Ethel Wright

Caroline Elizabeth Wright (known by her friends, and professionally, as Ethel Wright), the daughter of John Wright, was born in London between 1866 and 1869. (1)

According to Elizabeth Crawford she began her art training by copying pictures in the National Gallery. (2) Wright became a part time art student in the studio of John Seymour Lucas, before going, on the advice of Solomon Joseph Solomon, to study at Académie Julian under Rodolphe Julian in Paris. (3)

In an interview Wright gave to The Tatler she admitted that she "began studying art at an early age and like many others started in a wrong direction by trying to paint before she could draw, but happily for her this error was pointed out when she was quite young." It was Soloman who told her to go to Paris "to have all the nonsense taken out of me." Wright added she "worked very hard during my studies in Paris and incidentally had a very good time of it. In the evening I often used to go to the Latin Quarter where most of the students and artists lived and met them at their studios or rooms, and the fun and laughter amongst us I can best describe perhaps as being immense. (4)

On her return to London, Solomon Joseph Solomon painted her portrait and exhibited it at Grosvenor Gallery in 1888. This was also the year that Ethel Wright began to exhibit her paintings at the Royal Academy. In 1890 she exhibited with the Society of British Pastellists alongside other women artists such as Louise Jopling Rowe and Emily Osborn. (5) In 1891 Arthur Hacker painted a large portrait of Ethel Wright. According to one source, Ethel sat for Hacker "over 50 times". (6)

In 1891 Ethel Wright is recorded as an "Artist Painter" residing at No. 8 Elm Tree Road, Marylebone, London and she told the census enumerator she was 22 years-old which suggests a birth year of 1868 or 1869. (7) Wright developed a successful career, particularly as a society portrait painter, and in 1893 was living in St John's Wood "in the most enchanting of artistic houses and a studio rich in clever portraits and rich imagination." (8)

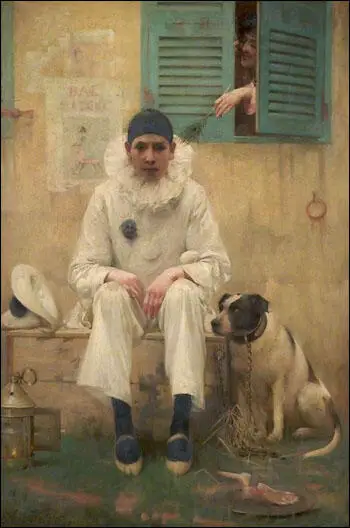

Bridget Clarke has pointed out that Ethel Wright's portrait was included in The Year’s Art in 1896, as part of a feature on "the more celebrated Lady Artists of the present time." In exhibition, Wright’s work was more often presented or critiqued in the context of "women’s work". (9) Her painting, Bonjour, Pierrot, was "displayed on the conveted line at the Royal Academy in 1892." (10)

Ethel Wright married Bernard Armiger Barczinsky (1858-1930), a theatrical proprietor, in Liverpool on 28th April 1897. Soon afterwards he changed his name to Armiger Barclay. During the early years of her marriage, Ethel Wright exhibited her work under her married name - Mrs Armiger Barclay. However, by 1900 Barclay had deserted his wife. (11)

It seems that Armiger Barclay was not completely honest with his bride-to-be about his financial situation. A few years later she wrote a letter to her husband saying it was a "rude awakening when I discovered that your position and means were not such as you had previously represented them to be. You have only to find a home and provide some support according to our position in life". (12) In his reply he claimed he had no money and could not help her financially: "I have had to borrow £10 to carry over Christmas" adding that he was "not able to oblige you, especially as you have an assured income of your own amply sufficient for your wants". (13)

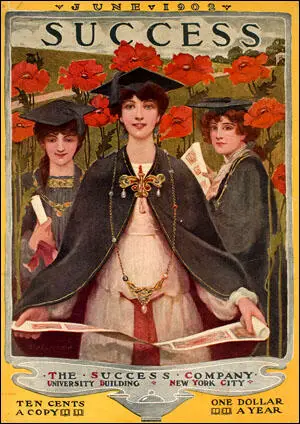

In 1901 Ethel Wright moved to the United States where she worked as an illustrator and portrait painter. Wright told the The American Register: "The art of the illustrator, she says, is much more advanced in America than in England, but the art of the painter on the other side of Atlantic leaves much to be desired. Perhaps, she thinks, it is the public who are to blame. The American artist must paint pretty pictures…. I painted very many portraits in America. American women are splendid subjects. There is a beauty, charm, and brightness about them that fascinates the portrait painter. The men are not so good." (14)

Ethel Wright returned to England in 1905. Her marriage difficulties resulted in her becoming a supporter of women's suffrage and became associating with members of the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). He reputation as a portrait painter resulted in the WSPU commissioning her to paint a portrait of Christabel Pankhurst. (15) Rosie Broadley has pointed out: "It is an amazing painting, a historical document as much as portrait. It was supposed to inspire people and present Pankhurst as a figurehead, leading a charge." (16)

The art historian, Alicia Foster, has argued: "In this painting, public heroism is signalled through Pankhurst's grand rhetorical gesture. However it is also allied to 'womanly' elegance and civilisation – skilfully countering the vicious caricatures of suffragettes in some sectors of the press – through the high polish of Wright's style and the sitter's graceful dress." (17) Another art critic as suggested that Wright's painting "embodies the awakened spirit of women." (18)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The painting was purchased for 100 guineas by her friend Una Dugdale one of the leaders of the women's suffrage movement who had given up almost the whole of her spare time to political propaganda." (19) The portrait of Christabel Pankhurst was exhibited at a large exhibition organised by the Women Social & Political Union and funded by Clare Mordan in 1909, and embodies the "awakened spirit" of women that was identified in the catalogue for that exhibition. (20) At the time Ethel Wright was active in the Chelsea branch of the WSPU. (21)

Ethel Wright also painted a portrait of Gabrielle Enthoven an active member of the Actresses' Franchise League (AFL). An organisation established by Edith Craig. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays. Enthoven was a founding member and president of the Pioneer Players, a feminist theatre company that aimed to present plays of "interest and ideas" that dealt with current social, political, and moral issues. (22)

Ethel Wright was in conflict with her husband Bernard Barclay, who was now working as a journalist. She at first she applied for restitution of conjugal rights. When he refused to return in August 1910 she filed for divorce on grounds of “adultery coupled with desertion”. At the time Barclay living with a young woman named Marguerite Jervis (born 1886, Burma) in Hertfordshire. A decree nisi was issued on 21st November 1910, and the divorce was finalised on 29th May 1911. (23)

On 13th January 1912 Una Dugdale married Victor Duval. Duval was a strong supporter of women's suffrage. (24) His sister, Elsie Duval, had been a member of the Women's Freedom League and the Women Social & Political Union. Victor Duval was also the founder of Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement. "The society was formed as a result of a growing conviction among men, as well as women, that the delay in removal of the sex disqualification from the Parliamentary franchise was due to the determined indifference of the Government rather than to any considerable opposition in the country." (25)

It was announced that the word "obey" would be omitted from the marriage service at the Savoy Chapel. However, the Archbishop of Canterbury, sent his representative to tell the Rev. Hugh Chapman, that the omission would make the validity of the marriage doubtful. "The couple acquiesced, and the usual marriage ceremony was proceeded with." (26)

As Catherine Blackford pointed out: "Marriage reform had long been a feminist concern and Duval's standpoint signified a feminist commitment to marriage as an equal partnership based on love and respect rather than subservience and subordination." (27) Later that year she explained her reasons for departing from convention in her pamphlet Love and Honour but not Obey. The illustration on the front page was based on a portrait of Una Dugdale that had been painted by Ethel Wright. (28)

In 1915 Ethel Wright painted a portrait of Lady Beatrice Lever, the former Beatrice Hilda Falk. She was the wife of Sir Arthur Levy Lever, the Liberal Party MP for Harwich. Lady Lever later became one of the 38,000 women who became Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD) during the First World War. VADs worked as assistant nurses, ambulance drivers and cooks. (29)

Ethel Wright lived and worked at 56 Glebe Place in Chelsea, home to many active suffrage artists. (30) Wright continued her association with the suffrage movement whilst continuing to exhibit annually at the Royal Academy until 1927. (31)

Ethel Wright of 4 Earls Terrace, Kensington, London, died on 6th July 1939. She left effects valued at £3,025 16s 5d. (32)

Primary Sources

(1) The American Register (13th August 1905)

Miss Ethel Wright, the well-known painter, has just returned to London, after four years' hard work in America, where she has had many delightful experiences.

The art of the illustrator, she says, is much more advanced in America than in England, but the art of the painter on the other side of Atlantic leaves much to be desired. Perhaps, she thinks, it is the public who are to blame. The American artist must paint pretty pictures….

I painted very many portraits in America. American women are splendid subjects. There is a beauty, charm, and brightness about them that fascinates the portrait painter. The men are not so good.

(2) The Tatler (23rd September 1908)

Miss Ethel Wright began studying art at an early age and like many others started in a wrong direction by trying to paint before she could draw, but happily for her this error was pointed out when she was quite young. "I happened," said Miss Wright, "to meet Mr S. T. Soloman, RA, and at his advice went to Paris to study, or to quote his words, "to have all the nonsense taken out of me." It was not very flattering advice but it was pre-eminently sensible, and I have worked very hard during my studies in Paris and incidentally had a very good time of it. In the evening I often used to go to the Latin Quarter where most of the students and artists lived and met them at their studios or rooms, and the fun and laughter amongst us I can best describe perhaps as being "immense".

(3) Mark Brown, The Guardian (24th July, 2014)

The National Portrait Gallery unveiled a portrait on Thursday, going on public display for the first time in 80 years, of a woman who became a figurehead for the militant wing of the suffrage movement.

Next door a display marks – not celebrates, said NPG associate curator Rosie Broadley – a significant moment in the gallery's history: the day, 100 years ago this month, that a suffragette attacked one of its paintings.

Broadley said for a long time the only portraits the gallery had of suffragettes were the surveillance photos supplied to it by the police.

The painting of Christabel Pankhurst shows a woman in full swagger, wearing her suffragette sash with pride and emerging from darkness looking as if she is about to speak with passion.

"It is an amazing painting, a historical document as much as portrait," said Broadley. "It was supposed to inspire people and present Pankhurst as a figurehead, leading a charge."

Pankhurst was the daughter of the suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst and a prominent strategist in the campaign. By 1912, fed up with the limited success of moderate tactics, she was urging a more militant approach....

The full-length portrait of Christabel Pankhurst was painted in 1909 by Ethel Wright, a society portraitist who supported the suffrage cause.

It was bought by the prominent suffragette Una Dugdale Duval, a woman who sparked incredulity in polite society by refusing to promise to "obey" at her wedding. The portrait passed down through the family and was bequeathed to a grateful NPG in 2011.

(4) Rosie Broadley, Suffragette Painter: Discovering Ethel Wright (5th March 2015)

The aim of International Women’s Day 2015 on Sunday 8th March is to encourage effective action for advancing and recognising women. This year’s theme is Make it Happen, which echoes the spirit of the militant suffragette’s motto of a hundred-years’ earlier, ‘Deeds not Words’; a call-to-action for disenfranchised British women. Two portraits of leading militant suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst by Georgina Brackenbury and her daughter Dame Christabel Pankhurst, painted by Ethel Wright, are currently on display in the twentieth-century galleries. The portrait of Dame Christabel was bequeathed in 2011 by the daughter of the prominent suffragette Una Dugdale Duval who had acquired the portrait soon after it was completed in 1908. It shows Christabel in the throes of oratory; wearing the purple, green and white sash of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the organisation founded by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903.

The Pankhursts and their achievements are well-known today, but what of the far less well-known painter Ethel Wright, who made this unique image? Contemporary art periodicals reveal that Wright enjoyed modest success as a fashionable ‘lady artist’ in the 1880s and 90s, regularly exhibiting at the Royal Academy , and known for her paintings of pierrots. Her portrait was included in ‘The Year’s Art’ in 1896, as part of a feature on ‘the more celebrated Lady Artists of the present time.’ In exhibition, Wright’s work was more often presented or critiqued in the context of ‘women’s work’. Frustration with the limitations imposed on women’s artistic output and ambition may have led Wright to the suffrage movement. Her portrait of Christabel was exhibited at a large exhibition organised by Pankhurst’s WSPU in 1909, and embodies the ‘awakened spirit’ of women that was identified in the catalogue for that exhibition. Wright continued her association with the suffrage movement whilst continuing to exhibit annually at the Royal Academy until 1927.

(5) Alicia Foster, Facing the New Century: Women Artists 1900–1909 (18th Jan 2021)

The fight for women's suffrage is the setting in which Ethel Wright's portrait of the feminist leader, campaigner and activist Christabel Pankhurst should be understood. In this painting, public heroism is signalled through Pankhurst's grand rhetorical gesture. However it is also allied to 'womanly' elegance and civilisation – skilfully countering the vicious caricatures of suffragettes in some sectors of the press – through the high polish of Wright's style and the sitter's graceful dress.

During her long career, Wright's practice evolved. In the late-nineteenth century, she exhibited as a society portraitist at The Royal Academy, and although she continued to exhibit at the RA, her portraits would become increasingly political. In her painting of Pankhurst, she combined the academic style that had won her some success at the Academy with radical subject matter. The painting was shown at the Women's Exhibition organised by the suffragette's Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1909.

(6) Bridget Clarke, Ethel Wright: St John's Wood Art School (2021)

Contemporary art periodicals reveal that Wright enjoyed modest success as a fashionable ‘lady artist’ in the 1880s and 90s, regularly exhibiting at the Royal Academy , and known for her paintings of pierrots. Her portrait was included in ‘The Year’s Art’ in 1896, as part of a feature on ‘the more celebrated Lady Artists of the present time.’ In exhibition, Wright’s work was more often presented or critiqued in the context of ‘women’s work’. Frustration with the limitations imposed on women’s artistic output and ambition may have led Wright to the suffrage movement.

Her portrait of Christabel Pankhurst, the noted suffragette, was exhibited at a large exhibition organised by Pankhurst’s WSPU in 1909, and embodies the "awakened spirit" of women that was identified in the catalogue for that exhibition. Wright continued her association with the suffrage movement whilst continuing to exhibit annually at the Royal Academy until 1927. The portrait of Dame Christabel was bequeathed in 2011 to the NPG by the daughter of the prominent suffragette Una Dugdale Duval who had acquired the portrait soon after it was completed in 1908. It shows Christabel in the throes of oratory; wearing the purple, green and white sash of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the organisation founded by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903.

(7) David Simkin, Family History Research (14th April, 2023)

Caroline Elizabeth Wright (known by her friends, and professionally, as "Ethel Wright"*) was born in London between 1866 and 1869. On her marriage certificate she declared that her father was John Wright, "Gentleman". According to the bride, her father was deceased by the time she married in April 1897. In her petition for the restitution of conjugal rights in 1910, Mrs Caroline Elizabeth Barczinsky explained that she used the Christian name 'Ethel' because it "is the name by which I have hitherto been commonly called and known."

There is a mystery about her year of birth. On the marriage certificate, dated 27th April 1897, she gave her age as "24 years" which would indicate a year of birth of 1872/1873. As she first exhibited her paintings in 1887, or even earlier, a birth date in the early 1870s seems unlikely. In the 1891 Census, Ethel Wright is recorded as an "Artist Painter" residing at No. 8 Elm Tree Road, Marylebone, London and she told the census enumerator she was 22 years-old which suggests a birth year of 1868 or 1869. If we accept that the artist Ethel Wright died in Kensington in 1939 at the age of 73, it would make her year of birth circa 1866 (the date taken as fact by historians and writers on Art).

Caroline Elizabeth Wright married Bernard Armiger Barczinsky at The Register Office, Liverpool on 2th April 1897.

Bernard Armiger Barczinsky anglicized his surname to 'Barclay' and was known as Armiger Barclay. During the early years of her marriage, 'Ethel' Wright exhibited her work under her married name i.e. Mrs A. Barclay.(Mrs Armiger Barclay).The 1891 Census records Ethel Wright as an "Artist Painter" No 8 Elm Tree Road, St Johns Wood, North West London.Her neighbours were two well-known artists, both genre & portrait painters.: Bernard Evans Ward (1857-1933) who rented a studio at Nos. 5,6,8 & 7 Elm Tree Road and Arthur Dampier May (1857-1916) who resided at No 8 Elm Tree Road,

Ethel Wright contributed paintings annually to the exhibitions at the Royal Academy between 1893 and 1900. 1893: "Milly", "Echo", 1894: "The Prodigal", 1895: "Lilies" (watercolour), 1896:"Rejected", 1897: Portrait of Mrs Laurence Phillips' 1898: "The Song of Ages", 1899: Portrait of Mrs Arthur Strauss, 1900: Portrait of Miss Vaughan.

In 1896, Ethel Wright showed her 'Portrait of Mrs Halkett' at the 41st Exhibition of the Society of Lady Artists.

Bernard Armiger Barczinsky was born in Sunderland, County Durham in 1858, the eldest son of Samuel Barczinsky (c. 1832-1995) a "School Master" who originated from Nieszawa in Poland. At the time of the 1891 Census, 33-year old Bernard Armiger Barczinsky was employed as a "School Master" at his father's school, Warlingham School in Surrey. When he married Caroline Elizabeth Wright at Liverpool Register Office on 27th April 1897, Bernard Armiger Barczinsky gave his occupation as "Theatrical Proprietor".