On this day on 9th January

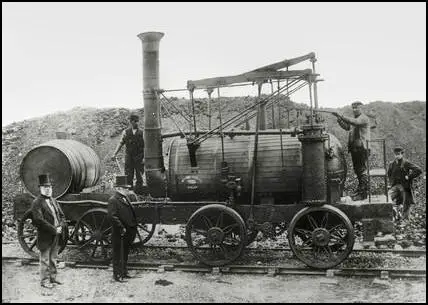

On this day in 1843, William Hedley died. Hedley was born at Newburn, near Newcastle-on-Tyne on 13th July, 1779. He became a manager at Walbottle Colliery before he was twenty-two. He afterwards held the same position at Wylam Colliery. Christopher Blackett, the owner of Wylam Colliery, had been interested in using locomotives for sometime. In 1804 he had employed Richard Trevithick to produce a locomotive that would replace the use of horse-drawn coal wagons. The Wylam Dilly locomotive was built, but weighing five tons, it was too heavy for Blackett's wooden wagonway.

In 1808 Christopher Blackett replaced his wooden rails with cast-iron plate-rails. Soon afterwards he asked Hedley, his colliery manager, to try and produce a steam locomotives. Hedley was helped in his task by two talented craftsman, Jonathan Foster, an enginewright, and Timothy Hackworth, a blacksmith. Hedley believed that if the wheels of the locomotive were coupled, the weight of a locomotive alone would provide sufficient adhesion, even where smooth wheels ran on smooth rails, to haul a train of loaded wagons. Hedley's theory was supported by his experiments and in 1813 he obtained a patent for his smooth rail system. Soon afterwards smooth rails were laid down at Wylam.

Hedley now turned his attention to designing and making a reliable locomotive. By 1814 he produced a locomotive that had two vertical cylinders outside the boiler. Piston rods extended upwards to pivotted beams, which were in turn connected by rods to a crankshaft beneath the frames, from which gears drove and also coupled the wheels. Originally carried on four wheels, the 8 ton locomotives were two heavy for the plate rails, and so to spread the weight on the templates, they were redesigned with eight wheels. Two of the locomotives produced by William Hedley, Jonathan Foster and Timothy Hackworth, were still working at Wylam Colliery in 1860. This included Puffing Billy and Wylam Dilly.

In 1828 William Hedley began renting the South Moor Colliery. While there he developed a steam-powered machine that improved the system of pumping water out of the mine. This steam-pump was soon used in collieries all over the North of England. Hedley died at Burnhopeside Hall, near Durham, on 9th January, 1843.

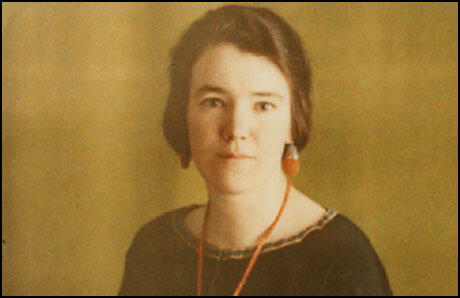

On this day in 1859 Carrie Chapman Catt was born. Carrie Lane was born in Wisconsin in 1860. She studied law at Iowa State College and after graduating became a superintendent of schools in Mason City (1883-84). She married the publisher, Lee Chapman, in 1884 but he died two years later.

Carrie had gradually developed feminist views and in 1890 became a state organizer for the Iowa Women's Suffrage Association. Soon after this she married George Catt, an engineer from Seattle. Catt agreed with Carrie's political views and signed a contract agreeing that she could devote half of each year to the campaign for women's suffrage.

At the end of the 19th century Catt emerged as one of the leaders of the women's suffrage movement and in 1900 was elected president of the National Woman Suffrage Association. A committed pacifist, Catt with her friend, Jane Addams, formed the Women's Peace Party.

Catt's dynamic leadership helped to bring about the 19th Amendment in 1920 that secured the vote for women. Carrie Chapman Catt continued to campaign for women's rights and world peace until her death on 9th March 1947.

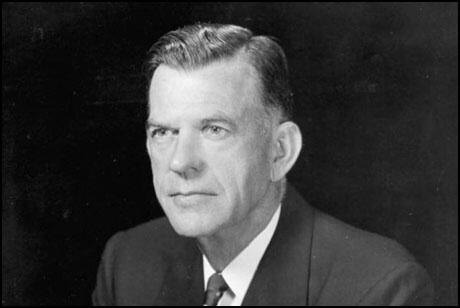

On this day in 1869 Noel Buxton, the second son of Thomas Fowell Buxton, was born in London. He grew up in the family house of Warlies Park House in Upshire, in a family of ten children.

Buxton was educated at Harrow School and Trinity College (1886–9). At Cambridge University he gained a third in the historical tripos. In 1889 he went to work at the family brewery in Spitalfields. He was shocked by the poverty he encountered and became involved in social work through the settlement movement.

He joined the Liberal Party and in 1897 he became a member of the Whitechapel board of guardians. He also contributed an essay on the problems of city life, to The Heart of the Empire, a book edited by Charles F. G. Masterman. In 1900 General Election he was unsuccessful in his first parliamentary contest in Ipswich, but was elected to parliament for Whitby at a by-election in 1905, only to be voted out again the following year in the the 1906 General Election.

Buxton was elected Liberal MP for North Norfolk in January 1910, and while campaigning in the constituency he met his future wife, Lucy Edith Burn at the time she was canvassing on behalf of his political opponent. The couple moved to Paycockes, a house at Coggeshall in Essex.

He supported Britain's involvement in First World War and even voted for conscription. However, he argued that "the prosecution of the war should be conducted in the diplomatic field as well." After the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in Russia, socialists in Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, United States and Italy called for a conference in a neutral country to see if the First World War could be brought to an end. Eventually, it was announced that the Stockholm Conference would take place in July 1917. Arthur Henderson was sent by David Lloyd-George to speak to Alexander Kerensky, the leader of the Provisional Government in Russia. However, under pressure from President Woodrow Wilson, the British government had changed his mind about the wisdom of the conference and refused to allow delegates to travel to Stockholm. As a result of this decision, Henderson resigned from the government.

Noel Buxton became very disillusioned with these developments and he now joined the Labour Party. His biographer, C. V. J. Griffiths has argued: "His social conscience and commitment to charitable work remained constant features in his life, and from 1919 onwards he directed part of his income to the achievement of social and economic progress through a special trust administered by the family."

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. MacDonald had the problem of forming a Cabinet with colleagues who had little, or no administrative experience. MacDonald's appointments included Buxton as Minister of Agriculture. A post he held until the fall of the MacDonald government in October, 1924.

In the 1929 General Election the Labour Party won 288 seats, making it the largest party in Parliament. MacDonald became Prime Minister again, but as before, he still had to rely on the support of the Liberals to hold onto power. Buxton became Minister of Agriculture in the new government.

Buxton retired from the House of Commons on medical advice in June 1930. However, he agreed to take the title Baron Noel-Buxton of Aylsham, Norfolk, on 17 June 1930.

Baron Noel-Buxton was chairman of the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society, president of the Save the Children Fund (1930-1948) and president of the Miners Welfare Fund (1931-1934). He was a supporter of appeasement, arguing that Germany must be given a colonial role in Africa. During the Second World War he promoted the policy of a negotiated peace with Nazi Germany.

Baron Noel Buxton died in London on 12th September 1948, and was buried in the family graveyard at Upshire in Essex.

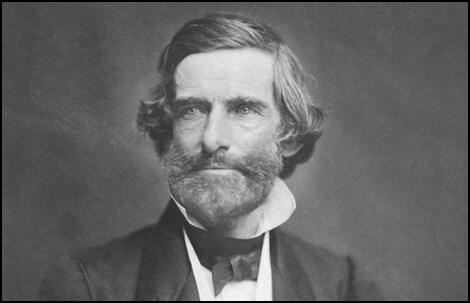

On this day in 1876 Samuel Gridley Howe, died. Samuel Gridley Howe was born in Boston on 10th November, 1801. He attended Harvard Medical School but in 1824 left for Greece to help the country in its fight for independence from Turkey. For the next three years Howe organised the medical staff of the Greek Army.

In 1831 Howe visited Paris where he studied new methods of educating the blind. He also visited Prussia where he became involved in the Polish insurrection. After being imprisoned briefly by the Prussian government he was allowed to return to the United States.

Inspired by what he had seen in Paris, in 1832 Howe established the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston. Howe soon emerged as the country's leading expert on the subject.

A strong opponent of slavery, in 1843 Howe married Julia Ward, a fellow member of the Anti-Slavery Society. Howe was also active in the Free-Soil Party and between 1851 and 1853 Howe and wife edited the anti-slavery journal, Commonwealth.

In 1865 Samuel Gridley Howe became chairman of the Massachusetts Board of State Charities and over the next nine years strenuously lobbied Congress to pass legislation to provide more aid for the education of the blind, deaf and mentally ill.

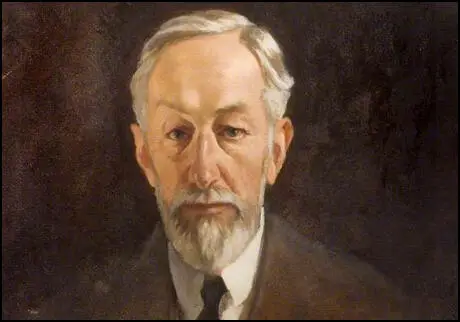

On this day in 1899 Eileen Power, was born. Eileen, the eldest of three daughters of Philip Ernest Le Poer Power (1860–1946), stockbroker, and his wife, Mabel Grindlay Clegg (1866–1903), was born at Atrincham on 9th January 1899. Her father was imprisoned for fraud in 1891, and her mother, faced with scandal and financial ruin, moved with her daughters to Bournemouth.

On the death of her mother in 1903, Eileen, Rhoda and Beryl went to live with their grandfather, Benson Clegg, in Oxford. She attended the Oxford High School for Girls. In 1907 she went to Girton College on a Clothworkers' scholarship, and took a first in both parts of the historical tripos. During her time at the University of Cambridge she joined the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. In 1910 she was awarded the Gilchrist research fellowship, and studied at the University of Paris and the École des Chartes. On her return to Britain in 1911 she was awarded the George Bernard Shaw research studentship at the London School of Economics (LSE) where she studied medieval women.

A critic of Britain's foreign policy, Power was an active member of the Union of Democratic Control during the First World War. Fellow members included Charles Trevelyan, Norman Angell, E. D. Morel, Ramsay MacDonald, J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Ottoline Morrell, Philip Morrell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Mary Sheepshanks, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville and Olive Schreiner.

Eileen Power's first book, The Paycockes of Coggeshall, was published in 1919. In 1921 she was appointed lecturer in economic history at the London School of Economics. Over the next few years she published Medieval English Nunneries (1922) and Medieval People (1924). Her biographer, Maxine L. Berg, points out that the book "went into ten editions, was the culmination of the first phase of her approach to social history. Its genesis lay in her feminist and pacifist political commitment, and in the methodology she developed of history as literature. The book was a social history deploying literary devices, but even more significantly it was a social history written to spread a message of internationalism."

Kingsley Martin was a fellow teacher at the London School of Economics. He later recalled: "Eileen Power, with whom, like everyone else, I assume was more or less in love. Eileen, indeed, was one of the most attractive women I have ever known. She was good-looking, and carried her erudition as a medieval scholar with wit and grace. She wrote delightfully, her account of the domestic life of nunneries would never bore anyone, and her Medieval People showed that careful scholarship can be made popular and achieve large sales."

Dora Russell was one of her students: "Eileen Power dealt with history. She became distinguished for her fine scholarship and her utter charm, which captivated many of both sexes. We always found it a pleasure to watch her, tall and placid and very much a personality, as she came in to take her place for dinner at high table. She had very beautiful, candid blue-grey eyes."

Eileen Power worked closely with her sister, Rhoda Power. According to Maxine L. Berg: "With her sister Rhoda she wrote children's history books, of which the most famous was Boys and Girls of History (1926). She was part of literary London, wrote widely in the press, and was a popular lecturer. During the 1920s she also started the memorable BBC schools history broadcasts which she made with Rhoda. The international aspects of medieval history, medieval trade, comparative economic history, and world history, as well as women's and social history, which Eileen Power made her own, were always made immensely attractive and immediately accessible to broad audiences by her extensive use of literary references and personal portraits."In 1927 Power helped to establish the Economic History Review.

Power published The Goodman of Paris in 1928. Three years later she became Professor of Economic History at the London School of Economics. In 1933 she joined William Beveridge in establishing the Academic Freedom Committee, an organization that helped academics fleeing from Nazi Germany. Later that year she published Studies in English Trade in the 15th Century (1933).

Power was a strong opponent of appeasement and according to Maxine L. Berg her radio broadcasts came to an end in 1936 "when she came into conflict with her producers over the political and pedagogical directions of the programmes". Power married the historian Michael Postan, who was ten years her junior, on 11th December 1937.

Eileen Power died of heart failure on 8th August 1940. Her book, The Wool Trade in English Medieval History (1941) was published posthumously. A collection of her lectures, Medieval Women, was published in 1975.

On this day in 1908 feminist author Simone de Beauvoir was born. Simone de Beauvoir, the daughter of a lawyer, was born in Paris, France on 9th January 1908. She took a degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne in 1929 and was placed second to Jean Paul Sartre, who became her close friend.

She began teaching in Marseilles in 1931 and after a spell in Rouen she moved to Paris in 1938. Along with Albert Camus and Jean Paul Sartre Beauvoir became involved in the group that published the clandestine newspaper, Combat.

In 1943 she lost her job as a teacher after being accused of corrupting of a minor. She then worked as a writer and producer for the state-run radio station. Her first novel, L'invitée (1943) brought her immediate fame. A book about her war-time experiences, The Blood of Others, was published in 1945.

Her highly acclaimed book about women, The Second Sex, appeared in 1949. She argues "one is not born but becomes a woman" With this famous phrase, Beauvoir first articulated what has come to be known as the distinction between biological sex and the social and historical construction of gender and its attendant stereotypes. Beauvoir defines women as the "second sex" because women are defined in relation to men. Beauvoir asserted that women are as capable of choice as men, and thus can choose to elevate themselves, moving beyond the "immanence " to which they were previously resigned and reaching "transcendence", a position in which one takes responsibility for oneself and the world, where one chooses one's freedom.

Other books by Beauvoir include The Mandarins (1954), The Long March (1958), Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1959), The Prime of Life (1963), Force of Circumstance (1965), A Very Easy Death (1966) and The Woman Destroyed (1970).

On this day in 1914 the United Suffragists produced a party manifesto. On 6th February 1914 a group of supporters of women's suffrage, who were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form the United Suffragists movement.

Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Henry Harben, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Mary Neal, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Barbara Ayrton Gould, Gerald Gould, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman.

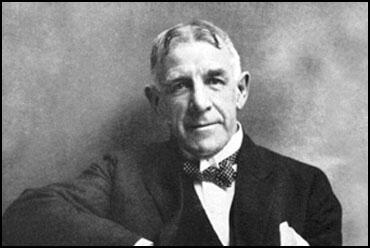

On this day in 1930 Edward Bok died in Tucson, Arizona. Bok was born in Den Helder, Holland, on 9th October, 1863. When Bok was seven years old his family emigrated to the United States. After attending school in Brooklyn, New York City, Bok found work as an office boy at the Western Union Telegraph Company.

Bok had a strong desire to become a journalist and managed to get some of his work published in the Brooklyn Eagle. He continued his education at night school and in 1887 became advertising manager of the Scribner's Magazine.

In 1889 he became editor of the Ladies' Home Journal. Bok used the magazine to campaign for women's suffrage, pacifism, conservation of the environment and improved local government. By 1900 it was the best selling magazine in the United States.

Bok retired from the Ladies' Home Journal in 1919. His autobiography, The Americanization of Edward Bok (1920) was a best-seller and won a Pulitzer Prize. He also helped to fund the $100,000 American Peace prize.

On this day day in 1957 Anthony Eden resigned as prime minister and from the House of Commons Eden claimed it was because of health issues but the real reason was the disasterous Suez Canal operation. President Dwight Eisenhower became concerned about the close relationship developing between Egypt and the Soviet Union. In July 1956 Eisenhower cancelled a promised grant of 56 million dollars towards the building of the Aswan Dam. Gamal Abdel Nasser was furious and on 26th July he announced he intended to nationalize the Suez Canal. The shareowners, the majority of whom were from Britain and France, were promised compensation. Nasser argued that the revenues from the Suez Canal would help to finance the Aswan Dam.

Eden wrote to President Dwight Eisenhower for support: "In the light of our long friendship, I will not conceal from you that the present situation causes me the deepest concern. I was grateful to you for sending Foster over and for his help. It has enabled us to reach firm and rapid conclusions and to display to Nasser and to the world the spectacle of a united front between our two countries and the French. We have however gone to the very limits of the concessions which we can make.... I have never thought Nasser a Hitler, he has no warlike people behind him. But the parallel with Mussolini is close. Neither of us can forget the lives and treasure he cost before he was finally dealt with. The removal of Nasser and the installation in Egypt of a regime less hostile to the West, must therefore also rank high among our objectives. You know us better than anyone, and so I need not tell you that our people here are neither excited nor eager to use force. They are, however, grimly determined that Nasser shall not get away with it this time because they are convinced that if he does their existence will be at his mercy. So am I."

According to Harold Wilson, a Labour Party MP, Harold Macmillan, the Foreign Secretary was the main supporter of taking action against Nasser: "Eden was at first a reluctant warrior. Macmillan was putting the heat on from the start. At a separate dinner, he and Lord Salisbury were entertaining Robert Murphy, the US Defence Secretary. Macmillan took an extremely tough line about Nasser's action, which, he later explained, was designed to stiffen the American administration. Murphy was left to draw the conclusion that Britain would certainly go to war to secure the Canal and ensure free passage for the world's ships. In the whole history of the Suez fiasco, nothing has become clearer than the effect of Macmillan's tough line with Murphy both then and throughout the following weeks, when Eden was going through the torment of preparing to use force to recapture the Canal."

At a cabinet meeting in July the minutes recorded: "The Cabinet agreed that we should be on weak ground in basing our resistance on the narrow argument that Colonel Nasser had acted illegally. The Suez Canal Company was registered as an Egyptian company under Egyptian law; and Colonel Nasser had indicated that he intended to compensate the shareholders at ruling market prices. From a narrow legal point of view, his action amounted to no more than a decision to buy out the shareholders. Our case must be presented on wider international grounds. Our argument must be that the Canal was an important international asset and facility, and that Egypt could not be allowed to exploit it for a purely internal purpose. The Egyptians had not the technical ability to manage it effectively; and their recent behaviour gave no confidence that they would recognize their international obligations in respect of it. It was a piece of Egyptian property but an international asset of the highest importance and should be managed as an international trust. The Cabinet agreed that for these reasons every effort must be made to restore effective international control over the Canal. It was evident that the Egyptians would not yield to economic pressures alone. They must be subjected to the maximum political pressure which could only be applied by the maritime and trading nations whose interests were most directly affected. And, in the last resort, this political pressure must be backed by the threat - and, if need be, the use of force."

Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the Labour Party, warned Eden of the consequences of using military force: "Lest there should be any doubt in your mind about my personal attitude, let me say that I could not regard an armed attack on Egypt by ourselves and the French as justified by anything which Nasser has done so far or as consistent with the Charter of the United Nations. Nor, in my opinion, would such an attack be justified in order to impose a system of international control over the canal – desirable though this is. If, of course, the whole matter were to be taken to the United Nations and if Egypt were to be condemned by them as aggressors, then, of course, the position would be different. And if further action which amounted to obvious aggression by Egypt were taken by Nasser, then again it would be different. So far what Nasser has done amounts to a threat, a grave threat to us and to others, which certainly cannot be ignored; but it is only a threat, not in my opinion justifying retaliation by war."

Eden feared that Nasser intended to form an Arab Alliance that would cut off oil supplies to Europe. Secret negotiations took place between Britain, France and Israel and it was agreed to make a joint attack on Egypt. On 29th October 1956, the Israeli Army invaded Egypt. Two days later British and French bombed Egyptian airfields. British and French troops landed at Port Said at the northern end of the Suez Canal on 5th November. By this time the Israelis had captured the Sinai peninsula.

According to some historians, the majority of British people were on Eden's side. On 10 and 11 November an opinion poll found 53% supported the war, with 32% opposed The majority of Conservative constituency associations passed resolutions of support of Eden. The British historian Barry Turner wrote that: "The public reaction to press comment highlighted the divisions within the country. But there was no doubt that Eden still commanded strong support from a sizeable minority, maybe even a majority, of voters who thought that it was about time that the upset Arabs should be taught a lesson. The Observer and Guardian lost readers; so too did the News Chronicle, a liberal newspaper that was soon to fold as a result of falling circulation."

Hugh Gaitskell immediately attacked the military intervention by Britain, France, and Israel, calling it "an act of disastrous folly". Gaitskell accusing Eden that he had been lying to him in private. Brian Brivati, the author of Hugh Gaitskell (1996) has pointed out that he argued that the government's policy had "compromised the three principles of bipartisan foreign policy: solidarity with the Commonwealth, the Anglo-American alliance, and adherence to the charter of the United Nations." However, it was argued: "In doing so, however, he was exposed to the Conservative charge that he had changed his position in response to the clamour of his own party's left wing. Gaitskell was in fact consistent throughout the crisis, and spoke for an internationalist tradition that was deeply rooted in British politics. It was arguably at odds with the views of some core Labour voters, but he attracted support from sections of Liberal opinion who in other respects might have found a Labour Party based on trade unions and sentiments of class solidarity unattractive."

President Dwight Eisenhower and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, grew increasingly concerned about these developments and at the United Nations the representatives from the United States and the Soviet Union demanded a cease-fire. When it was clear the rest of the world were opposed to the attack on Egypt, and on the 7th November the governments of Britain, France and Israel agreed to withdraw. According to D. R. Thorpe: "Hostile reactions from the United States, the United Nations, and the Soviet Union, then engaged in its simultaneous invasion of Hungary, led within twenty-four hours to a humiliating ceasefire. The key factor in the decision was economic. Macmillan told the cabinet on 6 November, in terms which are now known to be disingenuous in their degree of pessimism, of the run on sterling reserves (he told the cabinet of £100 million lost reserves in the first week of November, when the true figure was £31.7 million) and American treasury pressures to end the hostilities. Faced with this information, Eden had no option but to call a halt." Winston Churchill later commented on Eden's decision to invade and withdraw from Egypt: "I would never have dared, and if I had dared, I would never have dared stop".

On 20th December 1959 Anthony Eden made a statement in the House of Commons when he denied foreknowledge that Israel would attack Egypt. Robert Blake, the author British Prime Ministers in the Twentieth Century (1978) controversially argued that the it was acceptable for Eden to lie on this issue: "No one of sense will regard such falsehoods in a particularly serious light. The motive was the honourable one of averting further trouble in the Middle East, and this was a serious consideration for many years after the event."

Gamal Abdel Nasser now blocked the Suez Canal. He also used his new status to urge Arab nations to reduce oil exports to Western Europe. As a result petrol rationing had to be introduced in several countries in Europe. Eden, who had gone to stay in the home of Ian Fleming and Ann Fleming in Jamaica, came under increasing attack in the media. When Eden returned on 14th December it was to a dispirited party. On 9th January, 1957, Eden announced his resignation as Prime Minister and as a member of the House of Commons.

On this day in 1960 Vice President Richard Nixon had lunch with William Pawley, who was a close friend and business associate of Fulgencio Batista, the former dictator of Cuba. Nixon regarded Pawley as his main adviser on Latin America. During the lunch they spoke about the situation in Cuba and Nixon suggested that Pawley invited President Dwight Eisenhower for a weekend of hunting at his Virginia farm.

On 14th January, 1960, the National Security Council reviewed its policy on Cuba and Livingston T. Merchant of the State Department explained that his agency was "cooperating with CIA in action (redacted) designed to build up an opposition to Castro". The NSC members discussed different legal bases for intervention. Nixon, who had already been selected as the Republican Party candidate for the 1960 Presidential Election, urged the overthrow of Castro.

Three days later President Eisenhower had meetings to discuss proposals for covert action in Cuba. He told two NSC staffers to meet Pawley. Five days later, Pawley called one of his CIA contacts to report that Matthew Slepin, chairman of the Dade Country Republican Party, had promised twelve Cuban exiles either $20 million or $200 million on behalf of Vice President Nixon to finance the overthrow of Castro.

President Eisenhower was not in total agreement with Nixon on the plan against Castro. In a press conference held on 22nd January he claimed that the United States was continuing to prevent aggressive acts against Castro mounted from within U.S. territory, and it recognized Cuba's right to undertake domestic reforms. He also confirmed that "the policy of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other countries, including Cuba."

In July 1960, JMWAVE, the CIA station in Miami, Florida, began training a couple of hundred Cubans in counter-intelligence, in order to develop the nucleus of a post-Castro security organization in Havana. The head of the station was Ted Shackley, whose nickname was the "Blond Ghost" (because he hated to be photographed) became involved in CIA's Black Operations. Shackley was also closely associated with William Pawley and Eddie Bayo, the founder of Alpha 66.

Allen W. Dulles, the director of the CIA, put Richard Bissell, Deputy Director for Plans, in charge of this anti-Cuba task force. Later that month Dulles arranged for John F. Kennedy to meet the four leaders of the anti-Castro organization, Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front (FRD). "The purpose was to inform Kennedy of the plans that were underway to bring down the Cuban Revolution and to introduce him to the future leaders of the neighboring country."

As David Corn, the author of Blond Ghost: Ted Shackley and the CIA's Crusades (1994) has pointed out: "Agency officials... plotted fanciful schemes against Castro. The brainstorming was extreme. One imaginative CIA thinker proposed spraying Castro's broadcasting studio with a hallucinogenic chemical. The geniuses of the Technical Services Division (TSD) produced a box of cigars treated with a substance that would lead a smoker to become temporarily disoriented... In the summer of 1960, the craftsmen of TSD contaminated a box of Castro's favorite cigars with a lethal toxin. But the cigars never made it to Castro."

In September 1960, Bissell and Dulles, initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro. Robert Maheu, a private investigator and occasional CIA operative, in a conspiracy to spike Castro's food with poison. The plan was abandoned when Castro stopped visiting the Havana restaurant where he was to be poisoned.

According to an investigation carried out by Frank Church and his United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities in 1976, there were during a five year period when there was "concrete evidence of at least eight plots involving the CIA to assassinate Fidel Castro". After a newspaper report by Drew Pearson that appeared on 3rd March, 1967, about these assassination plots, President Lyndon Johnson, ordered Richard Helms, the Director of the CIA, for a detailed account of the CIA's plots to assassinate Castro. The completed report was delivered to Johnson on 10th May, 1967. Johnson later commented to a friend: "We were running a damn Murder Incorporated in the Caribbean."