London Society for Women's Suffrage

In May 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. It's founder members were the same women who formed the Langham Place Group and had been involved in the married women's property agitation and who had struggled to open local education examinations to girls. (1)

Membership was by personal invitation. The secretary, Emily Davies, brought together women "having more or less common interests and aims". Many were already friends, or were relatives of members. Others had been involved in the English Woman's Journal and had supported the campaign to open the Cambridge University local examinations to girls in 1864. Some met and shared ideas at the society for the first time. (2)

The Kensington Society had about fifty members, including Barbara Bodichon (artist), Jessie Boucherett (writer), Emily Davies (educationalist), Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Frances Power Cobbe (journalist), Anne Clough (educationalist), Alice Westlake (artist), Helen Taylor (educationalist), Elizabeth Garrett (medical student), Sophia Jex-Blake (medical student), Bessie Rayner Parkes (writer) and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy (headmistress). (3)

Members of the Kensington Society were united by the opportunity to debate issues in a private, yet formal, setting. The women wanted practice in formal debating to build confidence for future public speaking. Some of the subjects discussed included: "What are the tests of originality?", "Is it desirable to employ emulation as a stimulus to education?" and "What form of government is most favourable to women?" In November 1865 the question was debated: "Is the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" (4)

John Stuart Mill was invited by the Liberal Party to stand for the House of Commons in the 1865 General Election for Westminster. The Kensington Society saw this as an opportunity to promote the campaign for women's suffrage. In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Mill's step-daughter, Helen Taylor: "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time... Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately." (5)

Helen Taylor stated that "If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up" her father would be willing to present it to Parliament." Two days later Barbara Bodichon replied that a small group including herself, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Elizabeth Garrett and Jessie Boucherett, had already started collecting signatures. (6) On receiving Taylor's draft petition, Bodichon commented it was too long and "it would be better to make it as short as possible and to state as few reasons as possible for what we want, everyone has something to say against the reasons." (7)

In less than a month the Kensington Society collected nearly 1,500 signatures (one important member, Dorothea Beale, refused to sign the petition. Helen replied when it was delivered: "My father will present the petition tomorrow (if that is still the wish of the ladies) and it should be sent to the House of Commons to arrive there before two p.m. tomorrow, Thursday June 7th directed to Mr Mill, and petition written on it. It is indeed a wonderful success. It does honour to the energy of those who have worked for it and promises well for the prospects of any future plan for furthering the same objects." (8)

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment to the 1867 Reform Act was defeated by 196 votes to 73. William Gladstone, was one of those who voted against the amendment. (9)

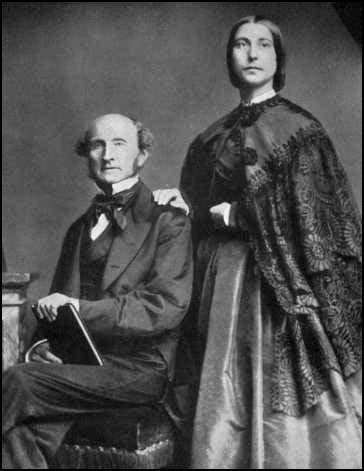

hiding first women’s suffrage petition under an apple-woman’s stall in Westminster Hall

until John Stuart Mill came to collect it.

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to dissolve the organisation and to establish the London Society for Women's Suffrage in 1867 with the sole purpose of campaigning for women's suffrage. (10)

Clementia Taylor was the driving force behind the formation of the London Society for Women's Suffrage. From the outset it was intended that this new society in London was to be part of a federated scheme. Taylor wrote that she was willing "to undertake the secretary-ship of the London Central Committee the centres all to be affiliated together and in constant correspondence with each other so that no work shall be repeated. I think different centres will be necessary for local actions - but no centre to take any important step without reference to all the other centres." (11)

It was Clementia Taylor who suggested the name "The London Woman Suffrage Society" and she also argued that it should cooperate closely with the recently formed Manchester Society for Suffrage. (12) The first committee of the society included Clementia Taylor, Frances Power Cobbe, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Katharine Hare and Margaret Bright Lucas. Other members included Helen Taylor, Lydia Becker, Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Rhoda Garrett, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Louisa Garrett Smith, Priscilla McLaren, Elizabeth Garrett, Alice Westlake, Caroline Ashurst Biggs, Catherine Winkworth and Kate Amberley. (13) The undermentioned have among others, joined the general committee: Florence Nightingale, John Russell, John Bowring, Robert Austruther, George Hadfield, George Croom Robertson and Edmund Beales joined the general committee of the London Society for Women's Suffrage. (14)

Clementia Taylor took the main role in developing the strategy for the London Society for Women's Suffrage: "Our present course of action is the dissemination of information throughout the kingdom and it seems to me, we cannot apply our pounds to better purpose than by the publication of good papers." (15) This included Helen Taylor's pamphlet's The Claims of Englishwomen to the Suffrage Constitutionally Considered. (16)

Caroline Ashurst Biggs was made assistant secretary of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage (LNSWS), alongside Clementia Taylor, in 1867, a post which she held until 1871. According to Helen Blackburn, the author of Women's Suffrage: A Record of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the British Isles (1902): "Her (Caroline Biggs) ready pen, methodical work and untiring industry soon proved her an invaluable ally" (17)

It was decided to allow men to play an active role in the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Rachael Strachey pointed out: "At that date it was usual, when men and women were on a committee together, for the men to do all the talking, but in these early suffrage groups neither the men nor the women were of that kind. They practised, as well as believed in, equality, to the great advantage of their cause." (18)

It was reported that at a meeting of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage that took place at the Stamford Street Chapel on 6th April 1868. Henry Fawcett occupied the chair, and Thomas Hughes, M.P. and James Heywood, made speeches. "The chairman opened the proceedings by contrasting the condition of women in the various civilised countries of the earth. He combated the argument that women were intellectually inferior to men, and contended that, with equal opportunities, they had generally proved themselves on an equality with men. He entirely concurred in the object of the meeting." Thomas Hughes "spoke at some length respecting the present state of the laws affecting married women and the rights of property, which he contended, were in a most unfair and unsatisfactory state. He thought there was no likelihood of the law in this respect being improved until women had a direct influence in the representation." (19)

Another meeting of the London Society for Women's Suffrage was held in the Gallery of the Architectural Society in Conduit Street on 17th July 1869. The chair was taken by Clementia Taylor and the audience heard for the first time women speak from a London platform in the furtherance of their cause. The following year on 26th March 1870, another meeting was held, this time in the Hanover Square Rooms, again with Taylor in the chair. Among the speakers were Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Katherine Hare, Harriet Grote, Caroline Ashurst Biggs, Helen Taylor, John Stuart Mill and Charles Wentworth Dilke. (20)

Catherine Winkworth wrote later: "Miss Helen Taylor made a most remarkable speech. She is a slight young woman, with long, thin, delicate features, clear dark eyes and dark hair, which she wears in long bands on her cheeks, fashionably dressed in slight mourning; speaks off the platform in a high, thin voice, very shyly with an embarrassed air; on the platform she was really eloquent." (21) Another observer, Kate Russell, Lady Amberley, commented that it was "a long and much studied speech; it was good but too like acting." (22)

In November 1871, Jacob Bright suggested at the annual general meeting of the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage that greater pressure could be applied on members of the House of Commons by establishing a standing central committee in London representing all the suffrage societies. John Stuart Mill argued against having two organisations in favour of women's suffrage but Clementia Taylor agreed with Bright and as a result resigned from the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Her friend, George Eliot, wrote to her: "Welcome back from your absorption in the franchise! Somebody else ought to have your share of work now, and you ought to rest." (23)

The death of John Stuart Mill in 1873, was a terrible blow to the women's suffrage movement. Jacob Bright now became the main spokesman in the House of Commons for the London Society for Women's Suffrage. In 1878 Bright fell ill, and retired from Parliament, and the leadership passed to Leonard Courtney. As Rachael Strachey pointed out in The Cause: A Short History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain (1928): "Mr Courtney's task was hard. He was, however, a young man full of hope and courage; and he fairly forced the warring committees to amalgamate, and to present a united front to the enemy." (24)

In 1886, women in favour of women's suffrage in the party decided to form the Women's Liberal Federation. This group had no success in persuading the male leadership of the Liberal Party in parliament to support legislation. Suffragists within the party doubted the commitment of the leader of the organisation, Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle, to the cause and in 1887 a group of women, including Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Eva Maclaren, Frances Balfour and Marie Corbett, formed the Liberal Women's Suffrage Society. (25)

By the 1890s there were seventeen individual groups that were advocating women's suffrage. This included the London Society for Women's Suffrage, Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage, Liberal Women's Suffrage Society and the Central Committee for Women's Suffrage. On 14th October 1897, these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Millicent Garrett Fawcett was elected as president. Other members of the executive committee included Marie Corbett, Chrystal Macmillan, Maude Royden and Eleanor Rathbone. (26)

Primary Sources

(1) Alice Westlake, letter to Helen Taylor (20th March, 1865)

There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse.

(2) Barbara Bodichon, letter to Helen Taylor (9th May, 1866)

I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time. I have only just arrived in London from Algiers but I have already seen many ladies who are willing to take some steps for this cause. Miss Boucherett who is here puts down £25 at once for expenses. I shall be every day this week at this office at 3 p.m. Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately.

(3) Helen Taylor, letter to Barbara Bodichon (9th May, 1866)

It seems to me that while a Reform Bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from different classes - asking for representation or protesting against disenfranchisement should say so, and that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so, and that women not saying so now will be used against them in the future and delay the time of their enfranchisement.... I think the most important thing is to make a demand and commence the first humble beginnings of an agitation for which reasons can be given that are in harmony with the political ideas of English people in general. No idea is so universally accepted and acceptable in England as that taxation and representation ought to go together, and people in general will be much more willing to listen to the assertion that single women and widows of property have been overlooked and left out from the privileges to which their property entitles them, than to the much more startling general proposition that sex is not a proper ground for distinction in political rights...

We should only be petitioning for the omission of the words male and men from the present act... If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up my father will gladly undertake to present it and will consider whether it might be made the occasion for anything further. He could at least move for a return of the number of householders disqualified on account of sex, which could be useful to us in many ways if it could be got. I shall be very glad to subscribe £20 towards expenses.

(5) Louisa Garrett Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1939)

John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… On 7th June 1866 the petition with 1,500 signatures was taken to the House of Commons. It was in the name of Barbara Bodichon and others, but some of the active promoters could not come and the honour of presenting it fell to Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett…. Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again.

(6) Clementia Taylor, letter to Helen Taylor (29th October, 1866)

I read.... your objection to a mixed committee of men and women. Now my experience bears testimony to the practical benefit resulting from the combined efforts of men and women - we gain advantage from the more logical and from the more practical qualities of men - and men gain from women more earnestness of purpose - more subtle views of questions - I believe so strongly in the reciprocal benefit of both I would from the earliest age have boys and girls educated together - associated together in all the higher purposes of life and believe that morally as well as mentally the word would gain much - but to our committee I deeply grieve that we are not at one upon this question, it was not without due thought and consideration that we determined upon the mixed working committee... I have been on committees formed of women only and upon more - men and women together - the latter certainly acted more effectively and I believe that the committees of men only would be less effective than if women were associated with them.

(7) Clementia Taylor, letter to Helen Taylor (4th March, 1867)

There should be a large meeting of the earnest friends of the cause to decide upon future work, organisation etc. and form a new committee - have a paid Secretary - officials - such a Committee as you will be induced to join - and in which I shall not feel myself as a Pariah.

(8) Clementia Taylor, letter to Helen Taylor (15th July, 1867)

Our present course of action is the dissemination of information throughout the kingdom and it seems to me, we cannot apply our pounds to better purpose than by the publication of good papers.