later on, when the question of famine relief came up for consideration, they advocated the establishment of local relief committees elected by the people for the administration of the relief funds, under the supervision of emissaries of the Duma, in order that the Duma may come into direct contact with the people, and that the latter may become closely attached to its deputies. Similarly, when the Government demanded the other day the suspension of four Socialist deputies on the plea that they were being prosecuted for revolutionary propaganda, the Social-Democrats demanded that the Duma should consider the subject in plenary sitting, so as to afford the people an insight into the police methods of the Government. These are but few examples among innumerable others, but they suffice to show what the Social-Democratic tactics aim at. The Duma is regarded by them as an instrument for the further development of the revolution, and their action is mainly dictated by the consideration of the effect it may have on the nation outside.

Quite different are the Cadet tactics. The Cadets do not believe in the possibility of the resurrection of the revolution; neither do they desire it; and having thus only the good grace of the Government to fall back upon for the preservation of what small modicum of national representation: has been obtained, they aim mainly at winning it. Formerly it was different. During the first Duma, the Cadets, though also sceptical about the powers of the revolution, still believed that by Parliamentary means they could overcome the autocracy, and compel it to yield to the demands of the national representatives, and, in particular, to grant responsible government. Later events have shown their mistake, and now, though they still indulge from time to time in optimistic prophecies, they have come to the conclusion that far from gaining additional powers the Duma will have to be thankful if it is allowed to exist at all, even as it is. Hence they not only endeavour to avoid everything which may bring about a conflict with the Government, but actually try to win its favour by being as submissive as possible. To the Government declaration of policy they have replied by silence; to the Social-Democratic proposal to establish local famine relief committees they replied that a parliament can only control, but not act; and the demand of the Government to suspend the incriminated Socialist deputies they referred to a committee, in order to examine it there in all secrecy. Their speeches are, if possible, still more conciliatory than their acts. When the subject of the field courts-martial came up for discussion, their strongest condemnation of them was from a legal point of view, and when the Duma began the debate on the Budget, the Cadet speakers confined themselves to technical points. In both cases it was the Social-Democrats who placed the debates on, the proper political level, and the speeches delivered on this occasion by comrades Alexinsky and Tseretelli belong to the best political and oratorical efforts of the present Duma, and do credit to the International Socialist movement.

It is easy to see which of the two tactics is right. As a matter of fact, the Cadets themselves perceive that they are slowly but surely being dragged into the mire of opportunism in which they will suffocate. Their only argument, or rather apology, is: What else is there to hope for but the favour of the Government? So at least their case was frankly stated the other day by M. Miliukoff, their foremost leader. It shows how utterly senile Russian Liberalism is, in spite of the brief period of its existence, how distrustful of the powers of the people, how impotent for any energetic action.

That the Government would be such fools as not to avail themselves of this Cadet “psychology,” could not be expected, even by its bitterest detractors. The threat of dissolution, like the sword of Damocles, is kept hanging over the Duma with the special purpose of frightening the Cadets into submission, and every day brings the news of fresh acts of Ministerial arbitrariness, intended to bully the Duma, and particularly the Cadets, and make them obedient and humble. Like the boy in the wood crying “Wolf, wolf!” M. Stolypin has already a little overdone these tactics, and not only the Extreme Left, but even the foreign press correspondents are beginning to recover their senses, and perceive the emptiness of the threats. But on the Cadets they are still having a marvellous effect. They have become so thoroughly paralysed with fright that the only cry they can utter is one for mercy. “Don’t discredit us too much,” was, in substance, the bitter cry of M. Roditcheff to Stolypin the other day; “we will do everything for you, forget everything, only spare us a little in the eyes of the nation.”

The thing would be comical if it were not so serious. Thanks to the submissiveness of the Cadets, the Government is building up a majority for the Budget, and will thus gain the object for the sake of which it is still keeping up the show of a national representation. One might have thought that precisely the Budget would have been made by the Cadets the ground on which to give the Government battle royal. For one thing it is pre-eminently a parliamentary ground. Then the Government itself, in an unguarded moment of frankness, declared that it attached the greatest value to the sanction of the Budget by the Duma. Lastly, the Cadets know it as well as anybody else, that with the passing of the Budget not only will the existence of the Duma be a mere matter of days, if not hours, but the Government will he armed with new means to continue the war against the nation. Yet, so thoroughly have the Cadets lost their wits that they have actually, and in the teeth of the solemn declarations made but a few weeks ago, declared in advance that they will pass the Budget! It should he noted that the law does not allow the Duma any scope for altering the estimates to any appreciable extent. One part of the Budget is exempted from its competency by the so-called Fundamental Laws which the Duma cannot even touch without infringing the prerogatives of the Czar. The other part is exempted by virtue of a law which cannot be altered except by a special legislative act, while the remaining portion of the Budget consists of the expenditure in connection with the railways, State liquor traffic, and other similar undertakings, which represent going concerns, and cannot be either liquidated or appreciably tampered with at the present moment.. It would thus seem that the even apart from everything else, might have made at least the extension of the budgetary rights of the Duma the condition for passing the Budget. But they refuse to do even that, and for fear of raising a conflict which may bring about a dissolution, they are prepared to sell even the primordial rights of Parliament, which they value so highly.

It is, indeed, impossible to be indignant with them; they are too contemptible as men and as politicians. Nevertheless, their treachery will cost Russia new torrents of blood, in which, let us hope, not only the autocracy but they themselves will ultimately be drowned. The Russian Government may, with their aid, yet obtain a new lease of life for some short period, but the catastrophe will come all the same. The financial situation is too hopeless to be patched up even by a series of loans, while at the same time ever wider and wider circles of the population are being. drawn into the stream of the revolution. The eruption of 1905 proved inadequate to throw down the autocratic edifice which stood for centuries; but it has released new forces, and opened new channels, and now the work of the revolution is again proceeding underground till a new eruption will complete what the first began.

(8) Theodore Rothstein, The Power of the Russian Revolution, The New York Call (17th July, 1919)

July 20th and 21st 1919 will go down in the annals of history as a red-letter day of the highest significance. On these dates for the first time since the beginning of the modern labour movement, the international working class has discovered and proclaimed to the world its moral unity. It is no longer the formal and mechanical unity of former days when the advance guards, the Socialists, turned out into the streets to perform the rite of simultaneous processions and meetings with no more thought of the ideal purpose underlying the actions and no deeper consciousness of the motives which inspired it than usually go with the performance of rites. On these historical days it is the masses themselves, moved by the same thought and the same emotions, who will throughout the world proclaim their solidarity with the one and the same cause now clothed with flesh and blood, and merge their individual identity in the moral ones of the class of which they have hitherto been disjointed members. In short the two days, July 29th and 21st will mark the constitution of the international working class hitherto more a concept than a reality, as a living entity, almost an organism with a common sensitiveness and common consciousness. The dream, the expectation, the scientific prognosis of the great founders of modern Socialism, so long delayed, but all the while imperceptibly maturing in the womb of Time, has, with startling suddenness, on the morrow of an unparalleled period of mutual massacre and hate, become a vivid and vivifying reality. There is an international working class, there is a proletariat, the grave digger of the past, the builder of the future.

This miracle has been accomplished by the genius and daring of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution which has now, for more than eighteen months, been transforming the world of ideas, the world of action, in a way never paralleled by any event, by any movement in previous history. Who but a Goethe felt the immediate effect of the great French Revolution at the battle of Valmy in 1792, that is, three years after its beginning? And was any contemporary in the least conscious of the effect of the teaching - we shall not say of semi-mythical Jesus and his insignificant handful of followers - but of St Paul the real founder of Christianity as a world religion? Yet here, less than two years after the accomplishment of a revolution in a far distant and almost unknown country, in spite of the immense amount of force of counter-influences, in spite of an almost impenetrable material and moral blockade erected by its enemies, in spite of an almost opaque atmosphere of poisonous gases, created by the lies calumnies and distortions of these same enemies - in spite of all this, the whole world of Labour is already feeling and responding to its stimulus, so that even in its most backward sections, those of this country can longer restrain their emotions, and have decided to come out into the streets to demonstrate them? If, verily, it seems as if Time had long been pregnant with the new ideas, and had only been waiting for the bold Caesarean stroke of the revolutionary lancet to give birth to them.

The Bolsheviks of Russia, under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, have, by the courage of their act performed the necessary operation, and every day that passes and brings with it the continuation of their rule sees the further and wider penetration of the revolutionary proletarian ideas which are inscribed on their glorious banner. And within every such new day we feel that their rule is going to continue and to gather strength inside and outside, all the efforts of the enemy, internal and external, notwithstanding. The artificial famine created in Russia by the Allies and their Tsarist clients by their blockade and occupation and devastation of the corn-bearing and mining districts, the constant and abundant supply of tanks, guns aeroplanes, poison gases and other diabolical engines of destruction to the Koltchaks and Denikins, the spread of false news and the suppression of true news, zealously practised by the enemies of Bolshevism - all these and numerous other means employed by the capitalist world to strangle the great proletarian revolution of Russia seem to be powerless to achieve anything but the consolidation and the ever-spreading popularity of the Soviet régime. In fact, they merely help to convince the labouring masses, both inside and outside Russia that the Soviet régime is firmly rooted in the consciousness of the people, and, conversely, that the salvation of the latter, both inside and outside Russia, after the unparalleled capitalist barbarity of the war and the perfidy of the peace, lies in the maintenance and universal adoption of the Soviet régime, the régime of the working class in power. And it is because of this growing and ever-spreading two-fold consciousness that the proletariat of the world will, on July 20th and 21st, turn out into the streets and loudly proclaim: “Down with the capitalist and Imperialist intervention! Long live the Soviet Republic”!

(9) Theodore Rothstein, The Fate of the German Revolution, The New York Call (27th November 1919)