On this day on 5th July

On this day in 1835 Ursula Mellor, the daughter of Joseph Mellor, was born on 5th July, 1835. Little is known of her early life but it was claimed that she was "a strong generous soul, very direct, simple as a child in some ways, yet with a keen brain and fine judgment".

On 13th September, 1855, Ursula married Jacob Bright, who worked for the family firm, John Bright & Brothers. Bright was deeply involved in radical politics and supported the Chartist movement. Over the next few years she gave birth to five children. Two of the boys died of diphtheria.

The family moved to Manchester "where Bright developed his commercial interests, not only in cotton spinning and carpets, but also in pioneering the introduction of the linotype machine into Britain". The couple continued to be involved in radical politics and campaigned for the parliamentary franchise to both men and women.

In October 1865, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy established the Manchester Committee for the Enfranchisement of Women. She gained the support of local radical members of the Liberal Party that included Ursula and Jacob Bright. Another active member included Richard Pankhurst,

In November 1867, Jacob Bright was elected to represent Manchester in the House of Commons. Bright now joined forces with John Stuart Mill, another supporter of women's suffrage. In a debate on the 1867 Reform Act, Mill proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

Mill lost his Commons seat in 1868, and Bright became leader of the suffragists in parliament, and took charge of the Women's Disabilities Removals Bill. In 1870 Bright and Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke introduced what was the first women's suffrage bill. After its defeat he introduced another Women's Suffrage Bill in 1871. Once again, William Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Party, arranged for it to be defeated and commented that women voting in elections would be "a practical evil of an intolerable character".

In 1870 Ursula Bright joined with Josephine Butler and Elizabeth Wolstenholme in forming the Ladies' National Association, an organisation that pressed for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. This legislation allowed policeman to arrest prostitutes in ports and army towns and bring them in to have compulsory checks for venereal disease. If the women were suffering from sexually transmitted diseases they were placed in a locked hospital until cured. It was claimed that this was the best way to protect men from infected women. Many of the women arrested were not prostitutes but they still were forced to go to the police station to undergo a humiliating medical examination.

Ursula Bright was a member of the executive committee of the Married Women's Property Committee for fourteen years. The passing of the 1882 Married Women's Property Act was acknowledged to have been due to her efforts. Elizabeth Cady Stanton noted "for ten consecutive years she gave her special attention to this bill… was unwearied in her efforts, in rolling up petitions, scattering tracts, holding meetings".

Under the terms of the act married women had the same rights over their property as unmarried women. This act therefore allowed a married woman to retain ownership of property which she might have received as a gift from a parent. Before the 1882 Married Women's Property Act was passed this property would have automatically have become the property of the husband.

Ursula Bright was interested in the abolition of the House of Lords, opposed compulsory vaccination, and had a wide circle of friends, both artistic and political, on both sides of the Atlantic. She was also a close friend of Annie Besant and in 1898 gave £3,000 to the Theosophical headquarters in northern India.

Ursula Bright died on 12th March 1915 at her home at 82 Drayton Gardens, Kensington, London.

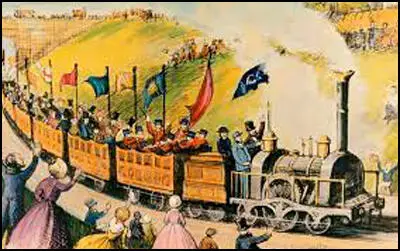

On this day in 1841 Thomas Cook organises his first package excursion. Cook had the idea of arranging an eleven-mile rail excursion from Leicester to a Temperance Society meeting in Loughborough on the newly extended Midland Railway. Cook charged his customers one shilling and this included the cost of the rail ticket and the food on the journey. The venture was a great success and Cook decided to start his own business running rail excursions. Cook later recalled that this was "the starting point of a career of labour and pleasure which has expanded into … a mission of goodwill and benevolence on a grand scale".

Cook set up as a bookseller and printer in Leicester. He specialized in temperance literature but also produced books aimed at a local market such as the Leicester Almanack (1842) and Guide to Leicester (1843). He also opened up temperance hotels in Derby and Leicester and continued to organize excursions. The author of Thomas Cook: 150 Years of Popular Tourism (1991) has pointed out: "In 1845, having won a reputation as an entrepreneur who could obtain cheap rates from the railway companies for large parties, he undertook his first profit-making excursion - to Liverpool, Caernarfon, and Mount Snowdon. Cook wrote a handbook which resembled in essential respects the modern tour operator's brochure."

In 1846 Cook took 500 people from Leicester on a tour of Scotland that involved visits to Glasgow and Edinburgh. One of his greatest achievements was to arrange for over 165,000 people to attend the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851. With the profits from his travel business Cook was able to "abandon the printing trade, give considerable sums to poor relief, promote the erection of a Temperance Hall in Leicester, and finance the rebuilding of his Commercial and Family Temperance Hotel". These were very popular and with the profits from his travel business Cook was able to "abandon the printing trade, give considerable sums to poor relief, promote the erection of a Temperance Hall in Leicester, and finance the rebuilding of his Commercial and Family Temperance Hotel".

Cook's travel business was badly damaged in 1862 when the Scottish railway companies refused to issue any more group tickets for Cook's popular tours north of the border. Cook now decided to take advantage of new rail links for the conveyance of large numbers of tourists to the continent. In his first year he arranged for 2000 visitors to travel France and 500 to Switzerland. In 1864 Cook began taking tourists to Italy.

Cook's tours of Europe, resulted in him being described as the "Napoleon of Excursions". However, he had his critics. Charles Lever, writing in Blackwood's Magazine, commented that Cook was guilty of swamping Europe with "everything that is low-bred, vulgar and ridiculous". Others complained about the bad taste of taking tourists to the battlefields of the American Civil War.

Cook moved his business to London. His son John managed the London office of the company that was now known as Thomas Cook & Son. John helped to expand the company by opening offices in Manchester, Brussels, and Cologne. In 1869 the company arranged tours of Egypt and the Holy Land, something he described as "the greatest event of my tourist life".

Thomas Cook had a difficult relationship with his son and only made him a partner in 1871. The author of Thomas Cook: 150 Years of Popular Tourism (1991) has suggested: "His reluctance was probably due to disputes between the two men, mainly over financial matters. Unlike Thomas, John believed that business should be kept separate from religion and philanthropy. He also upset his father by being more adventurous in investing money. He opened a hotel at Luxor and refurbished the Nile steamers of the khedive, from whom he obtained the passenger agency, thus helping to make Egypt a safer and more attractive destination."

By 1872 Thomas Cook & Son was able to offer a 212 day Round the World Tour for 200 guineas. The journey included a steamship across the Atlantic, a stage coach from the east to the west coast of America, a paddle steamer to Japan, and an overland journey across China and India.

Thomas continued to disagree with his son about the way the company should be run. After a serious dispute in 1878, Thomas decided to retire to Thorncroft, the large house which he had built on the outskirts of Leicester, and allow John Cook to run the business on his own.

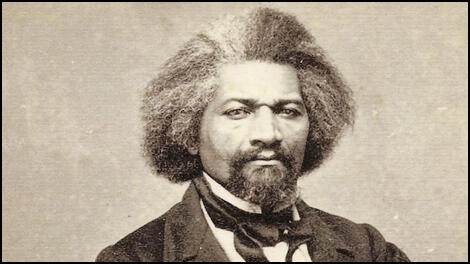

On this day in 1852 Frederick Douglass delivers his "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"

What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?...What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim....

You profess to believe, "that, of one blood, God made all nations of men to dwell on the face of all the earth," and hath commanded all men everywhere to love one another; yet you notoriously hate (and glory in your hatred) all men whose skins are not colored like your own.

On this day in 1857 Clara Eissner, the daughter of Gottfried Eissner, a local schoolmaster, was born in Wiederau, Saxony. While studying at Leipzig Teacher's College for Women she became a socialist and feminist.

In 1875 August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht, the founders of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP), merged it with the General German Workers' Association (ADAV), an organisation led by Ferdinand Lassalle, to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Clara was one of those who joined the new party. In the 1877 General Election in Germany the SDP won 12 seats. This worried Otto von Bismarck, and in 1878 he introduced an anti-socialist law which banned SDP meetings and publications.

Clara, like other members of the SDP left for Zurich in 1882 and then moved on to live in exile in Paris. During this period Clara read Woman and Socialism. In the book August Bebel argued that it was the goal of socialists "not only to achieve equality of men and women under the present social order, which constitutes the sole aim of the bourgeois women's movement, but to go far beyond this and to remove all barriers that make one human being dependent upon another, which includes the dependence of one sex upon another." She later wrote that out of this book "streams of life poured forth; thus it was that his great firmness in principles and tactics did not appear as dry, rigid dogmatism, but seemed, on the contrary, to breathe forth the natural freshness of life itself."

A strong supporter of international socialism, Clara married Ossip Zetkin, a Russian revolutionary who was living in exile. Ossip was a carpenter, a Marxist, and according to her mother was a "good-for-nothing". In 1883, her son Maxim, was born, followed by Kostya in 1885. In Paris she met other leading socialists from France, Germany and Russia. She was active politically, worked as a journalist and took up a role of "teacher and Educator".

Clara and Ossip Zetkin became members of the international socialist group, Cercle Internationale, which met weekly to discuss questions of Marxist theory and to plan action. "Here the Zetkins came into contact not only with Russian, German and French socialists, but with socialists from Spain, Italy, Austria and Britain as well. It was in this period that Clara Zetkin gained her vast knowledge of the international labour movement, as well as her proficiency in a number of languages." Ossip Zetkin died of tuberculosis in January, 1889.

Ossip Zetkin died of tuberculosis in January, 1889. Clara continued with her political campaigns. She refused to join the Berlin Association of Proletarian Women and Girls because it accepted only women as members. Clara disapproved of the "segregation of women and men" and regretted the "feminist tendencies... of many outstanding supporters of the Berlin movement". Zetkin was initially critical of the demand for female suffrage because "without economic freedom it changes absolutely nothing". She saw it as being a middle-class movement.

Clara Zetkin took a particular interest in supporting women workers in their demand for higher wages: "What made women's labour particularly attractive to the capitalists was not only its lower price but also the greater submissiveness of women. The capitalists speculate on the two following factors: the female worker must be paid as poorly as possible and the competition of female labour must be employed to lower the wages of male workers as much as possible. In the same manner the capitalists use child labour to depress women's wages and the work of machines to depress all human labour."

On this day in 1898 Richard Pankhurst died. For several years he had suffered from gastric ulcers. "Faithful and True My Loving Comrade", a quote from Walt Whitman, were the words Emmeline Pankhurst choose for his gravestone.

Richard Pankhurst, the son of an auctioneer, was born in Stoke in May 1834. Richard's father had originally been a member of the Church of England and the Conservative Party, but eventually become a Baptist and supporter of the Liberal Party. As a youth Richard taught at Baptist Sunday School in Manchester but later he became an agnostic.

Pankhurst was educated at Manchester Grammar School and the University of London. He graduated in 1858 and after a period at Lincoln's Inn qualified as a barrister. Pankhurst joined the Liberal Party and was active in the campaign for social reform. A supporter of free secular education for all, he started evening classes for working class people at Owens College in Manchester.

As a barrister, Pankhurst took a strong interest in legal reform. He was especially interested in changing those laws that discriminated against women. Pankhurst was legal adviser to Lydia Becker and the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage. In 1869 he drafted the amendment which included women in the Municipal Corporation Bill. The following year he was responsible for drafting the first bill for the enfranchisement of women ever presented to Parliament. Pankhurst also wrote the Married Women's Property Act of 1870, although it was much altered after it went through Parliament.

In 1879 Pankhurst married Emmeline Goulden. The couple had five children, including Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst, who were later to play a prominent role in the WSPU. Pankhurst remained involved in the struggle for women's rights and in 1882 drafted the Married Women's Property Act.

Pankhurst continued to be active in the Liberal Party until 1883 when he resigned over policy issues. Later that year he was an Independent candidate for a by-election in Manchester. Pankhurst's campaigned on a radical programme that included universal adult suffrage, payment of salaries for MPs, Disestablishment of the Church of England, free compulsory elementary education, Irish Home Rule, land nationalization and the abolition of the House of Lords. He was defeated in the election by 18,188 to 6,216.

In 1885 the Pankhurst family moved to London. He became friends with leading radicals in the capital including William Morris, Tom Mann, Eleanor Marx and Annie Besant. In 1885 he spoke on the same platform as Helen Taylor. His daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst, later revealed that her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, was disturbed by the fact that she wore trousers during the meeting: "Mrs Pankhurst was distressed that her husband should be seen walking with the lady in this garb, and feared that his gallantry in doing so... would cost him many votes."

Pankhurst joined the Fabian Society and played a leading role in the protest against police behaviour during the events of Bloody Sunday in 1887. During these years Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst continued their involvement in the struggle for women's rights and in 1889 helped form the pressure group, the Women's Franchise League. The organisation's main objective was to secure the vote for women in local elections.

In 1893 Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst returned to Manchester where they formed a branch of the new Independent Labour Party (ILP). In the 1895 General Election, Pankhurst stood as the ILP candidate for Gorton, an industrial suburb of the city, but was defeated.

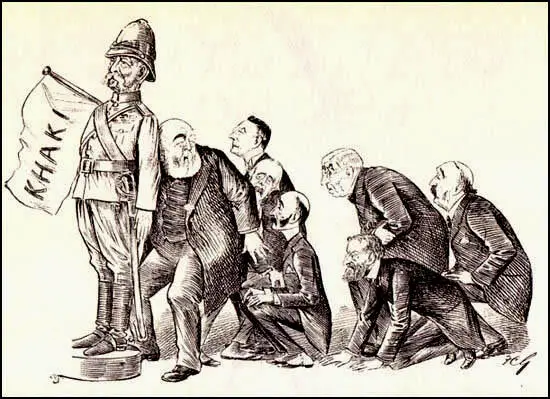

On this day in 1900, David Lloyd George is physically attacked at a meeting in Liskeard because of his opposition to the Boer War. Around fifty "young roughs stormed the platform and occupied part of it, while a soldier in khaki was carried shoulder-high from end to end of the hall and ladies in the front seats escaped hurriedly by way of the platform door." Lloyd George tried to keep speaking and it was only when some members of the audience began throwing chairs at him that he left the hall.

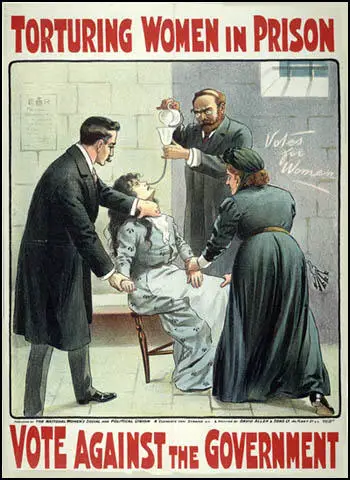

On this day in 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop begins the first Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU) hunger strike. On 25th June 1909, Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

Christabel Pankhurst claimed that this strategy had not been agreed by the organisation: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded."

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. When the doctor asked her what she was going to eat, she replied: "My determination". He answered: "Indigestible stuff, but tough no doubt." Herbert Gladstone, the Home Secretary, was consulted and he told the governor of the prison that "she should be allowed to die."

However, on reflection, they thought that if this happened, Dunlop might become a martyr and after ninety-one hours she was suddenly set free. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London’s Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail".

On 22nd September 1909, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh were arrested while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. Marsh, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

Keir Hardie, the Labour MP, protested against the idea of force-feeding in the House of Commons. However, his comments were greeted with a chorus of laughter and jeers. One newspaper reported: "Most of us desire something or other which we have not got... but we do not therefore take hatchets and wreck people's houses, or even shriek hysterically because the whole course of government and society is not altered to give us what we seek. These notoriety-hunters have effectually discredited the movement they think to promote."

Hardie wrote to The Daily News to complain about the way these women were being treated: "Mr. Masterman, speaking on behalf of the Home Secretary, admitted that some of the nine prisoners now in Winston Green Gaol, Birmingham, had been subjected to 'hospital treatment', and admitted that this euphemism meant administering food by force. The process employed was the insertion of a tube down the throat into the stomach and pumping the food down. To do this, I am advised, a gag has to be used to keep the mouth open. That there is difference of opinion concerning the horrible brutality of this proceeding? Women worn and weak by hunger, are seized upon, held down by brute force, gagged, a tube inserted down the throat, and food poured or pumped into the stomach. Let British men think over the spectacle".

C. P. Scott wrote to Asquith and Gladstone complaining of the "substantial injustice of punishing a girl like Miss Marsh with two months hard labour plus forcible feeding." As the editor of the Manchester Guardian, a newspaper that supported the Liberal Party, he suggested that the women should be released "to prevent the damage which is being done to our party". As a result of this letter, Gladstone agreed to monitor the health of the prisoners with a view to recommending an early release.

Mary Leigh, described what it was like to be force-fed: "On Saturday afternoon the wardress forced me onto the bed and two doctors came in. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternative days. The sensation is most painful - the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down - about a pint of milk... egg and milk is sometimes used." Leigh's graphic account of the horrors of forcible feeding was published while she was still in prison. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her.

Charlotte Marsh also experienced force-feeding. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000): "The Prison Visiting Committee reported that at first she (Charlotte Marsh) had to be fed by placing food in the mouth and holding the nostrils, but that she later took food from a feeding cup." Votes for Women, on her release, reported that Marsh had been fed by a feeding tube 139 times.

The authorities believed that force-feeding would act as a deterrent as well as a punishment. This was a serious miscalculation and in many ways it had the opposite effect. Militant members of the WSPU now had beliefs as strong as any religion and now they could argue that women were actually being tortured for their faith. "Suffragettes submitted to force-feeding as a way to express solidarity with their friends as well as to further the cause."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, one of the early hunger-strikers pointed out that if the government was so naive as to think "the nasal tube or the stomach pump, the steel gag, the punishment cell, handcuffs and the straight jacket would break the spirit of women who were determined to win the enfranchisement of their sex, they were again woefully misled". (12)The WSPU did get the support of two prominent journalists, Henry N. Brailsford and Henry Nevinson, who both resigned from The Daily News in protest against its refusal to condemn forcible feeding.

Christabel Pankhurst now used the WSPU newspaper, Votes for Women, to advocate the hunger-strike. "The spiritual force which they are exerting is so great that prison walls are rent, prison gates forced open, and they emerge free in body as they have never for an instant ceased to be... Those who, in these latter days, are privileged to witness this triumph of the spiritual over the physical, understand the true meaning and manner of the miracles of old times."

Christabel was also responsible for persuading 116 doctors to sign a letter sent to Henry Asquith, the new prime minister, protesting against artificial feeding. "We submit to you, that this method of feeding when the patient resists is attending with the gravest risks, that unforeseen accidents are liable to occur, and that the subsequent health of the person may be seriously injured. In our opinion this action is unwise and inhumane. We therefore beg that you will interfere to prevent the continuance of this practice."

On 8th October, 1909, Christabel had a meeting with leading militants, Constance Lytton, Jane Brailsford, Emily Wilding Davison, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney and Kitty Marion. who resolved to undertake acts of violence in order to protest against forcible feeding. "There were twelve women... all intending stone-throwers, and Christabel was there to hearten us up and go into details about the way in which we were to do it."

The women sent a letter to The Times explaining what they intended to do: "We want to make it known that we shall carry on our protest in our prison cells. We shall put before the Government by means of the hunger-strike four alternatives: to release us in a few days; to inflict violence upon our bodies; to add death to the champions of our cause by leaving us to starve; or, and this is the best and only wise alternative, to give women the vote. We appeal to the Government to yield, not to the violence of our protest, but to the reasonableness of our demand, and togrant the vote to the duly qualified women of the country. We shall then serve our full sentence quietly and obediently and without complaint. Our protest is against the action of the Government in opposing woman suffrage, and against that alone. We have no quarrel with those who may be ordered to maltreat us".

On 9th November 1909, Lady Lytton, was arrested in Newcastle. She was sent to prison for 30 days. "Mrs. Brailsford, who had struck at the barricade with an axe, was also given the option of being bound over, which she, of course, refused, with the alternative of a month's imprisonment in the second division. We were put again into a van, but had only a short way to drive. We were shown into a passage of the prison where the Governor came and spoke to us. He was very civil, and begged us not to go on the hunger-strike." She did but as she pointed out in Prisons and Prisoners (1914) after a couple of days "the wardress came in and announced that I was released, because of the state of my heart!"

Mary Leigh and Emily Wilding Davison were caught throwing stones at a car taking David Lloyd George to a meeting in Newcastle. The stones were wrapped in Emily's favourite words: "Rebellion against tyrants is obedience to God." The women were found guilty and sentenced to one month's hard labour at Strangeways Prison. The women went on hunger strike but once again the prison authorities decided to force-feed the women. The WSPU initiated legal proceedings against the home secretary, prison governor, and prison doctor on Mary Leigh's behalf, opening a defence fund in her name. The case was brought to trial in December 1909, and the jury found for the defence, upholding the defence's claim that forcible feeding had been necessary to preserve life and that minimum force had been used.

Herbert Gladstone, who was in fact a supporter of votes for women, refused to back-down over forced-feeding. "My duty is unpleasant and distasteful enough, but that is no reason why I should shirk it. I admire the gallantry of many of these girls as strongly as I detest the unscrupulous use use which is being made of their qualities by older women who should know better. Women's franchise will come, but it will come not through violent actions and not through sentimental or cowardly surrender to them."

Christabel Pankhurst made it clear that the WSPU would not change their tactics and members in prison would continue to go on hunger-strike. "They (members of the Liberal government) shall not have peace. We have at last got up steam and tasted the joy of battle. Our blood is up... the more they ask for quarter the less they shall get. We will not betray the women in prison... For the weak to use their little strength against the huge forces of tyranny is divine." However, Christabel made sure she was not arrested during this period as she did not want to "undergo forcible feeding" and "intended to postpone this distasteful eventually for as long as possible".

Emmeline Pankhurst's sister, Mary Clarke, was the organiser of the WSPU in Brighton. According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "Facing the rude violence of the seaside rowdies at Brighton, where she was stationed, she displayed a quiet, persistent courage, which made peculiarly large demands on one so sensitive. Exerting her frail physique to its utmost, she was grievously ill on the eve of Black Friday, and her Brighton comrades had begged her not to go. She had promised to take the easier course of arrest for window-breaking, and had telegraphed to Brighton from the police court."

Clarke was arrested and sent to Holloway Prison, where she endured a hunger-strike and forced-feeding. She was released on 22nd December, 1910 but two days later Emmeline Pankhurst found her unconcious and she died soon afterwards as a result of a burst blood vessel on the brain. It has been claimed that Clarke was the first of several suffragettes, probably died as a result of being forced fed in prison.

Emmeline Pankhurst wrote to C. P. Scott: "We who love her and know the beauty of her selfless life, feel it hard to restrain our human desire for vengeance although we know had she foreseen the consequence of her imprisonment she would have been proud and glad to die for the cause of freedom. She is the first to die. How many must follow before the men of your party realize their responsibility."

In early 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence both disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU.

Christabel Pankhurst later recorded: "Mother and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence went on hunger-strike. The Government retaliated by forcible feeding. This was actually carried out in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. The doctors and wardresses came to Mother's cell armed with forcible-feeding apparatus. Forewarned by the cries of Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence… Mother received them with all her majestic indignation. They fell back and left her. Neither then nor at any time in her log and dreadful conflict with the government was she forcibly fed."

Frederick Pethhick Lawrence was made to suffer force-feeding twice a day for ten days before his release: "The head doctor, a most sensitive man, was visibly distressed by what he had to do. It certainly was an unpleasant and painful process and a sufficient number of warders had to be called in to prevent my moving while a rubber tube was pushed up my nostril and down into my throat and liquid was poured through it into my stomach. Twice a day thereafter one of the doctors fed me in this way. I was not allowed to leave my cell in the hospital and for the most part I had to stay in bed. There was nothing to do but to read; and the days were very long and went very slowly."

Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses".

The women responsible for these arson attacks were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Determined to avoid these women becoming martyrs, the government introduced the Prisoner's Temporary Discharge of Ill Health Act. Suffragettes were now allowed to go on hunger strike but as soon as they became ill they were released. Once the women had recovered, the police re-arrested them and returned them to prison where they completed their sentences. This successful means of dealing with hunger strikes became known as the Cat and Mouse Act.

On 24th February 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested for procuring and inciting persons to commit offences contrary to the Malicious Injuries to Property Act 1861. The Times reported: "Mrs Pankhurst, who conducted her own defence, was found guilty, with a strong recommendation to mercy, and Mr Justice Lush sentenced her to three years' penal servitude. She had previously declared her intention to resist strenuously the prison treatment until she was released. A scene of uproar followed the passing of the sentence."

Dr. Charles Mansell-Moullin joined forces with Sir Victor Horsley and Dr. Agnes Savill to write a report on the impact of the forced-feeding of suffragettes. In a speech on 13th March, 1913 he argued that Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, had been making misleading statements to the House of Commons: "Now Mr. McKenna has said time after time that forcible feeding, as carried out in His Majesty's prisons, is neither dangerous nor painful. Only the other day he said, in answer to an obviously inspired question as to the possibility of a lady suffering injury from the treatment she received in prison, "I must wait until a case arises in which any person has suffered any injury from her treatment in prison."... He relies entirely upon reports that are made to him - reports that must come from the prison officials, and go through the Home Office to him, and his statements are entirely founded upon those reports. I have no hesitation in saying that these reports, if they justify the statements that Mr. McKenna has made, are absolutely untrue. They not only deceive the public, but from the persistence with which they are got up in the same sense, they must be intended to deceive the public."

After going nine days without eating, they released Emmeline Pankhurst for fifteen days so she could recover her health. "They sent me away, sitting bolt upright in a cab, unmindful of the fact that I was in a dangerous condition of weakness, having lost two stone in weight and suffered seriously from irregularities of heart action." On 26th May, 1913, when Emmeline Pankhurst attempted to attend a meeting, she was arrested and returned to prison.

During this period Kitty Marion was the leading figure in the WSPU arson campaign and she was responsible for setting fire to Levetleigh House at St Leonards (April 1913), the Grandstand at Hurst Park racecourse (June 1913) and various houses in Liverpool (August, 1913) and Manchester (November, 1913). These incidents resulted in a series of further terms of imprisonment during which force-feeding occurred followed by release under the Cat & Mouse Act. It has been calculated that Marion endured 200 force-feedings in prison while on hunger strike.

A number of significant figures in the WSPU left the organisation over the arson campaign. This included Elizabeth Robins, Jane Brailsford, Laura Ainsworth, Eveline Haverfield, Mary Blathwayt and Louisa Garrett Anderson. Leaders of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage such as Henry N. Brailsford, Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman, argued "that militancy had been taken to foolish extremes and was now damaging the cause".

Hertha Ayrton, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Janie Allan and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson stopped providing much needed funds for the organization. Colonel Linley Blathwayt and Emily Blathwayt also cut off funds to the WSPU. In June 1913 a house had been burned down close to Eagle House. Under pressure from her parents, Mary Blathwayt resigned from the WSPU.

Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst were both expelled from the WSPU by Christabel Pankhurst in February 1914, for refusing to follow orders. Beatrice Harraden, a member of the WSPU since 1905, wrote a letter to Christabel calling on her to bring an end to the arson campaign and accusing her of alienating too many old colleagues by her dictatorial behaviour: "It must be that... your exile (in Paris) prevents you from being in real touch with facts as they are over here."

Henry Harben complained that her autocratic behaviour had destroyed the WSPU: "People are saying that from the leader of a great movement you are developing into the ringleader of a little rebel Rump." According to Martin Pugh "she had fallen into the error of all autocratic leaders; her power to manippulate personnel was so complete that it left her increasingly surrounded by sycophants who lacked real ability."

On this day in 1912 Margaret Macfarlane publishes her account of being forced-fed in Votes for Women. .

On Wednesday at 2 pm we were forceibly fed - all of us. I was fed three times. The first time was at 2 pm on Wednesday afternoon. When the doctor came to pay an official visit afterwards. I made a strong complaint to him on the way I have been treated. I asked him if he thought I was going to gain by those two thimblefuls of greul that I had taken after having a quarter of an hour's horseplay from four wardresses?

People imagine that there is a nurse sitting kindly by the bedside stroking the prisoner's forehead, and the prisoner is sipping from the feeding-cup. Instead of that, I was lifted into a chair and tied with a strong sheet to the back of the chair. As far as I can remember, my arms were held on each side on the arms of the chair. There was a wardress with a feeding cup (this wardress was 5 ft. 10½ in height, and very strong) and one behind my chair, making a gag for the mouth with her fingers. Another held my knees. I told them that I would not swallow a drop of the gruel voluntarily. When they found that I did not retain any of the food, the one who was gagging me egged the others on to tickle me, to hold my nose to make me swallow, and to grip me on the throat, which to me is the most cruel. The pressing of the throat to make one swallow gives a fearful feeling of suffocation. When they got my feet up, my head was hanging right over the back of the chair, which added to the choking sensation.

On this day in 1948 National Health Service Act is passed by Parliament. The right-wing national press was opposed to the idea of a National Health Service. The Daily Sketch reported: "The State medical service is part of the Socialist plot to convert Great Britain into a National Socialist economy. The doctors' stand is the first effective revolt of the professional classes against Socialist tyranny. There is nothing that Bevan or any other Socialist can do about it in the shape of Hitlerian coercion."

Winston Churchill led the attack on Aneurin Bevan. In one debate in the House of Commons he argued that unless Bevan "changes his policy and methods and moves without the slightest delay, he will be as great a curse to his country in time of peace as he was a squalid nuisance in time of war." The Conservative Party voted against the measure. The Tory ammendment stated that it "declines to give a Third Reading to a Bill which discourages voluntary effort and association; mutilates the structure of local government; dangerously increases minisaterial power and patronage; approppriates trust funds and benefactions in contempt of the wishes of donors and subscribers; and undermines the freedom and independence of the medical profession to the detriment of the nation." However, on 2th July, 1946, the Third Reading was carried by 261 votes to 113. Michael Foot commented that the Conservatives had voted against the "most exciting and popular of the Government's measures a bare four months before it was to be introduced".

David Widgery, the author of The National Health: A Radical Perspective (1988) admitted that "the Act was bold in outline; a National Health Service entirely free at the time of use, financed out of general taxation and able to organise preventive medicine, research and paramedical aids on a national basis... Bevan himself was apparently well prepared to deal with conservative pressures, and he was quite prepared for the out-break of near-hysteria by doctors, skilfully orchestrated by Charles Hill of the BMA, who had endeared himself to the listening public during the war as the smooth-spoken, concerned Radio Doctor."

Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA), led by Charles Hill, mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. One doctor was cheered at a BMA meeting for saying that the proposed NHS bill was "strongly suggestive" of what had been going in Nazi Germany.

By July 1948, Aneurin Bevan had guided the National Health Service Act safely through Parliament. The Government resolution was carried by 337 votes to 178. Niall Dickson has pointed out: "The UK's National Health Service (NHS) came into operation at midnight on the fourth of July 1948. It was the first time anywhere in the world that completely free healthcare was made available on the basis of citizenship rather than the payment of fees or insurance premiums... Life in Britain in the 30s and 40s was tough. Every year, thousands died of infectious diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio. Infant mortality - deaths of children before their first birthday - was around one in 20, and there was little the piecemeal healthcare system of the day could do to improve matters. Against such a background, it is difficult to overstate the impact of the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS). Although medical science was still at a basic stage, the NHS for the first time provided decent healthcare for all - and, at a stroke, transformed the lives of millions."

The Manchester Guardian commented on the passing of the National Health Service Act: "These two reforms have sometimes been greeted as a large installment of Socialism in this country. They are not strictly that, for many besides Socialists have contributed something to them. What they mark is rather an advance of the equalitarianism which has been the mainspring, though not the exclusive possession, of the British Labour movement. They are designed to offset as far as they can the inequalities that arise from the chances of life, to ensure that a "bad start" or a stroke of bad luck, illness or accident or loss of work, does not carry the heavy, often crippling, economic penalty it has carried in the past. It is important to realise the fundamental change in attitude which this implies, and its consequences for our social evolution."

In October 1950, Clement Attlee promoted Hugh Gaitskell to chancellor of the exchequer. Aneurin Bevan considered Gaitskell as hostile to the National Health Service and sent a letter to Attlee commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement."

One of Gaitskell's first tasks was to balance the budget. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973) has argued: "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year-by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon."