Emily Ford

Emily Ford, the daughter of Robert Lawson Ford (1809–1878) a solicitor and Hannah Pease Ford (1814–1886), was born in Leeds on 21st April, 1850. Emily siblings were; Mary (1839-1894), Catherine (1841-1859), Anna (1843-1854), John (1844-1934), Thomas (1846-1918), Elizabeth (1848-1919) and Isabella (1855-1924). (1)

In 1865 the family moved to Adel Grange, a large property on the outskirts of the city. Her grandfather, Thomas Pease, had been one of the major shareholders of the Stockton to Darlington Railway.(2)

Robert and Hannah Ford were both Society of Friends and this influenced they way they raised their eight children. For example, although members of the upper middle-class, the Ford children were taught to treat the servants with "esteem, equality and friendship". Robert and Hannah Ford also believed in gender equality. Like her brothers, Emily was taught science and history, as well as art and literature. The children were encouraged to develop inquiring minds and at home were expected to take part in discussions about current political issues. (3)

Emily Ford studied at the Slade School of Art between 1875-1881. She was close to her cousin, Edward Pease, who along with his friends, Edith Nesbit, Hubert Bland, Havelock Ellis and Frank Podmore, established the Fabian Society in 1884. Emily also joined the group. Nesbit wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it." (4)

Emily Ford and Socialism

A supporter of women's suffrage Emily Ford joined the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage in 1886. Three years later she signed the Women Householder's Declaration in favour of women's suffrage, and in 1897 was one of seventy-six painters listed as supporting the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. During this period she painted the portrait of Josephine Butler, that is now in the Leeds Art Gallery. (5) Ford was also the vice-president of the Leeds Suffrage Society and designed its membership card. (6)

Emily Ford's painting, Towards the New Dawn was described as a feminist painting and was given by Millicent Fawcett to Newnham College in 1890. The painting, an allegory imbued with renewed and potentially radical significance thanks to its new title and location, was hung in Newnham’s Common Room, where it would have been visible to staff and students. (7)

Emily and her sister Isabella Ford, influenced by their friend, Edward Carpenter, both became socialists and helped form a Leeds branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Other local members included Mary Gawthorpe and Ethel Annakin, who were also active in the struggle for women's suffrage. (8) As a member of the Women's Trade Union League Ford supported strikes of women weavers and the tailoresses in 1888 and 1889 with practical assistance and contributions towards the strike fund. (9)

On 29th March 1890, at All Souls' Church, Leeds, Emily Ford was baptised into the Anglican faith. At the time of the 1891 Census Emily was residing at Adel Grange, near Leeds, with her two unmarried sisters Elizabeth (age 42) and Isabella (age 35). All three sisters stated that they were "Living on own means". Also living at Adel Grange were five domestic servants, a visitor, Violet M. King, aged 26, and Evelina M. Rawson, aged 18, an "Artist's Model". (10)

Artists Suffrage League

The Artists' Suffrage League (ASL) was founded in January 1907 by professional women artists to help with the preparations for the first large-scale public demonstration by the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Its object was "to further the cause of Women's Enfranchisement by the work and professional help of artists... by bringing in an attractive manner before the public eye the long-continued demand for the vote." (11)

The first chairperson of the Artists' Suffrage League was Mary Lowndes, an important stained-glass and poster artist. She designed many of the banners used by the NUWSS including those for the demonstration of 21 June 1908, and for the Women's Pageant of Trades and Professions held the following year at the Albert Hall as part of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance Congress. (12)

Emily Ford was appointed as vice-chairman of the ASL. (13) According to Dora Meeson Coates her cottage and studio at 44 Glebe Place, provided a meeting place for "artists, suffragists, people who did things. She had been a great beauty and, though no longer young... was still full of charm, with a wondrous energy for life and work." (14)

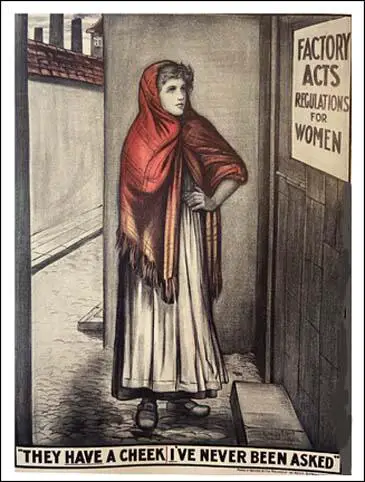

In 1908 Emily Ford produced one of the Artists' Suffrage League's most popular posters, "Factory Acts. They Have a Cheek. I've Never Been Asked." It was a protest against the various Factory Acts where the regulations governing women's work were made by men without consulting women workers. The art-work was also produced as a post-card that was sold at meetings. (15) It was also used by The Common Cause to illustrate an article on how the vote would affect the position of working women. (16)

Women's Coronation Procession

On 6th May 1911, Herbert Asquith, the prime minister, announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. (17) In an attempt to put pressure on the government, the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) decided to organise a Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17th June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. Christabel Pankhurst later wrote in Unshackled (1959): "Never had a year begun in so much hope. It might be coronation year for the women's cause as well as for the King and Queen." (18)

Other suffrage organisations including the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Women's Freedom League (WFL), Church League for Suffrage, Actresses' Franchise League, Artists' Suffrage League, Suffrage Atelier, Women's Tax Resistance League, Men's League For Women's Suffrage, Fabian Women's Group, Catholic Women's Suffrage Society and the Church Socialist League agreed to join the march. It was argued that "Everything depends on numbers, and if the deputation is sufficiently large, the authorities will be placed in an insurmountable difficulty." (19)

Emily Ford offered to make shield-shaped banners in the NUWSS colours, inscribed with the names of town councils that had passed resolutions in support of the Conciliation Bill, and "so made as to show no possible relation to the WSPU". Her offer was gratefully accepted by Philippa Strachey who promised the costs of eight shillings each: "The time seems dreadfully short and it will be truly noble if you can manage it." (20)

Election Fighting Fund

Emily Ford remained active in the Labour Party as well as the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. The Conciliation Bill was debated in March 1912, and was defeated by 14 votes. Asquith claimed that the reason why his government did not back the issue was because they were committed to a full franchise reform bill. However, he never kept his promise and a new bill never appeared before Parliament. (21)

Ray Strachey, the author of The Cause: A History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain (1928) pointed out that Millicent Garrett Fawcett now lost complete confidence in the Liberal Party to give women the vote: "Nothing more was ever hoped for the Liberal Party. The only prospect of successful lay in a change of Government, and to this end the women now devoted their energies." (22)

In early 1912 Millicent Garrett Fawcett and the NUWSS took the decision to form an electoral alliance with the growing Labour Party, as it was the only political party which really supported women's suffrage. "It soon strengthened that alliance, setting up a special Election Fighting Fund (EFF) in May-June so that the NUWSS could help Labour candidates more effectively at by-elections." (23)

As a socialist Emily Ford fully supported the EFF. A committee was formed to ensure the success of the EFF, this included her sister, Isabella Ford. Other members included Catherine Marshall, Margaret Ashton, Kathleen Courtney, Muriel de la Warr, Margory Lees and Ethel Annakin Snowden. In 1913–14 the EFF intervened in four by-elections and although Labour won none, the governing Liberal Party lost two seats. (24)

The First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (25)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote an article in The Suffragette where she argued: "A man-made civilisation, hideous and cruel enough in time of peace, is to be destroyed... This great war is nature's vengeance - is God's vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection... that which has made men for generations past sacrifice women and the race to their lusts, is now making them fly at each other's throats and bring ruin upon the world... Women may well stand aghast at the ruin by which the civilisation of the white races in the Eastern Hemisphere is confronted. This then, is the climax that the male system of diplomacy and government has reached." (26)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. (27) Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (28) In another interview she stated: "We suffragists... do not feel that Great Britain is in any sense decadent. On the contrary, we are tremendously conscious of strength and freshness." (29)

Emily Ford was a pacifist and so she was totally against Britain's involvement in the war. Despite pressure from some members of the NUWSS, Millicent Fawcett refused to argue against the First World War. At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace." Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." (30)

After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton in 1915 all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned over the decision not to support the Women's Peace Congress at the Hague. This included Chrystal Macmillan, Margaret Ashton, Kathleen Courtney, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden. "Wounding language was used on both sides. Mrs Fawcett did not normally turn disagreements among friends into quarrels but this one she experienced as a personal betrayal. It became the only episode in her life that she wished to forget". (31)

Religious Art

In 1916 Ford presented a number of works to the University of Leeds. Amongst these works were her monumental depictions of sibyls. The sibyls were seen as women of intense and considerable mental power, which shared a close proximity to the divine. Ford requested that these paintings be displayed 'where they could speak'. They now look over the university's ceremonial events and degree ceremonies as they hang above the platform in the Great Hall. (32)

After the war Emily Ford favoured religious decorative subjects. It has been pointed out: "The story of Emily Ford is one of shifting beliefs, colliding ideologies and unexpected connections.... Although her painting technique and style remained quite constant throughout her life, what she chose to paint changed along side her ever evolving beliefs.... Ford’s religious and ideological beliefs changed significantly throughout her life: socialist to Spiritualist to Anglican. One thing that remained steadfast, however, was her dedication to women’s rights activism. Swaying from her socialist doctrine to the budding Victorian Spiritualist movement, Ford took her commitment for social reform to new and unexpected places." (33)

Several London churches have mural paintings by her, as well as Newnham College. Janet Douglas, former lecturer in modern history at Leeds Beckett University says, “Emily painted many frescoes for Anglican churches and a number of her paintings now hang in the Great Hall of the University of Leeds. The font paintings are important because of the resurgence of interest in her work (she will feature in an exhibition in the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands next year) and also because they’re fascinating objects in themselves. The vivid colours had faded, the gilding was tarnished and details were barely visible, so it’s wonderful to see them brought back to life”. (34)

Emily Ford died at Adel Willows on 4th March 1930. John Rawlinson Ford, brother, and two nephews - Gervase Lawson Ford and Charles Lawson Smith - all three working as solicitors - served as executors of will. (35) In her will, from her estate of £24,291, she left a small legacy to Dora Meeson Coates. (36)

Primary Sources

(1) Alison Bogle, Little London Church Reveals Hidden Treasure (30th May, 2014)

On Saturday 7 June, All Souls’ church in Leeds is a holding an open day to celebrate the conservation of its unusual hidden treasure - eight paintings by Victorian artist and suffragist Emily Ford, who came from a renowned and politically radical family in Adel, and whose work is currently seeing a resurgence in interest.

The Revd Alice Snowden says, “Emily Ford was born into a Quaker family, but she was baptized into the CofE at All Souls' at the age of 39. In 1890 she paid for the ornate font cover as a thanksgiving for her baptism, and decorated the inside of it with her paintings. Although they are scenes from the Bible, she used the faces of her political colleagues (eg campaigners on education for women) and members of the congregation - eg, church warden E. J. Arnold, whose great grandson, Olav Arnold, will perform the formal unveiling.”

The family home in Adel was an alternative salon of radical figures, including the celebrated Russian anarchist Prince Kropotkin. Emily’s sister, Isabella Ford, was the famous trade union activist and suffragist, and together they founded the Leeds Suffrage Society in 1890. Emily was also the Vice-President of the Artists Suffrage League, which produced the memorable posters and banners for the suffrage marches.

Janet Douglas, lecturer in modern history at Leeds Metropolitan University (who will speak at the open day), says, “Emily painted many frescoes for Anglican churches and a number of her paintings now hang in the Great Hall of the University of Leeds. The font paintings are important because of the resurgence of interest in her work (she will feature in an exhibition in the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands next year) and also because they’re fascinating objects in themselves. The vivid colours had faded, the gilding was tarnished and details were barely visible, so it’s wonderful to see them brought back to life”.

All Souls (Backman Lane) will be open all day on 7 June with a varied programme of events (see below). Alice Snowden says, "Everyone’s welcome to drop in throughout the day. Researching some of the people in the paintings has brought up some fascinating history - we're very excited to share it!"

The £6000 needed for the paintings’ restoration was raised by the West Yorkshire Group of the Victorian Society.

(2) My Learning, Emily Ford (2023)

Emily was born in Leeds in 1850 and lived most of her life at Adel Grange with her sister Isabella. She was an artist and attended The Slade School of Fine Art in London.

Like her sister and father, Emily was very interested in education and was an active member of the Leeds Ladies Educational Association, who provided lectures and other training opportunities. They were also one of the organisations involved in the founding of Leeds Girls High School.

In 1866, aged 16, she joined the Manchester Suffrage Society and then went on to become Vice-President of the Leeds Suffrage Society which was formed in 1890.

She also become involved with the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), like her sister Isabella.

Although Emily was also born a Quaker, she later decided to convert to being an Anglican, and moved away from the socialist politics that Isabella was involved in. Her career as an artist continued alongside her suffrage campaigning, where she focused increasingly on religious art from around 1890. This included a series of panels that she painted for display at All Souls Church in Leeds, which were restored in 2014.

Alongside her religious art, including painting stained glass, she continued with her campaigning focused on the rights of women, and she became a member of a London suffrage society and was keen for her art to be used as part of the protest movement.

She later became a member and then Vice President of the Artists Suffrage League, and designed posters that were used in campaigns, alongside banners and other visual material, especially for the NUWSS.

In 1916, Emily donated a number of paintings to the University of Leeds where they were hung in the Great Hall. She died in 1930.

(3) Rights, Justice, Faith: The Work of Emily Susan Ford (13th December, 2018)

The story of Emily Ford is one of shifting beliefs, colliding ideologies and unexpected connections.

Ford was a painter of the Pre-Raphelite style working and living in Leeds from the mid 19th to the early 20th century. Although her painting technique and style remained quite constant throughout her life, what she chose to paint changed along side her ever evolving beliefs. How and why did Ford’s journey unfold?

Start in our exhibition in The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery and explore Ford’s fascinating biography. Here you can pick up a leaflet and follow the short route we have mapped out to The Great Hall to discover five of her impressive, large scale works.

Ford’s religious and ideological beliefs changed significantly throughout her life: socialist to Spiritualist to Anglican. One thing that remained steadfast, however, was her dedication to women’s rights activism. Swaying from her socialist doctrine to the budding Victorian Spiritualist movement, Ford took her commitment for social reform to new and unexpected places.

This exhibition, using collections from the University of Leeds, uncovers how these beliefs (which at first might seem completely apposed) share much more than you might expect.

(4) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987)

Emily S. Ford. Landscape nd figure painter. Society of Women Artists. Studied at the Slade from 1875. Sister of Isabella Ford, a prominent Leeds socialist, suffragist and Quaker, a member of the ILP and active supporter of the Women's Trade Union League. Emily Ford was vice-chairman of the ASL... Her portrait of Josephine Butler is in Leeds City Art Gallery.