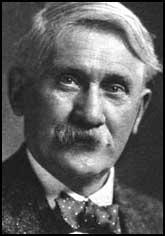

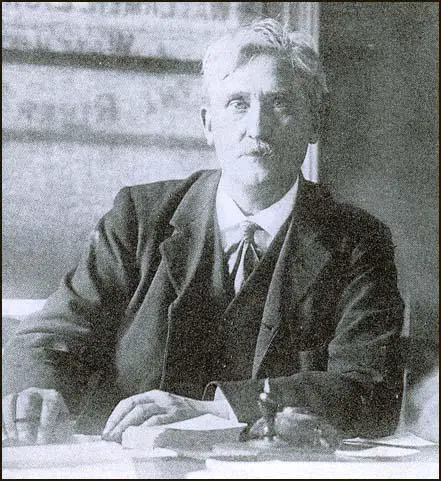

Harry Gosling

Harry Gosling, the second son of William Gosling, master lighterman, and his wife, Sarah Louisa Rowe, schoolteacher, was born at 57 York Street, Lambeth, on 9th June 1861.

He was educated at a school in Blackfriars where one master had the responsibility of teaching 250 children. Harry received help from his mother but she died in 1868. He later recalled in his autobiography: "It has been one of my lifelong regrets that my mother died when I was only seven, so that while I have never forgotten her beautiful eyes, my recollections of her are necessarily vague and dim. In many ways my life would probably have turned out differently if she had lived. She would have almost certainly tried to keep me off the river, for I was a very delicate child and began life as an individual who was not going to live."

Gosling left school at thirteen and found work as an office boy. The following year he was apprenticed to his father as lighterman, working on the barges of the Thames. In 1889 the successful London Dock Strike encouraged other workers to form unions. When the Amalgamated Society of Waterman & Lighterman (ASWL) was formed later that year, Gosling was one of the first to join.

In 1890 he became president of the Lambeth branch and a member of the union's executive council. Three years later he was elected to the full-time post of general secretary. Membership of the ASWL union was restricted to men who had served apprenticeships. However, an increasing number of men working on the Thames had been recruited without training. Gosling argued that unless these men were allowed to join, the union would remain weak. Most members were opposed to this and it was not until 1900 that they voted to allow non-apprenticed men into the union.

Harry Gosling was also active in local politics. He failed to be elected in 1895 to represent Rotherhithe on the London County Council (LCC). As be pointed out in Up and Down Stream (1927): I made my first attempt to secure election in 1895, when I fought Rotherhithe as a Labour-Progressive. Sir Howell VVilliams, who had been successful in a by-election in the previous year, was my colleague in this contest. His success had so encouraged the Progressives that they determined to make a bid for both seats, and they thought a trade union candidate would be a good asset in such a constituency... But I am sorry to say we lost the election, and that largely because my union, the Amalgamated Society of Watermen and Lightermen, which was financing me, would not vote for me. No, this is not a conundrum, but was quite an ordinary occurrence in those days, and it still happens even now. My union financed me because the men wanted to be represented by one of their craft when river problems came up on the London County Council, but they refused to vote for me because the exercise of their craft had made them Tory in outlook, or at best politically apathetic. In one way and another this strange contradiction runs through the trade union move."

In 1898 Gosling did receive an alderman's seat and joined other trade union leaders such as John Burns and Will Crooks, supporting the ruling Progressive Group on the London County Council. In 1904 he was elected to the LCC when he stood for the waterside constituency of Wapping. Four years later Gosling also won a place on the influential Trade Union Congress parliamentary committee.

In July 1910 Ben Tillett, the leader of the Dockers' Union, called a meeting with other waterside unions to discuss the possibility of forming a National Transport Workers' Federation (NTWF). The representatives of the sixteen unions present at the meeting agreed and Harry Gosling was elected president of the new organisation. In 1911 attempts to negotiate union recognition and a uniform scale of payment throughout the port ended in failure and a NTWF strike. This was called off when agreement was obtained at the end of August. The relationship between the NTWF remained poor and another strike took place in May 1912. This was less successful and at the end of July the men were forced back to work without achieving their objectives.

Gosling continued to argue for further amalgamation and in June 1913 the General Labourers' Union joined the NTWF. The organisation was considerably strengthened by the election of Ernest Bevin to the executive. Gosling and Bevin worked closely together in their efforts to make the NTWF a powerful union. Later, the two men were instrumental in establishing the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU).

The Labour Party was unable to gain control of the London County Council during this period. However, in November 1919, the party won 39 of the 42 council seats on Poplar Council. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury, the new mayor of Poplar, proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie Lansbury said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury, Edgar Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council were now put in a difficult position. Harry Gosling volunteered to negotiate a settlement. As he later recalled: "The actual drafting of the document was no easy matter with such critics as George Lansbury and his son Edgar, Susan Lawrence, John Scurr, and all the others round the table, ready to object at any chance word and upset the whole thing in their eagerness to uphold their cause. Every one of these men and women stood for what was in their view a great principle, and yet a formula had to be found to enable the judges to release them."

On 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

Gosling made several attempts to enter the House of Commons. He failed to win Lambeth in the 1922 General Election, but was returned at a by-election at Whitechapel in February 1923. In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. MacDonald had the problem of forming a Cabinet with colleagues who had little, or no administrative experience. MacDonald's appointments included Gosling as Minister of Transport. A post he held until the fall of the MacDonald government in October, 1924.

Marc Brodie has pointed out: "During the first Labour government, in 1924, he was minister of transport and paymaster-general, and was responsible for the London Traffic Act (1924). On the fall of the government, Gosling sought to regain the presidency of the TGWU which he had resigned on becoming a minister, but was blocked by the union council. The decision provoked an outcry which led to its being reversed - an indication of the loyalty and respect that Gosling had built up within the union."

In 1927 Gosling published his autobiography, Up and Down Stream. Harry Gosling remained in the House of Commons until his death at his home, Goodfetch, Waldegrave Road, Twickenham, on 24th October 1930, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium.

Primary Sources

(1) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

My grandfather and father likewise worked for themselves as master lightermen in a smaller way of business. Their main work was to tow rafts of timber from Scandinavian sailing vessels in the Surrey Docks to builders' yards along the shore where the County Hall now stands. The rafts were towed by rowing boats or skiffs, and when I in my turn joined them at the ripe age of fourteen, my grandfather and I rowed in one boat, because we were supposed to combine the skill and the strength which my father, rowing alone in another, united in himself. I worked in my grandfather's boat just as he had worked in his grandfather's, and for the same reason: it was a matter of family routine.

Grandfather always wore a top hat, at work or at rest, and in every kind of weather. He would wear it in a hurricane, and I never once remember it blowing off. He always carried a small steel comb in his pocket, and he would do his hair a hundred times a day, and even stop rowing to do it. When pilot caps came into fashion he could not get down to them, but always remained a top-hat man. He was one of those methodical old fellows who took life very quietly and never got ruffled. He was fond of me in a grandfatherly way, and as a boy I went to see him nearly every Sunday, when he would give me a penny and some cherries when they were in season. But he didn't like visitors to stay late, and one of my very early recollections is his starting to wind up the clock to give late stayers a hint that it was time to go.

My father was a man of far more varied interests than my grandfather. He did not speculate or adventure in his trade, but worked hard and steadily at it because he had a wife and children to keep. In everything else he was a dreamer and a philosopher, and not a shrewd man of business. I remember rowing in the boat with him all through one long, starry night. Neither of us spoke. Only once he left off rowing for a moment, turned to me as I was sitting behind him, put his hand on my knee, and pointed up to the sky: "That's what licks us." He always seemed to have a strange and puzzled consciousness of our human littleness as compared with the greatness of the universe.

He was most careful and economical in everything, and would never buy anything unless he could pay ready money for it. I have never known him to take goods on account. I remember one day I had been sent to the baker to buy bread, a serious item in a large family, and he sent me back to the shop with it because it was not the proper weight. He always kept his own scales to test things with, which was a wise precaution in those days before the Weights and Measures Act had been passed. He was a model father and husband and did everything in his power for us all. I attribute most of the good things that have happened to me to my luck in having had good parents.

My mother was a school-teacher who had been trained at the Borough Road Training College and had got her certificate from there. That was in those days looked upon as the hall-mark of the teaching profession. She went on teaching after she was married, and took her first baby to school with her to be able to look after it between whiles.

My father used to tell me how on one occasion on a high spring tide the water flowed across the York Road. This, of course, was abnormal, it being considered a very high tide if Belvedere Road was covered. As it was about the hour when the school closed, my father rowed his boat through the wharf, across Belvedere Road, right up Guildford Street, and across the York Road to the school gate to meet my mother, who was not a little surprised to see him. He rowed her back to the Belvedere Road and helped her through the window of the " Guildford Barge," an inn that stood on the corner of the street of that name.

It has been one of my lifelong regrets that my mother died when I was only seven, so that while I have never forgotten her beautiful eyes, my recollections of her are necessarily vague and dim. In many ways my life would probably have turned out differently if she had lived. She would have almost certainly tried to keep me off the river, for I was a very delicate child and began life as an individual who was not going to live. But as time went on the doctors kept postponing the date of my death and my father was persuaded that an open-air life would be the best to strengthen and build me up. It was true to a certain extent, but the work was too heavy and resulted in a series of breakdowns later on.

(2) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

I went to school at Marlborough Street, now known as Grey Street in the New Cut, Waterloo Road. The school was under the British and Foreign School Society, but when the Education Act of 1870 was passed it was taken over by the School Board and rebuilt, and for the first time in his life the head master had an assistant. When I went to school at the age of five he was in sole command of two hundred and fifty boys of all ages. He appears to me now as a kind of chairman of a permanent mass meeting.

I wish I could get a plan of the old building; it would surprise people nowadays. It was just a long, narrow hall with no classrooms or partitions even. At one end there was a raised platform running the whole width of the hall with about eight steps on each side leading up to it and a long rail in front. In the middle of the platform stood a desk at which the master sat, and always with his cane under his arm. The forms at which we sat were fixed to the floor and had no backs. They had little desks in front of them, about half the width of the slates we wrote on. The seats were very narrow, and if one did not sit well forward it was easy to catch a crab. No paper was used in my time. Boys cleaned their slates by spitting on them

and rubbing them with their caps or sleeves. There was no other way of doing it. A few of the scholars from particularly respectable homes had a little sponge tied on to their slates, but their parents must have been well in advance of the times; also, the sponges never lasted long. A gangway ran down each side of the building. Right in the centre was a closed-in stove for heating purposes. There was no other source of heat. When we stayed for dinner, as we sometimes did, we used to get a beer can and boil chestnuts in it when they were in season.

Across one corner of the school building ran a gallery for the accommodation of the very small boys. I have often wondered since what those very small boys ever learned on that gallery. My only recollection is of a big boy looking after them. Every Friday afternoon, year in year out, the master used to place a chair in front of the stove and one of the best readers would stand up on it and read. One-half of the boys turned round to lean against their desks and the selected boy read aloud from some standard book. When he had done his bit, he passed the book to another good reader, and so on, for the boys did not have a copy each as they have now. In the meantime the master walked round with his cane. Naturally the dilatory and ignorant boys were not very interested in the reading, and especially on hot days were inclined to fall asleep. When this happened the master would get a glass of water, dip his cane into it, and let the water drip into the boy's ear. Not a single boy dared to laugh at this quaint form of punishment.

The master was a very keen sportsman and taught the boys cricket. As there was no playground, and, by the way, no playtime either, we practised before and after school hours in one of the five-foot gangways that ran down the hall, with a soft ball and three stumps fixed in a block of wood.

He also taught us to read the Bible, this being practically the only religious instruction given. It was his boast that he never had a difficulty with parents on religious matters, though this was a frequent problem in those days.When I was monitor I sometimes took charge of the gallery and in this way avoided the necessity of doing home lessons. The fees for attending the school were twopence per week for ordinary classes and fourpence for the first class. If a pupil did not bring the fee with him he was sent home for it. The curriculum consisted of reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and geography. There was also a voluntary singing class to which we contributed a halfpenny per week.

Every Guy Fawkes Day the master rigged up a little toy cannon on his desk and fired it off. The boys gave three cheers and sang the National Anthem after he had related the story. There was what would now be called a thoroughly good tone in the school, for the great thing Mr. Strong taught us was to "play the game," and sneaking was not thought of. Before dispersing on Friday afternoons the scholars always sang:

"Childhood years are passing over us, youthful days will soon be gone. Cares and sorrows lie before us, hidden dangers, snares unknown."

A solemn peep into an adventurous yet gloomy future !

(3) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

The first Friday afternoon, when I was thirteen years old, on my way home from school I saw a bill in the window of the offices of Messrs. Thomas Lambert & Sons in Short Street in the New Cut, announcing that an office boy was wanted. As I knew this firm had recruited their office boys from our school for many years I went in, and got the job. On my way home, I met my father returning from work and told him I was going to work next Monday. He was surprised and said: "Going to work? What do you mean? Who said you could go to work?" I explained to him that Lamberts' wanted an office boy and had engaged me. He wanted to know how I intended to get a character, and I said I would get one from Mr. Strong, the schoolmaster, and was going to see him about it in the morning. My father tried to pull my leg and pretended he was not so sure about my deserving one. I think he was rather taken aback by the whole affair and by my impulsive action. Somehow, it had never occurred to me that I ought to get my father's permission to leave school and go to work. I have always liked doing things independently, and all my life I have never felt anything else but free.

I got an excellent reference from Mr. Strong, which I duly presented to my future firm, and on the Monday morning I began my work at a salary of six shillings per week. My job was to write out envelopes and stick on stamps, and I thoroughly enjoyed it for a time. Then suddenly it struck me that I ought to have a rise, and I saw the governor and told him so. He said I had not been there twelve months, but he would think about it. That was not good enough, I said; if I could not have a rise I would get my father to apprentice me. To what? To the river, I explained. "Well, of course, I don't know anything about that," answered my employer, implying there would be other boys to do the work if I chose to leave.The result of it all was that my father really did apprentice me to the river when I was fourteen.

(4) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

I served on the London County Council for twenty-seven seven years, and though all that time I was one of a very small minority party, I have many pleasant memories of my association with the world's greatest municipal authority.

I made my first attempt to secure election in 1895, when I fought Rotherhithe as a Labour-Progressive. Sir Howell VVilliams, who had been successful in a by-election in the previous year, was my colleague in this contest. His success had so encouraged the Progressives that they determined to make a bid for both seats, and they thought a trade union candidate would be a good asset in such a constituency. At the first public meeting which we attended together Sir Howell J. Williams had to introduce me and vouch for my integrity as a new-comer. He assured the audience he had made careful inquiries and found I was a most respectable young man with whom he was quite content to be associated. But I am sorry to say we lost the election, and that largely because my union, the Amalgamated Society of Watermen and Lightermen, which was financing me, would not vote for me.

No, this is not a conundrum, but was quite an ordinary occurrence in those days, and it still happens even now. My union financed me because the men wanted to be represented by one of their craft when river problems came up on the London County Council, but they refused to vote for me because the exercise of their craft had made them Tory in outlook, or at best politically apathetic. In one way and another this strange contradiction runs through the trade union movement still, and is responsible for considerable waste of force in our ranks...

When I first came on to the Council in 1898 we were a Labour group of eight: John Burns, Will Steadman a barge builder, Will Crooks a cooper, George Dew a carpenter and joiner, Charles Freak a bootmaker, Harry Taylor a bricklayer, Ben Cooper a cigarmaker, and myself. Finance was still a considerable difficulty. Three of us - Burns, Crooks, and Steadman - depended upon so-called "wages funds" which were raised for their benefit in Battersea, Stepney, and Poplar respectively.Most of the members of these committees were trade unionists, and they had to devise ways and means of raising money to pay weekly wages to their representatives. These were not always forthcoming, and Steadman fared particularly badly. He was the secretary of the Barge Builders' Union, but as they never numbered more than three or four hundred, they were quite unable to pay him a salary, and all he received was a small payment for part-time services. He was also the secretary of our London group on the Council and used occasionally to come round for a subscription to the party fund to meet his expenditure on postage and stationery.

With our lives and previous experiences we were all at first far more keenly interested in the industrial than the political side of things, and even in our impressive environment at Spring Gardens there was no question of a sudden rush of feeling for politics as such. But that political sense could not fail to grow steadily and healthily all the time, for as all parties have recognized by now there is no better training ground for anyone than the London County Council.

From the very beginning our little party on the London County Council kept its identity as a distinct Labour group. We had our own party meetings and decided our own course of action on the Council agenda, and though we have in later years been taunted with our Progressive connections I still maintain that we were one of the first live Labour parties on any public authority.

(5) Herbert Tracey, The Book of the Labour Party (1925)

Those qualities of leadership that had earned for him the confidence of his fellow-workers were put to the sternest possible test by the great transport strike of 1911. He was called upon to act as chairman of the Strike Committee, and the success with which he acquitted himself in the face of enormous difficulty is now a matter of history. It is generally recognised that to the efforts of Gosling and his colleague Ben Tillett are largely due the successful issue to which the dispute was carried, resulting in the first agreement governing conditions of port labour being secured. Another dispute in which he took a leading part was the London Transport Strike of 1912, whilst he was also one of the members of the Court of Inquiry, presided over by Lord Shaw in 1920, which worked out the new Dockers' Settlement, and of the Court of Inquiry into the Tramways Industry in the same year.

He continued to act as President of the Transport Workers' Federation until 1921, when, on the formation of the Transport and General Workers' Union- the largest organisation of transport workers in the country--he was almost automatically elevated to the presidency of the new body. On entering the Ministry when the Labour Government was formed, he resigned from the position, but on the completion of his term of office lie was invited to return.

Amongst his other activities, it may be mentioned that since 1909 he has been a member of the Port of London Authority, he has served on the Civil Service Arbitration Board, and when the Industrial Council was formed in 1911 he became one of the Trade-Union representatives. During the War his services were in great demand, and he devoted himself assiduously to many of the war-time committees, notably the War Graves Commission, the Special Grants Committee of the Ministry of Pensions, the Belgian Refugees' Committee, Lord Balfour of Burleigh's Committee on Industrial Policy, and the Port and Transit Executive Committee, the body that was charged with the regulation of all incoming and outgoing vessels. His work on this committee was specially praised in the House of Commons by the Prime Minister of that time - Mr. Asquith and he was invested with the Companionship of Honour in recognition of his services.

(6) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

What an extraordinary drama it was, with its secret messages, its nocturnal meetings in prison board rooms, its almost miraculous yielding of prison bars! It would have made a splendid Bolshevik play, only it was so essentially British that no other country but our own could possibly have produced it. But it is all very well to jest: the Poplar problem has not been solved nor ever will be by any melodrama, however daringly conceived and played. The bitterness, the want and suffering which is at the root of it all will remain with us until men and women have learned what Socialism has to teach. Feeling and fighting does its bit, but collective thinking and the intelligent application of thought to social life are better and stronger weapons by far.

Let me tell the story of Poplar as I remember it, for quite contrary to my inclination I had a remarkable part to play in the drama.

The slump after the war found many of the East End boroughs in a pretty bad plight. The high cost of living and the increasing amount of unemployment were reflected in the rates, which rose to hitherto unheard-of heights. In Poplar particularly the position had become unbearable, and the Borough Council found themselves faced with precepts from the London County Council, the Metropolitan Police, and the Metropolitan Asylums Board due for payment before September 30, 1921, amounting to no less a sum than £195,52 18s. The local rate was already equal to 18s. 1d. in the pound exclusive of the precepts mentioned, which would amount to another 9s. 2d. in the pound, or 27s. 3d. in all. This was in striking contrast to the wealthier parts of London. In Hampstead, for instance, the total rate was 12s. 9d. in the pound, while in Westminster it was 11s. 1d.

For many years an agitation had been going on for an equalization of rates over the whole county of London which, if adopted, would have meant a rate of 16s. 6d. for Poplar in this particular year. Nothing of any substance had been done in this direction, however, and the borough councillors felt the time had come when something drastic must happen in order to focus attention "on the glaring injustice of the existing system." So they decided to refuse to levy rates for the central authorities, and only the rates for local purposes were collected.

This action caused the greatest consternation everywhere ; a number of conferences took place between the Minister of Health (Sir Alfred Mond) and the bodies I have mentioned; and finally the London County Council decided to apply for a mandamus compelling the Poplar Borough Council to function. Legal formalities were proceeded with and summonses were issued against the revolting councillors, who responded by marching in state to the Law Courts with the Deputy Mayor (Charles Key) and the mace at their head, to show cause, etc., in truly legal style. An order was made upon them as well, and their appeal went against them too. They then refused to obey the order, and the County Council, having once put its hand to the business, had to go on, and the rebels were committed to jail for contempt of court.The twenty-five men, including the Mayor (Sam March, L.C.C.), were sent to Brixton Prison, and the five women-Miss Susan Lawrence, L.C.C., Mrs. Minnie Lansbury, Mrs. Julia Scurr, and Mrs. Cressall - were sent to Holloway.

The Minister of Health and the London County Council were thus temporarily triumphant: the majesty of the law had prevailed and the Poplar Borough Council was its prisoner!

It is obvious that no members of a public authority can act individually - they must act collectively - and the whole object of the Poplar Council certainly was to secure collective action. But in prisons collective action is unknown. Such care is taken to preserve the individuality of prisoners that they are actually kept in separate rooms.So we now had the position that nobody could speak for the Borough Council, and yet it was unable to speak for itself. It was bad enough that the councillors were in separate cells, but when the cells were in two separate prisons on opposite sides of London what was to be done? This kind of thing might have gone on for ever!

As a matter of fact it became evident soon enough that although it had been a tedious business and had taken a long time to put them safely under lock and key, this was a comparatively simple task compared with getting them out again. And, after all, it would have to happen some time or other.

The Minister of Health was no doubt by this time being asked questions in Parliament as to what he proposed to do, and no doubt he in turn reminded the chairman of the London County Council that his precious body had brought all this about and asked him what he proposed to do? Apparently the suggestion of the chairman was that Sir Alfred Mond should send for me!

He did so and, obviously in dire despair, told me all his difficulties, how these troublesome borough councillors had got put into jail, and now nobody seemed to know how to get them out, and could I possibly do anything? I said I would do what I could, and volunteered to go and see the rebels.

But there were the prison gates, and there were the locked cells, and a hundred difficulties besides, which for the moment seemed to make any progress in the matter impossible. I went to Brixton and asked to see the Mayor of Poplar, and intimated to the Governor that I wanted to see the twenty-four other councillors as well. But he pointed out that that would take practically the whole day. I told him that as I had promised to do something I would not let time stand in my way ; would it not be possible for me to see them all at once? By way of reply he read to me so many regulations that I began to wonder if I should ever see any of them at all!

(7) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

The London County Council called its special meeting on October 4th, to which I have already alluded. The Metropolitan Asylums Board also indicated that they would offer no opposition to any application for the release of the imprisoned councillors. The Ministry of Health proposed a conference to consider the equalization of London rates, a most valuable suggestion in itself, but obviously requiring the presence of the Poplar representatives, especially as the other London Labour boroughs had refused to submit proposals for discussion at the conference unless the Poplar people were set free.

And all the time Mathew and Thompson were thinking their hardest, with the triumphant result that after another late sitting of the Borough Council in the Brixton board room an apologetic formula was evolved and actually approved by all the thirty prisoners.

I cannot express my sense of relief when it was all over. The actual drafting of the document was no easy matter with such critics as George Lansbury and his son Edgar, Susan Lawrence, John Scurr, and all the others round the table, ready to object at any chance word and upset the whole thing in their eagerness to uphold their cause. Every one of these men and women stood for what was in their view a great principle, and yet a formula had to be found to enable the judges to release them.The prisoners were discharged on this affidavit, and the solicitor and I received the orders and went to Holloway first. The women came across to Brixton with us and waited for the men, who had to be collected up, receive their belongings, and give the proper receipts, while the governor worried round us all the time in the utmost anxiety that there should be no noise because it would disturb the rest of the other prisoners. We left the prison with the greatest enthusiasm among the members of the Poplar Borough Council and no small satisfaction on the part of my colleague and myself in having helped to straighten out this most unusual tangle.

(8) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

In February, 1924, under the Labour Government, I was called to the Ministry of Transport, and my period of office lasted till September of that year.

As Minister of Transport I was housed in Whitehall Gardens, an extraordinarily interesting site, and I added considerably to my knowledge of history while I was there. One does when one lives on the spot, and has, moreover, quite a number of expert antiquarians on one's staff. The house actually occupied by the Ministry of Transport - No. 5 - was built about 1824, and was at one time the residence of Sir Robert Peel, who died on July 2, 1850, in the large room on the ground floor facing the river.

The functions of the Ministry of Transport are said to involve more administrative work, as distinct from other types of labour, than the majority of Government offices. Its field includes powers and duties relating to railways, light railways, tramways, canals, waterways, and inland navigation, roads, bridges, and ferries and vehicles and traffic thereon ; also harbours, docks, and piers.