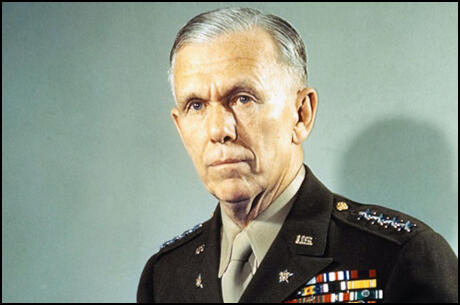

George Marshall

George Marshall was born in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, on 31st December, 1880. He graduated from Virginia Military Institute in 1901. The following year he received a commission as a second lieutenant and was sent to the Philippines.

In 1906 Marshall resumed his education at Fort Leavenworth. He graduated top of the class and qualified for the Army Staff College. When he completed the course he was kept on for another two years as an instructor.

In the First World War Marshall served on the Western Front and was involved in the planning of the Meuse-Argonne offensive in 1918. Promoted to colonel Marshall served for five years as aide to General John Pershing (1919-24) and had a spell of duty in China (1924-27). This was followed by five years as an instructor at Fort Benning (1927-33).

In June 1933 Marshall was given command of the 8th Infantry and became responsible for 34 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in Georgia, Florida and South Carolina. Marshall was a strong believer in the CCC and argued that the US Army should fully support this social experiment.

Marshall was promoted to brigadier general in October, 1936, and was given command of the 5th Brigade at Vancouver Barracks in Washington. He was responsible for the CCC camps in the district. Soon afterwards he became seriously ill and had to have his thyroid gland removed. For a while it was believed that Marshall would have to be retired from the army but he eventually made a full recovery.

In August 1938, Marshall was appointed chief of the War Plans Division and three months later he became deputy Chief of Staff. This brought Marshall into contact with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and members of his administration. Harry Hopkins was especially impressed with Marshall and suggested to the president that he should become the new Chief of Staff. Roosevelt agreed and he assumed office in September 1939.

Marshall directed the United States armed forces throughout the Second World War. Over the next four years the US Army grew to a force of 8,300,000 men. Unlike his predecessor, Marshall was a strong advocate of air power and therefore got on well with General Henry Arnold. However he clashed with Admiral Ernest King over his policy of using all available resources to defeat Germany before Japan. As a result some critics have claimed that his actions prolonged the Pacific War.

In 1944 Marshall was disappointed not to have been given command of the Allied D-Day landings. However, Franklin D. Roosevelt argued that he could not afford to lose him as Chief of Staff. He was involved in the planning of the invasion and Winston Churchill later claimed that Marshall's achievements were monumental and described him as the "organizer of victory".

Marshall was given the rank of a five-star general in December 1944. Along with William Leahy he was senior to Ernest King, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur and Henry Arnold. Marshall resigned as Chief of Staff on 21st November, 1945, but a few days later Harry S. Truman persuaded him to become U.S. ambassador in China.

In January 1947, Truman, who called Marshall "the greatest living American", appointed him as his Secretary of State. While in this position, Marshall devised the European Recovery Program (ERP). Over the first year the ERP spent $5,300,000,000 and played a decisive role in the reconstruction of war-torn Europe.

In 1949, ill-health forced Marshall to resign from office and he was replaced by Dean Acheson. However, the following year, aged sixty-nine, Marshall accepted the post as Secretary of Defence and helped organize United States forces in the early stages of the Korean War.

In the summer of 1951 Marshall was attacked by Joe McCarthy, the right-wing senator from Wisconsin, as being soft on communism. In a speech that McCarthy gave on 14th June, he accused the Secretary of Defence of making decisions that "aided the Communist drive for world domination" and implied that he was a traitor to his country.

Disillusioned by the smear campaign, Marshall retired from politics. However, Marshall's talents were appreciated abroad and in 1953 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace for his contribution to the recovery of Europe after the Second World War. George Marshall died in Washington on 16th October, 1959.

Primary Sources

(1) James F. Byrnes, Speaking Frankly (1947)

In August 1940, General Marshall appeared before the Senate Appropriations Committee to testify on a defense appropriation bill. During a recess, he told me that his greatest difficulty was his inability to promote younger officers of unusual ability. Possession of such authority, he said, was essential to the proper reorganization of the Army. He told me he had requested Chairman May, of the House Military Affairs Committee, to introduce the necessary legislation some months before but had been unable to get action on it.

His needs were so impressive that I requested him to have one of his technicians draft an amendment that would accomplish the purpose he desired and stated I would try to help him. Under the rules of the

Senate, the amendment could not be added to an appropriation bill in committee but when the bill was reported to the floor, I offered an amendment, adopted without objection, providing that "In time of war

or national emergency determined by the President, any officer of the Regular Army may be appointed to higher temporary grade without vacating his permanent appointment."

When we met in conference with the members of the House Appropriations Committee, I explained the urgency of the proposal and they accepted it. On September 9 it became law and under its provisions the War Department began the task of promoting over the heads of officers of high rank the younger officers who thereafter led our armies to victory. Before the end of the year, 4,088 of these promotions were made. Among the officers advanced were men like General Eisenhower, General George C. Kenney, General Carl A. Spaatz, General Mark Clark and the late General George S. Patton. Elsenhower was promoted over 366 senior officers.

(2) General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe (1948)

Washington in wartime has been variously described in numbers of pungent epigrams, all signifying chaos. Traditionally the government, including the service departments, has always been as unprepared for war and its all-embracing problems as the country itself; and the incidence of emergency has, under an awakened sense of overwhelming responsibility, resulted in confusion, intensified by a swarming influx of contract seekers and well-meaning volunteers. This time, however, the War Department had achieved a gratifying level of efficiency before the outbreak of war. So far as my own observations during the months I served there would justify a judgment, this was due to the vision and determination of one man, General Marshall. Naturally he had support. He was backed up by the President and by many of our ablest leaders in Congress and in key positions in the Administration. But it would have been easy for General Marshall, during 1940-41, to drift along with the current, to let things slide in anticipation of a normal end to a brilliant military career - for he had earned, throughout the professional Army, a reputation for brilliance. Instead he had for many months deliberately followed the hard way, determined that at whatever cost to himself or to anyone else the Army should be decently prepared for the conflict which he daily, almost hourly, expected.

(3) William Leahy, chief of staff to the commander in chief of the United States, wrote about George Marshall in his autobiography, I Was There (1950)

Regular meetings of the Joint Chiefs took place on Wednesdays, beginning with luncheon. Special sessions were held at any time, often on Sundays or even late at night. No one other than the Chiefs of Staff was present at the meetings, except that when an important theatre commander was in Washington he would usually be asked to discuss with us the situation and problems in his area. From time to time representatives of our allies - China, Australia, the Netherlands and the exiled Poles, for example-would ask to be allowed to present their case to the Joint Chiefs. On occasions, these requests were granted.

Throughout the war, the four of us - Marshall, King, Arnold, and myself - worked in the closest possible harmony. In the post-war period, General Marshall and I disagreed sharply on some aspects of our foreign political policy. However, as a soldier, he was in my opinion one of the best, and his drive, courage, and imagination transformed America's great citizen army into the most magnificent fighting force ever assembled.

In numbers of men and logistic requirements, his army operations were by far the largest. This meant that more time of the Joint Chiefs was spent on his problems than on any others - and he invariably presented them with skill and clarity.

(4) General Alan Brooke, Chief of Imperial General Staff (diary entry, 15th June, 1944)

After lunch again the American COS, this time to discuss Burma. It is quite clear in listening to Marshall's arguments and questions that he has not even now grasped the true aspect of the Burma Campaign! After the meeting I approached him about the present Stilwell set up, suggesting that it was quite impossible for him to continue filling 3 jobs at the same time, necessitating him being in 3 different locations, namely: Deputy Supreme Commander, Commander Chinese Corps, and Chief of Staff to Chiang Kai-shek! Marshall flared up and said that Stilwell was a 'fighter' and that is why he wanted him there, as we had a set of commanders who had no fighting instincts! Namely Giffard, Peirse and Somerville, all of which according to him were soft and useless etc etc. I found it quite useless arguing with him.

Marshall had originally asked us to accept this mad Stilwell set up to do him a favour, apparently as he had no one else suitable to fill the gaps. I was therefore quite justified in asking him to terminate a set up which had proved itself as quite unsound. I had certainly not expected him to flare up in the way he did and to start accusing our commanders of lack of fighting qualities, and especially as he could not have had any opportunities of judging for himself and was basing his opinions on reports he had received from Stilwell. I was so enraged by his attitude that I had to break off the conversation to save myself from rounding on him and irreparably damaging our relationship.

(5) George Marshall, Secretary of State, speech at Harvard University (5th June, 1947)

I need not tell you gentlemen that the world situation is very serious. That must be apparent to all intelligent people. I think

one difficulty is that the problem is one of such enormous complexity that the very mass of facts presented to the public by press and radio make it exceedingly difficult for the man in the street to reach a clear appraisement of the situation. Furthermore, the people of this country are distant from the troubled areas of the earth and it is hard for them to comprehend the plight and consequent reactions of the long-suffering peoples, and the effect of those reactions on their governments in connection with our efforts to promote peace in the world.

In considering the requirements for the rehabilitation of Europe, the physical loss of life, the visible destruction of cities, factories, mines, and railroads was correctly estimated; but it has become obvious during recent months that this visible destruction was probably less serious than the dislocation of the entire fabric of European economy. For the past ten years conditions have been highly abnormal. The feverish preparation for war and the more feverish maintenance of the war effort engulfed all aspects of national economies. Machinery has fallen into disrepair or is entirely obsolete. Under the arbitrary and destructive Nazi rule, virtually every possible enterprise was geared into the German war machine. Long-standing commercial ties, private institutions, banks, insurance companies, and shipping companies disappeared through loss of capital, absorption through nationalization, or by simple destruction. In many countries, confidence in the local currency has been severely shaken.

The breakdown of the business structure of Europe during the war was complete. Recovery has been seriously retarded by the fact that two years after the close of hostilities a peace settlement with Germany and Austria has not been agreed upon. But even given a more prompt solution of these difficult problems, the rehabilitation of the economic structure of Europe quite evidently will require a much longer time and greater effort than had been foreseen.

There is a phase of this matter which is both interesting and serious. The farmer has always produced the foodstuffs to exchange with the city dweller for the other necessities of life. This division of labor is the basis of modern civilization. At the present time it is threatened with breakdown. The town and city industries are not producing adequate goods to exchange with the food-producing farmer. Raw materials and fuel are in short supply. Machinery is lacking or worn out. The farmer or the peasant cannot find the goods for sale which he desires to purchase. So the sale of his farm produce for money which he cannot use seems to him an unprofitable transaction. He, therefore, has withdrawn many fields from crop cultivation and is using them for grazing. He feeds more grain to stock and finds for himself and his family an ample supply of food, however short he may be on clothing and the other ordinary gadgets of civilization.

Meanwhile people in the cities are short of food and fuel. So the governments are forced to use their foreign money and credits to procure these necessities abroad. This process exhausts funds which are urgently needed for reconstruction. Thus a very serious situation is rapidly developing which bodes no good for the world. The modern system of the division of labor upon which the exchange of products is based is in danger of breaking down.

The truth of the matter is that Europe's requirements for the next three or four years of foreign food and other essential

products - principally from America - are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial additional help or face economic, social, and political deterioration of a very grave character.

The remedy lies in breaking the vicious circle and restoring the confidence of the European people in the economic future of their own countries and of Europe as a whole. The manufacturer and the farmer throughout wide areas must be able and willing to exchange their products for currencies the continuing value of which is not open to question.

Aside from the demoralizing effect on the world at large and the possibilities of disturbances arising as a result of the desperation of the people concerned, the consequences to the economy of the United States should be apparent to all. It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working

economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.

Such assistance, I am convinced, must not be on a piecemeal basis as various crises develop. Any assistance that this government may render in the future should provide a cure rather than a mere palliative. Any government that is willing to assist in the task of recovery will find full cooperation, I am sure, on the part of the United States government. Any government which maneuvers to block the recovery of other countries cannot expect help from us. Furthermore, governments, political parties, or groups which seek to perpetuate human misery in order to profit therefrom politically or otherwise will encounter the opposition of the United States.

It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.

(6) Walter Trohan, The American Mercury (March, 1951)

George Marshall was the willing instrument of the tragic policy which held that Russia was an ally to be trusted, that Joe Stalin was "good old Joe". He was the willing instrument of the Hisses and the Achesons, the Lattimores and the Jessups, the misguided men who let American boys die to make America safe for Communism. Whenever the American people have depended on him, he has come up with advice or decisions which have led to disaster.

(7) Joseph McCarthy, speech in the Senate (14th June, 1951)

I realize full well, how unpopular it is to lay hands on the laurels of a man who has been built into a great hero. I very much dislike it, but I feel that it must be done if we are to intelligently make the proper decisions in the issues of life and death before us. If Marshall was merely stupid, the laws of probability would dictate that part of his decisions would serve America's interests.

Since Marshall resumed his place as major of the palace last September, with Acheson as captain of the palace guard and that weak, fitful, bad-tempered and usable Merovingian in their custody, the outlines of the defeat they mediate have grown plainer.

(8) Collier's Magazine, commenting on Joseph McCarthy's speech attacking George Marshall and Dean Acheson (18th August, 1951)

It is incredible that any American who is both sane and honest can believe that George Marshall or Dean Acheson is a traitorous hireling of the Kremlin.

(9) Dwight D. Eisenhower, speech in Denver (9th September, 1952)

Let me be specific. I know that charges of disloyalty have, in the past, been leveled against General George C. Marshall. I have been privileged for thirty-five years to know George Marshall personally. I know him, as a man and as a soldier, to be dedicated with singular selfishness and the profoundest patriotism to the service of America. And this episode is a sobering lesson in the way freedom must not defend itself.