Spartacus Blog

Art and the Women's Suffrage Movement

In her seminal book, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987), Lisa Tickner argues: "The women's suffrage campaign was for many years marginal to the interests of political historians, and its use of posters, postcards and large-scale public spectacle - that 'agitation by symbol' which is the subject of this book - fell victim to what John Gorman has called 'a common myopia with regard to the visual past'. Too 'artistic' for the interests of political history, it was too political (and too ephemeral) for the history of art." (1)

Lisa Tickner's book has been out of print for many years and Elizabeth Crawford did a great service to people interested historians when she published in the subject of women's suffrage when she published Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018). Crawford rightly praises Tickner's "beautifully illustrated text is supported by a most absorbing series of endnotes that demonstrate how widely the author cast her research net and how thoroughly she interrogated archival sources." Crawford admits that Tickner's book had given her the "springboard" to enable her to concentrate on "the lives of the artists themselves." (2)

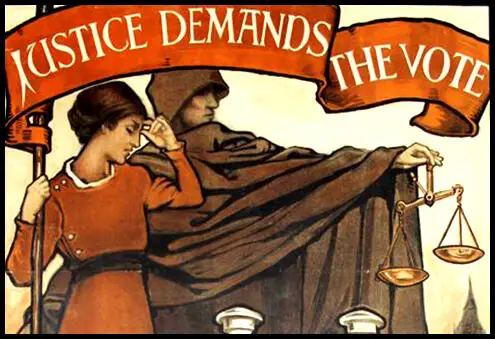

Artists' Suffrage League

The story begins when the Artists' Suffrage League was founded in January 1907 by professional women artists to help with the preparations for the first large-scale public demonstration by the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Its object was "to further the cause of Women's Enfranchisement by the work and professional help of artists... by bringing in an attractive manner before the public eye the long-continued demand for the vote." (3)

The first chairperson of the Artists' Suffrage League was Mary Lowndes, an important stained-glass and poster artist. She designed many of the banners used by the NUWSS including those for the demonstration of 21 June 1908, and for the Women's Pageant of Trades and Professions held the following year at the Albert Hall as part of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance Congress. (4)

Mary Lowndes pointed out in her treatise On Banners and Banner-Making (1909): "A banner is not a placard... a banner is a thing to float in the wind, to flicker in the breeze, to flirt its colours for your pleasure, to half show and half conceal a device you long to unravel: you do not want to read it, you want to worship it." (5)

Philippa Strachey explained in a letter to Millicent Garrett Fawcett about the importance of Lowndes to the NUWSS. "On the Committee she was most helpful about everything and was delightful to work with because she was entirely free from any sort of nonsense; she only cared about the success of the procession as a whole and was perfectly willing to subordinate her decorations and give up all her cherished ideas when difficulties cropped up. She really did an immense amount of work for us and I shudder to think of what has happened to her own trade meantime." (6)

Emily Ford

Emily Ford was appointed as vice-chairman of the Artists' Suffrage League. (7) A long-term supporter of women's suffrage Ford joined the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage in 1886. Three years later she signed the Women Householder's Declaration in favour of women's suffrage, and in 1897 was one of seventy-six painters listed as supporting the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. During this period she painted the portrait of Josephine Butler, that is now in the Leeds Art Gallery. (8) Ford was also the vice-president of the Leeds Suffrage Society and designed its membership card. (9)

Emily Ford's painting, Towards the New Dawn was described as a feminist painting and was given by Millicent Fawcett to Newnham College in 1890. The painting, an allegory imbued with renewed and potentially radical significance thanks to its new title and location, was hung in Newnham’s Common Room, where it would have been visible to staff and students. (10)

Emily and her sister Isabella Ford, influenced by their friend, Edward Carpenter, both became socialists and helped form a Leeds branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Other local members included Mary Gawthorpe and Ethel Annakin, who were also active in the struggle for women's suffrage. (11) As a member of the Women's Trade Union League Ford supported strikes of women weavers and the tailoresses in 1888 and 1889 with practical assistance and contributions towards the strike fund. (12)

According to Dora Meeson Coates, Emily Ford's cottage and studio at 44 Glebe Place, provided a meeting place for "artists, suffragists, people who did things. She had been a great beauty and, though no longer young... was still full of charm, with a wondrous energy for life and work." (13)

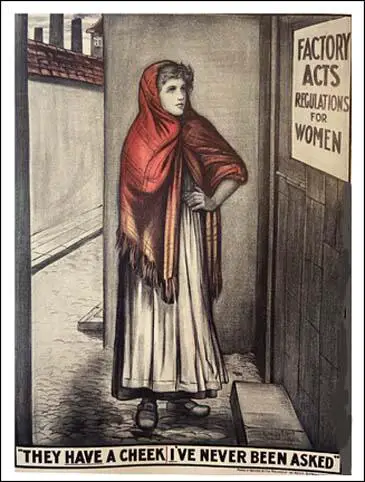

In 1908 Emily Ford produced one of the Artists' Suffrage League's most popular posters, "Factory Acts. They Have a Cheek. I've Never Been Asked." It was a protest against the various Factory Acts where the regulations governing women's work were made by men without consulting women workers. The art-work was also produced as a post-card that was sold at meetings. (14) It was also used by The Common Cause to illustrate an article on how the vote would affect the position of working women. (15)

1909 ASL Competition

The Artists' Suffrage League organised competitions on behalf of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. As Lisa Tickner has pointed out: "There is some suggestion that competitors needed help in formulating their ideas, and designers were encouraged to send in thumbnail sketches in advance. Even trained artists could be ignorant of the particular requirements of a picture poster, and good designs that would make an impact and reproduce efficiently were difficult to come by." (16)

In February 1909 a prize of £5, together with several smaller prizes of one pound each, was offered by the Artists' League for "the best design for a poster, suitable for use in elections." (17) It is estimated that over thirty artists entered the competition. Philippa Strachey, the secretary of the London Society for Women's Suffrage suggested to her cousin, the artist Duncan Grant, submit an entry. Grant submitted Handicapped! and shared the first prize of £5. (18)

The Common Cause newspaper described it as depicting "a stalwart Grace Darling type struggling in the trough of a heavy sea with only a pair of sculls, while a nonchalant young man in flannels glides gaily by, with a wind inflating his sail - the vote - treating with good temper a subject which often causes bitterness." (19) It has been argued that it was "one of the most successful and striking of suffrage designs." (20)

Caroline Watts

Caroline Watts became a member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. and the Artists' Suffrage League (ASL). In 1908 Watts produced The Bugler Girl to advertise the important June 1908 NUWSS procession. Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "The central figure in this, the 'Bugler Girl', is closely associated with the heroic images Caroline was creating for the books commissioned by David Nutt and in 1908 struck a suitably chivalric note." (21) Lisa Tickner explained why it became such an important posters: "A woman trumpeter, standing on ramparts, flag in hand, and blowing an inspiring call to the women of Great Britain to come out and stand by their sisters in this fight." (22)

The image created by Watts appeared on NUWSS posters and pamphlets. It was also used on a badge given to NUWSS's paid organisers. A member of the NUWSS governing-council argued in The Common Cause: "Our Bugler Girl carries her bugle and her banner; her sword is sheathed by her side; it is there, but not drawn, and if it were drawn, it would not be the sword of the flesh, but of the spirit. For ours is not a warfare against men, but against evil." (23)

Banners for Processions

In an attempt to persuade Henry Campbell-Bannerman and his government to give women the vote the NUWSS decided to hold its largest demonstration in its history. The Artists Suffrage League was asked to produce posters and banners for the march. (24) Organised by Philippa Strachey the United Procession of Women took place on 9th February 1907. It was a completely peaceful demonstration where more than three thousand women marched from Hyde Park Corner to the Strand in support of women's suffrage. It acquired the name "Mud March" from the day's weather, when incessant heavy rain left the marchers drenched and mud-spattered. (25)

The Artists Suffrage League was responsible for the design and execution of seventy to eighty embroided banners, which was shared out between a large number of women beyond the membership of the League itself. In 1909 it brought out four posters, six postcards and two Christmas cards. That year 34 members of the League produced banners for the Pageant of Women's Trades and Professions for the International Suffrage Alliance in April, 1909. (26)

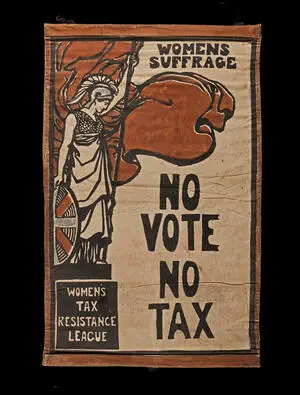

On 22nd October 1909 when the Women's Freedom League (WFL) established the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL). (27) Mary Sargant Florence was a founder member and was on its committee. (28) Florence designed a badge for the WTRL, showing a ship under sail and the slogan, "No Vote, No Tax". She also designed a poster depicting a Britannia figure, holding a a flowing "Reform" banner, and was used as a blank advertising poster, to be filled in with details of a society's meetings. The same design was also used for postcards. A painted banner was used in the 18th June 1910 WSPU procession. (29)

According to the The Suffrage Annual and Women's Whose Who (1913) "The Artists Suffrage League... published many illustrations, leaflets, and posters, which have been in continual demand in all parts of the country, and have played a part in General Elections and all by-elections since 1907. Another important branch of the work undertaken by the League has been the designing and producing of many beautiful banners for the various Branch Societies and Federations of the National Union. These banners have been carried in numbers of Suffrage processions, and have served on the occasion of important political meetings in favor of the Suffrage to decorate the great halls in London and in large provincial cities." (30)

Dora Meeson Coates

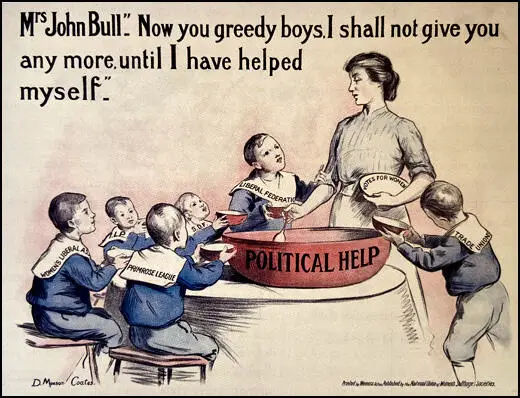

Dora Meeson Coates was a founder member of the Artists' Suffrage League (ASL). In 1908 Coates entered a NUSS poster competition. According to the Women's Franchise newspaper she took first place beating her friend Emily Harding Andrews into joint second place. The judges commented that they found it impossible to decide on which was the better, Miss Williams's design being the more artistic, while Mrs Andrews' would reproduce better". (31)

Dora's poster shows "Mrs John Bull" holding an empty dish labelled "Votes for Women" while six boys - Primrose League, Trade Unions, Liberal Federation, Women's Liberal Association, Social Democratic Federation and Independent Labour Party - clamour for more soup from a large bowl labelled "Political Help". The mother says: "Now you greedy boys I shall not give you any more until I have helped myself." (32)

Dora also painted the 1908 London suffrage march union banner and designing posters and postcards to publicise similar marches. Dora worked with Cicely Hamilton and Mary Lowndes and contributed powerful line drawings to the Artists' Suffrage League publications Beware! A Warning to Suffragists (1909) and A.B.C. of Politics for Women Politicians (1910). (33) During this period she contributed articles and art work for The Common Cause and The Englishwoman. (34)

The Artists' Suffrage League (ASL) produced its own Christmas Cards as a means of spreading information about the need for women's suffrage. Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out in her book, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018): "Between January 1909 and January 1910 the ASL issued four posters, six postcards, and two Christmas Cards, and held one meeting... The 1910 Annual Report reveals that the ASL published 7,000 postcards that year, 25,000 picture leafletrs, 6000 Christmas Cards, and 4000 posters." (35)

In about 1909 Susan Beatrice Pearse, a successful book illustrator, came into contact with the Artists' Suffrage League and spent time in the artist community in Blewbury. In December 1909 Pearse produced a Christmas Card for the organisation. "Miss Pearse's charming Christmas Card in colour was very successfully reproduced by Carl Hentschel, and has been much liked, and has had a large sale." The card was sent to all those Members of Parliament who had declared to be in favour of women's suffrage. (36)

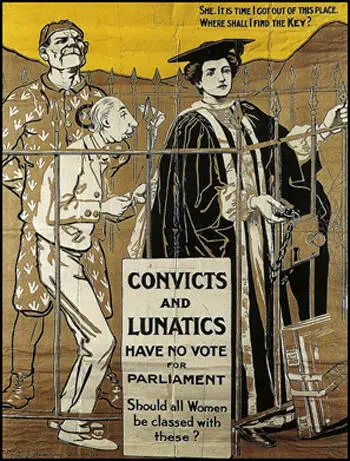

Emily Harding Andrews produced the famous poster, Convicts lunatics and women! Have no vote for parliament: Is it time I got out of this place - Where shall I find the KEY?. It showed a woman wearing cap and gown standing inside locked gates with a convict and a lunatic. The ASL published the poster in 1908. It proved so popular that it was reprinted in 1910. "The strong image, dominated by the glamorously dignified woman graduate, did indeed reproduce well in colour and was also published by the ASL as a black and white postcard." (37)

Records show that the following members of the Artists' Suffrage League contributed designs during this period: included Mary Lowndes, Dora Meeson Coates, Caroline Watts, Emily Harding Andrews, Susan Beatrice Pearse, Emily Ford, Mary Sargant Florence, Charlotte Charlton, Joan Harvey Drew, Bertha Newcombe, Barbara Forbes, May Barker, Clara Billing, Ellen Woodward, Mary Wheelhouse, Christina Herringham and Harriet Adkins. (38)

Suffrage Atelier

Alfred Pearse, Laurence Housman and Clemence Housman formed the Suffrage Atelier (an artists' collective campaigning for women's suffrage) on 8th May 1909. (39) It claimed: "The object of the society is to encourage Artiststo forward the Women's movement, and particularly the Enfranchisement of Women, by means of pictorial publications. Each member of the Society shall undertake to give the Society first refusal of any pictorial work intended for publication, dealing with the women's movement. In return the artist will receive a certain percentage of the profits arising from the sale of her or his work." (40)

As Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) has pointed out that along with the Artists' Suffrage League: "Women were able to organise collectively and contribute their professional skills to the suffrage campaign. They designed, printed and embroidered all manner of political material; they taught each other the requisite skills from hand-painting to needlework; they designed major demonstrations and took part in them in their own contingents; they lent their studios for meetings and contributed to exhibitions, bazaars and fund-raising activities." (41)

Catharine Courtauld

Catharine Courtauld was one of the Suffrage Atelier's most active members. Her brother, Samuel Courtauld, was the head of the Courtauld textile business. (42) An art collector, he later founded the Courtauld Institute. (43) Catherine established herself as an artist living at 4a Upper Baker Street, London. On two occasions Catharine Courtauld exhibited her sculpture at the London Salon that had been established by the Allied Artists Association. (44)

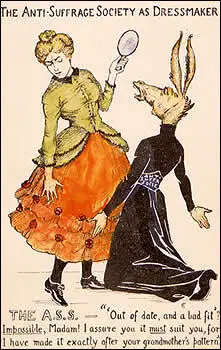

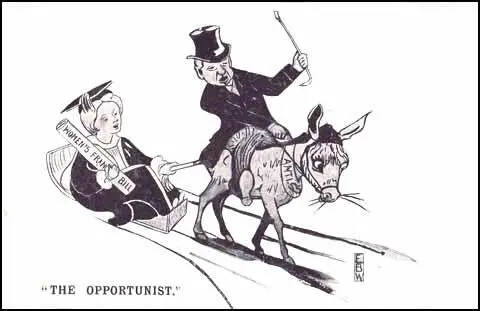

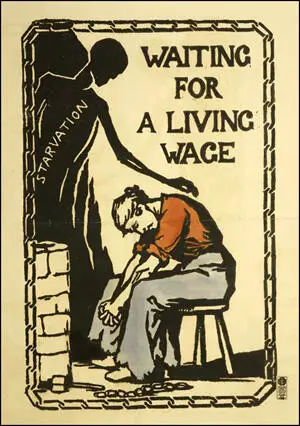

In 1908 Catharine Courtauld joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. The following year she joined the Suffrage Atelier. Several of her designs, such as The Anti-Suffrage Ostrich (c.1909), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Portrait Painter (c.1912), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Prophet (c.1912), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Dressmaker (c.1912), The Prehistoric Argument (1912) and Waiting for the Living Wage (c. 1913) were produced as postcards. (45) Her monogram was usually "c" within a larger "C". (46)

Alfred Pearse

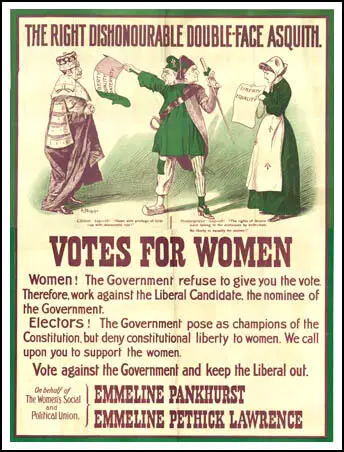

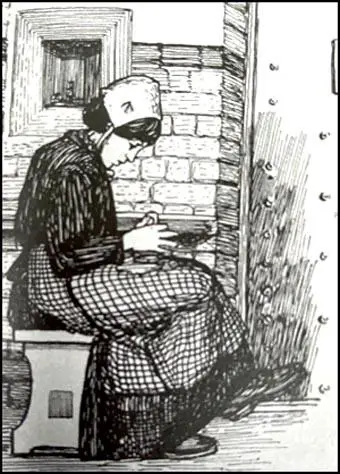

Alfred Pearse, a strong supporter of women's suffrage, was one of the founders of the Suffrage Atelier. Pearse composed a weekly cartoon for the Women Social & Political Union newspaper, Votes for Women from 18th February 1909. (47) One of his most important cartoons depicts the force-feeding of an imprisoned suffragette on a hunger strike - "a practice that the government authorized in 1909". (48)

Most of the Women Social & Political Union posters published between 1909-1914 that survive are signed by Alfred Pearse or in his style. Pearse was a highly competent illustrator, and his drawings for The Vote, Votes for Women and The Suffragette, using the name "A Patriot", helped to give the suffrage newspapers their attractive and professional tone. It seems that Pearse did not charge women's groups for his work. (49) Some of his drawings were issued as postcards. Pearse also worked as an art critic for the Manchester Guardian. (50)

Clemence Housman

The Suffrage Atelier was based at 1, Pembroke Cottages, Edwardes Square, the home of Laurence Housman and Clemence Housman. Laurence described his sister as the organistion's "chief worker" and the main "banner-maker" of the women's suffrage campaign. (51) In 1911 she made a new banner for the Actresses' Franchise League. "Stencilled in the AFL colours of pink, white, and green, it shows the twin masks of tragedy and comedy framed with wreaths and ribbons." (52)

Laurence and Clemence were two of seven children of Edward Housman (1831–1894), a solicitor, and his wife, Sarah Jane Williams (1828–1871). There brother was the poet, Alfred Edward Housman. Assisted by a legacy of £500 each, Laurence and Clemence moved to London in November 1883. They found lodgings at 36 Camberwell New Road. Clemence had been working long hours as a clerk for her father, but now gained employment as a wood-engraver, at first providing illustrations for such weekly illustrated papers as The Graphic and the Illustrated London News. (53)

Laurence Housman studied art at the Lambeth School of Art and the Royal College of Art. A talented illustrator, his work was exhibited at the Baillie Gallery, the Fine Art Society, and the New English Art Club. His best known work includes Goblin Market (1893) and The Sensitive Plant (1898). He also published two volumes of poetry, Green Arras (1896) and Spikenard (1898). In 1900 he created great controversy when he published An Englishwoman's Love Letters. It was very successful and it is claimed he received over £2,000 in royalties. During this period he also worked as an art critic for the Manchester Guardian. (54)

Laurence and Clemence both worked tirelessly for women's suffrage. Laurence had been converted to the cause by hearing a speech given by Emmeline Pankhurst. This resulted in him developing "that most uncomfortable thing a social conscience." He added "I was forced, against my inclination, into a higher standard of moral courage than I had ever practised before" and this began his involvement in the "political problems and controversies of the present day." (55)

In 1907, Laurence Housman joined with several other left-wing intellectuals, including Henry Nevinson, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Henry Harben, Gerald Gould and Charles Mansell-Moullin to formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men." (56)

In a speech made in June, 1909, Laurence Housmen outlined the importance of the Suffrage Atelier. He argued that art had longed suffered from a lack of connection with life in this country. "Pre-Raphaelitism had been an attempt to re-unite art and national life, but the growth of internationalism in technique had not been connected with any international idea or inspiration, such as the Women's Movement now supplied. The pageants of the present day, the revival of old folk-song and dance, and of something resembling a national costume in the purple, green, and white – or green, gold, and white of the Suffrage societies, were signs of the renewal of the blending of art and life." He added that when England invaded other countries "it was represented by John Bull, but when a really national crisis intervened the national spirit was symbolised by Britannia, the woman. Our representative house, in its more heroic moods, called itself the 'Mother of Parliaments'; at present it resembled rather an absconding father." (57)

Housmen's friends accused him of becoming obsessed with the subject of women's suffrage. The author, Alfred Sutro commented in his memoirs that "he was full of high spirits till he became an ardent advocate of 'Votes for Women', an admirable cause that seemed to have a somewhat depressing effect upon its more enthusiastic adherents" (58) The composer Arnold Bax recalled visiting Housman's home and seeing every room hung with suffrage slogans "like Christmas decorations" and that it "was almost the only topic of conversation". (59)

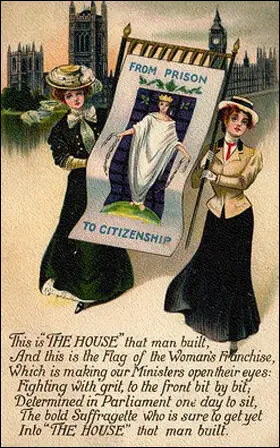

Clemence Housman was heavily involved in the making banners for the Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17th June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. This included the banner "From Prison to Citizenship" under which "almost 1,000 ex-prisoners marched". The banner was made by Clemence from a design by Laurence Housman. The banner was described by Laurence in a letter to his friend Janet Ashbee: "My banner for the Kensington WSPU is practically finished. Everybody says it is the most beautiful that has been done." (60)

Votes for Women commented: "The Kensington Union banner designed by Mr Laurence Housman and worked by the members of the Union, showed the symbolic figure of a woman with broken fetters in her hand, and the words: 'From Prison to Citizenship'. The figure is in white on a purple ground, across which are trailing green leaves." (61) It was such an impressive design that it was featured on a postcard that was published in a series of twelve entitled, "The House that Man Built." (62)

by Clemence Housman from a design by Laurence Housman (1911)

Elizabeth Oakley, the author of Inseparable Siblings: A Portrait of Clemence and Laurence Housman (2009) has argued: "The banners that Clemence and her friends worked so hard to produce must have been among the most eye-catching creations of the Atelier. By using the traditional sewing associated with women's place in the home as propaganda to free them from it, the Atelier had a subversive agenda." (63)

As Mary Lowndes pointed out in her pamphlet On Banners and Banner-Making that in the past it had been women's work to make colourful banners for men to go to war throughout the centuries but for the first time in history such banners were being used "to illumine women's own adventure". She added: "A banner is not a placard... a banner is a thing to float in the wind, to flicker in the breeze, to flirt its colours for your pleasure, to half show and half conceal a device you long to unravel: you do not want to read it, you want to worship it." (64)

As well as being a key member of the Suffrage Atelier, Clemence Housman was active in the Women Social & Political Union and on the committee of the Women's Tax Resistance League. On 30th September 1911 she was the first woman to be arrested for refusing to pay inhabited house duty. When she refused to pay the fine she was sent to prison. The case received a great deal of publicity in the newspapers. "She was released after a week, no reason being given, and did not pay her debt until she received the right to vote." (65)

Louise Rica Jacobs

Louise Rica Jacobs was educated at home by a live-in governess, before studying at the Hull School of Art and in 1903 she was awarded a Government free studentship at the Royal College of Art. A winner of a National silver medal and book prize for figure design in tempera and in 1905 a prize for "the best set of sketches in black and white" awarded in a competition held by the RCA Sketching Club. (66)

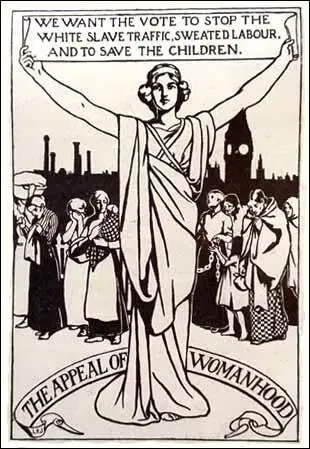

Jacobs became a member of the Suffrage Atelier and designed the "Appeal of Womanhood" for the Coronation Procession which cited the impelling reasons why women wanted the vote - "To stop the White Slave Traffic, Sweated Labour and to Save the Children". According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018): "The Appeal of Womanhood was issued both as a black and white postcard, which is sometimes found partially coloured, and, in at least two colourways, as a poster. The image was also emblazoned on a banner carried by the 'Brown Women' on their Edinburgh to London march in the autumn of 1912." (67)

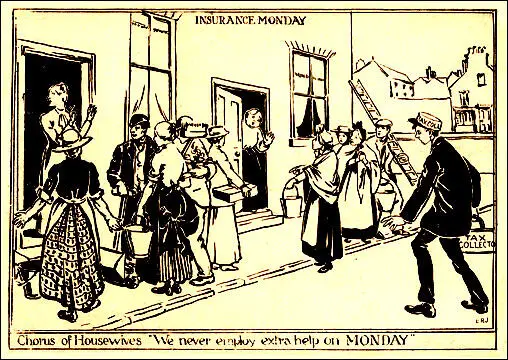

Louise Rica Jacobs was a member of Women's Freedom League (WFL) and provided drawings for The Vote. This included "Chorus of Housewives" that appeared on the front-page of the newspaper in December 1912 and signed "LRJ". (68) This drawing refers to the insurance provisions introduced by David Lloyd George under the 1911 Insurance Act by which domestic employers had to pay for insurance stamps for their servants. (69)

Jacob's cartoon was supporting the Women's Tax Resistance League whose members refused to pay several different taxes including national insurance, Imperial taxes dog licences, duties on carriages and carts and inhabited house duty. In other branches, members tended to make their resisting colleagues' cases the focus of particular campaigns, as in Brighton where the entire branch rallied to support the actions of their secretary and treasurer who had their goods seized and in lieu of their uncollected inhabited house duty in Edinburgh the members resisted paying taxes on the branch's bank interest, and amiably dismissed the Sheriff Officer when "he called to expostulate with us." (70)

In 1913, Louise Rica Jacobs completed a mural, 8ft by 14ft, entitled "The granting of the Commune to the citizens of London by Prince John in 1191" for the first-floor hall of the Commercial Street School, a London Board school. Louise Rica Jacobs was described at the time as a "a Hull artist associated with the Suffrage Atelier, a women’s suffrage group, won the commission in competition." (71) Jacobs also had an exhibition at the Walker Gallery. One newspaper stated she had "craftsmanship of a quite distinguished order, and real charm of style." (72)

Suffrage Propaganda

Ethel Willis, the Honorary Secretary of the Suffrage Atelier urged members to supply the organisation "with hand-printed publications - made from wood blocks, etchings, stencil plates etc.... and by organising Local Meetings for the encouragement of Stencilling, Wood Engraving etc., in order that members may learn or improve themselves in the art of printing by hand." (73)

The Common Cause reported on the work of the Suffrage Atelier: "Weekly cartoon-meetings are held for illustrations, with practical demonstrations of the methods of drawing required for the various processes of pictorial reproduction, so that members may be property qualified to turn out work adapted to reproduction as cartoons, posters, etc. Hand-printing is also practised, so that the society can produce some of its own publications. By this latter process fresh cartoons could be got out at very short notice and very little expense. This could be particularly valuable at election times, when some-thing topical is often needed at once." (74)

It has been argued that the women's suffrage movement were slow to realise the importance of art in the struggle for equal rights. The Vote newspaper later argued: "The value of pictorial art in Suffrage propaganda has not hitherto been sufficiently recognised, until the Suffrage Atelier began its valuable work of educating the public by its pictorial displays, political pictures had scarcely been thought of in the suffrage world." (75)

Ethel Willis of the Suffrage Atelier listed seventeen ways of forwarding the cause. "These included sending in designs for propaganda, or fine art and craft work for exhibition; helping with secretarial work; selling posters and postcards or getting them placed in the press; contributing to pageants and decorative schemes; collecting funds and obtaining more members; forming local branches (there is no evidence that these existed); contributing cuttings, including photographs, illustrations and cartoons for general reference; providing hospitality in studios or drawing rooms for meetings, exhibitions and social occasions." (76)

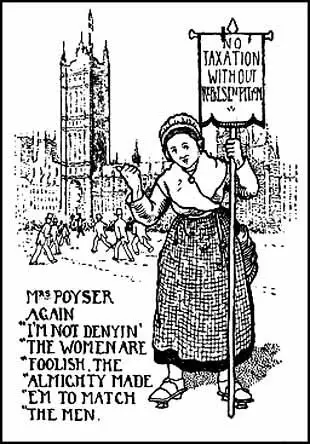

Muriel Matters of the Women's Freedom League was a strong supporter of the Suffrage Atelier organisation. She argued at a meeting in London about the usefulness of pictures as propaganda. "She had found people who were impervious to argument and reason convinced by the postcard representing the lunatic and the lady, or an illustration of Mrs. Poyser's classic remark on men and women." This was a reference to the character Rachel Bede in George Eliot's novel, Adam Bede, published in 1859. (77)

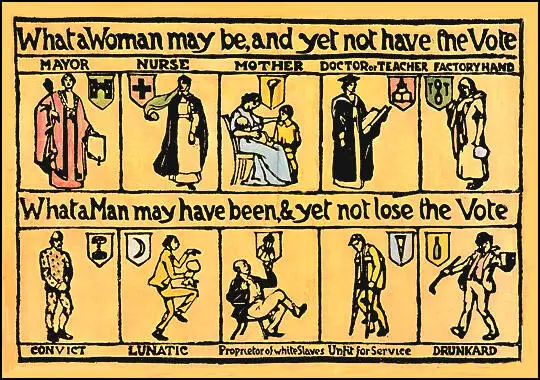

The Suffrage Atelier purchased its own hand-printing press. It formed a "Cartoon Club" that specifically included instructions in hand colour printing and in process-block reproduction. (78) Unlike the Suffrage Atelier it printed its own designs. This included postcards, posters and calenders. (79) Most of the posters and postcards are block prints such as wood or lino-cuts in black and white or hand-coloured. (80) A good example of this is the one below that compares male convicts, lunatics and drunks with the vote with women with responsible jobs who did not have this right. (81)

To encourage new ideas the Suffrage Atelier regularly held competitions. In April 1910 Votes for Women reported that the "Suffrage Atelier has arranged a competition of designs for posters, large and small, and of designs for banners in embroidery and applique. Various prizes are offered." (82)

The Suffrage Atelier functioned as an educational and social centre with a regular programme of activities that mixed instruction, criticism, designing, printing, banner-making and life drawing with exhibitions and guest speakers. It solicited contributions and offered prizes for successful designs. (83) In doing so it tried to reconcile two aims at the same time: to be of use to suffrage societies in the campaign, but also to afford women artists "opportunities to experiment and... to become acquainted with the processes of reproduction." (84)

The Suffrage Atelier provided art lessons. The organisation arranged for members to draw and paint live models. Votes for Women pointed out: "At these meetings there will be sketching from life (some well-known Suffragists will sit, whenever possible), and all kinds of technical information connected with the society's work will be given." (85) The Suffrage Atelier also provided sessions on public speaking. (86)

Leading members would take it in turns holding "At Home" sessions on the last Thursday in every month. Ethel Willis invited people to her home at 6 Stanlake Villas, Shepherds Bush on several occasions. One journalist was very impressed with one session she attended where Louise Rica Jacobs was showing her work: "The Atelier is run entirely by women artists, who make their own designs, cut blocks and do the printing of posters, postcards, Christmas cards and pictorial leaflets, the uniform of the women being a bright blue workmanlike coat, a black skirt, and a big black bow like that beloved of the artists who dwell near the Luxemburg." (87)

The artist, Dora Meeson Coates, also held "At Home" meetings at her Chelsea Studios. "A large number of Suffragists of all shades gathered to press forward the poster and pictorial campaign which the organisation has so successfully carried on for a considerable time, greatly to the advantage of all other societies, who benefit by this form of advertisement and illustration. Mrs. Fagan, addressing the gathering, made an appeal for money to pay a secretary and a traveller. She felt that the worst sweated labour she knew of was involved in the production of these posters. A traveller was wanted, a woman with charming manners and a determined effort to visit branches of all Suffrage societies, her idea being that every branch of every society should have at least one poster on hoarding near their shop, or even their private address, of meetings, at a cost of £2 per year." (88)

The Suffrage Atelier also organized lectures on a wide-variety of subjects. For example, on 16th March 1910, Dr. Kate Haslam, gave a lecture on "Women in the Medical Profession". (89) The following month she was talking about "English Poor-Law in the 19th Century" at the home of Clemence Housman. (90) In October 1912, the arist, Dora Meeson Coates, a founder member of the Artists' Suffrage League (ASL), arranged "an exhibition of posters and other pictorial work" at her studio. (91)

In December 1911, the Suffrage Atelier held a Christmas party and exhibition of their work at an artist studio in Shepherds Bush that was hosted by Katherine Vulliamy of the Women's Freedom League. "In spite of the wet weather many friends arrived, each bearing a Christmas present, presents which ranged from a mangle to a file – all of great value to the Atelier…. After tea the guests inspected the work shown in the various departments, including original drawings and designs, posters, postcards, and Christmas cards, designed and printed at the Atelier. Mrs Vulliamy of the Women's Freedom League, spoke on the work of the Atelier dwelling chiefly on its value to the Suffrage Societies and to women artists as affording them opportunities to experiment and also to become acquainted with processes of reproduction." (92)

The Suffrage Atelier produced broadsheets which reproduced available designs in miniature so that prospective customers could make their selection. In 1912 their broadsheet offered twenty-nine available designs (almost three times as many as the Artists' Suffrage League produced in the same period. Lisa Tickner argues that "despite their ephemeral nature over forty different posters and about fifty postcards still survive." (93)

Women's Freedom League

Initially most members of the Suffrage Atelier were members of the Women Social & Political Union. However, several members became critical of its arson campaign and left the organisation. Laurence Housman, one of the co-founders of the Suffrage Atelier was especially critical of the WSPU. He was especially upset when Mary Richardson attacked the painting, Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez at the National Gallery. Housman described the "stab in the back given to the Rokeby Venus" as hurting his artistic feelings. "After that came the burning of churches, and I felt myself obliged to cease subscribing to WSPU funds." (94)

The Suffrage Atelier now became closely associated with the militant but non-violent, Women's Freedom League (WFL) with which it embarked on the joint venture of a "pictorial supplement" with its newspaper, The Vote. (95) In 1912 the WFL worked with the Atelier on a new poster campaign. Charlotte Despard, the leader of the WFL, wrote that their joint campaign would bring the Atelier's work "into more intimate relation" with the movement and the public as a whole, while at the same time illustrating "the advance of the Cause and the fluctuations of the political barometer". (96)

In October 1912, Ethel Willis held a "At Home" at her home at 6 Stanlake Villas, Shepherds Bush where the lithographs of Louise Rica Jacobs, the cartoons of Alfred Pearse, that had appeared in The Vote, and posters produced for the Women's Freedom League were exhibited. Also on display were "Mrs. Ambrose Gosling's beautiful lace and wonderful needlecraft." (97)

WSPU

Sylvia Pankhurst studied at Manchester Art School. She was later to recalled she enjoyed the avant-garde atmosphere of art college and "when absorbed in the work I knew the greatest happiness." (98) In 1900 she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in South Kensington. Women had been admitted from its formation but in a segregated "Female School" with a different curriculum, including life classes in which the live models were strictly, clothed." (99)

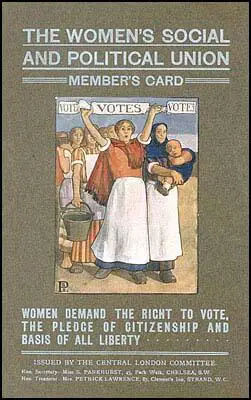

Although a committed artist, Sylvia began spending more and more time working for women's suffrage. When the Women Social & Political Union was formed, Sylvia employed her artistic skills for the organisation. This included designing the Membership Card for the WSPU. It portrayed "in clear, bright colours, the working women, in aprons, clogs, and shawls, whose lives she hoped the campaign would improve." (100)

Lisa Tickner argues that political conflicts with her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, and her sister, Christabel Pankhurst, reduced her contribution to the pictorial propaganda of the campaign: "She was increasingly divided from her mother and Christabel over questions of allegiance and strategy. She deplored what she saw as the neglect of the needs of working-class women, and the severing of ties with the socialist movement." (101)

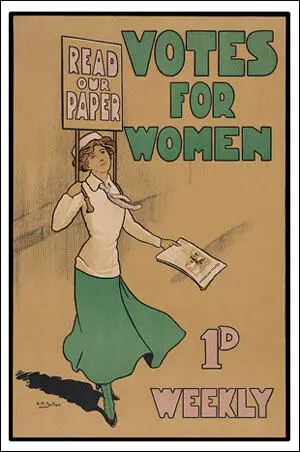

The Women Social & Political Union established its own newspaper, Votes for Women in October 1907. Its first editors were the husband and wife team of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. The newspaper was printed by the St. Clement's Press. It was originally a monthly but after April 1908 it was published every week. At this time sales reached 5,000 copies a month. In 1909-10 the paper reached the zenith of its circulation, having risen in that year from 16,000 copies weekly to nearly 40,000. (102)

Sylvia Pankhurst decided to get herself imprisoned and then go on hunger-strike. She told Keir Hardie: "I shall have to go to prison to stand by the others". He responded that the movement didn't need any more martyrs, it needed her art. "Finish what you are working on at least." Sylvia agreed to wait but was determined to join other members of the WSPU in their hunger-strike campaign. (103)

In 1909 Sylvia Pankhurst and Keir Hardie rented a cottage in Penshurst, Kent. They met there as often as his busy schedule permitted. According to Fran Abrams: "During one of these interludes he begged her not to go back to prison. The thought of the feeding tubes and the violence with which they were used was already making him ill - how much worse would it be if it were her?" (104) Hardie became one of the main critics of the force-feeding of women prisoners: "That there is difference of opinion concerning the tactics of the militant Suffragettes goes without saying, but surely there can be no two opinions concerning the horrible brutality of these proceedings? Women, worn and weak by hunger, are seized upon, held down by brute force, gagged, a tube inserted down their throats and food poured or pumped into the stomach." (105)

On 14th February 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst and Zelie Emerson, were arrested from throwing a stone at the window of the police station in Bow. They were arrested and sentenced to six weeks in prison. After going on hunger strike they were released. On 17th February, they broke windows of a branch of Westminster Bank in Bow Road. (106) As Fran Abrams has pointed out: "On the first two occasions her efforts were thwarted when her fines were paid and she was released - the first time she blamed WSPU officials, the second time her mother." (107)

This was followed by damaging the greens of Bradford Moor golf course. The magistrate said that if the women behaved as "common riffraff" then they must be treated as such and they were both sentenced to two months' hard labour. (108) Zeli and Sylvia served their sentence in Brixton Prison. They went on hunger and thirst strike and were placed in the hospital wing and force-fed. (109)

According to Rachel Holmes: "Sylvia went on hunger strike and was force-fed more times than any other suffragette. Her mother hunger struck, but was never force-fed. The government appeared to be nervous of the public response to abusing so popular an iconic matriarchal, middle-class figure. Christabel, at the time running the leadership-in-exile from Paris, was not required to hunger strike and hence was never subjected to torture." (110)

Hilda Dallas, had studied at the Slade School with Olive Hockin. Over the next few years she exhibited on eighteen occasions at the Allied Artists' Association and also had a painting accepted by the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. Dallas joined the WSPU in 1910 and produced two posters to promote Votes for Women during this period. (111)

At a meeting in France, in October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (112)

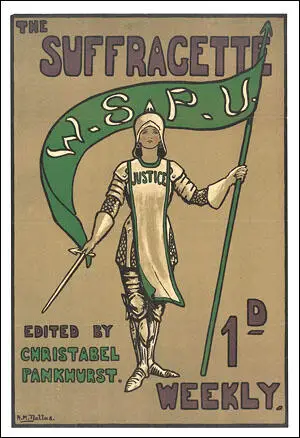

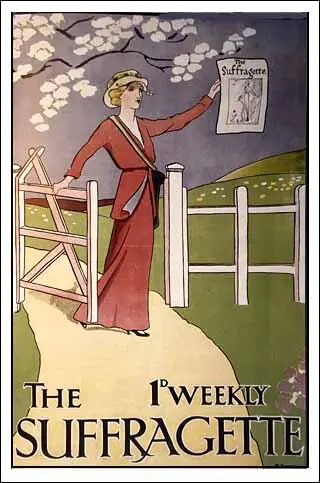

As a result of this expulsion, the WSPU lost control of Votes for Women. They now published their own newspaper, The Suffragette. Edited by Christabel Pankhurst, its first edition was published on 17th October, 1912. (113) Hilda Dallas was given the task of producing a poster for the new newspaper. "The poster showed a Joan of Arc figure, girded in armour, wearing the tabard of 'Justice' and carrying a pennant bearing the letters WSPU." (114)

Initially, the circulation of the newspaper was about 17,000. The Home Office tried to suppress the newspaper. On 2nd May 1913 Sidney Granville Drew, the managing director of Victoria House Printing Company which printed the newspaper, was arrested. He was only released when he promised not to print the newspaper or any other literature of the WSPU. (115)

The artist Margaret Bartels, also produced posters for the Women Social & Political Union. Bartels, who was "very senstive" and did not like attracting public attention. (116) However, she was willing to go out chalking pavements in order to advertise suffrage meetings and in September 1912 was charged with defacing the pavement at Norwood Road, Herne Hill. Found guilty she was fined two shillings. (117) Bartels produced a poster advertising the WSPU newspaper, The Suffragette. in 1913. (118) In addition she contributed the cover illustration for the newspaper in April, 1914. (119)

Margaret Morris, was an important dancer and choreographer. She went into partnership with John Galsworthy in founding a school of dancing in St Martin's Lane, London. (120) She was also a supporter of women's suffrage and had given donations to the Women's Freedom League and the Women Social & Political Union and was a member of the Actresses' Franchise League. (121)

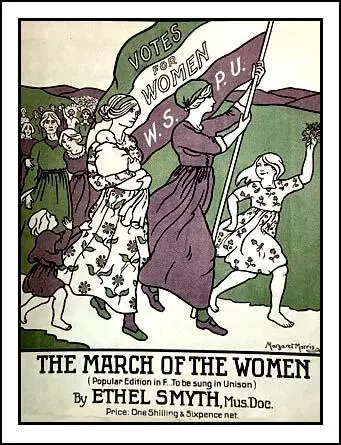

In 1911 the composer Ethel Smyth wrote the music for March of the Women, with words by Cicely Hamilton. It was used by the WSPU during demonstrations. As Sylvia Pankhurst pointed out: "The swelling music of The March of the Women, strong and martial, bold with the joy of battle and endeavour, yet with a lasting undertone of sadness characteristic of that rebellious soul." (122)

Margaret Morris was commissioned to design the cover of the sheet music. Elizabeth Crawford has argued that her art-work shows the influence of Walter Crane. "Using the WSPU colours of purple, white and green Margaret Morris illustrates the women of the country, accompanied by their children, streaming over hill and dale in the wake of the 'Votes for Women' flag. They are gentile, loose-frocked in the Walter Crane style." (123)

Ethel Wright

In 1891 Ethel Wright is recorded as an "Artist Painter" residing at No. 8 Elm Tree Road, Marylebone, London and she told the census enumerator she was 22 years-old which suggests a birth year of 1868 or 1869. (124) Wright developed a successful career, particularly as a society portrait painter, and in 1893 was living in St John's Wood "in the most enchanting of artistic houses and a studio rich in clever portraits and rich imagination." (125)

Bridget Clarke has pointed out that Ethel Wright's portrait was included in The Year’s Art in 1896, as part of a feature on "the more celebrated Lady Artists of the present time." In exhibition, Wright’s work was more often presented or critiqued in the context of "women’s work". (126) Her painting, Bonjour, Pierrot, was "displayed on the conveted line at the Royal Academy in 1892." (127)

Ethel Wright returned to England in 1905. Her marriage difficulties resulted in her becoming a supporter of women's suffrage and became associating with members of the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). He reputation as a portrait painter resulted in the WSPU commissioning her to paint a portrait of Christabel Pankhurst. (128) Rosie Broadley has pointed out: "It is an amazing painting, a historical document as much as portrait. It was supposed to inspire people and present Pankhurst as a figurehead, leading a charge." (129)

The art historian, Alicia Foster, has argued: "In this painting, public heroism is signalled through Pankhurst's grand rhetorical gesture. However it is also allied to 'womanly' elegance and civilisation – skilfully countering the vicious caricatures of suffragettes in some sectors of the press – through the high polish of Wright's style and the sitter's graceful dress." (130) Another art critic as suggested that Wright's painting "embodies the awakened spirit of women." (131)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The painting was purchased for 100 guineas by her friend Una Dugdale one of the leaders of the women's suffrage movement who had given up almost the whole of her spare time to political propaganda." (132) The portrait of Christabel Pankhurst was exhibited at a large exhibition organised by the Women Social & Political Union and funded by Clare Mordan in 1909, and embodies the "awakened spirit" of women that was identified in the catalogue for that exhibition. (133) At the time Ethel Wright was active in the Chelsea branch of the WSPU. (134)

Ethel Wright also painted a portrait of Gabrielle Enthoven an active member of the Actresses' Franchise League (AFL). An organisation established by Edith Craig. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays. Enthoven was a founding member and president of the Pioneer Players, a feminist theatre company that aimed to present plays of "interest and ideas" that dealt with current social, political, and moral issues. (135)

Ethel Wright was in conflict with her husband Bernard Barclay, who was now working as a journalist. She at first she applied for restitution of conjugal rights. When he refused to return in August 1910 she filed for divorce on grounds of “adultery coupled with desertion”. At the time Barclay living with a young woman named Marguerite Jervis (born 1886, Burma) in Hertfordshire. A decree nisi was issued on 21st November 1910, and the divorce was finalised on 29th May 1911. (136)

On 13th January 1912 Una Dugdale married Victor Duval. Duval was a strong supporter of women's suffrage. (137) His sister, Elsie Duval, had been a member of the Women's Freedom League and the Women Social & Political Union. Victor Duval was also the founder of Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement. "The society was formed as a result of a growing conviction among men, as well as women, that the delay in removal of the sex disqualification from the Parliamentary franchise was due to the determined indifference of the Government rather than to any considerable opposition in the country." (138)

It was announced that the word "obey" would be omitted from the marriage service at the Savoy Chapel. However, the Archbishop of Canterbury, sent his representative to tell the Rev. Hugh Chapman, that the omission would make the validity of the marriage doubtful. "The couple acquiesced, and the usual marriage ceremony was proceeded with." (139)

As Catherine Blackford pointed out: "Marriage reform had long been a feminist concern and Duval's standpoint signified a feminist commitment to marriage as an equal partnership based on love and respect rather than subservience and subordination." (140) Later that year she explained her reasons for departing from convention in her pamphlet Love and Honour but not Obey. The illustration on the front page was based on a portrait of Una Dugdale that had been painted by Ethel Wright. (141)

In 1915 Ethel Wright painted a portrait of Lady Beatrice Lever, the former Beatrice Hilda Falk. She was the wife of Sir Arthur Levy Lever, the Liberal Party MP for Harwich. Lady Lever later became one of the 38,000 women who became Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD) during the First World War. VADs worked as assistant nurses, ambulance drivers and cooks. (142)

Ethel Wright lived and worked at 56 Glebe Place in Chelsea, home to many active suffrage artists. (143) Wright continued her association with the suffrage movement whilst continuing to exhibit annually at the Royal Academy until 1927. (144)

The First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (145)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote an article in The Suffragette where she argued: "A man-made civilisation, hideous and cruel enough in time of peace, is to be destroyed... This great war is nature's vengeance - is God's vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection... that which has made men for generations past sacrifice women and the race to their lusts, is now making them fly at each other's throats and bring ruin upon the world... Women may well stand aghast at the ruin by which the civilisation of the white races in the Eastern Hemisphere is confronted. This then, is the climax that the male system of diplomacy and government has reached." (146)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. (147)

Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (148) In another interview she stated: "We suffragists... do not feel that Great Britain is in any sense decadent. On the contrary, we are tremendously conscious of strength and freshness." (149)

Most members of the Women's Freedom League, were pacifists, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 they refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. However, the Suffrage Atelier, that was now closely associated with the WFL, decided to close down on the outbreak of war. This brought to an end an outstanding period of art being produced by people who believed that women should have the vote. (150)