Jessie Boucherett

Emilia (Jessie) Boucherett, the youngest child of Ayscoghe Boucherett and Louisa Minchin Boucherett, was born at North Willingham, near Market Rasen, on 29th November 1825. Her father had been High Sheriff of Lincolnshire and was a wealthy landowner. (1)

Jessie's mother was a cousin of Florence Nightingale and Louisa Knightley. She spent two years, at Avonbank, the school in Warwickshire which was attended by Elizabeth Gaskell and where the curriculum included the works of women writers of the day. (2)

Jessie Boucherett was inspired to help women find employment after reading an article entitled "On Female Industry" by Harriet Martineau in the Edinburgh Review about the subject. In the article Martineau suggested: "Out of six millions of women above twenty years of age, in Great Britian, exclusive of Ireland, and of course of the Colonies, no less than half are industrial in their mode of life. More than a third, more than two millions, are independent in their industry, are self-supporting, like men." (3)

It has been argued that the effect of this article on Boucherett was life-changing. She wrote later that "at once [she] resolved to make it the business of her life to remedy or at least to alleviate the evil by helping self-dependent women, not with gifts of money, but with encouragement and training for employments suited to their capabilities." (4)

Jessie Boucherett and Langham Place Group

According to Helen Blackburn Boucherett purchased a copy of the The English Woman's Journal at a railway bookstall. She was so impressed with the content of the magazine she came to London in June 1859 to meet the editors, Elizabeth Rayner Parkes and Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon. (5) Boucherett "described how she came expecting to see some dowdy old lady, and found herself in the midst of young women who were well dressed, beautiful and gay." (6)

Boucherett now joined the Langham Place Group. Other members included Louisa Garrett Smith, Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies, Helen Blackburn, Sophia Jex-Blake, Alice Westlake, Adelaide Procter, Frances Power Cobbe and Emily Faithfull. These women were therefore "at the core of the emerging mid-Victorian women's movement". (7) The group played an important role in campaigning for women to become doctors. They arranged for Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor, to give a lecture entitled, "Medicine as a Profession for the Ladies". In 1862 they formed a committee to campaign for women's entry for university examinations, initially in support of Elizabeth Garrett, in her application to matriculate at London University. (8)

As her biographer, Linda Walker, has pointed out: " It was here that many ideas concerning women's present and future role in society began to germinate, and what came to be referred to as the Langham Place circle became the centre for women's rights activities over the next few years. Supported by her private income and surrounded by like-minded new friends, Boucherett subsequently devoted much of her life to the cause of women's emancipation." (9)

Society for Promoting the Employment of Women

Jessie Boucherett suggested that the group should help promote women's employment. As a result the Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women (SPEW) was established in June 1859 in London. They enlisted the support of Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Earl of Shaftesbury, who became the society's first president, and other members of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science. Another important member was the Christian Socialist and legal scholar, John Westlake. (10)

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women was based initially at 19 Langham Place. They began a law copying office, a school to train women as bookkeepers, clerks, and cashiers, and a register of employment. While such measures could clearly help only a few women of the middling classes, the pioneers regarded their innovations as experiments which prepared the ground for future change. (11)

After a visit to the London office Emily Davies established the Northumberland and Durham Branch of the SPEW. However, not all the members of the Langham Place Group were in total agreement about the employment of women in industry. Elizabeth Rayner Parkes condemned the work of married women outside the home, though Boucherett and Faithfull argued that "every woman should be free to support herself by the use of whatever faculties God has given her, without obstruction by prejudice or legislation". (12)

As Jane Rendall pointed out: "These liberal feminists recognized a potential conflict with orthodox political economy, often invoked against women's work as depressing the wages of men in free competition. Some, like Boucherett, were prepared to face the consequences of a free market in labour. Parkes and others suggested ways in which association and co-operation among women might moderate the harshness of the free market, though some proposals looked more like philanthropy than co-operation." (13)

The work of the Langham Place group was given added publicity by the success of two papers given at the conference of the Social Science Association held in Bradford in October 1859. Elizabeth Rayner Parkes read a paper, to which Barbara Leigh Smith contributed, on "The Market for Educated Female Labour" and Jessie Boucherett delivered "The Industrial Employments of Women". (14) Boucherett wrote to Smith claiming: "The whole kingdom is ringing with our Bradford Paper, and subscriptions pouring in at the EWJ (English Woman's Journal) office... What a crown to our long struggle begun 10 years ago.... It is a long struggle which is beginning to tell; and the having an organisation in which to receive the Public Interest." (15)

Harriet Martineau wrote an article about Parkes's speech in The Daily News. "Miss Parkes's paper was abundantly clear and definite. She tells us the truth that a multitude of the daughters of middle-class men are neither educated nor provided for like their brothers; and that if they do not marry, they must work (unprepared by education as they are) or starve. The terms demanded on behalf of women are that parents shall either educate their daughters so as to fit them for independent industry; or lay by a provision for them; or insure their own lives for the benefit of their daughters in the day which will make them fatherless. This is very simple and clear. It is also very interesting; and, as a natural consequence, we hear of sympathy, in the form of advice and suggestions, in all directions; and of various establishments, existing or proposed, with more or less of the charitable element involved for the relief and aid of industrial women of the middle class. (16)

On 1st October 1860 Jessie Boucherett made a speech in Glasgow: "She dealt with three major areas: Jessie Boucherett's work in training young women to take situations as cashiers and clerks, Isa Craig's work in training women as telegraph clerks, and Maria Rye's law copying office where women earned a living by making accurate copies of legal documents." In just over a year SPEW managed to find permanent jobs for up to seventy-five women a year and temporary jobs for up to a hundred. (17)

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women gained support for its efforts from The English Woman's Journal. The journal was published by a limited company. The main shareholders were Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon and Emily Faithfull. The wealthy industrialist, Samuel Courtauld, a Unitarian, also invested in the venture. The editor was Bessie Rayner Parkes. (18)

The journal was published monthly and cost 1 shilling. It was used to discuss female employment and equality issues concerning, in particular, manual or intellectual industrial employment, expansion of employment opportunities, and the reform of laws pertaining to the sexes. The offices in Langham Place became a centre for a wide variety of feminist enterprises. These included a women's reading-room and dining club, and offices for the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. (19)

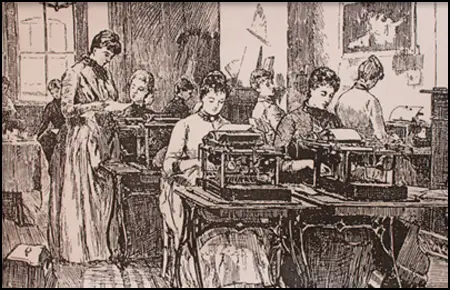

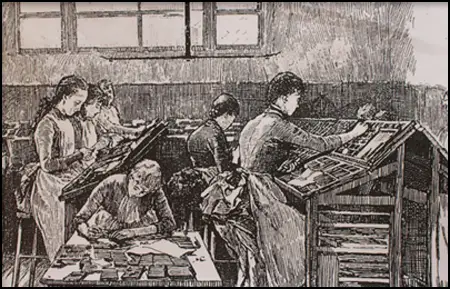

On 25th March 1860, Emily Faithfull established the Victoria Press at Great Coram Street, London. She invested her own capital in the press and had the financial backing of another committee member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. The Victoria Press printed The English Woman's Journal. The press employed at the outset women compositors, despite the trade restrictions practised by men, but the venture was to remain an irritant to many compositors and others in the printing trade. (20) Elizabeth Rayner Parkes wrote in her diary: "They will employ at least 6 girls; so here are women in the trade at last! One dream of my life!" (21)

Kensington Society

In May 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. It's founder members were the same women who formed the Langham Place Group and had been involved in the married women's property agitation and who had struggled to open local education examinations to girls. (22)

Membership was by personal invitation. The secretary, Emily Davies, brought together women "having more or less common interests and aims". Many were already friends, or were relatives of members. Others had been involved in the English Woman's Journal and had supported the campaign to open the Cambridge University local examinations to girls in 1864. Some met and shared ideas at the society for the first time. (23)

One of the founders of the group was Alice Westlake. On 18th March, 1865, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." (24) Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse." (25)

The Kensington Society had about fifty members, including Jessie Boucherett, Barbara Bodichon (artist), Emily Davies (educationalist), Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Frances Power Cobbe (journalist), Anne Clough (educationalist), Alice Westlake (artist), Helen Taylor (educationalist), Elizabeth Garrett (medical student), Sophia Jex-Blake (medical student), Bessie Rayner Parkes (writer) and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy (headmistress). (26)

Members of the Kensington Society were united by the opportunity to debate issues in a private, yet formal, setting. The women wanted practice in formal debating to build confidence for future public speaking. Some of the subjects discussed included: "What are the tests of originality?", "Is it desirable to employ emulation as a stimulus to education?" and "What form of government is most favourable to women?" In November 1865 the question was debated: "Is the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" (27)

Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. (28) Ann Dingsdale points out: "The annual subscription was half a crown. Questions for debate were issued four times a year and members might speak at meetings or submit written answers. Corresponding members submitted papers that were discussed by those who could attend (and who paid a further half-crown for that privilege). By conducting its debates in a private arena, with apparently unminuted discussions, the society encouraged a frank exchange of views." (29)

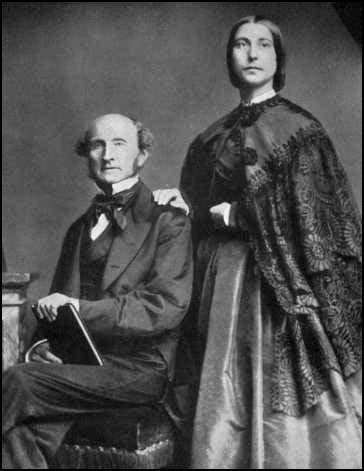

Helen Taylor was an important member of the Kensington Society because she was the step-daughter of John Stuart Mill, a philosopher who fully supported women's suffrage. In an article published in 1861 he argued: "In the preceding argument for universal, but graduated suffrage I have taken no account of difference of sex. I consider it to be as entirely irrelevant to political rights, as differences in height, or in the colour of the hair. All human beings have the same interest in good government; the welfare of all is alike affected by it, and they have equal need of a voice in it to secure their share of its benefits. If there be any difference women require it more than men, since being physically weaker, they are more dependent on law and society for protection." (30)

John Stuart Mill was invited by the Liberal Party to stand for the House of Commons in the 1865 General Election for Westminster. The Kensington Society saw this as an opportunity to promote the campaign for women's suffrage. In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Mill's step-daughter, Helen Taylor: "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time... Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately." (31)

Helen Taylor replied the same day: "It seems to me that while a Reform Bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from different classes - asking for representation or protesting against disenfranchisement should say so, and that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so, and that women not saying so now will be used against them in the future and delay the time of their enfranchisement.... I think the most important thing is to make a demand and commence the first humble beginnings of an agitation for which reasons can be given that are in harmony with the political ideas of English people in general. No idea is so universally accepted and acceptable in England as that taxation and representation ought to go together, and people in general will be much more willing to listen to the assertion that single women and widows of property have been overlooked and left out from the privileges to which their property entitles them, than to the much more startling general proposition that sex is not a proper ground for distinction in political rights." (32)

Helen Taylor stated that "If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up" her father would be willing to present it to Parliament." Two days later Barbara Bodichon replied that a small group including herself, Jessie Boucherett, Bessie Rayner Parkes and Elizabeth Garrett, had already started collecting signatures. (33) On receiving Taylor's draft petition, Bodichon commented it was too long and "it would be better to make it as short as possible and to state as few reasons as possible for what we want, everyone has something to say against the reasons." (34)

On 20th May 1867, Mill made a speech in the House of Commons where he proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together." (35)

In less than a month the Kensington Society collected nearly 1,500 signatures (one important member, Dorothea Beale, refused to sign the petition. Helen replied when it was delivered: "My father will present the petition tomorrow (if that is still the wish of the ladies) and it should be sent to the House of Commons to arrive there before two p.m. tomorrow, Thursday June 7th directed to Mr Mill, and petition written on it. It is indeed a wonderful success. It does honour to the energy of those who have worked for it and promises well for the prospects of any future plan for furthering the same objects." (36)

On 7th June, 1867 Barbara Bodichon was ill and so Elizabeth Garrett and Emily Davies, escorted the great scroll to Westminster Hall and gave their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Mill, said, "Ah! this I can brandish with effect." (37) Louisa Garrett Anderson later recalled: "John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again." (38)

hiding first women’s suffrage petition under an apple-woman’s stall in Westminster Hall

until John Stuart Mill came to collect it.

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment to the 1867 Reform Act was defeated by 196 votes to 73. William Gladstone, was one of those who voted against the amendment. (39)

Women's Suffrage

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. John Stuart Mill became president and other members included Jessie Boucherett, Helen Taylor, Frances Power Cobbe, Lydia Becker, Millicent Fawcett, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Elizabeth Garrett, Anne Clough, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Louisa Garrett Smith, Alice Westlake and Priscilla McLaren. (40)

By the 1890s there were seventeen individual groups that were advocating women's suffrage. This included the London Society for Women's Suffrage, Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage and the Central Committee for Women's Suffrage. On 14th October 1897, these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Lydia Becker was elected as president and Boucherett joined the executive committee of the NUWSS. (41)

Boucherett wrote several books including: Hints on Self-Help for Young Women (1863), The Conditions of Women in France (1868) an essay on How to provide for Superfluous Women in Women's Work and Women's Culture (1869), that was edited by Josephine Butler. She also wrote numerous tracts and pamphlets, and edited The Englishwoman's Review. In the 1880s she attempted "to persuade ladies of small means to turn their attention to pig and poultry farming; for in her opinion a clever, active women could add considerably to her income by so doing." (42)

Jessie Boucherett died from liver cancer on 18th October 1905 at Willingham House. Her estate was assessed at over £39,000. She left £2,000 to the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, £2,000 to the Freedom of Labour Defence Society, £500 to the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection and £500 to the English Woman's Journal.

Primary Sources

(1) Frances Hays, Women of the Day: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Contemporaries (1885)

Boucherett. Emilia Jessie, born in 1825, is the descendant of a French Protestant family who settled in North Willingham, Lincolnshire, some two hundred years ago. From early youth Miss Boucherett evinced great interest in the condition of her sex, and was mainly instrumental in founding the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women; she was also one of the earliest promoters of the Women's Suffrage Movement, and a strong supporter of the Married Woman's Property Act.

Miss Boucherett has written: Hints on Self-Help for Young Women (1863), The Conditions of Women in France (1868) an essay on How to provide for Superfluous Women in Mrs Josephine E. Butler's Women's Work and Women's Culture (1869), numerous tracts and pamphlets, and has also edited The Englishwoman's Review .

Her present endeavor is to persuade ladies of small means to turn their attention to pig and poultry farming; for in her opinion a clever, active women could add considerably to her income by so doing.