William E Harbour

William E. Harbour, the son of a cotton mill worker, and the oldest of eight children, was born in 1942. He was the first member of his family to go to college when he attended the Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State University. Harbour along with fellow students, William Barbee, Charles Butler, Catherine Burks, Lucretia R. Collins and Allen Cason joined Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and became involved in the struggle against segregation in the Deep South. (1)

Members of CORE were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. CORE became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America. (2)

CORE decided to campaign to bring an end to segregated seating in restaurants. In Greensboro, North Carolina, a small group of black students decided to take action themselves. On 1st February, 1960, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, Joseph McNeil and Ezell Blair, started a student sit-in at the restaurant of their local Woolworth's store which had a policy of not serving black people. In the days that followed they were joined by other black students until they occupied all the seats in the restaurant. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of Martin Luther King they did not hit back. McCain later recalled: "On the day that I sat at that counter I had the most tremendous feeling of elation and celebration. I felt that in this life nothing else mattered. I felt like one of those wise men who sits cross-legged and cross-armed and has reached a natural high." (3)

Segregated Seating Campaign

CORE began a campaign against segregated seating in Nashville in February 1960. They achieved their first success when Diane Nash, Matthew Walker Jr., Peggy Alexander and Stanley Hemphill became the first blacks to eat lunch at the Post House Restaurant in the Nashville Greyhound Bus Terminal. It was the first Southern city where blacks and whites could sit together for lunch. As one civil rights activist pointed out: “It was the first time anyone in a leadership position who could make a difference, made a difference." (4)

Sit-ins continued through the following year, and on 6th February, 1961. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leaders went to jail after supporting the “Rock Hill Nine” or “Friendship Nine,” nine students incarcerated after a lunch counter sit-in in Rock Hill, South Carolina. The students would not pay bail after their arrests because they believed paying fines supported the immoral practice of segregation. The unofficial motto of student activists was “jail, not bail.” Eventually over a 100 served a month in prison. (5) Harbour met John Lewis, a senior figure in CORE during these protests. (6)

In February, 1961, CORE organised a conference in Kentucky where the organisation laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge the racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (7) As one black volunteer commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." (8)

Freedom Rides

The first bus left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Members of CORE who travelled on the bus included John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes, James Farmer, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (9)

The Freedom Riders were split between two buses. They traveled in integrated seating and visited "white only" restaurants. Governor John Malcolm Patterson of Alabama who had been swept to victory in 1958 on a stridently white supremacist platform, commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body." (10) In his inaugural address Patterson declared: "I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state." (11)

Montgomery Bus Terminal Riot

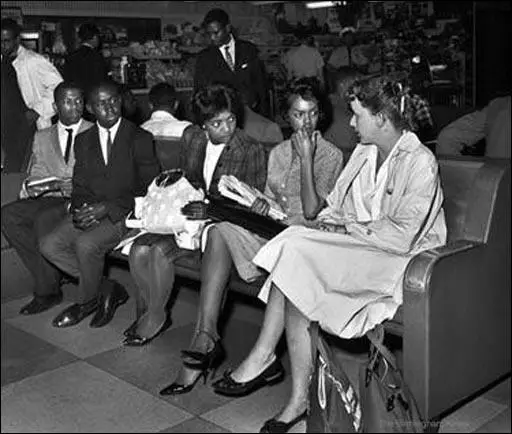

William Harbour took part in the third Freedom Ride that left Nashville, via Birmingham to Montgomery, on 17th May, 1961. Organised by Diane Nash and Fred Shuttlesworth, the bus included only two white passengers, James Zwerg and Salynn McCollum. Other members of CORE included John Lewis, William Barbee, Charles Butler, Catherine Burks, Lucretia R. Collins and Allen Cason. Lewis said: "As far as I was concerned, it was time to go... Time was wasting. This was a crisis, and we needed to act." Several handed Nash sealed letters "to be mailed if they were killed. Collins explained: "We thought some of us would be killed. We certainly thought that some, if not all of us, would be severely injured." (12)

and Salynn McCollum on 17th May, 1961.

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, ordered the arrest of all the Freedom Riders when they arrived in the city. As the only white female, Salynn McCollum was placed in a special facility, and Collins and Burks were put in a cell with several other black women. All the men ended up in a dark and crowded cell that Lewis likened to a dungeon. "It had no mattresses or beds, nothing to sit on at all, just a concrete floor." Harbour and his cellmates adopted a strategy of Gandhian non-cooperation. Lewis added "We went on singing both to keep our spirits up and - to be honest - because we knew that neither Bull Conner nor his guards could stand it." (13)

William Pritchard, one of Birmingham's leading attorneys, claimed: "I have no doubt that the Negro basically knows that the best friend he's ever had in the world is the Southern white man. He'd do the most for him - always has and will continue to do it, but when they, from Northern agitators, are spurred on to believe that they are the equal to the white man in every respect and should be just taken from savagery, and put on the same plane with the white man in every respect, that's not true. He shouldn't be... Even the dumbest farmer in the world knows that if he has white chickens and black chickens, that the black chickens do better if they're kept in one yard to themselves." (14)

Bull Connor announced that he was tired of listening to freedom songs and ordered the students to be taken back to Nashville. Salynn McCollum was released into her father's custody, was already on her wayback to New York. Walter McCollum told reporters: "I sent her to Nashville to get an education, not to get mixed up in this integration." Connor took them to the border town of Ardmore, Alabama, and advised them to take a train or bus back to Nashville. (15)

However, Harbour, John Lewis, James Zwerg, William Barbee, Catherine Burks, and others returned to Montgomery Bus Station. They were also joined by other Freedom Fighters including Susan Wilbur, Susan Herrmann, Bernard Lafayette, Paul Brooks, Allen Cason and Frederick Leonard. The Riders were prepared to spend the night at the terminal. Lewis commented: "We could see them through the glass doors and streetside windows, gestering at us and shouting. Every now and then a rock or a brick would crash through one of the windows near the ceiling. The police brought in dogs and we could see them outside, pulling at their leashes to keep the crowd back." (16)

and Bernard Lafayette at the Birmingham Greyhound bus station on May 19th, 1961.

A group of white men armed with lead pipes and baseball bats. Lewis later recalled: "Out of nowhere, from every direction, came people. White people. Men, women, and children. Dozens of them. Hundreds of them. Out of alleys, out of side seats, around the corners of office buildings, they emerged from everywhere, from all directions, all at once, as if they had been let out of a gate... They carried every makeshift weapon imaginable. Baseball bats, wooden boards, bricks, chains, tire irons, pipes, even garden tools - hoes and rakes. One group had woman in front, their faces twisted in anger, screaming." (17)

James Zwerg also received a terrible beating. Frederick Leonard commented that as Zwerg was a white man he was a particular target for their anger. "It was like those people in the mob were possessed. They couldn't believe that there was a white man who would help us... It's like they didn't see the rest of us for about thirty seconds. They didn't see us at all." (18) Klansmen kicked Zwerg in the back before smashing him in the head with his own suitcase. Lucretia R. Collins recalled: "Some men held him while white women clawed his face with their nails. And they held up their little children - children who couldn't have been more than a couple of years old - to claw his face. I had to turn my head because I just couldn't watch it." (19)

Susan Herrmann later recalled: "The mob kept closing in and starting yelling 'Get 'em! Get 'em!'. They picked up Jim Zwerg of Beloit College in Wisconsin, the only white boy in our group, and threw him on the ground. They kicked him unconscious. Still, we didn't fight back. But we didn't believe in running either. I saw some men hold boys, who were nearly unconscious, while white women hit them with purses. The white women were yelling 'Kill them!' and other nasty shouts. The police came and said they would put us in protective custody. They acted like we were crazy. They just couldn't understand why we would be freedom riders. But even though they did not believe in what we were doing, they did protect us and in that sense upheld the law." (20)

John Lewis had been felled by a blow from a wooden Coco-Cola crate and was laying unconscious on the ground. James Zwerg and William Barbee, were also on the ground. Barbee was being stomped and kicked by a taunting swarm of rioters who were shouting, ‘Kill him! Kill him!’ The lives of Zwerg, Lewis and Barbee, were all saved by Floyd Mann the Director of the Alabama Department of Public Safety. "I received some confidential information that when they arrived at the bus station in Montgomery that the police had planned to take a holiday, there'd be no one present." Mann arrived to find the mob trying to kill the Freedom Riders: "Those freedom riders, some of them were being beaten with baseball bats... I just put my pistol to the head of one or two of those folks who was using baseball bats and told them unless they stopped immediately, they was going to be hurt. And it did stop immediately." (21)

Attempts were made by journalists sent by newspapers from national newspapers to cover the Freedom Riders, to get the men to hospital. Police Commissioner L. B. Sullivan told inquiring reporters that all the ambulances for whites were out of service with breakdowns. Zwerg was put into the backseat of a white cab, which was promptly abandoned by the driver. An African-American taxi driver volunteered to take Lewis and Barbee to a hospital, but the segregation laws forced Zwerg to remain behind. Eventually, the police allowed Zwerg to be taken by a black ambulance to a Catholic hospital, which agreed to receive him. (22)

The women Freedom Riders ran for safety. The women approached an African-American taxicab driver and asked him to take them to the First Baptist Church. However, he was unwilling to violate Jim Crow restrictions by taking any white women. He agreed to take the five African-Americans, but the two white women, Susan Wilbur and Susan Herrmann, were left on the curb. They were now attacked by the white mob. (23)

John Seigenthaler, who had been sent by Attorney General Robert Kennedy to negotiate with Governor John Patterson of Alabama, tried to drive into the mob to save a young woman who was being attacked, According to Raymond Arsenault, the author of Freedom Riders (2006): "Suddenly, two rough-looking men dressed in overalls blocked his path to the car door, demanding to know who the hell he was. Seigenthaler replied that he was a federal agent and that they had better not challenge his authority. Before he could say any more, a third man struck him in the back of the head with a pipe. Unconscious, he fell to the pavement, where he was kicked in the ribs by other members of the mob." (24) The crowd "kicked his unconscious body halfway under the car." (25)

Robert Kennedy, called for a “cooling-off” period and a halt to the rides. The Freedom Riders refused to do this. Speaking from his hospital bed, James Zwerg, assured reporters that "these beatings cannot deter us from our purpose. We are not martyrs or publicity-seekers. We want only equality and justice, and we will get it. We will continue our journey one way or another. We are prepared to die." (26) William Barbee echoed Zwerg's pledge: "As soon as we're recovered from this, we'll start again... We'll take all the South has to throw and still come back for more." Unfortunately, Barbee was unable to do this as a result of the beating he received he was paralyzed for life and had an early death, (27)

William E. Harbour - Post 1961

On his return to Tennessee after the Freedom Rides, William Harbour and 14 other students were expelled from Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State University due to their involvement in the civil rights movement. Later, that year he was reinstated. In 1964 he worked as a Georgia school teacher. Harbour also worked with the "Community Relations Service and later as a civilian employee of the United States Army specializing in base closings." (28)

Primary Sources

(1) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006)

The chosen included two whites - Jim Zwerg and Salynn McCollum - and eight blacks: John Lewis, William Barbee, Paul Brooks, Charles Butler, Allen Cason, Bill Harbour, Catherine Burks, and Lucretia Collins.... Harbour, aged nineteen, was from Piedmont, Alabama, where his father worked in a yarn factory. Like fellow Alabamian John Lewis, Harbour was the first member of his family to go to college, and earlier in the year he and Lewis had struck up a friendship during a long bus to the jail-in rally in Rock Hill, South Carolina... While the ten Riders represented a range of the Nashville Movement. None had yet reached the age of twenty-three.

(2) Civil Rights Digital Library (2008)

Nineteen year old Tennessee State University student, William E. Harbour was first arrested for his involvement in a May 17 through May 21 Freedom Ride from Nashville, Tennessee to Montgomery, Alabama. Harbour was arrested a second time on May 28, 1961 after he rode a Greyhound bus from Nashville, Tennessee, via Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi as part of another Freedom Ride.

(3) Floyd Mann, Director of the Alabama Department of Public Safety, interviewed for the Eyes on the Prize documentary (18th February, 1986)

We picked up rumors several weeks prior to them arriving in Alabama. Also it was a certain something that the state police had not been confronted with in the past. We'd had local demonstrations by local people and, but this was the first time we'd had an interstate movement on the part of people. It was testing such things as lunch counters, water fountains, restrooms, so we knew that it would be a in all probability a police problem....

At this point in time most people in Alabama, that you'd hear speaking about this, thought the freedom riders were a group of people that - outsiders that were coming into the state that was coming to the state to cause problems. That's what the average person was saying around in Alabama at that time.

In the 1958 Governor's election, the choices was Governor John Patterson or Governor George Wallace... I believe at that point in time in Alabama, to those candidates it was very important that they receive support from people who felt very strongly on this issue. And so you will know more of what I mean, I'm talking uh about groups like the Ku Klux Klan, that type of people, because you have to remember at that point in time, in Alabama politics, that was before the voting act, how other people felt at that time was not of a great concern of people running for Governor...

We knew that the bus was going to be coming into Alabama from Atlanta, we did not have any communications or any information from those people about what route they'd be taking in Alabama, so we decided that for the benefit of the state police and also to try to protect this bus and the people on the bus, it would be important for us to have some type of information. So we sent one of the state investigators, a Mr. L. Cowden to Atlanta to board that bus. This was on Sunday, I remember, New Years Day of 1961...

We knew that it would be very important for the state police to know what route these people were going to take when they arrived in Alabama. So we thought it would be a good idea to send a state investigator to Atlanta to board this bus. And Mothers Day 1961 was when they arrived in Alabama; Anniston, Alabama. While this bus was in Anniston, uh, the Ku Klux Klan and other members surrounded that bus and would not let the people off the bus. While it was in the bus station they also cut the tires on the bus. They knew that those tires would go down, so when the bus left Anniston toward Birmingham, the Klan followed the bus out on the highway....

Several miles out of Anniston, the tire went down on the bus. The bus stopped. The Klan had followed the bus to this point. At that point they set the bus on fire, the Klansmen did. Those people on the bus could not get off the bus, and if we had not had the state investigator on the bus, I think everyone on the bus would have burned to death. But the investigator unlocked the door and pulled his gun and showed his badge and made the people back up and got the people off the bus. From that point they scattered around where the bus was burning and the more troopers arrived and then another bus arrived and they took that group on into Birmingham, where another outbreak occurred...

Police Commissioner Bull Connor was in charge of the police department in Birmingham at that time... To my best recollection when the bus arrived in Birmingham, I was informed that there was either no policemen or too few policemen there to handle the situation. Many people were hurt, injured, some seriously and what happened after that at that point in time to the people on the bus, I do not know, but I think they were all at some point carried to a central location....

After what happened in Anniston, Alabama and Birmingham, as director of public safety, I certainly knew that we had a tremendous problem on our hands. So did the governor, so did Attorney General Kennedy apparently, because at that point in time, he began to send people into Alabama, like Mr. John Siegenthaler, also Mr. Whizzel White, who's now a member of the Supreme Court, and others. So we began to try to develop some plan to get those people in and out of Alabama into Montgomery and on into Mississippi. So there were several meetings held, one in the Governors office, where I, Mr. John Siegenthaler attended, where he wanted the assurance from the governor that law and order would prevail in the state. Governor Patterson had certainly been elected as a law and order candidate, and I felt at that point in time, even though the political situation was such that I understood the situation that Governor Patterson was in politically. I also felt that Governor Patterson felt that I would make sure law and order did prevail in Alabama. So I assured Mr. Siegenthaler at that point in time that I felt that we could keep law and order in Alabama...

Governor Patterson at that time was in my opinion was in a terrible political situation because the very people who had so actively supported him strongly and openly were some of the people that was really very critical of these people coming into Alabama, the freedom riders, so I felt like that in all probability, Governor Patterson was in a situation whereby, that he had rather not make a commitment to the Government, in view of the situation he was in in Alabama...

I think both President Kennedy and the Attorney General Robert Kennedy felt that Governor Patterson as Governor of Alabama, should have no hesitancy at that time in making that commitment but I really don't think either one of them understood the position that the governor was in in Alabama politically, with his own constituency...

The state police and Mr. Siegenthaler, along with other governmental officials, maybe some marshals, assistants, we determined that the best way and the safest way to get those people into Montgomery and on into Mississippi, was to make certain that uh, they were protected. So when they left Birmingham we had 16 highway patrol cars in front of that bus, and 16 patrol cars behind the bus, with troopers, also we had small aircraft running reconnaissance, watching for bridges, where someone might try to sabotage that bus. During that period of time, I received some confidential information that when they arrived at the bus station in Montgomery that the police had planned to take a holiday, there'd be no one present. So we made sure that we didn't want to get in that situation so we ordered a hundred state troopers into Montgomery immediately. And we quartered those troopers at the Alabama police academy because we didn't want to bring them into the bus station because at that point in time in Alabama the state police never entered a city unless they were invited. Either it became obvious that law and order had totally broken down… So at the time the bus arrived at the Montgomery bus station, only the assistant director Mr. W.R. Jones and myself was there when the bus arrived. As soon as the people began to get off the bus I noticed these strange people all around the bus which I knew immediately they were Klansmen. No sooner than they had gotten off the bus a riot evolved. At that point in time it certainly became obvious to me that law and order had broken down and there's no police around the bus station. So we immediately sent for those hundred state troopers that we had quartered at the police academy. And prior to them arriving there, several people hurt and we had to command cars to take some to the hospital...

Those freedom riders, some of them were being beaten with baseball bats, some of the newspeoples' cameras were being crushed. Therefore we did have to resort to pulling out weapons, to stop that and also to get some of those people to the hospital. I just put my pistol to the head of one or two of those folks who was using baseball bats and told them unless they stopped immediately, they was going to be hurt. And it did stop immediately....

After one of the freedom riders were knocked unconscious we got him to a car, sent him to the hospital. Then it was called to my attention that another person had been knocked unconscious and had been taken to the hospital and I retrieved his credentials and they, I think they had fallen out of his pocket in front of the bus station, and looking at those credentials I saw it was Mr. John Siegenthaler. After the troopers got things totally under control at the bus station, I then went to the hospital to verify if it was Mr. Siegenthaler and it was Mr. Siegenthaler and he'd been knocked unconscious.