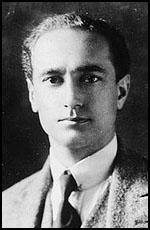

Paul Dukes

Paul Dukes, the son of Edwin Joshua Dukes, a Congregational minister, and his wife, Edith Mary Pope, was born on 10th February 1889 at North Field, Bridgwater. Dukes was educated at Caterham School before travelling to St Petersburg to study music. He found work at the Mariinsky Theatre with the conductor Albert Coates.

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War he became a member of the Anglo-Russian Commission, a British propaganda organisation. According to his biographer, Michael Hughes: "For the next two years he was involved in promoting the somewhat nebulous range of propaganda activities carried out by the commission, serving both in the Russian capital and at the Foreign Office in London." In the summer of 1917 he was asked by the Tsarist Secret Police to spy on the Bolshevik leaders. Michael Smith, the author of Six: A History of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (2010), argues: "In order to spell out to officials back in Whitehall precisely what the Russians did and did not know, Dukes filed two heavyweight reports on the leading Bolsheviks, derived from information provided by the Russians and the French." Dukes also sent regular dispatches about events in Russia to the Foreign Office. Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013) has pointed out: "Dukes... had witnessed first-hand the revolution that had swept the Bolsheviks to power. Indeed he had been one of the trio of Englishmen who had first glimpsed Lenin on his return to Petrograd in 1917. He had also seen the civil unrest that accompanied Lenin's first months in government. Dukes's intense eyes hinted at an inner sharpness, an ability to think on his feet and take clear decisions in moments of crisis. This natural intelligence, coupled with his fluency in the language, had already earned him unofficial employment in the service of the Foreign Office. It was almost certainly his vivid despatches about the Bolshevik revolution that brought him to the attention of Mansfield Cumming."

In the summer of 1918 Dukes was recalled to London for a meeting with Colonel Frederick Browning. In his book, Red Dusk and the Morrow: Adventures and Investigations in Soviet Russia (1922) Dukes reported that Browning explained: "You doubtless wonder that no explanation has been given to you as to why you should return to England. Well, I have to inform you, confidentially, that it has been proposed to offer you a somewhat responsible post in the Secret Intelligence Service. We have reason to believe that Russia will not long continue to be open to foreigners. We wish someone to remain there to keep us informed of the march of events."

Dukes was then taken to see Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6. "This extraordinary man was short of stature, thick-set with grey hair half covering a well-rounded head. His mouth was stern and an eagle eye, full of vivacity, glanced - or glared as the case may be - piercingly through a gold-rimmed monocle. At first encounter, he appeared very severe. His manner of speech was abrupt. Yet the stern countenance could melt into the kindliest of smiles, and the softened eyes and lips revealed a heart that was big and generous."

Smith-Cumming's idea was for Dukes to rebuild MI6's shattered network inside Russia. He was to travel alone and would be expected to create his own network of couriers to smuggle out his reports. Smith-Cumming told him: "Don't go and get killed" Turning to Colonel Frederick Browning Smith-Cumming said: "You will put him through the ciphers and take him to the laboratory to learn the inks and all that."

Three weeks later Dukes was in Petrograd, using a false identity as a Ukrainian member of the Cheka. He joined up with other British secret agents that included John Scale and Stephen Alley. Dukes spoke fluent Russian and was able to pass himself off as a member of the secret police. He also joined the Bolshevik Party. His biographer, Michael Hughes claims that: "Dukes showed himself to be a master of disguises during his time in Russia, frequently changing his appearance and using more than a dozen names to conceal his identity."

In his autobiography, Red Dusk and the Morrow: Adventures and Investigations in Soviet Russia, Dukes recalled his work as a spy: "I wrote mostly at night, in minute handwriting on tracing-paper, with a small caoutchouc (latex bag) about four inches in length, weighted with lead, ready at my side. In case of alarm, all my papers could be slipped into this bag and within thirty seconds be transferred to the bottom of a tub of washing or the cistern of a water closet. In efforts to discover arms or incriminating documents, I have seen pictures, carpets, and bookshelves removed and everything turned topsy-turvy by diligent searchers, but it never occurred to anybody to search through a pail of washing or thrust his hand into the water-closet cistern. Only on one occasion was I obliged to destroy documents of value, while of the couriers who, at grave risk, carried communications back and forth from Finland, only two failed to arrive and l presume were caught and shot."

Dukes returned to London where he was awarded the KBE by King George V, since he was not, as a civilian, eligible to receive the Victoria Cross. Despite the success of his activities in Russia the Secret Intelligence Service appeared unwilling to make further use of him and so he moved to the United States where he joined a tantric community at Nyack, 15 miles from New York City.

On his return to England he became a special correspondent of The Times. He was also chairman of British Continental Press from 1930 to 1937. Just before the outbreak of the Second World War he was asked by some acquaintances to visit Germany in order to trace the whereabouts of a wealthy Czech businessman who was in hiding in Nazi Germany. He wrote about this in his book, An Epic of the Gestapo (1940). During the war he lectured on behalf of the Ministry of Information.

Dukes developed a strong interest in yoga and was the author of Yoga for the Western World (1955) and The Yoga of Health, Youth and Joy (1960). He also made a series of broadcasts for the BBC on the subject.

Sir Paul Dukes died in Cape Town, South Africa, on 27th August 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) Michael Smith, Six: A History of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (2010)

Paul Dukes, a fluent Russian speaker, had already been in contact with the intelligence services while working in Petrograd as a member of the Anglo-Russian Commission, a British propaganda organisation. A few months before the October Revolution, he was asked by Tsarist intelligence chiefs to provide them with as much information as possible on the Bolshevik leaders. In order to spell out to officials back in Whitehall precisely what the Russians did and did not know, Dukes filed two heavyweight reports on the leading Bolsheviks, derived from information provided by the Russians and the French. These added significantly to what MI1c and MI5 knew and almost certainly had an impact on Cumming's subsequent decision to select him for the secret service mission in Russia. After the revolution, Dukes remained in Russia, working in the south, ostensibly with a relief mission funded by the American YMCA. Called back to England in the summer of 1918 by an "urgent" telegram from the Foreign Office, Dukes arrived by Royal Navy destroyer at Aberdeen and was put on a train to London's King's Cross station where a car was waiting to pick him up....

The colonel, Frederick Browning, took Dukes to Cumming's office to meet the chief. "From the threshold the room seemed bathed in semi-obscurity," Dukes recalled. "The writing desk was so placed with the window behind it that on entering everything appeared only in silhouette. A row of half-a-dozen extending telephones stood at the left of a big desk littered with papers. On a side-table were maps and drawings, with models of aeroplanes, submarines, and mechanical devices, while a row of bottles of various colours and a distilling outfit with a rack of test tubes bore witness to chemical experiments and operations."

These evidences of scientific investigation only served to intensify an already overpowering atmosphere of strangeness and mystery. But it was not these things that engaged my attention as I stood nervously waiting. My eyes fixed themselves on the figure at the writing table. In the capacious swing desk-chair, his shoulders hunched, with his head supported on his hand, sat the Chief. This extraordinary man was short of stature, thick-set with grey hair half covering a well-rounded head. His mouth was stern and an eagle eye, full of vivacity, glanced - or glared as the case may be - piercingly through a gold-rimmed monocle. At first encounter, he appeared very severe. His manner of speech was abrupt. Yet the stern countenance could melt into the kindliest of smiles, and the softened eyes and lips revealed a heart that was big and generous. Awe-inspired as I was by my first encounter, I soon learned to regard "the Chief" with feelings of the deepest personal admiration. In silhouette, I saw myself motioned to a chair. The Chief wrote for a moment and then suddenly turned with the unexpected remark, "So I understand you want to go back to Soviet Russia, do you?" As if it had been my own suggestion.''

Dukes was given the designation ST25, as he was to be run by John Scale in Stockholm. Cumming told him that he had to find Merrett and pick up the reins of the agent networks set up in Petrograd and Moscow by Stephen Alley, Ernest Boyce, Scale and Jim Gillespie, as well as those run by the now-dead naval attache Francis Cromie. "The words Archangel, Stockholm, Riga, Helsingfors recurred frequently, and the names were mentioned of English people in all those places and in Petrograd," Dukes recalled. "It was finally decided that I alone should determine how and by what route I should regain access to Russia, and how I should dispatch reports. "Don't go and get yourself killed," said the Chief in conclusion, smiling. Three weeks later, I set out for Russia, into the unknown."

(2) Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013)

Sidney Reilly and George Hill were not heading back to Russia alone: Cumming had recently hired a new recruit to his organisation, someone he had first met four months previously. His name was Paul Dukes and he was charged with the task of rebuilding Cumming's shattered network inside Russia.

Dukes was a talented musician and former conductor with the Imperial Mariinsky Opera. He had been living in Russia since 1908 and had witnessed first-hand the revolution that had swept the Bolsheviks to power. Indeed he had been one of the trio of Englishmen who had first glimpsed Lenin on his return to Petrograd in 1917. He had also seen the civil unrest that accompanied Lenin's first months in government.

Dukes's intense eyes hinted at an inner sharpness, an ability to think on his feet and take clear decisions in moments of crisis. This natural intelligence, coupled with his fluency in the language, had already earned him unofficial employment in the service of the Foreign Office. It was almost certainly his vivid despatches about the Bolshevik revolution that brought him to the attention of Mansfield Cumming.

"One day, when in Moscow," wrote Dukes, "I was handed an unexpected telegram. 'Urgent' - from the British Foreign Office. 'You are wanted at once in London', it ran."

He wasted no time in heeding the call. He took the train to Norway, bought himself passage across the North Sea and eventually arrived in Aberdeen. Here, he was met by a passport control officer who put him on the first train to London where a car was awaiting him.

Dukes was mystified by the summons. "Knowing neither my destination, nor the cause of my recall, I was driven to a building in a side street in the vicinity of Trafalgar Square. "This way," said the chauffeur, leaving the car."

Dukes was led into a labyrinthine building with "rabbit-burrow-like passages, corridors, nooks and alcoves, piled higgledy-piggledy on the roof." He was eventually ushered into a tiny room, the office of a colonel in uniform.

Dukes was not at liberty to provide his name when he came to publish his account, but it may well have been Colonel Freddie Browning, who was still employed as Cumming's unofficial deputy.

After a warm handshake, the colonel informed Dukes that he was being offered a job in the Secret Intelligence Service. He was to return to Russia and remain there, "to keep us informed of the march of events."

Dukes was taken aback by the unexpected job offer and blurted a series of objections. The colonel brushed these aside with a wave of his hand and told him to return to Whitehall Court on the following day. The arrival of a young secretary heralded the end of the interview: a bewildered Dukes was led back through the maze of passages.

"Burning with curiosity and fascinated already by the mysticism of this elevated labyrinth, I ventured a query to my young female guide. "What sort of an establishment is this?" I said.Dukes noticed a twinkle in her eye. "She shrugged her shoulders and without replying pressed the button for the elevator. "Good afternoon," was all she said as I passed in."

Dukes's induction into the Secret Intelligence Service was to become a great deal more mysterious on the following day. He was escorted back to the colonel's office and provided with a more precise brief. He was to gather intelligence on Bolshevik policy and was also to investigate the level of popular support for Lenin's regime.

"As to the means whereby you gain access to the country," said the colonel, "under what cover you will live there, and how you will send out reports, we shall leave it to you ... to make suggestions."

"In silhouette I saw myself motioned to a chair. The Chief wrote for a moment then suddenly turned with the unexpected remark, 'So, I understand you want to go back to Soviet Russia, do you?' as if it had been my own suggestion."

(3) Paul Dukes, Red Dusk and the Morrow: Adventures and Investigations in Soviet Russia (1922)

Knowing neither my destination nor the cause of my recall, I was driven to a building in a side-street in the vicinity of Trafalgar Square. The chauffeur had a face like a mask. We entered the building and the elevator whisked us to the top floor, above which additional superstructures had been built for war-emergency offices. I had always associated rabbit warrens with subterranean abodes. But here in this building, I discovered a maze of burrow-like passages, corridors, nooks and alcoves, piled higgledy-piggledy on the roof. Crossing a short iron bridge, we entered another maze, until just as I was beginning to feel dizzy I was shown into a tiny room about ten-toot-square where sat an officer in the uniform of a British Army colonel. "Good afternoon, Mr Dukes," said the colonel. "You doubtless wonder that no explanation has been given to you as to why you should return to England. Well, I have to inform you, confidentially, that it has been proposed to offer you a somewhat responsible post in the Secret Intelligence Service. We have reason to believe that Russia will not long continue to be open to foreigners. We wish someone to remain there to keep us informed of the march of events."

(4) Paul Dukes, Red Dusk and the Morrow: Adventures and Investigations in Soviet Russia (1922)

I wrote mostly at night, in minute handwriting on tracing-paper, with a small caoutchouc (latex bag) about four inches in length, weighted with lead, ready at my side. In case of alarm, all my papers could be slipped into this bag and within thirty seconds be transferred to the bottom of a tub of washing or the cistern of a water closet. In efforts to discover arms or incriminating documents, I have seen pictures, carpets, and bookshelves removed and everything turned topsy-turvy by diligent searchers, but it never occurred to anybody to search through a pail of washing or thrust his hand into the water-closet cistern. Only on one occasion was I obliged to destroy documents of value, while of the couriers who, at grave risk, carried communications back and forth from Finland, only two failed to arrive and l presume were caught and shot.