On this day on 22nd January

On this day in 1561 Francis Bacon, the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon and his second wife, Anne Cooke Bacon, was born at York House in the Strand, London. His father was Lord Keeper of the Great Seal under Queen Elizabeth. His mother was the daughter of Sir Anthony Cooke, the tutor to Edward VI.

Bacon spent most of his childhood with his elder brother, Anthony Bacon, at the family home at Gorhambury House, near St Albans. His mother who was fluent in Greek and Latin as well as in Italian and French, played an important role in his education. His schooling not only included Christian teaching but also thorough training in the classics.

Anthony and Francis (who had just turned twelve) went up to Trinity College on 5th April 1573. He was described as an "academically precocious child". The brothers were put under the personal tutelage of the master, Dr John Whitgift, the future archbishop of Canterbury. According to the accounts kept by Whitgift he bought for the Bacon brothers' use the major classical texts and commentaries. These included the Iliad, Plato and Aristotle, Cicero's rhetorical works, Demosthenes' Orations... as well as the histories of Livy, Sallust, and Xenophon". Bacon later complained about his time at university as it was "barren of the production of works for the benefit of the life of man".

Bacon left Cambridge University in December 1575. The following year he joined Gray's Inn. A few months later, Francis went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador at Paris. For the next three years he visited Italy, and Spain. During his travels, Bacon studied languages and civil law while performing routine diplomatic tasks for Francis Walsingham, William Cecil and Robert Dudley.

According to his first biographer, Pierre Amboise, "Bacon spent several years of his youth in travels, to polish his wit and form his judgement, by reference to the practice of foreigners. France, Italy and Spain, being the countries of highest civilization, were those to which this curiosity drew him. As he saw himself destined to hold in his hands one day the helm of the Kingdom, he did not look only at the scenery, and the clothes of the different peoples... but took note of the different types of government, the advantages and the faults of each, and of all things the understanding of which should fit a man to govern?"

Anne Bacon was a supporter of Thomas Cartwright the Puritan preacher. As Roger Lockyer has pointed out: "Cartwright, who was only in his mid-thirties, represented a new generation of Elizabethan puritans, who took the achievements of their predecessors for granted and wished to push forward from the positions that they had established. Cartwright declared that the structure of the Church of England was contrary to that prescribed by Scripture, and that the correct model was that which Calvin had established at Geneva. Every congregation should elect its own ministers in the first instance, and control of the Church should be in the hands of a local presbytery, consisting of the minister and the elders of the congregation. The authority of archbishops and bishops had no foundation in the Bible, and was therefore unacceptable. Cartwright's definition lifted the puritan movement out of its obsession with details and threw down a challenge which the established Church could not possibly ignore."

The death of his father, Sir Nicholas Bacon, forced him to return to England. Paulet provided a letter of introduction to Queen Elizabeth that said he "would prove a very able and sufficient subject to do her Highness good and acceptable service... if God give him life". This was a reference to the fact that he was often ill during this period.

Despite Paulet's letter, he failed to find work with the Queen even though he has been described as a "genius". He wrote to his uncle William Cecil, the Lord Treasurer, asking him to petition the Queen for a government post. Apparently he refused to do this. (10) It has been claimed he did not want his son Robert Cecil, "clever, dearly loved of his father and a hunchback" to be overshadowed by the highly talented Bacon.

Francis Bacon become a lawyer. Having borrowed money, Bacon got into debt. His income being supplemented by a grant of his mother Lady Anne Bacon of the manor of Marks in Essex which generated a rent of £46. He was admitted to the bar as a barrister in June 1582. Bacon became the MP for Melcombe Regis.

In the House of Commons showed signs of sympathy to puritanism and often attended the sermons of Walter Travers. By 1584 Bacon, together with many key figures in the political nation, had become alarmed by both the perceived growing Catholic threat and the English church's suppression of the puritan clergy. Robert Lacey has commented: "A discreet homosexual, he had no intimate friends save the beautiful boys he seldom kept long, but he everywhere earned respect for his painstaking work and attention to detail."

Bacon's main enemy was his former tutor, Dr John Whitgift, who was leading an anti-puritan campaign. In a pamphlet written by Bacon. "He strongly criticized the Catholics both within and without England and gave support for the puritan cause. But his argument was couched in strongly political terms. He appealed to ‘all reason of state’ and to the example ‘of the most wise, most politic, and best governed estates’. For the danger within the queen should do everything possible to strengthen protestantism, mainly through promoting preaching and schooling, because all her ‘force and strength and power’ consisted in her protestant subjects."

Francis Bacon suggested to Queen Elizabeth should follow a policy of religious toleration. Philippa Jones has argued: "Francis wrote a lengthy report on the situation to the Queen, suggesting that more might be achieved if penalties against Catholics were relaxed, thus removing some of the cause of their discontent and the temptation to join in with any treasonable plots."

Francis Bacon was employed by England's spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham to investigate English Catholics. In the parliament which met in winter 1586–7 Bacon argued for the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, and was named to the committee appointed to draw up a petition for her execution. In August 1588 Bacon was appointed to a government committee examining recusants in prison and a few months later, in December 1588, he was appointed to a committee of lawyers which was to review existing statutes.

Bacon became close to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex in 1592. He was one of Queen Elizabeth's most important advisers and since the death of Walsingham had taken command of the intelligence service. Essex was impressed with Bacon and decided to recruit him and his brother, Anthony Bacon. Essex's biographer, Robert Lacey, has pointed out: "In the spring of 1592 Essex and the Bacon brothers found themselves outside the citadel of real political power: but possessing between them the intelligence, the industry, the contacts, the wealth and the pedigree they needed to force an entry. The story of the next six years is the story of how between them they did just that and carved out for themselves a position of potentially overwhelming might."

The men joined forces in developing the case against Roderigo Lopez, the personal physician to Queen Elizabeth. As Anna Whitelock has pointed out: "As the Queen's physician, Lopez had a dual task: the preservation of the body of the Queen in her Bedchamber. Elizabeth liked and trusted him and granted him a valuable perquisite: a monopoly for importing aniseed and other herbs essential to the London apothecaries."

Essex asked Thomas Phelippes to investigate Lopez. He discovered a secret correspondence between Estevão Ferreira da Gama, and the count of Fuentes, in the Spanish Netherlands. This was followed by the arrest of Lopez's courier, Gomez d'Avila. When he was interrogated he implicated Lopez. Phelippes also discovered a letter that stated: "The King of Spain had gotten three Portuguese to kill her Majesty and three more to kill the King of France".

On 28th January 1594, Essex, wrote a letter to Anthony Bacon: "I have discovered a most dangerous and desperate treason. The point of conspiracy was her Majesty's death. The executioner should have been Doctor Lopez. The manner by poison. This I have so followed that I will make it appear as clear as the noon day."

Essex employed Francis Bacon to write up the evidence against Roderigo Lopez and this was used against him at his trial. Sir Edward Coke, the Attorney-General, opened the trial by arguing that Lopez and his associates had been seduced by Jesuit priests with great rewards to kill the Queen "being persuaded that it is glorious and meritorious, and that if they die in the action, they will inherit heaven and be canonised as saints". He pointed out that Lopez was "her Majesty's sworn servant, graced and advanced with many princely favours, used in special places of credit, permitted often access to her person, and so not suspected... This Lopez, a perjuring murdering traitor and Jewish doctor, more than Judas himself, undertook the poisoning, which was a plot more wicked, dangerous and detestable than all the former."

Coke emphasized the three men's secret Judaism and they were all convicted of high treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. However, the Queen remained doubtful of her doctor's guilt and delayed giving the approval needed to carry out the death sentences. William Cecil wanted to ensure that Lopez was executed to protect himself from a possible investigation. "From Cecil's point of view Lopez knew too much and therefore had to be silenced". Roderigo Lopez, Manuel Luis Tinoco, and Estevão Ferreira da Gama were executed at Tyburn on 7th June 1594.

Essex proposed to Queen Elizabeth that Francis Bacon should become her attorney-general. However, his behaviour in the House of Commons showed that he would not automatically support government policies. Bacon opposed extra taxes needed to carry out future military action. He argued that this proposed new tax would cause economic problems for his constituents: "The gentlemen must sell their plate and the farmers their brass pots were this will be paid. And as for us, we are here to search the wounds of the realm and not to skin them over".

Bacon proposed that the collection of this tax should be spread over six instead of four years. This brought Bacon into conflict with Robert Cecil and other ministers of the crown. When in the course of the next few months, Bacon attempted to secure for himself "a government office of prominence and profit" he was "sharply rebuffed". As Robert Lacey, the author of Robert, Earl of Essex (1971) has pointed out: "The speech that had been intended simply to discomfort the Cecils had discomforted the Queen as well."

Queen Elizabeth told William Cecil that she thought that Bacon was "in more fault than any of the rest in Parliament". As soon as Cecil had informed him of the queen's anger Bacon tried to excuse his speech. "The manner of my speech", he told his uncle, "did most evidently show that I spake simply and only to satisfy my conscience, and not with any advantage or policy to sway the cause". In expressing his sincere opinions Bacon had simply endeavoured to signify his "duty and zeal towards her Majesty and her service".

Realizing that he had miscalculated the impact his speeches would have on the Queen and he told Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, that he would "retire myself with a couple of men to Cambridge, and there spend my life in my studies and contemplations, without looking back". No such retirement took place. In July 1594 the queen made Bacon one of her learned counsel and he was employed in several legal cases.

In January 1597 Francis Bacon published Essays. It has been claimed that it was "the most revolutionary little book to leave the English printing press until then... Bacon's Essays were consummate art, significant not simply in their own right but in the context of English prose was born with their publication." Henry Hallam, the author of Introduction to the Literature of Europe in the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Seventeenth Centuries (1854) agrees and wrote that "They are deeper and more discriminating than any earlier, or almost any later, work in the English language".

Bacon tackled a variety of different subjects. This included highly controversial issues such as religion and democracy: "A monarchy, where there is no nobility at all, is ever a pure and absolute tyranny; as that of the Turks. For nobility attempters sovereignty, and draws the eyes of the people, somewhat aside from the line royal. But for democracies, they need it not; and they are commonly more quiet, and less subject to sedition, than where there are stirps of nobles.... It is well, when nobles are not too great for sovereignty nor for justice; and yet maintained in that height, as the insolency of inferiors may be broken upon them, before it come on too fast upon the majesty of kings. A numerous nobility causeth poverty, and inconvenience in a state; for it is a surcharge of expense; and besides, it being of necessity, that many of the nobility fall, in time, to be weak in fortune, it maketh a kind of disproportion, between honor and means."

Francis Bacon also dealt with more personal issues such as friendship and parenthood: "The joys of parents are secret; and so are their griefs and fears. They cannot utter the one; nor they will not utter the other. Children sweeten labors; but they make misfortunes more bitter. They increase the cares of life; but they mitigate the remembrance of death. The perpetuity by generation is common to beasts; but memory, merit, and noble works, are proper to men. And surely a man shall see the noblest works and foundations have proceeded from childless men; which have sought to express the images of their minds, where those of their bodies have failed. So the care of posterity is most in them, that have no posterity. They that are the first raisers of their houses, are most indulgent towards their children; beholding them as the continuance, not only of their kind, but of their work; and so both children and creatures."

In this essay Francis Bacon revealed his own feelings about being the youngest child and a secret homosexual. "The difference in affection, of parents towards their several children, is many times unequal; and sometimes unworthy; especially in the mothers; as Solomon saith, A wise son rejoiceth the father, but an ungracious son shames the mother. A man shall see, where there is a house full of children, one or two of the eldest respected, and the youngest made wantons; but in the midst, some that are as it were forgotten, who many times, nevertheless, prove the best. The illiberality of parents, in allowance towards their children, is an harmful error; makes them base; acquaints them with shifts; makes them sort with mean company; and makes them surfeit more when they come to plenty. And therefore the proof is best, when men keep their authority towards the children, but not their purse. Men have a foolish manner (both parents and schoolmasters and servants) in creating and breeding an emulation between brothers, during childhood, which many times sorteth to discord when they are men, and disturbeth families."

Following his successful raid on the Spanish navy in Cadiz, Bacon's patron, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, had a flaming disagreement with Queen Elizabeth. She was furious with Essex for giving the booty from Cadiz to his men. She ordered William Cecil to carry out an investigation into Essex's conduct of the campaign. He was eventually cleared of incompetence but it has been claimed that Elizabeth never forgave him for his actions. Essex had hoped to be appointed to the prestigious and lucrative post of master of the Court of Wards. According to Roger Lockyer the Queen refused to give him what he wanted because she "distrusted his popularity and also resented the imperious manner in which he claimed advancement.

In February 1597 Francis Bacon decided that Essex was a dangerous man to be associated with and wrote to William Cecil apologizing for work he had carried out in the past on Essex's behalf that might have been opposed to those of Cecil's: "In like humble manner I pray your Lordship to pardon mine errors, and not to impute unto me the errors of any other... but to conceive of me to be a man that daily profiteth in duty."

This was a sensible move because on 7th February, 1601, Essex was visited by a delegation from the Privy Council and was accused of holding unlawful assemblies and fortifying his house. Fearing arrest and execution he placed the delegation under armed guard in his library and the following day set off with a group of two hundred well-armed friends and followers, entered the city. Essex urged the people of London to join with him against the forces that threatened the Queen and the country. This included Robert Cecil and Walter Raleigh. He claimed that his enemies were going to murder him and the "crown of England" was going to be sold to Spain.

At Ludgate Hill his band of men, that included his step-father, Sir Christopher Blount, were met by a company of soldiers. As his followers scattered, several men were killed and Blount was seriously wounded. Essex and about 50 men managed to escape but when he tried to return to Essex House he found it surrounded by the Queen's soldiers. Essex surrendered and was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

On 19th February, 1601, Essex and some of his men were tried at Westminster Hall. He was accused of plotting to deprive the Queen of her crown and life as well as inciting Londoners to rebel. Essex protested that "he never wished harm to his sovereign". The coup, he claimed was merely intended to secure access for Essex to the Queen". He believed that if he was able to gain an audience with Elizabeth, and she heard his grievances, he would be restored to her favour. Essex was found guilty of treason and was executed on 25th February.

In the last Elizabethan parliament, which met in October 1601, Bacon sat for Ipswich. He supported the subsidy bill of four subsidies and emphasized that the poor as well as the rich should contribute. This brought him into conflict with Walter Raleigh. Bacon also insisted that parliament, as well as raising money, must enact laws. He brought in a bill "against abuses in weights and measures" and spoke "for repealing superfluous laws’.

Bacon and Raleigh also argued against each other in a debate about the renewal of the Statute of Tillage. Bacon defended the bill, which enacted that land converted to pasture should be restored to tillage, noting that "the husbandman", being "a strong and hardy man", made the best soldier. Raleigh replied that since "all Nations abound with Corn" it was best "to set it at Liberty, and leave every man Free, which is the Desire of a true Englishman". Bacon's view, receiving support from his cousin Robert Cecil, prevailed.

Queen Elizabeth died on 24th March, 1603. The succession of James I brought Bacon into greater favour. He was knighted in 1603. The following year, Bacon married Alice Barnham, the he 14-year-old daughter of a well-connected London merchant Benedict Barnham. According to Robert Lacey "it was not until the reign of James that he achieved the eminence for which he had always been prepared to sacrifice so much self respect".

In 1603 Bacon also published a short treatise on the proposed union between England and Scotland entitled A Brief Discourse Touching the Happy Union of the Kingdoms of England and Scotland. This was a work of propaganda on behalf of the king. Privately, Bacon had his doubts, thinking that the king "hastened to a mixture of both kingdoms and nations, faster perhaps than policy will conveniently bear" but on the whole he fully supported the union. He wrote about the importance of uniting "these two mighty and warlike nations of England and Scotland into one kingdom".

In October 1605 he published his first philosophical book, The Advancement of Learning. The work was a general survey of the contemporary state of human knowledge, identifying its deficiencies and supplying Bacon's broad suggestions for improvement. Roger Lockyer, the author of Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985) has argued that Bacon was the first major English figure in the scientific revolution. "Francis Bacon... made himself the propagandist of the scientific method and constantly urged the need for experiment and research. The high position that he held and the fame of his name formed a shelter behind which enquiring men could pursue their researches, and the freedom given to scientific speculation in England may account for the fact that by the late seventeenth century London had become the capital of the scientific as well as the commercial world. It was Bacon's hope that academies would be formed where scientists could exchange information, for he recognised the paramount importance of communications to the spread of knowledge."

Francis Bacon held the important posts of Solicitor General (1607), Attorney General (1613) and Lord Chancellor (1618). In 1620 he published Novum Organum Scientiarum (New Instrument of Science). In the book he argued: "The sciences which we possess come for the most part from the Greeks. But from all these systems of the Greeks, and their ramifications through particular sciences, there can hardly after the lapse of so many years be adduced a single experiment which tends to relieve and benefit the condition of man."

Matthew Syed believes that this was "a truly devastating assessment" as he was suggesting that since the Greeks scientific progress had not been taking place. "The teachings of the early church were brought together with the philosophy of Aristotle (who had been elevated to a revered authority) to create a new, sacrosanct worldview. Anything that contradicted Christian teaching was considered blasphermous. Dissenters were published."

In 1621 he was impeached by Parliament for bribery and corruption. Not since the fifteenth century had a great officer of the crown been overthrown in Parliament. Bacon expected to be protected by James I but he told the "Lords that while they should proceed with all due care they should not scruple to pass judgment where they found good cause". When he heard this was the view of the king he acknowledged his guilt.

Bacon was fined £40,000 and "imprisonment at the king's pleasure". He was also barred from any office or employment in the state and forbidden to sit in parliament or come within the verge (12 miles) of the court. The fine was never collected and his imprisonment in the Tower of London lasted only three days. Francis Bacon died aged 65, on 9th April 1626.

On this day in 1788 George Gordon, the son of Captain John Byron and Catherine Gordon, was born in London. Born with a club-foot, he spent the first ten years in his mother's lodgings in Aberdeen. Although originally a rich women, her fortune had been squandered by her husband.

In 1798 George succeeded to the title, Baron Byron of Rochdale, on the death of his great-uncle. Money was now available to provide Lord Byron with an education at Harrow School and Trinty College, Cambridge.

Lord Byron's first collection of poems, Hours of Idleness, appeared in 1807. The poems were savagely attacked by Henry Brougham in the Edinburgh Review. Byron replied with the publication of his satire, English Bards and Scotch Reviewers (1809).

In 1809 Byron set on his grand tour where he visited Spain, Malta, Albania and Greece. His poetical account of this grand tour, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812) established Byron as one of England's leading poets.

Lord Byron scandalized London by starting an affair with Lady Caroline Lamb and was ostracized when he was suspected of having a sexual relationship with his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, who gave birth to an illegitimate daughter.

Byron attending the House of Lords where he became a strong advocate of social reform. In 1811 he was one of the few men in Parliament to defend the actions of the Luddites and the following year spoke against the Frame Breaking Bill, by which the government intended to apply the death-penalty to Luddites. Byron's political views influenced the subject matter of his poems. Important examples include Song for the Luddites (1816) and The Landlords' Interest (1823). Byron also attacked his political opponents such as the Duke of Wellington and Lord Castlereagh in Wellington: The Best of the Cut-Throats (1819) and the The Intellectual Eunuch Castlereagh (1818).

Annabella Milbanke rejected his first marriage proposal but accepted his second proposal in 1814 and they were married on 2nd January 1815. Their daughter, Ada, was born in December of that year. However Byron's continuing obsession with Augusta and his continuing sexual escapades with actresses and others, made their marital life difficult. Annabella considered Lord Byron insane, and in January 1816 she left him, taking their daughter, and began proceedings for a legal separation. A few months later he labeled his former wife a "moral Clytemnestra."

Byron moved to Venice where he met the Countess Teresa Guiccioli, who became his mistress. Some of Byron's best known work belongs to this period including Don Juan. The last cantos is a satirical description of social conditions in England and includes attacks on leading Tory politicians.

Lord Byron also began contributing to the radical journal, the Examiner, edited by his friend, Leigh Hunt. Leigh Hunt, like other radical journalists had suffered as as result of the Gagging Acts and had been imprisoned for his attacks on the monarchy and the government.

In 1822 Byron, Leigh Hunt, and Percy Bysshe Shelley travelled to Italy where the three men published the political journal, The Liberal. By publishing in Italy they remained free from the fear of being prosecuted by the British authorities. The first edition was mainly written by Leigh Hunt but also included work by William Hazlitt, Mary Shelley and Byron's Vision of Judgement sold 4,000 copies. Three more editions were published but after the death of Shelley in August, 1822, the Liberal came to an end.

For a long time Lord Byron had supported attempts by the Greek people to free themselves from Turkish rule. This included writing poems such as The Maid of Athens (1810). In 1823 he formed the Byron Brigade and joined the Greek insurgents who had risen against the Turks. However, in April, 1824, Lord Byron died of marsh fever in Missolonghi before he saw anymilitary action.

On this day in 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in America to receive a medical degree. Elizabeth Blackwell was born in Bristol, England, on 3rd February, 1821. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, held progressive views and Elizabeth and her sisters were taught subjects such as Latin, Greek and mathematics.

In 1832 the Blackwell family emigrated to the United States. Samuel Blackwell was strongly opposed to slavery and after meeting William Lloyd Garrison, became involved in Abolitionist activities. When her husband died in 1838 Hannah Blackwell had nine children to look after. Elizabeth contributed to the family income by opening a small private school with two of her sisters, Anna and Marian, in Cincinnati. Later she taught in Kentucky and North Carolina.

Elizabeth became interested in the topic of medicine. At that time there were no women doctors in the United States but Elizabeth argued that many women would prefer to consult with a woman rather than a man about her health problems. She was rejected by 29 medical schools before being accepted by Geneva Medical School in 1847. The male students ostracized her and teachers refused permission for her to attend medical demonstrations. Despite these problems, when graduated in 1849 she was ranked first in her class. She also became the first woman to qualify as a doctor in the United States and over 20,000 people turned up to watch Blackwell being awarded her MD.

Elizabeth now moved to Europe where she took a midwives' course at La Maternite in Paris. While in France she contracted purulent ophthalma from a baby she was treating. As a result of this infection she lost the sight of one eye. Elizabeth now had to abandon her plans to become a surgeon.

In October, 1850, Elizabeth moved to England where she worked under Dr. James Paget at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London. It was here that she met and became friends with Florence Nightingale and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Both these women were inspired by Elizabeth's success and became pioneers in women's medicine in Britain.

Elizabeth Blackwell returned to the United States in 1851 and attempted to find work in New York. Refused posts in the city's hospitals and dispensaries, she was forced to work privately. Her experiences of gender discrimination encouraged her to write the book The Laws of Life (1852).

In 1853 Elizabeth opened a dispensary in the slums of New York. Soon afterwards she was joined by her younger sister, Emily Blackwell, who had now also graduated with a medical degree, and Marie Zakrzewska. In 1857 the three women established the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The women gave public lectures on hygiene, created a health centre, appointed sanitary visitors and campaigned for better preventive medicine

During the American Civil War Elizabeth organized the Women's Central Association of Relief. This involved the selection and training of nurses for service in the war. Blackwell, along with Emily Blackwell and Mary Livermore, played an important role in the development of the United States Sanitary Commission.

After the war the Blackwell sisters established the Women's Medical College in New York. Elizabeth became professor of hygiene until 1869 when he moved to London to help form the National Health Society and the London School of Medicine for Women. After meeting Charles Kingsley Blackwell became active in the Christian Socialist movement.

In 1875 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson invited Blackwell to became professor of gynecology at the London School of Medicine for Children. She remained in this post until she had a serious fall in 1907.

Elizabeth Blackwell died in Hastings, Sussex, on 31st May, 1910.

On this day in 1859 Henry Hyde Champion, the son of Major-General J. H. Champion, was born in India on 22nd January, 1859. He attended Marlborough College and after achieving a military commission in the Royal Artillery served with distinction in the Second Afghan War.

In 1881 he returned to England after becoming ill with typhoid. While recovering in PortsmouthHenry Champion read a great deal, including Progress and Poverty by Henry George, the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and several books by John Stuart Mill. These books radicalized Champion and he began to question Britain's foreign policy. In 1882 Champion resigned from the British Army in protest at its Egyptian campaign.

Henry Champion now described himself as a Christian Socialist and in 1882 became editor of the journal, the Christian Socialist. He also joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and showed his commitment by giving the party £2,000. H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the SDF, appointed Champion as editor of the organisation's newspaper, Justice.

In the 1885 General Election, Champion and Hyndman, without consulting their colleagues, accepted £340 from the Conservative Party to run parliamentary candidates in Hampstead and Kensington. The objective being to split the Liberal vote and therefore enabling the Conservative candidate to win. This strategy did not work and the two SDF's candidates only won 59 votes between them. The story leaked out and the political reputation of both men suffered from the idea that they were willing to accept "Tory Gold".

Tom Mann got to know Champion during this period: "Henry Hyde Champion was about my own age, an ex-artillery officer, a foremost member of the SDF, taking part in all forms of propagandist activity, showing keen sympathy with the unemployed. He had a fine, earnest face, and a serious manner in dealing with the sufferings of the workers. Champion, being a man of vigorous individuality, and genuinely devoted to the movement, could not always wait to get his views as to various forms of propagandist activity endorsed by a committee. He would act upon his own initiative, and commit the organization to plans and projects without consultation. Naturally this would give rise to strong expressions of opinion, frequently of an adverse character, arising from the natural human dislike to being pitch-forked into a project, however excellent, without having any reasonable opportunity for consideration."

In 1886 the Social Democratic Federation became involved in organizing strikes and demonstrations against low wages and unemployment. After one demonstration that led to a riot in London, Champion, H. M. Hyndman and John Burns, were arrested but at their subsequent trial they were all acquitted.

Champion, a Christian Socialist, objected to Hyndman's atheism. He was also concerned by Hyndman's support of violent revolution. Champion's criticisms of Hyndman resulted in him being expelled from the SDF in 1887. He joined the Fabian Society, and although he respected the ideas of George Bernard Shaw and Annie Besant, he was disappointing by their lack of interest in forming a working-class political party.

In 1888 Champion, John Burns and Tom Mann formed the Labour Elector. Edited by Champion, the paper campaigned for the eight-hour day, denounced bad employers and criticised trade union Liberal MPs in the House of Commons. The Labour Elector argued strongly for a new working-class party with strong links to the trade union movement.

As well as writing about industrial disputes, Champion also helped to organize them, and in 1888 joined with Annie Besant and her socialist journal, The Link, to help the Matchgirls Union defeat the Bryant & May company. The following year Champion emerged with Ben Tillett, Tom Mann and John Burns as one of the leaders of the London Dock Strike. Tillett later recalled: "Our principal Press Officer (during the 1889 Dock Strike) was the socialist journalist, Henry Hyde Champion, one of the founders of the Fabian Society. Although he was in no way officially connected with the strike, he rendered us very valuable help."

Champion had argued for a long time that the British working-class needed a political party that would provide an alternative to the Social Democratic Federation. He therefore fully supported the formation of the Independent Labour Party in 1894. However, trade unionists in the organisation were suspicious of Champion because of his privileged background.

At a conference in Manchester in February 1894, references were made to Champion's involvement with the Conservative Party in the 1884 General Election and delegates suggested that he was not to be trusted. The Times reflected the views of many members: "Champion was an exceedingly able writer and the wielder of a caustic pen. He had, however, the temperament of an aristocrat and an inborn sympathy with Conservative traditions, both of which prevented him from really understanding and sympathizing with the minds of the masses whom he endeavoured to lead."

Henry Hyde Champion was so upset by the comments at the conference that he left the Independent Labour Party and emigrated to Australia. Champion settled in Melbourne where he married Elsie Belle Goldstein, the younger sister of the Australian suffragist Vida Goldstein.

Champion suffered a stroke in 1901 which left him semi-paralysed, with his speech affected and a limp, and unable ever again to use his right hand for typing. However, in 1906 he was able to establish the Australasian Authors' Agency, that published the work of aspiring Australian novelists.

Champion became friends with David Low during the First World War. He later recorded: "Who in 1915 would have identified the mild old gentleman, editor of a tiny literary monthly, walking tremulously with the aid of two sticks in the Melbourne sunshine, with the determined young ex-artillery officer H. H. Champion of the 1880s... No one, I wager. Illness, disappointment and age had long since withdrawn Champion from politics to books. But he retained an interest in justice and right."

Henry Hyde Champion died in South Yarra on 30th April 1928.

On this day in 1876 Flora Sandes, the daughter of Samuel Sandes, a Scottish clergyman, was born. On the outbreak of the First World War, Sandes joined an ambulance unit in Serbia on the Eastern Front.

In November, 1915, the Serbian Army was unable to stop Austro-German and Bulgarian forces advancing deep into Serbia. Sandes joined the army when it retreated into Kosovo and by the end of November, the forces had reached the Albanian mountains.

Although nearly forty years old, in December 1916, was promoted to the rank of sergeant-major. In an effort to raise funds for the Serbian forces, Sandes wrote and published, An English Woman-Sergeant in the Serbian Army (1916).

After the war, Sandes remained in the Serbian Army and had reached the rank of major by the time she retired. In 1927 Sandes married the former White Army general, Yurie Yudenich. After her husband's death in September, 1941, Sandes returned to England. Flora Sandes died at her Suffolk home on 24th November 1956.

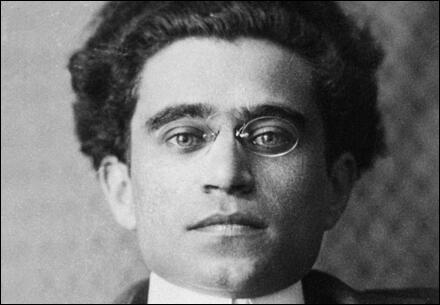

On this day in 1891 Antonio Gramsci was born in Ales, Sardina. Although born into poverty he was extremely intelligent and in 1911 won a scholarship to Turin University. While a student in Italy Gramsci became involved in politics. He joined the Italian Socialist Party in 1914 and inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution he took an active part in the workers' occupation of factories in 1918.

Gramsci was disillusioned by the unwillingness of the Italian Socialist Party to advocate revolutionary struggle. Encouraged by Vladimir Lenin and the Comintern, Gramsci joined with Palmiro Togliatti to form the Italian Communist Party in 1921.

Gramsci visited the Soviet Union in 1922 and two years later became leader of the communists in parliament. An outspoken critic of Benito Mussolini and his fascist government, he was arrested and imprisoned in 1928.

While in prison Gramsci wrote a huge collection of essays which later established his reputation as one of the most important radical theorists since Karl Marx. In his essays he criticized those who had turned Marxism into a closed system, with immutable laws. He argued that the collapse of capitalism and its replacement with socialism was not inevitable and rejected Lenin's belief that revolution could be brought about by a small, dedicated minority. While this worked in a backward country such as Russia in 1917 he doubted it would be successful in more advanced countries in Europe.

In his writings Gramsci emphasized the importance of the way the ruling class controlled institutions such as the press, radio and trade unions. Gramsci believed that the only way the power of the state could be overthrown was when the majority of the workers desired revolution.

Antonio Gramsci died in prison in 1937. His book, Prison Notebooks, was published in 1947 and his theories, that advocated persuasion, consent and doctrinal flexibility, had a major influence on left-wing radicals in post-war Europe.

On this day in 1901 Queen Victoria died. Alexandrina Victoria, the only child of Edward, Duke of Kent and Victoria Maria Louisa of Saxe-Coburg, was born in 24th May 1819. The Duke of Kent was the fourth son of George III and Victoria Maria Louisa was the sister of King Leopold of Belgium. The Duke and Duchess of Kent selected the name Victoria but her uncle, George IV, insisted that she be named Alexandrina after her godfather, Tsar Alexander II of Russia.

Victoria's father died when she was eight months old. The Duchess of Kent developed a close relationship with Sir John Conroy, an ambitious Irish officer. Conroy acted as if Victoria was his daughter and had a major influence over her as a child.

On the death of George IV in 1830, his brother William IV became king. William had no surviving legitimate children and soVictoria, became his heir. William's health was not good and he feared that Conroy would become the power behind the throne if Victoria became queen before she was eighteen.

William IV died 27 days after Victoria's eighteenth birthday. Although William was unaware of this, Victoria disliked Conroy and she had objected to his attempt to exert power over her. As soon as she became queen in 1837, Victoria banished Conroy from the Royal Court.

Lord Melbourne was Prime Minister when Victoria became queen. Melbourne was fifty-eight and a widower. Melbourne's only child had died and he treated Victoria like his daughter. Queen Victoria grew very fond of Melbourne and became very dependent on him for political advice. Melbourne was leader of the Whig party and although radical in his youth, his views were now extremely conservative. Melbourne had been a member of Earl Grey's government that had passed the 1832 Reform Act, but he had privately been against the measure. Melbourne attempted to protect Victoria from the harsh realities of British life and even advised her not to read Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens because it dealt with "paupers, criminals and other unpleasant subjects".

Queen Victoria and Melbourne became very close. An apartment was made available for Lord Melbourne at Windsor Castle and it was estimated that he spent six hours a day with the queen. Victoria's feelings for Melbourne were clearly expressed in her journal. On one occasion she wrote: "he is such an honest, good kind-hearted man and is my friend, I know it."

Some people objected to this close relationship. When on royal visits, some members of the crowd would shout out "Mrs. Melbourne". Lord Melbourne's old friend, Thomas Barnes, the editor of The Times wrote "Is it for the Queen's service - is it for the Queen's dignity - is it becoming - is it commonly decent?" In the autumn of 1837 a rumour circulated that Victoria was considering marrying Lord Melbourne. Queen Victoria wrote in her diary that she was growing very fond of Melbourne and loved listening to him talk: "Such stories of knowledge; such a wonderful memory; he knows about everybody and everything; who they were and what they did. He has such a kind and agreeable manner; he does me the world of good."

In 1839 Lord Melbourne resigned after a defeat in the House of Commons. Sir Robert Peel, the Tory leader, now became Prime Minister. It was the custom for the Queen's ladies of the bedchamber to be of the same political party as the government. Peel asked Victoria to replace the Whig ladies with Tory ladies. When Victoria refused, Peel resigned and Melbourne and the Whigs returned to office.

Soon after the return of Lord Melbourne as Prime Minister, Victoria saw Lady Flora Hastings, one of her ladies-in-waiting, getting into a carriage with Sir John Conroy. A few months later Victoria noticed that Lady Hastings appeared to be pregnant. When Victoria approached Lady Hastings about this she claimed that she was still a virgin and had not had a sexual relationship with Conroy. Victoria refused to believe her and insisted that she submitted to a medical examination. The queen's doctor discovered that Lady Hastings was indeed a virgin and that the swelling was caused by a cancerous growth on the liver. The story was leaked to the newspapers and when Lady Hastings died of cancer a few months later, Victoria became very unpopular with the British public. Soon afterwards an attempt was made to kill Victoria while she was driving in her carriage in London. Further assassination attempts took place in 1842 (twice), 1849, 1850, 1872 and 1882.

Queen Victoria's cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg, visited London in 1839. Victoria immediately fell in love with Albert and although he initially had doubts about the relationship, the couple were eventually married in February 1840. During the next eighteen years Queen Victoria gave birth to nine children.

Lord Melbourne resigned as Prime Minister in 1841. However, by this time, it was Prince Albert, rather than Melbourne, who had become the main influence over Victoria's political views. Whereas Melbourne had advised Victoria not to think about social problems, Prince Albert invited Lord Ashley to Buckingham Palace to talk about what he had discovered about child labour in Britain.

Queen Victoria had a good relationship with the next two prime ministers, Sir Robert Peel and Lord John Russell. However, she disapproved of Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary. Palmerston believed the main objective of the government's foreign policy should be to increase Britain's power in the world. This sometimes involved adopting policies that embarrassed and weakened foreign governments. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, on the other hand, believed that the British government should do what it could to help preserve European royal families against revolutionary groups advocating republicanism. This was very important to Victoria and Albert as they were closely related to several of the European royal families that faced the danger of being overthrown.

Victoria and Albert also objected to Palmerston's sexual behaviour. On one occasion he had attempted to seduce one of Victoria's ladies in waiting. Palmerston entered Lady Dacre's bedroom while staying as Queen Victoria's guest at Windsor Castle. Only Lord Melbourne's intervention saved Palmerston from being removed from office.

In the summer of 1850 Queen Victoria asked Lord John Russell to dismiss Palmerston. Russell told the queen he was unable to do this because Palmerston was very popular in the House of Commons. However, in December 1851, Lord Palmerston congratulated Louis Napoleon Bonaparte on his coup in France. This action upset Russell and other radical members of the Whig party and this time he accepted Victoria's advice and sacked Palmerston. Six weeks later Palmerston took revenge by helping to bring down Lord John Russell's government.

In 1855 Lord Palmerston became Prime Minister. Queen Victoria found it difficult to work with him but their relationship gradually improved. When Palmerston died she wrote in her journal: "We had, God knows! terrible trouble with him about Foreign Affairs. Still, as Prime Minister he managed affairs at home well, and behaved to me well. But I never liked him."

Prince Albert died of typhoid fever in December 1861. Victoria continued to carry out her constitutional duties such as reading all diplomatic despatches. However, she completely withdrew from public view and now spent most of her time in the Scottish Highlands at her home at Balmoral Castle. Victoria even refused requests from her government to open Parliament in person. Politicians began to question whether Victoria was earning the money that the State paid her.

While at Balmoral Queen Victoria became very close to John Brown, a Scottish servant. Victoria's friendship with Brown caused some concern and rumours began to circulate that the two had secretly married. Hostility towards Victoria increased and some Radical MPs even spoke in favour of abolishing the British monarchy and replacing it with a republic.

In 1868 William Gladstone, leader of the Liberals in the House of Commons, became Prime Minister. Gladstone's government had plans for a series of reforms including the extension of the franchise, elections by secret ballot and a reduction in the power of the House of Lords. Victoria totally disagreed with these policies but did not have the power to stop Gladstone's government from passing the 1872 Secret Ballot Act.

In 1874 the Tory, Benjamin Disraeli, became Prime Minister. Victoria much preferred Disraeli's conservatism to Gladstone's liberalism. Victoria also approved of Disraeli's charm. Disraeli later remarked that: "Everyone likes flattery, and when you come to royalty, you should lay it on with a trowel." Queen Victoria was very upset when Gladstone replaced Disraeli as premier in 1880. When Disraeli died the following year, Victoria wrote to his private secretary that she was devastated by the news and could not stop crying.

Gladstone's relationship with Victoria failed to improve. As well as her objection to the 1884 Reform Act, Victoria disagreed with Gladstone's foreign policy. William Gladstone believed that Britain should never support a cause that was morally wrong. Victoria took the view that not to pursue Britain's best interest was not only misguided, but close to treachery. In 1885 Victoria sent a telegram to Gladstone criticizing his failure to take action to save General Gordon at Khartoum. Gladstone was furious because the telegram was uncoded and delivered by a local station-master. As a result of this telegram it became public knowledge that Victoria disapproved of Gladstone's foreign policy. The relationship became even more strained when Gladstone discovered that Victoria was passing on confidential documents to the Marquess of Salisbury, the leader of the Conservatives.

In 1885 the Marquess of Salisbury became Prime Minister. He was to remain in power for twelve of the last fifteen years of her reign. Victoria shared Salisbury's imperialist views and was thrilled when General Kitchener was successful in avenging General Gordon in the Sudan in 1898. Victoria also enthusiastically supported British action against the Boers in South Africa.

On this day in 1924 Ramsay MacDonald becomes the first Labour Prime Minister of Britain. .In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. David Marquand has pointed out that: "The new parliamentary Labour Party was a very different body from the old one. In 1918, 48 Labour M.P.s had been sponsored by trade unions, and only three by the ILP. Now about 100 members belonged to the ILP, while 32 had actually been sponsored by it, as against 85 who had been sponsored by trade unions.... In Parliament, it could present itself for the first time as the movement of opinion rather than of class."

Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". The Daily Mail warned about the dangers of a Labour government and the Daily Herald commented on the "Rothermere press as a frantic attempt to induce Mr Asquith to combine with the Tories to prevent a Labour Government assuming office". John R. Clynes, the former leader of the Labour Party, argued: "Our enemies are not afraid we shall fail in relation to them. They are afraid that we shall succeed."

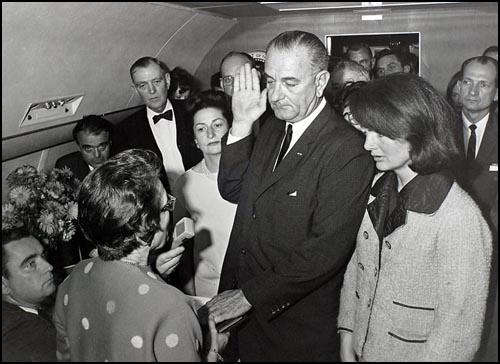

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it.

Robert Smillie, the Labour MP for Morpeth, believed that MacDonald had made a serious mistake in forming a government. "At last we had a Labour Government! I have to tell you that I did not share in that jubilation. In fact, had I had a voice in the matter which, as a mere back-bencher I did not, I would have strongly advised MacDonald not to touch the seals of office with the proverbial bargepole. Indeed, I was very doubtful indeed about the wisdom of forming a Government. Given the arithmetic of the situation, we could not possibly embark on a proper Socialist programme."

G.D.H. Cole pointed out that MacDonald was in a difficult position. If he refused to form a government "it would have been widely misrepresented as showing Labour's fears of its own capacity, and it would have meant leaving the unemployed to their plight and - what weighed even more with many socialists - doing nothing to improve the state of international relations or to further European reconstruction and recovery." Left-wing members of the Labour Party suggested that MacDonald should accept office and invite defeat by putting forward a Socialist programme. The problem with that argument was the party could not financially afford another election, nor would they have been likely to win any more seats in the House of Commons.

Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become prime minister. He had the problem of forming a Cabinet with colleagues who had little, or no administrative experience. MacDonald's appointments included Philip Snowden (Chancellor of the Exchequor), Arthur Henderson (Home Secretary), John R. Clynes (Lord Privy Seal), Sidney Webb (Board of Trade) and Arthur Greenwood (Health), Charles Trevelyan (Education), John Wheatley (Housing), Fred Jowett (Commissioner of Works), William Adamson (Secretary for Scotland), Tom Shaw (Minister of Labour), Harry Gosling (Paymaster General), Vernon Hartshorn (Postmaster General), Emanuel Shinwell (Mines), Noel Buxton (Agriculture and Fisheries), Stephen Walsh (Secretary of State for War), Jimmy Thomas (Secretary of State for the Colonies), Ben Spoor (Chief Whip) and Sydney Olivier (Secretary of State for India).

John R. Clynes wrote in his Memoirs (1937): "An engine-driver rose to the rank of Colonial Secretary, a starveling clerk became Great Britain's Premier, a foundry-hand was charged to Foreign Secretary, the son of a Keighley weaver was created Chancellor of the Exechequer, one miner became Secretary for War and another Secretary of State for Scotland."

However, others claimed that the Labour Party had changed dramatically since before the First World War and had been taken over by middle-class elements. The German journalist, Egon Ranshofen-Wertheimer, pointed out: "The party which before the war had been a definite proletarian organisation in spite of intellectual leadership, became overrun by ex-Liberals, young-men-just-down-from-Oxford guiltless of any socialist tradition, ideologists and typical monomaniacs full of their own projects."

outside Buckingham Palace (23rd January, 1924)

On this day 1934 Lord Rothermere, the owner of the Daily Mail, published an article for his newspaper, Hurrah for the Blackshirts. Rothermere also gave full support to Oswald Mosley and the National Union of Fascists. On 15th January, 1934, he wrote: "At this next vital election Britain's survival as a Great Power will depend on the existence of a well-organised Party of the Right, ready to take over responsibility for national affairs with the same directness of purpose and energy of method as Mussolini and Hitler have displayed.... That is why I say Hurrah for the Blackshirts! ... Hundreds of thousands of young British men and women would like to see their own country develop that spirit of patriotic pride and service which has transformed Germany and Italy. They cannot do better than seek out the nearest branch of the Blackshirts and make themselves acquainted with their aims and plans." (259)

This was followed a few days later on 22nd January in which he praised Mosley for his "sound, commonsense, Conservative doctrine". Rothermere added: "Timid alarmists all this week have been whimpering that the rapid growth in numbers of the British Blackshirts is preparing the way for a system of rulership by means of steel whips and concentration camps. Very few of these panic-mongers have any personal knowledge of the countries that are already under Blackshirt government. The notion that a permanent reign of terror exists there has been evolved entirely from their own morbid imaginations, fed by sensational propaganda from opponents of the party now in power. As a purely British organization, the Blackshirts will respect those principles of tolerance which are traditional in British politics. They have no prejudice either of class or race. Their recruits are drawn from all social grades and every political party. Young men may join the British Union of Fascists by writing to the Headquarters, King's Road, Chelsea, London, S.W."

The Daily Mail continued to give its support to the fascists. George Ward Price wrote about anti-fascist demonstrators at a meeting of the National Union of Fascists on 8th June, 1934: "If the Blackshirts movement had any need of justification, the Red Hooligans who savagely and systematically tried to wreck Sir Oswald Mosley's huge and magnificently successful meeting at Olympia last night would have supplied it. They got what they deserved. Olympia has been the scene of many assemblies and many great fights, but never had it offered the spectacle of so many fights mixed up with a meeting."

In July, 1934 Lord Rothermere suddenly withdrew his support for Oswald Mosley. The historian, James Pool, argues: "The rumor on Fleet Street was that the Daily Mail's Jewish advertisers had threatened to place their adds in a different paper if Rothermere continued the pro-fascist campaign." Pool points out that sometime after this, Rothermere met with Hitler at the Berghof and told how the "Jews cut off his complete revenue from advertising" and compelled him to "toe the line." Hitler later recalled Rothermere telling him that it was "quite impossible at short notice to take any effective countermeasures."

On this day in 1953, Kathlyn Oliver, leader of the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain, died from a cerebral haemorrhage due to hypertension.

Kathlyn Oliver was born on 31 March 1884. According to her own account, her father "occupied a good position in the civil service", but unfortunately, "he did not think it necessary that his daughter should have a more than a very secondary education". When her father died and she had to earn her own living, domestic service was her only option.

Her biographer, Laura Schwartz, points out: "She loathed this work, resenting not just the low wages and long hours but also how she was constantly watched over and treated like a machine."

As a teenager she realised she was attracted to women. She fell in love with a girl of her own age when she was fourteen, and again when she was seventeen with a member of her Bible class. When she was in her early twenties she suffered a broken marriage engagement with a man. She later commented: "For reasons which it is unnecessary to explain here, we couldn't marry, and from the till now I have had to crush and subdue the sex feeling. As I said, this feeling awoke in me when I loved, but it never did, and it never will, govern me as it governs and enslaves the majority of men."

Oliver moved jobs seven times before finding "a reasonable and fair employer". Her life changed when she went to work for Mary Sheepshanks, principal of Morley College for Working Men and Women. Sheepshanks also was a leading speaker for the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Sheepshanks, allowed Oliver to organize her own work so that she had some evenings free to attend classes at Morley College and pursue her political interests.

Laura Schwartz pointed out in her book, Feminism and the Servant Problem (2019): "Kathlyn Oliver did not write much about her relationship with her mistress, Mary Sheepshanks, beyond expressing gratitude for allowing her evenings off to attend political meetings and classes at Morley College. Oliver and Sheepshanks moved in similar activist circles, both were socialists and pacifists as well as feminists."

About this time Kathlyn Oliver read The Jungle (1906) by Upton Sinclair, one of the leading socialist propagandists in the United States. In the book Sinclair described domestic work as "deadening and brutalising work, and ascribes to it anaemia, nervousness, ugliness and ill-temper, prostitution, suicide and insanity."

Oliver also started reading Woman Worker, a newspaper edited by Mary Macarthur, Secretary of the Women's Trade Union League. In 1909 Oliver joined a discussion already taking place in the correspondence pages of the newspaper, expressing her support for servants' demands for their own trade union. Macarthur encouraged her to organise such a trade union. In October 1909 she held a meeting to form a committee. Oliver made it clear that she wanted a union run by its members that would agitate for shorter hours and better food and accommodation for live-in servants, enforced by government legislation. The following month The Daily Mirror published a picture of Oliver and stated that she was going to be the general secretary of the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain.

Kathlyn Oliver claims that she was "besieged on all sides with letters from servants requiring information". The Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain (DWUGB) was officially launched in the spring of 1910, admitting both men and women members. Kathlyn Oliver became disillusioned with trying to recruit domestic servants into the DWUGB and handed over the role of general secretary to a domestic cook, Grace Neal.

However, she continued to give her support to the DWUGB. Kathlyn Oliver was aso a self-proclaimed feminist. She supported women's suffrage and was a member of the People's Suffrage Federation. In 1911 the organisation published Olivier's pamphlet, Domestic Servants and Citizenship (1911) In the pamphlet she argued that the living-in system should be abolished in favour of the state-employment or "nationalization" of domestic workers. She predicted that when domestic workers have the vote they will be regarded, with respect, and that when they are regarded with respect, "the conditions of the labour will speedily improve".

The pamphlet was reviewed by The Clarion, a socialist weekly, that had been established by Robert Blatchford, a Manchester journalist. The newspaper pointed out that Oliver "makes a striking appeal for the domestic servants' admission to the electorate". The reviewer added: "We are not sure that we agree with Miss Oliver that the mere occasion of a vote to domestic servants will necessary or even probably improve their conditions. She admits that the living-in system makes the organisation of servants practically impossible, and it seems to us the difficulty of organisation must be overcome before the vote can become an effective instrument for bettering their conditions. We would not oppose the granting of a vote to domestic servants, but we quail before the prospect of greasy canvassers pushing their political wares under the bewildered eyes of cook and parlour-maid at the tradesman door. We see no immediate solution of the difficulty, but we are quite sure that 'domestic service' is radically wrong. And we are unable to see that the vote would help matters."

Kathlyn Oliver also used The Common Cause the newspaper of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) to promote the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain. She was aware that a large number of NUWSS members employed servants but was unafraid to complain about the way servants were treated. In November 1911 she argued: "I think there can be little doubt that the entire system of domestic service needs revolutionising, or rather, nationalising. I know that few will agree, but I feel that on the present basis, with the present ideas, domestic work can never be entirely satisfactory, except perhaps for a few... The ideas which now make it possible for an employer to talk about allowing her domestic so much (or so little) freedom must be swept away, as well as the ideas which cause some employers to expect servility and bowing and scraping, in return for certain wages."

Employers of servants attempted to defend themselves. A fellow member of the DWUGB gave her support to Kathlyn Oliver: "I notice she tells us some ladies have said they allow their maids to go to bed at ten o'clock and one evening out a week, also alternate Sundays. Well, granted that is true, as it is in my experience, let us see what this means to the servant. In a fairly good place she has to get up not later than seven, and from that hour she is at the command of her mistress until ten o'clock at night, all the week through from Monday morning until Sunday night. When we average our time off one week with another it only averages eight hours a week, eleven one week and five the other, and should the lady be entertaining (which she often is) we are expected to give it up willingly, and if we did not, we should be marked as not obliging. Undoubtedly the domestic servant has many grievances, and the greatest of all is excessive hours of labour and too little time for recreation and self-culture."

Dora Marsden and Grace Jardine, worked for the Women's Freedom League newspaper, The Vote. However, they left and joined forces with Mary Gawthorpe to establish their own journal The Freewoman. The journal caused a storm when it advocated free love and encouraged women not to get married. The journal also included articles that suggested communal childcare and co-operative housekeeping. Marsden argued: "The publication of The Freewoman marks an epoch. It marks the point at which feminism in England ceases to be impulsive and unaware of its own features and becomes definitely self-conscious and introspective. For the first time, feminists themselves make the attempt to reflect the feminist movement in the mirror of thought."

Oliver was soon having her letters published in The Freewoman. At first she criticised the idea of free love. This resulted in her being attacked in the letters page. "I quite anticipated when I stated in your columns that abstinence had no bad effect on my health, I should be accused of not being normal. I have been told this before by another of the male persuasion. But from my knowledge of many single women and girls. I deny that I am not a normal woman. Of course, girls and women do not discuss the sex question as it affects themselves, but from my observation of unmarried girls and women whom I have known intimately, there is not the least ground to suppose that they are in any way troubled or affected diversity by complete chastity. I think I speak for most women when I say that until they love, the idea of the sex relationship seldom enters their thoughts, but if it does it appears repulsive rather than attractive."

Oliver explained that after a broken relationship she "had to crush and subdue the sex feeling." She added: "My intellect and reason rules my lower instincts and desires, and is this fact which raises me above the lower animals (including men). I repeat, these years of abstinence have not diversely affected my spirits. I become at times very morbid and depressed when I see life slipping by and youth going, going, going, and myself still loving, but unable to marry. Yes, at times it affects my spirits, but it will never affect my reason, because I have other interests and ideals in life, which are quite as real and as beautiful and as worth while as love and the sex relationship."

Kathlyn Oliver pointed out that her views on sex was linked to her political views: "As a suffragist and a feminist, I often talk at the equality of the sexes, but in sex matters it is surely indisputable that we women are miles above and beyond men. Some men would have us believe that their laxity in this matter and their inability or lack of desire to restrain or control their lower appetite is a sign of their superiority, but to me it only proves that, in spite of their advance in many directions, they have still a long way to go before they are really emancipated and evolved from the lower animal. But alas! They hug the chains which bind them."

Although she argued for chastity she admitted that she did not have conventional views on the subject of sex. In the Woman Worker she admitted that "I have been more in love with women than I have with any of the opposite sex… I cannot explain this (perhaps) unnatural state of things, but I know it is so". On another occasion she described herself as being of the "Intermediate sex", a term first used by Edward Carpenter.

Dora Marsden criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Kathlyn Oliver also discussed this issue with Stella Browne in the The Freewoman. Oliver claimed she had always practised chastity and that, contrary to what some of the new sexologists were claiming, this had in no way damaged her health. Oliver was also implicitly critical of the heterosexual bias of those who argued that sex with men was necessary to women's health. "Oliver was also implicitly critical of the heterosexual bias of those who argued that sex with men was necessary to women's well-being."

Dora Marsden attacked traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly."

Marsden's friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe. Stella Browne provided support for Marsden: "The sexual experience is the right of every human being not hopelessly afflicted in mind or body and should be entirely a matter of free choice and personal preference untainted by bargain or compulsion."

The Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain head office was at 211 Belsize Road, London and by January 1913 the union had acquired a regular subscribing membership of about 400 domestic servants. That year the Domestic Workers' Union joined forces with the Scottish Federation of Domestic Workers founded by Glasgow-based domestic servant Jessie Stephen. A member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) Stephen had started organizing maidservants in Glasgow into a domestic workers' union branch in 1912. She moved to London to work for the Domestic Workers' Union. Stephen was an active member of the Women Social & Political Union and helped to develop close links with both organisations.

On 28th January 1913, Margaret Macfarlane took part in an attempt to discuss women's suffrage with David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Organised by Flora Drummond and Sylvia Pankhurst, Macfarlane was apparently representing the demands of the Domestic Workers' Union. As Votes for Women explained: "Mrs Drummond led a deputation of working women from the Horticultural Hall to demand a further interview at the House of Commons with the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The interview was refused, and the women were treated with violence by the police. Mrs Drummond herself was knocked down and injured shortly after her emergence from the hall. Persisting, however, in her mission, she and a number of other women, including Miss Sylvia Pankhurst were taken into custody... Of the window-breakers. Miss Mary Neil was fined and ordered to pay the damage, or in default fourteen days; Miss Margaret Macfarlane was similarly dealt with, or in default fourteen days."

On 20th March 1913, Margaret Macfarlane was arrested again and charged with breaking two windows at the Tecla Gem Company, Ltd, Old Bond Street, Macfarlane sentenced to five months in the second division. The Suffragette reported that the Domestic Workers' Union held protest meetings about this sentence: "At a meeting organised by the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain in Trafalgar Square on Sunday, a resolution was unanimously carried, protesting against the sentence of five months imprisonment passed on Miss Margaret Macfarlane for her actions on behalf of domestic servants, and calling upon the government to release her immediately."

Kathlyn Oliver supported women's suffrage and was a member of the People's Suffrage Federation. Yet her advocacy of domestic servants' rights often led to clashes with the leaders of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). "She was quick to point out the hypocrisy of middle-class women who claimed to be working for the emancipation of their sex while exploiting their female servants. She insisted that the Domestic Workers' Union was there to represent the interests of the workers, rather than depend upon the goodwill of a handful of enlightened mistresses, and she did not attempt to deny accusations of advocating ‘class war' between women."

Although the leader of a trade union and critical of the middle-class nature of the women's suffrage organisations, Oliver realised that the servants' self-organization alone was enough to bring about the changes she desired, and she now preferred to "advocate the parliamentary vote as the best means of improving the conditions of domestic labour".

In June 1913 she became involved in the dispute between NUWSS and the WSPU. In a letter to The Daily Citizen, the newspaper of the Labour Party about the NUWSS unwillingness to break the law: "I quite fail to understand those suffragists who are always advertising the fact that they are law-abiding and constitutional. There is little virtue in being law-abiding when law breaking is so promptly punished, and little sense in being constitutional while the constitution is so obviously against women. These suffragists are always telling us how wicked and unfair the present laws are, and at the same time proudly brag that they are law-abiding. Surely it is more immoral to obey laws which we feel to be wrong than to break windows, etc. Whether law-abiding suffragists believe it or not, there are times when law-breaking becomes the only decent and moral thing. It is always moral to break the law without when it clashes with the law within."

This resulted in Louise Maude complaining about Kathlyn Oliver's support of the WSPU. She was quick to point out that was not the case as she was a pacifist: "I should like to explain, in answer to Mrs Aylmer Maude, that I did not intend, to back or support the militants. I abhor all kinds of violence. I merely wanted to point out that there is no essential virtue in law-abiding, and that legality and morality are not necessarily synonymous terms. With regard to the militants, is not the shocked attitude of the public on this question rather farcical when we remember that the same public permits what, in my opinion, is far worse than violence to property, viz., violence to little children in the form of corporal punishment? We allow with perfect calmness the flogging of children, but hold up our hands in horror when a woman breaks a window."

Kathlyn Oliver developed this point in a letter three months later: "I wonder if it has ever occurred to any of your socialist readers that, when they plead or demand that the majority shall rule, the present majority are on the side of everything which the true progressive would abolish? The majority today are at the back of everything which is harmful to humanity. They support the military spirit; they respect property far more than human life; they regard the humanitarian movement with amused contempt and the woman's movement either with contempt or active hostility. Socialism to the majority is either a dream of idealists or a vicious scheme, which they denounce whenever opportunity occurs. It is the minority which stands for morality and humanity, and I am proud myself to be in the minority."

Although not a member of the NUWSS she was willing to provide support against the actions of hostile men. In the summer of 1914 men were attempting to break-up their weekly Sunday afternoon meetings in Hyde Park. The Common Cause reported that at a meeting addressed by Kathlyn Oliver, Millicent Fawcett, Rosika Schwimmer and Inez Milholland helped to provide enough protection to make sure she was able to finish her speech.

Kathlyn Oliver was opposed to British involvement in the First World War. Along with other left-wing pacifists she formed the World Order of Socialism (WOS). Other members included Dora Montefiore, Walter Crane, Arthur St. John Adcock, James Keighley Snowden and Sir Francis Fletcher-Vane. The Daily Herald reported "All of these are Heraldites. There is hope for the WOS."

Oliver was appalled that leading figures in the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) such as Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were willing to play a prominant role in persuading men to join the armed forces. She was unaware that the WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August 1914 it was announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

Kathlyn Oliver was appalled by what she considered to be an act of betrayal. She later recalled: "As an animal welfare worker, I have had much experience of the average women's callousness and lack of imagination in connection with animal suffering. One remembers, too, how the gentle creatures hounded their men folk into the war, and no one was more pleased than I when continuous air raids gave these 'angels of pity' a little of what men suffered every hour of every day for three or four years."