On this day on 28th January

On this day in 1547 Henry VIII died. He had been in poor health for sometime and he was under pressure to have his sixth wife, Catherine Parr, execued. In February 1546 conservatives, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, began plotting to destroy Catherine. Gardiner had established a reputation for himself at home and abroad as a defender of orthodoxy against the Reformation. On 24th May, Gardiner ordered the arrest of Anne Askew and Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, was ordered to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine and other leading Protestants.

The Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack, after Kingston complained about having to torture a woman. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." On 16th July, 1546, Askew "still horribly crippled by her tortures but without recantation, was burnt for heresy".

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII and raised concerns about Catherine's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible.

David Loades has explained that "the greatest secrecy was observed, and the unsuspecting Queen continued with her evangelical sessions". However, the whole plot was leaked in mysterious circumstances. "A copy of the articles, with the King's signature on it, was accidentally dropped by a member of the council, where it was found and brought to Catherine, who promptly collapsed. The King sent one of his physicians, a Dr Wendy, to attend upon her, and Wendy, who seems to have been in the secret, advised her to throw herself upon Henry's mercy."

Catherine Parr told Henry that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse.

The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe, a leading Protestant at the time. However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women."

Henry's health continued to cause concern. According to Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012), Henry's private secretary, William Paget, became a powerful influence upon the ailing king. Ackroyd suggests that Paget associated himself with the reformers in the king's council. In the autumn of 1546 the imperial ambassador, described the unexpected rise in the influence of religious reformers: "The Protestants have their openly declared champions... some of them had gained great favour with the king, and I could only wish that they were as far away from court as they were last year."

As Paget's biographer, Sybil M. Jack, has pointed out: "William Paget... had become one of the most powerful office-holders in the kingdom. He spoke for the monarch, controlled considerable patronage, and was the linchpin both of Henry's diplomatic correspondence and the national intelligence network. It was Paget's job to sift out from the intercepted mail and oral communications real plots from imaginary or invented ones, to distinguish reliable from double agents."

Dr. George Owen, the royal physician, who was paid £100 a year to treat the king, told the Privy Council in December, 1546, that Henry was dying. The Privy Council, now under the control of religious radicals such as John Dudley, Edward Seymour and Thomas Seymour decided to keep the news secret. On 24th December, Catherine took Mary and Elizabeth to stay at Greenwich Palace for the holidays. On their return they were told that Henry was too ill to see them.

Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. The following day Edward and his thirteen year-old sister, Elizabeth, were informed that their father had died. According to one source, "Edward and his sister clung to each other, sobbing". Edward VI's coronation took place on Sunday 20th February. "Walking beneath a canopy of crimson silk and cloth of gold topped by silver bells, the boy-king wore a crimson satin robe trimmed with gold silk lace costing £118 16s. 8d. and a pair of ‘Sabatons’ of cloth of gold."

On this day in 1839 George Julian Harney makes important speech on universal suffrage. Harney argued: "We demand Universal Suffrage, because we believe the universal suffrage will bring universal happiness. Time was when every Englishman had a musket in his cottage, and along with it hung a flitch of bacon; now there was no flitch of bacon for there was no musket; let the musket be restored and the flitch of bacon would soon follow. You will get nothing from your tyrants but what you can take, and you can take nothing unless you are properly prepared to do so. In the words of a good man, then, I say 'Arm for peace, arm for liberty, arm for justice, arm for the rights of all, and the tyrants will no longer laugh at your petitions'. Remember that."

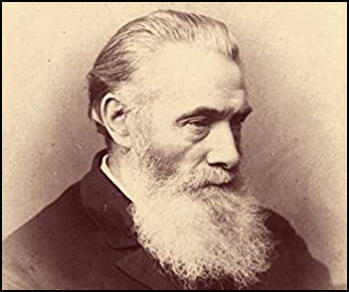

George Julian Harney, the son of a seaman, was born in Depford on 17th February, 1817. When Harney was eleven he entered the Boy's Naval School at Greenwich. However, instead of pursuing a career in the navy he became a shop-boy for Henry Hetherington, the editor of the Poor Man's Guardian. Harney was imprisoned three time for selling this unstamped newspaper.

This experience radicalized Harney and although he was initially a member of the London Working Man's Association he became impatient with the organisation's failure to make much progress in the efforts to obtain universal suffrage. Harney was influenced by the more militant ideas of William Benbow, James Bronterre O'Brien and Feargus O'Connor.

In January 1837 Harney became one of the founders of the openly republican East London Democratic Association. Soon afterwards Harney became convinced of William Benbow's theory that a Grand National Holiday (General Strike) would result in a uprising and a change in the political system.

At the Chartist Convention held in the summer of 1839, Harney and William Benbow convinced the delegates to call a Grand National Holiday on 12th August. Feargus O'Connor, argued against the plan but was defeated. Harney and Benbow toured the country in an attempt to persuade workers to join the strike. When Harney and Benbow were both arrested and charged with making seditious speeches, the General Strike was called off. Harney was kept in Warwick Gaol but when he appeared at the Birmingham Assizes the Grand Jury refused to indict him.

Disappointed by the failure of the Grand National Holiday, Harney moved to Ayrshire, Scotland, where he married Mary Cameron. Harney's exile did not last long and the following year he became the Chartist organizer in Sheffield. During the strikes of 1842 Harney was one of the fifty-eight Chartists arrested and tried at Lancaster in March 1843. After his conviction was reversed on appeal, Harney became a journalist for Feargus O'Connor's Northern Star. Two years later he became the editor of the newspaper.

Harney became interested in the international struggle for universal suffrage and helped establish the Fraternal Democrats in September 1845. It was through this organisation that Harney met Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Harney persuaded both men to write articles for the Northern Star. Excited by the Continental Revolutions of 1848, George Julian Harney travelled to Paris in March, 1848 to meet members of the Provisional Government.

Harney was now a socialist and he used the Northern Star to promote this philosophy. Feargus O'Connor disagreed with socialism and he pressurized Harney into resigning as editor of the paper. Harney now formed his own newspaper, the Red Republican. With the help of his friend, Ernest Jones, Harney attempted to use his paper to educate his working class readers about socialism and internationalism. Harney also attempted to convert the trade union movement to socialism.

R. G. Gammage commented: "George Julian Harney's talent was best displayed when he wielded the pen; as a speaker he never came up to the standard of third class orators. The more knowing politicians adjudged him to be a spy, but there was no ground for such a supposition. Many a young man of inflexible honesty has been as foolish in his day as was George Julian Harney. Harney appeared to think that nothing but the most extreme measures were of the slightest value. He was for moving towards the object by the speediest means, and he seldom, if ever, stopped to calculate the cost. It might serve very well for men who wanted a reputation for bravery to deal out high sounding phrases about death, glory, and the like; but no body of men have the right to organise an insurrection in a country, unless fully satisfied that the people are so prepared as to hold victory in their very grasp; and a conviction of such preparedness should be founded on better evidence than their attendance at public meetings, and cheering in the moment of excitement the most violent and inflammatory orator."

In 1850 the Red Republican published the first English translation of The Communist Manifesto. The Red Republican was not a financial success and was closed down in December, 1850. Harney followed it with the Friend of the People (December 1850 - April 1852), Star of Freedom (April 1852 - December 1852) and The Vanguard (January 1853 - March 1853).

After The Vanguard ceased publication Harney moved to Newcastle and worked for Joseph Cowen's newspaper, the Northern Tribune and after travelling to meet French socialists living in exile in Jersey, Harney became editor of the Jersey Independent. Harney's support for the North in the American Civil War upset Joseph Cowen and in November 1862 was forced to resign.

In May 1863 Harney emigrated to the United States. For the next fourteen years he worked as a clerk in the Massachusetts State House. After his retirement he returned to England where he wrote a weekly column for the Newcastle Chronicle. George Julian Harney died on 9th December, 1897.

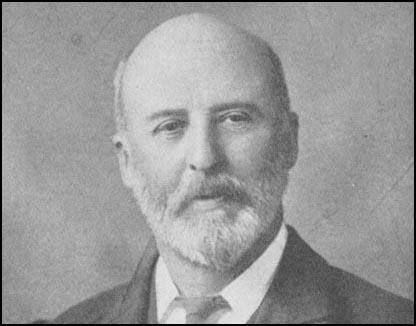

On this day in 1850 educationalist Dennis Hird, the second of five sons, was born in Ashby, Lincolnshire, on 28th January 1850. His father, Robert Hird, was a grocer, and was a devout Primitive Methodist. This religious group were sympathetic to the needs of the working-classes and were important in the development of the early trade union movement.

Hird graduated from Oxford University in 1875 and was appointed as a tutor and lecturer to students at the university who were not attached to individual colleges. In December 1884, Hird was ordained as a Church of England deacon and appointed to St Michael and All Angels Church in Bournemouth. The following year he was appointed curate of Christ Church in Battersea, where he served one of the poorest districts in London. "In this position he worked strenuously for the poor and the outcast, raising many thousands of pounds for the distressed."

In 1887 Hird was appointed as General Secretary of the Church of England Temperance Society in London. However, the authorities became concerned when in 1893 he joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and began arguing for the improvements in the education of the working class. The Bishop of London, Frederick Temple, wrote: "Mr Hird must either quit them or quit us." In the Bishop's view socialism would destroy the liberty of the individual and when Hird refused to leave the SDF he was dismissed from his post.

Dennis Hird was also part of the Christian Socialist movement that played an important role in the development of the labour movement. Other supporters included Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, Ben Tillett, Tom Mann, Katharine Glasier, Margaret McMillan and Rachel McMillan. The church authorities decided to get him out of London and Lady Isabella Somerset, agreed to help by appointing him rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor.

In January 1895 Dennis Hird gave a talk about "Jesus the Socialist" that caused a great scandal. "The agricultural laborer has given religion up, the artisan does not want it, the city business man has no time for it, and the rich? well, they are happy enough without it. Now, in face of these facts, does it not strike you as strange that the Son of God should come to the world and not be able to discover a form of government or a religion which could heal the world? But before you condemn Him, be sure that you know what the religion of Jesus is, and be sure that it has been tried."

Hird also wrote a novel in the style of Jonathan Swift, "a biting satire on England" entitled Toddle Island: Being the Diary of Lord Bottsford. This was followed by another novel, A Christian with Two Wives (1896), a humourous account of those "who believed in the infallibility of the Bible from cover to cover". Lady Somerset now decided that "her unruly rector must go" and he was dismissed. Hird now had to sell his library to provide support for his family.

In February, 1899 Charles A. Beard and Walter Vrooman established Ruskin Hall (later known as Ruskin College), a free university offering evening and correspondence courses for working class people. The two men received most of their funds from their two wealthy wives, Mary Beard and Amne Vrooman. It was named after the essayist John Ruskin (1819–1900), who had written extensively about adult education. The idea was that "economics and sociology should be taught from the working-class point of view, although not to the exclusion of the official capitalist standpoint, if that was thought desirable".

Ruskin Hall was also called a "College of the People" and the "Workman’s University". It was to be a residential institution providing study opportunities for a whole year or for shorter periods as appropriate. The residential element of the College’s work in its early years was open to men only. Harold Pollins pointed out: "It was to be part of a nationwide movement in order to cater for the large number who wanted to study but would not be able to take time off work. Provision for them, women as well as men, would be in two parts: correspondence courses, and extension classes in their own localities taught by the Ruskin Hall Faculty and by other lecturers."

Walter Vrooman, who admired the way Dennis Hird had sacrificed his career in order to defend his socialist beliefs, decided to appoint him as the the college's first principal. By the end of the year the college had fifty-five students. Janet Vaux has argued that "Ruskin... was conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power."

The students, almost all of them sent on trade union scholarships worth £52. Some of the early students included Edward Traynor (a Yorkshire miner who had lost a leg in a accident at work), Robert Carruthers (a former railway booking clerk and a soldier in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers), Frank Merry (a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and secretary to Walter Vrooman), Joseph Heywood (an apprentice journalist on the Manchester Guardian) and Horace J Hawkins (a member of the Social Democratic Federation who was expelled from the college in November, 1899). The students were expected to carry out nearly all of the domestic duties, the cooking, serving, washing up the duties and the general cleanliness.

Charles A. Beard and Walter Vrooman established a Council to run Ruskin College. It consisted mainly of university men, whom he thought in sympathy with the ideals he set for the educational work on the institution. Three trade unionists, Richard Bell, General Secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, David Shackleton, the leader of the Weavers' Union and General Secretary of the London Society of Compositors, Charles W. Bowerman, also served on the Council.

At the college Dennis Hird taught sociology, organic evolution and formal logic. This meant that Hird was teaching sociology to his students at Ruskin College nearly 50 years before it was officially recognised by the University of Oxford. During these sessions he introduced his students to the work of Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer and Émile Durkheim.

Hird also published a book explaining and popularising the theory of evolution, The Picture Book of Evolution (1906). He argued that the publishing of Darwin's book, The Origin of Species (1859) was "one of the greatest events in the history of mankind, for it has altered the thoughts of the world and killed many errors". Hird goes on to say that "with regard to living things - plants and animals - Evolution teaches that they all have come by descent from small early forms which were so simple and tiny that no one can say whether they were plants or animals."

Dennis Hird was especially interested in promoting the work of the sociologist, Frank Lester Ward, a supporter of female and racial equality, who argued that poverty could be minimized or eliminated by the systematic intervention of the government. His work was very controversial and was banned in several countries, including Russia. Although his lectures on Ward was popular with the students they upset senior figures at Oxford University. One academic commented that before "Frank Lester Ward could begin to formulate that science of society which he hoped would inaugurate an era of such progress as the world had not yet seen, he had to destroy the superstitions that still held domain over the mind of his generation. Of these, laissez-faire was the most stupefying, and it was on the doctrine of laissez-faire that he trained his heaviest guns."

Hird's teaching had a major impact on the students: "Dennis Hird was the only member of the resident lecture staff who could, and did, help us to gain some scientific knowledge about the world and man's place in it. Most of us, before we came to Ruskin, accepted the theory of evolution, the descent of man from the animal world, although it was a viewpoint still shared by only a minority of the British people, and only by a few in the academic life of Oxford. Hird greatly enriched our knowledge of the work of the great biologist Darwin, and his scientific theory of the origin of species.... The next problem we had to consider was how the different species of social organisation had arisen and changed in the human struggle for existence. We found the answer to that question in the works of a contemporary of Charles Darwin, the great German sociologist, Karl Marx.... It would have been difficult to express adequately in words the glowing feeling of an immense liberation kindled in our minds by those new views of man and his work. It was almost as if we had discovered a new world, although actually it was the discovery of the old world in the new light of a rich and revealing knowledge."

In addition to Hird, three other lecturers were appointed by Walter Vrooman. Hastings Lees-Smith, who also served as vice-principal, Bertram Wilson, who became general secretary of the college, and Alfred Hacking, a friend and supporter of Hird, who was placed in charge of the correspondence students. The students, almost all of them sent on trade union scholarships worth £52.

Hastings Lees-Smith disagreed with the politics of Hird. He was educated for an army career, first at the Aldenham School and then at the Royal Military Academy, but as a result of "a weak constitution" he left to join Queen's College. In 1899 he graduated with second-class honours in history. A member of the Liberal Party he taught economics and as he was a supporter of the free-market he upset the socialist students at Ruskin.

After two years Amne Vrooman, who had divorced her husband, stopped funding Ruskin College. The general secretary of the college, was forced to seek donations from private individuals. Bertram Wilson, General Secretary of Ruskin College sent out letters explaining why they needed donations: "Madam, I hope I am doing right in bringing Ruskin College to your notice. It was founded eight years ago with the object of giving workingmen a sound practical knowledge of subjects which concern them as citizens, thus enabling them to view social questions sanely and without unworthy class bias."

Most of the people who provided the funding of the college did not share the political beliefs of Hird. Janet Vaux has argued that "Ruskin... was conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power."

The students became increasingly disturbed by the economic teaching of Hastings Lees-Smith. At the time the Miners' Federation of Great Britain were attempting to negotiate with the Coal Owners Association a minimum wage for its members. Lees-Smith used his lectures to condemn this strategy on the grounds that it would cause unemployment and reduced investment. Sidney Webb, the Labour Party politician, advocating the minimum wage, was accused of telling "a tissue of lies".

One of the students, J. M. K. MacLachlan, a member of the Independent Labour Party, wrote an article for the September edition of Young Oxford: "The present policy of Ruskin College is that of a benevolent trader sailing under a privateer flag. Professing the aims dear to all socialists, she disavows those very principles by repudiating socialism. Let Ruskin College proclaim socialism; let her convert her name from a form of contempt into a canon of respect."

Noah Ablett, a member of the South Wales Miners' Federation, began a course at Ruskin College in 1907. He was completely self-educated and after reading the works of Karl Marx, Daniel De Leon and Tom Mann, he was a committed socialist. According to his biographer, Hywel Francis, "he quickly made his mark on educational thinking at Ruskin, and organized classes in Marxian economics and history as an alternative to the traditional liberal curriculum".

Bernard Jennings argues that Ablett had a considerable influence over the students at Ruskin: "Tensions began to build as increasing numbers of students became ardent socialists. They enjoyed Hird's lectures on sociology, a major element of which was the study of evolution, on which he had written a popular book. They disliked Lees Smith's lectures on economics, although acknowledging his ability as a teacher, because his adherence to current free-market theories was just as dogmatic as that of the left-wing students to Marxism."

In 1907 Hastings Lees-Smith, who was later to become a Liberal Party MP, was appointed professor of economics at University College, but he did not relax his grip on Ruskin. He became chairman of Ruskin College's executive committee and was chief adviser on studies. He now had control over staff recruitment and appointed, Charles Stanley Buxton, aged 23 as vice-principal. His father was Charles Sydney Buxton, the President of the Board of Trade.

Lees-Smith also recruited Henry Sanderson Furniss to lecture on economics, who both shared his view "of the relationship between class improvement and education". Sanderson Furniss came to realise that he and Buxton were intended to carry on Lees Smith's campaign against Hird: "They were, however, ill-equipped to do so, or to provide an antidote to the Marxist ideas which Furniss criticised without knowing much about them. They knew little about teaching, and less about working-class life."

Although Dennis Hird was the Principal of Ruskin College, he was not consulted on these appointments. On his appointment his duties were defined as "to be in charge at Ruskin Hall". However, this was later changed to say all decisions were to be made by a House Committee of three, consisting of the Principal, the Vice-Principal and the General Secretary of the College. Buxton and Sanderson Furniss now joined forces to constantly outvote Hird.

Dennis Hird remained one of the leaders of the Christian Socialist movement. In 1908 he published a pamphlet, Jesus the Socialist, that was based on the speech he delivered in 1896, that resulted in him losing his post as rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor. The pamphlet sold over 70,000 copies.

Hirds begins the pamphlet with a quote from Henry Hart Milman, the former Dean of St. Paul's: "Christianity has been tried for more than eighteen hundred years: perhaps it is time to try the religion of Jesus.” Hird comments: "That is a pressing question. Is Christianity, as now usually practised and taught, the same thing as the religion of Jesus? I maintain emphatically that it is not!"

Hird admitted that one of his concerns was that the poor appeared to be rejecting Christianity. His answer to this problem was to show them that Jesus advocated socialism. "Was Jesus a Socialist? It is true He was never called a Socialist; it is also true He was never called a Methodist, or a Baptist, or a Papist, or a Church of England man; thank God, He was called by none of these names. It is true He never saw a Socialist; it is also true that He never saw a bishop or a pope."

Hird then went on to look at the teachings of the son of God. "Jesus said: 'Thou shall love thy neighbor as thyself' (Matthew 19:19 and 22:39). I know no definition of Socialism to equal this 'Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.' You are familiar with this quotation which Jesus made from (Leviticus 19:18), so familiar with it that perhaps you have thought it was an original utterance by Jesus. We must remember the method employed by Jesus. He gave us no system of thought, no creed, no cut-and-dried dogmas, no church organizations: He unfolded great principles, and many of those were not new, but were set forth with new vigor and forcible illustrations."

Dennis Hird attempted to explain why the Church had not stayed true to the teachings of Jesus: "It is so much easier to worship Christ than to imitate Jesus, that men have taken up the worship, and I think some of them verily believe, when they confess their sins by the aid of a choir, or sing their hymns in fairly good harmony, that God is pleased with the sweet music. Jesus sought men to imitate him rather than to worship Him.... That is a very different thing from listening to a choral service on a Sunday morning, and giving a small check to the curate fund. Jesus seeks imitation, not adulation. A far-away heaven, with a far-away God, enveloped in a far-away glory, is no use to this world, and certainly is no part of the teaching of Jesus."

Noah Ablett, the most left-wing of Ruskin's students, set up Marxist tutorial classes in the central valleys of the Welsh coalfield. In October 1908, Ablett and some of his followers established the Plebs League, an organisation committed to the idea of promoting left-wing education amongst workers. The objective of the Plebs League was "to bring about a definite and more satisfactory connection between Ruskin College and the Labour Movement".

Membership of the organisation was open to all resident and correspondence students, past and present, on the payment of 1s. per year. Over the next few weeks branches were established in five towns in the Welsh coalfield. Arthur J. Cook and William H. Mainwaring were two early recruits to these classes. Ablett was described as "a remarkable young man, a rebel of cosmopolitan, perhaps cosmic, importance" and "as an educator and ideologue, he was unique".

In November 1908, Oxford University announced that it was going to take over Ruskin College. The chancellor of the university, George Curzon, was the former Conservative Party MP and the Viceroy of India. His reactionary views were well-known and was the leader of the campaign to prevent women having the vote. Curzon visited the college where he made a speech to the students explaining the decision.

Dennis Hird replied to Curzon: "My Lord, when you speak of Ruskin College you are not referring merely to this institution here in Oxford, for this is only a branch of a great democratic movement that has its roots all over the country. To ask Ruskin College to come into closer contact with the University is to ask the great democracy whose foundation is the Labour Movement, a democracy that in the near future will come into its own, and, when it does, will bring great changes in its wake".

The author of The Burning Question of Education (1909) reported: "As he concluded, the burst of applause that emanated from the students seemed to herald the dawn of the day Dennis Hird had predicted. Without another word, Lord Curzon turned on his heel and walked out, followed by the remainder of the lecture staff, who looked far from pleased. When the report of the meeting was published in the press, the students noted that significantly enough Dennis Hird's reply was suppressed, and a few colourless remarks substituted."

William Craik, a member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (later the National Union of Railwaymen) pointed out that his fellow students were "very perturbed at the direction in which the teaching and control of the College was moving, and by the failure of the trade union leaders to make any effort to change that direction. We new arrivals had little or no knowledge of what had been taking place at Ruskin before we got there. Most of us were socialists of one party shade or other."

Noah Ablett emerged as the leader of the resistance to the plans of Hastings Lees-Smith. A coalminer from South Wales, he was one of the Ruskin students who was greatly influenced by the teachings of Dennis Hird. He set up Marxist tutorial classes in the central valleys of the Welsh coalfield. In January 1909, Ablett and some of his followers established the Plebs League, an organisation committed to the idea of promoting left-wing education amongst workers. Over the next few weeks branches were established in five towns in the coalfield. Arthur J. Cook and William H. Mainwaring were two early recruits to these classes. Ablett was described as "a remarkable young man, a rebel of cosmopolitan, perhaps cosmic, importance" and "as an educator and ideologue, he was unique".

Students of Ruskin College were forbidden to speak in public without the permission of the executive committee. In an effort to marginalise Dennis Hird, new rules such as the requirement for regular essays and quarterly revision papers were introduced. "This met with strong resistance from the majority of the students, who looked upon it as one more way of making the connection with the University still closer... Most of the students had come to Ruskin College on the understanding that there would be no tests other than monthly essays set and examined by their respective tutors, and afterwards discussed in personal interviews with them."

In August 1908, Charles Stanley Buxton, the vice-principal of Ruskin College, published an article in the Cornhill Magazine. He wrote that "the necessary common bond is education in citizenship, and it is this which Ruskin College tries to give - conscious that it is only a new patch on an old garment." (38) It has been argued that "it read as if it had been written by someone who looked upon the workers as a kind of new barbarians whom he and his like had been called upon to tame and civilise". The students were not convinced by this approach as Dennis Hird had told them about the quotation of Karl Marx: "The more the ruling class succeeds in assimilating members of the ruled class the more formidable and dangerous is its rule."

Lord George Curzon published Principles and Methods of University Reform in 1909. In the book he pointed out that it was vitally important to control the education of future leaders of the labour movement. He urged universities to promote the growth of an elite leadership and rejected the 19th century educational reformers call for reform on utilitarian lines to encourage "upward movement" of the capitalist middle class: "We must strive to attract the best, for they will be the leaders of the upward movement... and it is of great importance that their early training should be conducted on liberal rather than on utilitarian lines."

In February, 1909, Dennis Hird was investigated in order to discover if he had "deliberately identified the college with socialism". The sub-committee reported back that Hird was not guilty of this offence but did criticise Henry Sanderson Furniss for "bias and ignorance" and recommended the appointment of another lecturer in economics, more familiar with working class views. Hastings Lees-Smith and the executive committee rejected this suggestion and in March decided to dismiss Hird for "failing to maintain discipline". He was given six months' salary (£180) in lieu of notice, plus a pension of £150 a year for life.

It is believed that 20 students were members of the Plebs League. Its leader, Noah Ablett organised a students' strike in support of Hird. Another important figure was George Sims, a carpenter, who had been sponsored by Albert Salter, a doctor working in Bermondsey who was also a member of the Independent Labour Party. He was the man chosen to deal with the press.

The Daily News reported: "It is one of the quaintest of strikes, this revolt of the 54 students of Ruskin College against what they consider the intolerable action of the authorities with regard to Mr. Dennis Hird, the Principal." In an interview with one of the strikers, George Sims claimed that the students had been told by the authorities that Hird had been sacked because he had been "unable to maintain discipline". The real reason was the way that Hird had been teaching sociology.

On 2nd April the newspaper carried an interview with Dennis Hird: "I have received hundreds of letters of sympathy from past students....There can be no foundation of any sort, technical or otherwise, for the statement that I have failed to maintain discipline. The fact that I have the love of hundreds of students, past and present, and that they would do anything for me, is surely the answer to that." The journalist added "the workingmen students of Ruskin College were as determined as ever that under no circumstances would they consent to Mr. Hird's going.... As matters stand at present it is clear that only the reinstatement of Mr. Hird can save serious trouble."

The following day the newspaper carried an editorial on the dispute: "We are far from wishing to take any side in the controversy, but the unanimity of the students in their support of Mr. Hird, the dismissed Principal, is a fact which cannot be ignored. It may be that the students are mistaken as to the reason for his dismissal, but there is no doubt of the genuine affection they have for their Principal and the reality of their conviction that his dismissal is associated with an organic change in regard to the College.... Ruskin College is an effort to permeate the working classes with ideals and culture, which, while elevating and benefiting the students, will not divorce them from their own atmosphere but will serve to make that atmosphere purer and better."

The Ruskin authorities decided to close the college for a fortnight and then re-admit only students who would sign an undertaking to observe the rules. Of the 54 students at Ruskin College at that time, 44 of them agreed to sign the document. However, the students decided that they would use the Plebs League and its journal, the Plebs' Magazine, to campaign for the setting up of a new and real Labour College.

Dennis Hird received very little support from other advocates of working-class education. Albert Mansbridge, the

founder of the Workers' Educational Association (WEA) in 1903, blamed Hird's preaching of socialism for his dismissal. In a letter to a French friend, he wrote "the low-down practice of Dennis Hird in playing upon the class consciousness of swollen-headed students embittered by the gorgeous panorama ever before them of an Oxford in which they have no part."

Noah Ablett took the lead in establishing an alternative to Ruskin College. He saw the need for a residential college as a cadre training school for the labour movement that was based on socialist values. George Sims, who had been expelled after his involvement in the Ruskin strike, played an important role in raising the funds for the project. On 2nd August, 1909, Ablett and Sims organised a conference that was attended by 200 trade union representatives. Dennis Hird, Walter Vrooman and Frank Lester Ward were all at the conference.

Sims explained that the "last link which bound Ruskin College to the Labour Movement had been broken, the majority of the students had taken the bold step of trying to found a new college owned and controlled by the organised Labour Movement." Ablett moved the resolution: "That this Conference of workers declares that the time has now arrived when the working class should enter the educational world to work out its own problems for itself."

The conference agreed to establish the Central Labour College (CLC). The students rented two houses in Bradmore Road in Oxford. It was decided that "two-thirds of representation on Board of Management shall be Labour organisations on the same lines as the Labour Party constitution, namely, Trade Unions, Socialist societies and Co-operative societies." Most of the original funding came from the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF) and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR).

Dennis Hird agreed to act as Principal and to lecture on sociology and other subjects, without any salary. George Sims worked as its secretary and Alfred Hacking was employed as tutor in English grammar and literature. Fred Charles accepted a post as tutor in industrial and political history. The teaching staff was supplemented by regular visiting lecturers, such as Frank Horrabin, Winifred Batho, Rebecca West, Emily Wilding Davison, H. N. Brailsford, Arthur Horner and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. In 1910 William Craik was appointed as Vice-Principal.

In 1911 the college moved to London. "Very soon after the College arrived in Kensington it began to conduct evening classes, both within and without, for the working men and women in the district, and to extend their range. Not many years were to pass before there was hardly a suburb in Greater London without one or more Labour College classes at work in it. Nothing like this, needless to say, would have been possible had the College remained in Oxford."

John Saville has argued that the Central Labour College provided the kind of socialist education that was not provided by Ruskin College and the Workers' Educational Association. "What we have in these years is both the attempt to channel working-class education into the safe and liberal outlets of the Workers' Educational Association and Ruskin College, and the development of working-class initiatives from below; and it is the latter only which made its contribution to the socialist movement - and a considerable contribution it was."

Bernard Jennings agrees with Saville on this point and points out that Richard Tawney, A. D. Lindsay and Archbishop William Temple were all supporters of Ruskin College and the WEA over the Central Labour College: "There is no doubt that the establishment preferred the WEA and Ruskin to the Labour college movement, a fact exploited quite brazenly by the WEA in the 1920s. Temple, Tawney and A. D. Lindsay all warned the Board of Education and the LEAs that unless they supported the WEA and respected its academic freedom, workers' education would fall to the CLC."

The Central Labour College was always short of money. The Plebs Magazine was used to raise funds. "Your cash will be used to good purpose - make no doubt of that. The CLC flag has been kept flying up to now by the pluck, devotion and enthusiasm of the garrison. Only those, perhaps, who - like the present writer - have had an occasional glimpse behind the scenes, know the extent of the devotion and that enthusiasm. What are you going to do about it?"

Dennis Hird suffered for many years with thrombosis. He became very ill in 1913 and was confined to his bed for over a year. He returned to work in 1914 but in May 1915 he was forced back to his bed. William Craik and George Sims took over most of his details. However, Craik and Sims were conscripted into the British Army in 1917 and it was forced to close until the end of the First World War.

One of Hird's former students visited him in 1919 and "despite the tediousness of his prolonged confinement in bed, he was cheerful and quite hopeful of being able to return to his post." Unfortunately he did not recover and died on 13th July 1920. William Craik replaced him as Principal of the Central Labour College.

On this day in 1870 Ada Nield, the second child in a family of thirteen of William Nield, brickmaker, and his wife, Jane Hammond Nield was born in Audley, Staffordshire. Ada was taken from school at the age of eleven to help look after the family, especially her younger sister May, who was an epileptic.

As the authors of One Hand Tied Behind Us (1978) have pointed out: "She had to leave school at eleven and take on the heavy responsibility of looking after her seven younger brothers, combining this with various odd jobs. Her father, a poor farmer, had to give up his farm for lack of capital, and moved his family to Crewe where he could more easily find another job."

In 1887 the Nield family moved to Crewe, and Ada worked at a shop in Nantwich. Later she found employment in the Compton Brothers clothing factory. In 1894 she published anonymously in The Crewe Chronicle, a series of letters describing conditions in her factory. As her biographer, David Doughan, pointed out: "These letters were circumstantially critical of the pay and conditions of factory women, especially compared to those of their male colleagues doing the same work. This resulted in Ada losing her position"

Ada Nield now joined the Independent Labour Party and soon afterwards the local branch stated: "It has been agreed at ILP meetings that the rights of women workers must be recognized, that common cause must be made with these our sisters, and that something definite must be done sooner or later - and the sooner the better." Ada, now a committed socialist, was also elected to the Nantwich Board of Guardians. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "In 1896 she spent several weeks travelling around the north-east in the Clarion van, holding meetings to publicize the policies of the ILP." Ada was also a regular contributor to The Clarion and The Labour Leader. One biographer has commented that Ada "was very diffident about her personal appearance, but contemporaries record that she was very good-looking, with striking red hair."

In 1897 Ada Nield married George Chew, an ILP organizer. The following year, her only child, a daughter, was born. The couple settled in Rochdale where they ran a small shop. In 1900 she was given a full-time post by the Women's Trade Union League and she would take Doris, her young daughter, with her on her travels. During this period she became friends with Ramsay MacDonald, Margaret MacDonald, John Bruce Glasier, Katherine Glasier, Selina Cooper, John Robert Clynes and Mary Macarthur.

Ada Nield Chew was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and was totally against the policy of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). The main objective of the WSPU was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic pointed out, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.”

On the 16th December 1904 The Clarion published a letter from Ada Nield Chew on WSPU policy: "The entire class of wealthy women would be enfranchised, that the great body of working women, married or single, would be voteless still, and that to give wealthy women a vote would mean that they, voting naturally in their own interests, would help to swamp the vote of the enlightened working man, who is trying to get Labour men into Parliament."

The following month Christabel Pankhurst replied to the points that Ada made: "Some of us are not at all so confident as is Mrs Chew of the average middle class man's anxiety to confer votes upon his female relatives." A week later Ada Nield Chew retorted that she still rejected the policies in favour of "the abolition of all existing anomalies... which would enable a man or woman to vote simply because they are man or woman, not because they are more fortunate financially than their fellow men and women". As the authors of One Hand Tied Behind Us (1978) pointed out: "The fiery exchange ran on through the spring and into March. The two women both relished confrontation, and neither was prepared to concede an inch. They had no sympathy for the other's views, and shared no common experiences that might help to bridge the chasm."

In January 1908 Ada Nield Chew and Edith New chained themselves to the railings of 10 Downing Street. According to The Daily Express: "Each suffragist wore round her waist a long, steel chain - not unlike a very heavy dog chain. Each took the loosened end of the chain, threw it round the railings, and fixed it to the rest of the chain. This was done so deftly that it was not until the police heard the click of the lock that they understood the clever move by which the suffragists had outwitted them, and prevented for a time their own removal. Votes for women! shouted the two voluntary prisoners simultaneously. Votes for Women!"

In 1911 Ada Nield Chew and Selina Cooper became organizers for the NUWSS. She was also an active member of the Fabian Women's Group and wrote for various journals including The Common Cause, The Freewoman and The Englishwoman's Review.

Ada Nield Chew influenced the NUWSS decision in April 1912 to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary by-elections. Emily Davies, a member of the Conservative Party, and Margery Corbett-Ashby, an active supporter of the Liberal Party, resigned from the NUWSS over this decision. However, others like Catherine Osler, resigned from the Women's Liberal Federation in protest against the government's attitude to the suffrage question.

The NUWSS established an Election Fighting Fund (EFF) to support these Labour candidates. The EFF Committee, which administered the fund, included Margaret Ashton, Henry N. Brailsford, Kathleen Courtney, Muriel de la Warr, Millicent Fawcett, Catherine Marshall, Isabella Ford, Laurence Housman, Margory Lees and Ethel Annakin Snowden.

On 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS, declared that it was suspending all political activity until the First World War was over. Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Fawcett refused to argue against the war. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace."

Ada Nield Chew was completely against this policy: "The militant section of the movement... would without doubt place itself in the trenches quite cheerfully, if allowed. It is now ... demanding, with all its usual pomp and circumstance of banner and procession, its share in the war. This is an entirely logical attitude and strictly in line with its attitude before the war. It always glorified the power of the primitive knock on the nose in preference to the more humane appeal to reason.... What of the others? The non-militants - so-called - though bitterly repudiating militancy for women, are as ardent in their support of militancy for men as their more consistent and logical militant sisters."

Ada Nield Chew disagreed with this policy and like Catherine Marshall, Helena Swanwick, Maude Royden, and Selina Cooper she refused on principle to undertake war work. Later she joined Mary Sheepshanks, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse and Chrystal Macmillan in becoming a member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

After the war Ada Nield Chew ceased to be active in politics. According to David Doughan: "She now concentrated on the family business, starting an independent mail-order wholesale drapery line which met with such success that by 1922 she had to rent a small warehouse. She retired from the mail-order business in 1930. Although a seasoned traveller to all parts of Britain, she had never been abroad until 1927, when she and her daughter holidayed in the south of France. This she followed with a visit to her brother in South Africa in 1932, a round-the-world tour in 1935, and motoring holidays in France and Switzerland."

Ada Nield Chew died on 27th December 1945 at 55 Ormerod Road, Burnley, Lancashire.

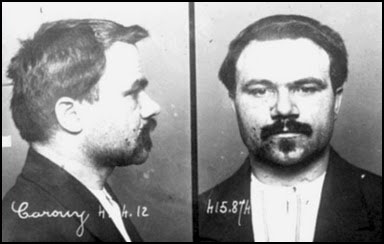

On this day in 1883 Édouard Carouy was born in Belgium. Édouard Carouy was born in Lens-sur-Deudre, Belgium. His mother died when he was three-years-old. He moved to Paris where he worked in a factory. He also associated with a group of anarchists.

Jules Bonnot arrived in the city in 1911. According to Victor Serge: "From the grapevine we gathered that Bonnot... had been traveling with him by car, had killed him, the Italian having first wounded himself fumbling with a revolver." Bonnot soon formed a gang that included local anarchists, Carouy, Raymond Callemin, Octave Garnier, René Valet, André Soudy and Stephen Monier. Serge was totally opposed to what the group intended to do. Callemin visited Serge when he heard what he had been saying: "If you don't want to disappear, be careful about condemning us. Do whatever you like! If you get in my way I'll eliminate you!" Serge replied: "You and your friends are absolutely cracked and absolutely finished."

These men shared Bonnot's illegalist philosophy that is reflected in these words: "The anarchist is in a state of legitimate defence against society. Hardly is he born than the latter crushes him under a weight of laws, which are not of his doing, having been made before him, without him, against him. Capital imposes on him two attitudes: to be a slave or to be a rebel; and when, after reflection, he chooses rebellion, preferring to die proudly, facing the enemy, instead of dying slowly of tuberculosis, deprivation and poverty, do you dare to repudiate him? If the workers have, logically, the right to take back, even by force, the wealth that is stolen from them, and to defend, even by crime, the life that some want to tear away from them, then the isolated individual must have the same rights."

Richard Parry, the author of the The Bonnot Gang (1987) has argued: "The so-called 'gang', however, had neither a name nor leaders, although it seems that Bonnot and Garnier played the principal motivating roles. They were not a close-knit criminal band in the classical style, but rather a union of egoists associated for a common purpose. Amongst comrades they were known as 'illegalists', which signified more than the simple fact that they carried out illegal acts. Illegal activity has always been part of the anarchist tradition, especially in France."

On 21st December, 1911 the gang robbed a messenger of the Société Générale Bank of 5,126 francs in broad daylight and then fled in a stolen Delaunay-Belleville car. It is claimed that they were the first to use an automobile to flee the scene of a crime. As Peter Sedgwick pointed out: "This was an astounding innovation when policemen were on foot or bicycle. Able to hide, thanks to the sympathies and traditional hospitality of other anarchists, they held off regiments of police, terrorized Paris, and grabbed headlines for half a year."

The gang then stole weapons from a gun shop in Paris. On 2nd January, 1912, they broke into the home of the wealthy Louis-Hippolyte Moreau and murdered both him and his maid. This time they stole property and money to the value of 30,000 francs. Bonnot and his men fled to Belgium, where they sold the stolen car. In an attempt to steal another they shot a Belgian policeman. On 27th February they shot two more police officers while stealing an expensive car from a garage in Place du Havre.

On 25th March, 1912, the gang stole a De Dion-Bouton car in the Sénart Forest by killing the driver. Later that day they killed two cashiers during an attack on the Société Générale Bank in Chantilly. Leading anarchists in the city were arrested. This included Victor Serge who complained in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine.... I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide."

The police offered a reward of 100,000 in an effort to capture members of the gang. This policy worked and on information provided by an anarchist writer, André Soudy was arrested at Berck-sur-Mer on 30th March. This was followed a few days later when Edouard Carouy was betrayed by the family hiding him. Raymond Callemin was captured on 7th April.

On 24th April, 1912, three policemen surprised Bonnot in the apartment of a man known to buy stolen goods. He shot at the officers, killing Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, and wounding another officer before fleeing over the rooftops. Four days later he was discovered in a house in Choisy-le-Roi. It is claimed the building was surrounded by 500 armed police officers, soldiers and firemen.

According to Victor Serge: "They caught up with him at Choisy-le-Roi, where he defended himself with a pistol and wrote, in between the shooting, a letter which absolved his comrades of complicity. He lay between two mattresses to protect himself against the final onslaught." Bonnot was able to wound three officers before the house before the police used dynamite to demolish the front of the building. In the battle that followed Bonnot was shot ten times. He was moved to the Hotel-Dieu de Paris before dying the following morning. Octave Garnier and René Valet were killed during a police siege of their suburban hideout on 15th May, 1912.

The trial of Édouard Carouy, Raymond Callemin, Victor Serge, Rirette Maitrejean, Edouard Carouy, Jean de Boe, André Soudy, Eugène Dieudonné and Stephen Monier, began on 3rd February, 1913. Victor Serge has claimed: "Edouard Carouy, who had no part in these events, was betrayed by the family hiding him and, although armed like the others, was arrested without any attempt at self-defense; this athletic young man was exceptional in being quite incapable of murder, though quite ready to kill himself."

Callemin, Soudy, Dieudonné and Monier were sentenced to death. When he heard the judge's verdict, Callemin jumped up and shouted: "Dieudonné is innocent - it's me, me that did the shooting!" Carouy was sentenced to hard labour for life. Serge received five years' solitary confinement but Maitrejean was acquitted. Dieudonné was reprieved but Callemin, Soudy and Monier were guillotined at the gates of the prison.

On 27th February, 1913, a prison warder told Serge: "Carouy is dying. Can you hear him? That's him gasping away... He took some poison that he'd got hidden in the shoes of his shoes." Édouard Carouy died later that day.

On this day in 1890 Prudence Crandall died. Crandall was born in Rhode Island on 3rd September, 1803. After being educated at a Society of Friends school in Plainfield, Connecticut, Crandall established her own private academy for girls at Canterbury.

The school was a great success until she decided to admit a black girl. When Crandall, a committed Quaker, refused to change her policy of educating black and white students together, parents began taking their children away from the school. With the support of William Lloyd Garrison and the Anti-Slavery Society, in March 1833, Crandall opened a school for black girls in Canterbury.

Local people were furious at Crandall's actions and attempts were made to prevent the school receiving essential supplies. The school continued and began to attract girls from Boston and Philadelphia. The local authorities then began using a vagrancy law against these students. These girls could now be given ten lashes of the whip for attending the school.

In 1834 Connecticut passed a law making it illegal to provide a free education for black students. When Crandall refused to obey the law she was arrested and imprisoned. Crandall was convicted but won the case on appeal. When news of the court decision reached Canterbury, a white mob attacked the school and threatened the lives of Crandall and her students. Afraid that the children would be killed or badly injured, Crandall decided to close her school down.

In September 1834 Crandall moved to Illinois where she married Calvin Philleo, a Baptist clergyman.

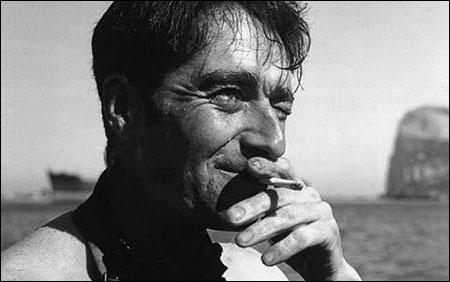

On this day in 1909 Lionel (Buster) Crabb, the son of Hugh Alexander Crabb and his wife, Beatrice Goodall, was born in Streatham, London, on 28th January 1909. His father was a commercial traveller for a firm of photographic merchants. According to his biographer, Richard Compton-Hall, "little is known about Crabby or Buster Crabb's early life save that it was modestly commercial."

Lionel Crabb earned his nickname from the Hollywood actor, athlete and pin-up Buster Crabbe, who had played Flash Gordon in the film series and won a gold medal for swimming at the 1932 Olympic Games. "In almost every way, the English Buster Crabb was entirely unlike his namesake, being English, tiny, and a poor swimmer (without flippers, he could barely complete three lengths of a swimming pool). With his long nose, bright eyes and miniature frame, he might have been an aquatic garden gnome."

He worked in a variety of jobs and eventually joined the Merchant Navy. On the outbreak of the Second World War he transferred to the Royal Navy where he was trained as a diver. In 1940 he volunteered for bomb disposal duties. In 1942 he was sent to Gibraltar, to take part in the underwater battle around the Rock, where Italian frogmen, using rnanned torpedoes and limpet mines, were sinking thousands of tons of Allied shipping. Crabb and his fellow divers set out to stop them, with remarkable success, blowing up enemy divers with depth charges, intercepting torpedoes and peeling mines off the hulls of ships. "Despite his nickname, Commander Lionel Kenneth ("Buster") Crabb was no great shakes as a surface swimmer; but given a pair of rubber flippers, some goggles and an oxygen tank, he was at home in the murky depths. In 1942 when Italian divers were busily attaching lethal limpet mines to the bottoms of Royal Navy ships at anchor off Gibraltar, Buster Crabb was even busier at the far more dangerous job of removing them." Nicholas Elliott worked with Crabb during the war, and considered him "a most engaging man of the highest integrity... as well as being the best frogman in the country, probably in the world".

In 1945 Crabb cleared mines from the ports of Venice and Livorno, and when the militant Zionist group Irgun began attacking British ships with underwater explosives, he was called in to defuse them. This was an extremely dangerous job, but Crabb survived and in 1947 awarded the George Medal for "undaunted devotion to duty" and the OBE. Crabb also investigated a suitable discharge site for a pipe from the atomic weapons station at Aldermaston. Crabbe later returned to the Royal Navy and after helping rescue men trapped in a submarine, and was promoted to the rank of commander in 1952. Buster Crabb married Margaret Elaine on 15th March 1952. The couple separated in 1953.

In March 1955 Buster Crabb was forced to leave the navy on age grounds. According to Ben Macintyre: "He cut a remarkable figure in civilian life, wearing beige tweeds, a monocle and a pork pie hat, and carrying a Spanish swordstick with a silver knob carved into the shape of a crab. But there was another, darker side... Crabb suffered from deep depressions, and had a weakness for gambling, alcohol and barmaids. When taking a woman out to dinner he liked to dress up in his frogman outfit; unsurprisingly, this seldom had the desired effect, and his emotional life was a mess. In 1956 he was in the process of getting divorced after a marriage that had lasted only a few months. He worked, variously, as a model, undertaker and art salesman, but like many men who had seen vivid wartime action, he found peace a pallid disappointment.

In April 1956, the Soviet leaders, Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin paid a visit on the battleship Ordzhonikidz, docking at Portsmouth. The visit was designed to improve Anglo-Soviet relations. Sir Anthony Eden, the prime minister, who had high hopes of establishing better relations and moderating the Cold War issued a precise directive to all services banning any intelligence operation of any kind against the Soviet leaders and the ship.

The MI6 London station - run by Nicholas Elliott - decided that the visit was too good an opportunity to miss and ten days beforehand put up a list of six operations to MI6's Foreign Office adviser. "The Admiralty had been particularly keen to understand the underwater-noise characteristics of the Soviet vessels. The placing of a Foreign Office adviser inside MI6 was part of a drive to put the service on a somewhat tighter leash, but when an MI6 officer ambled into his office for a ten-minute chat about the plans, the adviser came away thinking they would then be cleared at a higher level (as some sensitive operations were) while Elliott and his colleagues assumed that the quick conversation constituted clearance." When Eden heard about it he told MI6: "I am sorry, but we cannot do anything of this kind on this occasion." Elliott would later insist that the "operation was mounted after receiving a written assurance of the Navy's interest and in the firm belief that government clearance had been given". Elliott also argued: "We don't have a chain of command. We work like a club."

MI5 decided to bug the rooms at Claridge's Hotel that had been taken over by the Soviet delegation. The operation was a failure: "We listened to Khrushchev for hours at a time, hoping for pearls to drop. But there were no clues to the last days of Stalin, or to the fate of the KGB henchman Beria. Instead, there were long monologues from Khrushchev addressed to his valet on the subject of his attire. He was an extraordinary vain man. He stood in front of the mirror preening himself four hours at a time, and fussing with his hair parting."

On 16th April 1956, the day before the cruiser was due to arrive, Crabb and Bernard Smith, his MI6 minder, arrived in Portsmouth and registered with a local hotel. Against the rules of the SIS both men signed in their real names. Contrary to the fundamental rules of diving, that evening Crabb drank at least five double whiskys. By daybreak, the toxicity in his blood remained fatally high.

The following morning Crabb dived into Portsmouth Harbour. "The main task was to swim underneath the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, explore and photograph her keel, propellers and rudder, and then return. It would be a long, cold swim, alone, in extremely cold and dirty water, with almost zero visibility at a depth of about thirty feet. The job might have daunted a much younger and healthier man. For a forty seven-year-old, unfit, chain-smoking depressive, who had been extremely drunk a few hours earlier, it was close to suicidal." However, Elliott insisted that "Crabb was still the most experienced frogman in England, and totally trustworthy ... He begged to do the job for patriotic as well as personal motives." Peter Wright, who worked for MI5 said that it was a typical piece of MI6 adventurism, ill-conceived and badly executed."

Gordon Corera, the author of The Art of Betrayal (2011) has pointed out: "Where Bond battled the bad guys in the crystal-clear Caribbean, the diminutive Crabb plunged into the cold, muddy tide of Portsmouth Harbour just before seven in the morning. He had about ninety minutes of air and by 9.15 it was clear something had gone wrong. For a while, it looked like the whole affair might be hushed up. The MI6 officer went back to the hotel to rip out the registration page. The hotel owner went to the press, who sniffed a good story. The disappearance of a well-known hero could not be covered up."

That night, James Thomas, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was dining with some of the Soviet visitors, one of whom asked, "What was that frogman doing off our bows this morning". According to the Russian, Crabb had been seen swimming at the surface at 7.30 a.m. by a Soviet sailor. The commander-in-chief Portsmouth, denying knowledge of any frogman, assured the Russian there would be an Inquiry and hoped that all discussion had been terminated. With the help of the intelligence services, the Admiralty attempted to cover up the attempt to spy on the Russian ship. On 29th April the Admiralty announced that Crabb went missing after taking part in trials of underwater apparatus in Stokes Bay (a place five kilometres from Portsmouth).

The Soviet government now issued a statement announcing that a frogman was seen near the cruiser Ordzhonikidze on 19th April. This resulted in newspapers publishing stories claiming that Crabb had been captured and taken to the Soviet Union. Time Magazine reported: "... soon after anchoring, the Ordzhonikidze had taken the precaution of putting a crew of its own frogmen over the side. Had the Russian frogmen met their British counterpart in the quiet deep? Had Buster Crabb been killed then and there, or kidnapped and carried off to Russia? At week's end, the mystery of Frogman Crabb's fate remained as deep and impenetrable as the waters that surrounded so much of his life." Nicholas Elliott claimed that he knew how Crabb died: "He almost certainly died of respiratory trouble, being a heavy smoker and not in the best of health, or conceivably because some fault had developed in his equipment."

Sir Anthony Eden, the British prime minister was furious when he discovered about the MI6 operation that had taken place without his permission. Eden pointed out in the House of Commons: "I think it is necessary, in the special circumstances of this case, to make it clear that what was done was done without the authority or knowledge of Her Majesty's Ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken." Ten days later, Eden made another statement making it clear that his explicit instructions had been disobeyed.

Eden forced the Diretor-General of MI6, Major-General John Sinclair, to take early retirement. He was replaced by Sir Dick White, the head of MI5. As MI5 was considered by MI6 to be an inferior intelligence service, this was the severest punishment that could be inflicted on the organization. George Kennedy Young, a senior figure in MI6 defended the actions of Elliott. He argued that in "a world of increasing lawlessness, cruelty and corruption... it is the spy who has been called upon to remedy the situation created by the deficiencies of ministers, diplomats, generals and priests.. these days the spy finds himself the main guardian of intellectual integrity."

On 9th June 1957, a headless body in a frogman suit was discovered floating off Pilsey Island. As the hands were also missing it was impossible to identify it as being that of Lionel Crabb. His former wife inspected the body and was unsure if it was Crabb. Pat Rose, his girlfriend, claimed it was not him but another friend, Sydney Knowles, said that Crabb, like the dead body, had a scar on the left knee. The coroner recorded an open verdict but announced that he was satisfied the remains were those of Crabb.

In 1960 J. Bernard Hutton published his book Frogman Spy. Hutton argues that his sources claim that Crabb had been captured alive during his espionage activities and had been smuggled back to Soviet Union for torture and interrogation. According to Russian documents that Hutton had seen, Crabb later served as a diving officer in the Russian Navy. To help conceal the fate of Crabb, the Soviets dropped a headless and handless body wearing Crabb's equipment in the water near where he was lost a year earlier.

Tim Binding wrote a fictionalized account of Crabb's life, Man Overboard. Published in 2005, Binding novel is based on the story that appeared in Frogman Spy. Soon afterwards Binding was contacted by Sydney Knowles, the man who had originally identified Crabb's body. Knowles told Binding that Crabb was murdered by MI5 when it was discovered that he intended to defect to the Soviet Union. According to Knowles, Crabb was instructed to carry out a spying operation on the Ordzhonikidze. Crabb was supplied with a new diving partner who killed him during the mission. Knowles alleges that he was ordered by MI5 to identify the body, when he knew it was definitely not Crabb. Binding published this information in an article in The Mail on Sunday on 26th March, 2006.

In November, 2007, Eduard Koltsov, a former Soviet frogman, gave an interview where he claimed that he killed Crabb. It was argued that a tip-off from a British spy (probably Kim Philby) meant that he had been lying in wait. According to Gordon Corera, the author of The Art of Betrayal (2011): "Fearing that Crabb was planting a mine to blow up the ship, the frogman says he swam up from below to slash Crabb's air tubes and then his throat with a knife. The body was so small he at first thought it belonged to a boy. But he then found himself staring into the dying eyes of a middle-aged man. According to his unconfirmed account, he pushed the body away into the undercurrents, leaving a trail of blood."

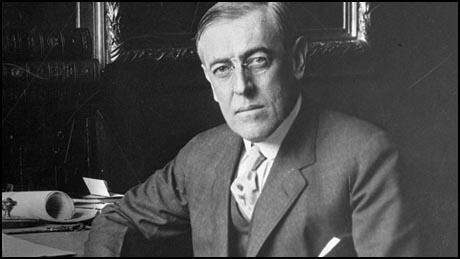

On this day in 1915 President Woodrow Wilson objects to the political and literacy clauses in the proposed Immigration Act. Wilson said: " The 1917 Immigration Act increased the entry head tax to $8. People who were now excluded from the United States included: "all idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded persons, epileptics, insane persons; persons who have had one or more attacks of insanity at any time previously; persons of constitutional psychopathic inferiority; persons with chronic alcoholism; paupers; professional beggars; vagrants; persons afflicted with tuberculosis in any form or with a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease; persons not comprehended within any of the foregoing excluded classes who are found to be and are certified by the examining surgeon as being mentally or physically defective, such physical defect being of a nature which may affect the ability of such alien to earn a living; persons who have been convicted of or admit having committed a felony or other crime or misdemeanor involving moral turpitude; polygamists, or persons who practice polygamy or believe in or advocate the practice of polygamy; anarchists, or persons who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States"."

The most controversial aspect to the act was the proposal to exclude all "aliens over sixteen years of age, physically capable of reading, who cannot read the English language, or some other language or dialect, including Hebrew or Yiddish." Attempts at introducing literacy tests had been vetoed by Grover Cleveland in 1891 and William Taft in 1913. Despite Wilson's objections the 1917 Immigration Act but it was still passed by Congress.

The 1924 Immigration Act was even more restrictive. Under this act only around 150,000 were permitted to enter the United States. As one of its critics, Emanuel Celler, pointed out: "We were afraid of foreigners; we distrusted them; we didn't like them. Under this act only some one hundred and fifty odd thousands would be permitted to enter the United States. If you were of Anglo-Saxon origin, you could have over two-thirds of the quota numbers allotted to your people. If you were Japanese, you could not come in at all. That, of course, had been true of the Chinese since 1880. If you were southern or eastern European, you could dribble in and remain on sufferance."

On this day in 1932 women's suffrage campaigner, Flora Mayor, died. Flora Mayor was a member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. However, she rejected the militant tactics of the Women Social & Political Union. In a letter to Alice in 1907 she explained how Annie Kenney had tried to persuade her to join the WSPU: "I saw the little Kenney again, to whom I feel quite warmhearted. She again implored me to join her, but I would have none of her, chiefly for your sake you stupid ass... I think it is rather cowardly of me when I do feel it is right and important."

In another letter in April 1908 Flora admitted she had been told by a friend, Emily Leaf, that Charlotte Despard and Anne Cobden Sanderson, "might take to bomb-throwing". She added that the women were "getting almost irresponsible through the strain of the one idea". However, she admitted that: "I feel just as keen on Suffrage. Why should one fool make any difference to me?"

On this day in 1969 Josephine Herbst died. Herbst was born in Sioux City, Iowa, on 5th March 1897. Raised in near-poverty, Herbst attended several colleges between periods of work. She developed radical political opinions and began contributing to the socialist journal, The Masses.

Herbst graduated from the University of California in Berkeley in 1919. She now moved to New York City and soon became associating with a group of radicals who were producing The Liberator. This included Crystal Eastman, Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Art Young, Claude McKay, Boardman Robinson, Michael Gold, Louis Fraina, Louise Bryant, Dorothy Day, Robert Minor, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, Maurice Becker, Helen Keller, Cornelia Barns, Louis Untermeyer, Hugo Gellert, K. R. Chamberlain and William Gropper.

As well as writing for The Liberator she also published short stories under the pseudonym Carlotta Geet in American Mercury and Smart Set, then edited by H.L. Mencken, for whom she had also worked as a publicity writer and editorial reader. Following an unhappy affair and near-breakdown, Herbst moved to Berlin in 1922. Two years later she fell in love with the writer John Hermann. They married in 1926. He was eight years her junior but it was his alcoholism that brought the relationship to an end.

In 1928 Josephine Herbst settled in Pennsylvania where she wrote several novels, including Money for Love (1929), Pity is not Enough (1933) and The Executioner Awaits (1934). She also contributed to radical magazines such as New Masses and The Nation. In 1935 she went to Nazi Germany as a special correspondent for the New York Post. In 1937 Herbst reported on the Spanish Civil War and during this period was a passionate supporter of the Popular Front government.

After returning to the United States she published Satan's Sergeants (1941). After Pearl Harbor, Herbst got a job as a propaganda writer for the Office of the Coordinator of Information, but was fired a few months later after background investigation by the FBI found that she had admitted in one article that she had voted for the American Communist Party but considered Earl Browder, the current leader, as "too timid."

According to Mari Jo Buhle: "From 1942, when she lost a government job for political reasons, to 1954, she endured government harassment in a variety of forms. Her further literary work meanwhile received scarce recognition."

On this day in 1976, Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl de la Warr, died. Herbrand Sackville, the son of Gilbert Sackville, 8th Earl De La Warr and Muriel De La Warr, was born at Bexhill on 20th June, 1900. His parents marriage had been in difficulty for some time and they were divorced in 1902.

Whereas his father was a strong supporter of the Conservative Party, his mother, was a Liberal and an active member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Herbrand's own political views were closer to those of his mother and at Eton and at Magdalen College, Oxford, began expressing socialist views.