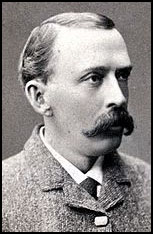

George Kennan

George Kennan, the son of Scotch-Irish pioneers, was born in Norfolk, Ohio, on 16th February, 1845. At the age of twelve he left school and found work at the Western Union telegraph office. According to his relative, George Frost Kennan, he was "too frail to serve in uniform" during the American Civil War.

Kennan moved to Cincinnati, where he was appointed to the post of assistant chief operator for Western Union and as military telegrapher for the Associated Press. In 1864, at the age of nineteen, he successfully applied to become a member of an Alaskan-Siberian expedition. The objective being to lay a telegraph line over Alaska and Siberia to connect with the the eastern-most terminus of the Russian telegraph system, at Irkutsk.

On 1st July, 1865, Kennan and three companions set out from San Francisco in a Russian brig. His biographer claims: "Eight weeks later two of them, Kennan and a Russian major, were set ashore at Petropavlovsk, on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Their instructions were to make their way northward through the peninsula to the mainland of eastern Siberia, where they were to explore the two thousand miles of inhospitable territory lying between the Anadyrsk region on the Bering Sea and Nikolayevsk-on-the-Amur and to arrange for the laying of the telegraph line. They were to be picked up a year or so later, after surveying a line and having camps laid out and poles cut for the construction workers who would follow them. Meanwhile they would be on their own. By a combination of good fortune, level-headedness, and physical courage young Kennan, then only twenty years old, survived this ordeal. Dressed like a native, leading the primitive and arduous life of the wandering tribes of that area, traveling at times, for weeks on end, alone with a Yakut dog team through the wastes of one of the world's most forbidding Arctic regions, he completed his assignment. When the relief ship finally arrived, it brought the news that the Atlantic cable had been laid and the entire project had been in vain."

After arriving back in the United States he worked for banks and law offices. Kennan also lectured on his Siberian experiences. Eventually, he moved to Washington where he became night manager of the Associated Press. In 1870 G. P. Putnam's Sons published an account of the Siberian adventures under the title Tent Life in Siberia. According to George Frost Kennan: "It was a creditable literary achievement, especially for a young man without high school or college education. The style, like that of everything Kennan subsequently wrote, was straightforward, clear and disciplined."

On 1st March, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by members of the People's Will. The following month Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Gesia Gelfman and Timofei Mikhailov were executed for their involvement in the assassination. Others such as Gesia Gelfman, Olga Liubatovich, Anna Yakimova, Vera Figner, Grigory Isaev, Mikhail Frolenko, Tatiana Lebedeva and Anna Korba were exiled to Siberia.

Kennan attempted to obtain sponsorship for and on-the-spot study of Siberia and the exile system. After approaching several organizations he eventually persuaded Century Magazine to finance the expedition. After a preliminary visit to St. Petersburg and Moscow to perfect the arrangements, Kennan set off on his journey in the early spring of 1885, accompanied by the artist, George Albert Frost. "We both spoke Russian, both had been in Siberia before, and I was making to the empire my fourth journey."

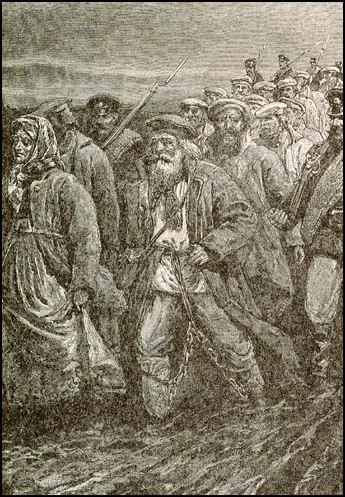

The account of the journey appeared serially, in the years 1888-89, in Century Magazine. In an early article he explained the tradition of sending criminals to Siberia. "Russian exiles began to go to Siberia very soon after its discovery and conquest - as early probably as the first half of the seventeenth century. The earliest mention of exile in Russian legislation is in a law of the Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in 1648. Exile, however, at that time, was regarded not as a punishment in itself, but as a means of getting criminals who had already been punished out of the way. The Russian criminal code of that age was almost incredibly cruel and barbarous. Men were impaled on sharp stakes, hanged, and beheaded by the hundred for crimes that would not now be regarded as capital in any civilized country in the world; while lesser offenders were flogged with the knut and bastinado, branded with hot irons, mutilated by amputation of one or more of their limbs, deprived of their tongues, and suspended in the air by hooks passed under two of their ribs until they died a lingering and miserable death."

Kennan explained that it was the case of Vera Zasulich when she tried to assassinate Dmitry Trepov, the Governor General of St. Petersburg, that encouraged Tsar Alexander II to send political prisoners to Siberia. This included those distributing political propaganda to the peasants. "They... did not resort to violence in any form, and did not even make a practice of resisting arrest, until after the Government had begun to exile them to Siberia for life with ten or twelve years of penal servitude, for offenses that were being punished at the very same time in Austria with only a few days - or at most a few weeks - of personal detention. It was not terrorrism that necessitated administrative exile in Russia; it was merciless severity and banishment without due process of law that provoked terrorism."

Kennan interviewed several of those political prisoners. This included Anna Korba a member of the People's Will. "In 1877 the Russo-Turkish War broke out, and opened to her ardent and generous nature a new field of benevolent activity. As soon as wounded Russian soldiers began to come back from Bulgaria, she went into the hospitals of Minsk as a Sister of Mercy, and a short time afterward put on the uniform of the International Association of the Red Cross, and went to the front and took a position as a Red Cross nurse in a Russian field-hospital beyond the Danube. She was then hardly twenty-seven years of age. What she saw and what she suffered in the course of that terrible Russo-Turkish campaign can be imagined by those who have seen the paintings of the Russian artist Vereshchagin. Her experience had a marked and permanent effect upon her character. She became an enthusiastic lover and admirer of the common Russian peasant, who bears upon his weary shoulders the whole burden of the Russian state, but who is cheated, robbed, and oppressed, even while fighting the battles of his country. She determined to devote the remainder of her life to the education and the emancipation of this oppressed class of the Russian people. At the close of the war she returned to Russia, but was almost immediately prostrated by typhus fever contracted in an overcrowded hospital. After a long and dangerous illness she finally recovered, and began the task that she had set herself; but she was opposed and thwarted at every step by the police and the bureaucratic officials who were interested in maintaining the existing state of things, and she gradually became convinced that before much could be done to improve the condition of the common people the Government must be overthrown. She... participated actively in all the attempts that were made between 1879 and 1882 to overthrow the autocracy and establish a constitutional form of government." She was arrested and found guilty of carrying out propaganda activities and was sent to the Kara Prison Mines in Siberia.

Kennan carried out a long interview with Prince Alexander Kropotkin, the brother of Prince Peter Kropotkin. Kennan pointed out that: "Prince Alexander Kropotkin's... views with regard to social and political questions would have been regarded in America, or even in western Europe, as very moderate, and he had never taken any part in Russian revolutionary agitation. He was, however, a man of impetuous temperament, high standard of honor, and great frankness and directness of speech; and these characteristics were perhaps enough to attract to him the suspicious attention of the Russian police."

Kropotkin told Kennan: "I am not a nihilist nor a revolutionist and I never have been. I was exiled simply because I dared to think, and to say - what I thought, about the things that happened around me, and because I was the brother of a man whom the Russian Government hated." His first arrest was as a result of having a copy of a book, Self-Reliance, by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Kennan had great respect for Kropotkin and was distressed when he heard about how he committed suicide while in exile in 1890.

In 1891 his articles were published in book form under the title Siberia and the Exile System. The book appeared illegally in Russia and according to George Frost Kennan: "The gratitude of the entire opposition movement-moderates and extremists alike - went out to him for his profound understanding and effective public sponsorship of the opposition cause."

Kennan served as a war correspondent in the Spanish-American War and the Russo-Japanese War. When Tsar Nicholas II abdicated he gave his support to the Provisional Government led by Prince George Lvov and Alexander Kerensky. He disapproved of the Bolshevik Revolution but argued against USA intervention in the Russian Civil War.

George Kennan died in 1924.

Primary Sources

(1) George Frost Kennan, George Kennan (1891)

The first attempt to lay an Atlantic cable had, at this juncture, only recently been made. Its failure had caused discouragement over the prospects for any underwater telegraph connection between Europe and America. The Western Union Company had turned, as an alternative, to the possibility of laying a telegraph line over Alaska and Siberia, to connect with the easternmost terminus of the Russian telegraph system, at Irkutsk. The expedition in which Kennan was to participate was mounted to implement this project. The young telegrapher had already invested his savings in the expedition before he applied for and received his appointment to it, and his pluck apparently impressed the superintendent of the company.

On July 1, 1865, Kennan and three companions set out from San Francisco in the Russian brig "Olga." Eight weeks later two of them, Kennan and a Russian major, were set ashore at Petropavlovsk, on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Their instructions were to make their way northward through the peninsula to the mainland of eastern Siberia, where they were to explore the two thousand miles of inhospitable territory lying between the Anadyrsk region on the Bering Sea and Nikolayevsk-on-the-Amur and to arrange for the laying of the telegraph line. They were to be picked up a year or so later, after surveying a line and having camps laid out and poles cut for the construction workers wvho would follow them. Meanwhile they would be on their own.

By a combination of good fortune, level-headedness, and physical courage young Kennan, then only twenty years old, survived this ordeal. Dressed like a native, leading the primitive and arduous life of the wandering tribes of that area, traveling at times, for weeks on end, alone with a Yakut dog team through the wastes of one of the world's most forbidding Arctic regions, he completed his assignment. When the relief ship finally arrived, it brought the news that the Atlantic cable had been laid and the entire project had been in vain.

(2) George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System (1891)

To a traveler visiting Nizhni Novborod for the first time there is something surprising, and almost startling, in the appearance of what he supposes to be the city, and in the scene presented to him as he emerges from the railway_ station and walks away from the low bank of the Okla River in the direction of the Volga. The clean, well-paved streets; the long rows of substantial buildings; the spacious boulevard, shaded by leafy birches and poplars; the canal, spanned at intervals by graceful bridges; the picturesque tower of the water-works; the enormous cathedral of Alexander Nevski; the Bourse; the theaters; the hotels; the market places-all seem to indicate a great populous center of life and commercial activity; but of living inhabitants there is not a sign. Grass and weeds are growing in the middle of the empty streets and in the chinks of the travel-worn sidewalks; birds are singing fearlessly in the trees that shade the lonely and deserted boulevard; the countless shops and warehouses are all closed, barred, and padlocked; the bells are silent in the gilded belfries of the churches; and the astonished stranger may perhaps wander for a mile between solid blocks of buildings without seeing an open door, a vehicle, or a single human being. The city appears to have been stricken by a pestilence and deserted. If the newcomer remembers for what Nizhni Novgorod is celebrated, he is not long, of course, in coming to the conclusion that he is on the site of the famous fair; but the first realization of the fact that the fair is in itself a separate and independent city, and a city that during nine months of every year stands empty and deserted, comes to him with the shock of great surprise.

(3) George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System (1891)

Russian exiles began to go to Siberia very soon after its discovery and conquest - as early probably as the first half of the seventeenth century. The earliest mention of exile in Russian legislation is in a law of the Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in 1648. Exile, however, at that time, was regarded not as a punishment in itself, but as a means of getting criminals who had already been punished out of the way. The Russian criminal code of that age was almost incredibly cruel and barbarous. Men were impaled on sharp stakes, hanged, and beheaded by the hundred for crimes that would not now be regarded as capital in any civilized country in the world; while lesser offenders were flogged with the knut and bastinado, branded with hot irons, mutilated by amputation of one or more of their limbs, deprived of their tongues, and suspended in the air by hooks passed under two of their ribs until they died a lingering and miserable death.

When criminals had been thus knuted, bastinadoed, branded, or crippled by amputation, Siberian exile was resorted to as a quick and easy method of getting them out of the way; and in this attempt to rid society of criminals who were both morally and physically useless Siberian exile had its origin. The amelioration, however, of the Russian criminal code, which began in the latter part of the seventeenth century, and the progressive development of Siberia itself gradually brought about a change in the view taken of Siberian exile. Instead of regarding it, as before, as a means of getting rid of disabled criminals, the Government began to look upon it as a means of populating and developing a new and promising part of its Asiatic territory. Toward the close of the seventeenth century, therefore, we find a number of ukazes abolishing personal mutilation as a method of punishment, and substituting for it, and in a large number of cases even for the death penalty, the banishment of the criminal to Siberia with all his family. About the same time exile, as a punishment, began to be extended to a large number of crimes that had previously been punished in other ways; as, for example, desertion from the army, assault with intent to kill, and vagrancy when the vagrant was unfit for military service and no land owner or village commune would take charge of him. Men were exiled, too, for almost every conceivable sort of minor offense, such, for instance, as fortune-telling, prize-fighting, snuff-taking, driving with reins, begging with a pretense of being in distress, and setting fire to property accidentally.

In the eighteenth century the great mineral and agricultural resources of Siberia began to attract to it the serious and earnest attention of the Russian government. The discovery of the Daurski silver mines, and the rich mines of Nerchinsk in the Siberian territory of the Trans-Baikal, created a sudden demand for labor, which led the government to promulgate a new series of ukazes providing for the transportation thither of convicts from the Russian prisons. In 1762 permission was given to all individuals and corporations owning serfs, to hand the latter over to the local authorities for banishment to Siberia whenever they thought they had good reason for so doing. With the abolition of capital punishment in 1753, all criminals that, under the old law, would have been put to death, were condemned to perpetual exile in Siberia with hard labor.

(4) George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System (1891)

The first attempt on the part of the terrorists to assassinate a Government official was the attempt of Vera Vasulich to kill General Trepof, the St. Petersburg chief of police, on the 5th of February, 1878. Administrative exile for political reasons had then been common for almost a decade. If I mistake not, Vera Zasulich herself had been one of its victims seven or eight years before. I think she was one of twenty or thirty persons who were tried before a special session of the Governing Senate in 1871 upon the charge of complicity in the Nechaief conspiracy, who were judicially declared to be not guilty, but who were immediately rearrested, nevertheless, and exiled by administrative process, in defiance of all law and in contemptuous disregard of the judgment of the highest court in the empire. A government that acts in this way sows dragons' teeth and has no right to complain of the harvest. The so-called "propagandists" of 1870-74 did not resort to violence in any form, and did not even make a practice of resisting arrest, until after the Government had begun to exile them to Siberia for life with ten or twelve years of penal servitude, for offenses that were being punished at the very, same time in Austria with only a few days - or at most a few weeks - of personal detention. It was not terrorrism that necessitated administrative exile in Russia; it was merciless severity and banishment without due process of law that provoked terrorism.

(5) George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System (1891)

In 1870 her husband failed in business: she was forced to abandon the hope of finishing her collegiate training abroad, and a short time afterward went with her husband to reside in the small provincial town of Minsk, where he had obtained employment. Here she began her career of public activity by organizing a society and raising a fund for the purpose of promoting popular education and aiding poor students in the universities. Of this society she was the president. In 1877 the Russo-Turkish War broke out, and opened to her ardent and generous nature a new field of benevolent activity. As soon as wounded Russian soldiers began to come back from Bulgaria, she went into the hospitals of Minsk as a Sister of Mercy, and a short time afterward put on the uniform of the International Association of the Red Cross, and went to the front and took a position as a Red Cross nurse in a Russian field-hospital beyond the Danube. She was then hardly twenty-seven years of age. What she saw and what she suffered in the course of that terrible Russo-Turkish campaign can be imagined by those who have seen the paintings of the Russian artist Vereshchagin. Her experience had a marked and permanent effect upon her character. She became an enthusiastic lover and admirer of the common Russian peasant, who bears upon his weary shoulders the whole burden of the Russian state, but who is cheated, robbed, and oppressed, even while fighting the battles of his country. She determined to devote the remainder of her life to the education and the emancipation of this oppressed class of the Russian people. At the close of the war she returned to Russia, but was almost immediately prostrated by typhus fever contracted in an overcrowded hospital. After a long and dangerous illness she finally recovered, and began the task that she had set herself; but she was opposed and thwarted at every step by the police and the bureaucratic officials who were interested in maintaining the existing state of things, and she gradually became convinced that before much could be done to improve the condition of the common people the Government must be overthrown. She soon afterward became a revolutionist, joined the party of "The Will of the People," and participated actively in all the attempts that were made between 1879 and 1882 to overthrow the autocracy and establish a constitutional form of government.

(6) George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System (1891)

Although banished to Siberia upon the charge of disloyalty Kropotkin was not a nihilist, nor a revolutionist, nor even an extreme radical. His views with regard to social and political questions would have been regarded in America, or even in western Europe, as very moderate, and he had never taken any part in Russian revolutionary agitation. He was, however, a man of impetuous temperament, high standard of honor, and great frankness and directness of speech; and these characteristics were perhaps enough to attract to him the suspicious attention of the Russian police.

"I am not a nihilist nor a revolutionist," he once said to me indignantly, "and I never have been. I was exiled simply because I dared to think, and to say - what I thought, about the things that happened around me, and because I was the brother of a man whom the Russian Government hated."

Prince Kropotkin was arrested the first time in 1858, while a student in the St. Petersburg University, for having in his possession a copy in English of Emerson's Self-Reliance and refusing to say where he obtained it. The book had been lent to him by one of the faculty, Professor Tikhonravof, and Kropotkin might perhaps have justified himself and escaped unpleasant consequences by simply stating the fact; but this would not have been in accordance with his high standard of personal honor. He did not think it a crime to read Emerson, but he did regard it as cowardly and dishonorable to shelter himself from the consequences of any action behind the person of an instructor. He preferred to go to prison. When Professor Tikhonravof heard of Kropotkin's arrest he went at once to the rector of the university, and admitted that he was the owner of the incendiary volume, and the young student was thereupon released.