John Sloan

John Sloan, the son of a travelling salesman, was born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, on 2nd August, 1871. His family moved to Philadelphia and after he finished high school he worked for a booksellers.

Sloan studied briefly at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before finding work as an artist with the Philadelphia Inquirer (1892-95). This was followed by work at the Philadelphia Press (1895-1902), where he produced full-page colour pictures based on news stories.

In 1902 Sloan moved to New York where he worked as a magazine illustrator. Sloan's paintings were also exhibited in Chicago, Pittsburgh and New York City. In 1904 he met Robert Henri and became a member of what became known as the Ash Can School, a group of artists who painted pictures of everyday urban life. Other members associated with the group included George Bellows, Rockwell Kent and Edward Hopper.

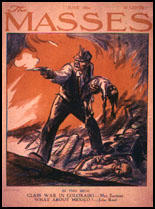

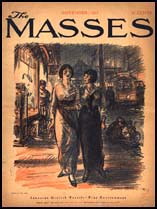

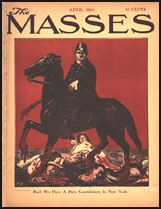

In 1910 Sloan joined the Socialist Party and the following year became art editor of the radical journal, The Masses. Although they were rarely paid, Sloan persuaded some of leading artists to provide pictures for the magazine. Artists such as Robert Henri, Stuart Davis, George Bellows, Rockwell Kent, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, K. R. Chamberlain, and Maurice Becker.

Floyd Dell later recalled: "At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, spoke up strongly for the artists."

Sloan was a strong supporter of woman suffrage and contributed drawing to the feminist magazines, Woman Voter and Woman's Journal. Sloan continued to work for The Masses until 1916, when he left over a dispute with Max Eastman about the captions being used with the cartoons.

Sloan became a teacher at the Arts Students League. After the First World War Sloan moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico where he painted local people. He later recalled: "When I painted the life of the poor, I was not thinking about them like a social worker - but with the eye of a poet who sees with affection." He also contributed illustrations to Collier's Magazine, Harper's Weekly and the Saturday Evening Post.

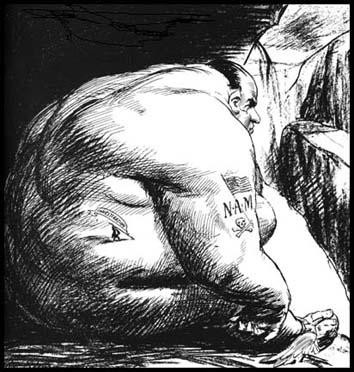

Manufacturers, The Masses (October, 1913)

Stephen Coppel, the author of The American Scene (2008) has pointed out: "Sloan was a prolific printmaker: between 1891 and 1940 he produced some three hundred etchings. He also tried lithography, but etching remained his true medium. He wrote about printmaking, focusing upon his personal experiences of the medium. He also produced more technical notes, giving a systematic guide to etching from how to ground the plate to the choice of paper used. His influence as one of the first chroniclers of the American scene and his technical abilities as an etcher would have a profound influence upon later American artists."

Sloan autobiography, Gist of Art, was published in 1939. In his book Sloan explained that: "I have always painted for myself and made my living by illustrating and teaching. I have never made a living from my painting." In his later years Sloan became increasingly concerned with studies of the nude in the 1940s.

John Sloan died on 7th September, 1951.

Primary Sources

(1) John Sloan, Gist of Art (1939)

The night the first copy of The Masses (under Max Eastman's editorship) came out, I sold seventy-eight copies. It was at a Suffrage parade. I went up to people, sometimes got on the running board of a car, saying, "Buy it. It will be worth ten dollars some day."

(2) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

I was paid twenty-five dollars a week for helping Max Eastman get out the magazine. My job on The Masses was to read manuscripts, bring the best of them to editorial meetings to be voted on, send back what we couldn't use, read proof, and 'make up' the magazine - all duties with which I was familiar; and also to help plan political cartoons and persuade the artists to draw them. I could submit my stories and poems anonymously to the editorial meetings, hear them discussed, and print them if they were accepted.

At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, spoke up strongly for the artists.

Nobody gained a penny out of the things published in the magazine; it was an honour to get into its pages, an honour conferred by vote at the meetings. Max Eastman and I did get salaries for editorial work; but that was regarded as dirty work, which ought to be paid for. We were actually a little republic in which, as artists, we worked for the approval of our fellows, not for money.

(3) John Sloan, The New York Scene: 1909-1913 (1965)

When I painted the life of the poor, I was not thinking about them like a social worker - but with the eye of a poet who sees with affection.

(4) John Sloan, Gist of Art (1939)

Ever since the great War broke out in 1914 this world has been a crazy place to live in. I hate war and I put the hatred into cartoons in the Masses. I had great hopes for the world's socialist parties until 1914. Then I saw how they fell apart. Some of the leaders were killed; the emotional patterns of national pride set one country against another. I became disillusioned.

(5) Stephen Coppel, The American Scene (2008)

Sloan was a prolific printmaker: between 1891 and 1940 he produced some three hundred etchings. He also tried lithography, but etching remained his true medium. He wrote about printmaking, focusing upon his personal experiences of the medium. He also produced more technical notes, giving a systematic guide to etching from how to ground the plate to the choice of paper used. His influence as one of the first chroniclers of the American scene and his technical abilities as an etcher would have a profound influence upon later American artists.