On this day on 9th December

On this day in 1790 Richard Carlile, the son of a shoemaker from Ashburton, was born on 8th December, 1790. Richard's father abandoned the family in 1794 and it was a struggle for his mother to look after her three children from the profits of the small shop that she ran in the town. Richard received six years free education from the local Church of England school and learnt to read and write.

At the age of twelve Carlile left school and was apprenticed as a tinplateman in Plymouth. In 1813 he married a local woman and soon afterwards the couple moved to London. Over the next few years Jane Carlile gave birth to five children, three of whom survived.

Richard found work as a tinsmith but in the winter of 1816, Carlile had his hours reduced by his employer. Short-time work created serious economic problems for the Carlile family. For the first time in his life, Carlile began attending political meetings. At these meetings Carlile heard speakers like Henry Hunt complain bitterly about a parliamentary system that only allowed three men in every hundred to vote.

Carlile later wrote that as a young man he had the ambition to get my living by the pen, as more respectable and less laborious than working fourteen, sixteen and eighteen hours per day for a very humble living... I shared in the general distress of 1816, and it was this that opened my eyes. Having my attention drawn to politics, I began to read everything I could get at upon the subject with avidity, and I soon saw what was the importance of a free press."

Carlile found the arguments for reform convincing and began to wonder why it had taken him so long to realize that the system was unfair. As a young boy, Carlile remembered taking part in ceremonies where an effigy of Tom Paine was burnt at the stake. Carlile, like the rest of the people living in his village had believed the local vicar when he told them that Paine was an evil man for suggesting the need for parliamentary reform.

In 1817 he became a hawker of pamphlets and journals. The same year he met William Sherwin, who had just started Sherwin's Political Register, and they entered into a business arrangement whereby he became the journal's publisher. He also became the author of several pamphlets. Carlile tried to earn a living by selling the writings of parliamentary reformers on the streets of London. Later Carlile was to comment that he often walked "thirty miles for a profit of eighteen pence".

Carlile decided to rent a shop in Fleet Street and become a publisher. Instead of publishing works such as Paine's The Rights of Man and the Principles of Government in book form, Carlile divided them into sections and then sold them as small pamphlets. In August 1817, he reprinted the political parodies of William Hone and was imprisoned awaiting trial on charges of seditious libel and blasphemy. He remained there for four months until the charges were dropped on Hone's famous acquittal.

Carlile was convinced that the printing press had the power to change society. "The printing press has become the Universal Monarch and the Republic of Letters will go to abolish all minor monarchies, and give freedom to the whole human race by making it as one nation and one family." He thought this was so important that he was willing to go to prison for his beliefs.

During this period he developed the reputation as the most successful popularizer of Paine since the 1790s. This included the publication of Age of Reason, a book that was extremely critical of the Church of England and had been immediately banned when it initially appeared in 1797. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government and he was the subject of several prosecutions, throughout which he continued to publish despite intermittent spells in prison.

In March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined the organisation. Johnson was appointed secretary and Wroe became treasurer. The main objective of this new organisation was to obtain parliamentary reform and during the summer of 1819 it was decided to invite Richard Carlile, Major John Cartwright, and Henry Orator Hunt to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The men were told that this was to be "a meeting of the county of Lancashire, than of Manchester alone. I think by good management the largest assembly may be procured that was ever seen in this country." Cartwright was unable to attend but Hunt and Carlile agreed and the meeting was arranged to take place at St. Peter's Field on 16th August.

At about 11.00 a.m. on 16th August, 1819 William Hulton, the chairman, and nine other magistrates met at Mr. Buxton's house in Mount Street that overlooked St. Peter's Field. Although there was no trouble the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field by midday. Hulton therefore took the decision to send Edward Clayton, the Boroughreeve and the special constables to clear a path through the crowd. The 400 special constables were therefore ordered to form two continuous lines between the hustings where the speeches were to take place, and Mr. Buxton's house where the magistrates were staying.

The main speakers at the meeting arrived at 1.20 p.m. This included Richard Carlile, Henry 'Orator' Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson and Mary Fildes. Several of the newspaper reporters, including John Tyas of The Times, Edward Baines of the Leeds Mercury, John Smith of the Liverpool Mercury and John Saxton of the Manchester Observer, joined the speakers on the hustings.

At 1.30 p.m. the magistrates came to the conclusion that "the town was in great danger". William Hulton therefore decided to instruct Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, to arrest Richard Carlile and the other proposed speakers. Nadin replied that this could not be done without the help of the military. Hulton then wrote two letters and sent them to Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange, the commander of the military forces in Manchester and Major Thomas Trafford, the commander of the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry.

When Captain Hugh Birley and his men reached the hustings they arrested most of the men. As well as the speakers and the organisers of the meeting, Birley also arrested the newspaper reporters on the hustings. John Edward Taylor reported: "A comparatively undisciplined body, led on by officers who had never had any experience in military affairs, and probably all under the influence both of personal fear and considerable political feeling of hostility, could not be expected to act either with coolness or discrimination; and accordingly, men, women, and children, constables, and Reformers, were equally exposed to their attacks."

Samuel Bamford was another one in the crowd who witnessed the attack on the crowd: "The cavalry were in confusion; they evidently could not, with the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; and their sabres were plied to cut a way through naked held-up hands and defenceless heads... On the breaking of the crowd the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing whenever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Women and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled... A young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises. In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space. The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flag-staves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two dropping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. Several mounds of human flesh still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered. Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe again."

Lieutenant Colonel L'Estrange reported to William Hulton at 1.50 p.m. When he asked Hulton what was happening he replied: "Good God, Sir, don't you see they are attacking the Yeomanry? Disperse them." L'Estrange now ordered Lieutenant Jolliffe and the 15th Hussars to rescue the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry. By 2.00 p.m. the soldiers had cleared most of the crowd from St. Peter's Field. In the process, 18 people were killed and about 500, including 100 women, were wounded.

Richard Carlile managed to avoid being arrested and after being hidden by local radicals, he took the first mail coach to London. The following day placards for Sherwin's Political Register began appearing in London with the words: 'Horrid Massacres at Manchester'. A full report of the meeting appeared in the next edition of the newspaper. The authorities responded by raiding Carlile's shop in Fleet Street and confiscating his complete stock of newspapers and pamphlets.

Carlile now decided to change his newspaper's name to The Republican. In the first edition he wrote about the Peterloo Massacre: "The massacre of the unoffending inhabitants of Manchester, on the 16th of August, by the Yeomanry Cavalry and Police at the instigation of the Magistrates, should be the daily theme of the Press until the murderers are brought to justice. Captain Nadin and his banditti of police, are hourly engaged to plunder and ill-use the peaceable inhabitants; whilst every appeal from those repeated assaults to the Magistrates for redress, is treated by them with derision and insult. Every man in Manchester who avows his opinions on the necessity of reform, should never go unarmed - retaliation has become a duty, and revenge an act of justice."

Carlile not only described how the military had charged the crowd but also criticised the government for its role in the incident. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government. The authorities also disapproved of Carlile publishing books by Tom Paine, including Age of Reason, a book that was extremely critical of the Church of England. In October 1819, Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and was sentenced to six years in Dorchester Gaol.

Carlile was also fined £1,500 and when he refused to pay, his Fleet Street offices were raided and his stock was confiscated. Carlile was determined not to be silenced. While he was in prison he continued to write material for The Republican, which was now being published by his wife. Due to the publicity created by Carlile's trial, the circulation of the newspaper increased dramatically and was now outselling pro-government newspapers such as The Times.

The government was greatly concerned by the dangers of the parliamentary reform movement and Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, wrote a letter to Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, arguing that the government needed to take firm action. This was supported by John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, the Lord Chancellor, who was of the clear opinion that the Peterloo meeting "was an overt act of treason".

As Terry Eagleton has pointed out the "liberal state is neutral between capitalism and its critics until the critics look like they're winning." (16) When Parliament reassembled on 23rd November, 1819, Sidmouth announced details of what later became known as the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was the "curbing radical journals and meeting as well as the danger of armed insurrection".

This included: (v) The Basphemous and Seditious Libels Act: A measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious. (vi) Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act: A measure which subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty. The government imposed a 4d. tax on cheap newspapers and stipulating that they could not be sold for less than 7d. As most working people were earning less than 10 shillings a week, this severely reduced the number of people who could afford to buy radical newspapers.

A Stamp Tax had been first imposed on British newspapers in 1712. The tax was gradually increased until in 1815 it had reached 4d. a copy. As few people could afford to pay 6d. or 7d. for a newspaper, the tax restricted the circulation of most of these journals to people with fairly high incomes. During this period most working people were earning less than 10 shillings a week and this therefore severely reduced the number of people who could afford to buy radical newspapers.

Campaigners against the stamp tax such as William Cobbett and Leigh Hunt described it as a "tax on knowledge". As Richard Carlile pointed out: "Let us then endeavor to progress in knowledge, since knowledge is demonstrably proved to be power. It is the power knowledge that checks the crimes of cabinets and courts; it is the power of knowledge that must put a stop to bloody wars."

Carlile spent most of his six years in prison in isolation. With the help of his family and friends Carlile was able to continue publishing The Republican. In 1820, to avoid Stamp Duty, Carlile put up the price of the newspaper to sixpence. Despite this move, people were still prosecuted for being involved in the publication of the newspaper. This included in the imprisonment of his wife, Jane Carlile (February 1821) and his sister, Mary-Anne Carlile (June 1822) for two years each. Jane was actually imprisoned with her husband and she gave birth to a daughter, Hypatia in June 1822.

These newspapers had no problems finding people willing to sell these newspapers. Joseph Swann had sold Carlile's pamphlets and newspapers in Macclesfield since 1819. He was arrested and in court he was asked if he had anything to say in his defence: "Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament... I wish every man to read those publications." The judge responded by sentencing him to three months hard labour.

It has been argued that the significance of Carlile's achievement lies in his contribution to the cause of free speech and a free press. "His publishing career and his championship of the oppressed, of no advantage to himself or his family, stand as testimony to the depth of commitment to be found in the artisan class of the early nineteenth century. Carlile never gave up, never became disaffected, and continuously sought to discover new opportunities of disseminating his conviction that freedom from the shackles of orthodoxy and oppression was essential for the future of his civilization".

Susannah Wright was a Nottingham lace-mender, who sold Carlile's newspapers and pamphlets. She appeared in court in November 1822 with her six-month old baby. The New Times reported that "this wretched and shameless woman" was an "abandoned creature who has cast off all the distinctive shame and fear and decency of her sex" and was a "horrid example" of a woman who gave support to the publication of "gross, vulgar, horrid blasphemy."

In court Susannah Wright argued that "a representative system of government would soon see the propriety of turning our churches and chapels into temples of science... cherishing the philosopher instead of the priest... As the blood of the Christian Martyrs become the seed of the Christian Church, so shall our sufferings become the seed of free discussion, and in those very sufferings we will triumph over you." After her long speech she "was applauded and loudly cheered" before being sent to Newgate Prison. It has been calculated that around 150 vendors and shopmen served over 200 years of imprisonment in the struggle for a free press.

Richard Carlile believed strongly in the educative possibilities of prison. In his letters to other imprisoned radicals he urged them to use the opportunity presented by their prison sentences to further their education. "We should have more philosophers in our gaols than debtors, smugglers or poachers". George Holyoake later argued that Carlile did not trust any man unless he had been imprisoned for his beliefs.

When Richard Carlile was released from prison in November 1825 he returned to publishing newspapers. In The Republican he argued: "My long confinement was, in fact, a sort of penal representation for the whole. I confess that I have touched extremes that many thought imprudent, and which I would only see to be useful with a view of habiting the Government and people to all extremes of discussion so as to remove all ideas of impropriety from the media which were most useful. If I find that I have done this I shall become a most happy man; if not, I have the same disposition unimpaired with which I began my present career-a disposition to suffer fines, imprisonment or banishment, rather than that any man shall hold the power and exercise the audacity to say, and to act upon it, that any kind of discussion is improper and publicly injurious."

The people who worked in Carlile's shop were also persecuted. The authorities used agents to buy newspapers and pamphlets and then gave evidence against them in court. He therefore devised a system that became known as the "invisible shopman". Instead of a counter, the shop used a partition in the middle of which an indicator could be pointed to the names of works arranged around a dial. Customers turned the finger to the book they needed, put their money in a slot, and the book dropped to them along a chute."

Carlile was now a strong supporter of women's rights. He argued that "equality between the sexes" should be the objective of all reformers. Carlile wrote articles in his newspapers suggesting that women should have the right to vote and be elected to Parliament. Carlile pointed out: "I do not like the doctrine of women keeping at home, and minding the house and the family. It is as much the proper business of the man as the woman; and the woman, who is so confined, is not the proper companion of the public useful man".

In 1826 Carlile published Every Woman's Book, a book "which argued for a rational approach to birth control, attacking the Christian demonization of sexual desire while denying the traditional chauvinist assumptions about women". It was "an important contribution to the nineteenth-century debate on birth control" but the book "damaged his support among radicals and the disaffected working class".

The Republican, which ceased publication in December 1826 as a consequence of a dwindling circulation. In his writings Carlile abandoned his stance as a rationalist and began to call himself a "Christian atheist". In early 1827 Carlile embarked on the first of a series of lecture tours in the southern provinces, and in July he set off for six months in the north. Christina Parolin has argued: "Though prison had developed him as a scholar... Carlile was a poor public speaker and lacked the charisma, showmanship and oratorical skills to sustain audiences."

Carlile was involved in the campaign against child labour in factories. In 1827 Carlile was given a copy of manuscript written by John Brown, a radical journalist from Bolton. Brown's manuscript was based on an interview with a former parish apprentice called Robert Blincoe. Carlile published Robert Blincoe's Memoir in his new newspaper, The Lion. Robert Blincoe's story appeared in five weekly episodes from 25th January to 22nd February, 1828.

In his introduction Carlile argued: "John Brown is now dead; he fell, about two or three years ago, by his own hand. He united, with a strong feeling for the injuries and sufferings of others. Hence his suicide. Had he not possessed a fine fellow-feeling with the child of misfortune, he would never have taken such pains to compile the Memoir of Robert Blincoe, and to collect all the wrongs on paper, on which he could gain information, about the various sufferers under the cotton-mill systems. The employment of children is bad for children - first, as their health - and second, as to their manners. The time should be devoted to a better education. The employment of infant children on the cotton-mills furnishes a bad means to dissolute parents, to live in idleness and all sorts of vice."

In May 1830 Carlile opened the Blackfriars Rotunda. Several times a week Carlile and invited speakers would "deliver attacks on the superstitions of Christianity, which Carlile had now identified as the single most obdurate opposition to reform and liberation". The Rotunda became an important centre for working-class dissent and political reform. Speakers included William Cobbett, Henry 'Orator' Hunt, Robert Owen, Daniel O'Connell, Robert Taylor and John Gale Jones. It is reported that at one meeting calling for parliamentary reform, drew a crowd of over 2,000 people.

Richard Carlile was pleased with what he had achieved at the Rotunda: "We have created the best school that was ever open to the human race. Oxford, Cambridge, the London University, the King's College are Folly's seats, contrasted to the Rotunda. There has been more expansion of mind generated at the Rotunda, in the last year, than in all the world beside."

Richard Carlile joined forces with William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, James Watson, John Cleave and William Benbow to form the National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC). It proposed universal male suffrage, annual parliaments, votes by secret ballot and the removal of property qualifications for MPs. Iain McCalman has claimed that it became the "most effective working-class radical organisation in the early 1830s."

Carlile published an article in his new newspaper, The Prompter, in support of agricultural labourers campaigning against wage cuts. Carlile's advice to the labourers was "to go on as you have done".This was interpreted by the authorities as a seditious call to arms. Carlile was arrested and charged with seditious libel and appeared at the Old Bailey in January 1831. Carlile argued that "neither in deed, nor in word, nor in idea, did I ever encourage acts of arson or machine breaking".

The court was not convinced by his arguments and Carlile was found guilty of seditious libel and received a sentence of two years' imprisonment and a large fine which he refused to pay, thereby extending the sentence by a further six months. While in prison he continued to write articles for radical newspapers and pamphlets such as New View of Insanity (1831).

While he was in prison he received a letter from Elizabeth Sharples, a 28 year-old woman from Bolton. After "a rapid exchange of correspondence in which admiration turned to ardent love, she determined to share his work". Even before he had met Sharples in person, Carlile anticipated that she would become "my daughter, my sister, my friend, my companion, my wife, my sweetheart, my everything".

In January 1832 Elizabeth Sharples moved to London and visited Carlile in prison. Carlile had always campaigned for women's rights and he invited her to speak at his Blackfriars Rotunda. Billed as "the first Englishwoman to speak publicly on matters of politics and religion" she gave her first talk on 29th January 1832. The Times reported that she was "pretty, with a good figure and genteel manners" and dressed very well.

Sharples pointed out in her speech: "I will set before my sex the example of asserting an equality for them with their present lords and masters, and strive to teach all, yes, all, that the undue submission, which constitutes slavery, is honourable to none; while the mutual submission, which leads to mutual good, is to all alike dignified and honourable... Cast in the role of the Egyptian goddess Isis, she stood on the stage of the theatre, the floor strewn with whitethorn and laurel, and delivered lectures on mystical religion and women's rights."

Elizabeth Sharples was appointed as editor of a new radical weekly publication, Isis. She gave two lectures every Sunday (at sixpence for the pit and boxes, one shilling for the gallery), on Monday evenings (for half-price). She also gave a free lecture on Friday evenings to accommodate those unable to afford the entry charges.

Not everybody enjoyed her speeches. One man wrote to a national newspaper attacking the idea of a woman speaking in public: "Elizabeth Sharples is a female who exhibits herself in so unfeminine a manner... So utterly illiterate is the poor creature, that she cannot yet read what is set down for her with any degree of intelligibility... with her ignorance and unconquerable brogue... her lecturing is almost as ludicrous as it is painful to witness."

Richard Carlile supported Sharples in her campaign for women's rights: "I do not like the doctrine of women keeping at home, and minding the house and the family. It is as much the proper business of the man as the woman; and the woman, who is so confined, is not the proper companion of the public useful man." (50) It has been claimed that "this just about sums up the position of women in the radical movement". Even if a woman was emancipated she was expected to be the "proper companion of the public useful man".

Elizabeth Sharples argued in her newspaper articles that Christianity was the chief barrier to the dissemination of knowledge; by denying the people education, priests were denying man's liberty. She suggested that passive and non-resistance was seen as the "doctrine of priesthood".

Sharples was Carlile's greatest supporter while he was in prison. She used the Rotunda platform" to castigate the priesthood, expose religious superstition and denigrate established authority". She promised "sweet revenge" on those responsible for the "incarceration of Carlile". She visited him in prison and began a sexual relationship.

In 1832 Jane Carlile moved out of the family home and started a bookshop of her own. In April 1833 Elizabeth Sharples gave birth to a son, Richard Sharples. Carlile realized that he would have to acknowledge their relationship, and thereupon declared that he and Eliza were joined in a "moral marriage".

Elizabeth Sharples had the task of running the Blackfriars Rotunda while Carlile was in prison. In February 1832, she reported that £1,000 was needed to keep the venture open, to cover rent, taxes, lights and repairs. At the same time there had been a reduction in audiences. She admitted that she had lost the support of the radical community: "I believe I stand alone in the country, as a modern Eve, daring to pluck the fruit of the tree, and to give it to timid, sheepish man. I have received kindnesses and encouragements from a few ladies since my appearance in the metropolis, but how few."

On his release from prison in August the couple lived on the corner of Bouverie Street and Fleet Street. Richard Sharples died of smallpox in October 1833. Another son, Julian Hibbert, was born in September 1834. In November 1835 they took a seven-year lease on a cottage in Enfield Highway, where shortly afterwards a daughter, Hypatia, was born. A fourth child, Theophila, followed a year later.

In August 1836 he set off again on tour, lecturing first at Brighton and then to the north, returning home in December. His biographer, Philip W. Martin, pointed out: "Carlile's position was shifting radically. While it is clear that he never retreated to orthodoxy, his increasing use of Christian rhetoric and his own claims for himself as a Christian were a far cry from the radicalism of his early years. Carlile still propounded a sceptical, rational view of religion, but his allegorical readings had diminished to a single interpretation of Christianity in which he saw Christ and the resurrection as the rebirth of the soul of reason in humankind".

Richard Carlile was still capable of drawing large crowds (1500 people in Leeds in 1839, and 3000 people in Stroud, in 1842), it was clear that most radicals rejected his religious views and were attracted to the political arguments of Chartism. He was also in poor health and he died of a bronchial infection on 10th February 1843. As he had dedicated his body to science it was taken to St Thomas's Hospital before his burial at Kensal Green Cemetery in London on 26th February.

On this day in 1842 the philosopher Peter Kropotkin, the son of Aleksei Petrovich Kropotkin and Yekaterina Nikolaevna Sulima, was born in Moscow, Russia, on 12th December, 1842. The family was fairly wealthy and came from a noble lineage (Peter was in fact a prince).

Peter's mother died of tuberculosis in 1846. Two years later his father married Yelizaveta Mar'kovna Korandino. According to one source: "Yelizaveta caused a great deal of tension in the house. An aggressive, domineering woman, she attempted to erase all traces of the children's departed mother rather than offering them comfort. These actions caused further resentment between the children and their father."

His brother Nikolai (born in 1834) left the family home for military service in the Crimean War. His other brother, Alexander Kropotkin (born in 1841) also left home to join the Moscow Cadet Corps. Peter and Alexander had spent a great deal of their early lives together and were very close. Peter went to study at the First Moscow Gymnasium. He was not terribly impressed with the school, feeling that "all the subjects were taught in the most senseless manner." However, while at school, he did develop a strong interest in history and geography. At the age of 15 Kropotkin entered the aristocratic Corps des Pages of St. Petersburg and four years later became personal page to Tsar Alexander II.

Peter Kropotkin n first became aware of political censorship in Russia when his older brother, Alexander, was arrested in 1858 while a student at St. Petersburg University as a result of having a copy of a book, Self-Reliance, by Ralph Waldo Emerson. The book had been lent to him by one of the faculty, Professor Tikhonravof, but he refused to tell the police this because he did not want to get into trouble with the authorities. When Tikhonravof heard of Kropotkin's arrest he went at once to the rector of the university, and admitted that he was the owner of the book, and the young student was released.

In 1862 he applied for a commission in the Cossack Regiment serving in Eastern Siberia. After reading the work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the exploits of Mikhail Bakunin he developed an interest in anarchism. Kropotkin took a growing interest in politics. As Paul Avrich points out: "In Siberia he shed his hopes that the state could act as a vehicle of social progress. Soon after his arrival, he drafted, at the request of his superiors, elaborate plans for municipal self-government and for the reform of the penal system (a subject that was to interest him for the rest of his life), only to see them vanish in an impenetrable bureaucratic maze."

Disillusioned by the limits of these reforms, he undertook a geographical exploration in East Siberia and produced a paper on his theory of mountain structure. Kropotkin's reports on the topography of Siberia won him immediate recognition and in 1871 he was offered the coveted post of secretary of the Imperial Geographical Society in St. Petersburg. However, he rejected the post because of his new political commitment. "Although I did not then formulate my observations in terms borrowed from party struggles, I may say now that I lost in Siberia whatever faith in state discipline I had cherished before. I was prepared to become an anarchist."

In 1872 Kropotkin joined a group that was spreading revolutionary propaganda among the workers and peasants of Moscow and St. Petersburg. He joined the Chaikovskii Circle, a group committed to disseminating propaganda among workers and peasants in order to prepare the way for a social revolution. They also published the work of writers such as Karl Marx, Alexander Herzen, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Peter Lavrov, John Stuart Mill and Charles Darwin.

In March 1874 he was arrested by the police. His house was searched and they found copies of a revolutionary manifesto that had been written by Kropotkin. They also found his diary and several books that had been banned by the authorities. Although they found plenty of incriminating evidence, the police had to bribe several witnesses to get a conviction. Kropotkin was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress but in 1876 he was able to escape and fled to Switzerland.

In 1876 his brother, Alexander Kropotkin, was arrested and charged with "political untrustworthiness" He was exiled to Minusinsk in Siberia, more than 3,000 miles from St. Petersburg and about 150 miles from the boundary line of Mongolia. His wife and children accompanied him into exile. He later told George Kennan that he thought he was being punished because of the political activities of his brother, Peter Kropotkin, who had been imprisoned two years earlier for being a member of the Chaikovskii Circle: "I am not a nihilist nor a revolutionist and I never have been. I was exiled simply because I dared to think, and to say - what I thought, about the things that happened around me, and because I was the brother of a man whom the Russian Government hated."

After the assassination of Tsar Alexander II his radical socialist views made him unwelcome in the country and in 1881 he moved to France where he became a member of the International Working Men's Association (the First International), a federation of radical political parties that hoped to overthrow capitalism and create a socialist commonwealth.

Kropotkin continued to be interested in the work of Charles Darwin. He had profound respect for Darwin's discoveries and regarded the theory of natural selection as "perhaps the most brilliant scientific generalization of the century". Kropotkin accepted that the "struggle for existence" played an important role in the evolution of species. He argued that "life is struggle; and in that struggle the fittest survive". However, Kropotkin rejected the ideas of Thomas Huxley who placed great emphasis on competition and conflict in the evolutionary process.

In 1880 Peter Kropotkin read an article by Karl Kessler, a Russian zoologist, entitled On the Law of Mutual Aid. Kessler's argued that cooperation rather than conflict was the chief factor in the process of evolution. He pointed out "the more individuals keep together, the more they mutually support each other, and the more are the chances of the species for surviving, as well as for making further progress in its intellectual development." Kessler died the following year and Kropotkin decided to spend time developing his theories.

Kropotkin published An Appeal to the Young in 1880. Anna Strunsky wrote that "hundreds of thousands had read that pamphlet and had responded to it as to nothing else in the literature of revolutionary socialism". Elizabeth Gurley Flynn later claimed that the message "struck home to me personally, as if he were speaking to us there in our shabby poverty-stricken Bronx flat."

In 1883 Kropotkin was arrested by the French authorities. He tried at Lyon, and sentenced, under a special law passed on the fall of the Paris Commune, to five years' imprisonment, on the ground that he had belonged to the International Working Men's Association. While in prison Kropotkin's first ideas on anarchism were published. He was eventually released in 1886 and moved to England. Over the next few years he lived in Harrow, Acton, Ealing, Bromley and Highgate.

While living in England he became friends with other socialists, including William Morris, Keir Hardie, James Mavor, Tom Mann and George Bernard Shaw. Hardie once commented that if we were all like Kropotkin "anarchism would be the only possible system, since government and restraint would be unnecessary". In 1886 Kropotkin and his socialist friends organized a mass rally in London protesting against the death sentences imposed on the conviction of Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, George Engel, Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab for the Haymarket Bombing.

In 1886 he helped to establish the anarchist journal, Freedom. As anarchism's most important philosophers he was in great demand as a writer and contributed to the journals edited by Benjamin Tucker (Liberty), Albert Parsons (Alarm) and Johann Most (Freiheit). Tucker praised Kropotkin's publication as "the most scholarly anarchist journal in existence."

The following year he published In Russian and French Prisons. He argued that prisons are "schools of crime" and that by "subjecting him to brutalizing punishments, teaching him to lie and cheat, and generally hardening him in his criminal ways, so that when he emerges from behind bars he is condemned to repeat his transgressions.... Prisons neither improve the prisoners nor prevent crime; they achieve none of the ends for which they are designed."

Kropotkin continued to develop his ideas on evolution. In 1888 Thomas Huxley published an article entitled The Struggle for Existence. He completely rejected Huxley's argument that competition among individuals of the same species is not merely a law of nature but the driving force of progress. Kropotkin replied to Huxley in a series of articles where he documented his theory of mutual aid with illustrations from animal and human life. Paul Avrich has argued: "Among animals he shows how mutual cooperation is practiced in hunting, in migration, and in the propagation of species. He draws examples from the elaborate social behavior of ants and bees, from wild horses that form a ring when attacked by wolves, from the wolves themselves that form a pack for hunting, from migrating deer that, scattered over a wide territory, come together in herds to cross a river. From these and many similar illustrations Kropotkin demonstrates that sociability is a prevalent feature at every level of the animal world. Moreover, he finds that among humans too mutual aid has been the rule rather than the exception. With a wealth of data he traces the evolution of voluntary cooperation from the primitive tribe, peasant village, and medieval commune to a variety of modern associations that have continued to practice Mutual support despite the rise of the coercive bureaucratic state. His thesis, in short, is a refutation of the doctrine that competition and brute force are the sole - or even the principal - determinants of social progress."

Alexander Kropotkin committed suicide on 25th July, 1890. The St Petersburg Eastern Review reported: "On the 25th of July, about nine o'clock in the evening, Prince A. A. Kropotkin committed suicide in Tomsk by shooting himself with a revolver. He had been in administrative exile about ten years, and his term of banishment would have expired on the 9th of next September. He had begun to make arrangements for returning to Russia, and had already sent his wife and his three children back to his relatives in the province of Kharkof. He was devotedly attached to them, and soon after their departure he grew lonely and low-spirited, and showed that he felt very deeply his separation from them. To this reason for despondency must also be added anxiety with regard to the means of subsistence. Although, at one time, a rather wealthy landed proprietor, Prince Kropotkin, during his long period of exile in Siberia, had expended almost his whole fortune; so that on the day of his death his entire property did not amount to three hundred rubles. At the age of forty-five, therefore, he was compelled, for the first time, seriously to consider the question how lie should live and support his family - a question which was the more difficult to answer for the reason that a scientific man, in Russia, cannot count upon earning a great deal in the field of literature, and Prince Kropotkin was not fitted for anything else. While under the disheartening influence of these considerations he received, moreover, several telegrams from his relatives which he misinterpreted. Whether he committed suicide as a result of sane deliberation, or whether a combination of circumstances super induced acute mental disorder, none who were near him at the moment of his death can say."

In 1892 Kropotkin published Conquest of Bread. It is generally agreed that the book is Kropotkin's clearest statement of his anarchist social doctrines. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "Written for the ordinary worker, it possesses a lucidity of style not often found in books on social themes." Emile Zola said that it was so well-written that it was a "true poem".

Kropotkin argued that the wage system, which presumes to measure the work of each individual in capitalism, must be abolished in favour of a system of equal rewards for all. Kropotkin suggested a system of "anarchist communism" by which private property and inequality of income would give place to the free distribution of goods and services. The author of Anarchist Portraits (1995) argued: "It was impossible to assess each person's contribution to the production of social wealth because millions of human beings had toiled to create the present riches of the world. Every acre of soil had been watered with the sweat of generations, every mile of railroad had received its share of human blood. Indeed, there was not a thought or an invention that was not the common inheritance of all mankind... Starting from this premise, Kropotkin argues that the wage system, which presumes to measure the work of each individual, must be abolished in favor of a system of equal rewards for all. This was a major step in the evolution of anarchist economic thought."

In Conquest of Bread Kropotkin argued that in an anarchist society no one would be compelled to work. He insisted that work is "a psychological necessity, a necessity of spending accumulated body energy, a necessity which is health and life itself. If so many) branches of useful work are reluctantly done now, it is merely because they mean overwork or they are improperly organized."

Peter Kropotkin was also highly critical of the education system which he described as a "university of laziness". He argued that it was: "Superficiality, parrot-like repetition, slavishness and inertia of mind are the results of our method of education. We do not teach our children to learn." Kropotkin was one of the first to argue for "an active outdoor education and learn by doing and observing at first hand".

Kropotkin insisted that the education system would have to be completely reformed in order to create an anarchist society. "We are so perverted by an education which from infancy seeks to kill in us the spirit of revolt, and to develop that of submission to authority; we are so perverted by this existence under the ferrule of a law, which regulates every event in life - our birth, our education, our development, our love, our friendship - that, if this state of things continues, we shall lose all initiative, all habit of thinking for ourselves. Our society seems no longer able to understand that it is possible to exist otherwise than under the reign of law, elaborated by a representative government and administered by a handful of rulers.... The education we all receive from the State, at school and after, has so warped our minds that the very notion of freedom ends up by being lost, and disguised in servitude."

Kropotkin rejected the idea of a secret revolutionary party that had been suggested by Mikhail Bakunin. He also criticized the views of Sergi Nechayev. He insisted that social emancipation must be attained by libertarian rather than dictatorial means. Kropotkin rejected the idea of revolution put forward by Bakunin and Nechayev in Catechism of a Revolutionist (1869): "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it." For Kropotkin the ends and the means were inseparable.

In 1897 his old friend, James Mavor, professor of political economy at the University of Toronto, invited him to speak at a conference in Canada. He was impressed by the agricultural abundance throughout the country and wrote to a friend: "How rich mankind could be if social obstacles did not stand everywhere in the way of utilising the gifts of nature."

In October 1897, Kropotkin crossed the border into the United States to meet fellow anarchist, Johann Most. Although they had disagreed in the past about politics, Kropotkin argued that "with a few more Mosts, our movement would be much stronger". Writing in the Freiheit Most described Kropotkin as the "celebrated philosopher of modern anarchism" and that it had been a pleasure "to look into his eyes and shake his hand".

At Jersey City he was asked by a group of journalists for a statement on his political beliefs: "I am an anarchist and am trying to work out the ideal society, which I believe will be communistic in economics, but will leave full and free scope for the development of the individual. As to its organization, I believe in the formation of federated groups for production and consumption.... The social democrats are endeavoring to attain the same end, but the difference is that they start from the centre - the State and work toward the circumference, while we endeavor to work out the ideal society from the simple elements to the complex."

The New York Herald reported: "Prince Kropotkin is anything but the typical anarchist. In appearance he is patriarchal, and while his dress is careless it is the carelessness of the man who is engrossed in science rather than that of the man who is in revolt against the usages of society. His manners are those of the polished gentleman, and he has none of the bitterness and dogmatism of the anarchist whom we are accustomed to see here."

In New York City Kropotkin spoke at a meeting chaired by John Swinton on the dangers of state socialism. One member of the audience later recorded that he "wore a patriarchal beard and beamed on his audience from behind a pair of spectacles like an old fashioned clergyman looking over a familiar congregation." Another remarked that "his evident sincerity and his kindness held the attention of his audience and gained its sympathy".

In 1899 Kropotkin visited Chicago and lived in the Hull House settlement, formed by Jane Addams, for a while. Alice Hamilton, one of the workers at the settlement, later recalled: "Prince Peter Kropotkin was one of the most lovable persons I have ever met. He was a typical revolutionist of the early Russian type, an aristocrat who threw himself into the movement for emancipation of the masses out of a passionate love for his fellow man, and a longing for justice. He stayed some time with us at Hull House, and we all came to love him, not only we who lived under the same roof but the crowds of Russian refugees who came to see him. No matter how down-and-out, how squalid even, a caller would be., Prince Kropotkin would give him a joyful welcome and kiss him on both cheeks."

Robert Lovett admitted that: "Hull House was emphatically the refuge of lost causes. The anarchist agitation had died out, but the fear of it was maintained by press and police to haunt the slumbers of the best people. Miss Addams was attacked for entertaining Peter Kropotkin in Hull House. The celebration of his birthday was an occasion for the visit to Chicago to the mild ghost of anarchism." Given this hostility Kropotkin decided to return to London.

In his final years Kropotkin concentrated on writing. His works during this period he produced an autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionist (1899), Fields, Factories and Workshops (1901), Mutual Aid (1902) and The Great French Revolution (1909) turned him into a world known political figure. Emma Goldman argued: "We saw in him the father of modern anarchism, its revolutionary spokesman and brilliant exponent of its relation to science, philosophy and progressive thought." and was described by Emma Goldman as the "godfather of anarchism".

In 1912 Kropotkin moved to Brighton where he stayed for the next five years. After the overthrow of the Tsar Nicholas II in 1917, Kropotkin returned home to Russia expecting the development of "anarchist communism". When the Bolsheviks seized power he remarked to a friend that "this buries the revolution" and described government members as "state socialists".

In June 1918, Kropotkin had a meeting with Nestor Makhno, the leader of the anarchists in the Ukraine. He told him about a conversation he had with Lenin in the Kremlin. Lenin explained his opposition to anarchists. "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them... But I think that you, comrade, have a realistic attitude towards the burning evils of the time. If only one-third of the anarchist-communists were like you, we Communists would be ready, under certain well-known conditions, to join with them in working towards a free organization of producers."

Kropotkin disliked the developments that took place over the next few months and in March 1920 he sent a letter to Lenin that claimed Russia was a "Soviet Republic only in name" and "at present it is not the soviets which rule in Russia but party committees".

Peter Kropotkin died of pneumonia in the city of Dmitrov on 8th February, 1921, and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. His friend, Victor Serge, attended the funeral. "These were heartbreaking days: the great frost in the midst of the great hunger. I was the only member of the party to be accepted as a comrade in anarchist circles. The shadow of the Cheka fell everywhere, but a packed and passionate multitude thronged around the bier, making this funeral ceremony into a demonstration of unmistakable significance." Kropotkin's final book, Ethics, Origin and Development (1922) was published posthumously.

On this day in 1869 Edith Craig, was born. Her parents, Edward William Godwin, an architect, and Ellen Terry, an actress, had eloped the previous year.

After her separation from Godwin in 1875, Ellen Terry was primary carer for Edith Craig and her brother Edward Craig. She was educated at Mrs Cole's school, a co-educational institution in Foxton Road, Earls Court and the Royal Academy of Music.

Craig became interested in the subject of women's suffrage after meeting Elizabeth Malleson when she was a child. She later recalled: "When I was at school I lived in a house of Suffrage workers, and at regular periods the task of organising Suffrage petitions kept everybody busy. Perhaps I didn't think very deeply about it, and my first ideas of Suffrage duties were concerned with the interminable addressing of envelopes; but I certainly grew up quite firmly certain that no self-respecting woman could be other than a Suffragist."

With the help of her mother she worked for the Lyceum Theatre company, designing costumes and acting under the stage name of Ailsa Craig and in 1895 appeared with Henry Irving in The Bells and Bygones, a play by Arthur Wing Pinero. Her performances were praised by George Bernard Shaw and later that year she made her first tour of America.

Edith Craig lived with the writer Christabel Marshall from 1899, when the two women shared a flat at 7 Smith Square, London. Despite her acting success, Edith Craig decided to start a business producing costumes for several London theatre productions. In 1902–3 she collaborated with the artist Pamela Colman Smith on the design of scenes for Where there is Nothing a play by W. B. Yeats. According to her biographer, Katharine Cockin: "Craig was an active member of several significant theatre societies which produced experimental drama in London; some of them directly challenged the lord chamberlain's regulation of the stage: the Independent Theatre; the Stage Society; the Masquers; the Pioneer Players; the Phoenix Society; and the Renaissance Theatre Society."

Ellen Terry claimed: "She (Edith Craig) loathes emotional people, yet adores me. I scarcely ever dare kiss her, and I'm always dying to, but she hates it from anyone." Christabel Marshall added: "I often felt that I had not the faintest notion of what was going on in her mind and heart and soul. She seldom talked about herself; she was as reticent on that subject as she was frank and explicit on others."

Edith Craig joined the Women's Social and Political Union and in 1908, some of the members formed the Actresses' Franchise League. Craig joined this group that at this time included Elizabeth Robins, Kitty Marion, Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Lena Ashwell, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault.

The first meeting of the Actresses' Franchise League took place at the Criterion Restaurant at Piccadilly Circus. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays. The AFL neither supported nor condemned militancy.

Inez Bensusan oversaw the writing, collection and publication of AFL plays. Pro-suffragette plays written by members of the Women Writers Suffrage League and performed by the AFL included the play How the Vote was Won by Cicely Hamilton and Votes for Women by Elizabeth Robins. Another play by Hamilton, A Pageant of Great Women, was directed by Edith Craig. She also acted in several of these plays.

Edith Craig sold the WSPU journal Votes for Women: "I love it. But I'm always getting moved on. You see, I generally sell the paper outside the Eustace Miles Restaurant, and I offer it verbally to every soul that passes. If they refuse, I say something to them. Most of them reply, others come up, and we collect a little crowd until I'm told to let the people into the restaurant, and move on. Then I begin all over again."

Craig, like many members of the WSPU, began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. Eventually, Craig, joined Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard as members of the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

Her close friend, Cicely Hamilton, argued: "I do not think that Edy (Edith Craig) shared these high hopes of a world reformed by the entry of women into politics; she was a feminist rather than politician and stood for the franchise chiefly as a measure of justice." Craig was a member of several women's suffrage organisations. When asked by Votes for Women in April 1910 if she was chief organiser of the Actresses' Franchise League she replied: "I organise for every society I belong to, not for any one in particular. That's nearer the truth... As to joining Suffrage societies - yes, I belong to ten now, but I don't seem to be able to remember more than seven." Lisa Tickner has argued that Craig was a "crucial link between the suffrage art and theatre organizations".

In 1910 Edith Craig joined forces with Sime Seruya, Ellen Terry and Cicely Hamilton to establish the International Suffrage Shop, a feminist publisher and bookseller, in the Strand. As Katharine Cockin has pointed out: "It was more of a cultural centre than a shop, organizing printing, book-binding, book searches, lectures and meetings and housing a lending library.

In 1911 Craig established the Pioneer Players. Under her leadership this society became internationally known for promoting women's work in the theatre. Ellen Terry was president of the Pioneer Players and Christabel Marshall contributed as dramatist, translator, actor and a member of the advisory and casting committees. One of the first productions of the group was In the Workhouse, a play written by Margaret Nevinson, one of the leaders of the Women's Freedom League (WFL). The play, based on a true story, told of how a man who used the law to keep his wife in the workhouse against her will. As a result of the play, the law was changed in 1912.

Craig openly called her productions, "propaganda plays". She argued that her plays played an important role in the struggle for women's suffrage: "I do think plays have done such a lot for the Suffrage. They get hold of naive frivolous people who would die sooner than go in cold blood to meetings. But they see the plays, and get interested, and then we can rope them in for meetings. All Suffrage writers ought to write Suffrage plays as hard as they can. It's a great work."

Christabel Marshall wrote about her relationship with Craig in her journal, The Golden Book (1911), and in her anonymously published second novel, Hungerheart: the Story of a Soul (1915). In 1916 Clare Atwood moved into the flat at 31 Bedford Street, Covent Garden, that she shared with Christabel Marshall, forming a permanent ménage à trois. Her biographer, Katharine Cockin, has pointed out that Marshall wrote they "achieved independence within their intimate relationships... working respectively in the theatre, art, and literature, drew creative inspiration and support from each other."

Nina Auerbach has argued: "Edith Craig has not the famous Terry charm; indeed, at first glance she seems almost hard and forbidding. But that she possesses a charm of her own is undeniable; it lies deeper and is more sweeping in its effect upon those it captivates. I know quite a number of women who would unhesitatingly lay down their lives for Edith Craig. She is not only their friend and teacher, but their very goddess. Edith Craig's influence upon many of the younger artists of the stage is more far-reaching than the public would suppose. Like her celebrated brother, however, she seems fated to do the greater and more important part of her life's work away from the searching limelight."

Craig also developed links with the Provincetown Theatre Group in America and in 1919 the Pioneer Players performed the play, Trifles, that had been written by Susan Glaspell in 1916. It has been argued that the play, based on the John Hossack case, is an example of early feminist drama. Heywood Broun was one of those who saw the significance of the play: "No direct statements are made for the benefit of the audience. Like the women, they must piece out the story by inference... The story is brought to mind vividly enough to induce the audience to share the sympathy of the women for the wife and agree with them that the trifles which tell the story should not be revealed." She also produced Glaspell's The Verge in 1925.

In the 1920s she directed plays for the Everyman Theatre in Hampstead and worked as art director for Leeds Art Theatre. Other notable productions by Craig included Hugo von Hofmannstahl's The Great World Theatre (1924); the first modern production of John Webster's The White Devil (1925); and George Bernard Shaw's Back to Methuselah (1930).

After the death of Ellen Terry in 1928, Edith Craig converted the barn in the grounds of her mother's house in Smallhythe Place, Tenterden, into a theatre. Craig's home next door, The Priest's House, became an important cultural centre that was visited by Radclyffe Hall, Una Troubridge, Vera Holme, Vita Sackville West and Virginia Woolf.

Edith Craig died of coronary thrombosis and chronic myocarditis on 27th March 1947. According to Katharine Cockin, the author of Edith Craig (1998), Christabel Marshall destroyed all her "papers (and presumably the memoirs)" after Craig's death.

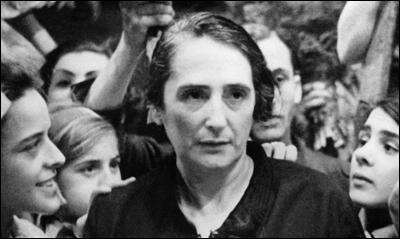

On the day in 1895 Dolores Ibárruri, the eighth of eleven children, was born in Gallarta, Spain, on 9th December, 1895. Ibárruri was born into a family of miners, Ibárruri experienced poverty as a child. Although an intelligent student, her family could not afford to pay for her to be trained as a teacher and instead became a seamstress.

In 1916 she married a miner and had six children but only two survived to adulthood. She later wrote that they had died because of her inability to provide adequate medical care and nourishment for them.

The family's financial situation deteriorated when her husband, an active trade unionist, was imprisoned for leading a strike. After reading the works of Karl Marx, Ibárruri joined the Communist Party (PCE). Ibárruri wrote articles for the miners' newspaper, El Minero Vizcaino, using the pseudonym Pasionaria (passion flower).

In 1920 Ibárruri was elected to the Provincial Committee of the Basque Communist Party. She soon became an important local political figure and in 1930 was elected to the Central Committee of the Spanish Communist Party. The following year she became editor of the left-wing newspaper, Mundo Obrero. Over the next few years she used her position to campaign for an improvement in women's conditions in Spain.

In September 1931 Ibárruri was arrested and charged with hiding a Communist comrade on the run from the Civil Guard. After being held in prison in Bilbao she was released in January 1932. She was then re-arrested and held in prison until January 1933.

Ibárruri was a member of the Spanish delegation of the Communist International which met in the Soviet Union in 1933. She also attended meetings of the Comintern where she supported what became known as the Popular Front policy.

Concerned by the emergence of fascism in Italy and Germany, Ibárruri helped organize the World Committee of Women Against War and Fascism and was a delegate at its first conference in France in August 1934.

In 1936 Ibárruri, now known by everybody as (La Pasionaria), was elected to the Cortes. During the first few months as a deputy she campaigned for legislation to improve working, housing and health conditions. She also sought land reform and rights for trade unionists. Ibárruri also successfully negotiated the release of several political prisoners in Spain.

During the Spanish Civil War Ibárruri was the chief propagandist for the Republicans. On 18th July, 1936, she ended a radio speech with the words: "The fascists shall not pass! No Pasaran". This phrase eventually became the battle cry for the Republican Army. In another speech she declared at a meeting for women: "It is better to be the widows of heroes than the wives of cowards!"

In September 1936 Ibárruri was sent to France and Belgium to rally support for the Republic. At one meeting she used the phrase "the Spanish people would rather die on its feet than live on its knees." She became a member of the committee designated to administer funds sent to Spain by the Comintern. Ibárruri was also involved in the destruction of the Worker's Party (POUM) and the dismissal of Francisco Largo Caballero and Juan Peiro from the government and supported the appointment of Juan Negrin as prime minister.

At the end of the war Ibárruri fled to the Soviet Union. Her only son, Ruben Ibárruri fought for the Red Army during the Second World War and was killed at Stalingrad on 3rd December 1942.

Ibárruri became Secretary General of the Communist Party (PCE) in May 1944. After the war she remained in Moscow and in 1964 was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize and the following year the Order of Lenin. However, in 1968 she strongly attacked the Red Army invasion of the Czechoslovakia. The Russian leadership responded by sponsoring a breakaway Spanish Communist Party led by Enrique Lister.

After the death of Francisco Franco Ibárruri returned to Spain and in 1977 was elected deputy to the Cortes. Aged 93, Dolores Ibarruri died of pneumonia on 12th November, 1989.

On this day in 1909 Charlotte Marsh left prison after been forced fed by tube 139 times. Charlotte Marsh, the daughter of Arthur Hardwick Marsh (1842-1909), an artist, was born in 1887. She was educated at St Margaret's School, Newcastle upon Tyne, and Roseneath, Wrexham, and then spent a year studying in Bordeaux.

Marsh joined the Women Social & Political Union in March 1907 but did not become an active member until she finished her training as a sanitary inspector a year later. According to her biographer, Michelle Myall: "She was one of the first women to train as a sanitary inspector but, appalled by the insight her work gave her into the lives of many women, gave up a promising career to join the women's suffrage movement in 1908, to give women a voice in public affairs." On 30th June 1908 she was arrested with Elsie Howey and charged with obstructing the police. She was found guilty and sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Holloway Prison.

A wealthy supporter of the WSPU donated money to buy Emmeline Pankhurst a motor car so that she could travel the country in comfort. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001), Marsh applied for the job of driving the car. However, Vera Holme, got the post, but there were occasions when she worked as Pankhurst's chauffeur.

On 22nd September 1909 she was arrested along with Rona Robinson, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. As Michelle Myall has pointed out: "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."

On 22nd September 1909 she was arrested along with Rona Robinson, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. As Michelle Myall has pointed out: "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."

Marsh, Robinson, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

C.P. Scott wrote to Asquith complaining of the "substantial injustice of punishing a girl like Miss Marsh with two months hard labour plus forcible feeding." According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "The Prison Visiting Committee reported that at first she had to be fed by placing food in the mouth and holding the nostrils, but that she later took food from a feeding cup." Votes for Women, on her release, reported that she had been fed by tube 139 times. Although her father was seriously ill, the authorities refused to release Marsh early. Marsh left Winson Green Prison on 9th December, 1909. She immediately dashed to her family home in Newcastle upon Tyne but he was already unconscious and he died a few days later.

In February 1910 Charlotte Marsh was WSPU organiser in Oxford. She then moved onto Portsmouth and in September 1910 she ran a WSPU holiday campaign in Southsea. During this period a fellow suffragette described her as "a tall young woman, of quiet, resolute bearing." The Times reported that she was "strikingly beautiful with blue eyes and long corn-coloured hair." Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence described her as one of the "saints of the Church Militant".

Marsh visited Eagle House near Batheaston in April 1911 with Annie Kenney and Laura Ainsworth. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Picea Polita, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. Mary's mother, Emily Blathwayt, commented in her diary: "Miss Marsh planted her tree. She greatly dislikes her first name Charlotte and all her friends call her Charlie. Her label will be C. A. L. Marsh. (She also goes by the name of Calm). We liked very much what we saw of her. She is very fair with light hair and a pretty face. She is very tall ... She has a wonderful constitution and seems very well after all she has gone through. She has begun the late custom of not taking meat or chicken. She seems a very nice quiet girl."

In March 1912 Charlotte Marsh took part in a window-smashing campaign in London. It is claimed that she alone smashed nine windows in the Strand during this demonstration. Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "Linley had a nice letter from C. A. L. Marsh in Holloway awaiting her trial as they all refused bail. His birthday letter to her begging her not to take part in violence followed her there. Like the rest, they all think it their duty to take a large share of suffering." As she had previous convictions she was sentenced to six months' in Aylesbury Prison. She took part in the hunger-strike and was forcibly fed.

On her release she was sent to Switzerland to recuperate. On her return she was WSPU organiser in Nottingham. She also spent time in London working alongside Grace Roe. In June 1913 she was the Standard Bearer at the funeral of Emily Wilding Davison.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Charlotte Marsh initially accepted this policy and worked as a motor mechanic before becoming the chauffeur of David Lloyd George "accepting his suggestion that the relationship would promote the victory of the cause of women's enfranchisement". She also worked as a member of the Women's Land Army in Surrey.

Marsh became increasingly critical of the way that Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were running the WSPU during the First World War. Questions were also being asked about the funds of the WSPU. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001): "The accounts had not been rendered since February 1914 when an annual income of £46,000 had been recorded. Moreover, the conviction that this money had been misappropriated for the Pankhursts' own purposes continued to rankle for many years." In March 1916, Charlotte Marsh set up the Independent WSPU.

After the war Marsh worked for Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. According to Elizabeth Crawford: "She then spent some time with the Department of Social Work in San Francisco and then with the Overseas Settlement League. By 1934 she was working with the Public Assistance Department of the London County Council." Marsh was also, along with Margaret Haig Thomas and Theresa Garnett, an executive member of the Six Point Group. She was also vice-president of the Suffragette Fellowship. Charlotte Marsh, who never married, died at her home, 31 Copse Hill, Wimbledon, on 21st April 1961.

On this day in 1917 was the last day of voting for the Russian Constituent Assembly. After Nicholas II abdicated, the new Provisional Government announced it would introduce a Constituent Assembly. Elections were due to take place in November. Some leading Bolsheviks believed that the election should be postponed as the Socialist Revolutionaries might well become the largest force in the assembly. When it seemed that the election was to be cancelled, five members of the Bolshevik Central Committee, Victor Nogin, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Vladimir Milyutin submitted their resignations.

Kamenev believed it was better to allow the election to go ahead and although the Bolsheviks would be beaten it would give them to chance to expose the deficiencies of the Socialist Revolutionaries. "We (the Bolsheviks) shall be such a strong opposition party that in a country of universal suffrage our opponents will be compelled to make concessions to us at every step, or we will form, together with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, non-party peasants, etc., a ruling bloc which will fundamentally have to carry out our programme."

On 4th November, 1917, the five men issued a statement: "The leading group in the Central Committee... has firmly decided not to allow the formation of a government of the soviet parties but to fight for a purely Bolshevik government however it can and whatever the sacrifices this costs the workers and soldiers. We cannot assume responsibility for this ruinous policy of the Central Committee, carried out against the will of a large part of the proletariat and soldiers." Nogin, Rykov, Milyutin and Ivan Teodorovich resigned their commissariats. They issued another statement: "There is only one path: the preservation of a purely Bolshevik government by means of political terror. We cannot and will not accept this."

Eventually it was decided to go ahead with the elections for the Consistent Assembly. The party newspaper, Pravda, claimed: "As a democratic government we cannot disregard the decision of the people, even if we do not agree with it. If the peasants follow the Social Revolutionaries farther, even if they give that party a majority in the Constituent Assembly, we shall say: so be it."

Eugene Lyons, the author of Workers’ Paradise Lost: Fifty Years of Soviet Communism: A Balance Sheet (1967), pointed out: "The hopes of self-government unleashed by the fall of tsarism were centered on the Constituent Assembly, a democratic parliament to draw up a democratic constitution. Lenin and his followers, of course, jumped on that bandwagon, too, posing not merely as advocates of the parliament but as its only true friends. What if the voting went against them? They piously pledged themselves to abide by the popular mandate."

The balloting began on 25th November and continued until 9th December. Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, reported: "The elections for the Constituent Assembly have just taken place here. The polling was very high. Every man and woman votes all over this vast territory, even the Lapp in Siberia and the Tartar of Central Asia. Russia is now the greatest and most democratic country in the world. There are several women candidates for the Constituent Assembly and some are said to have a good chance of election. The one thing that troubles us all and hangs like a cloud over our heads is the fear of famine."

Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17).

The elections disclosed the strongholds of each party: "The Socialist-Revolutionaries were dominant in the north, north-west, central black earth, south-eastern Volga, in the north Caucasus, Siberia, most of the Ukraine and amongst the soldiers of the south-western and Rumanian fronts, and the sailors of the Black Sea fleet. The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, held sway in White Russia, in most of the central provinces, and in Petrograd and Moscow. They also dominated the armies on the northern and western fronts and the Baltic fleet. The Mensheviks were virtually limited to Transcaucasia, and the Kadets to the metropolitan centres of Moscow and Petrograd where, in any case, they took place to the Bolsheviks."

It seemed that the Socialist Revolutionaries would be in a position to form the next government. As David Shub pointed out, "The Russian people, in the freest election in modern history, voted for moderate socialism and against the bourgeoisie." Most members of the Bolshevik Central Committee, now favoured a coalition government. Lenin believed that the Bolsheviks should retain power and attacked his opponents for their "un-Marxist remarks" and their criminal vacillation". Lenin managed to pass a resolution through the Central Committee by a narrow margin.

Lenin demobilized the Russian Army and announced that he planned to seek an armistice with Germany. In December, 1917, Leon Trotsky led the Russian delegation at Brest-Litovsk that was negotiating with representatives from Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread from Russia to Germany and Austria-Hungary before he had to sign the treaty.

The Constituent Assembly opened on 18th January, 1918. "The Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries occupied the extreme left of the house; next to them sat the crowded Socialist Revolutionary majority, then the Mensheviks. The benches on the right were empty. A number of Cadet deputies had already been arrested; the rest stayed away. The entire Assembly was Socialist - but the Bolsheviks were only a minority."