Salynn McCollum

Mary Salynn McCollum, the daughter of Hilda and Walter McCollum, was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma on 6th April 1940. The family moved to Amherst, New York, and in 1948 she attended George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee. Her course of study focused on instruction for intellectually and developmentally disabled children. (1)

Salynn McCollum: Civil Rights Activist

In 1960 McCollum became involved in the Nashville Non-Violent Movement, that was the local branch of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In February 1961 she became active in the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and eventually she was appointed as secretary to the Central Committee. (2)

Transport segregation continued in the Deep South, so that CORE began to develop strategies to bring it to an end. James Farmer became national director of CORE and in 1960 Genevieve Hughes was appointed as a field secretary. According to Raymond Arsenault: "During the late 1950s she (Hughes) became active in the local chapter of CORE, eventually helping to rejuvenate the chapter by co-ordinating a boycott of dime stores affiliated with chains resisting the sit-in movement in the South. Exhilarated by the boycott and increasingly alienated from the conservative complacency of Wall Street, she gravitated toward a commitment to full-time activism, accepting a CORE field secretary position in the fall of 1960. The first woman to serve on CORE's field staff, she made a lasting impression on everyone who met her." (3) Hughes was once asked why she had joined CORE she replied: "I figured Southern women should be represented to the South and the nation would realize all Southern people don't think alike." (4)

In February, 1961, CORE organised a conference in Kentucky where the organisation laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge the racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (5) John Lewis, a student at Nashville American Baptist Theological Seminary, commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." (6)

Freedom Rider

Salynn McCollum decided to volunteer to take part in the Freedom Rides. (7) The first bus left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Members of CORE who travelled on the bus included John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes, James Farmer, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (8)

The second bus left on the 17th May. Salynn McCollum, missed the bus, although after a frantic seventy-mile car chase she managed to join the other Riders when the bus stopped at Pulaski, a small town in south central Tennessee. (9) Other passengers included William Barbee, William E. Harbour, Susan Herrmann, Lafayette Bernard, Susan Wilbur, James Zwerg, Frederick Leonard, Lucretia Collins, Paul Brooks and Catherine Burks, Susan Herrmann, 20, a student at Fisk University, Nashville, majoring in psychology, later recalled: "We were all prepared to die - and for a while Saturday I thought all 21 of us would die at the hands of that mob in Montgomery. We did not fight back. We do not believe in violence. We were freedom riders... trying to ride in buses through Alabama to New Orleans to help the cause of true freedom for all the races." (10)

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, ordered the arrest of all the Freedom Riders when they arrived in the city. As the only white female, Salynn McCollum was placed in a special facility, and Collins and Burks were put in a cell with several other black women. All the men ended up in a dark and crowded cell that Lewis likened to a dungeon. "It had no mattresses or beds, nothing to sit on at all, just a concrete floor." Harbour and his cellmates adopted a strategy of Gandhian non-cooperation. Lewis added "We went on singing both to keep our spirits up and - to be honest - because we knew that neither Bull Conner nor his guards could stand it." (11)

William Pritchard, one of Birmingham's leading attorneys, claimed: "I have no doubt that the Negro basically knows that the best friend he's ever had in the world is the Southern white man. He'd do the most for him - always has and will continue to do it, but when they, from Northern agitators, are spurred on to believe that they are the equal to the white man in every respect and should be just taken from savagery, and put on the same plane with the white man in every respect, that's not true. He shouldn't be... Even the dumbest farmer in the world knows that if he has white chickens and black chickens, that the black chickens do better if they're kept in one yard to themselves." (12)

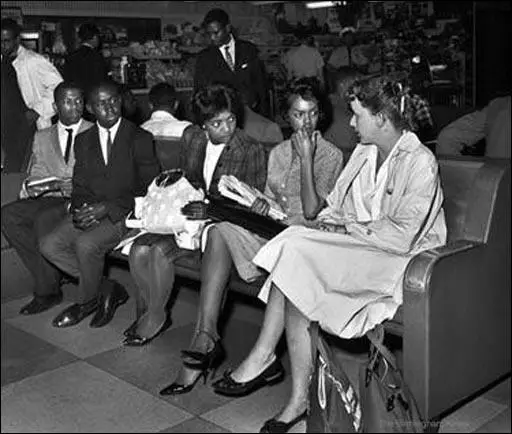

and Salynn McCollum on 17th May, 1961.

Bull Connor announced that he was tired of listening to freedom songs and ordered the students to be taken back to Nashville. Salynn McCollum was released into her father's custody, was already on her way back to New York. Walter McCollum told reporters: "I sent her to Nashville to get an education, not to get mixed up in this integration." Connor took them to the border town of Ardmore, Alabama, and advised them to take a train or bus back to Nashville. (13)

However, William E. Harbour, John Lewis, James Zwerg, William Barbee, Catherine Burks, and others returned to Montgomery Bus Station. They were also joined by other Freedom Fighters including Susan Wilbur, Susan Herrmann, Bernard Lafayette, Paul Brooks, Allen Cason and Frederick Leonard. The Riders were prepared to spend the night at the terminal. Lewis commented: "We could see them through the glass doors and street-side windows, gesturing at us and shouting. Every now and then a rock or a brick would crash through one of the windows near the ceiling. The police brought in dogs and we could see them outside, pulling at their leashes to keep the crowd back." (14)

Later Life

Despite the protests of her parents McCollum continued to be active in the civil rights movement and worked as a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field secretary in different locations in the Deep South. Even when McCollum left this work she continued to give talks on her experiences as a Freedom Rider. (15)

In 1965 McCollum took a job as a Day Care Center Director in Harlem. In the 1980s she moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she trained dogs and rode horses. In 2000, she moved to Tennessee where she lived with her sister, Rhonda McCollum and family, in Nunnelly. (16)

Mary Salynn McCollum died on 1st May, 2014.

Primary Sources

(1) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006)

Salynn McCollum, the only white female Rider, missed the bus, although after a frantic seventy-mile car chase she managed to join the other Riders when the bus stopped at Pulaski, a small town in south central Tennessee that had served as the birthplace of the original Ku Klux Klan in 1866. With McCollum safely on board, the bus crossed the Alabama line without incident by midmorning.

(2) James Farmer, interviewed by Howell Raines for his book, My Soul is Rested: Movement Days in the Deep South Remembered (1983)

I was impressed by the fact that most of the activity thus far had been of local people working on their local problems-- Greensborans sitting-in in Greensboro and Atlantans sitting-in in Atlanta - and the pressure of the opposition against having outsiders come was very, very great. If any outsiders came in... "Get that outside agitator." . . . I thought that this was going to limit the growth of the Movement.... We somehow had to cut across states lines and establish the position that we were entitled to act any place in the country, no matter where we hung our hat and called home, because it was our country.

We also felt that one of the weaknesses of the student sit-in movement of the South had been that as soon as arrested, the kids bailed out... This was not quite Gandhian and not the best tactic. A better tactic would be to remain in jail and to make the maintenance of segregation so expensive for the state and the city that they would hopefully come to the conclusion that they could no longer afford it. Fill up the jails, as Gandhi did in India, fill them to bursting if we had to. In other words, stay in without bail.

So those were the two things: cutting across state lines, putting the movement on wheels, so to speak, and remaining in jail, not only for its publicity value but for the financial pressure it would put upon the segregators. We decided that a good approach here would be to move away from restaurant lunch counters. That had been the Southern student sit-in movement, and anything we would do on that would be anticlimactic now. We would have to move into another area and so we decided to move into the transportation, interstate transportation...

So we, following the Gandhian technique, wrote to Washington. We wrote to the Justice Department, to the FBI, and to the President, and wrote to Greyhound Bus Company and Trailways Bus Company, and told them that on May first or May fourth - whatever the date was, I forget now - we were going to have a Freedom Ride. Blacks and whites were going to leave Washington, D.C., on Greyhound and Trailways, deliberately violating the segregated seating requirements and at each rest stop would violate the segregated use of facilities. And we would be nonviolent, absolutely nonviolent, throughout the campaign, and we would accept the consequences of our actions. This was a deliberate act of civil disobedience...

We got no reply from Justice. Bobby Kennedy (U.S. Attorney General) no reply. We got no reply from the FBI. We got no reply from the White House, from President Kennedy. We got no reply from Greyhound or Trailways. We got no replies...

We had some of the group of thirteen sit at a simulated counter asking for coffee. Somebody else refused them service, and then we'd have others come in as white hoodlums to beat 'em up and knock them off the counter and club 'em around and kick 'em in the ribs and stomp 'em, and they were quite realistic, I must say. I thought they bent over backwards to be realistic. I was aching all over. And then we'd go into a discussion as to how the roles were played, whether there was something that the Freedom Riders did that they shouldn't have done, said that they shouldn't have said, something that they didn't say or do that they should have, and so on. Then we'd reverse roles and play it over and over again and have lengthy discussions of it.

I felt, by the way, that by the time that group left Washington, they were prepared for anything, even death, and this was a possibility, and we knew it, when we got to the Deep South.

Through Virginia we had no problem. In fact they had heard we were coming, Greyhound and Trailways, and they had taken down the For Colored and For Whites signs, and we rode right through. Yep. The same was true in North Carolina. Signs had come down just the previous day, blacks told us. And so the letters in advance did something.

In South Carolina it was a different story.... John Lewis started into a white waiting room in some town in South Carolina... and there were several young white hoodlums, leather jackets, ducktail haircuts, standing there smoking, and they blocked the door and said, "You can't come in here." He said, "I have every right to enter this waiting room according to the Supreme Court of the United States in the Boynton case."

They said, "Shit on that." He tried to walk past, and they clubbed him, beat him, and knocked him down. One of the white Freedom Riders . . . Albert Bigelow, who had been a Navy captain during World War II, big, tall, strapping fellow, very impressive, from Connecticut - then stepped right between the hoodlums and John Lewis. Lewis had been absorbing more of the punishment. They then clubbed Bigelow and finally knocked him down, and that took some knocking because he was a pretty strapping fellow, and he didn't hit back at all. They knocked him down, and at this point police arrived and intervened. They didn't make any arrests. Intervened.

(3) James Lawson, The Southern Patriot (November, 1961)

We must recognize that we are merely in the prelude to revolution, the beginning, not the end, not even the middle. I do not wish to minimize the gains we have made thus far. But it would be well to recognize that we have been receiving concessions, not real changes. The sit-ins won concessions, not structural changes; the Freedom Rides won great concessions, but not real change.

There will be no revolution until we see Negro faces in all positions that help to mold public opinion, help to shape policy for America.

One federal judge in Mississippi will do more to bring revolution than sending 600 marshals to Alabama. We must never allow the President to substitute marshals for putting people into positions where they can affect public policy. . . .

Remember that the way to get this revolution off the ground is to forge the moral, spiritual and political pressure which the President, the nation and the world cannot ignore.