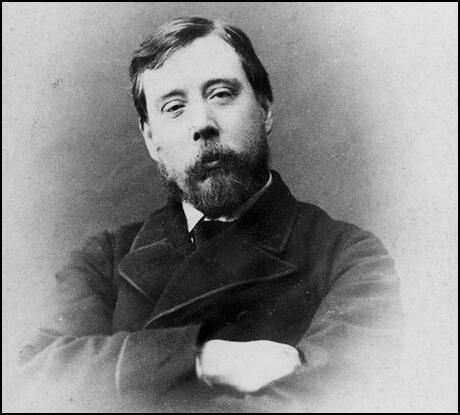

Richard Pankhurst

Richard Pankhurst, the son of an auctioneer, was born in Stoke in May 1834. Richard's father had originally been a member of the Church of England and the Conservative Party, but eventually become a Baptist and supporter of the Liberal Party. As a youth Richard taught at Baptist Sunday School in Manchester but later he became an agnostic.

Pankhurst was educated at Manchester Grammar School and the University of London. He graduated in 1858 and after a period at Lincoln's Inn qualified as a barrister. Pankhurst joined the Liberal Party and was active in the campaign for social reform. A supporter of free secular education for all, he started evening classes for working class people at Owens College in Manchester.

As a barrister, Pankhurst took a strong interest in legal reform. He was especially interested in changing those laws that discriminated against women. Pankhurst was legal adviser to Lydia Becker and the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage. In 1869 he drafted the amendment which included women in the Municipal Corporation Bill. The following year he was responsible for drafting the first bill for the enfranchisement of women ever presented to Parliament. Pankhurst also wrote the Married Women's Property Act of 1870, although it was much altered after it went through Parliament.

In 1879 Pankhurst married Emmeline Goulden. The couple had five children, including Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst, who were later to play a prominent role in the WSPU. Pankhurst remained involved in the struggle for women's rights and in 1882 drafted the Married Women's Property Act.

Pankhurst continued to be active in the Liberal Party until 1883 when he resigned over policy issues. Later that year he was an Independent candidate for a by-election in Manchester. Pankhurst's campaigned on a radical programme that included universal adult suffrage, payment of salaries for MPs, Disestablishment of the Church of England, free compulsory elementary education, Irish Home Rule, land nationalization and the abolition of the House of Lords. He was defeated in the election by 18,188 to 6,216.

In 1885 the Pankhurst family moved to London. He became friends with leading radicals in the capital including William Morris, Tom Mann, Eleanor Marx and Annie Besant. In 1885 he spoke on the same platform as Helen Taylor. His daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst, later revealed that her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, was disturbed by the fact that she wore trousers during the meeting: "Mrs Pankhurst was distressed that her husband should be seen walking with the lady in this garb, and feared that his gallantry in doing so... would cost him many votes."

Pankhurst joined the Fabian Society and played a leading role in the protest against police behaviour during the events of Bloody Sunday in 1887. During these years Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst continued their involvement in the struggle for women's rights and in 1889 helped form the pressure group, the Women's Franchise League. The organisation's main objective was to secure the vote for women in local elections.

In 1893 Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst returned to Manchester where they formed a branch of the new Independent Labour Party (ILP). In the 1895 General Election, Pankhurst stood as the ILP candidate for Gorton, an industrial suburb of the city, but was defeated.

For several years Richard Pankhurst suffered from gastric ulcers. Towards the end of 1897 they became more severe and he died on 5th July, 1898. "Faithful and True My Loving Comrade", a quote from Walt Whitman, were the words Emmeline choose for his gravestone.

Primary Sources

(1) Emmeline Pankhurst, My Own Story (1914)

I came to know Dr. Richard Pankhurst, a lawyer… who was a supporter of woman's suffrage… Dr. Pankhurst acted as counsel for the Manchester women who tried in 1868 to be placed on the register as voters. He also drafted the bill giving married women absolute control over their property and earnings, a bill, which became law in 1882.

I think we cannot be too grateful to the group of men and women, who, like Dr. Pankhurst, lent the weight of their honoured names to the suffrage movement in the trials of its struggling youth. These men did not wait until the movement became popular, nor did they hesitate until it was plain that women were roused to the point of revolt. They worked all their lives with those who were organising, educating and preparing for the revolt which was one day to come. Unquestionably those pioneer men suffered in popularity for their feminist views.

(2) Christabel Pankhurst, Unshackled (1959)

The picture now in my mind of those Manchester days is of the library, with flowered gold-and-brown paper and book-lined walls. Mother reading, writing or sewing on one side of the big, glowing fire. Father at the other side, deep in a book. He stretches out his fine sensitive hand, now and again, to show that he is thinking of us all and enjoying our companionship. We schoolchildren had leave to do our homework at the big table and suddenly one or another would ask: 'Father, what is such and such?' or 'Who was so and so?' He was roused at once. Books were taken from the shelves, references and authorities were shown. The subjected was illuminated in all its ramifications.

(3) As a young girl Sylvia Pankhurst went with her father Richard Pankhurst, when he was campaigning for the Independent Labour Party in Manchester.

Often I went on Sunday mornings with my father to the dingy streets of Ancoats, Gorton, Hulme, and other working-class districts. Standing on a chair or soap-box, pleading the cause of the people with passionate earnestness, he stirred me, as perhaps he stirred no other auditor, though I saw tears in the faces of the people about him. Those endless rows of smoke-begrimed little houses, with never a tree or a flower in sight, how bitterly their ugliness smote me! Many a time in spring, as I gazed upon them, those two red may trees in our garden at home would rise up in my mind, almost menacing in their beauty; and I would ask myself whether it could be just that I should live in Victoria Park, and go well fed and warmly clad, whilst the children of these grey slums were lacking the very necessities of life. The misery of the poor, as I heard my father plead for it, and saw it revealed in the pinched faces of his audiences, awoke in me a maddening sense of impotence; and there were moments when I had an impulse to dash my head against the dreary walls of those squalid streets.