James Zwerg

James Zwerg was born in Appleton, Wisconsin, on 28th November, 1938. He was brought up by progressive parents. His father was a dentist who provided free dental care to the poor on one day per month. His parents were Christians who taught him that all humans are created equal. (1)

While at school Zwerg had never been in a classroom with a black student. This changed when he went to Beloit College to study sociology. Zwerg developed an interest in civil rights after his roommate, Robert Carter, who was an African-American from Alabama, gave him a copy of Martin Luther King's book, Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958) to read. (2)

Zwerg later recalled: "I witnessed prejudice against him (Carter)... we'd go to a lunch counter or cafeteria and people would get up and leave the table. I had pledged a particular fraternity and then found out that he was not allowed in the fraternity house. I decided that his friendship was more important than that particular fraternity, so I depledged." Zwerg decided to sign on for an exchange semester at the predominately black Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. “My main reason for going to Fisk,” Soon after arriving he signed up for a workshop on non-violence provided by James Lawson, (3) Zwerg said, “was that it gave me an opportunity to mirror the experiences of my black roommate at Beloit. Fisk was my first time being a minority. I wanted to know how I would be treated. It was a self-awareness and self-growth kind of thing.” (4)

Zwerg met John Lewis at Fisk who was active in the civil rights movement. Zwerg later recalled: "I was almost in awe of this young man. He was my age - 21 - but I had never met another person my age with his commitment. He exuded a quiet strength, almost an absolute certainty that he knew what he was doing - very open and very honest." Lewis had been involved in staging a sit-in at Woolworth's lunch counter with the intention of integrating eating establishments in Nashville. (5)

James Zwerg and the Civil Rights Movement

In October, 1960, Lewis and students involved in these sit-ins held a conference and established the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The organization adopted the Gandhian theory of nonviolent direct action. Zwerg joined the SNCC and his first demonstration was at a "whites only" movie house. According to one account: "Zwerg bought two movie-tickets, then handed one to an accompanying black man. When they tried to enter the theatre, Zwerg was hit with a monkey wrench, knocked out cold and dragged to the edge of the sidewalk." (6)

Transport segregation continued in the Deep South, so the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) began to develop strategies to bring it to an end. In February, 1961, CORE organised a conference in Kentucky where the organisation laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge the racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the Deep South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (7)

Freedom Riders

The first bus left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Members of CORE who travelled on the bus included John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes, James Farmer, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (8)

The second bus left on the 17th May and its passengers included William Barbee, William E. Harbour, Susan Herrmann, Lafayette Bernard, Susan Wilbur, James Zwerg, Salynn McCollum, Frederick Leonard, Lucretia Collins, Paul Brooks and Catherine Burks, Herrmann, 20, a student at Fisk University, Nashville, majoring in psychology, later recalled: "We were all prepared to die - and for a while Saturday I thought all 21 of us would die at the hands of that mob in Montgomery. We did not fight back. We do not believe in violence. We were freedom riders... trying to ride in buses through Alabama to New Orleans to help the cause of true freedom for all the races." (9)

The Freedom Riders were split between two buses. They traveled in integrated seating and visited "white only" restaurants. Governor John Malcolm Patterson of Alabama who had been swept to victory in 1958 on a stridently white supremacist platform, commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body." (10) In his inaugural address Patterson declared: "I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state." (11)

Frances Bergman and Benjamin Elton Cox in a white waiting-room (May, 1961)

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, organized violence against the Freedom Riders with local Ku Klux Klan groups. Gary Thomas Rowe, an FBI informer, and a member of the KKK, reported to his case officer that the mob would have fifteen minutes to attack the Freedom Riders without any arrests being made. Connor said he wanted the Riders to be beaten until "it looked like a bulldog got a hold of them." It was later revealed that J. Edgar Hoover knew the plans for the attack on the Freedom Riders in advance and took no action to prevent the violence. (12)

James Peck later explained: "When the Greyhound bus pulled into Anniston, it was immediately surrounded by an angry mob armed with iron bars. They set about the vehicle, denting the sides, breaking windows, and slashing tires. Finally, the police arrived and the bus managed to depart. But the mob pursued in cars. Within minutes, the pursuing mob was hitting the bus with iron bars. The rear window was broken and a bomb was hurled inside. All the passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames and was totally destroyed. Policemen, who had been standing by, belatedly came on the scene. A couple of them fired into the air. The mob dispersed and the injured were taken to a local hospital." (13)

Albert Bigelow later told a committee of inquiry: "Our bus, approaching Anniston, stopped while our driver conversed with the driver of an outgoing bus. A traveler from the bus leaving Anniston station. Outside, no police were in sight. During the fifteen minutes in Anniston, while the mob slashed tires and smashed windows, one policeman appeared in a brown uniform. He did nothing to stop vandalism but fraternized with the mob. A man in a white overall with a dark blue oval insignia on the breast was friendly with the policemen and consulted from time to time with the most active of the mob. Two policemen appeared and cleared a path. The bus left the station. There were no arrests. A few miles out on the highway to Birmingham a tire blow and we pulled to the roadside, the mob after us in about 50 cars. They surrounded us again, yelling and smashing windows, brandishing clubs, chains and pipes; I saw all three." (14)

Some, having just come from church, were dressed in their Sunday best. Ed Blankenheim later recalled: "As a matter of fact, one of the white men who boarded the bus said, 'Y'all ain't in Georgia now, y'all in Alabama.' And with that, he eventually set the bus on fire which was not a good place to be at the time. They held the door shut for maybe ten minutes, they held the door shut... The mob surrounded the bus. The cops would not let the mob get on the bus. So they threw an incendiary device aboard... They were mighty angry people. Really, really vicious. They, as I said, they did surround the bus. They threw a fire bomb aboard and held the door closed. One of the tanks blew up. One of the gas tanks blew up and Hank Thomas, who was one of the Freedom Riders, took advantage of it and was able to force open the bus door, thereby we got off. When we did get off... we had to run through the... these racists who beat us all like hell. Fortunately, well it didn't sound fortunate, the second fuel tank on the bus exploded, scared the hell out of the mob so they uh went on the other side of the highway and the object was to leave us there where we would be blown up." (15)

When the Freedom Riders left the bus they were attacked by baseball bats and iron bars. Genevieve Hughes said she would have been killed but an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode and the white bomb retreated. Eventually they were rescued by local police but no attempt was made to identify or arrest those responsible for the assault. (16)

Montgomery Bus Terminal Riot

James Zwerg was chosen to go on the third freedom ride that left Nashville, via Birmingham to Montgomery, on 17th May, 1961: "After we had talked it out and I was one of those chosen to go, I went back to my room and spent a lot of time reading the bible and praying. Because of what had happened in Birmingham and in Aniston, because our phones were tapped... none of us honestly expected to live through this. I called my mother and I explained to her what I was going to be doing. My mother's comment was that this would kill my father - and he had a heart condition - and she basically hung up on me. That was very hard because these were the two people who taught me to love and when I was trying to live love, they didn't understand." (17)

Organised by Diane Nash and Fred Shuttlesworth, the bus included only two white passengers, James Zwerg and Salynn McCollum. Other members of CORE included John Lewis, William E. Harbour, William Barbee, Charles Butler, Catherine Burks, Lucretia R. Collins and Allen Cason. Lewis said: "As far as I was concerned, it was time to go... Time was wasting. This was a crisis, and we needed to act." Several handed Nash sealed letters "to be mailed if they were killed. Collins explained: "We thought some of us would be killed. We certainly thought that some, if not all of us, would be severely injured." (18)

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, ordered the arrest of all the Freedom Riders when they arrived in the city. As the only white female, Salynn McCollum was placed in a special facility, and Collins and Burks were put in a cell with several other black women. All the men ended up in a dark and crowded cell that Lewis likened to a dungeon. "It had no mattresses or beds, nothing to sit on at all, just a concrete floor." Harbour and his cellmates adopted a strategy of Gandhian non-cooperation. Lewis added "We went on singing both to keep our spirits up and - to be honest - because we knew that neither Bull Conner nor his guards could stand it." (19)

James Zwerg later recalled: "Finally they took us to Birmingham Jail and fingerprinted us. They put me in solitary for a little while. Then they put me in with a fellow who was a felon. I mean, I'm in my suit and tie and I've got my pocket bible with me. I think he thought I was some clergyman making calls. Ultimately they threw me in a drunk tank, with about twenty guys in various states of inebriation, and announced in no uncertain terms that I was a Freedom Rider... I didn't know what was going to happen and I kind of said, 'How do you guys feel about this? Do you know what they're talking about?' And they started asking me some questions... I didn't know what had happened to the rest of the people on the bus. I began to see the state that some of drunks were in, and I tried to get some towels and clean up the guys who were sick. I just got talking to some of them and none of them ever laid a hand on me. Basically, we talked about what I believed and what they believed." (20)

William Pritchard, one of Birmingham's leading attorneys, claimed: "I have no doubt that the Negro basically knows that the best friend he's ever had in the world is the Southern white man. He'd do the most for him - always has and will continue to do it, but when they, from Northern agitators, are spurred on to believe that they are the equal to the white man in every respect and should be just taken from savagery, and put on the same plane with the white man in every respect, that's not true. He shouldn't be... Even the dumbest farmer in the world knows that if he has white chickens and black chickens, that the black chickens do better if they're kept in one yard to themselves." (21)

Bull Connor announced that he was tired of listening to freedom songs and ordered the students to be taken back to Nashville. Salynn McCollum was released into her father's custody, was already on her wayback to New York. Walter McCollum told reporters: "I sent her to Nashville to get an education, not to get mixed up in this integration." Connor took them to the border town of Ardmore, Alabama, and advised them to take a train or bus back to Nashville. (22)

However, Zwerg, William E. Harbour, John Lewis, William Barbee, Catherine Burks, and others returned to Montgomery Bus Station. They were also joined by other Freedom Fighters including Susan Wilbur, Susan Herrmann, Bernard Lafayette, Paul Brooks, Allen Cason and Frederick Leonard. The Riders were prepared to spend the night at the terminal. Lewis commented: "We could see them through the glass doors and streetside windows, gestering at us and shouting. Every now and then a rock or a brick would crash through one of the windows near the ceiling. The police brought in dogs and we could see them outside, pulling at their leashes to keep the crowd back." (23)

and Bernard Lafayette at the Birmingham Greyhound bus station on May 19th, 1961.

A group of white men armed with lead pipes and baseball bats. Lewis later recalled: "Out of nowhere, from every direction, came people. White people. Men, women, and children. Dozens of them. Hundreds of them. Out of alleys, out of side seats, around the corners of office buildings, they emerged from everywhere, from all directions, all at once, as if they had been let out of a gate... They carried every makeshift weapon imaginable. Baseball bats, wooden boards, bricks, chains, tire irons, pipes, even garden tools - hoes and rakes. One group had woman in front, their faces twisted in anger, screaming." (24)

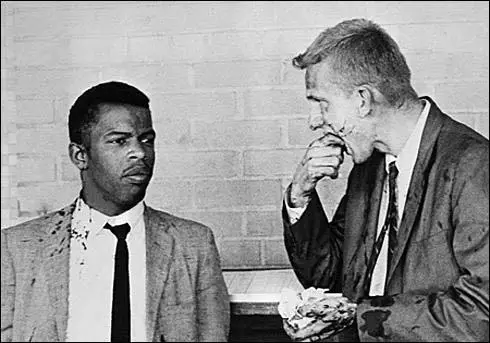

Zwerg, who departed the bus first, was a focal point because he was white. He was viewed as a “traitor” and a “turncoat.” Bruised and battered, his teeth were loosened, he suffered swollen and black eyes. Blood streamed down his face and onto his polyester-blend suit. Because he wore contact lenses that day, the blunt-force trauma from being hit by metal objects dislodged his contacts, injuring his eyes. Two of his vertebrae were broken. (25)

Frederick Leonard commented that as Zwerg was a white man he was a particular target for their anger. "It was like those people in the mob were possessed. They couldn't believe that there was a white man who would help us... It's like they didn't see the rest of us for about thirty seconds. They didn't see us at all." (26) Klansmen kicked Zwerg in the back before smashing him in the head with his own suitcase. Lucretia R. Collins recalled: "Some men held him while white women clawed his face with their nails. And they held up their little children - children who couldn't have been more than a couple of years old - to claw his face. I had to turn my head because I just couldn't watch it." (27)

One man stopped and clamped Zwerg’s head between his knees so others could beat him. The attackers knocked his teeth out and showed no signs of stopping, until a black man stepped in and ultimately saved his life. Zwerg recalls, "There was nothing particularly heroic in what I did. If you want to talk about heroism, consider the black man who probably saved my life. This man in coveralls, just off of work, happened to walk by as my beating was going on and said 'Stop beating that kid. If you want to beat someone, beat me.' And they did. He was still unconscious when I left the hospital. I don't know if he lived or died." (28)

Susan Herrmann later recalled: "The mob kept closing in and starting yelling 'Get 'em! Get 'em!'. They picked up Jim Zwerg of Beloit College in Wisconsin, the only white boy in our group, and threw him on the ground. They kicked him unconscious. Still, we didn't fight back. But we didn't believe in running either. I saw some men hold boys, who were nearly unconscious, while white women hit them with purses. The white women were yelling 'Kill them!' and other nasty shouts. The police came and said they would put us in protective custody. They acted like we were crazy. They just couldn't understand why we would be freedom riders. But even though they did not believe in what we were doing, they did protect us and in that sense upheld the law." (29)

John Lewis had been felled by a blow from a wooden Coco-Cola crate and was laying unconscious on the ground. James Zwerg and William Barbee, were also on the ground. Barbee was being stomped and kicked by a taunting swarm of rioters who were shouting, ‘Kill him! Kill him!’ The lives of Zwerg, Lewis and Barbee, were all saved by Floyd Mann the Director of the Alabama Department of Public Safety. "I received some confidential information that when they arrived at the bus station in Montgomery that the police had planned to take a holiday, there'd be no one present." Mann arrived to find the mob trying to kill the Freedom Riders: "Those freedom riders, some of them were being beaten with baseball bats... I just put my pistol to the head of one or two of those folks who was using baseball bats and told them unless they stopped immediately, they was going to be hurt. And it did stop immediately." (30)

Attempts were made by journalists sent by newspapers from national newspapers to cover the Freedom Riders, to get the men to hospital. Police Commissioner L. B. Sullivan told inquiring reporters that all the ambulances for whites were out of service with breakdowns. Zwerg was put into the backseat of a white cab, which was promptly abandoned by the driver. An African-American taxi driver volunteered to take Lewis and Barbee to a hospital, but the segregation laws forced Zwerg to remain behind. Eventually, the police allowed Zwerg to be taken by a black ambulance to a Catholic hospital, which agreed to receive him. (31)

Zwerg removes teeth knocked out by his attackers

The women Freedom Riders ran for safety. The women approached an African-American taxicab driver and asked him to take them to the First Baptist Church. However, he was unwilling to violate Jim Crow restrictions by taking any white women. He agreed to take the five African-Americans, but the two white women, Susan Wilbur and Susan Herrmann, were left on the curb. They were now attacked by the white mob. (32)

John Seigenthaler, who had been sent by Attorney General Robert Kennedy to negotiate with Governor John Patterson of Alabama, tried to drive into the mob to save a young woman who was being attacked, According to Raymond Arsenault, the author of Freedom Riders (2006): "Suddenly, two rough-looking men dressed in overalls blocked his path to the car door, demanding to know who the hell he was. Seigenthaler replied that he was a federal agent and that they had better not challenge his authority. Before he could say any more, a third man struck him in the back of the head with a pipe. Unconscious, he fell to the pavement, where he was kicked in the ribs by other members of the mob." (33) The crowd "kicked his unconscious body halfway under the car." (34)

Robert Kennedy, called for a “cooling-off” period and a halt to the rides. The Freedom Riders refused to do this. Speaking from his hospital bed, James Zwerg, assured reporters that "these beatings cannot deter us from our purpose. We are not martyrs or publicity-seekers. We want only equality and justice, and we will get it. We will continue our journey one way or another. We are prepared to die." (35) William Barbee echoed Zwerg's pledge: "As soon as we're recovered from this, we'll start again... We'll take all the South has to throw and still come back for more." Unfortunately, Barbee was unable to do this as a result of the beating he received he was paralyzed for life and had an early death, (36)

According to Ann Bausum: "Zwerg was denied prompt medical attention at the end of the riot on the pretext that no white ambulances were available for transport. He remained unconscious in a Montgomery hospital for two-and-a-half days after the beating and stayed hospitalized for a total of five days. Only later did doctors diagnose that his injuries included a broken back." (37)

James Zwerg later commented: "There was noting particularly heroic in what I did. If you want to talk about heroism, consider the black man who probably saved my life. This man in coveralls, just off of work, happened to walk by as my beating was going on and said 'Stop beating that kid. If you want to beat someone, beat me.' And they did. He was still unconscious when I left the hospital. I don't know if he lived or died." (38) Zwerg added:"Segregation must be stopped. It must be broken down. Those of us on the Freedom Ride will continue.... We're dedicated to this, we'll take hitting, we'll take beating. We're willing to accept death. But we're going to keep coming until we can ride from anywhere in the South to any place else in the South without anybody making any comments, just as American citizens." (39)

Zwerg's activities had a major impact on his family: "My dad did have a mild coronary and my mother came close to having a nervous breakdown. One of the things that I have discovered since, after having had a chance to really talk with several of the others, is that almost all of us had some form of real emotional problems with family or personally, in one way or another. Some people had a really hard time - after having had such a tremendous support group and atmosphere of love - having to readapt... For years and years, I was never able to discuss it with my dad. He just... you could just see the blood pressure go up. I think my mother ultimately understood. I went through some psychotherapy when I was in seminary, just because of the anger that developed. Again, these people who loved me and taught me to love didn't love what I was doing when I put my life on the line. I had to wrestle with that and work it through." (40)

After talking to Martin Luther King, Zwerg decided to enroll at Garrett Theological Seminary, a graduate school of theology of the United Methodist Church in Evanston. Zwerg was ordained a minister and served in three rural Wisconsin communities. Zwerg's parents had difficulty understanding their son's dedication to the cause of Civil Rights, and it took years to heal their relationship with him. After marrying Carrie he had three children. He changed his career several times, including charity organization work and employment in community relations at IBM. (41)

James Zwerg retired in 1993 after which the couple built a cabin in Ramah, New Mexico, about 135 miles west of Albuquerque. "He feeds the deer that wander nearby without fear. The grocery store is 50 miles away. Zwerg lives the calm, retired life after a versatile career as a minister and various positions in community relations and with charity organizations." (42)

Primary Sources

(1) World Heritage Encyclopedia (2002)

Zwerg was born in Appleton, Wisconsin, where he lived with his parents and older brother, Charles. His father was a dentist who provided free dental care to the poor on one day per month. Zwerg was very involved in school and took part in the student post in high school.

Zwerg was also very active in the Christian church, where he attended services regularly. Through the church, he became exposed to the belief in civil equality. He was taught that all men are created equal, no matter what color they are.

Zwerg attended activist group focused on nonviolent direct action. Zwerg joined SNCC and suggested that the group attend a movie. SNCC members explained to Zwerg that Nashville theaters were segregated. Zwerg began attending SNCC nonviolence workshops, often playing the angry bigot in role-play. His first test was to buy two movie tickets and try to walk in with a black man.When trying to enter the theater on February 21, 1961, Zwerg was hit with a monkey wrench and knocked unconscious.

In 1961, the Freedom Rides. The first departed from Washington, D.C. and involved 13 black and white riders who rode into the South challenging white only lunch counters and restaurants. When they reached Anniston, Alabama one of the busses was ambushed and attacked. Meanwhile, at a SNCC meeting in Tennessee, Lewis, Zwerg and 11 other volunteers decided to be reinforcements. Zwerg was the only white male in the group. Although scared for his life, Zwerg never had second thoughts. He recalled, "My faith was never so strong as during that time. I knew I was doing what I should be doing."

The group traveled by bus to Birmingham, where Zwerg was first arrested for not moving to the back of the bus with his black seating companion, Paul Brooks. Three days later, the riders regrouped and headed to Montgomery. At first the terminal there was quiet and eerie, but the scene turned into an ambush, with the riders attacked from all directions. Zwerg’s suitcase was grabbed and smashed into his face until he hit the ground, and others beat him repeatedly. One man stopped and clamped Zwerg’s head between his knees so others could beat him. The attackers knocked his teeth out and showed no signs of stopping, until a black man stepped in and ultimately saved his life. Zwerg recalls, "There was nothing particularly heroic in what I did. If you want to talk about heroism, consider the black man who probably saved my life. This man in coveralls, just off of work, happened to walk by as my beating was going on and said 'Stop beating that kid. If you want to beat someone, beat me.' And they did. He was still unconscious when I left the hospital. I don't know if he lived or died."

Zwerg was denied prompt medical attention because there were no white ambulances available. He remained unconscious for two days and stayed in the hospital for five days. His post-riot photos were published in many newspapers and magazines across the country. After his beating, Zwerg claimed he had had an incredible religious experience and God helped him to not fight back. In a 2013 interview recalling the incident, he said, "In that instant, I had the most incredible religious experience of my life. I felt a presence with me. A peace. Calmness. It was just like I was surrounded by kindness, love. I knew in that instance that whether I lived or died, I would be OK." In a famous moving speech from his hospital room, Zwerg stated, "Segregation must be stopped. It must be broken down. Those of us on the Freedom Ride will continue.... We're dedicated to this, we'll take hitting, we'll take beating. We're willing to accept death. But we're going to keep coming until we can ride from anywhere in the South to any place else in the South without anybody making any comments, just as American citizens."

Zwerg retired in 1993 after which the couple built a cabin in rural New Mexico about 50 miles (80 km) from the nearest grocery store. He has commented that his work in the ministry will always be with him.

(2) Gregory Clay, Jim Zwerg (26th October, 2016)

In the early 1960s, Fisk shared a student exchange program with Beloit College in Beloit, Wisconsin. Zwerg, a sociology major, arrived that January as a participant for the new semester. However, by the time he left Nashville, Zwerg’s photo became a poignant and horrific symbol of the civil rights movement.

Like a pledge joining a fraternity, Zwerg found himself a member of the Freedom Riders, a kinship of mostly black college men and women who valiantly tried to desegregate interstate bus travel and terminals in the South.

The Freedom Riders movement was formed to pressure the federal government to vigorously enforce the Supreme Court decision from the 1960 Boynton v. Virginia ruling that stated segregated interstate bus travel was unconstitutional.

During a Freedom Ride trip to Montgomery, Alabama, Zwerg was brutally beaten by a mob of violent white segregationists. Photos of his blood-spattered face as he lay in a hospital bed were published in newspapers across the country.

The picture made the front page of the Montgomery Advertiser. Video of him at the hospital, with that edition of the Advertiser newspaper atop his chest while he spoke to the media, was aired on national television news. In today’s lexicon, one James Zwerg from Appleton, Wisconsin, went “viral.”

He was a tall, white guy with short light brown hair from the North who ended up bonding with a determined black-dominated movement bent on changing the old Jim Crow customs of the segregated South. His father was a dentist, his mother an English teacher; they taught him to honor the Christian faith and not to mistreat people based on race.

In 1961, coincidentally the year President Barack Obama was born, Zwerg experienced life-altering events. While he was on that train, peering through the window at the countryside and eating a “very dry hamburger” as he headed to Nashville, Zwerg had no idea he soon would become a prominent social activist as part of a revolution of civil disobedience...

Zwerg had never been in a classroom with a black student from grades 1 through 12 in Wisconsin, though he had interacted with black kids from Milwaukee during Boy Scouts functions. At Beloit, one of his roommates was black, an experience that opened his eyes to racial inequities. That’s when he decided to walk in someone else’s shoes.

“My main reason for going to Fisk,” Zwerg said, “was that it gave me an opportunity to mirror the experiences of my black roommate at Beloit. Fisk was my first time being a minority. I wanted to know how I would be treated. It was a self-awareness and self-growth kind of thing.”

Zwerg’s indoctrination into the civil rights movement began when a couple of Fisk students suggested he attend nonviolence workshops produced by their revered mentor, James Lawson, then an activist-student at Vanderbilt University’s School of Divinity. One of Lawson’s tenets: “Don’t allow violence to stop a nonviolent movement.”

Appalled by the racial mistreatment he witnessed against black students in the segregated South, Zwerg was eager to make a difference.

Zwerg spoke of how in the 1960s, demonstrators and marchers contributed to the cause in a variety of ways - from disseminating newsletters about the movement to assisting senior citizens to beautifying communities on a grassroots level. The activists, many of them college students like Lawson, represented the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights organization headed by James Farmer that sponsored the Freedom Rides.

And Zwerg spoke of the day he met John Lewis, one of CORE’s young leaders. First, they both had hair back then. Lewis was based in Nashville at the time, attending seminary school at American Baptist Theological Seminary before earning a religion and philosophy degree at Fisk. The two met in 1961 when Zwerg and a group of black and white college students tried to desegregate a movie theater in downtown Nashville.

As part of the fashion of the 1960s civil rights movement, the men wore suits at the theater; the women wore dresses. That was by design. “One of the reasons why white people said they didn’t want to sit beside us wasn’t because we were black,” Bernard Lafayette, a black Freedom Rider, now 76, told The Undefeated. “They said it was because we were ‘dirty.’ So we put on what we called our ‘Sunday-go-to-meeting’ clothes."

“You had more dynamic members, like Jim Bevel, Diane Nash, Angie Butler, Bernard Lafayette and Joe Carter,” Zwerg recalled. “Some people were much more vocal than John. But when John spoke, he had everyone’s attention. He was the voice of reason. He had a deep faith, an absolute commitment to nonviolence. I remember he told me if I wanted to talk to him further, meet him at church.”

The Freedom Riders were greeted by angry white folk and Ku Klux Klan members armed with bricks, baseball bats, metal tools, chains and pipes. Zwerg, who departed the bus first, was a focal point because he was white. He was viewed as a “nigger-lover,” a “traitor” and a “turncoat.” Bruised and battered, his teeth were loosened, he suffered swollen and black eyes. Blood streamed down his face and onto his polyester-blend suit. Because he wore contact lenses that day, the blunt-force trauma from being hit by metal objects dislodged his contacts, injuring his eyes. Two of his vertebrae were broken.

“I’m the one who told him that he was knocked over the railings five times at the Greyhound bus station,” said Lafayette, a Fisk graduate who now works as an international training instructor of techniques in nonviolence and conflict resolution. “They knocked him over the rail, picked him up and knocked him over the other side. Back and forth. Punching him with their fists over and over. He was unconscious. He didn’t even know what was going on. He was lucky to live.”

Photos of the bloodied Zwerg appeared in such national magazines as Time and Life. “I just happened to get my picture taken,” Zwerg said, “after getting beat up. A lot of people got beaten up that day.”

While lying in bed at St. Jude’s Catholic Hospital, Zwerg told the television media, “We will take hitting and we will take beatings.”

Zwerg and his wife, Carrie, live in a cabin in a virtual wilderness in Ramah, New Mexico, about 135 miles west of Albuquerque. He feeds the deer that wander nearby without fear. The grocery store is 50 miles away. Zwerg lives the calm, retired life after a versatile career as a minister and various positions in community relations and with charity organizations.

(3) Ann Bausum, James Zwerg Recalls His Freedom Ride (1988)

When news of Zwerg's efforts reached Beloit College, students and faculty responded by drafting resolutions of support for his participation. Copies were circulated on campus and sent to the president of the United States and the governor of Alabama, among others.

Zwerg's experience deepened his commitment to religion, which led him to Garrett Theological Seminary, Evanston, Ill., and service as a minister in the United Church of Christ. He cites the Reverend Martin Luther King with helping him decide to enter the ministry during a half-hour meeting together when Zwerg was honored in 1961 with a "Freedom Award" by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Even though Zwerg ultimately changed his career, he comments that "the ministry will never be out of me entirely."

His experience also left Zwerg with an unswerving commitment to non-violence. "I couldn't have served in the military after that," notes Zwerg, for example.

Zwerg's parents had difficulty understanding their son's dedication to the cause of Civil Rights, and according to Zwerg, it took years to heal their relationship with him.

The father of three children, Zwerg believes that "if my son or daughter had that commitment, I'd say 'God Bless.'" He adds, though, "I would worry. It would be tough."

Zwerg was reunited with Lewis and another Civil Rights friend several years ago while on a business trip to Atlanta. He was brought up to date on many others by viewing the Public Broadcasting System's Civil Rights documentary, "Eyes on the Prize," which he praises for its accuracy and impact.

Zwerg revisited Montgomery on the 25th anniversary of the Freedom Rides to take part in a Canadian Broadcasting Company documentary on them. At one point during filming, Zwerg was riding a bus into Montgomery. Although the film crew did not notice it, Zwerg was immediately struck by the fact that the driver of the bus was black and the passenger directly behind him was a young black man. Zwerg started a conversation with the black passenger and learned that he had never heard of the Freedom Riders or their reception in Montgomery.

"Here was a young 16-year-old riding to Montgomery without a thought in his head about the Freedom Rides. Riding that bus was the most natural thing in the world for him to do." Zwerg asks rhetorically: "Did we accomplish something with our rides? You bet we did!"

(4) Interview with James Zwerg in The People's Century (1995)

Q: You got involved in the Freedom Rides...

Zwerg: Well, we got word on the CORE Freedom Ride, and we knew that John Lewis, a member of our organization, was going to be involved in it. We got word of the burning in Aniston... we had a meeting long into the night as soon as we heard about it. The feeling was that if we let those perpetrators of violence believe that people would stop if they were violent enough, then we would take serious steps backwards. Right away the feeling was that we needed to ride. We called Dr. King, we called James Farmer. There was an awareness that our phones were being tapped, so the feeling was that they knew what we were about to do. Our plan was different from CORE's. Whereas they chartered their buses, we were just going to get tickets and get on the bus. We felt that was even more important -- to buy a ticket just like any other traveler. We weren't getting a special bus, we were just going to get on the bus.

It was decided that we would send twelve people. I was one of 18 that volunteered to go. I've been asked why I volunteered to go... I would have to say, at that moment, it wasn't even a question. It was the right thing for me to do. I never second-guessed it.

Q: How did you prepare?

Zwerg: After we had talked it out and I was one of those chosen to go, I went back to my room and spent a lot of time reading the bible and praying. Because of what had happened in Birmingham and in Aniston, because our phones were tapped... none of us honestly expected to live through this. I called my mother and I explained to her what I was going to be doing. My mother's comment was that this would kill my father - and he had a heart condition - and she basically hung up on me. That was very hard because these were the two people who taught me to love and when I was trying to live love, they didn't understand. Now that I'm a parent and a grandparent I can understand where they were coming from a bit more. I wrote them a letter to be mailed if I died. We had a little time to pack a suitcase and then we met to go down to the bus.

Q: What was the journey like?

Zwerg: We just got the tickets and got on the bus. I was going to sit in the front of the bus with Paul Brooks. Paul sat by the window; I sat by the aisle. The rest of the blacks and one white girl, Celine McMullen, were going to sit in the back.

It was an uneventful ride until we got to the Birmingham city limits. We were pulled over by the police... They came on the bus and said, "This is a Freedom Rider bus, who's on here from Nashville? And the bus driver pointed to Paul and myself. They came up and really started badgering Paul, you know, "Get up... why aren't you in the back of the bus?" And he said he was very comfortable where he was. So they placed him under arrest. And they asked me to move so they could get to him... and I said, "I'm very comfortable where I am too."

We were both placed under arrest, taken off the bus, seated in the squad car for I don' t know how long. Finally they took us to Birmingham Jail and fingerprinted us. They put me in solitary for a little while. Then they put me in with a fellow who was a felon. I mean, I'm in my suit and tie and I've got my pocket bible with me. I think he thought I was some clergyman making calls. Ultimately they threw me in a drunk tank, with about twenty guys in various states of inebriation, and announced in no uncertain terms that I was a Freedom Rider. Here he is, boys, have at him! I didn't know what was going to happen and I kind of said, "How do you guys feel about this? Do you know what they're talking about?" And they started asking me some questions.

One of the things we agreed on is that if you were jailed, number one, you go on a hunger strike, because in our minds we were jailed illegally. You don't cop a plea, you don't pay the bail and jump. You stay. But here I was. One single white guy. And I didn't know what had happened to Paul. I didn't know what had happened to the rest of the people on the bus. I began to see the state that some of drunks were in, and I tried to get some towels and clean up the guys who were sick. I just got talking to some of them and none of them ever laid a hand on me. Basically, we talked about what I believed and what they believed.

I discovered that since the South was predominately Baptist, Catholics were kind of looked down on at the time. Surprisingly, 19 of the 20 guys in the drunk tank were Catholics! So we kind of had something more in common than they realized.

Q: Were you able to contact the other riders?

Zwerg: Frequently, music was the way we communicated in jail. Keep Your Eyes on the Prize, Hold On has beautifully lyrics...

Paul and Sylus bound in jail

got nobody to go our bail

Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on.

I sang it for my cellmates and they liked it. So I got probably ten of these guys singing with me. They had taken all the rest of the people on the bus into protective custody, and I had heard them singing. Now they could hear this group singing, and know I was okay.

We still had to go to mess even though you didn't eat. One day a fellow came in who was quite sick and I smuggled a sandwich back to the cell for him. I didn't know that act was punishable by three months in jail. But by giving him a sandwich -- suddenly I was a good guy and nobody was going to lay a hand on me. So the two and a half days that we were in jail were fine. We got to know each other. We talked. When I was in court I was really pleased that a number of these guys came over to me and said, "Jim, we really don't agree with you, but we wish you all the best."

Q: What were your thoughts as you rode on the bus?

Zwerg: As we were going from Birmingham to Montgomery, we'd look out the windows and we were kind of overwhelmed with the show of force - police cars with sub-machine guns attached to the backseats, planes going overhead... We had a real entourage accompanying us. Then, as we hit the city limits, it all just disappeared. As we pulled into the bus station a squad car pulled out - a police squad car. The police later said they knew nothing about our coming, and they did not arrive until after 20 minutes of beatings had taken place. Later we discovered that the instigator of the violence was a police sergeant who took a day off and was a member of the Klan. They knew we were coming. It was a set-up.

Q: You were attacked when you arrived at the bus station?

Zwerg: The idea had been that cars from the community would meet us. We'd disperse into these cars, get out into the community, and avoid the possibility of violence. And the next morning we were to come back to the station and I would use the colored services and they would go to some of the white services -- the restroom, the water fountain, etc. And then you'd get on the bus and go to the next city. It was meant to be as non-violent as possible, to avoid confrontation as much as possible.

Well, before we got off the bus, we looked out and saw the crowd. You could see things in their hands -- hammers, chains, pipes... there was some conversation about it. As we got off the bus, there was some anxiety. We started looking for the cars. But the mob had surrounded the bus station so there was no way cars could get in and we realized at that moment that we were going to get it.

There was a fellow, a reporter, with an old boom mike and he was panning the crowd. And that's when this heavy-set fellow in a white T-shirt... he had a cigar as I remember... came out and grabbed the mike and jumped on it... just smashed it... basically telling the press, "Back off! You are not going to take any pictures of this. You better stay out or you're going to get it next." You could hear crowd yelling and of course a lot of them were, "Get the nigger-lover!" I was the only white guy there.

I bowed my head and asked God to give me the strength and love that I would need, that I put my life in his hands, and to forgive them. And I had the most wonderful religious experience. I felt a presence as close to me as breath itself, if you will, that gave me peace knowing that whatever came, it was okay. Before I opened my eyes, I was grabbed. I was pulled over a railing and thrown to the ground. I remember trying to get up on all fours because you try to get back to your group.

One of the things that I alluded to earlier was the strength we got from one another. To this day I'm sure I'm not the most nonviolent person in the world, but the strength of those people with me gave me strength beyond my own capabilities. Just as when we would see someone else being beaten, our hearts went to them and our strength went to them.

Q: Were you hurt?

Zwerg: Traditionally a white man got picked out for the violence first. That gave the rest of the folks a chance to get away. I was told that several tried to get into the bus terminal. I was knocked to the ground. I remember being kicked in the spine and hearing my back crack, and the pain. I fell on my back and a foot came down on my face. The next thing I remember is waking up in the back of a vehicle and John Lewis handing me a rag to wipe my face. I passed out again and when I woke up I was in another moving vehicle with some very southern-sounding whites. I figured I'm off to get lynched. I had no idea who they were. Again, I went unconscious and I woke up in the hospital. I was informed that I had been unconscious for a day and a half. One of the nurses told me that another little crowd were going to try and lynch me. They had come within a half block of the hospital. She said that she knocked me out in case they did make it, so that I would not be aware of what was happening. I mean, those pictures that appeared in the magazines, the interview... I don't remember them at all. I do remember a class of students -- I think they were high school age, coming to visit me one time.

Q: What was your family's reaction to all this?

Zwerg: My dad did have a mild coronary and my mother came close to having a nervous breakdown. One of the things that I have discovered since, after having had a chance to really talk with several of the others, is that almost all of us had some form of real emotional problems with family or personally, in one way or another. Some people had a really hard time - after having had such a tremendous support group and atmosphere of love - having to readapt.

Others have encountered some medical problems, things like that. For years and years, I was never able to discuss it with my dad. He just... you could just see the blood pressure go up. I think my mother ultimately understood. I went through some psychotherapy when I was in seminary, just because of the anger that developed. Again, these people who loved me and taught me to love didn't love what I was doing when I put my life on the line. I had to wrestle with that and work it through.

(5) Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 (1988)

One of the men grabbed Zwerg's suitcase and smashed him in the face with it. Others slugged him to the ground, and when he was dazed beyond resistance, one man pinned Zwerg's head between his knees so that the others could take turns hitting him. As they steadily knocked out his teeth, and his face and chest were streaming blood, a few adults on the perimeter put their children on their shoulders to view the carnage.

(6) Tom Gjelten, White Supremacist Ideas Have Historical Roots In U.S. Christianity (1st July, 2020)

When a young Southern Baptist pastor named Alan Cross arrived in Montgomery, Alabama in January 2000, he knew it was where Martin Luther King, Jr. had his first church and where Rosa Parks launched her famous bus boycott, but he didn't know some other details of the city's role in civil rights history.

The more he learned, the more troubled he became by one event in particular: the savage attack in May 1961 on a busload of Black and white "Freedom Riders" who had traveled defiantly together to Montgomery in a challenge to segregation. Over the next 15 years, Cross, who is white, would regularly take people to the old Greyhound depot in Montgomery to highlight what happened that spring day.

"They pull in right here, on the side," Cross says, standing in front of the depot. "And it was quiet when they got here. But then once they start getting off the bus, around 500 people come out – men, women, and children. Men were holding the Freedom Riders back, and the women were hitting them with their purses and holding their children up to claw their faces." Some of the men carried lead pipes and baseball bats. Two of the Freedom Riders, the civil rights activist John Lewis and a white ally, James Zwerg, were beaten unconscious.

Though he had grown up in Mississippi and was familiar with the history of racial conflict in the South, Cross was horrified by the story of the 1961 attack on the Freedom Riders. Montgomery was known as a city of churches. Fresh out of seminary, Cross had come there to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ.

"Why didn't white Christians show up?" he recalls wondering.

To his dismay, Cross learned that many of the people in the white mob were themselves regular church-goers. In the years that followed, he made it part of his ministry to educate his fellow Christians about the attack and prompt them to reflect on its meaning.

"You think about the South being Christian, but this wasn't Christianity," Cross says. "So what happened here in the white church? How did we get to that point?" It's a question he explored in his 2014 book, When Heaven and Earth Collide: Racism, Southern Evangelicals, and the Better Way of Jesus.

The answer to the question lies partly in U.S. history, beginning in the days of slavery and Jim Crow segregation, but not ending there. Elements of racist ideology have long been present in white Christianity in the United States.

Less than three weeks after the 1961 attack on the Freedom Riders, Montgomery's most prominent pastor, Henry Lyon, Jr., gave a fiery speech before the local white Citizens' Council, denouncing the civil rights protesters and the cause for which they were beaten — from a "Christian" perspective.

"Ladies and gentlemen, for 15 years I have had the privilege of being pastor of a white Baptist church in this city," Lyon said. "If we stand 100 years from now, it will still be a white church. I am a believer in a separation of the races, and I am none the less a Christian." The crowd applauded.

"If you want to get in a fight with the one that started separation of the races, then you come face to face with your God," he declared. "The difference in color, the difference in our body, our minds, our life, our mission upon the face of this earth, is God given."

Lyon saw himself as a devout Bible believer, and he was far from an extremist in the Southern Baptist world. A former president of the Alabama Baptist Convention, his Montgomery church had more than 3000 members.

How respected people of God could openly promote racist views was a question that would trouble many southerners in the years that followed. Among them was a young woman growing up in east Texas in the 1970s, Carolyn Renée Dupont. The girl's grandmother took her regularly to church, made her listen to sermons on the radio, and gave her a quarter for every Bible verse she memorized. But the grandmother believed just as deeply in the superiority of the white race.

"I asked her about that once," Dupont recalls, "and she said, 'I just don't believe Blacks should be treated the same as whites.'" Dupont, now a historian at Eastern Kentucky University, says the experience with her grandmother spurred her to focus her research on the racial views of southern white evangelicals. "I wanted to understand what seemed like a central riddle about the South," she says. "The part of the country that was the most fervent about religious faith was also the one that practiced white supremacy most enthusiastically." It was the same question that bothered Alan Cross as a young pastor in Montgomery.

At an earlier point in American history, some Christian theologians went so far as to argue that the enslavement of human beings was justifiable from a biblical point of view. James Henley Thornwell, a Harvard-educated scholar who committed huge sections of the Bible to memory, regularly defended slavery and promoted white supremacy from his pulpit at the First Presbyterian Church in Columbia, South Carolina, where he was the senior pastor in the years leading up to the Civil War.

"As long as that [African] race, in its comparative degradation, co-exists side by side with the white," Thornwell declared in a famous 1861 sermon, "bondage is its normal condition." Thornwell was himself a slave owner, and in his public pronouncements he told fellow Christians they need not feel guilty about enslaving other human beings.

"The relation of master and slave stands on the same foot with the other relations of life," Thornwell insisted. "In itself, it is not inconsistent with the will of God. It is not sinful." The Christian scriptures, Thornwell said, "not only fail to condemn; they as distinctly sanction slavery as any other social condition of man."

Among the New Testament verses Thornwell could cite was the Apostle Paul's letter to the Ephesians where he writes, "Slaves, obey your human masters, with fear and trembling and sincerity of heart." (Biblical scholars now discount the relevance of the passage to a consideration of chattel slavery.)

Thornwell's reassurance was immensely important to all those who had a stake in the existing economic and political system in the South. In justifying slavery, he was speaking not just as a theologian but as a southern patriot. In the First Presbyterian cemetery, Thornwell's name appears prominently on a monument to church members who served the Confederate cause in the Civil War.

'Slavery, in the minds of many, was necessary for the South to thrive," says Bobby Donaldson, director of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research at the University of South Carolina. "So Thornwell used his pulpit to defend the South against charges by the North, by abolitionists. ... He provided the intellectual defenses that many slaveholders needed."

Thornwell's First Presbyterian congregation included slaveowners and businessmen and other members of the political and economic elite in Columbia, and as their pastor he represented their interests. A belief in white supremacy was a foundational part of southern culture, which is one reason some otherwise devout Christians have failed to challenge it.

Pastor Henry Lyon, Jr.'s opening prayer before the white Citizens' Council meeting in Montgomery included words starkly reminiscent of the Civil War era. "We stand on the sacred soil of Alabama in the Cradle of the Confederacy of our beloved Southland," he said. "Help us to realize with all of the fervency of our heart and mind that every inch of ground we stand on tonight is sacred and honorable."

A fear that their regional culture was at risk lay behind much of the opposition to the civil rights movement among southern Christians. Alan Cross, the Montgomery pastor who was dismayed by what he learned of the attack on the Freedom Riders, ultimately decided that the best explanation for the involvement of Christians in the incident was that they were acting on the basis of their perceived self-interest.

"People try to protect their way of life," he says. "You know, 'What's best for me and my family?' You even begin to use God as a means to an end. It makes a lot of sense to people, and they're, like, 'Well, that's what everybody does.'"

A "don't-rock-the-boat" philosophy can have a powerful appeal among people who are unnerved by the prospect of social change, and church leaders may feel powerless to counter it.

In 1965, Henry Lyon, Jr.'s more moderate son, Henry Lyon III, was called to lead an all-white Baptist church in Selma, Alabama. He arrived in the city two months after the "Bloody Sunday" confrontation on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, when more than 2000 civil rights marchers were savagely attacked by Alabama state troopers and local lawmen. The younger Lyon, who died in 2018, never adopted his father's bigoted rhetoric, and his wife Sara Jane Lyon says he was personally willing to open his church to African Americans. During the 21 years Lyon served as the church's pastor, however, his congregation never accepted Black members, apparently because he did not feel free to press the issue.

"Selma wasn't ready for it," Sara Jane Lyon told NPR in an interview. "He knew it would accomplish nothing if he upset everybody and pushed, you know, to integrate the church."

Churches operate within a cultural context. By challenging local customs and perspectives, pastors may alienate the white economic and political players who serve as their deacons, elders, Sunday School teachers, and financial supporters.

In his sermons, Mrs. Lyon recalled, her husband would tell his congregation, "I have not come here to change your heart. There's no way I can do that. ... Only the Lord can change your heart." Asked whether her husband ever discussed racial justice as a pastor, Lyon said, "That was not his style of preaching. He didn't get up and talk about local issues. He preached the Word of God."

After leaving Selma, the Lyons relocated to Montgomery and joined the First Baptist Church there. With about 5000 members, the church has a central place in civic life. The congregation is almost entirely white, but it's not because of a deliberate policy. The pastor, Jay Wolf, says he welcomes everyone.

"When I came to know the Lord, I became color-blind," Wolf says. When some visitors asked Wolf how many African Americans attended his church, he said he had "no idea."

"I don't know how many white members we have," Wolf told NPR. "Like, does it make any difference? I just know that we have people, crafted in the image of God. I am completely resistant to this idea of breaking things down on a demographic basis. We are the body of Christ, and we need Jesus, and that's all I need to know."

On the other side of Montgomery, where African American residents are concentrated, Pastor Terence Jones also preaches about needing Jesus, though with a message attuned to a multi-racial congregation. The son of a Black Southern Baptist preacher, Jones thinks the Christian church is partly to blame for America "dropping the ball," in his words, on race issues.

"The message of Jesus is a unifying message," Jones says. "According to Ephesians 2, he tears down 'every dividing wall of hostility' through his death on the cross. I think we've done a poor job of showing the world that, because we've been so segregated."

Jones argues that Christians need to focus on racism far more seriously.

"When people get shot, when our president says something racially charged, people get pushed into their corners, and they don't wrestle with what does this mean for me as a minority, what does this mean for me as a white person, but also, what does this mean for me as a follower of Jesus?"

At the time of the civil rights movement, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. argued that church leaders needed to take a broad view of their mission and accept responsibility for addressing social inequity. In his 1963 "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," written in longhand from his jail cell, King lamented the failure of "white churchmen" to stand up for racial justice when it meant challenging the local power structure.

"So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound," King wrote. "So often it is an arch-defender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church's silent—and often even vocal—sanction of things as they are."

Some white Christian leaders have even provided moral and theological reasoning for their reluctance to challenge the existing system. Evangelicals in particular generally prioritize an individual's own salvation experience over social concerns. The primary mission of the church in this view is to win souls for Christ. Working for racial justice, in contrast, may be seen as a "political" issue.

"In that configuration, immorality only lives in the individual person," says Carolyn Renée Dupont, the religion historian who grew up in Texas. "There's no conception of systemic injustice and systemic sin."

Civil rights activists who cited the Bible in support of their cause were often dismissed as "a bunch of theological liberals," Dupont says. "And then it becomes an argument about who really believes the Bible. If Christianity is really about individual salvation, and the mission of the church is to win the lost, then [it is said that] these people who are telling us we need to get involved in the civil rights movement are just trying to lead us astray."

The rejection of a "social gospel" remains popular among those conservative evangelicals today who see advocating for Black Lives Matter or immigrant rights as political activities. It is an argument with roots extending back to the theology of James Henley Thornwell and like-minded religion scholars of the 19th century.

"What, then, is the Church?" Thornwell asked in his 1851 Report on Slavery. "It is not, as we fear too many regard it, a moral institute of universal good whose business it is to wage war upon every form of human ill, whether social, civil, political or moral."

Such pronouncements have made Thornwell popular among "orthodox" Christian theologians who rebel against liberal interpretations of the church's mission in the modern world. Once his pronouncements on slavery and race are disregarded, Thornwell's theological views still resonate.

One of the buildings on the grounds of his former church in South Carolina is Thornwell Hall. Until it closed due to coronavirus concerns, the building was used for children's education. The First Presbyterian ministerial staff have not been overly concerned that by thus honoring Thornwell, they may be offending potential African American members.

"As far as I know, it has not kept people from our doors," says Gabe Fluhrer, an associate pastor at the church.

Fluhrer has studied Thornwell's writings, many of which are highly sophisticated, and he is dismayed that the theologian's views on slavery and race have made it more difficult for people to appreciate his broader biblical insight.

"If it were an impediment [to someone]," Fluhrer says, "I would love to speak to that person and say, 'Look, we need to condemn what is wrong with him, and we need to celebrate what is good.' He got a lot right on the scriptures and everything wrong when it comes to race."

Getting everything wrong with regard to race, however, can be an unforgivable failing for people whose life experience is shaped by racism.

For many years, African American worshipers were relegated to the First Presbyterian balcony. Church authorities later permitted them to have a church a few blocks away where they could worship separately, under the supervision of the First Presbyterian elders. It became known as Ladson Presbyterian, after one of the church's early pastors.

The church has only a few dozen active members these days, but the congregation is close, and the Sunday services are intimate and joyful gatherings. There is no longer any connection to the original church.

"I don't know anyone who goes to First Presbyterian," says Rosena Lucas, 88, a longtime Ladson member. "I've never had any interest [in attending]," she says.

Nor has Hemphill Pride, an elder in the Ladson congregation. "I see that church as a stranger, really," he says. For Pride and other Ladson members, the Thornwell connection still taints the parent church.