Art Young

Art Young was born in Stephenson County, Illinois, on 14th January, 1866. His family moved to Monroe, Wisconsin, when he was a child to run a general store and a twenty-acre farm. When he was a boy Young borrowed a book from the local library that had been illustrated by Gustave Dore. Young was so impressed with these drawings that he decided to become an illustrator.

Young sent his drawings to journals in Chicago and at the age of seventeen had his first work accepted by the Judge Magazine. Soon after the publication of his first drawing, Young moved to the city where he studied at its Academy of Design. He paid for the course by illustrating news stories in the Chicago Evening Mail. Young soon developed a reputation as a talented artist and was offered work with the Chicago Daily News and the Chicago Inter-Ocean. In 1885 he married Elizabeth North and three years later they moved to New York City and Young became a student at the Arts Students League.

Young also had his cartoons published in Life and Puck and provided drawings to illustrate news stories for the Evening Journal. One of these assignments included a speech given by Keir Hardie, the British trade union leader and the first socialist member of the House of Commons. Later, Young recalled how listening to Hardie encouraged him to start questioning his previously held, conservative views.

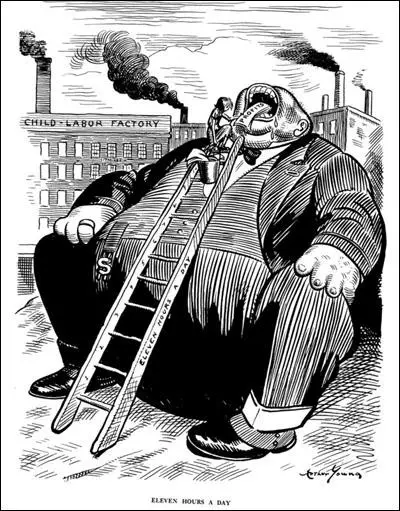

In March 1902 Young was commissioned to draw an anti-immigration picture for Life. After it was published he sent back the $100 cheque and vowed that in future he would only draw pictures that reflected his own political beliefs. By this time Young's work was so highly valued that newspapers and magazines were willing to accept his drawings attacking inequality and supporting causes he believed in such as women's rights.

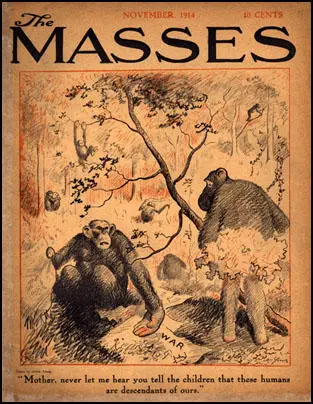

When Piet Vlag decided to start a new socialist magazine, The Masses, in 1910, he asked Young to join him. Other early members of the team included Louis Untermeyer and John Sloan. Organised like a co-operative, artists and writers who contributed to the journal shared in its management. According to Barbara Gelb: "After about a year and a half the Masses floundered and its tiny staff of contributors, which included the artist, John Sloan, the cartoonist, Art Young, and the poet, Louis Untermeyer, held an emergency session to rescue it. It was Young's idea to ask Max Eastman, a twenty-nine-year-old Columbia professor who had recently been dismissed for his radical views, to take over the editorship of the Masses."

In 1912 Max Eastman, a Marxist, agreed to become editor of the journal. In his first editorial, Eastman argued: "This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers."

Art Young later recalled: "I think we have the true religion. If only the crusade would take on more converts. But faith, like the faith they talk about in the churches, is ours and the goal is not unlike theirs, in that we want the same objectives but want it here on earth and not in the sky when we die."

Over the next few years The Masses published articles and poems written by people such as John Reed, Sherwood Anderson, Crystal Eastman, Hubert Harrison, Inez Milholland, Mary Heaton Vorse, Louis Untermeyer, Randolf Bourne, Dorothy Day, Helen Keller, William Walling, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge, Floyd Dell and Louise Bryant.

The Masses also published the work of important artists including John Sloan, Robert Henri, Alice Beach Winter, Mary Ellen Sigsbee, Cornelia Barns, Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Lydia Gibson, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

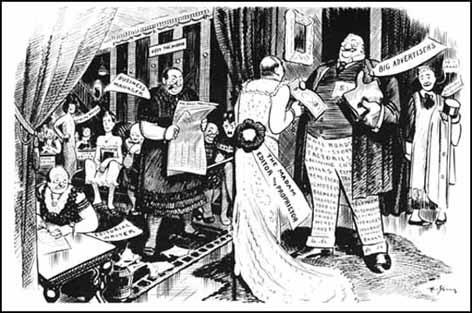

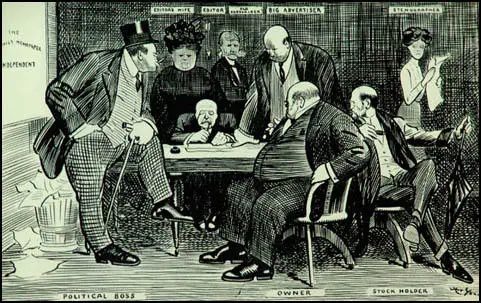

In 1913 Young and Max Eastman were charged with criminal libel after the publication of a cartoon, Poisoned at the Source. Floyd Dell later explained what happened: "The Masses decided to look into the case (a strike in West Virginia). It decided that if this thing were true, it ought to be stated without delicacy. The result was a paragraph warmly charging the Associated Press with having suppressed and colored the news of the strike in favour of the employers. Accompanying the paragraph was a cartoon presenting the same charge in a graphic form. Upon the basis of this cartoon and paragraph, William Rand, an attorney for the Associated Press, brought John Doe proceedings against the Masses." After the case was dismissed in the Municipal Court of New York City, Rand successfully approached the District Attorney and both men were arrested. Associated Press eventually dropped the case. However, after a year, the company decided to drop the law suit.

William L. O'Neill, the author of Echoes of Revolt: The Masses 1911-1917 (1966) has pointed out: "Art Young had that singular contempt for the pretensions of the press which only long and intimate associations produces. As a professional cartoonist he knew whereof he drew, and the scorn he lavished on the Associated Press was only part, as this drawing indicated, of the utter distaste he felt for the brothel economics of the industry as a whole."

At The Masses Young sometimes clashed with its art editor, John Sloan. Young believed that Sloan was more interested in art than socialism. When Sloan left in 1916 after a dispute with the more politically committed members of the co-operative, Young commented: "To me this magazine exists for socialism. That's why I give my drawings to it, anybody who doesn't believe in a socialist policy, as far as I go, can get out."

Although Young was his cartoons always had a political objective, they were often difficult to interpret. The dominant theme in his cartoons was to attack hypocrisy and show the real truth behind the official image. One cartoon for example, Respectability, published in August 1915, shows a well-dressed man, closing some curtains in his house. The critic, Richard Fitzgerald, in his book, Art and Politics (1973), argues that the man "who could be a railroad magnate, a pillar of society, is shown in a private moment of desperate anxiety and fear symbolically concealing objects that no doubt represent the various deviant tendencies behind the facade of respectability."

Young, like most of the people working for The Masses, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. This was reflected in Young's cartoons that attacked the behaviour of both sides in the conflict.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and H. J. Glintenkamp and articles by Max Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. In April, 1918, after three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of the defendants.

The second trial was held in January 1919. John Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, was also arrested and charged with the original defendants. Floyd Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933): "While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't conspired to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling." This time eight of the twelve jurors voted for acquittal. As the First World War was now over, it was decided not to take them to court for a third time.

Over the next few years Young had cartoons published in two radical journals he had helped to establish, The Liberator (1918-24) and Good Morning (1919-21). He also provided material for the Saturday Evening Post, The Nation, New Masses, Appeal to Reason, The New York Call and the New Leader.

In 1934 Young was in poor health and close and close to bankruptcy and so a group of friends organised a testimonial benefit in New York City. Young was too ill to attend but he sent a message to the event. "I'm a little worse for wear. But I will try to express myself hereafter with bigger and better bitterness. I don't know the meaning of dialectical materialism. All I know is that the cause of the workers is right and the rule of capitalism is wrong, and right will win."

Young published two autobiographies, On My Way (1928) and Art Young: His Life and Times (1939) and a book of his cartoons, The Best of Art Young (1936).

Art Young continued to produce politically committed cartoons until his death on 29th December 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) In his autobiography, On My Way, Art Young explained how his political views changed in 1910.

It was no thunderbolt revelation that hit me like the one that struck Paul of Tarsus. For years the truth about the underlying cause of the exploitation and misery of the world's multitudes had been knocking at the door of my consciousness, but not until that year did it begin to sound clearly. Now, I was past forty years of age and I knew definitely where I was going.

(2) Floyd Dell, The Masses (April 1914)

The Masses decided to look into the case (a strike in West Virginia). It decided that if this thing were true, it ought to be stated without delicacy. The result was a paragraph warmly charging the Associated Press with having suppressed and colored the news of the strike in favour of the employers. Accompanying the paragraph was a cartoon presenting the same charge in a graphic form. Upon the basis of this cartoon and paragraph, William Rand, an attorney for the Associated Press, brought John Doe proceedings against The Masses.

(3) Barbara Gelb, So Short a Time (1973)

Art Young was in Eastman's view, the hero of the trial. Young, at fifty-two, was a nationally famous political cartoonist, who had been the Washington correspondent for the Metropolitan until 1917, and a contributor to Life, The Saturday Evening Post, and Collier's, in addition to the Masses. A member of the Socialist Party, he was a crusader for women's suffrage, labor unions, and racial equality.

One of the prosecution's pieces of evidence was a cartoon Young had drawn, showing a capitalist, an editor, a politician, and a minister dancing a war dance, while the devil directed the orchestra; it was captioned, "Having Their Fling." The prosecutor asked him what he meant by the picture.

"Meant? What do you mean by meant? You have the picture in front of you."

"What did you intend to do when you drew this picture, Mr. Young?"

"Intend to do? I intended to draw a picture." "For what purpose?"

"Why, to make people think-to make them laugh-to express my feelings. It isn't fair to ask an artist to go into the metaphysics of his art."

"Had you intended to obstruct recruiting and enlistment by such pictures?"

"There isn't anything in there about recruiting and enlistment is there? I don't believe in war, that's all, and I said so."

After hearing the bulk of the testimony, Judge Hand dismissed the part of the indictment that accused the Masses of conspiring to cause mutiny and refusal of duty in the armed forces; the only charge for the jury to weigh was that of a "conspiracy" to obstruct the draft.

In summing up, Hillquit said, in part: "Constitutional rights are not a gift. They are a conquest by this nation, as they were a conquest by the English nation. They can never be taken away, and if taken away, and if given back after the war, they will never again have the same potent vivifying force as expressing the democratic soul of a nation. They will be a gift to be given, to be taken."

The prosecuting attorney, Earl Barnes, was "sincerely convinced" that the Masses staff should go to jail, Eastman recalled. Yet he seemed equally sincere in his reluctance to send them there, and in his summation to the jury, made numerous complimentary references to the individual talents of the defendants.

(4) In November 1934, Art Young was in poor health and close to bankruptcy and so a group of friends organised a testimonial benefit in New York. Young was too ill to attend but he sent a message to the event.

I'm a little worse for wear. But I will try to express myself hereafter with bigger and better bitterness. I don't know the meaning of dialectical materialism. All I know is that the cause of the workers is right and the rule of capitalism is wrong, and right will win.

(5) Art Young was interviewed by Gil Wilson in May, 1940.

I think we have the true religion. If only the crusade would take on more converts. But faith, like the faith they talk about in the churches, is ours and the goal is not unlike theirs, in that we want the same objectives but want it here on earth and not in the sky when we die.

Student Activities

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)