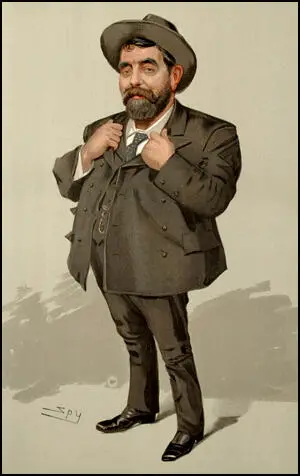

Will Crooks

William Crooks, the son of a ship's stoker, was born in a one-room house Poplar, East London, on 6th April, 1852. When he was three years old, William's father lost an arm when a ship's engine was started when he was oiling the machinery. Unable to find regular work because of his disablement, the family had to rely on the earnings of Mrs. Crooks work as a seamstress.

In 1861 Mr. Crooks and the five youngest children, including William, were forced to enter the Poplar Workhouse. Eventually Mrs. Crooks was able to find enough work and a cheaper room and the family were reunited. These experiences had a dramatic impact on Crooks and helped to influence his strong views on poverty and inequality.

Mrs. Crooks, despite being illiterate herself, encouraged her children to go to school. Although always short of money, Mrs. Crooks found the penny a week needed to educate William at George Green School on the East India Dock. She was also a deeply religious woman and the whole family attended the local Congregational Church.

As soon as he was old enough, William found work as a errand boy at a grocer's for two shillings a week. This was followed by a period as a blacksmith's labourer, but in 1866 Mrs. Crooks was able to arrange for the fourteen year old William to be apprenticed to a copper. Crooks was an avid reader and as a teenager discovered the works of Charles Dickens. He also began reading radical newspapers and found out about the campaigns of reformers such as John Bright and Richard Cobden.

Crooks impressed his fellow workers were impressed with his knowledge and asked him to speak to their boss about the excessive overtime they had to work. Crooks agreed to do this but as a result of the meeting he was sacked as a political agitator. Crooks, whose young wife had just had their first child, was forced to leave the area in search of work. Eventually Crooks found work in Liverpool. His family joined him but within a month his child died and Crooks and his wife returned to London.

Crooks found work as a casual labourer at East India Docks. Every Sunday morning he gave lectures on politics at the dock gates in Popular. Subjects of his lectures, at what became known as Crooks' College, included trade unionism, temperance and co-operative societies. John Robert Clynes later recalled: "Will Crooks combined the inspiration of a great evangelist with such a stock of comic stories, generally related as personal experiences, that his audience alternated between tears of sympathy and tears of laughter. I know of no stage comedian who can move his audience today to such roars of merriment as could Will Crooks, when he related the human incidents that formed so valuable a part of his platform stock. I once heard him say that a non-Union workman who tried to gain personal advancement at the expense of his mates was like a man who stole a wreath from his neighbour's grave and won a prize with it at a flower show!"

When the London Dock Strike started in August 1889, Crooks used his considerable skills as an orator to help raise funds for the dockers. Over the next few weeks Crooks emerged with Ben Tillett, Tom Mann and John Burns as one of the four main leaders of the strike. The employers hoped to starve the dockers back to work but other trade union activists such as Will Thorne, Eleanor Marx, James Keir Hardie and Henry Hyde Champion, gave valuable support to the 10,000 men now out on strike. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Labour Church raised money for the strikers and their families. Trade Unions in Australia sent over £30,000 to help the dockers to continue the struggle. After five weeks the employers accepted defeat and granted all the dockers' main demands.

The London County Council (LCC) was created as a result of the 1888 Local Government Act. The LCC was the first metropolitan-wide form of general local government. Crooks became Progressive Party candidate for Poplar. Elections were held in January 1889 and the Progressive Party, won 70 of the 118 seats. Crooks won in Popular and other leaders of the labour movement including Sidney Webb John Burns and Ben Tillett, joined him in the LCC.

In 1892 Crooks' wife died, leaving him with six children. A year later he married Elizabeth Lake, a nurse from Gloucestershire. Crooks became chairman of the Public Control Committee and in this post promoted fair wages for LCC employees and the Infant Life Protection Bill which ended baby-farming in London. Crooks also became the first working-class member of the Poplar Board of Guardians.

Crooks became chairman of the Board of Guardians in 1897 and with the aid of his fellow member and friend, George Lansbury, began the task of reforming how the Popular Workhouse was run. Corrupt and uncaring officials were sacked, and the food and education that the inmates received were improved. Every effort was made to find homes for the young orphans in the workhouse. Crooks and Lansbury were so successful that the Poplar Workhouse became a model for other Poor Law authorities.

Crooks also became a member of the Poplar Borough Council and in 1901 became the first Labour mayor of London. He also helped establish the National Committee on Old Age Pensions. Influenced by the ideas first expressed by Tom Paine in The Rights of Man, Crooks believed that pensions were the only way to keep the elderly poor from entering the workhouse.

In 1903 the Labour Representation Committee invited Crooks to stand as their candidate in a by-election in Woolwich. Crooks had made many friends in the Liberal Party during his time on the London County Council and they withdrew their candidate from the election. During the campaign Crooks argued against the Taff Vale decision and the 1902 Education Act and urged the government to take measures to help the unemployed and those workers on low wages. Although normally a safe Conservative seat, the support of the Liberals enabled Crooks to obtain an easy victory.

After his election Crooks continued to live in his house in Poplar. He argued that it was important that he continued to retain his links with the working-class. In the House of Commons Crooks concentrated on the issue of unemployment. He supported the Unemployment Bill introduced by Arthur Balfour in 1905 and controversially advocated compulsory agricultural work for the able-bodied unemployed.

Crooks was re-elected in the 1906 General Election and for the next four years supported the reforming Liberal administrations led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1906-1908) and Herbert Asquith (1908-1910). Will Crooks was defeated in the January 1910 General Election but returned to the House of Commons in the election held in December, 1910.

Unlike most of the leaders of the Labour Party, Crooks enthusiastically supported Britain's involvement in the First World War. He participated in the recruiting campaign and toured the Western Front in an effort to boost the morale of troops. In one speech Crooks declared that he "would rather see every living soul blotted off the face of the earth than see the Kaiser supreme anywhere."

Crooks won the seat in the 1918 General Election but he was forced to retire from his seat in February 1921, due to ill-health. Will Crooks, who had never moved away from his house in Poplar, died in London Hospital, Whitechapel, on the 5th June, 1921.

Primary Sources

(1) John Robert Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

Will Crooks combined the inspiration of a great evangelist with such a stock of comic stories, generally related as personal experiences, that his audience alternated between tears of sympathy and tears of laughter. I know of no stage comedian who can move his audience today to such roars of merriment as could Will Crooks, when he related the human incidents that formed so valuable a part of his platform stock. I once heard him say that a non-Union workman who tried to gain personal advancement at the expense of his mates was like a man who stole a wreath from his neighbour's grave and won a prize with it at a flower show!