Spartacus Blog

Does going to war help the careers of politicians?

Wednesday, 2nd December, 2015

Denis Healey, was interviewed by the BBC just a few weeks before he died. The 98-year-old veteran politician, was asked by Lewis Goodall how he wanted to be remembered. Healey replied that it was the way he dealt with the situation in Borneo when he was Secretary of State for Defence (1964-1970). He said he resisted demands to bomb the communist insurgents in the country. Healey argued that this would have led to greater opposition to British rule. He proudly pointed out that the situation was solved with less than hundred people being killed.

Healey said his decision was largely influenced by his experiences during the Second World War. Serving with the Royal Engineers, he saw action in the North African campaign, the Allied invasion of Sicily and the Italian campaign, and was the military landing officer for the British assault brigade at Anzio. Healey witnessed first hand what it was like to kill fellow human beings. It has been argued that the Iraq War may never have happened if Tony Blair and George Bush had served in the armed forces during a war. The prime minister, with the most military experience, Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, once said: “Next to a battle lost, the greatest misery is a battle gained.”

My own views on military adventures are also influenced by personal circumstances. My grandfather, John Simkin, was killed on the Western Front during the First World War. My father, John Simkin, did survive the Second World War, but he never recovered the psychological damage of having to kill people during the conflict.

As a ten-year-old I was made a school prefect. I could not wait to get home to tell my dad. Much to my surprise, he gave me a lecture of the dangers of authority. He did not quote Oscar Wilde, but if he knew it I am sure he would have done: "Disobedience in the eyes of anyone who has read history, is man’s original virtue. It is through disobedience that progress has been made, through disobedience and rebellion."

My father was killed shortly afterwards and this discussion is the only one I remember. Officially, he died in a road accident but my mother, Muriel Simkin, told me much later that he was suffering from depression and that she suspected he had committed suicide. She claims that he had never fully recovered from his war experiences. As we discovered with the Vietnam War, soldiers don't only die on the battlefield.

One would like to think that people living in a civilized society, would not need this kind of personal experience, to make sensible decisions about having to deal with political decisions that involve the killing of fellow human beings. They always justify by comparing the latest dictator they are dealing with to some historical figure, usually Adolf Hitler. That negotiations, or as they like to portray it, appeasement, always leads to more drawn-out wars in the future.

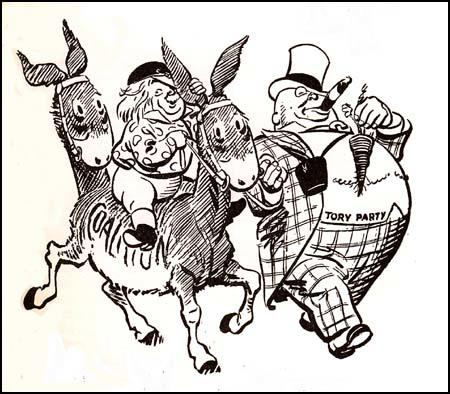

David Cameron might well think that the bombing of Daesh in Syria is a good career move. It might also explain Hilary Benn decision to support the government on this matter. The argument goes that he will be the right-wing candidate to take over when Jeremy Corbyn is overthrown. A look at history shows that the decision to go to war is usually very harmful to a politician's long-term career.

Those who favour the use of military adventures to solve political problems often use the example of Margaret Thatcher and the Falklands War in 1982. At the Conservative Party conference in October, 1981, Thatcher was behind Michael Foot in the polls and there was talk of her being ousted by the "wets". By June 1982, after the recapture of the Falklands, 59% were satisfied with her performance.

Thatcher was undoubtedly right that the public will get behind you at the beginning of a war. Especially if it brings back memories of the days when the British military forces could give small countries a beating. Thatcher also calculated that the war, given the circumstances of the time, would be short and successful. The general public probably did think the war was worth fighting and did not have too much sympathy for the 649 Argentineans soldiers who were killed. However, I am not sure the relatives of the 255 British servicemen who died during the war would have supported her "rejoice" proclamation on 25th April 1982.

David Cameron of course has no excuses for his appalling decision to bomb Syria. Recent military adventures in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya have also proved disastrous and are still no where near reaching their original objectives. However, other wars since the end of the 19th century will provide little comfort for ambitious politicians.

The outbreak of the First World War caused great conflict in the governing Liberal Party. Four senior members of the government, David Lloyd George, Charles Trevelyan, John Burns, and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, to change his mind.

Most of the leaders of the Labour Party, including Ramsay MacDonald, Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett, were also opposed to the war. Others in the party such as Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, Will Thorne and Ben Tillett believed that the movement should give total support to the war effort.

On 5th August, 1914, the parliamentary party voted to support the government's request for war credits of £100,000,000. MacDonald immediately resigned the chairmanship of the party. Five days later MacDonald had a meeting with Philip Morrel, Norman Angell, E. D. Morel, Charles Trevelyan and Arthur Ponsonby and formed an anti-war group called the Union of Democratic Control.

Ramsay MacDonald suffered the same attacks from the conservative controlled press that was far worse than Jeremy Corbyn had to endure. On 1st October 1914, The Times published a leading article entitled Helping the Enemy, in which it wrote that "no paid agent of Germany had served her better" that MacDonald had done. The newspaper also included an article by Ignatius Valentine Chirol, who argued: "We may be rightly proud of the tolerance we display towards even the most extreme licence of speech in ordinary times... Mr. MacDonald' s case is a very different one. In time of actual war... Mr. MacDonald has sought to besmirch the reputation of his country by openly charging with disgraceful duplicity the Ministers who are its chosen representatives, and he has helped the enemy State ... Such action oversteps the bounds of even the most excessive toleration, and cannot be properly or safely disregarded by the British Government or the British people."

Horatio Bottomley, argued in the John Bull Magazine that Ramsay MacDonald and Keir Hardie, were the leaders of a "pro-German Campaign". On 19th June 1915 the magazine claimed that MacDonald was a traitor and that: "We demand his trial by Court Martial, his condemnation as an aider and abetter of the King's enemies, and that he be taken to the Tower and shot at dawn."

On 4th September, 1915, the magazine published an article which made an attack on his background. "We have remained silent with regard to certain facts which have been in our possession for a long time. First of all, we knew that this man was living under an adopted name - and that he was registered as James MacDonald Ramsay - and that, therefore, he had obtained admission to the House of Commons in false colours, and was probably liable to heavy penalties to have his election declared void. But to have disclosed this state of things would have imposed upon us a very painful and unsavory duty. We should have been compelled to produce the man's birth certificate. And that would have revealed what today we are justified in revealing - for the reason we will state in a moment... it would have revealed him as the illegitimate son of a Scotch servant girl!"

However, public opinion began to change when the government failed to provided the promised quick victory. Herbert Asquith came under pressure, from the tabloid press, who had advocated the war, to resign. The consequences of the Battle of the Somme put further pressure on Asquith. Colin Matthew has commented: "The huge casualties of the Somme implied a further drain on manpower and further problems for an economy now struggling to meet the demands made of it."

David Lloyd George saw this as an opportunity to oust his leader. He joined forces with Max Aitken, Andrew Bonar Law and Edward Carson, to draft a statement addressed to Asquith, proposing a war council triumvirate and the Prime Minister as overlord. On 25th November, Bonar Law took the proposal to Asquith, who agreed to think it over. The next day he rejected it. This information was leaked to the press by Carson. On 4th December The Times used these details of the War Committee to make a strong attack on Asquith. The following day he resigned from office.

Lloyd George's decision to join the Conservatives in removing Asquith in 1916 split the Liberal Party. In the 1918 General Election, many Liberals supported candidates who remained loyal to Asquith. Lloyd George's Coalition group won 459 seats and had a large majority over the Labour Party and Liberals who had supported Asquith.

During the 1918 election campaign, Lloyd George promised comprehensive reforms to deal with education, housing, health and transport. However, he was now a prisoner of the Conservative Party who had no desire to introduce these progressive reforms. Lloyd George endured three years of frustration before he was ousted from power by the Conservative members of his cabinet.

Did the First World War help or damage Lloyd George's political career? As a result of the progressive legislation introduced by the government between 1906-1914, the Liberal Party was the largest party in the House of Commons. Lloyd George was the most popular of all their MPs as a result of his time as the Chancellor of the Exchequer. He was especially liked for the People's Budget in 1909, which introduced new progressive tax system. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new super tax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5,000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property.

Lloyd George's was seen as the leader of the left of the party and the best man to deal with the emerging Labour Party. It was only a matter of time before he became prime minister. It was the war that damaged his reputation as the man of the people and lost him the support of fellow party members. Over the next few years he drifted to the far-right and in a speech he made in 1933 he gave his support to Adolf Hitler: "If the Powers succeed in overthrowing Nazism in Germany, what would follow? Not a Conservative, Socialist or Liberal regime, but extreme Communism. Surely that could not be their objective. A Communist Germany would be infinitely more formidable than a Communist Russia.”

Those politicians that opposed the First World War did very badly in the 1918 General Election. Ramsay MacDonald was the Labour candidate for Leicester East. The coalitionist candidate, Gordon Hewart, concentrated on MacDonald's opposition to the war. He argued that MacDonald had "put an odious stain and stima upon the fair name of Leicester". He went on to say that this was not "an indelible stain" and "the citizens of Leicester now had the opportunity of wiping it away and of meting out to its author his well-merited reward." MacDonald lost the election by 15,000 votes.

Other opponents of the war such as Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett, also lost their seats. However, over the next few years people became aware that the politicians had completely failed to keep the promises about creating a "land fit for heroes" and following the 1923 General Election, Ramsay MacDonald became prime minister and Snowden, Lansbury and Jowett were cabinet ministers. So also was Charles Trevelyan, who had resigned from the cabinet over the decision to enter the war.

Neville Chamberlain did what he could to avoid war and historians have argued that he became the most popular prime minister in our history after meeting Adolf Hitler and signing the the Munich Agreement on 29th September, 1938. It has to be remembered that the government's appeasement policy was enthusiastically supported by the majority of the population during the 1930s. This was largely a reaction to the stories brought back from the Western Front of the horrors of modern warfare.

The following day, Edward Murrow, the American broadcaster working for Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) reported: "Thousands of people are standing in Whitehall and lining Downing Street, waiting to greet the Prime Minister upon his return from Munich. Certain afternoon papers speculate concerning the possibility of the Prime Minister receiving a knighthood while in office, something that has happened only twice before in British history. Others say that he should be the next recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize."

On 15th March 1930, Hitler's troops occupied Prague and announced the annexation of the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia. Three days later, Chamberlain finally acknowledged to the cabinet that: "No reliance could be placed on any of the assurances given by the Nazi leaders." As Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) has pointed out: "a conclusion which the Security Service had put formally to the cabinet secretary almost three years earlier." Unfortunately for Chamberlain, he had preferred to listen to King George VI than MI5 (Edward was not the only member of the royal family who was sympathetic to fascism).

It is worth pointing out that Chamberlain remained popular even after the outbreak of the Second World War. In September, 1939, public opinion polls showed that Chamberlain's popularity was 55 per cent. By December this had increased to 68 per cent. There is no doubt that prime minister always benefit from a declaration of war. No doubt, David Cameron's personal ratings will improve after today's vote to bomb Syria.

In the early months of 1940 Chamberlain remained popular. The public were probably hoping that he was secretly negotiating a peace deal with Hitler. It was only when the German Army headed west that Chamberlain came under pressure. On 7th May, Leo Amery, the Conservative MP, argued in the House of Commons: "Just as our peace-time system is unsuitable for war conditions, so does it tend to breed peace-time statesmen who are not too well fitted for the conduct of war. Facility in debate, ability to state a case, caution in advancing an unpopular view, compromise and procrastination are the natural qualities - I might almost say, virtues - of a political leader in time of peace. They are fatal qualities in war. Vision, daring, swiftness and consistency of decision are the very essence of victory." Looking at Chamberlain he then went onto quote what Oliver Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go." (Ironically, Leo Amery's son, John Amery, was hanged as a fascist supporter on 19th December, 1945.)

King George VI had not given up on a negotiated peace agreement with Hitler and put forward the suggestion that arch-appeaser, Lord Halifax, should become prime minister. However, Clement Attlee, and other members of the Labour Party, in the coalition government, refused to accept Halifax and Winston Churchill became the new prime minister.

It is no doubt that without the Second World War Churchill would never had got the top job. During the Great Depression he developed a reputation as a right-wing extremist and he remained outside the cabinet until Chamberlain appointed him as First Lord of the Admiralty as part of his National Government.

Nor did becoming prime minister make him a popular political figure. It is reported that he was roundly booed when he visited the areas bombed by the Luftwaffe. In 1940 it looked like we had no chance of winning the war and most people wanted us to do a deal with Hitler. Churchill agreed but negotiations came to an end when Hitler refused to let Britain keep her empire.

There is very little evidence that the war made Churchill a popular leader. This view is supported by the 1945 General Election that followed the war. The Labour Party, led by Clement Attlee, had a landslide victory. There are several reasons for Churchill's defeat, but one of the most important factors was that he was seen as a war-monger and if he remained as prime minister he might have wanted to take on the Soviet Union.

I am not suggesting that by taking us into war David Cameron will lose office. In fact, I predict that over the next 18 months he will have a significant lead in the polls over Jeremy Corbyn. But that will gradually change if we make no progress in defeating Daesh and that we are the victims of several terrorist attacks. Cameron is on record that he will not be prime minister by the next election. It could be that this disastrous bombing policy will pave the way for David Davis to become the next leader of the Conservative Party.

Previous Posts

Does going to war help the careers of politicians? (2nd December, 2015)

Art and Politics: The Work of John Heartfield (18th November, 2015)

The People we should be remembering on Remembrance Sunday (7th November, 2015)

Why Suffragette is a reactionary movie (21st October, 2015)

Volkswagen and Nazi Germany (1st October, 2015)

David Cameron's Trade Union Act and fascism in Europe (23rd September, 2015)

The problems of appearing in a BBC documentary (17th September, 2015)

Mary Tudor, the first Queen of England (12th September, 2015)

Jeremy Corbyn, the new Harold Wilson? (5th September, 2015)

Anne Boleyn in the history classroom (29th August, 2015)

Why the BBC and the Daily Mail ran a false story on anti-fascist campaigner, Cedric Belfrage (22nd August, 2015)

Women and Politics during the Reign of Henry VIII (14th July, 2015)

The Politics of Austerity (16th June, 2015)

Was Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, murdered? (31st May, 2015)

The long history of the Daily Mail campaigning against the interests of working people (7th May, 2015)

Nigel Farage would have been hung, drawn and quartered if he lived during the reign of Henry VIII (5th May, 2015)

Was social mobility greater under Henry VIII than it is under David Cameron? (29th April, 2015)

Why it is important to study the life and death of Margaret Cheyney in the history classroom (15th April, 2015)

Is Sir Thomas More one of the 10 worst Britons in History? (6th March, 2015)

Was Henry VIII as bad as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin? (12th February, 2015)

The History of Freedom of Speech (13th January, 2015)

The Christmas Truce Football Game in 1914 (24th December, 2014)

The Anglocentric and Sexist misrepresentation of historical facts in The Imitation Game (2nd December, 2014)

The Secret Files of James Jesus Angleton (12th November, 2014)

Ben Bradlee and the Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer (29th October, 2014)

Yuri Nosenko and the Warren Report (15th October, 2014)

The KGB and Martin Luther King (2nd October, 2014)

The Death of Tomás Harris (24th September, 2014)

Simulations in the Classroom (1st September, 2014)

The KGB and the JFK Assassination (21st August, 2014)

West Ham United and the First World War (4th August, 2014)

The First World War and the War Propaganda Bureau (28th July, 2014)

Interpretations in History (8th July, 2014)

Alger Hiss was not framed by the FBI (17th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: Part 2 (14th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: The CIA and Search-Engine Results (10th June, 2014)

The Student as Teacher (7th June, 2014)

Is Wikipedia under the control of political extremists? (23rd May, 2014)

Why MI5 did not want you to know about Ernest Holloway Oldham (6th May, 2014)

The Strange Death of Lev Sedov (16th April, 2014)

Why we will never discover who killed John F. Kennedy (27th March, 2014)

The KGB planned to groom Michael Straight to become President of the United States (20th March, 2014)

The Allied Plot to Kill Lenin (7th March, 2014)

Was Rasputin murdered by MI6? (24th February 2014)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Weapons (11th February, 2014)

Pete Seeger and the Media (1st February 2014)

Should history teachers use Blackadder in the classroom? (15th January 2014)

Why did the intelligence services murder Dr. Stephen Ward? (8th January 2014)

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave (4th January 2014)

The Angel of Auschwitz (6th December 2013)

The Death of John F. Kennedy (23rd November 2013)

Adolf Hitler and Women (22nd November 2013)

New Evidence in the Geli Raubal Case (10th November 2013)

Murder Cases in the Classroom (6th November 2013)

Major Truman Smith and the Funding of Adolf Hitler (4th November 2013)

Unity Mitford and Adolf Hitler (30th October 2013)

Claud Cockburn and his fight against Appeasement (26th October 2013)

The Strange Case of William Wiseman (21st October 2013)

Robert Vansittart's Spy Network (17th October 2013)

British Newspaper Reporting of Appeasement and Nazi Germany (14th October 2013)

Paul Dacre, The Daily Mail and Fascism (12th October 2013)

Wallis Simpson and Nazi Germany (11th October 2013)

The Activities of MI5 (9th October 2013)

The Right Club and the Second World War (6th October 2013)

What did Paul Dacre's father do in the war? (4th October 2013)

Ralph Miliband and Lord Rothermere (2nd October 2013)