Diane Nash

Diane Nash was born in Chicago on 15th May, 1938. She was raised by her father Leon Nash and her mother Dorothy Bolton Nash, in a middle-class Catholic area. Leon Nash left the family when she was young. After the divorce Dorothy married John Baker, a waiter on the railroad dining cars owned by the Pullman Company, who was active in the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, one of the most powerful black unions in the country. (1)

Diane's grandmother Carrie Bolton had a major influence on her. At the age of nine, she became a maid in a white Memphis family’s home. She also looked after Diane because both her parents were out at work. Nash said Bolton shaped the family’s views on race. Diane's son, Douglass Bevel, later recalled: "My great-grandmother was a woman of great patience and generosity. She loved my mother and told her no one was better than her and made her understand she was a valuable person. There’s no substitute for unconditional love, and my mother is just really a strong testament to what people who have it are capable of.” (2)

David Halberstam has pointed out in his book, The Children (1998), that Nash had no real interest in politics and civil rights as a teenager and even took part in a regional beauty pageant leading to the competition for Miss Illinois: "She (Diane Nash) had grown up on the south side of Chicago in a rather privileged environment. She had even been, although it was not something she liked to boast about at the time, a teenage beauty queen, competing in the local Miss America contest in 1956 as a high school student." (3)

Diane Nash: Civil Rights Activist

Diane Nash attended Howard University. It had been established by a charter of the U.S. Congress on 2nd March, 1867. Instigated by the Radical Republicans it was named after General Oliver Howard, an American Civil War hero and a leading figure in the Freeman's Bureau. The following year she transferred to Fisk University, where she majored in English. It was in Nashville, she was first exposed to the full force of Jim Crow laws and customs and later recounted her experience at the Tennessee State Fair when she had to use the "Colored Women" restroom. (4)

In the late 1950s Nash joined Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Members were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. CORE became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America. (5)

Nash started taking part in non-violence training classes run by James Lawson at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle. Rosa Parks attended a 1955 workshop at Highlander four months before refusing to give up her bus seat, an act that ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Other people on the course included John Lewis, Marion Barry and James Bevel. The students role-played demonstrators and attackers to prepare themselves for the hatred they would encounter. It was not long before she was elected chairperson of CORE in Nashville. (6)

CORE decided to campaign to bring an end to segregated seating in restaurants. In Greensboro, North Carolina, a small group of black students decided to take action themselves. On 1st February, 1960, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, Joseph McNeil and Ezell Blair, started a student sit-in at the restaurant of their local Woolworth's store which had a policy of not serving black people. In the days that followed they were joined by other black students until they occupied all the seats in the restaurant. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of Martin Luther King they did not hit back. McCain later recalled: "On the day that I sat at that counter I had the most tremendous feeling of elation and celebration. I felt that in this life nothing else mattered. I felt like one of those wise men who sits cross-legged and cross-armed and has reached a natural high." (7)

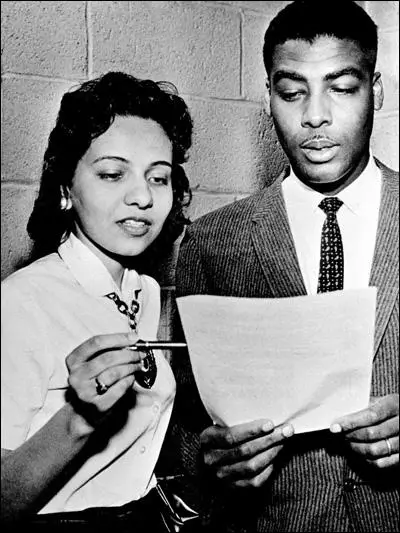

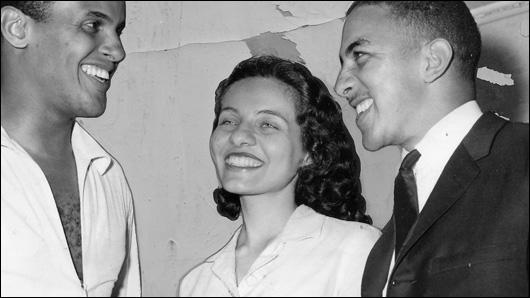

Diane Nash and CORE began a campaign against segregated seating in Nashville in February 1960. They achieved their first success when Nash, Matthew Walker Jr., Peggy Alexander and Stanley Hemphill became the first blacks to eat lunch at the Post House Restaurant in the Nashville Greyhound Bus Terminal. It was the first Southern city where blacks and whites could sit together for lunch. As one civil rights activist pointed out: “It was the first time anyone in a leadership position who could make a difference, made a difference." (8) Students continued the sit-ins at segregated lunch counters for months, accepting arrest in line with nonviolent principles. During this period Nash emerged as one of the leaders of the sit-in movement. (9)

at the Post House Restaurant in Nashville. From left to right: Matthew Walker Jr., Peggy

Alexander, Diane Nash and Stanley Hemphill. (16th May, 1960)

Sit-ins continued through the following year, and on 6th February, 1961. Diane Nash and three other SNCC leaders (Charles Jones, Ruby Doris Smith and Charles Sherrold) went to jail after supporting the “Rock Hill Nine” or “Friendship Nine,” nine students incarcerated after a lunch counter sit-in in Rock Hill, South Carolina. The students would not pay bail after their arrests because they believed paying fines supported the immoral practice of segregation. The unofficial motto of student activists was “jail, not bail.” Eventually over a 100 served a month in prison. (10)

Freedom Riders

In February, 1961, CORE organized a conference in Kentucky where the organization laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge the racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (11) John Lewis, a student at Nashville American Baptist Theological Seminary, commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." (12)

Diane Nash was one of those who volunteered to join the Freedom Riders. James Farmer and his staff tried to come up with a reasonably balanced mixture of black and white, young and old, religious and secular, Northern and Southern. The only deliberate imbalance was a lack of women. The CORE leadership was reluctant to expose women, especially black women, to potentially violent confrontations with white supremacists. "Their decision to limit the number of female Freedom Riders to two was undoubtedly rooted in patriarchal conservatism, but they also feared that a balanced contingent of men and women might be interpreted as a provocative pattern of sexual pairing. The situation was dangerous enough, they reasoned, without taunting the segregationists with visions of interracial sex." (13)

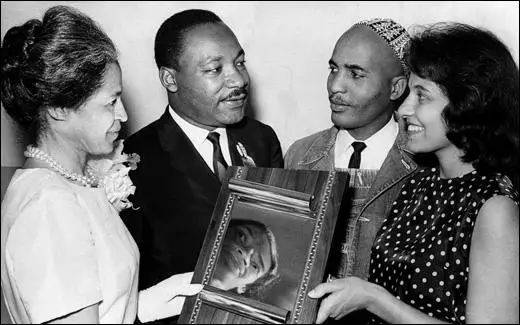

However, she was rejected and asked to organise the campaign from CORE headquarters. When the police in the Deep South began arresting and imprisoning the riders, Nash traveled to Montgomery to have a crisis meeting with John Lewis, Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy. If the rides were to continue, they needed to ask for more volunteers to take the rides. Lewis later explained: "We had a press conference the next afternoon, Reverend Abernathy, Dr. King, Diane Nash, and myself. From the backyard of Reverend Abernathy's home, we announced to the nation that the Freedom Ride would continue, that we would not stop." (14)

Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent John Seigenthaler to negotiate with Governor John Patterson of Alabama. Patterson told Seigenthaler that he was more popular than President John F. Kennedy and vowed to hold the line "against Martin Luther King and these rabble-rousers". He added "I want you to know that if schools in Alabama are integrated, blood's gonna flow in the streets, and you take the message back to the President and you tell the Attorney General that." (15)

Harris Wofford, the president's Special Assistant for Civil Rights, later pointed out: "Seigenthaler arrived in time to escort the first group of wounded and shaken riders from the bus terminal to the airport, and flew with them to safety in New Orleans. He had to hurry back, for James Farmer was arriving at the Alabama border with a new group, joined by a contingent from Nashville, including student sit-in leaders James Lawson, John Lewis, and Diane Nash; Lawson, who had studied with Gandhi during three years as a student missionary in India, said they would go by bus all the way to New Orleans, by way of Alabama and Mississippi, or die trying." (16) Seigenthaler called Nash and tried to persuade her to call off the ride. “I’m saying, You’re going to get somebody killed." She replied, "You don’t understand, we signed our wills last night." (17)

Fred Shuttlesworth and other Civil Rights campaigners, joined Diane Nash, John Lewis, Wyatt Tee Walker who were fit enough to carry on with the ride into the Deep South. Governor Patterson branded the Freedom Riders as "outlaws" and they were forced to take refuge in Montgomery's First Baptist Church. King telephoned the Attorney General to complain about the situation and was not very pleased when he replied: "Now, Reverend, don't tell me that. You know just as well as I do that if it hadn't been for the United States marshals, you'd be dead as Kelsey's nuts right now!" (18)

However, with his attempts to please racist Democratic politicians in the Deep South, he came under attack from the liberal press in the North. For example, The New York Times published an editorial that said: "The issue in Montgomery is the right of American citizens, white and Negro alike, to travel in safety in interstate commerce, without being tested by the so-called Freedom Riders, a racially mixed group consisting primarily of students, who are waging their campaign for civil rights in the South in a Gandhian sprit of idealism and of non-violent resistance to an evil tradition." (19)

Mass Arrests in Mississippi

The Freedom Riders intended to move their protest to Mississippi. President John F. Kennedy made one last attempt to stop this happening and telephoned Martin Luther King to call-off the action and persuade them to post bonds so that they could leave prison. King replied: "It's a matter of conscience and morality. They must use their lives and bodies to right a wrong. Our conscience tells us that the law is wrong and we must resist, but we have a moral obligation to accept the penalty." Kennedy insisted: "That is not going to have the slightest effect on what the government is going to do in this field or any other. The fact that they stay in jail is not going to have the slightest effect on me." (20)

The media was to play an important role in changing the attitudes of the Kennedy administration. On the first bus that left Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi, on 24th May, 1961, the 12 Freedom Riders led by James Lawson, were joined by members of the National Guard and several journalists. The second bus the Freedom Riders were led by John Lewis and the third bus by the Baptist minister, John Lee Copeland. The following day the fourth bus left Montgomery. Those on board included three Baptist ministers, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Wyatt Tee Walker and William Sloane Coffin, chaplain of Yale University. (21)

When the buses arrived at the Jackson Terminal, the Freedom Riders, black and white, went into the white waiting room. Several also used the white rest-room. They were immediately arrested. They refused an offer by NAACP attorneys to post a thousand-dollar bond for each defendant. When the Baptist minister, Ralph Abernathy was asked about Robert Kennedy's complaint that the Freedom Riders were embarrassing the nation in front of the world, he responded: "Well doesn't the Attorney General know we've been embarrassed all our lives?" (22)

During the summer of 1961 freedom riders also campaigned against other forms of racial discrimination. They sat together, in segregated restaurants, lunch counters and hotels. This was especially effective when it concerned large companies who, fearing boycotts in the North, began to desegregate their businesses. Norman Thomas described these young people as "secular saints" (23) I. F. Stone argued: "They and a few white sympathizers as youthful and devoted as themselves have begun a social revolution in the South with their sit-ins and their Freedom Rides. Never has a tinier minority done more for the liberation of a whole people than these few youngsters of C.O.R.E. (Congress for Racial Equality) and S.N.C.C. (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee)." (24)

Martin Luther King claimed that he "hundred of thousands" of students willing to travel to the Deep South to join the protests. The administration decided it had to take action. Robert Kennedy now petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to draft regulations to end racial segregation in bus terminals. The ICC was reluctant but in September 1961 it issued the necessary orders and it went into effect on 1st November. However, James Lawson, one of the Freedom Riders, argued: "We must recognize that we are merely in the prelude to revolution, the beginning, not the end, not even the middle. I do not wish to minimize the gains we have made thus far. But it would be well to recognize that we have been receiving concessions, not real changes. The sit-ins won concessions, not structural changes; the Freedom Rides won great concessions, but not real change." (25)

Stokely Carmichael commented that "Everybody wanted to marry Diane. She was warm, she was gentle, she was so brave, she was so intelligent, she was so pretty. Everybody wanted Diane Nash. Everybody." The feminist historian, Lynne Olson, has pointed out: "As products of the post-war teenage culture, women of her generation had been encouraged to believe they were special, to do well in school, to develop their talents and abilities. Then they were expected to exchange that early independence and assertiveness for a lifetime of self-denial and dependence on men." Olson quotes Margaret Mead as saying: "Women could define herself as a woman, and therefore less on achieving individual and therefore less of a woman." (26)

In 1961 Diane Nash married James Bevel, a fellow Freedom Rider. According to Nadra Kareem Nittle: "Marriage didn’t slow down her activism. In fact, while she was pregnant in 1962, Nash had to contend with the possibility of serving out a two-year prison sentence for giving civil rights training to local youth. In the end, Nash served just 10 days in jail, sparing her from the possibility of giving birth to her first child, Sherrilynn, while incarcerated. But Nash was prepared to do so in hopes that her activism could make the world a better place for her child and other children. Nash and Bevel went on to have son Douglass." (27)

Most of Diane Nash's friends were surprised by the marriage and did not expect it to last very long. "Bevel was a womanizer, someone who like ministers in the past seemed to believe that part of pastoring to his flock was being intimate with women in the congregation. Marriage had not changed his habits, and it had been bitterly frustrating for Diane in their early years together." (28)

Selma Voting Rights Campaign

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham.

On Sunday, 15th September, 1963, a white man was seen getting out of a white and turquoise Chevrolet car and placing a box under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Soon afterwards, at 10.22 a.m., the bomb exploded killing Denise McNair (11), Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Robertson (14) and Cynthia Wesley (14). The four girls had been attending Sunday school classes at the church. Twenty-three other people were also hurt by the blast. The bombing was the fourth in less than a month, and fiftieth in two decades, in what had become known as "Bombingham." (29)

Diane Nash and her husband, James Bevel, in response to the bombing, became committed to raising a nonviolent army in Alabama. Its main objective was obtaining the vote for every black adult in the state. Alabama and other southern states had effectively excluded blacks from the political system since disenfranchising them at the turn of the century. In 1962, Deputy Attorney General Burke Marshall reported that “racial denials of the right to vote” existed in eight states, with only fourteen percent of eligible black citizens registered to vote in Alabama. In Mississippi, 42% of the population were black but only 2% were registered to vote. (30)

This eventually became known as the Selma Voting Rights Campaign. Nash told Martin Luther King: "He (King) could notorious a battered people for nonviolent action and then give them nothing to do. After the church bombing, she and Bevel had realized that a crime so heinous pushed even nonviolent zealots like themselves to the edge of murder. They resolved to do one of two things; solve the crime and kill the bombers, or drive (Governor George Wallace and Police Chief Albert J. Lingo) from office by winning the right for Negroes to vote across Alabama." (31)

Diane Nash’s activism attracted the attention of President John F. Kennedy, who selected her to serve on a committee to develop a national civil rights platform, which later became the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The next year, Nash planned marches from Selma to Montgomery to support voting rights for African Americans in Alabama. When the peaceful protesters tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge to head to Montgomery, police severely beat them. Stunned by images of law enforcement agents brutalizing the marchers, Congress passed the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Nash’s efforts to secure voting rights for Black Alabamians resulted in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference awarding her the Rosa Parks Award. (32)

Diane Nash became concerned about United States foreign policy. She applied pressure on Martin Luther King Jr. to oppose the Vietnam War and they worked together on a desire to encourage peace negotiations. Nash traveled overseas with three other American women, stopping in Moscow and Peking before landing in Hanoi for an interview with North Vietnam’s president, Ho Chi Minh. In one speech she claimed U.S. bombings were “deliberately aimed at helpless villages.” This resulted in her passport being revoked. (33)

Nash also encouraged King to become more involved in the campaign against economic inequality. The FBI became concerned about King's political development, especially when he became a strong opponent of the Vietnam War. The FBI bugged his telephones and hotel rooms and bribed King's staff into giving them information about him. Details about his private life and left-wing political friends were leaked to the press. The FBI also sent King an anonymous blackmail letter in an attempt to force him to retire from political life. Many of King's close friends believe that these events are connected with his assassination. King was in Memphis speaking in support of low paid striking sanitation workers when he was shot allegedly by James Earl Ray on 4th April, 1968. (34)

Recent Political Campaigns

Diane Nash supported Barack Obama in his campaign to become president, but was disappointed by his foreign policy and his decision to continue the United States involvement in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nash still believes that the true changes in American society will come from its citizens, not government officials."I am glad we have a black president. I think there are many positive things involved with that.... I don’t think what needs to be done in this country is going to be done by elected officials. American citizens have to take the country into our own hands, the future of this country, and do what’s necessary.” (35)

Although she attended the Selma 50th anniversary celebrations in March 2015, Nash was absent from the restaging of the 1965 Selma march. Nash told a journalist: "I refused to march because George Bush marched. I think the Selma movement was about non-violence and peace and democracy. And George Bush stands for just the opposite. For violence and war and stolen elections.... I think that George Bush’s presence is really an insult to me and people who do not believe in non-violence.” (36)

In a speech made at Yale University in January 2017 Diane Nash pointed out except for Rosa Parks, very few women have not been given enough enough credit for their role in the Civil Rights Movement. This included Ella Josephine Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Peggy Alexander and Mary Hamilton. “Besides Rosa Parks, few people can name women in the Civil Rights Movement and what their contributions were. Ella Baker contributed as much to the Civil Rights movement as Martin Luther King." Nash also acknowledged the "accomplishments of other often-forgotten women, including voting rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, active sit-in participant Peggy Alexander and field organizer Mary Hamilton." Nash complained that: “Media and history books often frame the civil rights movement as King’s movement. That’s not true. It was a people’s movement.” (37)

Primary Sources

(1) David Halberstam, The Children (1998)

During those extraordinary weeks and months, Diane Nash was quite surprised by the change which had taken place in herself. She had never thought of herself as a political person and, even more, had never thought of herself as a leader. She had grown up on the south side of Chicago in a rather privileged environment. She had even been, although it was not something she liked to boast about at the time, a teenage beauty queen, competing in the local Miss America contest in 1956 as a high school student.

(2) Heidi Nieland Hall, The Tennessean (2nd March, 2017)

Diane Nash... spent months coordinating Freedom Rides of buses full of black and white protesters across the South. She’d resisted anyone, including the Kennedy administration, who told her to stop them.

By the spring of 1962, at the age of 23, she had long achieved indispensable status in the male-dominated civil rights movement. Her quiet persistence, in fact, had played a critical role in pricking the conscience of Nashville as it became the first Southern city to desegregate lunch counters.

Now, six months pregnant, she faced a 21/2-year sentence for contributing to the delinquency of the underage students she’d encouraged to ride on the buses. Or she could fight it.

She re-emerged in the public eye with her convictions intact. “I believe that if I go to jail now,” she wrote in an open letter, “it may help hasten that day when my child and all children will be free - not only on the day of their birth but for all their lives.”

Ultimately, the judge sentenced her to 10 days in a Jackson, Miss., jail. She spent her time there washing her only set of clothing in the sink during the day and listening to cockroaches skitter overhead at night.

(3) Nadra Kareem Nittle, Diane Nash, Civil Rights Leader and Activist (12th November, 2018)

As a Fisk student, Nash embraced the philosophy of nonviolence, associated with Mahatma Gandhi and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. She took classes on the subject run by James Lawson, who’d gone to India to study Gandhi’s methods. Her nonviolence training helped her lead Nashville’s lunch counter sit-ins over a three-month period in 1960. The students involved went to “whites only” lunch counters and waited to be served. Rather than walking away when they were denied service, these activists would ask to speak with managers and were often arrested while doing so.

Four students, including Diane Nash, had a sit-in victory when the Post House Restaurant served them on March 17, 1960. The sit-ins took place in nearly 70 US cities, and roughly 200 students who took part in the protests traveled to Raleigh, N.C., for an organizing meeting in April 1960. Rather than function as an offshoot of Martin Luther King’s group, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the young activists formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. As a SNCC co-founder, Nash left school to oversee the organization’s campaigns.

Sit-ins continued through the following year, and on February 6, 1961, Nash and three other SNCC leaders went to jail after supporting the “Rock Hill Nine” or “Friendship Nine,” nine students incarcerated after a lunch counter sit-in in Rock Hill, South Carolina. The students would not pay bail after their arrests because they believed paying fines supported the immoral practice of segregation. The unofficial motto of student activists was “jail, not bail.”

(4) Liana van Nostrand, Yale News (26th January, 2017)

Over 500 Yale affiliates and New Haven residents gathered in Battell Chapel on Wednesday night to hear Diane Nash, who served as one of the key strategists for the 1960 Nashville sit-ins, deliver this year’s Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Lecture.

Nash spoke about her experiences as a student and woman in the civil rights movement and on the importance of nonviolence. The two-hour event concluded with a representative from the Mayor’s Office presenting Nash with a proclamation that celebrates the legacy of King and recognizes her contributions.

Nash opened her talk with the story of how she met King. Her serious speech was peppered with light remarks including a mention of a double date with King and his wife Coretta Scott King.

“Following segregation rules made it seem like I was agreeing I was inferior,” Nash said as she recalled her experiences after moving from the south side of Chicago to Nashville, Tennessee to attend Fisk University.

Eager to combat segregation, she attended workshops in nonviolence, helped lead the effort to integrate lunch counters in Tennessee, and successfully worked to desegregate interstate buses as a member of the Freedom Riders, a group of civil rights activists who fought against segregation on buses in the South.

These efforts were not without struggle, Nash said. She spoke about the first Freedom Ride, which had to be disbanded because the bus was firebombed and the people severely beaten. She also recalled thinking she would have her first child in jail, as well as other struggles women of the Civil Rights Movement faced.

“Besides Rosa Parks, few people can name women in the Civil Rights Movement and what their contributions were,” Nash said. “Ella Baker contributed as much to the Civil Rights movement as Martin Luther King [Jr.].”

She also acknowledged the accomplishments of other often-forgotten women, including voting rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, active sit-in participant Peggy Alexander and field organizer Mary Hamilton.

Nash also outlined the tenets of nonviolence: the major principles of the strategy and the six phases of enacting it. Her impassioned defense of the approach implored the public to struggle for freedom instead of waiting for elected officials to provide it.

In conclusion, she addressed how common narratives of King’s work often ignore critiques from within the movement, adding that many activists thought he worked too slowly.

“Media and history books often frame the civil rights movement as King’s movement,” Nash said. “That’s not true. It was a people’s movement.”