Spartacus Blog

Stanley Baldwin and his failed attempt to modernise the Conservative Party

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". On 22nd January, 1924, Stanley Baldwin, the former prime minister, resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (1)

Baldwin made a speech on 3rd May, 1924, where he commented on the changes that were taking place in politics: "The government had no mandate to govern, and its members won their seats as a Socialistic vote, but were not carving out a Socialist policy. This could be only temporary. If words meant anything the Labour Party was a Socialist Party, and if they went back on socialism they were little more than a left wing of the Conservative Party. Socialism had certain obvious advantages, possessing cut and dried remedies for every evil under the sun, but Conservatives have been in the fore-front of the battle to help the people more… If we are to live as a party we must live for the people in the widest sense… Every future Government must be Socialistic." (2)

Stanley Baldwin and Socialism

Baldwin had always been on the left of the Conservative Party and believed it was sensible to appeal to supporters of the Liberal Party that was clearly in decline. However, it was not only a shrewd political move. Baldwin really believed in a "one nation" conservatism. He had been a successful businessman before entering politics and was proud of his achievements. In his maiden speech in the House of Commons he used his own business experience to explain his views on trade unions: "I might mention, not as of any interest to the House, but merely as showing what the House might expect of me in the way of fair debate, that although my family had been engaged for 130 years in trade, the disputes they had had with their men could be numbered on the fingers of one hand. I myself have been in active business for twenty years, and have never had the shadow of a dispute with any of my own men, and I gave my men in the sheet-rolling trade an eight-hour day long before the question excited any interest in the House or the country. (3)

The Labour government only lasted ten months and on 4th November, 1924, he was once again prime minister. In an attempt to create a more "liberal" Conservative government he wanted to appoint Neville Chamberlain as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Chamberlain had a similar background to Baldwin and was proud of his business background that was based on a good relationship with the trade union movement. When he was elected to Parliament in 1919 he wrote in his diary: "Many people have been sceptical about the suggestion that there was to be a new England, and many others have never intended that it should be very different from the old, if they could help it. If they had had their way, I think we might have drifted into a revolution." However, he was convinced the government could prevent rebellion by being in favour of social reform: "Whether it will be nationalisation in the sense that the State owns and works the collieries, or whether, as is more likely and I think more practical, some State control will be exercised, the workmen having a voice in the direction and a share of the profits." (4)

Chamberlain, however, believed that whereas he might make a great Minister of Health he would only ever be a second-rate Chancellor and requested a move to the Department of Health. Baldwin accepted his arguments and appointed Winston Churchill as Chancellor. Chamberlain immediately embarked upon an ambitious programme of social reform in the areas of housing, health, local government, the extension of national insurance and widows' pensions. Over the next five years he proposed 25 pieces of progressive legislation, 21 of which became law. Graham Stewart argued that "under his guidance, the confused and complicated patchwork of local government was entirely rationalised by 1929 with a commanding sweep which - put to a different goal - would have been the envy of any totalitarian planner." (5)

Baldwin's decision to appoint Churchill as Chancellor of the Exchequer, proved disastrous for his plans to create a political party of the centre. Churchill had no experience of financial or economic matters when he went to the Treasury in November 1924. He made it clear to Sir Richard Hopkins, the chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue that he had no intention of increasing taxes on the rich: "As the tide of taxation recedes it leaves the millionaires stranded on the peaks of taxation to which they have been carried by the flood... Just as we have seen the millionaire left close to the high water mark and the ordinary Super Tax payer draw cheerfully away from him, so in their turn the whole class of Super Tax payer will be left behind on the beach as the great mass of the Income Tax payers subside into the refreshing waters of the sea." (6)

The Conservatism of Winston Churchill

Churchill's first major decision concerned the Gold Standard. Britain had left the gold standard in 1914 as a wartime measure, but it was always assumed by the City of London financial institutions that once the war was over Britain would return to the mechanism that had seemed so successful before the war in providing stability, low interest rates and a steady expansion in world trade. However, at the end of the First World War, the British economy was in turmoil. After a short-term boom in 1919 gross domestic fell by six per cent and unemployment rose rapidly to 23 per cent. (7)

Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England and Otto Niemeyer, a senior figure at the Treasury, were both strong supporters of a return to the gold standard. Niemeyer said to dodge the issue now would be to show that Britain had never really "meant business" about the Gold Standard and that "our nerve had failed when the stage was set." Norman added that in the opinion "of educated and reasonable men" there was no alternative to a return to Gold. The Chancellor would no doubt be attacked whatever he did but "in the former case (Gold) he will be abused by the ignorant, the gamblers and the antiquated industrialists". (8)

On 17th March, 1925, Churchill gave a dinner that was attended by supporters and opponents of returning to the Gold Standard. He admitted that John Maynard Keynes provided the better arguments but as a matter of practical politics he had no alternative but to go back to Gold. (9) Roy Jenkins has argued that the return to the Gold Standard was the gravest mistake of the Baldwin government: "Churchill was deliberately a very attention-attracting Chancellor. He wanted his first budget to make a great splash, which it did, and a considerable contribution to the spray was made by the announcement of the return to Gold. Reluctant convert although he had been, he therefore deserved the responsibility and, if it be so judged, a considerable part of the blame." (10)

As a result of returning to the Gold Standard the country took little part in the world boom from 1925 to 1929 and its share of world markets continued to fall. The balance of payments surplus recorded in 1924 disappeared and overpriced British exports slumped. The overvalued pound meant that costs had to be reduced in an unavailing attempt to keep exports competitive. This meant cuts in labour costs at a time when real wages were already below 1914 levels. Attempts to impose further wage reductions inevitably led to industrial disputes, lock-outs and strikes. It has been estimated that returning to the Gold Standard made as many as 700,000 people unemployed. (11)

Despite the problem of low Government revenues Churchill was determined not to increase personal taxes. In 1925 the majority of people did not pay income tax - only 2½ million people were liable and just 90,000 paid super-tax. The standard rate of income tax was reduced from four shillings and sixpence to four shillings in the pound. The super-tax was reduced by £10 million, which was substantial in relation to the total yield of the tax at £60 million: "This was of substantial benefit to the rich, not only as individual taxpayers but also in the capacity of many of them as shareholders, for income tax was then the principal form of company taxation." (12)

In a letter to James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury, the leader of the House of Lords, he argued that "the rich, whether idle or not, are already taxed in this country to the very highest point compatible with the accumulation of capital for further production." (13) In a second letter he stated that cutting taxes was a "class measure" that was designed "to help the comfortably off and the rich." (14)

Churchill's social conservatism was also apparent during discussions within the Government over changes to unemployment insurance. The scheme that the Liberal government had introduced in 1911 had collapsed after the war because of large-scale structural unemployment, particularly among trades that were not covered by the scheme. A benefit (the dole) was first introduced for unemployed ex-servicemen, later extended to others and then made subject to a means test in 1922. Churchill thought that far too many people were drawing the "dole". (15)

Winston Churchill spoke in the House of Commons of the "growing up of a habit of qualifying for unemployment relief" and the need for an enquiry. (16) Three weeks later he told Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary of the Cabinet, that "there should be an immediate stiffening of the administration, and the position should be made much more difficult for young unmarried men living with relatives, wives with husbands at work, aliens, etc." (17)

Churchill wrote to Arthur Steel-Maitland, the Minister of Labour, to explain his ideas. He suggested that when the legislation to pay for the dole expired in 1926, rather than reduce the benefit, as most of his colleagues wanted to do, they should abolish it altogether. Churchill said: "It is profoundly injurious to the state that this system should continue; it is demoralising to the whole working class population... it is charitable relief; and charitable relief should never be enjoyed as a right." Churchill told Steel-Maitland that the huge number of unemployed families would have to depend on private charity once their insurance benefits were exhausted. The Government might make some donations to charities but money would only be given to "deserving cases" and that "by proceeding on the present lines we are rotting the youth of the country and rupturing the mainsprings of its energies". (18)

Churchill attempted to get his ideas supported by Stanley Baldwin: "I am thinking less about saving the exchequer than about saving the moral fibre of our working classes." (19) Churchill did not get his way. The other members of the Government, including Neville Chamberlain, regardless of any possible moral consequences, could not face the political impact of ending the ‘dole' at a time when over a million people were out of work. (20)

In 1925 Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, urged the government to introduce legislation to reduce the powers of the trade union movement. It was a time of high employment and Churchill believed this was the time to hurt them when they were economically weak. As the government refused to act, a Conservative Party backbench MP, Frederick A. Macquisten, introduced a private members bill that would force trade union members to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party. Macquisten argued that "what I am proposing now is to relieve the working man of this liability to be taxed." (21)

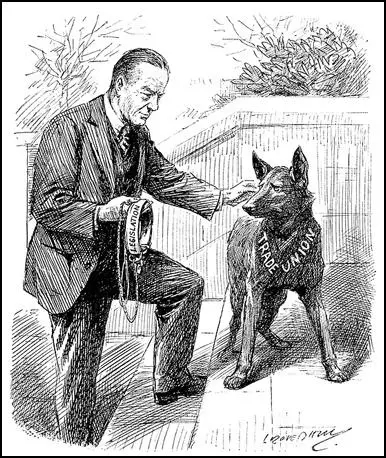

Stanley Baldwin finally decided to make a stand against the right-wing ideas and policies of Churchill. He made a speech in the House of Commons on why he could not support this bill. "Those two forces with which we have to reckon are enormously strong, and they are the two forces in this country to which now, to a great extent, and it will be a greater extent in the future, we are committed. We have to see what wise statesmanship can do to steer the country through this time of evolution, until we can get to the next stage of our industrial civilisation. It is obvious from what I have said that the organisations of both masters and men - or, if you like the more modern phrase invented by economists, who always invent beastly words, employers and employees, these organisations throw an immense responsibility on the representatives themselves and on those who elect them... In this great problem which is facing the country in years to come, it may be from one side or the other that disaster may come, but surely it shows that the only progress that can be obtained in this country is by those two bodies of men - so similar in their strength and so similar in their weaknesses - learning to understand each other, and not to fight each other." (22)

Trade Union Reform

After the defeat of the miners in the 1926 General Strike, Churchill once again put pressure on Baldwin to introduce anti-trade union legislation. This time Baldwin accepted his arguments and in 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservatives who depended on secret donations from rich men." (23)

The legislation defined all sympathetic strikes as illegal, confining the right to strike to "the trade or industry in which the strikers are engaged". The funds of any union engaging in an illegal strike was liable in respect of civil damages. It also limited the right to picket, in terms so vague that almost any form of picketing might be liable to prosecution. As Julian Symons has pointed out: "More than any other single measure, the Trade Disputes Act caused hatred of Baldwin and his Government among organized trade unionists." (24)

One of the results of this legislation was that trade union membership fell below the 5,000,000 mark for the first time since 1926. However, despite its victory over the trade union movement, the public turned against the Conservative Party. Over the next three years the Labour Party won all the thirteen by-elections that took place. Stanley Baldwin considered offering government help to relieving distress in high unemployment areas but Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, insisted that "we must harden our hearts". (25)

Votes for Women

Stanley Baldwin, wanted to change the image of the Conservative Party to make it appear a less right-wing organisation. In March 1927 He suggested to his Cabinet that the government should propose legislation for the enfranchisement of nearly five million women between the ages of twenty-one and thirty. This measure meant that women would constitute almost 53% of the British electorate. The Daily Mail complained that these impressionable young females would be easily manipulated by the Labour Party. (26)

Churchill was totally opposed to the move and argued that the affairs of the country ought not be put into the hands of a female majority. In order to avoid giving the vote to all adults he proposed that the vote be taken away from all men between twenty-one and thirty. He lost the argument and in Cabinet and asked for a formal note of dissent to be entered in the minutes. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. (27)

There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. Many of the women who had fought for this right were now dead including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pankhurst. Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS during the campaign for the vote, was still alive and had the pleasure of attending Parliament to see the vote take place. That night she wrote in her diary that it was almost exactly 61 years ago since she heard John Stuart Mill introduce his suffrage amendment to the Reform Bill on May 20th, 1867." (28)

1929 General Election

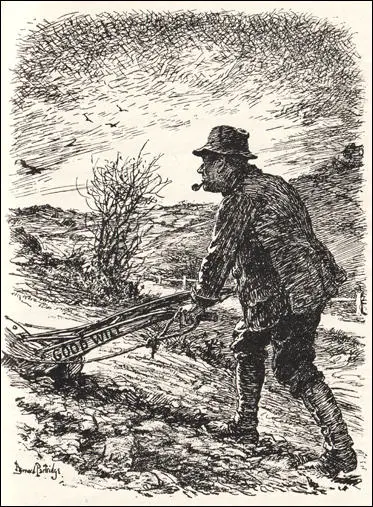

Baldwin firmly believed that he would win the 1929 General Election. He realised that he did not have a good manifesto, "but thought that his reputation as a moderate statesman, calmly if slowly steering the country in the right direction, would overcome that". (29) In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (30)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (31)

In the 1929 General Election the Conservatives won 8,656,000 votes (38%), the Labour Party 8,309,000 (37%) and the Liberals 5,309,000 (23%). However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59. The Conservatives lost 150 seats and became for the first time a smaller parliamentary party than Labour. David Lloyd George, the leader of the Liberals, admitted that his campaign had been unsuccessful but claimed he held the balance of power: "It would be silly to pretend that we have realised our expectations. It looks for the moment as if we still hold the balance." However, both Baldwin and MacDonald refused to form a coalition government with Lloyd George. Baldwin resigned and once again MacDonald agreed to form a minority government. (32)

Winston Churchill was furious with both David Lloyd George and Stanley Baldwin that they had allowed this to happen. Lloyd George argued that he had no choice but to do this as his manifesto promises were much closer to the policies of the Labour Party. Churchill replied: "Never mind, you have done your best, and if Britain alone among modern States chooses to cast away her rights, her interests and her strength, she must learn by bitter experience." (33)

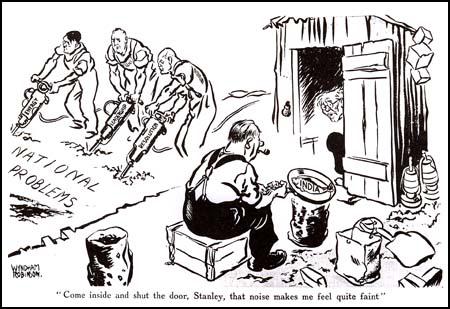

United Empire Party

Lord Rothermere, the leading press baron, believed that Stanley Baldwin did badly in the election because he was too left-wing and probably a "crypto-socialist". The other main press baron, Lord Beaverbrook, agreed with him. Both men were concerned about the government's attitude towards the British Empire. Rothermere agreed with Brendan Bracken when he wrote: "This wretched Government, with the aid of the Liberals and some eminent Tories, is about to commit us to one of the most fatal decisions in all our history, and there is practically no opposition to their policy". Bracken believed that with the support of the Rothermere and the Beaverbrook newspaper empires it would be possible "to preserve the essentials of British rule in India". (34) Beaverbrook xplained to Robert Borden, the former Canadian prime minister: "The Government is trying to unite Mohammedan and Hindu. It will never succeed. There will be no amalgamation between these two. There is only one way to govern India. And that is the way laid down by the ancient Romans - was it the Gracchi, or was it Romulus, or was it one of the Emperors? - that is Divide and Rule". (35)

Rothermere agreed to join forces with Beaverbrook, in order to remove Baldwin from the leadership of the Tory Party. According to one source: "Rothermere's feelings amounted to hatred. He had backed Baldwin strongly in 1924, and his subsequent disenchantment was thought to be connected with Baldwin's unaccountable failure to reward him with an earldom and his son Esmond, an MP, with a post in the government. By 1929 Rothermere, a man of pessimistic temperament, had come to believe that with the socialists in power the world was nearing its end; and Baldwin was doing nothing to save it. He was especially disturbed by the independence movement in India, to which he thought both the government and Baldwin were almost criminally indulgent." (36)

Rothermere and Beaverbrook believed the best way to undermine Baldwin was to campaign on the policy of giving countries within the British Empire preferential trade terms. Beaverbrook began the campaign on 5th December, 1929, when he announced the establishment of the Empire Free Trade movement. On the 10th December, the Daily Express front page had the banner headlines: "JOIN THE EMPIRE CRUSADE TODAY" and called on its readers to register as supporters. It also proclaimed that "the great body of feeling in the country which is behind the new movement must be crystallised in effective form". The appeal for "recruits" was repeated in Beaverbrook's other newspapers such as the Evening Standard and the Sunday Express. All his newspapers told those who had already registered their support to "enroll your friends... we are an army with a great task before us." (37)

In January, 1930, Rothermere's newspapers came out in support of Empire Free Trade. George Ward Price, a faithful Rothermere mouthpiece, wrote in the Sunday Dispatch, that "no man living in this country today with more likelihood of succeeding to the Premiership of Great Britain than Lord Beaverbrook". (38) The Daily Mail also called on Baldwin to resign and be replaced the press baron. Beaverbrook responded by describing Rothermere as "the greatest trustee of public opinion we have seen in the history of journalism." (39)

Beaverbrook wrote to Sir Rennell Rodd explaining why he had joined forces with Rothermere to remove Baldwin: "I hope you will not be prejudiced about Rothermere. He is a very fine man. I wish I had his good points. It (working with Rothermere) would make the Crusade more popular among the aristocracy - the real enemies in the Conservative Party... It is time these people were being swept out of their preferred positions in public life and their sons and grandsons being sent to work like those of other people." (40)

Rothermere now joined the campaign of Empire Free Trade: "British manufacturers and British work people are turning out the best goods to be bought in the world. They are far ahead of their competitors in two of the most important factors - quality and durability. The achievement of our industrialists and workers in the more impressive because they are handicapped in so many ways. Whereas in foreign countries politicians are considerate of industry and do all that is in their power to aid it, here the politicians will not even condescend to tell those few trades which have some slight vestige of tariff protection whether that protection is going to be continued or abolished." (41)

Beaverbrook had a meeting with Baldwin about the Conservative Party adopting his policy of Empire Free Trade. Baldwin rejected the idea as it would mean taxes on non-Empire imports. Robert Bruce Lockhart, who worked for Lord Beaverbrook, wrote in his diary: "In evening saw Lord Beaverbrook who will announced his New Party on Monday, provided Rothermere comes out in favour of food taxes. It is a big venture." Beaverbrook's plan was to run candidates at by-elections and general elections. This "would wreck the prospects of many Tory candidates, thus destroying Baldwin's hopes of a majority in the next Parliament". (42)

On 18th February, 1930, Beaverbrook announced the formation of the United Empire Party. The following day Lord Rothermere gave his full support to the party. A small group of businessmen, including Beaverbrook and Rothermere, donated a total of £40,000 to help fund the party. The Daily Express also asked its readers to send in money and in return promised to publish their names in the newspaper. Beaverbrook presented Conservative MPs with an implied ultimatum: "No MP espousing the cause of Empire Free Trade will be opposed by a United Empire candidate. Instead, he shall have, if he desires it, our full support. If the Conservatives split, they will do so because at last the true spirit of Conservatism has a chance to find expression." (43)

In the Daily Mail Rothermere ran stories about the new party on the front page for ten days in succession. According to the authors of Beaverbrook: A Life (1992): "With their combined total of eight national papers, and Rothermere's chain of provincial papers, the press barons were laying down a joint barrage scarcely paralleled in newspaper history." Rothermere told Beaverbrook that "this movement is like a prairie fire". Leo Amery described Beaverbrook "bubbling over with excitement and triumph". (44)

Beaverbrook later admitted that as a press baron he had the right to bully the politician into pursuing courses he would not otherwise adopt. (45) Baldwin was badly shaken by these events and in March 1930 he agreed to a referendum on food taxes, and a detailed discussion of the issue at an imperial conference after the next election. This was not good enough for Rothermere and Beaverbrook and they decided to back candidates in by-elections who challenged the official Conservative line. (46)

Ernest Spero, the Labour MP, for West Fulham, was declared bankrupt and was forced to resign. Cyril Cobb, the Conservative Party candidate in the by-election, declared that he supported Empire Free Trade and this gave him the support of the newspapers owned by Rothermere and Beaverbrook. On 6th May, 1930, Cobb beat the Labour candidate, John Banfield, with a 3.5% swing. The Daily Express presented it as a win for Beaverbrook, with the headline: "CRUSADER CAPTURES SOCIALIST SEAT". (47)

Rothermere and Beaverbrook wanted Neville Chamberlain to replace Baldwin. They entered into negotiations with Chamberlain who expressed concerns about the long-term consequences of this attack on the Conservative Party. He was especially worried about the cartoons by David Low, that were appearing in the Evening Standard. Chamberlain argued that before a deal could be arranged: "Beaverbrook must call off his attacks on Baldwin and the Party, cease to include offensive cartoons and paragraphs in the Evening Standard, and stop inviting Conservatives to direct subscriptions to him in order that they might be used to run candidates against official Conservatives." (48) Beaverbrook told one of Chamberlain's friends that "nothing will shift us from the advocacy of duties on foodstuffs". (49)

Chamberlain claimed he remained loyal to Baldwin and refused to undermine his leader. He wrote in his diary: "The question of leadership is again growing acute… I am getting letters and communications from all over the country… I cannot see my way out. I am the only person who might bring about Stanley Baldwin's retirement, but I cannot act when my action might put me in his place." (50)

However, Peter Neville, the author of Neville Chamberlain (1992), has argued that there is evidence that Chamberlain spread information amongst fellow members of the Cabinet that undermined Baldwin: "Chamberlain's behaviour during the leadership crisis was not as disinterested as he subsequently maintained. This in itself was not particularly shocking. Politicians are ambitious, and Neville Chamberlain would in 1931 have attained a position which neither his father nor his half-brother had ever achieved - leadership of the Conservative Party." (51)

In June, 1930, Lord Rothermere wrote to Baldwin demanding that the leader of the Conservative Party needed to promise to submit the list of his planned Cabinet ministers if he wished to have the support of the Daily Mail for the next Tory government. Baldwin decided to make the letter public and argued that "a more preposterous and insolent demand was never made on the leader of any political party." He added: "I repudiate it with contempt and will fight that attempt at domination to the end." (52)

In October 1930, Vice-Admiral Ernest Taylor was selected to stand for the United Empire Party in the Paddington South by-election. Herbert Lidiard, the Conservative Party candidate, declared that he was a Baldwin loyalist. Beaverbrook told the nation that the contest was now between a "Conservative Imperialist" (Taylor) and a "Conservative Wobbler" (Lidiard). (53)

Baldwin was warned that the Conservative Party was in danger of losing the seat and if that happened he might be removed as leader. He decided to hold a meeting of Conservative peers, MPs and candidates before the election took place. Beaverbrook made a speech attacking the resolution expressing confidence in Baldwin was carried by 462 votes to 116. Baldwin claimed that Beaverbrook came out very badly out of the meeting: "The Beaver would not have spoken but Francis Curzon challenged him to speak. He was booed and made a poor speech.. and said that he didn't care two-pence who was leader as long as his policy was adopted!" (54)

With the support of the Rothermere and Beaverbrook press, Taylor defeated the official Conservative Party candidate by 1,415 votes. Beaverbrook wrote: "What a life! Excitement (being howled down at the party meeting), depression (being heavily defeated by Baldwin), exaltation (being successful at South Paddington." (55) Beaverbrook wrote to his good friend, Richard Smeaton White, the publisher of The Montreal Gazette: "I believe the Empire Crusade controls London. And we can, I am sure, dominate the Southern counties of Surrey, Sussex, and Kent, and we will dominate Baldwin too, for he must come to full acceptance of the policy." (56)

Rothermere and Beaverbrook became convinced that the way to remove Baldwin was to fight the official Conservative candidate in by-elections. Beaverbrook wrote to Rothermere: "I am going out entirely for by-elections this year, and shall exclude all other forms of propaganda. I shall make the by-elections the occasions for my propaganda." (57) Rothermere replied: "If you are going to build up a real organisation with full intentions of fighting all by-elections, go ahead and you will find me with you." (58)

In February, 1931, a by-election occurred at East Islington after the death of Ethel Bentham. The Labour candidate was Leah Manning. The Conservatives selected Thelma Cazalet-Keir and Air Commodore Alfred Critchley represented the United Empire Party. Beaverbrook spoke at eleven meetings in support of Critchley. One Tory said that "Lord Beaverbrook comes to East Islington and it compared to an elephant trumpeting in the jungle or a man-eating tiger. I am inclined to compare him to a mad dog running along the streets and yapping and barking." Despite this effort, Critchley only split the Conservative vote and the seat was won by Manning. (59)

The next by-election took place in Westminster St George. Lord Beaverbrook selected Ernest Petter, a Conservative industrialist "who will stand in opposition to Mr Baldwin's leadership and policy." The official Conservative candidate was Duff Cooper. However, on the 1st March, 1931, the party's chief political agent reported that there was "a very definite feeling" that Baldwin was "not strong enough to carry the party to victory". (60)

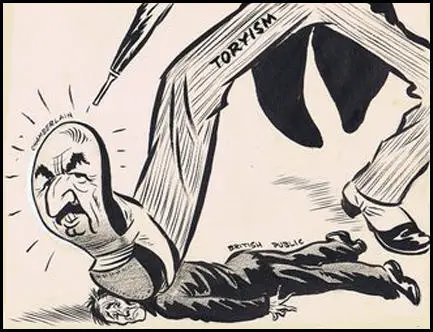

Neville Chamberlain, told Baldwin that his research suggested that the Conservatives would lose the by-election if he remained leader. On hearing the news Baldwin decided to resign. At the last minute William Bridgeman, a close friend and former Home Secretary, persuaded him to postpone his decision until after the Westminster by-election. (61)

The Daily Mail made a crude and abusive attack on Cooper calling him a "softy" and "Mickey Mouse" and accusing him falsely of having made a speech in Germany attacking the British Empire. Geoffrey Dawson of The Times remained loyal to Baldwin and invited Cooper to let him know if "I can do anything... to correct misstatements which the 'stunt' papers decline to admit." The Daily Telegraph also gave their support to Cooper and he was told by its owner that "you will find all our people, editorial, circulation, and everybody doing their damndest for you." (62)

The Daily Mail now made a personal attack on Baldwin and implied that he was unfit for government because he had squandered the family fortune: "Baldwin's father... left him an immense fortune which so far as may be learned from his own speeches, has almost disappeared... It is difficult to see how the leader of a party who has lost his own fortune can hope to restore that of anyone else, or of his country." (63)

Stanley Baldwin considered taking legal action but instead made a speech at the Queen's Hall on the power of the press barons: He accused Rothermere and Beaverbrook of wanting "power without responsibility - the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages" and using their newspapers not as "newspapers in the ordinary acceptance of the term", but as "engines of propaganda for the constantly changing policies, desires, personal wishes, personal likes and dislikes", enjoying "secret knowledge without the general view" and distorting the fortunes of national leaders "without being willing to bear their burdens". (64)

The attacks on Baldwin by Rothermere and Beaverbrook backfired. Duff Cooper won the seat easily. Beaverbrook struggled to come to terms with the result. He wrote: "I am horribly disappointed by the failure. It is much worse than I expected. I cannot believe that Press dictatorship was the reason for it." He told a friend that: "We lost St George's because of the strong cross-currents. It was a baffling contest and we were driven off course. We cannot take the result as a rejection of Empire Free Trade." (65)

Beaverbrook and Rothermere decided to bring the United Empire Party to an end. Rothermere, unlike Beaverbrook, did believe that Baldwin's attack on the press barons did have an impact on the result. He told one of his editors: "The amount of nonsense talked about the power of the newspaper proprietor is positively nauseating... Of course, I have long ceased to have any illusions on the point myself... How could I have any illusions on this score, after the way Baldwin managed to survive years of the most bitter newspaper attacks on his... muddle-headed policies." (66)

Baldwin's Final Years

Although he won his fight with the press barons Baldwin lost his desire to move the Conservative Party to the centre. In 1931 he joined forces with Ramsay MacDonald, to form a National Government. Neville Chamberlain was appointed as the new Chancellor of the Exchequer and in his first budget speech he argued: "Nothing could be more harmful to the ultimate material recovery of this country or to its present moral fibre… hard work, strict economy, firm courage, unfailing patience, these are the qualifications that are required of us, and with them we shall not fail." (67)

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. All those paid by the state, from cabinet ministers and judges down to the armed services and the unemployed, were cut 10 per cent. Teachers, however, were treated as a special case, lost 15 per cent. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249. (68)

Stanley Baldwin became prime minister for the third time when he replaced Ramsay MacDonald in June 1935. However, he made no attempt to bring in any progressive reforms, before he retired from politics on 28th May, 1937. Despite his own failure to achieve his objectives. Baldwin was highly critical of Neville Chamberlain's government. He complained to Anthony Eden that his own work "in keeping politics national instead of party" had been rendered worthless by the actions of Chamberlain. Eden replied that Chamberlain was attempting to "return to class warfare in its bitterest form". (69)

Stanley Baldwin died on 14th December 1947. He lived long enough to see Clement Attlee became prime minister after the 1945 General Election and for the first time saw a government bring in socialistic measures. During his six years in office Attlee carried through a vigorous programme of reform. The Bank of England, the coal mines, civil aviation, cable and wireless services, gas, electricity, railways, road transport and steel were nationalized and socialized medicine was introduced with the National Health Service.

Butskellism

Had Baldwin's prediction made in May 1924, that "Every future Government must be Socialistic" proved correct. For a while it seemed it had. When Winston Churchill took power in October 1951 he made no attempt to undo the socialist reforms introduced by the previous Labour government. This was partly because at the age of 77, he was suffering from the early stages of dementia. According to his biographer, Clive Ponting, he "had difficulty concentrating on an issue as well as a tendency to reminisce at the slightest opportunity... he took little or no interest in economic, financial or domestic policy of any sort." (70)

Rab Butler became Chancellor of the Exechequer and followed to a large extent the economic policies of his Labour predecessor, Hugh Gaitskell, pursuing a mixed economy and Keynesian economics as part of the post-war political consensus. This consensus became known as "Butskellism" and meant that the government tolerated or encouraged nationalisation, strong trade unions, heavy regulation, high taxes, and a generous welfare state. The term was first used by The Economist, when it stated in February 1954, that the "already... well-known figure... Mr Butskell... a composite of the present Chancellor and the previous one". (71)

Butskellism was what Baldwin had predicted by Baldwin in his 1924 speech. It was to last until the election of Margaret Thatcher in May 1979. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown made no attempt the revive the idea but maybe with the election of the next Labour government we might see it return.

John Simkin (15th April, 2019)

References

(1) Robert Shepherd, Westminster: A Biography: From Earliest Times to the Present Day (2012) page 313

(2) Stanley Baldwin, speech at the Junior Imperial League (3rd May 1924)

(3) Stanley Baldwin, speech in the House of Commons (3rd March 1908)

(4) Neville Chamberlain, diary entry (22nd March, 1919)

(5) Graham Stewart, Burying Caesar: The Churchill-Chamberlain Rivalry (2001) page 137

(6) Winston Churchill, letter to Sir Richard Hopkins (28th November, 1924)

(7) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 294

(8) Roy Jenkins, Churchill (2001) page 399

(9) Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (1991) page 469

(10) Roy Jenkins, Churchill (2001) page 401

(11) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 298

(12) Roy Jenkins, Churchill (2001) page 404

(13) Winston Churchill, letter to James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury (9th December, 1924)

(14) Winston Churchill, letter to James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury (27th December, 1924)

(15) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 304

(16) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (30th April, 1925)

(17) Thomas Jones, diary entry (17th May, 1925)

(18) Winston Churchill, letter to Arthur Steel-Maitland (19th September, 1925)

(19) Winston Churchill, letter to Stanley Baldwin (20th September, 1925)

(20) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 305

(21) Frederick A. Macquisten, speech in the House of Commons (6th March, 1925)

(22) Stanley Baldwin, speech in the House of Commons (6th March, 1925)

(23) A. J. P. Taylor, English History: 1914-1945 (1965) page 318

(24) Julian Symons, The General Strike (1957) page 226

(25) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 314

(26) The Daily Mail (28th April, 1928)

(27) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 314

(28) Millicent Fawcett, diary entry (2nd July 1928)

(29) Roy Jenkins, Baldwin (1987) page 107

(30) The Conservative Manifesto: Mr. Stanley Baldwin's Election Address (May, 1929)

(31) The Labour Manifesto: Labour's Appeal to the Nation (May, 1929)

(32) Roy Hattersley, David Lloyd George (2010) page 608

(33) Winston Churchill, letter to David Lloyd George (28th July, 1929)

(34) Brendan Bracken, letter to Lord Beaverbrook (14th January, 1931)

(35) Lord Beaverbrook, letter to Robert Borden (7th January, 1931)

(36) Anne Chisholm & Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: A Life (1992) page 289

(37) The Daily Express (5th, 10th, 11th and 12th December, 1920)

(38) George Ward Price, Sunday Dispatch (5th January, 1930)

(39) Anne Chisholm & Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: A Life (1992) page 292

(40) Lord Beaverbrook, letter to Sir Rennell Rodd (6th June, 1930)

(41) The Daily Mail (14th February, 1930)

(42) Robert Bruce Lockhart, diary entry (14th February, 1930)

(43) The Daily Express (18th, 19th, 20th and 26th February, 1930)

(44) Anne Chisholm & Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: A Life (1992) page 294

(45) Lord Beaverbrook, Politicians and the Press (1925) page 9

(46) Tom Driberg, Beaverbrook, A Study in Power and Frustration (1956) pages 206-207

(47) The Daily Express (7th May, 1930)

(48) Iain Macleod, Neville Chamberlain (1961) page 136

(49) Lord Beaverbrook, letter to Alfred Mond, 1st Lord Melchett (22nd September, 1930)

(50) Neville Chamberlain, diary entry (23rd February, 1931)

(51) Peter Neville, Neville Chamberlain (1992) page 51

(52) Robert Blake, Baldwin and the Right, included in John Raymond (editor), The Baldwin Age (1960) page 29

(53) Anne Chisholm & Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: A Life (1992) page 299

(54) Stanley Baldwin, letter to John C. Davidson (2nd November, 1930)

(55) A. J. P. Taylor, Beaverbrook (1972) page 299

(56) Lord Beaverbrook, letter to Richard Smeaton White (12th November 1930)

(57) Lord Beaverbrook, letter to Lord Rothermere (13th January, 1931)

(58) Lord Rothermere, letter to Lord Beaverbrook (14th January, 1931)

(59) A. J. P. Taylor, Beaverbrook (1972) page 304

(60) Anne Chisholm & Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: A Life (1992) page 303

(61) Robert Blake, Baldwin and the Right, included in John Raymond (editor), The Baldwin Age (1960) page 52

(62) John Charmley, Duff Copper (1986) page 64

(63) Jeremy Dobson, Why Do the People Hate Me So? (2010) page 182

(64) The Times (18th March, 1931)

(65) Anne Chisholm & Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: A Life (1992) page 306

(66) S. J. Taylor, The Great Outsiders: Northcliffe, Rothermere and the Daily Mail (1996) page 274

(67) Tom Johnson, speech in the House of Commons (8th September, 1931)

(68) Neville Chamberlain, speech in the House of Commons (19th April 1932)

(69) David Faber, Munich: The 1938 Appeasement Crisis (2008) pages 169-170

(70) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) pages 756-757

(71) The Economist (3rd February 1954)

Previous Posts

Stanley Baldwin and his failed attempt to modernise the Conservative Party (15th April, 2019)

The Delusions of Neville Chamberlain and Theresa May (26th February, 2019)

The statement signed by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Kathleen Kennedy Townsend (20th January, 2019)

Was Winston Churchill a supporter or an opponent of Fascism? (16th December, 2018)

Why Winston Churchill suffered a landslide defeat in 1945? (10th December, 2018)

The History of Freedom Speech in the UK (25th November, 2018)

Are we heading for a National government and a re-run of 1931? (19th November, 2018)

George Orwell in Spain (15th October, 2018)

Anti-Semitism in Britain today. Jeremy Corbyn and the Jewish Chronicle (23rd August, 2018)

Why was the anti-Nazi German, Gottfried von Cramm, banned from taking part at Wimbledon in 1939? (7th July, 2018)

What kind of society would we have if Evan Durbin had not died in 1948? (28th June, 2018)

The Politics of Immigration: 1945-2018 (21st May, 2018)

State Education in Crisis (27th May, 2018)

Why the decline in newspaper readership is good for democracy (18th April, 2018)

Anti-Semitism in the Labour Party (12th April, 2018)

George Osborne and the British Passport (24th March, 2018)

Boris Johnson and the 1936 Berlin Olympics (22nd March, 2018)

Donald Trump and the History of Tariffs in the United States (12th March, 2018)

Karen Horney: The Founder of Modern Feminism? (1st March, 2018)

The long record of The Daily Mail printing hate stories (19th February, 2018)

John Maynard Keynes, the Daily Mail and the Treaty of Versailles (25th January, 2018)

20 year anniversary of the Spartacus Educational website (2nd September, 2017)

The Hidden History of Ruskin College (17th August, 2017)

Underground child labour in the coal mining industry did not come to an end in 1842 (2nd August, 2017)

Raymond Asquith, killed in a war declared by his father (28th June, 2017)

History shows since it was established in 1896 the Daily Mail has been wrong about virtually every political issue. (4th June, 2017)

The House of Lords needs to be replaced with a House of the People (7th May, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Caroline Norton (28th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Mary Wollstonecraft (20th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Anne Knight (23rd February, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Elizabeth Heyrick (12th January, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons: Where are the Women? (28th December, 2016)

The Death of Liberalism: Charles and George Trevelyan (19th December, 2016)

Donald Trump and the Crisis in Capitalism (18th November, 2016)

Victor Grayson and the most surprising by-election result in British history (8th October, 2016)

Left-wing pressure groups in the Labour Party (25th September, 2016)

The Peasant's Revolt and the end of Feudalism (3rd September, 2016)

Leon Trotsky and Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party (15th August, 2016)

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of England (7th August, 2016)

The Media and Jeremy Corbyn (25th July, 2016)

Rupert Murdoch appoints a new prime minister (12th July, 2016)

George Orwell would have voted to leave the European Union (22nd June, 2016)

Is the European Union like the Roman Empire? (11th June, 2016)

Is it possible to be an objective history teacher? (18th May, 2016)

Women Levellers: The Campaign for Equality in the 1640s (12th May, 2016)

The Reichstag Fire was not a Nazi Conspiracy: Historians Interpreting the Past (12th April, 2016)

Why did Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst join the Conservative Party? (23rd March, 2016)

Mikhail Koltsov and Boris Efimov - Political Idealism and Survival (3rd March, 2016)

Why the name Spartacus Educational? (23rd February, 2016)

Right-wing infiltration of the BBC (1st February, 2016)

Bert Trautmann, a committed Nazi who became a British hero (13th January, 2016)

Frank Foley, a Christian worth remembering at Christmas (24th December, 2015)

How did governments react to the Jewish Migration Crisis in December, 1938? (17th December, 2015)

Does going to war help the careers of politicians? (2nd December, 2015)

Art and Politics: The Work of John Heartfield (18th November, 2015)

The People we should be remembering on Remembrance Sunday (7th November, 2015)

Why Suffragette is a reactionary movie (21st October, 2015)

Volkswagen and Nazi Germany (1st October, 2015)

David Cameron's Trade Union Act and fascism in Europe (23rd September, 2015)

The problems of appearing in a BBC documentary (17th September, 2015)

Mary Tudor, the first Queen of England (12th September, 2015)

Jeremy Corbyn, the new Harold Wilson? (5th September, 2015)

Anne Boleyn in the history classroom (29th August, 2015)

Why the BBC and the Daily Mail ran a false story on anti-fascist campaigner, Cedric Belfrage (22nd August, 2015)

Women and Politics during the Reign of Henry VIII (14th July, 2015)

The Politics of Austerity (16th June, 2015)

Was Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, murdered? (31st May, 2015)

The long history of the Daily Mail campaigning against the interests of working people (7th May, 2015)

Nigel Farage would have been hung, drawn and quartered if he lived during the reign of Henry VIII (5th May, 2015)

Was social mobility greater under Henry VIII than it is under David Cameron? (29th April, 2015)

Why it is important to study the life and death of Margaret Cheyney in the history classroom (15th April, 2015)

Is Sir Thomas More one of the 10 worst Britons in History? (6th March, 2015)

Was Henry VIII as bad as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin? (12th February, 2015)

The History of Freedom of Speech (13th January, 2015)

The Christmas Truce Football Game in 1914 (24th December, 2014)

The Anglocentric and Sexist misrepresentation of historical facts in The Imitation Game (2nd December, 2014)

The Secret Files of James Jesus Angleton (12th November, 2014)

Ben Bradlee and the Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer (29th October, 2014)

Yuri Nosenko and the Warren Report (15th October, 2014)

The KGB and Martin Luther King (2nd October, 2014)

The Death of Tomás Harris (24th September, 2014)

Simulations in the Classroom (1st September, 2014)

The KGB and the JFK Assassination (21st August, 2014)

West Ham United and the First World War (4th August, 2014)

The First World War and the War Propaganda Bureau (28th July, 2014)

Interpretations in History (8th July, 2014)

Alger Hiss was not framed by the FBI (17th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: Part 2 (14th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: The CIA and Search-Engine Results (10th June, 2014)

The Student as Teacher (7th June, 2014)

Is Wikipedia under the control of political extremists? (23rd May, 2014)

Why MI5 did not want you to know about Ernest Holloway Oldham (6th May, 2014)

The Strange Death of Lev Sedov (16th April, 2014)

Why we will never discover who killed John F. Kennedy (27th March, 2014)

The KGB planned to groom Michael Straight to become President of the United States (20th March, 2014)

The Allied Plot to Kill Lenin (7th March, 2014)

Was Rasputin murdered by MI6? (24th February 2014)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Weapons (11th February, 2014)

Pete Seeger and the Media (1st February 2014)

Should history teachers use Blackadder in the classroom? (15th January 2014)

Why did the intelligence services murder Dr. Stephen Ward? (8th January 2014)

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave (4th January 2014)

The Angel of Auschwitz (6th December 2013)

The Death of John F. Kennedy (23rd November 2013)

Adolf Hitler and Women (22nd November 2013)

New Evidence in the Geli Raubal Case (10th November 2013)

Murder Cases in the Classroom (6th November 2013)

Major Truman Smith and the Funding of Adolf Hitler (4th November 2013)

Unity Mitford and Adolf Hitler (30th October 2013)

Claud Cockburn and his fight against Appeasement (26th October 2013)

The Strange Case of William Wiseman (21st October 2013)

Robert Vansittart's Spy Network (17th October 2013)

British Newspaper Reporting of Appeasement and Nazi Germany (14th October 2013)

Paul Dacre, The Daily Mail and Fascism (12th October 2013)

Wallis Simpson and Nazi Germany (11th October 2013)

The Activities of MI5 (9th October 2013)

The Right Club and the Second World War (6th October 2013)

What did Paul Dacre's father do in the war? (4th October 2013)

Ralph Miliband and Lord Rothermere (2nd October 2013)