On this day on 18th January

On this day in 1764, Samuel Whitbread, the only son and third child of Samuel Whitbread, and Harriet Hayton, was born in Cardington near Bedford. His mother died three months after he was born. His father was a highly successful businessman and was the owner of the Whitbread Brewery. His father married Mary Cornwallis, younger daughter of Earl Cornwallis, in 1769. Tragically, the following year, Mary died in childbirth.

According to his biographer, D. R. Fisher: "The younger Whitbread's upbringing was largely joyless, and great care was lavished on his education by his well-meaning but overbearing father." When Samuel was sent to Eton College he was accompanied by his own private tutor. At Eton he met his lifelong friends, Charles Grey and William Henry Lambton. Samuel continued his education at Christ Church and St. John's College.

After university Samuel Whitbread sent his son on a tour of Europe, under the guidance of the historian, William Coxe. This included visits to Denmark, Sweden, Russia, Poland, Prussia, France and Italy. When Samuel returned in May 1786, he joined his father running the extremely successful family brewing business. The Whitbread Brewery was making an average yearly profit of £18,000. Whitbread had purchased a Boulton & Watt steam engine to grind malt and to pump water up to the boilers. This enabled the brewery to increase production to 143,000 barrels a year. This established Whitbread as the largest brewer in Britain. Peter Mathias argues: "Public renown came on 27 May 1787 with a royal visit to Chiswell Street - by the king and queen, three princesses, and an assembly of aristocrats in train - with James Watt on hand to explain the mysteries of his engine."

In 1789 Samuel Whitbread married Elizabeth Grey, the sister of Charles Grey. The two men were deeply interested in politics. Grey was already MP for Northumberland and in 1790 Whitbread was elected MP for Bedford. In the House of Commons, Whitbread and Grey became followers of Charles Fox, the leader of the Radical Whigs. Whitbread soon emerged in Parliament as a powerful critic of the Tory Prime Minister, William Pitt. A passionate supporter of reform, Whitbread argued for an extension of religious and civil rights, an end to the slave-trade, and the establishment of a national education system.

In April 1792, Whitbread joined with a group of pro-reform Whigs to form the Friends of the People. Three peers (Lord Porchester, Lord Lauderdale and Lord Buchan) and twenty-eight Whig MPs joined the group. Other leading members included Charles Grey, Richard Sheridan, John Cartwright, John Russell, George Tierney, and Thomas Erskine. The main objective of the the society was to obtain "a more equal representation of the people in Parliament" and "to secure to the people a more frequent exercise of their right of electing their representatives". Charles Fox was opposed to the formation of this group as he feared it would lead to a split the Whig Party.

On 30th April 1792, Charles Grey introduced a petition in favour of constitutional reform. He argued that the reform of the parliamentary system would remove public complaints and "restore the tranquillity of the nation". He also stressed that the Friends of the People would not become involved in any activities that would "promote public disturbances". Although Charles Fox had refused to join the Friends of the People, in the debate that followed, he supported Grey's proposals. When the vote was taken, Grey's proposals were defeated by 256 to 91 votes.

In 1793 Samuel Whitbread toured the country making speeches on the need for parliamentary reform. He encouraged people to sign petitions at his meetings and when he returned to London they were presented to Parliament. Whitbread also campaigned on behalf of agricultural labourers. In the economic depression of 1795, Whitbread advocated the payment of higher wages. When Whitbread introduced his minimum wage bill to the House of Commons in December 1795 it was opposed by William Pitt and his Tory government and was easily defeated.

Whitbread was a strong supporter of a negotiated peace with France and supported Fox's calls to send a government minister to Paris. Whitbread argued for Catholic Emancipation and opposed the act for the suppression of rebellion in Ireland. His friend, Samuel Romilly, said that Whitbread was "the promoter of every liberal scheme for improving the condition of mankind, the zealous advocate of the oppressed, and the undaunted opposer of every species of corruption and ill-administration." Whitbread's attempts in 1796 to empower magistrates to fix a minimum wage was unsuccessful.

Whitbread supported Grey's protest against the renewal of war on 24 May 1803, and was active in the combined attack on Henry Addington in 1804. The following year he charged Viscount Melville with alleged financial malpractice during his tenure as First Lord at the Admiralty. It has been argued by D. R. Fisher: "Whitbread gained much credit for the tenacity with which he conducted it. Its initial success helped to stimulate a revival of radicalism in the country, as well as fatally weakening Pitt's feeble second ministry. Whitbread regarded it as a considerable personal triumph, though Melville's acquittal in June 1806 and the ridicule excited by lapses of taste and judgement in his own concluding speech of 16 May detracted from it."

In 1807 Samuel Whitbread proposed a new Poor Law. His scheme not only involved an increase in the financial help given to the poor, but the establishment of a free educational system. Whitbread proposed that every child between the ages of seven and fourteen who was unable to pay, should receive two years' free education. The measure was seen as too radical and was easily defeated in the House of Commons.

Whitbread refused to be disillusioned by his constant defeats and during the next few years he made more speeches in the House of Commons than any other member. Sometimes his attacks on George III and his ministers were considered to be too harsh, even by his closest political friends.

Unable to persuade Parliament to accept his ideas, Whitbread used his considerable fortune (his father, Samuel Whitbread had died in 1796) to support good causes. His net income from land (about £12,600 a year) almost always exceeded brewery profits (about £8,000). Whitbread gave generous financial help to establish schools for the poor. An advocate of the monitorial system developed by Andrew Bell and Joseph Lancaster, he helped fund the Royal Lancasterian Society that had the objective of establishing schools that were not controlled by the Church of England.

When the Whigs gained power in 1806, Whitbread expected the Prime Minister, Lord Grenville, to offer him a place in his government. He was deeply disappointed when this did not happen. Some claimed it was because Whitbread was too radical. Others suggested it was due to snobbery and the aristocrats in the party disapproved of a tradesman entering the cabinet. Grenville did promise the post of secretary of war as soon as the incumbent, Richard Fitzpatrick, could be moved to another position. However, nothing had been done about this when the ministry fell in March 1807.

After this rejection, Whitbread consoled himself with his involvement in the Drury Lane Theatre. In 1809 the theatre was destroyed by fire. Already over £500,000 in debt, the theatre was in danger of going out of business. Whitbread became chairman of the committee set up to rebuild the theatre. With the help of his political friends, Whitbread managed to raise the necessary funds and the Drury Lane Theatre was reopened on 10th October, 1812.

In May 1812 Whitbread split with the Whigs when Lord Grenville renounced all future political co-operation with him. He did work fairly closely with Henry Brougham but as his biographer, D. R. Fisher, points out: "For the rest of his life Whitbread was an outcast from the main body of opposition. He kept up his obsessive demands for peace negotiations and sought, to a limited extent, to promote economic and parliamentary reform. His involvement in 1813 in the campaign on behalf of the princess of Wales, in which he acted as Henry Brougham's lieutenant, was a waste of his talents.... He renewed his efforts in Caroline's cause in 1814, but only succeeded in playing into the hands of ministers and exasperating Brougham."

Robert Heron, the MP for Great Grimsby, commented: "Though his harsh and overbearing manners had, for a long time, been obnoxious to many of all ranks, and particularly to the poor, even whilst they received benefits from him; yet, the experience of his honesty, his enlightened benevolence, and his indefatigable exertions in almost every department of town and country business had, at length, procured for him universal respect, and, out of Parliament, almost universal acquiescence in his measures; and, probably, few men have been so extensively useful to the country… In Parliament, his bad taste and, what is perhaps the same thing, want of judgment, above all, his impractical disposition, diminished greatly the advantages which might otherwise have been derived from his great ability as an orator, his experience, and his incorruptible firmness. Samuel Romilly was more complimentary, "the only faults he had proceeded from an excess of his virtues."

In 1815 Samuel Whitbread began to suffer from depression. Over the years he had been upset by the way he was portrayed by the political cartoonists such as, James Gillray and George Cruikshank. He also began to worry about the brewery business and the way he was treated in the House of Commons. After one debate in June he told his wife: "They are hissing me. I am become an object of universal abhorrence." On the morning of 6th June 1815, Samuel Whitbread committed suicide by cutting his throat with a razor at his London house at 35 Dover Street, Mayfair.

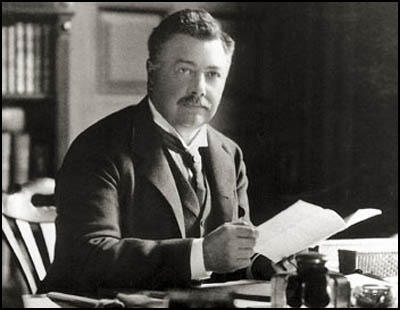

On this day in 1850 progressive politician Seth Low was born in Brooklyn, New York. After graduating from Columbia College in 1870, Low joined his father's silk importing business.

A successful businessman, Low became involved in local politics and was twice elected to the post of mayor of Brooklyn (1881-85) where he developed a reputation for honesty and efficiency. He also served as president of Columbia College (1890-1901), where he paid for new buildings on the campus and supported higher education for women.

Low took a keen interest in politics. In 1891 he wrote: "It is estimated that the population of New York City contains 80 per cent of people who either are foreign-born or who are the children of foreign-born parents. Consequently, in a city like New York, the problem of learning the art of government is handed over to a population that begins in point of experience very low down. It many of the cities of the United States, indeed in almost all of them, the population not only is thus largely untrained in the art of self-government but it is not even homogeneous; so that an American city is confronted, not only with the necessity of instructing large and rapidly growing bodies of people in the art of government but it is compelled at the same time to assimilate strangely different component parts into an American community."

Seth Low, with the support of Charles Parkhurst, the president of the Society for the Prevention of Crime, led the campaign against corruption in New York City. After a long struggle, Low became the new mayor of the city in 1901 when he defeated Richard Croker and the Tammany political machine. Lincoln Steffens reported: "The mayor of New York, Seth Low, was a business man and the son of a business man, rich, educated, honest, and trained to his political job. Seth Low and his party in power and his backers were not radicals in any sense. Mr. Low himself was hardly a liberal; he was what would be called in England a conservative. He accepted the system; he took over the government as generations of corrupters had made it, and he was trying, without any fundamental change, and made it an efficient, orderly business-like organization for the protection and the furtherance of all business, private and public."

As well as serving as mayor of New York City (1901-03), Low was chairman of the Tuskegee Institute (1907-1916) in Alabama. Seth Low died on 17th September, 1916.

On this day in 1869 militant suffragette Constance Lytton, the daughter of Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton and Edith Villiers, was born in Vienna on 18th January 1869. Lytton was the Viceroy of India and Constance spent the first eleven years of her life in India. Educated by a series of governesses she had a very lonely childhood.

In 1892 Constance fell in love with a man with lower social status than the Lytton family. Lord Lytton had died the previous year, but her mother refused to grant permission for her to marry this man. For several years she hoped her mother would change her mind, but this did not happen and Constance Lytton refused to contemplate marrying anyone else.

Constance Lytton's sister Betty Bulwer-Lytton, married Gerald Balfour, a keen supporter of the women's suffrage movement. So also were two of his sisters, Frances Balfour and Emily Lutyens. Constance found their ideas on women's political rights interesting but her preoccupation with her unhappy love affair and poor health stopped her joining the suffrage movement.

In 1906 Constance Lytton visited the Espérance Club, an organisation that had been established by Mary Neal and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. The club was influenced by the ideas of William Morris, Edward Carpenter, and Walt Whitman. The women were also involved in helping a group of young women establish a co-operative dressmaking business, Maison Espérance, in Wigmore Street.

Mary Neal and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were also active members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). At first she disagreed with their militant tactics. In a letter written on 8th September 1906 she told Adela Smith: "I met some suffragettes down at the club in Littlehampton… I had a long talk with Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. She mostly talked Woman Suffrage, about which, though I sympathize with the cause, she left me unconverted as to my criticisms of some of their methods."

However, she was willing to help the women who had been imprisoned as a result of their actions: "They (the suffragettes) have come into personal first-hand contact with prison abuses. My hobby of prison reform has thereby taken on new vigour… I intend to interview the female inspector of Holloway prison, and will take part in the Suffragette breakfast with the next batch of released Suffrage prisoners on September 16." Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence also asked her to seek a meeting with Herbert Gladstone: " Could I see to it that Herbert Gladstone was asked to treat the Suffragettes as political offenders, which they are, and not as common criminals, which they are not?"

In November 1908 Constance Lytton told her aunt, Theresa Earle: "I go deeper and deeper in my enthusiasm to the women, and even for their tactics as I understand it more and more - not only what they do, but what has been done to them to drive them to these tactics." She was especially impressed with Annie Kenney, who was one of the WSPU's full-time organisers. Lytton later wrote in Prison and Prisoners (1914): "Women had tried repeatedly, and always in vain, every peaceable means open to them of influencing successive governments. Processions and petitions were absolutely useless. In January 1909 I decided to become a member of the Women's Social and Political Union."

Constance Lytton's decision to join the WSPU horrified her family. Her sister, Emily Lutyens, who was a supporter of the non-militant, National Union of Suffrage Societies, wrote to her aunt, Theresa Earle: "I must write you a line of deepest sympathy. I know how you must be suffering about Constance. We cannot disguise from ourselves that our old Constance has gone forever. I feel, whatever it may be in the future, for the moment she has passed out of the lives of her family. She has become an impersonal being, and no one will feel this so much as you."

On 24th February 1909, Constance took part in a demonstration at the House of Commons. Constance was arrested and imprisoned but when the authorities found out that she was the daughter of Lord Lytton, the former Viceroy of India, they ordered her release. As well as her social position, the British government were also aware of Constance Lytton's health problems, and they feared that if she went on hunger strike she would die and then the WSPU would have a famous martyr.

Lytton joined a group of suffragettes, including Jane Brailsford and Emily Wilding Davison, who resolved to undertake acts of violence in order to protest against forcible feeding. On 9th November 1909, she was arrested in Newcastle. She was sent to prison for 30 days. "Mrs. Brailsford, who had struck at the barricade with an axe, was also given the option of being bound over, which she, of course, refused, with the alternative of a month's imprisonment in the second division. We were put again into a van, but had only a short way to drive. We were shown into a passage of the prison where the Governor came and spoke to us. He was very civil, and begged us not to go on the hunger-strike." She did but as she pointed out in Prisons and Prisoners (1914) after a couple of days "the wardress came in and announced that I was released, because of the state of my heart!"

Constance Lytton was angry that she should be given special treatment and decided to adopt a false identity. After another demonstration Constance was arrested but this time she gave her name as Jane Wharton, a London seamstress. Constance was sentenced to fourteen days and when she refused to eat, she was forced fed eight times. When the authorities discovered Jane Wharton's true identity she was immediately released.

Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of his Batheaston estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest". Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay at Eagle House and the summer-house. In April 1910, Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary: "Linley and Annie Kenney brought Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence and Lady Constance from the station in a taxi-cab in time for lunch and they went to the meeting in the same way... Lady Constance showed how she was first prejudiced against militant methods till gradually step by step she found she must go to prison herself. I suppose future generations will give honour to these noble people. When the cause becomes the fashion, we shall have the stupid people in it."

In April 1910, Colonel Linley Blathwayt decided to create a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to Eagle House. During that month Constance Lytton, Annie Kenney, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Clara Codd, were all invited to tree planting ceremonies. On 22nd April, Constance planted a Cupressus Allumii in the suffragette arboretum.

On 12th June 1910 Lytton was appointed as a paid organizer of the WSPU with a salary of £2 a week, backdated six months. The salary enabled her to take a small flat, very close to that of Mary Neal, opposite Euston Station.

In November 1911 Constance Lytton was arrested for window-breaking but was released when it became clear that she was in danger of dying. Soon afterward Constance suffered a stroke which left her partly paralyzed. Now unable to take an active role in the suffragette struggle, Constance concentrated on writing articles and pamphlets on women's rights for the WSPU. Constance also wrote a book on her experiences in the suffragette movement called Prisons and Prisoners (1914).

When the WSPU ended their militant campaign in 1914, Lytton gave her support to Marie Stopes and her campaign to establish birth-control clinics. Lady Lytton totally disapproved of her daughter's political activities. However, she gave Constance the assistance she needed to write her books and nursed her daughter, who was now seriously ill.

Just before her death, Constance Lytton wrote to her aunt, Theresa Earle: "If it should happen… I am happy to die. If, as many people believe, we step into a higher life, but are again with loved companions who have died before, then it will be very good. Death to me is like a gentle lover…I am so tired of life, I should like to be taken in his sheltering arms and have an end… I have long hoped to die, and since I've seen this possible road, I have felt most wonderfully happy. Of late years I have seen and felt much of the sad side of death - the separation from those we love. Now I see the joyful side - the release from bodily ills - and it is restful beyond all words."

Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton died at Knebworth House on 2nd May 1923.

On this day in 1882 Alan Alexander Milne was born in Hampstead. His father was headteacher of Henley House School. One of his teachers was H. G. Wells who taught at the school between 1889-1890.

After leaving Henley House he attended Westminster School. A talented mathematician he won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge. While at university Milne edited the student magazine Granta. After leaving university he worked as a freelance writer until being appointed assistant editor of Punch Magazine in 1906. A collection of his magazine articles, The Day's Play, was published in 1910.

Milne was a pacifist but on the outbreak of the First World War he responded to the call by Lord Kitchener to join the British Army. Milne was offered a commission by the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in February 1915. After enduring basic training on the Isle of Wight he attended a course at Weymouth to become a signalling officer.

Second Lieutenant Milne was sent to the Western Front during the Somme Offensive. Soon after arriving on the front-line his best friend, Ernest Pusch, was killed: "just as he was settling down to his tea, a shell came over and blew him to pieces." His brother, Frederick Pusch, had been killed by a German sniper a few days later.

On 10th August 1916, Milne and four other men were sent out to run out telephone cable so that during forthcoming attack communications with battalion and brigade headquarters could be maintained. During the operation, the senior Signalling Officer, Kenneth Harrison, suffered a serious head wound from a shell splinter. Milne now took over from Harrison and the following night he laid another telephone line. As he later recalled: "elaborately laddered according to the text books, and guaranteed to withstand any bombardment".

The Commanding Officer of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Collison, admitted that the results of the preliminary bombardment: "Not only would it render the trench uninhabitable to our men, should they succeed in taking it, but it was plain intimation to the Hun that we contemplated some action against him in the near future."

On 12th August 1916, Milne's infantry platoon left the front-line trenches. The men made their attack behind a barrage that lifted as they went forward. Immediately they came under intense German machine gun fire. None of Milne's men got to within twenty yards (18.2m) of the German trench. The battalion lost around sixty killed, and just over a hundred wounded. Of the five officers who led the attack, three were killed and two severely wounded.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Collison wrote a report that claimed his men had died bravely: "I may mention that I saw no man lying otherwise than with his face to the enemy." Milne interpreted these events differently and later claimed that this attack changed his view of the war: "It makes me almost physically sick of that nightmare of mental and moral degradation."

In November 1916 Milne was moved to the much quieter trenches near Loos. However he contacted trench fever and he was evacuated to England. After his recovery he taught at a newly-established signalling school.

After the war Milne returned to Punch Magazine but his spent his spare time writing plays. The birth of his son, Christopher Robin, resulted in him writing some poems and stories for children. In 1924 he published a book of children's poems, When We were Very Young, that were illustrated by E. H. Shepard. The book included the first appearance of Winnie the Pooh.

In 1925 he bought Cotchford Farm in Hartfield. He was encouraged to write more children's stories and Winnie-the-Pooh was published in 1926. It was a great success and it was followed by The House at Pooh Corner in 1928. These stories took place in Posingford Wood close to Milne's home. Milne contined to write plays and novels but they failed to make him any money, unlike his children stories. Claire Tomalin has pointed out that "his fame as a children's writer made it increasingly difficult for him to interest public, critics or publishers in the other, more serious work."

In 1934 Milne published Peace With Honour about his experiences of the First World War. This was followed by It's Too Late Now: The Autobiography of a Writer (1939).

Milne served as a Captain of the Home Guard in Hartfield and Forest Row during the Second World War. However, his health was not good and in 1952 he suffered a stroke that left him as an invalid.

Alan Alexander Milne died at Cotchford Farm on 31st January 1956.

On this day in 1884 Arthur Ransome, the son of Cyril Ransome and Edith Boulton, was born at 6 Ash Grove, Headingley, Leeds. His parents had held strong liberal views in their youth. Cyril wrote to Edith just before they got married: "I like you to be independent and think for yourself. I know among weak conventional people it is assumed that wives think just like their husbands and it is thought so nice and so pretty, while I think it is simply degrading to one and demoralizing to the other."

However, Cyril Ransome, who was professor of history at Yorkshire College (later to become Leeds University), was a committed conservative by the time Arthur was born. Arthur was introduced to radical beliefs by his neighbour, Isabella Ford, a leading figure in the Independent Labour Party and a pioneer of women's trade unions. It was at her home that Arthur met Prince Peter Kropotkin.

Arthur Ransome had a difficult relationship with his father. Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009) has pointed out: "Professor Ransome had tried to teach his eldest son to swim by throwing him over the side of a boat, and had the pleasure of watching him sink like a stone... Ransome acknowledged that his father was motivated only by the best of intentions, but revealed in one anecdote after another how his early development was impeded by an imagination so much less joyful and fertile than his own that rebellion was all but inevitable. Following the disastrous swimming lesson, he had taken himself, using his own pocket money, to the Leeds public baths, where he taught himself the backstroke in secret, only to be told when announcing the fact at breakfast that he was a liar. When the feat was eventually proved in situ, his father relented, but Ransome never truly forgave the accusation. He liked to remember the incident whenever any aspersion was cast on his honesty."

Ransome was educated by private tutors before being sent to the Old College at Windermere. He disliked boarding school and did not do well in his studies. When he was ten his father broke his ankle. Arthur explained in his autobiography: "For a long time he walked with crutches, the foot monstrously bandaged. The doctors were slow in finding what had happened, probably because my father was so sure himself. In the end they found that he had damaged a bone and that some form of tuberculosis had attacked the damaged place. His foot was cut off. Things grew no better and his leg was cut off at the knee. Even that was not enough and it was cut off at the thigh."

Cyril Ransome intended to stand as the Conservative Party candidate for Rugby but he died in 1897 just before Arthur was due to start at Rugby School: "I walked alone behind my father's coffin which, carried by six of his friends of unequal height, lurched horribly on its way. As the earth rattled on the lid of the coffin I stood horrified at myself, knowing that with my real sorrow, because I had liked and admired my father, was mixed a feeling of relief. This did not last. After the funeral more than one of my father's friends thought it well to remind me that I was now the head of the family with a heavy responsibility towards my mother and the younger ones. And my mother, feeling that she had to fill my father's place and determined to carry out his wishes now as when he was alive, told me (though I knew only too well already) of my father's fears for my character and her hopes that from now on I would remember to set a good example to my brothers and sisters." Ransome later wrote: "I have been learning ever since how much I lost in him. He had been disappointed in me, but I have often thought what friends we could have been had he not died so young."

Ransome friends at Rugby included Morgan Philips Price, Richard H. Tawney, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Harry Ricardo and Edward Taylor Scott, the son of C.P. Scott. Ransome continued to underachieve at school but did develop a good relationship with his English teacher, W. H. D. Rouse: "My greatest piece of good fortune in coming to Rugby was that... I came at once into the hands of a most remarkable man whom I might otherwise never have met. This was Dr W.H.D. Rouse... He saw nothing wrong in my determination some day to write books for myself, and to the dismay of my mother did everything he could to help me."

At the age of seventeen Ransome was offered a job with Grant Richards, a twenty-nine year old publisher. His first cousin, Laurence Binyon, a promising poet, gave him a good reference. Edith Ransome met Richards and agreed that her son should work for the young publisher: "She called on Mr Richards and was charmed by him. His offer was accepted, and within a year of leaving Rugby, I had become a London office boy with a salary of eight shillings a week."

According to Roland Chambers, his biographer, "Ransome handled every sort of menial task: wrapping books, fetching staff lunches from the local public houses, filling in labels, checking invoices and saving on postage by delivering parcels on foot. Before he had been in London more than a few weeks he knew every bookshop in and around Soho... Since Richards's business was overstretched and understaffed, he was soon given more responsible work: calling in sample bindings, ordering paper, learning the bibliographic language so essential to his trade. But Ransome was not content to remain at the manufacturing and distributive end of the industry. He wanted to be a writer." Ransome moved to the Unicorn Press and worked closely with the writers Edward Thomas, John Masefield, Lascelles Abercrombie and Yone Noguchi. Another friend, Cecil Chesterton, was a convinced socialist and the two men attended meetings of the Fabian Society.

Ransome became friendly with William G. Collingwood, the author and artist and for many years a close associate of John Ruskin. Ransome spent time with two of Collingwood's daughters, Dora, Barbara and Ursula. On 3rd June 1904, Dora wrote in her diary: "Last Saturday Mr Ransome came to dinner. He is staying in the village and has been to dinner every day since. Today he has been on the water with us from 9 to 7 with an interval for lunch. This evening we stayed in the garden and he tried to make us see fairies."

Over the next few years Ransome "scratched a living" by writing stories and articles. His literary masters were William Morris, Thomas Carlyle and William Hazlitt. Morris and other Christian Socialists were especially important to him: "I read entranced of the lives of William Morris and his friends, of lives in which nothing seemed to matter except the making of lovely things and the making of a world to match them... From that moment I suppose, my fate was decided, and any chance I had ever had of a smooth career in academic or applied science was gone forever."

Ransome accepted several commissions from Henry J. Drane, the publisher of "Drane's ABC Handbooks". Priced at one shilling, Ransome contributed the ABC of Physical Culture. It included seven chapters "Exercises for General Health", "Muscular", "Breathing", "Smoking", "Food", "Drinking" and "Sleep". Other titles by Ransome included Highways and Byways in Fairyland, The Child's Book of the Seasons, Pond and Stream and Bohemia in London. Ransome was also commissioned to write a series of critical anthologies, The World Story Tellers, that would include his favourite authors.

Ransome hoped to marry Barbara Collingwood, but she turned him down. Next came her sister Dora, with equally painful results. Stephana Stevens also rejected him. According to Roland Chambers: "By 1908, virtually every woman of Ransome's acquaintance had either laughed or sighed as he protested his devotion. Some were gratifying flustered; others offered him tea. No serious offence was taken. But it was inevitable that at some point or another somebody would take him seriously, and when it happened, no one was more astonished than Ransome himself."

In early 1909 Ransome met Ivy Constance Walker in the flat rented by his friend, Ralph Courtney. Ransome later recalled: "She announced at once that she was not a barmaid, alluding, I suppose, to the impropriety of coming with young men to a young man's rooms... She had an extraordinary power of surrounding the simplest act with an air of conspiratorial secrecy and excitement." Ransome said he had fallen in love, "not happily, as with Barbara Collingwood, but in a horribly puzzled manner". Ivy told him that her mother was an unstable lunatic and her father was a sadist: "From all this fantastic horror I was to rescue her and I could see no other way before me." They married on 13th March 1909. A daughter, Tabitha, was born in 1910.

It was not a happy marriage and it did not help his writing career. Ransome wrote on 12th December, 1912: "This last year has been the worst of my life... I have not been able to work. I have allowed myself to keep my wife's times rather than my own. I have found it increasingly difficult to filch or force time for study of any kind. I have risen late, too late for a morning's work... In the evening, for fear of hearing my wife's complaint that I have been away from her all day and might at least spare her the evening, I have played cards (with her).... an ill conscience has made me ill-tempered and my wife unhappy. I have been unhappy almost always myself." Ransome's biographer, Roland Chambers, claimed his wife "shocked his Victorian sensibilities with her tantrums, her lewdness, and her longing for notoriety."

Ransome met Harold Williams and his wife, Ariadna Tyrkova, in Russia in 1914. Ransome later commented: "He (Williams) opened doors for me that I might have been years in finding for myself... I owe him more than I can say." People he was introduced to included Sir George Buchanan, Bernard Pares, Paul Milyukov and Peter Struve. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): Williams had a major influence on Ransome: "A shy, generous man a few years older than himself, with a pedagogic streak and a disarming stutter. Ransome benefited from Williams's encyclopedic knowledge of Russian history, his journalistic contacts and also from a friendship with Williams's wife, Ariadna Tyrkova, the first female representative elected to the Russian parliament, or State Duma, and a passionate advocate of constitutional reform. In Williams's company Ransome discussed not only politics, but philosophy, history and literature, sought out his advice on every subject and listened in amazement as he spoke in any one of the forty-two different languages used in Russia at that time."

Ransome was still in Russia when the First World War started in August 1914. He wrote to a friend: "The streets are full of soldiers. And, well, I always admired the Russians, but never so much as now. You know how our soldiers go off in pomp with flags and music. I have not heard a note of music since the declaration of war. They go off quite silently here in the middle of the night, carrying their little tin kettles, and for all the world like puzzled children going off to school for the first time. And the idea in all their heads is fine. They all say the same thing. We hate fighting. But if we can stop Germany then there will be peace for ever."

Arthur Ransome now returned to London where he hoped to find a newspaper willing to employ him to report on the war. In an article published on 3rd September 1914 where he predicted that at the end of the war: "England will be more English, France more French, and in the East, Russia will be more Russian and less inclined to suppose that civilization as well as the best of everything is made in Paris, London, Vienna and Berlin."

In December 1914 Ransome returned to Petrograd. Hamilton Fyfe, a journalist employed by the Daily Mail tried unsuccessfully to persuade the newspaper to send Ransome to report the war in Poland. Another friend, Harold Williams, arranged for Ransome to work for the Daily News. His first report on the Eastern Front appeared in the newspaper on 2nd September 1915.

The British government had established the secret War Propaganda Bureau on the outbreak of the First World War. Based on an idea put forward by David Lloyd George, the plan was to promoting Britain's interests during the war. This involved recruiting Britain's leading writers to write pamphlets that supported the war effort. Writers recruited included Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett, John Masefield, Ford Madox Ford, William Archer, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Parker, G. M. Trevelyan and H. G. Wells.

One of the first pamphlets to be published was Report on Alleged German Outrages, that appeared at the beginning of 1915. This pamphlet attempted to give credence to the idea that the German Army had systematically tortured Belgian civilians. The great Dutch illustrator, Louis Raemakers, was recruited to provide the highly emotionally drawings that appeared in the pamphlet.

Bernard Pares became aware of the activities of the secret War Propaganda Bureau and suggested to Robert Bruce Lockhart, the British consul-general that a similar organization should be set up in Russia to control reporting on the Eastern Front. Lockhart set up a meeting with British journalists, including Ransome, in January 1916. After talking to Harold Williams, Lockhart submitted a proposal to the British ambassador Sir George Buchanan. The project was approved and became known as the International News Agency (Anglo-Russian Bureau). Funded by the Foreign Office and headed by Hugh Walpole, it placed pro-British stories in Russian newspapers. As well as Ransome, Pares and Williams, other members included Hamilton Fyfe of the Daily News and Morgan Philips Price of the Manchester Guardian.

After visiting the Russian Army on the frontline Ransome reported: "Looking back now I seem to have seen nothing, but I did in fact see a great deal of that long-drawn-out front, and of the men who, ill-armed, ill-supplied, were holding it against an enemy who, even if his anxiety to fight was not greater than the Russians', was infinitely better equipped. I came back to Petrograd full of admiration for the Russian soldiers who were holding the front without enough weapons to go round. I was much better able to understand the grimness with which those of my friends who knew Russia best were looking into the future."

As Nicholas was supreme command of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline support for the Tsar Nicholas II in Russia. On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges."

After the abdication of Tsar in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Prince Lvov had always held aloof from a purely political life. He belonged to no party, and as head of the Government could rise above party issues. Not till later did the four months of his premiership demonstrate the consequences of such aloofness even from that very narrow sphere of political life which in Tsarist Russia was limited to work in the Duma and party activity. Neither a clear, definite, manly programme, nor the ability for firmly and persistently realising certain political problems were to be found in Prince G. Lvov. But these weak points of his character were generally unknown."

Ransome reported in the Daily News on 16th March 1917: "It is impossible for people who have not lived here to know with what joy we write of the new Russian Government. Only those who know how things were but a week ago can understand the enthusiasm of us who have seen the miracle take place before our eyes. We knew how Russia worked for war in spite of her Government. We could not tell the truth. It is as if honesty had returned. Today newspapers have reappeared, and their tone and even form are so joyful that it is hard to recognize them. They are so different from the censor-ridden mutes and unhappy things of a week ago. Every paper seems to be executing a war-dance of joy."

On May 1st, 1917, Ransome went on the streets of Petrograd to witness the first official holiday of the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II: "In all directions as far as I can see red flags are waving above the dense crowd, which leaves just room for the constantly passing processions. On either side of the processions, long strings of men and women walk along holding hands... the whole town is hung with flags, banners and inscriptions. A characteristic emblem, an enormous red and white banner, hangs over the granite front of the German embassy, which was sacked in 1914 and has stood empty ever since. The banner is inscribed, Proletariat of all lands unite. That is the thought in the minds of the Russian workmen today. When will such a day be seen in Berlin?"

Ransome also reported on the Kornilov Revolt: "Last night I saw the cavalry regiment just arrived from the front to support the Government riding from the station. Dnsty, sunburnt, with full equipment and gas masks swinging in cases at their sides distinguishing them from the troops at the rear, they moved through the streets on little grey horses. One man with his reins loose on his horse's neck played the accordion accompanied by another who beat time on a tambourine. They brought with them into the hot, damp July' evening in Petrograd something of the old vigour of the front; something of the vivid contrast there has always been between the front and the rear. I have never felt so strongly that Petrograd was a sick city as when I read the little dusty red flags fastened on their green lances. Here were the original watchwords of revolution: Long Live the Russian Republic, Forward in the Name of Freedom, Liberty or Death.

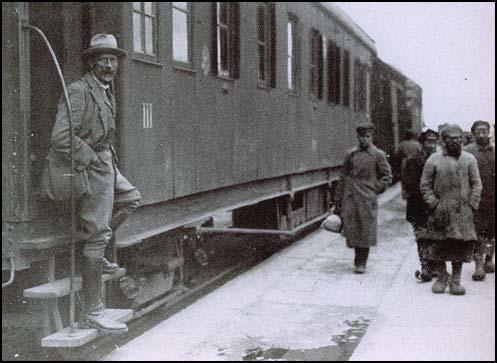

Lola Kinel met Ransome on a train during the summer of 1917. She later recalled in her autobiography, Under Five Eagles (1937) that "Ransome was an odd-looking man walking up and down the corridor and throwing occasional surreptitious glances in our direction. He was tall, dressed in a Russian military coat, though without insignia, and a fur cap. He had long red moustaches, completely concealing his mouth, and humorous, twinkling eyes." Ransome delighted her with his broken Russian and they spent the rest of the journey playing chess.

Kinel visited Ransome at his room in Glinka Street in Petrograd. "It was the first bachelor room I had ever seen; it had a desk and typewriter in one corner, in another a bed, night table, and dresser all behind a screen; then a sort of social arrangement, consisting of an old sofa and a round table with some chairs around it in the centre. And books. They were everywhere heaped on the sofa and even on the floor. Among these books I found occasionally torn socks. I used to pick them up gingerly in my gloved hand and wrap them in a piece of newspaper... His own Bohemianism was not a pose but seemed real. He had, I remember, a thorough contempt for men who dressed well, or the least conventionally. He forgave women if they were pretty, but he preferred most Russian women, who do not pose and are simple, to English girls. For England he seemed to have a queer mixture of contempt, dislike, and love. He was clever, yet childish, very sincere and kind and romantic, and on the whole far more interesting than his books."

George Alexander Hill, a British spy, met Ransome during this period and commented on him in his autobiography, Go Spy the Land (1933): "A tall, lanky, bony individual, with a shock of sandy hair, usually unkempt, and the eyes of a small inqquisitive and rather mischievous boy. He really was a lovable personality when you came to know him." In fact, he was in poor health at the time. He blamed the shortage of fruit and vegetables in his diet. He wrote to his mother: "I can't cross a room without nearly collapsing and the day before yesterday I fainted in the street.

Ransome was so ill that in October 1917 he left Russia. He was therefore in England when the Russian Revolution took place. Ransome wrote an article for the Daily News on 9th November. Ransome argued: "The lack of bloodshed during the Bolshevik coup d'état is due to two causes. First the comparative unanimity of the classes represented in the Soviet, and second to the fact that the large masses of the population increasingly despair of politics, and, though possibly disapproving, are willing to stand aside."

In a series of newspaper articles Ransome attempted to explain the Bolshevik government's attitude towards the First World War: "They do not want any peace which would leave Russia in the position of a sleeping partner of Germany. On the other hand, they are opposed to assisting what they regard as Imperialist war-aims on the part of ourselves. They will probably use their new position to press more insistently than their precursors for definition of Allied war-aims. If, however, we wish to force them into a more hostile attitude, and perhaps into a separate peace, we cannot do better than to follow the example of some of this morning's newspapers in loudly condemning what we do not understand."

Ransome argued that it was important to remember that Lenin and Bolsheviks had been successful because they had removed an unpopular government: "The most important thing to be remembered in estimating the present situation in Russia is that Bolshevism' is a tendency quite independent of the personality and doctrines of the Bolshevik leaders. When during the last few months in Petrograd we observed to each other that more and more people were turning Bolshevik, we meant not that they were embracing the principles of Socialism as expounded by Lenin, but simply that they were coming nearer to active and open hostility to the Government."

The British government disapproved of Ransome's articles. John Pollock of The Morning Post had already told the government that he believed Ransome was a Bolshevik sympathizer and a strong opponent of David Lloyd George: "In the summer of 1917 I met him in Petrograd, where he was publicly abusing the British government, and in particular Mr Lloyd George, for setting up tyranny in England... In the Autumn of 1917 I heard that he was in close touch with the Bolshevik leaders." Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette (2013) has commented that he was a Bolshevik sympathizer: "There was some truth in this. Ransome sincerely hoped that the Bolshevik revolution would sweep away the many injustices of the old regime and offer a brighter future to the country's downtrodden poor."

On 3rd December, 1917, Ransome went to see Sir Robert Cecil, the Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs. Ransome recorded in his diary: "He stood in front of the fireplace, immensely tall, fantastically thin, his hawk-like head swinging forward at the end of a long arc formed by his body and legs. 'If you find, as you well may, that things have collapsed into chaos, what do you propose to do?' I told him that I should make no plans until I could see for myself what was happening, and that from London I could make no guess in all that fog of rumour where to look for the main thread of Russian history. He gave me his blessing, and made things easy for me, at least as far as Stockholm, by entrusting the diplomatic bag to me to deliver to the Legation there."

Ransome was friends with Zelda Kahan, a member of the the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Her brother-in-law, Theodore Rothstein, was a close friend of Lenin and wrote a letter of introduction for Ransome that he could show the Bolshevik government. It included the following passage: "Mr Ransome is the only correspondent who has informed the English public of events in Russia honestly."

Armed with this letter he traveled to Stockholm and met Vatslav Vorovsky, the head of the Bolshevik legation. His interview with Vorovsky appeared in the Daily News on 19th December, 1917. Vorovsky reminded Ransome: "You have lived in Russia long enough to know that Russia is not a condition to carry on a war. Russia must make peace. It is for the Allies to choose whether that peace is to be a separate or a general peace." Vorovsky pointed out that the Bolshevik government's quarrel was not with the English working class, but only with the British government, which clung so obstinately to the destruction of Germany.

Ransome described Vorovsky as being "well-educated, amiable and cosmopolitan". He warned that "continual sabotage on the part of the bourgeoisie may exasperate the mass of the people to such an extent as to carry them beyond the control of their leaders." He then handed Ransome his visa and he was able to move on to Russia. Ransome arrived in Petrograd on 25th December, 1917.

Ransome first met Evgenia Shelepina when he interviewed Leon Trotsky on 28th December 1917. Shelepina was Trotsky's secretary. Ransome fell in love with Shelepina and the two became lovers. Ransome's biographer, Roland Chambers, has pointed out: "Over forty years later, Ransome remembered the decisive moment at which he realized he was in love: a mixture of terror and relief over which he had no power whatsoever. But as he snatched his future wife from beneath the wheels of history - the war, the Revolution, the fatal passage of circumstance which Lenin had declared indifferent to the fate of any single individual - the possibility of separating his private from his professional affairs remained as remote as ever."

Ransome's article on Leon Trotsky appeared in the Daily News on 31st December, 1917. "In an anteroom one of Mr Trotsky's secretaries, a young officer, told me Mr Trotsky was expecting me. Going into an inner room, unfurnished except for a writing table, two chairs and a telephone, I found the man who, in the name of the Proletariat, is practically the dictator of all Russia. He has a striking head, a very broad, high forehead above lively eyes, a fine cut nose and a small cavalier beard. Though I had heard him speak before, this was the first time I had seen him face to face. I got an impression of extreme efficiency and definite purpose. In spite of all that is said against him by his enemies, I do not think that he is a man to do anything except from a conviction that it is the best thing to be done for the revolutionary cause that is in his heart. He showed considerable knowledge of English politics."

The article quoted Trotsky as saying: "Russia is strong in that her Revolution was the starting point of a peace movement in Europe. A year ago it seemed that only militarism could end the war. It is now clear that the war will be decided by social rather than political pressure. It is to the Russian Revolution that German democracy looks, and it is the recognition of that fact that compels the German Government to accept the Russian principles as a basis for negotiation."

Ransome asked Trotsky if he considered Germany's peace offer as a joint victory of the Russian and German democracies. He replied, "Not of Russian and German democracy alone, but of the democratic movement generally. The movement is visible everywhere. Austria and Hungary are on the point of revolt, and not they alone. Every Government in Europe is feeling the pressure of democracy from below. The German attitude merely means that the German Government is wiser than most, and more realistic. It recognizes the real factors and is moved by them. The Germans have been forced by democratic pressure to throw aside their grandiose plans of conquest and to accept a peace in which there is neither conqueror nor conquered."

The article was read by the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour. He immediately telegramed the British Embassy in Petrograd and asked if Ransome could be recruited to provide his services as an unofficial agent, communicating British views to the Soviet and vive versa. Ransome agreed and reported directly to the British Ambassador, George Buchanan or Major Cudbert Thornhill of British intelligence.

Ransome's new girlfriend, Evgenia Shelepina, was a major source of secret information. Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013) commented that: "Their relationship was to transform the information he received from the regime: it was Shelepina who typed up Trotsky's correspondence and planned all his meetings. Suddenly, Ransome found himself with access to highly secretive documents and telegraphic transmissions."

Colonel Alfred Knox, the British Military Attaché at the embassy, had no idea that Ransome was working as a British agent. He was appalled by what he considered to be Ransome's pro-Bolshevik articles that were appearing in the Daily News and the New York Times. He suggested that Ransome should be "shot like a dog". Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009) argued: "Ransome's articles reflected the party line so accurately that there was little to choose between them but style, while as his relationship with Evgenia deepened, so any change of heart or sudden epiphany became that much more improbable. In his autobiography, she is pictured either as a distant functionary, handing out official releases, or as guardian of his personal happiness; never both at the same time. They had grown together gradually, as ordinary people do, strolling in the evenings, taking supper at the rooms she shared with her sister at the commissariat's headquarters in the centre of town."

Ransome developed a very intense relationship with Evgenia Shelepina and told her that as soon as he could arrange a divorce from Ivy Constance Ransome he would marry her. In his autobiography he recalled, that she had slipped when boarding a tram, and clutching the rail, was dragged full length along the track, so that if her grip had failed she would have been cut in two. "Those few horrible seconds during which she lay almost under the advancing wheel possibly determined both of our lives. But it was not until afterwards that we admitted anything of the kind to one another."

George Alexander Hill, a British diplomat in Petrograd, got to know Shelepina during this period. "She must have been two or three inches above six feet in her stockings... At first glance, one was apt to dismiss her as a very fine-looking specimen of Russian peasant womanhood, but closer acquaintance revealed in her depths of unguessed qualities.... She was methodical and intellectual, a hard worker with an enormous sense of humour. She saw things quickly and could analyse political situations with the speed and precision with which an experienced bridge player analyses a hand of cards... I do not believe she ever turned away from Trotsky anyone who was of the slightest consequence, and yet it was no easy matter to get past that maiden unless one had that something."

Ransome developed a close relationship with Karl Radek, who was the Bolshevik chief of Western propaganda. Ransome argued in his autobiography: "Radek had been born in Poland and spoke Polish (badly as his wife used to say, because he had talked too much German in exile), Russian (with a remarkably Polish accent) and French with the greatest difficulty. He always talked Russian with me but loved to drag in sentences from English books, which I sometimes annoyed him by being slow to recognize.... He had an extraordinary memory and an astonishingly detailed knowledge of English politics." Ransome celebrated the Russian New Year with the Radek family and Lev Sedov, the 12 year-old son of Leon Trotsky.

In January 1918, Ransome reported on the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. "I wonder whether the English people realize how great is the matter now at stake and how near we are to witnessing a separate peace between Russia and Germany, which would be a defeat for German democracy in its own country, besides ensuring the practical enslavement of all Russia. A separate peace will be a victory, not for Germany, but for the military caste in Germany. It may mean much more than the neutrality of Russia. If we make no move it seems possible that the Germans will ask the Russians to help them in enforcing the Russian peace terms on the Allies."

Ransome feared that Russia would face anarchy if the Bolsheviks were defeated in the Constituent Assemby elections. He wrote in The Daily News: "In five days' time the Constituent Assembly meets. It now seems probable that it will contain a majority against the Bolsheviks by some other necessarily weaker government which will offer the German generals an antagonist infinitely less dangerous to them than Trotsky. Efforts are being made to secure street demonstrations in the Constituent Assembly's favour. If these efforts are successful, the result will be anarchy, for which the Germans could wish nothing better."

Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17). As David Shub pointed out, "The Russian people, in the freest election in modern history, voted for moderate socialism and against the bourgeoisie."

Lenin was bitterly disappointed with the result as he hoped it would legitimize the Russian Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was elected President. Nikolai Sukhanov argued: "Without Chernov the SR Party would not have existed, any more than the Bolshevik Party without Lenin - inasmuch as no serious political organization can take shape round an intellectual vacuum. But Chernov - unlike Lenin - only performed half the work in the SR Party. During the period of pre-Revolutionary conspiracy he was not the party organizing centre, and in the broad area of the revolution, in spite of his vast authority amongst the SRs, Chernov proved bankrupt as a political leader. Chernov never showed the slightest stability, striking power, or fighting ability - qualities vital for a political leader in a revolutionary situation. He proved inwardly feeble and outwardly unattractive, disagreeable and ridiculous."

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia.

While he was in Petrograd he met Raymond Robins, the brother of Elizabeth Robins, a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union before the war. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): "On the day after the Trotsky interview, Ransome had dined with Colonel Raymond Robins, head of the American Red Cross, and Edgar Sisson, former editor of the Chicago Tribune. Robins, he concluded, was by far the superior specimen. As an evangelical Christian, an Alaskan gold prospector and straight-talking Chicago progressive, his politics were no more compatible with Bolshevism than those of Woodrow Wilson, whom he counted amongst his personal friends. But Robins had seen the Bolsheviks at work in the regional soviets. No other government, he believed, was capable of maintaining order at home while opposing German interests. If the Allies wanted an Eastern Front, they should supply the money and arms. If they wanted peace, it would have to be a general peace. By the time Ransome returned to Petrograd, Robins was on excellent terms with Trotsky and Lenin, whom he considered men of courage and integrity." Ransome later recalled that Robins told him that Leon Trotsky was "four times son of a bitch, but the greatest Jew since Jesus."

On 25th April, 1918, Ransome had dinner with Robins. The two men agreed that the Soviet government would survive and that Western governments should not attempt to overthrow it. Ransome argued that he had written a pamphlet with Karl Radek, entitled On Behalf of Russia: An Open Letter to America. Robins, who was just about to leave for home, agreed to use his influence to get it published by The New Republic magazine.

The pamphlet was published in July 1918. It included the following passage: "These men who have made the Soviet government in Russia, if they must fail, will fail with clean shields and clean hearts, having, striven for an ideal which will live beyond them. Even if they fail, they will none the less have written a page in history more daring, than any other which I can remember in the history of humanity. They are writing it amid the slinging of mud from all the meaner spirits in their country, in yours and in my own. But when the thing is over, and their enemies have triumphed, the mud will vanish like black magic at noon, and that page will he as white as the snows of Russia, and the writing on it as bright as the gold domes I used to see glittering in the sun when I looked from my window in Petrograd."

Lenin was shot by Dora Kaplan, a member of the Socialist Revolutionaries, on 30th August, 1918. Two bullets entered his body and it was too dangerous to remove them. Kaplan was soon captured and in a statement she made to Cheka that night, she explained that she had attempted to kill him because he had closed down the Constituent Assembly. In a statement to the police she confessed to trying to kill Lenin. "My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot at Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution. I was exiled to Akatui for participating in an assassination attempt against a Tsarist official in Kiev. I spent 11 years at hard labour. After the Revolution, I was freed. I favoured the Constituent Assembly and am still for it."

On 2nd September, as Lenin's life hung in the balance, Ransome wrote an obituary hailing the founder of Bolshevism as "the greatest figure of the Russian Revolution". Here "for good or evil was a man who, at least for a moment, had his hand on the rudder of the world". Common peasants who had known Lenin attested to his goodness, his extraordinary generosity to children. The workers looked up to him, "not as an ordinary man, but as a saint". Without Lenin, Ransome concluded, the soviets would not perish, but they would lose their vital direction. His influence was the one constant steadying factor. He had his definite policy, and his firmness in his own position was the best curb on other, more mercurial people. In the truest sense of the word it may be said that the revolution has lost its head. Fiery Trotsky, ingenious, brilliant Radek, are alike unable to replace the cool logic of the most colossal dreamer that Russia produced in our time."

Lenin eventually recovered and the two men met several times to discuss politics. Ransome later wrote: "Not only is he without personal ambition, but, as a Marxist, believes in the movement of the masses... His faith in himself is the belief that he justly estimates the direction of elemental forces. He does not believe that one man can make or stop the revolution. If the revolution fails, it fails only temporarily, and because of forces beyond any man's control. He is consequently free, with a freedom no other great leader has ever had... He is as it were the exponent not the cause of the events that will be for ever linked with his name."

Ransome told Lenin that a Marxist revolution was unlikely to take place in Britain. Lenin replied: "We have a saying that a man may have typhoid while still on his legs. Twenty, maybe thirty years ago, I had abortive typhoid, and was going about with it, had it some days before it knocked me over. Well, England and France and Italy have caught the disease already. England may seem to you untouched, but the microbe is already there."

After the assassination attempt on Lenin the authorities became more hostile to foreigners living in Russia. Ransome was warned by Karl Radek that his life would be in danger if the British government continued to give help to the White Army in the Russian Civil War. Ransome contacted his spymaster, Robert Bruce Lockhart, to help him and Evgenia Shelepina, to escape from Russia to Estonia by providing the necessary papers. Ransome promised to maintain contact with the Bolshevik leaders so he could keep the British government informed of their activities.

Lockhart agreed and sent a telegram to the Foreign Office in London in June 1918 asking for help. "A very useful lady, who has worked here in an extremely confidential position in a government office desires to give up her present position... She has been of the greatest service to me and is anxious to establish herself in Stockholm where she would be at the centre of information regarding underground agitation in Russia... In order to enable her to leave secretly, I wish to have authority to put her to Mr Ransome's passport as his wife and facilitate her departure via Murmansk." Arthur Balfour, the Foreign Secretary, arranged for the papers to be sent to Russia.

Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka, the Russian Secret Police, announced a few days later the start of the Red Terror: "We stand for organised terror, this must be clearly understood. Terror is an absolute necessity during times of revolution. Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government and the new order of life. Among such enemies are our political adversaries, as well as bandits, speculators and other criminals who undermine the foundations of the Soviet Government. To these we will show no mercy."

Ransome arrived in Stockholm on 5th August, 1918. He was being monitored by MI6. A telegram arrived at the War Office on 29th August that stated: "Arthur Ransome is reported to be in Stockholm, having married Trotsky's secretary, with a large amount of Russian Government money, and to be travelling with a Bolshevik passport. The alleged marriage we understand to be a put up job and so the Bolshevik passport may be of little account, but the fact that he has a large amount of Russian Government money is of interest to us, and we would like to have him watched accordingly. Could you please wire out."

On 2nd September, 1918, Bolshevik newspapers splashed on their front pages the discovery of an Anglo-French conspiracy that involved undercover agents and diplomats. One newspaper insisted that "Anglo-French capitalists, through hired assassins, organised terrorist attempts on representatives of the Soviet." These conspirators were accused of being involved in the murder of Moisei Uritsky and the attempted assassination of Lenin. Head of Special Mission to the Soviet Government, Robert Bruce Lockhart and Sidney Reilly were both named in these reports. "Lockhart entered into personal contact with the commander of a large Lettish unit... should the plot succeed, Lockhart promised in the name of the Allies immediate restoration of a free Latvia."

An edition of Pravda declared that Lockhart was the main organiser of the plot and was labelled as "a murderer and conspirator against the Russian Soviet government". The newspaper then went on to argue: "Lockhart... was a diplomatic representative organising murder and rebellion on the territory of the country where he is representative. This bandit in dinner jacket and gloves tries to hide like a cat at large, under the shelter of international law and ethics. No, Mr Lockhart, this will not save you. The workmen and the poorer peasants of Russia are not idiots enough to defend murderers, robbers and highwaymen."

The following day Lockhart was arrested and charged with assassination, attempted murder and planning a coup d'état. All three crimes carried the death sentence. The couriers used by British agents were also arrested. Lockhart's mistress, Maria Zakrveskia, who had nothing to do with the conspiracy, was also taken into custody. Xenophon Kalamatiano, who was working for the American Secret Service, was also arrested. Hidden in his cane was a secret cipher, spy reports and a coded list of thirty-two spies. However, Sidney Reilly, George Alexander Hill, and Paul Dukes had all escaped capture and had successfully gone undercover. It is not known if Arthur Ransome had been aware of this plot to overthrow the Bolsheviks.

The start of the Red Terror changed attitudes towards Arthur Ransome in the United States. Ambassador David R. Francis reported to President Woodrow Wilson that Ransome was closely linked to Karl Radek, one of the key leaders in the Bolshevik government. Ransome's On Behalf of Russia: An Open Letter to America was attacked by the American media and it was stated that the pamphlet was being distributed to Allied troops fighting in the Russian Civil War. The New York Times denounced Ransome as being the "mouthpiece of the Bolsheviki" and announced that they would no longer be publishing his articles in their newspaper.

On 12th September, 1918, a MI6 agent in Stockholm sent a report to headquarters about Ransome: "I do not know how much is known in London of Arthur Ransome's activities here, but it certainly ought to he understood how completely he is in the hands of the Bolsheviks. He seems to have persuaded the Legation that he has changed his views to some extent but this is certainly not the case. He claims, as has already been reported to you, to be the official historian of the Bolshevik movement. I suppose this is true, at all events it is true that he is living here with a lady who was previously Trotsky's private secretary, that he spends the greater part of his time in the Bolshevik Legation, where he is provided with a typewriter, and that he is very nervous as to the effect which his present attitude and activities may have upon his prospects in England. I also know that he has informed two Russians that I, personally, am an agent of the British Government, and said that he had this information from authoritative sources, both British and Bolshevik.

Ransome then received information that Horatio Bottomley, the editor of John Bull Magazine, was threatening to expose him as a Bolshevik spy. Ransome immediately contacted his spymaster in Russia, Robert Bruce Lockhart, and told him that Bottomley intended to describe him as a "paid agent of the Bolsheviks" and asked him for help. He pointed out that he had been asked by Sir George Buchanan to be "an intermediary to ask Trotsky certain questions, my attempts to get into as close touch as possible with the Soviet people have had the full approval of the British authorities on the spot. I have never taken a single step without first getting their approval."

Ransome went onto argue that he was under orders to provide pro-Bolshevik reports: "As for my attitude towards (the Bolsheviks), please remember that you yourself suppressed a telegram I wrote on the grounds that its criticism of them would have put an end to my good relations with them and so have prevented my further usefulness. Altogether, it will be very much too much of a good thing if, after having worked as I have, and been as useful as I possibly could, I am now to be attacked in such a way that I cannot defend myself except by a highly undesirable exposition (to persons who have no right to know) of what, though not officially secret service work (because I was unpaid) amounted to the same thing." Lockhart contacted Bottomley and the article never appeared.

In March 1919 Ransome arrived back in London. On 4th April he was arrested by the police under the terms of the Defence of the Realm Act. Ransome was interviewed by Sir Basil Thomson, Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. Ransome later recalled: "I was shown into Sir Basil Thomson's room and asked to sit down in the famous chair where so many criminals had sat before me." After being interviewed by Thompson he was released. Thompson told William Cavendish Bentinck that he was "satisfied that he is not a Bolshevik in the sense" Morgan Philips Price is.

Thompson wrote: "Ransome... thinks if something is not done soon, Russia will slip into a state of anarchy, which will be far worse than the present situation. He appears to have been very closely in touch with all the Bolshevik leaders, and is perfectly frank about what they told him. I think myself that we shall he able to restrain him from bursting into print. He wants to go into the country for six months to write a hook. All he wants to be allowed to put into print for the moment is a description of the ceremony of the International, which must have been very funny."

The following day Ransome was interviewed by Reginald Leeper, of the Political Intelligence Department. He was less convinced than Thompson about the dangers that Ransome posed: "After four hours' conversation with Ransome I believe he can do more harm in this country than even Price. Lenin would not have wasted two hours with him unless he thought he could be most useful to him here. What Lenin wants in England just now are people who will take up his policy and at the same time declare they are anti-Bolsheviks. Ransome will do this to perfection, if not by writing, then at least by talking to people."

Sir Basil Thomson, who now understood the work that Ransome had been doing for the government, over-ruled Leeper. He also gave permission for Evgenia Shelepina to enter the country. Ransome wrote to Evgenia with the news: "I have at last with great difficulty obtained permission for you to join me here in England... Do not delay for a minute... I am spending the whole time here working on my book and I am waiting for you to arrive." However, the Bolshevik government would not allow her to leave and Ransome realised he would need to go back to Russia to get her.

Adam Mars Jones has argued: "Ransome knew which side his bread was buttered on, though he may not have realised how busily it was being buttered on both sides, by British and Bolshevik agencies alike. He was nothing as complicated as a double agent, but was useful to each side only if he had some standing with the other." Sir Cavendish-Bentinck reported to the Foreign Office: "He (Ransome) is really rather a coward and is trying to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds."

While in England he wrote Six Weeks in Russia (1919), an account of the revolution and an explanation for the signing of the Brest-Litovsk. It sold over 8,000 copies in a fortnight. It was generally well-received and only The Times Literary Supplement offered any criticism. It accepted that Ransome "had been rigorous in seeking out both Bolsheviks and their socialist opponents, had not posed a single question or queried a single answer in a way that deviated from the official Soviet line."

One man who really liked the book was C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian. He offered him £1,000 a year, excluding travel expenses, to work for his newspaper, as its correspondent in Russia. Ransome immediate accepted the offer and told Scott that because of his Bolshevik contacts would be of help to British citizens in the country: "Except under a Trotsky regime I think I could probably be of use to British subjects in Russia, should any of them get into difficulties or want to get out."

Scott now applied to the Foreign Office for permission to send Ransome to Russia. However, he had made some powerful enemies in authority who did not know he had been working for MI6. However, Colonel Norman Thwaites of the War Office who had good connections to the intelligence community wrote: "Mr. Ransome is a man chiefly interested in himself and the lady referred to. He is without conviction or morality. He has always sided with the winning party, and his communications will be an indication of the strength of the Bolsheviks... I should certainly recommend his being allowed back into Russia."