Ruskin College: 1899-1915

Charles A. Beard was a student at DePauw University when he joined the Hull House social settlement in Chicago. In 1898 he arrived in England to study at Oxford University. He became friends with a fellow American student, Walter Vrooman, a Christian Socialist. Both men "undeniably held unorthodox views on class and gender politics" and decided that they wanted to do something about improving working-class education. (1)

In February, 1899 Beard and Vrooman established Ruskin Hall (later known as Ruskin College), a free university offering evening and correspondence courses for working class people. The two men received most of the funds for the project from Amne Vrooman. (2) It was named after the essayist John Ruskin (1819–1900), who had written extensively about adult education. (3) The idea was that "economics and sociology should be taught from the working-class point of view, although not to the exclusion of the official capitalist standpoint, if that was thought desirable". (4)

Ruskin College the Workman's University

Ruskin Hall was also called a "College of the People" and the "Workman’s University". It was to be a residential institution providing study opportunities for a whole year or for shorter periods as appropriate. The residential element of the College’s work in its early years was open to men only. Harold Pollins pointed out: "It was to be part of a nationwide movement in order to cater for the large number who wanted to study but would not be able to take time off work. Provision for them, women as well as men, would be in two parts: correspondence courses, and extension classes in their own localities taught by the Ruskin Hall Faculty and by other lecturers." (5)

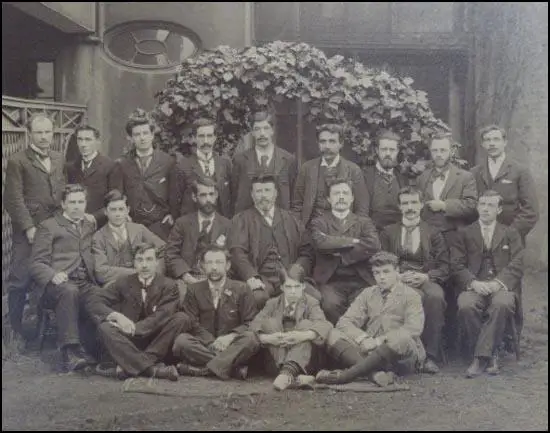

Robert Carruthers (top, third left), Bertram Wilson (top, eighth left), George Sims

(middle, first left), Dennis Hird (middle, fourth left), Frank Merry (middle, sixth left)

and Joseph Heywood (middle, seventh left).

Vrooman argued "that knowledge must be used to emancipate humanity, not to gratify curiosity, blind instincts and desire for respectability". At the public meeting that launched the college, he said: "The Ruskin students come to Oxford, not as mendicant pilgrims go to Jerusalem, to worship at her ancient shrines and marvel at her sacred relics, but as Paul went to Rome, to conquer in a battle of ideals". Dennis Hird was appointed as the the college's first principal. Hird was a member of the Social Democratic Federation and the former rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor, who had been sacked for a lecture he gave on the subject, Jesus the Socialist (it was later published as a pamphlet that sold 70,000 copies.) (6)

Charles A. Beard and Walter Vrooman established a Council to run Ruskin College. It consisted mainly of university men, whom he thought in sympathy with the ideals he set for the educational work on the institution. Three trade unionists, Richard Bell, General Secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, David Shackleton, the leader of the Weavers' Union and General Secretary of the London Society of Compositors, Charles W. Bowerman, also served on the Council. (7)

The students, almost all of them were sent on trade union scholarships worth £52. Some of the early students included Edward Traynor (a Yorkshire miner who had lost a leg in a accident at work), Robert Carruthers (a former railway booking clerk and a soldier in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers), Frank Merry (a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and secretary to Walter Vrooman), Joseph Heywood (an apprentice journalist on the Manchester Guardian) and Horace J Hawkins (a member of the Social Democratic Federation who was expelled from the college in November, 1899). The students were expected to carry out nearly all of the domestic duties, the cooking, serving, washing up the duties and the general cleanliness.

Dennis Hird v Hastings Lees-Smith

Janet Vaux has argued that "Ruskin... was conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power." The first eighteen students who joined the college on 22nd February 1899. By the end of the year the college had fifty-five students. (8)

At the college Dennis Hird taught sociology, evolution and formal logic. This meant that Hird was teaching sociology to his students at Ruskin College nearly 50 years before it was officially recognised by the University of Oxford. Hird also published a book explaining and popularising the theory of evolution, The Picture Book of Evolution (1906) Hird also introduced his students to the work of Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer and Émile Durkheim. (9)

The teaching of Hird had a dramatic impact on George Sims, a carpenter from Bermondsey: "I had tried for years to get a feeling of reality in religion, to feel that God and the Christ were of me and with me, the reality never came... But with the first reading of the Communist Manifesto, how the pamphlet appealed to something in me, some revolt against things as they are... We are neither fatalists, nor believers in miracles - simply people who know... the inevitability of social evolution, of development and progress based upon material needs as a stepping-stone to our higher selves." (9a)

Dennis Hird was especially interested in promoting the work of the American sociologist, Frank Lester Ward, a supporter of female and racial equality, who argued that poverty could be minimized or eliminated by the systematic intervention of the government. His work was very controversial and was banned in several countries, including Russia. Although his lectures on Ward was popular with the students they upset senior figures at Oxford University. One academic commented that before "Frank Lester Ward could begin to formulate that science of society which he hoped would inaugurate an era of such progress as the world had not yet seen, he had to destroy the superstitions that still held domain over the mind of his generation. Of these, laissez-faire was the most stupefying, and it was on the doctrine of laissez-faire that he trained his heaviest guns." (10)

In addition to Hird, three other lecturers were appointed by Vrooman. Hastings Lees-Smith, who also served as vice-principal, Bertram Wilson, who became general secretary of the college, and Alfred Hacking, a friend and supporter of Hird, who was placed in charge of the correspondence students. Almost all of the students arrived on trade union scholarships worth £52. (11)

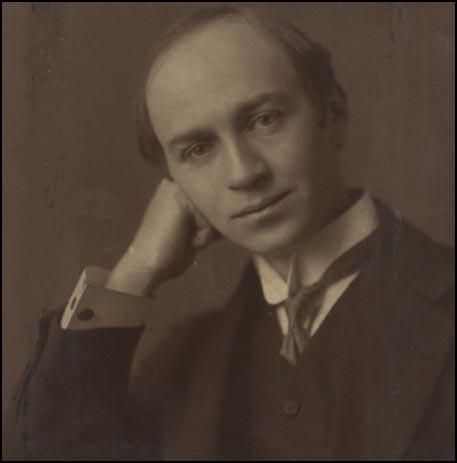

Hastings Lees-Smith disagreed with the politics of Hird. He was educated for an army career, first at the Aldenham School and then at the Royal Military Academy, but as a result of "a weak constitution" he left to join Queen's College. In 1899 he graduated with second-class honours in history. A member of the Liberal Party he taught economics and as he was a supporter of the free-market he upset the socialist students at Ruskin. (12)

After two years Amne Vrooman, who had divorced her husband, stopped funding Ruskin College. The general secretary of the college, was forced to seek donations from private individuals. Bertram Wilson, General Secretary of Ruskin College sent out letters explaining why they needed donations. The letters showed that the authorities were already undermining the intentions of the founders. For example, this one was written in 1907: "Madam, I hope I am doing right in bringing Ruskin College to your notice. It was founded eight years ago with the object of giving workingmen a sound practical knowledge of subjects which concern them as citizens, thus enabling them to view social questions sanely and without unworthy class bias." (13)

Most of the people who provided the funding of the college did not share the political beliefs of Hird. Janet Vaux has argued that "Ruskin... was conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power." (14)

Hastings Lees-Smith complained about the teaching of sociology as it tended to radicalize the students. Dennis Hird replied with a quote the objectives of Walter Vrooman, the founder of Ruskin College: "We shall take men who have been merely condemning our social institutions, and will teach them instead how to transform those institutions, so that in place of talking against the world, they will begin methodically and scientifically to possess the world, to refashion it, and to cooperate with the power behind evolution in making it a joyous abode of, if not a perfected humanity, at least a humanity earnestly and rationally striving towards perfection". (15)

The students became increasingly disturbed by the economic teaching of Hastings Lees-Smith. At the time the Miners' Federation of Great Britain were attempting to negotiate with the Coal Owners Association a minimum wage for its members. Lees-Smith used his lectures to condemn this strategy on the grounds that it would cause unemployment and reduce investment. Sidney Webb, the Labour Party politician, who advocated the minimum wage, was accused of telling "a tissue of lies". (16)

One of the students, J. M. K. MacLachlan, wrote an article for the September edition of Young Oxford (the journal of the Ruskin College students): "The present policy of Ruskin College is that of a benevolent trader sailing under a privateer flag. Professing the aims dear to all socialists, she disavows those very principles by repudiating socialism. Let Ruskin College proclaim socialism; let her convert her name from a form of contempt into a canon of respect." (17)

Noah Ablett, a member of the South Wales Miners' Federation, began a course at Ruskin College in 1907. He was completely self-educated and after reading the works of Karl Marx, Daniel De Leon and Tom Mann, he became a committed socialist. According to his biographer, Hywel Francis, "he quickly made his mark on educational thinking at Ruskin, and organized classes in Marxian economics and history as an alternative to the traditional liberal curriculum". (18)

Bernard Jennings argues that Ablett had a considerable influence over the students at Ruskin: "Tensions began to build as increasing numbers of students became ardent socialists. They enjoyed Hird's lectures on sociology, a major element of which was the study of evolution, on which he had written a popular book. They disliked Lees Smith's lectures on economics, although acknowledging his ability as a teacher, because his adherence to current free-market theories was just as dogmatic as that of the left-wing students to Marxism." (19)

In 1907 Hastings Lees-Smith, who was later to become a Liberal Party MP, was appointed professor of economics at University College, but he did not relax his grip on Ruskin. Lees-Smith was Oxford University's man at the college and so he was appointed chairman of Ruskin College's executive committee and chief adviser on studies. He now had control over staff recruitment and appointed, Charles Stanley Buxton, aged 23 as vice-principal. His father was Charles Sydney Buxton, the President of the Board of Trade, another establishment figure. (20)

Lees-Smith also recruited Henry Sanderson Furniss to lecture on economics, who both shared his view "of the relationship between class improvement and education". Sanderson Furniss came to realise that he and Buxton were intended to carry on Lees Smith's campaign against Hird: "They were, however, ill-equipped to do so, or to provide an antidote to the Marxist ideas which Furniss criticised without knowing much about them. They knew little about teaching, and less about working-class life." (21)

Although Dennis Hird was the Principal of Ruskin College, he was not consulted on these appointments. In 1899 his duties were defined as "to be in charge at Ruskin Hall". However, this was later changed to say all decisions were to be made by a House Committee of three, consisting of the Principal, the Vice-Principal and the General Secretary of the College. Buxton and Sanderson Furniss now joined forces to constantly outvote Hird. (22)

Noah Ablett rebelled against these developments and set up Marxist tutorial classes in the central valleys of the Welsh coalfield. In January 1909, Ablett and some of his followers established the Plebs League, an organisation committed to the idea of promoting left-wing education amongst workers. The name was taken from a pamphlet by Daniel De Leon. (23)

Over the next few months branches were established in five towns in the coalfields of South Wales. Arthur J. Cook and William H. Mainwaring were two early recruits to these classes. (24) Ablett was described as "a remarkable young man, a rebel of cosmopolitan, perhaps cosmic, importance" and "as an educator and ideologue, he was unique". (25)

In September 1907, Hastings Lees-Smith tried to marginalise Dennis Hird by proposing some new rules such as the requirement for regular essays and quarterly revision papers. In an attempt to deal with people like Ablett, students were forbidden to speak in public without the permission of the executive committee. It was made clear to Henry Sanderson Furniss that he was expected to try and reduce the radicalism in the college. (26)

In November 1908, Oxford University announced that it was going to take over Ruskin College. The chancellor of the university, George Curzon, was the former Conservative Party MP and the Viceroy of India. His reactionary views were well-known and was the leader of the campaign to prevent women having the vote. Curzon visited the college where he made a speech to the students explaining the decision. (27)

Dennis Hird replied to Curzon: "My Lord, when you speak of Ruskin College you are not referring merely to this institution here in Oxford, for this is only a branch of a great democratic movement that has its roots all over the country. To ask Ruskin College to come into closer contact with the University is to ask the great democracy whose foundation is the Labour Movement, a democracy that in the near future will come into its own, and, when it does, will bring great changes in its wake".

The author of The Burning Question of Education (1909) reported: "As he concluded, the burst of applause that emanated from the students seemed to herald the dawn of the day Dennis Hird had predicted. Without another word, Lord Curzon turned on his heel and walked out, followed by the remainder of the lecture staff, who looked far from pleased. When the report of the meeting was published in the press, the students noted that significantly enough Dennis Hird's reply was suppressed, and a few colourless remarks substituted." (28)

William Craik, a member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (later the National Union of Railwaymen) pointed out that his fellow students were "very perturbed at the direction in which the teaching and control of the College was moving, and by the failure of the trade union leaders to make any effort to change that direction. We new arrivals had little or no knowledge of what had been taking place at Ruskin before we got there. Most of us were socialists of one party shade or other." (29)

New rules such as the requirement for regular essays and quarterly revision papers were introduced. "This met with strong resistance from the majority of the students, who looked upon it as one more way of making the connection with the University still closer... Most of the students had come to Ruskin College on the understanding that there would be no tests other than monthly essays set and examined by their respective tutors, and afterwards discussed in personal interviews with them." (30)

In August 1908, Charles Stanley Buxton, the vice-principal of Ruskin College, published an article in the Cornhill Magazine. He wrote that "the necessary common bond is education in citizenship, and it is this which Ruskin College tries to give - conscious that it is only a new patch on an old garment." (31) It has been argued that "it read as if it had been written by someone who looked upon the workers as a kind of new barbarians whom he and his like had been called upon to tame and civilise". (32) The students were not convinced by this approach as Dennis Hird had told them about the quotation of Karl Marx: "The more the ruling class succeeds in assimilating members of the ruled class the more formidable and dangerous is its rule." (33)

In 1909 Lord George Curzon published Principles and Methods of University Reform. In the book he pointed out that it was vitally important to control the education of future leaders of the labour movement. He urged universities to promote the growth of an elite leadership and rejected the 19th century educational reformers call for reform on utilitarian lines to encourage "upward movement" of the capitalist middle class: "We must strive to attract the best, for they will be the leaders of the upward movement... and it is of great importance that their early training should be conducted on liberal rather than on utilitarian lines." (34)

In February, 1909, Dennis Hird was investigated in order to discover if he had "deliberately identified the college with socialism". The sub-committee reported back that Hird was not guilty of this offence but did criticise Henry Sanderson Furniss for "bias and ignorance" and recommended the appointment of another lecturer in economics, more familiar with working class views. Hastings Lees-Smith and the executive committee rejected this suggestion and in March decided to dismiss Hird for "failing to maintain discipline". He was given six months' salary (£180) in lieu of notice, plus a pension of £150 a year for life. (35)

It is believed that 20 students were members of the Plebs League. Its leader, Noah Ablett organised a students' strike in support of Hird. (36) The Ruskin authorities decided to close the college for a fortnight and then re-admit only students who would sign an undertaking to observe the rules. Of the 54 students at Ruskin at that time, 44 of them agreed to sign the document. However, the students decided that they would use the Plebs League and its journal, the Plebs' Magazine, to campaign for the setting up of a new and real Labour College. (37)

Dennis Hird received very little support from other advocates of working-class education. Albert Mansbridge, the

founder of the Workers' Educational Association (WEA) in 1903, blamed Hird's preaching of socialism for his dismissal. In a letter to a French friend, he wrote "the low-down practice of Dennis Hird in playing upon the class consciousness of swollen-headed students embittered by the gorgeous panorama ever before them of an Oxford in which they have no part." (38)

Noah Ablett took the lead in establishing an alternative to Ruskin College. He saw the need for a residential college as a cadre training school for the labour movement that was based on socialist values. George Sims, who had been expelled after his involvement in the Ruskin strike, played an important role in raising the funds for the project. On 2nd August, 1909, Ablett and Sims organised a conference that was attended by 200 trade union representatives. Dennis Hird, Walter Vrooman and Frank Lester Ward were all at the conference. (39)

Sims explained that the "last link which bound Ruskin College to the Labour Movement had been broken, the majority of the students had taken the bold step of trying to found a new college owned and controlled by the organised Labour Movement." (40) Ablett moved the resolution: "That this Conference of workers declares that the time has now arrived when the working class should enter the educational world to work out its own problems for itself." (41)

The conference agreed to establish the Central Labour College (CLC). The students rented two houses in Bradmore Road in Oxford. It was decided that "two-thirds of representation on Board of Management shall be Labour organisations on the same lines as the Labour Party constitution, namely, Trade Unions, Socialist societies and Co-operative societies." Most of the original funding came from the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF) and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). (42)

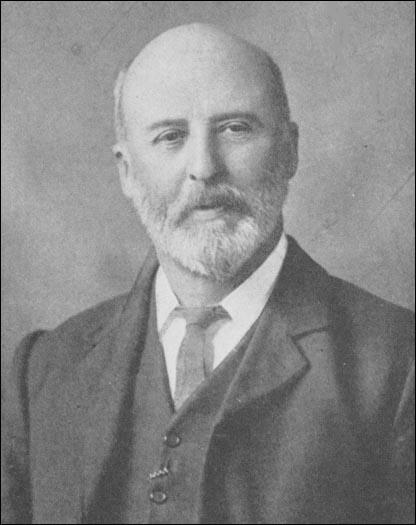

Dr. Gilbert Slater

At a meeting on 30th October, 1909, to discuss the sacking of Dennis Hird. The chairman, Hastings Lees-Smith, attempted to rush through a resolution endorsing the action of the Council of the College in discharging Hird. David Shackleton, the leader of the Weavers' Union, argued against the resolution. Eventually, it was decided to create a new Governing Council. It was now consisted of two representatives from the Trade Union Congress, two from the Co-operative Union and one from the Workingmen's Club and Institute Union. Oxford University had now lost control of Ruskin College.

Dr. Gilbert Slater was appointed as the new principal of Ruskin College. He was a member of the Labour Party and was chairman, vice-chairman, or secretary of many local committees connected with unemployment and the anti-sweating campaign. He had also just finished his PhD at the London School of Economics. Slater position was strengthened by the public support of the leading lights of the labour movement - George Lansbury, Keir Hardie, Sidney Webb, Will Crooks, Pete Curran, and J. A. Hobson.

As Harold Pollins has pointed out: "A major feature of the conflict at Ruskin in 1909 was its constitution. The striking students and their allies demanded that working-class education should be under the control of working-class organizations. Ruskin's governing council included Oxford University dons as well as others from outside the labour movement. Slater made his mark rapidly by recommending a change in the college's structure: in future only representatives of working-class organizations could be represented on the governing council." (43)

The new Governing Council consisted of: James Sexton and Charles W. Bowerman (Trade Union Council), Ben Tillett (General Federation of Trade Unions), A. E. Wood and W. H. Berry (Working Men’s Club and Institute Union), J. Hill and J. Jones (Amalgamated Society of Engineers) J.Cairns (Northumberland Miners’ Association) F. Thomas (Weavers’ Amalgamation) and S. Ledbury (Amalgamated Society of Toolmakers).

Under Slater's principalship Ruskin College settled down and flourished. In 1910 the University Diploma in Economics and Political Science was opened up to Ruskin candidates. In 1913 the new buildings in Walton Street, that had been built to replace the cottages that formerly housed the College, were opened. Student numbers expanded until the outbreak of the First World War. The college closed and there was no salary for Slater. He continued his work as Principal in an honorary capacity (i.e. unpaid) until he resigned his post at the College in the summer of 1915 to take up the post of Professor of Indian Economics at Madras University. (44)

Primary Sources

(1) Janet Vaux, The First Students at Ruskin College (27th May, 2016)

The college, which at that time was known as Ruskin Hall, had been founded in 1899 by three visiting Americans (Walter and Amne Vrooman and Charles Beard), who had conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power.

The different political currents of the period were reflected in debates about and within the college. By 1909, differences about college governance and the syllabus (especially the teaching of the theory of evolution and of Marxism), as well as increasingly poisonous relations among the college staff, led to the sacking of Dennis Hird, a student strike, and the setting up of the Central Labour College by the striking students, with Hird as its first principal.

(2) Hywel Francis, Noah Ablett : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

A member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), Ablett was self-educated, reading Karl Marx and other socialist writers. In 1907 he attended Ruskin College, Oxford, on a correspondence course scholarship, and later on a scholarship from the Rhondda no. 1 district of the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF). He quickly made his mark on educational thinking at Ruskin, and organized classes in Marxian economics and history as an alternative to the traditional liberal curriculum. Representing the college's Marxian Society he expressed his suspicions of the university's desire to help the education of working people, believing instead in independent working-class education (IWCE).

(3) Colin Waugh, The Lost Legacy of Independent Working-Class Education (January 2009)

Ruskin Hall grew partly out of the same impulses as the extension and settlement movements. But at the start, because of the way in which it was founded, it existed alongside these movements without a formal link. In the beginning, it was part of a broader project started by three people from the United States. Two of these people, Charles Beard, later a prominent historian in the US, and Walter Vrooman, had been students at Oxford University. The third was Vrooman`s wife, Amne, part of whose inheritance financed the project.

The Ruskin Hall in Oxford, set up in 1899, was from the outset drawn in two directions. It was both a labour college (that is, an institution controlled by trades unions and providing courses for their members) and a utopian colony. In its first two years some of the students were workers sponsored by their unions, but others were short-term, non-working-class visitors from overseas, or wellheeled cranks.

With Beard, Walter Vrooman (who was influenced by the Knights of Labour movement in the US) did try to organise a movement for working class education. They did this by founding colleges, by teaching classes themselves, by lobbying labour movement organisations, by travelling round England promoting their version of socialist education,

by creating a network of correspondence tuition, and by setting up the Ruskin College Education League for the purpose of making Ruskin College known in London and the provincial centres. Beard founded another Ruskin Hall in

Manchester, and others existed briefly in Birmingham, Liverpool, Birkenhead and Stockport...Working class students at Ruskin came to respect Hird so much that early issues of The Plebs Magazine carried adverts for plaster busts of Darwin, Herbert Spencer and Hird himself. Years later some former students still had these on their mantelpieces. As principal of Ruskin, Hird wrote to the British Steel Smelters Association to say that: "Many unions would be glad of an opportunity to send one of their most promising younger members for a year`s education in social questions". This gives us an important clue about what he thought the college was for. However, although Vrooman was a socialist, he was also a Christian, from a well-off nonconformist background. His main rebellion against this background had taken place at 13, when he took himself out of school. The US socialist publisher Charles Kerr was later to say of him that, although he possessed "the greatest enthusiasm for socialism

as he understands it, Vrooman is hopelessly erratic... he wants to be a dictator in whatever he is doing".By deciding to name their project after John Ruskin, Beard and the Vroomans showed that they wanted it to challenge the existing order, but also that, like the Guild of St George founded by Ruskin himself, its focus would be ethical as much as economic. They timed the inaugural meeting for Ruskin Hall in Oxford to coincide with John

Ruskin`s 80th birthday. At this meeting Vrooman described his aim in this way: "We shall take men who have been merely condemning our social institutions, and will teach them instead how to transform those institutions, so that in place of talking against the world, they will begin methodically and scientifically to possess the world, to refashion it, and to cooperate with the power behind evolution in making it a joyous abode of, if not a perfected humanity, at least a humanity earnestly and rationally striving towards perfection". These words reveal Vrooman`s intention that the world should be changed by action from below ("begin methodically and scientifically to possess the world... and to refashion it"). But they also reflect his religious feelings ("the power behind evolution", and the suggestion that humanity cannot be perfected) and his wish to prevent discontent getting out of hand.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)