On this day on 21st February

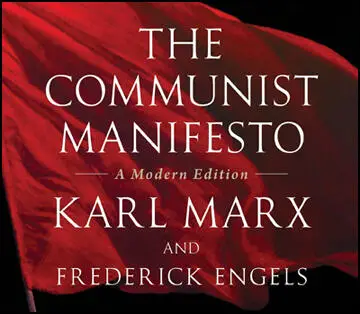

On this day in 1848 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published The Communist Manifesto. In June 1847 Engels produced a document called the Principles of Communism. It included the statement on what it meant to be a communist: "To organise society in such a way that every member of it can develop and use all his capabilities and powers in complete freedom and without thereby infringing the basic conditions of this society". He then goes on to explain how communism was to be achieved: "By the elimination of private property and its replacement by community of property."

Marx used this document as a first draft of the pamphlet entitled The Communist Manifesto. Marx finished the 12,000 word pamphlet in six weeks. Unlike most of Marx's work, it was an accessible account of communist ideology. Written for a mass audience, the book summarised the forthcoming revolution and the nature of the communist society that would be established by the proletariat. It has been claimed that it is the most widely read political pamphlet in human history.

The pamphlet begins with the assertion: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." Marx argued that if you are to understand human history you must not see it as the story of great individuals or the conflict between states. Instead, you must see it as the story of social classes and their struggles with each other. Marx explained that social classes had changed over time but in the 19th century the most important classes were the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. By the term bourgeoisie Marx meant the owners of the factories and the raw materials which are processed in them. The proletariat, on the other hand, own very little and are forced to sell their labour to the capitalists.

Marx believed that these two classes are not merely different from each other, but also have different interests. He went on to argue that the conflict between these two classes would eventually lead to revolution and the triumph of the proletariat. With the disappearance of the bourgeoisie as a class, there would no longer be a class society. "Just as feudal society was burst asunder, bourgeois society will suffer the same fate."

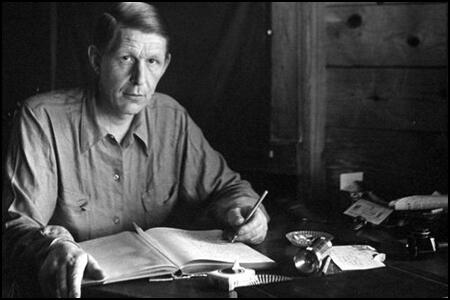

On this day in 1907 Wystan Hugh Auden, the son of a doctor, was born in York. Auden was educated at Gresham School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he gained a third class honours degree in 1928.

While at university Auden emerged as a promising poet. His early books include Poems (1930), The Orators (1932), The Dance of Death (1933) and Look Stranger! (1936). In collaboration with Christopher Isherwood he also wrote the plays The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935) and The Ascent of F6 (1936).

In January 1937 Auden went to Spain to support the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War. He visited Barcelona and Valencia where he wrote articles on the war for the New Statesman. When he returned to England he was active in the campaign in favour of the Popular Front government.

Auden's poem, Spain 1937, caused an impact on European left-wing intellectuals. In later years, Auden rejected his Marxist past and described the poem as "trash" and that he was "ashamed to have written."

Auden emigrated to the United States with Christopher Isherwood in 1939. During the Second World War he published The Double Man (1941) and For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio (1944).

In 1947 Auden became an American citizen. He completely rejected his left-wing past and his post-war work reflected his growing interest in religion. This included The Age of Anxiety (1947), Nones (1951), The Shield of Achilles (1955) The Old Man's Road (1956), Homage to Clio (1960), About this House (1967),City Walls and Other Poems (1969), American Graffiti (1971) and Epistle to a Godson (1972).

On this day in 1910 Douglas Bader, the son of a soldier who died as a result of the wounds suffered in the First World War, was born in London. A good student, Bader won a scholarship to St Edward's School in Oxford. An excellent sportsman, Bader won a place to the RAF College in Cranwell where he captained the Rugby team and was a champion boxer.

Bader was commissioned as an officer in the Royal Air Force in 1930 but after only 18 months he crashed his aircraft and as a result of the accident had to have both legs amputated.

Discharged from the RAF he found work with the Asiatic Petroleum Company. On the outbreak of the Second World War was allowed to rejoin the RAF.

A member of 222 Squadron, Bader, flying a Hawker Hurricane, he took part in the operation over Dunkirk and showed his ability by bringing down a Messerschmitt Bf109 and a Heinkel He111.

Bader was now promoted by Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory and was given command of 242 Squadron, which had suffered 50 per cent casualties in just a couple of weeks. Determined to raise morale, Bader made dramatic changes to the organization. This upset those in authority and was ordered to appear before Hugh Dowding, the head of Fighter Command.

The squadron's first sortie during the Battle of Britain on 30th August, 1940, resulted in the shooting down of 12 German aircraft over the Channel in just over an hour. Bader himself was responsible for downing two Messerschmitt 110.

Bader had strong ideas on tactics and did not always follow orders. He took the view that RAF fighters should be sent out to meet the German planes before they reached Britain. Hugh Dowding rejected this strategy as he believed it would take too long to organise.

Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, the commander of No. 11 Fighter Group, also complained complained that Bader's squadron should have done more to protect the air bases in his area instead of going off hunting for German aircraft to shoot down.

When William Sholto Douglas became head of Fighter Command, he developed what became known as the Big Wing strategy. This involved large formations of fighter aircraft deployed in mass sweeps against the Luftwaffe over the English Channel and northern Europe. Although RAF pilots were able to bring down a large number of German aircraft, critics claimed that they were not always available during emergencies and prime targets became more vulnerable to bombing attacks.

This strategy suited Bader and during the summer of 1941 he obtained 12 kills. His 23 victories made him the fifth highest ace in the RAF. However, on 9th August 1941, he suffered a mid-air collision down near Le Touquet, France. He parachuted to the ground but both his artificial legs were badly damaged.

Bader was taken to a hospital and with the help of a French nurse managed to escape. He reached the home of a local farmer but was soon arrested and sent to a prison camp. After several attempts to escape he was sent to Colditz.

Bader was freed at the end of the Second World War and when he returned to Britain he was promoted to group captain. He left the Royal Air Force in 1946 and became managing director of Shell Aircraft until 1969 when he left to become a member of the Civil Aviation Authority Board.

Paul Brickhill's book, Reach for the Sky, was published in 1954 and was later made into a movie. Bader's autobiography, Fight for the Sky appeared in 1973. Douglas Bader, who was knighted in 1976, died on 5th September, 1982.

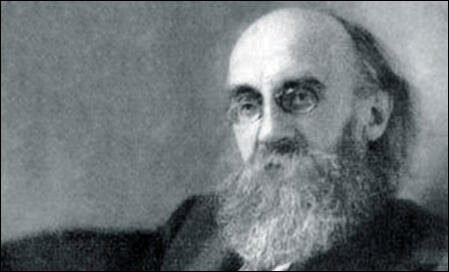

On this day in 1919 Kurt Eisner was assassinated. On the outbreak of the First World War, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) leader, Friedrich Ebert, ordered members in the Reichstag to support the war effort. Eisner supported Ebert until documents were published suggesting that Wilhelm II was responsible for starting the conflict. In April 1917 left-wing members of the Social Democratic Party formed the Independent Socialist Party. Members included Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Rudolf Breitscheild, Julius Leber, Ernst Thälmann and Rudolf Hilferding. Later that year Eisner was arrested and charged with inciting a strike of munitions workers. He spent 9 months in Stadelheim Prison, before being released during the General Amnesty in October, 1918.

On 28th October, 1918, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany.

Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party in Munich, called for a general strike. As Paul Frölich has pointed out: "They (Eisner and his political supporters) were enthusiastic about the idea of the political strike especially because they regarded it as a weapon which could take the place of barricade-fighting, and it seemed a peaceable weapon into the bargain."

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds."

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "On 7th November, 1918, the city was paralysed by the strike. Auer (the SDP leader) turned up to address what he expected to be a peaceful demonstration, to find the most militant section of it composed of armed soldiers and sailors, gathered behind the bearded Bohemian figure of Eisner and a huge banner reading Long Live the Revolution. While the Social Democrat leaders stood aghast, wondering what to do, Eisner led his group off, drawing much of the crowd behind it, and made a tour of the barracks. Soldiers rushed to the windows at the sound of the approaching turmoil, exchanged quick words with the demonstrators, picked up their guns and flocked in behind."

Kurt Eisner led the large crowd into the local parliament building, where he made a speech where he declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. Eisner explained that his program would be based on democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a republic.

Eisner wrote in a letter dated 14th November to Gustav Landauer: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Others who arrived in the city to support the new regime included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution.

Eisner had the support of the 6,000 workers of the munitions factory in Munich that was owned by Gustav Krupp. Many of them had come from northern Germany and were much more radical than those of Bavaria. The city was also a staging post for troops withdrawing from the Western Front. It is estimated that the majority of the 50,000 soldiers also supported Eisner's revolution. The anarcho-communist poet, Erich Mühsam, and the left-wing playwright, Ernst Toller, were other important figures in the rebellion.

On 9th November, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and the Chancellor, Max von Baden, handed power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy and was keen for one of the his grandsons to replace Wilhelm.

In Germany elections were held for a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution for the new Germany. As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League."

Paul Frölich has argued: "The enemies of the revolution had worked circumspectly and cunningly. On 10th November Ebert and the General Army Headquarters concluded a pact whose preliminary aim was to defeat the revolution. During that month there were bloody clashes between workers. During this month there were bloody clashes between workers and returning front-line soldiers who had been stirred up by the authorities. On military drill-grounds special troops, in strict isolation from the civilian population, were being ideologically and militarily trained for civil war."

On 29th December, 1918, Friedrich Ebert gave permission for the publishing of a Social Democratic Party leaflet that attacked the activities of the Spartacus League, led by Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches and Clara Zetkin: "The shameless doings of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg besmirch the revolution and endanger all its achievements. The masses cannot afford to wait a minute longer and quietly look on while these brutes and their hangers-on cripple the activity of the republican authorities, incite the people deeper and deeper into a civil war, and strangle the right of free speech with their dirty hands. With lies, slander, and violence they want to tear down everything that dares to stand in their way. With an insolence exceeding all bounds they act as though they were masters of Berlin."

In Bavaria Eisner was forced to form a coalition government with the Social Democratic Party. During this period the living conditions of the Munich workers and soldiers were rapidly deteriorating. It was not a surprise when at the election on 12th January, 1919, in Bavaria, Eisner and the Independent Socialist Party received only 2.5 per cent of the total vote.

Eisner remained in power by granting concessions to the SDP. This included agreeing to the establishment of a regular security force to maintain order. As Chris Harman pointed out: "In office without any power base of his own, he was forced to behave in an increasingly arbitrary and apparently irrational manner". On 21st February, 1919, Eisner decided to resign. On his way to parliament he was assassinated by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land."

Konrad Heiden wrote in his biography of Adolf Hitler: "Like Lenin, he had the peasants and workers on his side, but all the educated classes, the officers, officials, students, against him; in such a case there is no difference between Christian and Jew. Belatedly the intellectuals grew ashamed of their cowardice; they grew ashamed when they perceived that there was no danger. Their radical hatred found its embodiment in leagues like the Thule Society. While the Rosenbergs, the Hesses, the Eckarts, and others whose names have been forgotten were still planning - such an act, after all, was dangerous - a man whom they had insulted and cast aside got ahead of them. The League had rejected Count Anton Arco-Valley, a young officer, for being of Jewish descent on one side. Determined to shame his insulters by an example of courage, he shot Eisner down in the midst of his guards on the open street. A second later he himself lay on the ground, with a bullet through his chest. Eisner's secretary, Fechenbach, sprang forward and saved the assassin from being trampled by the boots of the infuriated soldiers. A mass insurrection broke out, a soviet republic was proclaimed."

The novelist, Heinrich Mann, a supporter of the Independent Socialist Party, spoke at Eisner's funeral and at his memorial three weeks later. Thomas Mann, who was deeply opposed to socialism, commented that Heinrich claimed that "Eisner had been the first intellectual at the head of a German state... in a hundred days he had had more creative ideas than others in fifty years, and... had fallen as a martyr to truth. Nauseating!"

On this day in 1919 peace campaigner Alice Wheeldon died. Alice Wheeldon's health never recovered from her time in prison.. At Alice's funeral, her friend John S. Clarke, made a speech that included the following: "She was a socialist and was enemy, particularly, of the deepest incarnation of inhumanity at present in Great Britain - that spirit which is incarnated in the person whose name I shall not insult the dead by mentioning. He was the one, who in the midst of high affairs of State, stepped out of his way to pursue a poor obscure family into the dungeon and into the grave... We are giving to the eternal keeping of Mother Earth, the mortal dust of a poor and innocent victim of a judicial murder."

On 31st January 1917, Alice Wheeldon, Hettie Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason were arrested and charged with plotting to murder the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson, the leader of the Labour Party.

At Alice's home they found Alexander Macdonald of the Sherwood Foresters who had been absent without leave since December 1916. When arrested Alice claimed: "I think it is a such a trumped-up charge to punish me for my lad being a conscientious objector... you punished him through me while you had him in prison... you brought up an unfounded charge that he went to prison for and now he has gone out of the way you think you will punish him through me and you will do it."

Sir Frederick Smith, the Attorney-General, was appointed as prosecutor of Alice Wheeldon. Smith, the MP for Liverpool Walton, had previously been in charge of the government's War Office Press Bureau, which had been responsible for newspaper censorship and the pro-war propaganda campaign.

The case was tried at the Old Bailey instead of in Derby. According to friends of the accused, the change of venue took advantage of the recent Zeppelin attacks on London. As Nicola Rippon pointed out in her book, The Plot to Kill Lloyd George (2009): "It made for a prospective jury that was likely to be both frightened of the enemy and sound in their determination to win the war."

The trial began on 6th March 1917. Alice Wheeldon selected Saiyid Haidan Riza as her defence counsel. He had only recently qualified as a lawyer and it would seem that he was chosen because of his involvement in the socialist movement.

In his opening statement Sir Frederick Smith argued that the "Wheeldon women were in the habit of employing, habitually, language which would be disgusting and obscene in the mouth of the lowest class of criminal." He went on to claim that the main evidence against the defendants was from the testimony of the two undercover agents. However, it was disclosed that Alex Gordon would not be appearing in court to give his evidence.

Basil Thomson, the Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, argued in his book, The Story of Scotland Yard (1935) that Gordon was an agent who "was a person with a criminal history, or he had invented the whole story to get money and credit from his employer."

Herbert Booth said in court that Alice Wheeldon had confessed to him that she and her daughters had taken part in the arson campaign when they were members of the Women's Social and Political Union. According to Booth, Alice claimed that she used petrol to set fire to the 900-year-old church of All Saints at Breadsall on 5th June 1914. She added: "You know the Breadsall job? We were nearly copped but we bloody well beat them!"

Booth also claimed on another occasion, when speaking about David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson she remarked: "I hope the buggers will soon be dead." Alice added that Lloyd George had been "the cause of millions of innocent lives being sacrificed, the bugger shall be killed to stop it... and as for that other bugger Henderson, he is a traitor to his people." Booth also claimed that Alice made a death-threat to Herbert Asquith who she described as "the bloody brains of the business."

Herbert Booth testified that he asked Alice what the best method was to kill David Lloyd George. She replied: "We (the WSPU) had a plan before when we spent £300 in trying to poison him... to get a position in a hotel where he stayed and to drive a nail through his boot that had been dipped in the poison, but he went to France, the bugger."

Sir Frederick Smith argued that the plan was to use this method to kill the prime minister. He then produced letters in court that showed that Alice had contacted Alfred Mason and obtained four glass phials of poison that she gave to Booth. They were marked A, B, C and D. Later scientific evidence revealed the contents of two phials to be forms of strychnine, the others types of curare. However, the leading expert in poisons, Dr. Bernard Spilsbury, under cross-examination, admitted that he did not know of a single example "in scientific literature" of curate being administered by a dart.

Major William Lauriston Melville Lee, the head of the PMS2, who employed Herbert Booth and Alex Gordon, gave evidence in court. He was asked by Saiyid Haidan Riza if Gordon had a criminal record. He refused to answer this question and instead replied: "I have already already explained to you that I do not know the man. I cannot answer questions on matters beyond my own knowledge." He admitted he had instructed Booth to "get in touch with people who might be likely to commit sabotage".

Alice Wheeldon turned the jury against her when she refused to swear on the Bible. The judge responded by commenting: "You say that an affirmation will be the only power binding upon your conscience?" The implication being that the witness, by refusing to swear to God, would be more likely to be untruthful in their testimony." This was a common assumption held at the time. However, to Alice, by openly stating that she was an atheist, was her way of expressing her commitment to the truth.

Alice admitted that she had asked Alfred Mason to obtain poison to use on dogs guarding the camps in which conscientious objectors were held. This was supported by the letter sent by Mason that had been intercepted by the police. It included the following: "All four (glass phials) will probably leave a trace but if the bloke who owns it does suspect it will be a job to prove it. As long as you have a chance to get at the dog I pity it. Dead in 20 sec. Powder A on meat or bread is ok."

She insisted that Gordon's plan involved the killing of the guard dogs. He had told her that he knew of at least thirty COs who had escaped to America and that he was particularly interested in "five Yiddish still in the concentration camp." Gordon also claimed he had helped two other Jewish COs escape from imprisonment.

Alice Wheeldon admitted that she had told Alex Gordon that she hoped David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson would soon be dead as she regarded them as "a traitor to the labouring classes?" However, she was certain that she had not said this when she handed over the poison to Gordon.

When Hettie Wheeldon gave evidence she claimed that It was Gordon and Booth who suggested that they assassinate the prime minister. She replied: "I said I thought assassination was ridiculous. The only thing to be done was to organise the men in the work-shops against compulsory military service. I said assassination was ridiculous because if you killed one you would have to kill another and so it would go on."

Hettie said that she was immediately suspicious of her mother's new friends: "I thought Gordon and Booth were police spies. I told my mother of my suspicions on 28 December. By the following Monday I was satisfied they were spies. I said to my mother: "You can do what you like, but I am having nothing to do with it."

In court Winnie Mason admitted having helped her mother to obtain poison, but insisted that it was for "some dogs" and was "part of the scheme for liberating prisoners for internment". Her husband, Alfred Mason, explained why he would not have supplied strychnine to kill a man as it was "too bitter and easily detected by any intended victim". He added that curare would not kill anything bigger than a dog.

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union, told the court: "We (the WSPU) declare that there is no life more valuable to the nation than that of Mr Lloyd George. We would endanger our own lives rather than his should suffer."

Saiyid Haidan Riza argued that this was the first trial in English legal history to rely on the evidence of a secret agent. As Nicola Rippon pointed out in her book, The Plot to Kill Lloyd George (2009): "Riza declared that much of the weight of evidence against his clients was based on the words and actions of a man who had not even stood before the court to face examination." Riza argued: "I challenge the prosecution to produce Gordon. I demand that the prosecution shall produce him, so that he may be subjected to cross-examination. It is only in those parts of the world where secret agents are introduced that the most atrocious crimes are committed. I say that Gordon ought to be produced in the interest of public safety. If this method of the prosecution goes unchallenged, it augurs ill for England."

The judge disagreed with the objection to the use of secret agents. "Without them it would be impossible to detect crimes of this kind." However, he admitted that if the jury did not believe the evidence of Herbert Booth, then the case "to a large extent fails". Apparently, the jury did believe the testimony of Booth and after less than half-an-hour of deliberation, they found Alice Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason guilty of conspiracy to murder. Alice was sentenced to ten years in prison. Alfred got seven years whereas Winnie received "five years' penal servitude."

The Derby Mercury reported: "It was a lamentable case, lamentable to see a whole family in the dock; it was sad to see women, apparently of education, using language which would be foul in the mouths of the lowest women. Two of the accused were teachers of the young; their habitual use of bad language made one hesitate in thinking whether education was the blessing we had all hoped."

On 13th March, three days after the conviction, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, published an open letter to the Home Secretary that included the following: "We demand that the Police Spies, on whose evidence the Wheeldon family is being tried, be put in the Witness Box, believing that in the event of this being done fresh evidence will be forthcoming which will put a different complexion on the case."

Basil Thomson, the Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, was also unconvinced by the guilt of Alice Wheeldon and her family. Thomson later said that he had "an uneasy feeling that he himself might have acted as what the French call an agent provocateur - an inciting agent - by putting the idea into the woman's head, or, if the idea was already there, by offering to act as the dart-thrower."

Alice was sent to Aylesbury Prison where she began a campaign of non-cooperation with intermittent hunger strikes. One of the doctors at the prison reported that many prisoners were genuinely frightened of Alice who seemed to "have a devil" within her. However, the same doctor reported that she also had many admirers and had converted several prisoners to her revolutionary political ideas.

Some members of the public objected to Alice Weeldon being forced to eat. Mary Bullar wrote to Herbert Samuel, the Home Secretary and argued: "Could you not bring in a Bill at once simply to say that forcible feeding was to be abandoned - that all prisoners alike would be given their meals regularly and that it rested with them to eat them or not as they chose - it was the forcible feeding that made the outcry so there could hardly be one at giving it up!"

Alice was moved to Holloway Prison. As she was now separated from her daughter, Winnie Mason, she decided to go on another hunger strike. On 27th December 1917, Dr Wilfred Sass, the deputy medical officer at Holloway, reported that Alice's condition was rapidly declining: "Her pulse is becoming rather more rapid... of poor volume and rather collapsing... the heart sounds are rapid... at the apex of the heart." It was also reported that she said she was "going to die and that there would be a great row and a revolution as the result."

Winnie Mason wrote to her mother asking her to give up the hunger strike: "Oh Mam, please don't die - that's all that matters... you were always a fighter but this fight isn't worth your death... Oh Mam, for one kiss from you! Oh do get better please do, live for us all again."

On 29th December David Lloyd George sent a message to the Home Office that he had "received several applications on behalf of Mrs Wheeldon, and that he thought on no account should she be allowed to die in prison." Herbert Samuel was reluctant to take action but according to the official papers: "He (Lloyd George) evidently felt that, from the point of view of the government, and in view especially of the fact that he was the person whom she conspired to murder, it was very undesirable that she should die in prison."

Alice was told she was to be released from prison because of the intervention of the prime minister. She replied: "It was very magnanimous of him... he has proven himself to be a man." On 31st December, Hettie Wheeldon took her mother back to Derby.

Sylvia Pankhurst, writing in the Workers' Dreadnought, claimed that Alice was "mothering half a dozen other comrades with warm hospitality in a delightful old-fashioned household, where comfort was secured by hard work and thrifty management." She added that Alice was forced to close her shop but had "made the best of the situation by using her shop window for growing tomatoes."

The campaign continued to get Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason released from prison. On 26th January 1919 it was announced that the pair had be allowed out on licence at the request of Premier Lloyd George."

Hettie Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alice Wheeldon.

On this day in 1923 Arthur Maundy Gregory was found guilty of selling honours. Gregory the second of three sons of Francis Maundy Gregory (1849–1899), clergyman, and his wife, Elizabeth Ursula Mayow (1847–1936), was born at 9 Portland Terrace, Southampton on 1st July, 1877. After attending Banister Court School he passed the Oxford University entrance examination and went into residence there as a non-collegiate student in 1895.

Gregory originally intended to become a clergyman but left university shortly before his finals and began appearing on the stage. In 1900 he acted in the theatrical company of Ben Greet. In 1902 he took the role of the butler in The Brixton Burglary. He the became manager of the theatre company run by Frank Benson, but was dismissed for fraud in 1906.

According to his biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines: "In 1908 he (Gregory) made his earliest known attempt at blackmail. Harold Davidson, afterwards notorious as the vicar of Stiffkey, who had been his boyhood friend, induced Lord Howard de Walden and other rich men to finance Maundy-Gregory (as he then called himself) in the Combine Attractions Syndicate which crashed in 1909. Gregory next edited a gossip sheet, Mayfair (1910–14). As a sideline he ran a detective agency specializing in credit rating based on information supplied by hoteliers and restaurateurs."

Gregory became friends with Vernon Kell, Director of the Home Section of the Secret Service Bureau with responsibility for investigating espionage, sabotage and subversion in Britain. Kell employed Gregory to compile dossiers of possible foreign spies living in London. Later, Gregory was recruited by Sidney Reilly, the top agent the recently formed MI6. He also did work for Basil Thomson, the head of Special Branch.

According to Brian Marriner: "Gregory, a man of diverse talents, had various other sidelines. One of them was compiling dossiers on the sexual habits of people in high positions, even Cabinet members, especially those who were homosexual. Gregory himself was probably a latent homosexual, and hung around homosexual haunts in the West End, picking up information.... There is a strong suggestion that he may well have used this sort of material for purposes of blackmail."

Basil Thomson later admitted that it was Gregory who told him about the homosexual activities of Sir Roger Casement. "Gregory was the first person... to warn that Casement was particularly vulnerable to blackmail and that if we could obtain possession of his diaries they could prove an invaluable weapon with which to fight his influence as a leader of the Irish rebels and an ally of the Germans."

On 21st April 1916, Casement was arrested in Rathoneen and subsequently arrested on charges of treason, sabotage and espionage. As Noel Rutherford has pointed out: "Casement's diaries were retrieved from his luggage, and they revealed in graphic detail his secret homosexual life. Thomson had the most incriminating pages photographed and gave them to the American ambassador, who circulated them widely. They were a significant, if unmentioned, ingredient in the trial and subsequent execution of Casement." Later, Victor Grayson claimed that Gregory had planting the diaries in Casement's lodgings.

Arthur Maundy Gregory now moved in circles where he made friends with the rich and famous. This included the Duke of York, who later became King George V. In 1918 he met Frederick Guest and David Lloyd George, the prime minister of the coalition government. It has been argued by Gregory's biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines: "In 1918 Lord Murray of Elibank introduced Gregory to his successor as Liberal chief whip, Frederick Guest, as a potential intermediary between rich men who wanted honours and the Lloyd George coalition which needed money. Guest and his successor, Charles McCurdy, together with Lloyd George's press agent Sir William Sutherland, used Gregory as a tout to build up the Lloyd George political fund by the sale of honours."

The author Brian Marriner has pointed out: "It has been claimed by some that Gregory even suggested the introduction of the new order of the OBE in order to coin more income - even from OBEs he got £20 commission a time.... Gregory had an office in Whitehall at 38 Parliament Street, which had a rear office in Cannon Row (he was always one to leave himself an escape route)." Knighthoods cost about £10,000 and baronetcies £40,000 and it has been estimated that Gregory received commission of about £30,000 a year.

In early 1918 Basil Thomson asked Gregory to spy on Victor Grayson, the former MP for Colne Valley, who was described as a "dangerous communist revolutionary". Gregory was told: "We believe this man may have friends among the Irish rebels. Whatever it is, Grayson always spells trouble. He can't keep out of it... he will either link up with the Sinn Feiners or the Reds." Gregory became friendly with Grayson. David Howell, Grayson's biographer, writes that "Grayson subsequently lived in apparent affluence - a contrast with his recent poverty - in a West End flat. His associates included Maundy Gregory... The significance of this relationship and the source of Grayson's income remain unknown."

During the summer of 1919 Victor Grayson became aware that Gregory was spying on him. He told a friend: "Just as he spied on me, so now I'm spying on him. One day I shall have enough evidence to nail him, but it's not going to be easy." It is not known how he obtained the information but at a public meeting in Liverpool he accused David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, of corruption. Grayson claimed that Lloyd George was selling political honours for between £10,000 and £40,000. Grayson declared: "This sale of honours is a national scandal. It can be traced right down to 10 Downing Street, and to a monocled dandy with offices in Whitehall. I know this man, and one day I will name him." The monocled dandy was Gregory.

At the beginning of September 1920, Victor Grayson was beaten up in the Strand. This was probably an attempt to frighten Grayson but he continued to make speeches about the selling of honours and threatening to name the man behind this corrupt system. On the 28th September Grayson was drinking with friends when he received a telephone message. Grayson told his friends that the had to go to Queen's Hotel in Leicester Square and would be back shortly.

Later that night, George Jackson Flemwell was painting a picture of the Thames, when he saw Grayson entering a house on the river bank. Flemwell knew Grayson as he had painted his portrait before the war. Flemwell did not realize the significance of this as the time because Grayson was not reported missing until several months later. An investigation carried out in the 1960s revealed that the house that Grayson entered was owned by Arthur Maundy Gregory. Victor Grayson was never seen alive again. It is believed he was murdered but his body was never found.

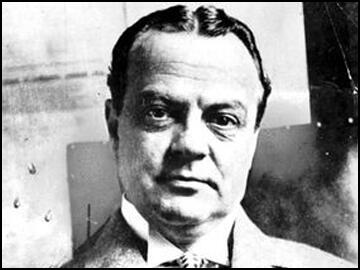

Richard Davenport-Hines described Gregory as being "short, paunchy, bald, rubicund, monocled, and epicene." Davenport-Hines added: "He wore ostentatious jewellery, including a green scarab ring he claimed had been Wilde's, and used to fidget with a rose-coloured diamond carried in his waistcoat pocket which supposedly had belonged to Catherine the Great. His manner was grandiose, mysterious, watchful, and confidential."

Arthur Maundy Gregory continued to work closely with Vernon Kell and Basil Thomson in their efforts to stop left-wing politicians from gaining power in Britain. It has been claimed by Brian Marriner that he told prospective buyers of honours that the money would be used by the government to "fight Bolshevism and revolution".

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservatives had 258, Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. As MacDonald had to rely on the support of the Liberal Party, he was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. The only significant measure was the Wheatley Housing Act which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rent to working-class families.

Arthur Maundy Gregory, like other members of establishment, was appalled by the idea of a Prime Minister who was a socialist. As Gill Bennett pointed out in her book, Churchill's Man of Mystery (2009): "It was not just the intelligence community, but more precisely the community of an elite - senior officials in government departments, men in "the City", men in politics, men who controlled the Press - which was narrow, interconnected (sometimes intermarried) and mutually supportive. Many of these men... had been to the same schools and universities, and belonged to the same clubs. Feeling themselves part of a special and closed community, they exchanged confidences secure in the knowledge, as they thought, that they were protected by that community from indiscretion."

In September 1924 MI5 intercepted a letter signed by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, and Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were urged to promote revolution through acts of sedition. Hugh Sinclair, head of MI6, provided "five very good reasons" why he believed the letter was genuine. However, one of these reasons, that the letter came "direct from an agent in Moscow for a long time in our service, and of proved reliability" was incorrect.

Vernon Kell and Sir Basil Thomson the head of Special Branch, were also convinced that the Zinoviev Letter was genuine. Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret but someone leaked news of the letter to the Times and the Daily Mail. The letter was published in these newspapers four days before the 1924 General Election and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald and the Labour Party.

In a speech he made on 24th October, Ramsay MacDonald suggested he had been a victim of a political conspiracy: "I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot... The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?"

After the election it was claimed that Arthur Maundy Gregory and Sidney Reilly, had forged the letter and that Major George Joseph Ball (1885-1961), a MI5 officer, leaked it to the press. In 1927 Ball went to work for the Conservative Central Office where he pioneered the idea of spin-doctoring. Later, Desmond Morton, who worked under Hugh Sinclair, at MI6 claimed that it was Stewart Menzies who sent the Zinoviev letter to the Daily Mail.

In 1927 Gregory acquired the Ambassador Club at 26 Conduit Street in Mayfair. As Richard Davenport-Hines pointed out: "Gregory... with ingratiating flamboyance, he entertained prospective clients, collected gossip, and planted stories. He displayed a gold cigarette case given him by the duke of York, afterwards George VI, at whose wedding he was a steward. In 1929 Gregory bought Burke's Landed Gentry. In 1931 he leased Deepdene Hotel near Dorking, which became a favourite assignation for rich Londoners desiring a dirty weekend." Gregory also "diversified into the less profitable market of foreign decorations, and after being received into the Roman Catholic church in 1932 did brisk business in papal honours."

Stanley Baldwin appointed John C. Davidson as chairman of the Conservative Party organization. Davidson had a major problem raising money for the Conservative Party to fight future elections. One of the problems was Gregory who had for several years been successfully working for David Lloyd George in raising funds for the Liberal Party. As Robert Rhodes James has pointed out: "Davidson's strategy had a brilliant simplicity. He introduced what was in effect a spy into the Gregory organization, whose task it was to obtain the list of Gregory's clients. Davidson then saw to it that no one on that list obtained any honour or award of any kind. Gregory's position depending upon his ability to deliver the goods for which his clients had paid him. By ensuring that none of his clients received any award, Davidson devastatingly undermined Gregory's entire scheme of operations."

In 1932 Gregory was in financial difficulties. He was under pressure to repay to the executors of Sir George Watson (1861-1930) £30,000 advanced for a barony he never received. At the time he was living platonically with a retired musical actress, Mrs Edith Marion Rosse. She had £18,000 in the bank but when Gregory asked her for a loan she refused saying the money was for her "old age".

On 15th September 1932, Roose died and left all her money to Gregory, in a will scrawled on the back of a menu card from the Carlton Hotel. Gregory supervised her burial, specifying a riverside plot in the churchyard at Bisham on the Thames. He ordered the coffin lid to be left unsealed and the grave to be dug unusually shallow - it was only 18 inches from the surface.

Despite inheriting £18,000 from Rosse, Gregory was still in debt to several people he had acquired money from people for honours that they had not received. Gregory now attempted to sell a knighthood to Lieutenant Commander Edward Billyard-Leake. He pretended he was interested and then reported the matter of Scotland Yard. Gregory was arrested on 4th February, 1933, and charged with corruption. He now turned it to his advantage as he was now able to blackmail famous people into paying him money in return for not naming them in court.

The leaders of the Conservative Party were especially worried about Gregory's testimony in court. The chairman of the party, John C. Davidson, approached him, warned that he could not avoid conviction, but undertook that if he kept silent the authorities would be lenient. After a discreet trial he changed his plea to guilty on 21st February, 1933 and received the lightest possible sentence of two months and a fine of £50. According to Richard Davenport-Hines: "On his release from Wormwood Scrubs he was met at the prison gates by a friend of Davidson who took him to France, gave him a down payment, and promised him an annual pension of £2000."

Following a complaint about Gregory by Edith Marion Rosse's niece, who expected to be left money in her will, the police exhumed the body on 28th April 1933. The coffin was waterlogged. Bernard Spilsbury, the forensic scientist used by the police, had little doubt that the burial arrangements Gregory had made were intentional, since "the effect of water on decaying remains would make it impossible to detect the presence of certain poisons."

Arthur Maundy Gregory was arrested by the German authorities in November 1940, Gregory was confined in Drancy Camp, where his health deteriorated without the whisky upon which he depended. He died of cardiac failure, aggravated by a swollen liver, on 28th September 1941, at Val de Grâce Hospital, Paris.

On this day in 1938 Anthony Eden resigned as Foreign Secretary. On 7th June 1935 Stanley Baldwin became prime minister and appointed Eden as his Foreign Secretary. Henry (Chips) Channon commented: "He has had a meteoric rise, young Anthony. I knew him well at Oxford, where he was mild, aesthetic, handsome, cultivated and interested in the East - now at thirty-eight he is Foreign Secretary. There is hardly a parallel in our history. I wish him luck; I like him; but I have never had an exaggerated opinion of his brilliance, though his appearance is magnificent."

The Conservative Party feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government. On the 19th July, 1936, Spain's prime minister, José Giral, sent a request to Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, for aircraft and armaments. The following day the French government decided to help and on 22nd July agreed to send 20 bombers and other arms. This news was criticized by the right-wing press and the non-socialist members of the government began to argue against the aid and therefore Blum decided to see what his British allies were going to do.

Anthony Eden received advice that "apart from foreign intervention, the sides were so evenly balanced that neither could win." Eden warned Blum that he believed that if the French government helped the Spanish government it would only encourage Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to aid the Nationalists. Edouard Daladier, the French war minister, was aware that French armaments were inferior to those that Franco could obtain from the dictators. Eden later recalled: "The French government acted most loyally by us." On 8th August the French cabinet suspended all further arms sales, and four days later it was decided to form an international committee of control "to supervise the agreement and consider further action."

Baldwin told Eden that he hoped that the next war Nazi Germany would fight would be against the Soviet Union. In a letter to Churchill, Baldwin argued: "I do not believe Germany wants to move West because West would be a difficult programme for her, and if she does it before we are ready. I quite agree the picture is perfectly awful. If there is any fighting in Europe to be done, I should like to see the Bolshies and the Nazis doing it."

On 28th May, 1937, Stanley Baldwin resigned and replaced by Neville Chamberlain. Eden initially welcomed the prospect of a more pro-active Downing Street involvement in foreign affairs, especially as Chamberlain shared his view that war with Germany could be avoided through rearmament and collective security backed by the League of Nations. Eden wrote to Chamberlain: "I entirely agree that we must make every effort to come to terms with Germany".

As Chancellor of the Exchequer Chamberlain had resisted attempts to increase defence spending. He now changed his mind and asked the defence policy requirements committee to look at different ways of funding this expenditure. It was suggested that £1.1 billion was financed through increased taxation and £400 million coming from increased government borrowing. It was suggested that of this sum, £80 million should be spent in air-raid precautions.

Over the next two years Chamberlain's Conservative government became associated with the foreign policy that later became known as appeasement. Chamberlain believed that Germany had been badly treated by the Allies after it was defeated in the First World War. He therefore thought that the German government had genuine grievances and that these needed to be addressed. He also thought that by agreeing to some of the demands being made by Adolf Hitler of Germany and Benito Mussolini of Italy, he could avoid a European war.

Joachim von Ribbentrop was ambassador to London in August, 1936. His main objective was to persuade the British government not to get involved in Germany territorial disputes and to work together against the the communist government in the Soviet Union. During this period Von Ribbentrop told Hitler that the British "were so lethargic and paralyzed that they would accept without complaint any aggressive moves by Nazi Germany."

According to Christopher Andrew, the author of Defence of the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5 (2010) MI5 was receiving information from a diplomat by the name of Wolfgang zu Putlitz, who was working in the German Embassy in London. Putlitz told MI5 that "He (Ribbentrop) regarded Mr Chamberlain as pro-German and said he would be his own Foreign Minister. While he would not dismiss Mr Eden he would deprive him of his influence at the Foreign Office. Mr Eden was regarded as an enemy of Germany." Putlitz constantly provided clear warnings that negotiations with Hitler and Rippentrop were likely to be fruitless and the only way to deal with Nazi Germany was to stand firm. Putlitz told MI5 that her policy of appeasement was "letting the trump cards fall out of her hands. If she had adopted, or even now adopted, a firm attitude and threatened war, Hitler would not succeed in this kind of bluff".

Baldwin was critical of the government's appeasement policy. He complained to Anthony Eden that his own work "in keeping politics national instead of party" had been rendered worthless by the actions of Neville Chamberlain. Eden replied that Chamberlain was attempting to "return to class warfare in its bitterest form". However, at this time he supported Chamberlain's appeasement policy because he believed that Britain needed time to rearm. However, as Keith Middlemas, the author of Diplomacy of Illusion: British Government and Germany, 1937-39 (1972), has pointed out: "While Eden held to the policy of keeping Germany guessing long enough to give Britain time to rearm, so that he could negotiate from a position of strength, Chamberlain, conscious of time running out, preferred to settle the outstanding accounts at once."

Anthony Eden slowly came into conflict with Chamberlain over the conduct of foreign policy. Chamberlian confided to his sister: "I fear the difference between Anthony and me is more fundamental than he realises. At bottom he is really dead against making terms with the dictators". As a result Chamberlain bypassed Eden, whom he saw as a hindrance to his wish for Anglo-Italian rapprochement, writing in his diary of a letter to Mussolini, after a private meeting with Count Grandi, the Italian ambassador in London, in July 1937, "I did not show my letter to the Foreign Secretary, for I had the feeling that he would object to it."

Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador to Berlin, upset Eden and Sir Robert Vansittart, his boss at the Foreign Office, by attending the annual Nuremberg Rally. Henderson told Eden that he was regarded as "too pro-Nazi or pro-German". However, he believed that sometimes it was necessary to impose a dictatorship. He considered Antonio Salazar, "the present dictator of Portugal" one of the "wisest statesmen which the post-war period has produced in Europe". He argued that Hitler had probably gone too far with the Nuremberg Laws but "dictatorships are not always evil and, however anathema the principle may be to us, it is unfair to condemn a whole country, or even a whole system. because parts of it are bad."

Henderson admitted in his autobiography, Failure of a Mission (1940), that his comments gave "most offence to the left wing". However, he believed that that the British people should pay more "attention to the great social experiment which was being tried out in Germany" and condemned those who suggested that "our old democracy has nothing to learn from Nazism". Henderson argued that "in fact, many things in the Nazi organisation and social institutions... which we might study and adapt to our own use with great profit both to the health and happiness of our own nation and old democracy."

In November, 1937, Neville Chamberlain announced he was sending his friend, and fellow appeaser, Lord Halifax, to meet Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring in Germany. Anthony Eden was furious when he discovered this and felt he was being undermined as foreign secretary. One historian has commented: "Eden and Chamberlain seemed like two horses harnessed to a cart, both pulling in different directions."

Neville Chamberlain invited Konstantin von Neurath, the German foreign minister, to London. On 26th November, 1937, Chamberlain recorded his objectives in the negotiations: "It was not part of my plan that we should make, or receive, any offers. What I wanted to do was to convince Hitler of our sincerity and to ascertain what objectives he had in mind... Both Hitler and Göring said separately and emphatically that they had no desire or intention of making war and I think we may take this as correct, at any rate for the present. Of course they want to dominate Eastern Europe; they want as close a union with Austria as they can get, without incorporating her in the Reich."

Anthony Eden made it clear to the prime minister that he was unwilling to force President Eduard Beneš of Czechoslovakia, to make concessions. William Strang, a senior figure in the Foreign Office, also urged caution over these negotiations: "Even if it were in our interest to strike a bargain with Germany, it would in present circumstances be impossible to do so. Public sentiment here and our existing international obligations are all against it."

In the cabinet Eden had few supporters. Duff Cooper , Secretary of State for War, argued in his autobiography, Old Men Forget (1953): "I had been glad when Eden had become Foreign Secretary and I had always given him my support in Cabinet when he needed it. I believed that he was fundamentally right on all the main problems of foreign policy, that he fully understood how serious was the German menace and how hopeless the policy of appeasement. Not being, however, a member of the Foreign Policy Committee, I was ignorant of how deep the cleavage of opinion between him and the Prime Minister had become. It is much to his credit that he abstained from all lobbying of opinion and sought to gain no adherents either in the Cabinet or the House of Commons."

Nevile Henderson, who was in favour of an agreement with Hitler, warned the British government that Nazi Germany was building up its armed forces. In January 1938 he reported: "The rearmament of Germany, if it has been less spectacular because it is no longer news, has been pushed on with the same energy as in previous years. In the army, consolidation has been the order of the day, but there is clear evidence that a considerable increase is being prepared in the number of divisions and of additional tank units outside those divisions. The air force continues to expand, at an alarming rate, and one can at present see no indication of a halt. We may well soon be faced with a strength of between 4000 and 5000 first-line aircraft.... Finally, the mobilisation of the civilian population and industry for war, by means of education, propaganda, training, and administrative measures, has made further strides. Military efficiency is the god to whom everyone must offer sacrifice. It is not an army, but the whole German nation which is being prepared for war."

On 4th February, 1938, Adolf Hitler sacked the moderate Konstantin von Neurath as Foreign Minister, and replaced him with the hard-line, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Eden argued that this move made it even more difficult to get an agreement with Hitler. He was also opposed to further negotiations with Benito Mussolini about withdrawing from its involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Eden stated that he completely "mistrusted" the Italian leader.

At a Cabinet meeting Chamberlain made it clear that he was unwilling to back down over the issue. Anthony Eden resigned on 20th February 1938. He told the House of Commons the following day: "I do not believe that we can make progress in European appeasement if we allow the impression to gain currency abroad that we yield to constant pressure. I am certain in my own mind that progress depends above all on the temper of the nation, and that temper must find expression in a firm spirit. This spirit I am confident is there. Not to give voice it is I believe fair neither to this country nor to the world."

Winston Churchill, the leader of the Conservative Party opposition to appeasement in parliament, argued: "The resignation of the late Foreign Secretary may well be a milestone in history. Great quarrels, it has been well said, arise from small occasions but seldom from small causes. The late Foreign Secretary adhered to the old policy which we have all forgotten for so long. The Prime Minister and his colleagues have entered upon another and a new policy. The old policy was an effort to establish the rule of law in Europe, and build up through the League of Nations effective deterrents against the aggressor. Is it the new policy to come to terms with the totalitarian Powers in the hope that by great and far-reaching acts of submission, not merely in sentiment and pride, but in material factors, peace may be preserved."

Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, also supported Eden in his action against the government. He accused Neville Chamberlain of "an abject surrender to the dictators". Attlee added: "There can be no doubt that it is a tremendous victory for Herr Hitler. Without firing a shot, by the mere display of military force, he has achieved a dominating position in Europe which Germany failed to win after four years of war. He has overturned the balance of power in Europe. He has destroyed the last fortress of democracy in Eastern Europe which stood in the way of his ambition. He has opened his way to the food, the oil and the resources which he requires in order to consolidate his military power, and he has successfully defeated and reduced to impotence the forces that might have stood against the rule of violence."

Anthony Eden later admitted: "My action had gained support in the Liberal and Labour Parties as well as in my own, and I had some encouragement to form a new party in opposition to Mr. Chamberlain's foreign policy. I considered this once or twice during the next few months, only to reject it as not being practical politics. Within the Conservative Party, I, and those who shared my views, were a minority of about thirty Members of Parliament out of nearly four hundred. Our number might be expected to grow if events proved us right, but the more complete the break, the more reluctant would the newly converted be to join us."

On this day in 1940 John Robert Lewis, the son of Eddie Lewis and and Willie Mae Carter Lewis, was born in Pike County, Alabama. After his parents bought their own farm - 110 acres for $300 - John, the third of 10 children, shared in the farm work, leaving school at harvest time to pick cotton, peanuts and corn. Their house had no plumbing or electricity. According to Katharine Q. Seelye: "John was responsible for taking care of the chickens. He fed them and read to them from the Bible. He baptized them when they were born and staged elaborate funerals when they died."

Lewis later claimed that as a small child he had only ever seen two white people. He went to local country schools, then to the segregated Pike county vocational high school, where his studying was hampered by the lack of access to Troy’s whites-only libraries. However, he was a dedicated student and dreamed of being the first person in his family to go to college. Lewis eventually enrolled at the Nashville American Baptist Theological Seminary, where on-campus work could help pay for his tuition. Eventually, he transferred and took his degree in religion and philosophy at nearby Fisk University.

While studying at Fisk he joined the civil rights movement, organising the sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. He later recalled: "The Nashville sit-ins became the first mass arrest in the sit-in movement, and I was taken to jail... I'll tell you, I felt so liberated. I felt so free. I felt like I had crossed over. I think I said to myself, 'What else can you do to me? You beat me. You harassed me. Now you have placed me under arrest. You put us in jail. What's left? You can kill us?'" Lewis went on to found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which became a prominent civil rights group, and served as its president for three years.

Lewis attended training sessions held by James Lawson, a committed pacifist, on non-violence strategies. "Over the next year, Lawson's worshops deepened his young disciple's religious and moral faith with visions of 'redemptive suffering,' 'soul force,' and the 'beloved community,' concepts that would inform and animate Lewis's long and influential career as a civil rights leader."

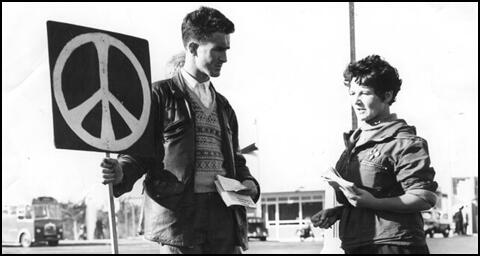

Transport segregation continued in some parts of the United States, so in 1961, the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) began to organize Freedom Rides. These civil rights campaigners challenged this status quo by riding interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. John Lewis commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South."

James Farmer, national director of CORE, and thirteen volunteers left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. The group included John Lewis, James Peck, James Farmer, James Zwerg, Genevieve Hughes, William E. Harbour, Frances Bergman, Walter Bergman, Albert Bigelow, Benjamin Elton Cox, Jimmy McDonald, Mae Frances Moultrie and Ed Blankenheimand. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death."

Governor John Malcolm Patterson of Alabama who had been swept to victory in 1958 on a stridently white supremacist platform. commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body." In his inaugural address Patterson declared: "I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state."

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, organized violence against the Freedom Riders with local KKK groups. Gary Thomas Rowe, an FBI informer, and member of the KKK, that the mob would have fifteen minutes to attack the Freedom Riders without any arrests being made. On 14th May, 1961, a mob of Klansmen, attacked the bus at Anniston, Alabama. Some, having just come from church, were dressed in their Sunday best. One man threw a bomb through a broken window. When the Freedom Riders left the bus they were attacked by baseball bats and iron bars. Genevieve Hughes said she would have been killed but an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode and the white bomb retreated. Eventually they were rescued by local police but no attempt was made to identify or arrest those responsible for the assault.

James Peck later explained: "When the Greyhound bus pulled into Anniston, it was immediately surrounded by an angry mob armed with iron bars. They set about the vehicle, denting the sides, breaking windows, and slashing tires. Finally, the police arrived and the bus managed to depart. But the mob pursued in cars. Within minutes, the pursuing mob was hitting the bus with iron bars. The rear window was broken and a bomb was hurled inside. All the passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames and was totally destroyed. Policemen, who had been standing by, belatedly came on the scene. A couple of them fired into the air. The mob dispersed and the injured were taken to a local hospital."

Another serious attack on the Freedom Riders took place in Montgomery. Gary Thomas Rowe was a member of the KKK who attacked them: "We made an astounding sight... men running and walking down the streets of Birmingham on Sunday afternoon carrying chains, sticks, and clubs. Everything was deserted; no police officers were to be seen except one on a street corner. He steppe3d off and let us go by, and we barged into the bus station and took it over like an army of occupation. There were Klansmen in the waiting room, in the rest rooms, in the parking area."

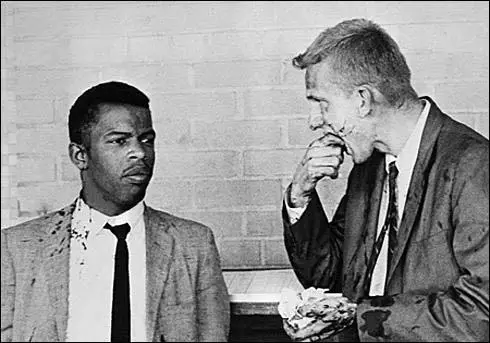

They adhered to Gandhian discipline and refused to fight back, but this only encouraged their attackers. John Lewis, James Peck, James Zwerg, and Walter Bergman, took severe beatings. Bergman, the oldest of the Freedom Riders at sixty-one, was knocked unconscious, and one of the attackers continued to stomp on his chest. Frances Bergman begged the Klansman to stop beating her husband, he ignored her plea. Fortunately, one of the other Klansmen - realizing that the defenceless Freedom Rider was about to be killed - eventually called a halt to the beating.

John Lewis was left unconscious in a pool of his own blood outside the Greyhound Bus Terminal in Montgomery, He spent countless days and nights in county jails. In several cities, police either looked the other way while crowds beat the riders or arrested the so-called outside agitators. When the Core leader James Farmer moved to discontinue the rides because of the violence, Lewis and his Nashville group took them over. Lewis eventually spent 40 days in jail in Mississippi, while the attorney general, Robert Kennedy, called for a “cooling-off” period and a halt to the rides. "But the Freedom Rides drew national attention to the desegregation campaign and attracted recruits. And the Kennedy administration began formal implementation of the Supreme Court decision."

Lewis was elected chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1963. That year, leaders of the civil rights movement decided to organize what became known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to take place on 28th August, 1963. Bayard Rustin was given overall control of the march. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigations, had been keeping a file on Rustin for many years. An FBI undercover agent managed to take a photograph of Rustin talking to King while he was having a bath. This photograph was then used to support false stories being circulated that Rustin was having a homosexual relationship with King. When surveillance established only that King was having sex with women other than his wife, FBI aides worked to "neutralise" him by slipping prurient information to the press.

The FBI passed on information about Rustin to white politicians in the Deep South who feared that a successful march on Washington would persuade President Lyndon B. Johnson to sponsor a proposed new civil rights act. Storm Thurmond led the campaign against Rustin making several speeches where he described him as a "communist, draft dodger and homosexual" and had his entire arrest file entered in the record.

A Justice Department lawyer of the time later commented: “Everything you have read about the FBI, how it was determined to destroy the movement, is true.” Accounts indicating that “the Bureau and its Director were openly racist,” and that “the Bureau set out to destroy black leaders simply because they were black leaders.” The historian David Garrow, has argued "The Bureau was strongly conservative, peopled with many right-wingers, and thus it selected people and organizations on the left end of the political spectrum for special and unpleasant attention."

Rustin managed to persuade the leaders of all the various civil rights groups to participate in the planned protest meeting at the Lincoln Memorial. This included Lewis, Martin Luther King (SCLC), Philip Randolph (Socialist Party), Roy Wilkins (NAACP), Floyd McKissick (CORE), James Farmer (Congress on Racial Equality), Witney Young (National Urban League) and Walter Reuther (AFL-CIO).

Most newspapers condemned the idea of a mass march on Washington. An editorial in the New York Herald Tribune warned that: If Negro leaders persist in their announced plans to march 100,000-strong on the capital…they will be jeopardizing their cause…. The ugly part of this particular mass protest is its implication of uncontained violence if Congress doesn’t deliver. This is the kind of threat that can make men of pride, which most Congressmen are, turn stubborn."

Rustin hoped that 100,000 marchers would participate. "We wanted to get everybody, from the whole country, into Washington by nine o'clock in the morning and out of Washington by sundown. This required all kinds of things that you had to think through. You had to think how many toilets you needed, where they should be. Where is your line of march? We had to consult doctors on exactly what people should bring to eat so that they wouldn't get sick... We had to arrange for drinking water. We had to arrange what we would do if there was a terrible thunderstorm that day." In fact, over a quarter of a million people, as many as 60,000 of them white.

At the Washington Monument staging area, a public address system came alive shortly after ten o'clock with the voice of Joan Baez, who entertained the early crowd by singing Oh Freedom. She was followed by Odetta singing I'm On My Way, and during her performance she was joined by Josh White, who had only recently returned to America from Europe after being blacklisted after appearing before the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Peter, Paul and Mary performed Blowin in the Wind and Bob Dylan sung Only A Pawn In Their Game, about the death of Medgar Evers. Other celebrities who attended included Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Diahann Carroll and James Garner. The veteran politician, Norman Thomas, the 79 year-old former leader of the Socialist Party of America said: "I'm glad I lived long enough to see this day."

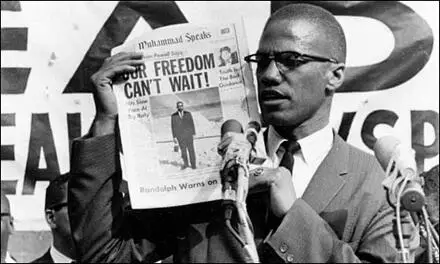

In his speech John Lewis said: "We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of. For hundreds and thousands of our brothers are not here. They have no money for their transportation, for they are receiving starvation wages or no wages, at all. In good conscience, we cannot support the administration's civil rights bill, for it is too little, and too late. There's not one thing in the bill that will protect our people from police brutality. This bill will not protect young children and old women from police dogs and fire hoses, for engaging in peaceful demonstrations. The voting section of this bill will not help thousands of black citizens who want to vote. It will not help the citizens of Mississippi, of Alabama, and Georgia, who are qualified to vote, but lack a 6th Grade education. 'One man, one vote,' is the African cry. It is ours, too."

John Lewis went on to argue that politicians in the two major parties were deeply divided over the subject of civil rights. Whereas they had the support of John F. Kennedy and Jacob Javits but was strongly opposed by Barry Goldwater and James Eastland: "We are now involved in revolution. This nation is still a place of cheap political leaders who build their careers on immoral compromise and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic and social exploitation. What political leader here can stand up and say, 'My party is the party of principles'? The party of Kennedy is also the party of Eastland. The party of Javits is also the party of Goldwater. Where is our party? We won't stop now. All of the forces of Eastland, Barnett, Wallace, and Thurmond won't stop this revolution. The time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South, through the Heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own "scorched earth" policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground - nonviolently. We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy."

Martin Luther King was the final speaker and made his famous I Have a Dream speech. "I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.' I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of "interposition" and "nullification," one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together."

King ended his speech with the words: "This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day. And when this happens, when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

In the 1960 Presidential Election campaign John F. Kennedy argued for a new Civil Rights Act. After the election it was discovered that over 70 per cent of the African American vote went to Kennedy. However, during the first two years of his presidency, Kennedy failed to put forward his promised legislation. The Civil Rights bill was brought before Congress in 1963 and in a speech on television, Kennedy pointed out that: "The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day; one third as much chance of completing college; one third as much chance of becoming a professional man; twice as much chance of becoming unemployed; about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year; a life expectancy which is seven years shorter; and the prospects of earning only half as much."