On this day on 1st February

On this day in 1840 Lord Melbourne, announces that instead of the men involved in the Newport Rising being executed they would be transported for life.

In May 1838 Henry Vincent was arrested for making inflammatory speeches. When he was tried on the 2nd August at Monmouth Assizes he was found guilty and sentenced to twelve months imprisonment. Vincent was denied writing materials and only allowed to read books on religion.

Chartists in Wales were furious and the decision was followed by several outbreaks of violence. John Frost toured Wales making speeches urging people not to break the law. Instead Frost called for a massive protest meeting to show the strength of feeling against the imprisonment of Henry Vincent. Frost's plan was to march on Newport where the Chartists planned to demand the release of Vincent.

The authorities in Newport heard rumours that the Chartists were armed and planned to seize Newport. Stories also began to circulate that if the Chartists were successful in Newport, it would encourage others all over Britain to follow their example.

When John Frost and the 3,000 marchers arrived in Newport on 4th November 1839 they discovered that the authorities had made more arrests and were holding several Chartists in the Westgate Hotel. The Chartists marched to the hotel and began chanting "surrender our prisoners". Twenty-eight soldiers had been placed inside the Westgate Hotel and when the order was given they began firing into the crowd. Afterwards it was estimated that over twenty men were killed and another fifty were wounded.

Frost and others involved in the march on Newport were arrested and charged with high treason. Several of the men, including John Frost, were found guilty and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. The severity of the sentences shocked many people and protests meetings took place all over Britain. Some Physical Force Chartists called for a military uprising but Feargus O'Connor refused to lead an insurrection.

The British Cabinet discussed the sentences and on 1st February the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, announced that instead of the men being executed they would be transported for life. John Frost was sent to Tasmania where he worked for three years as a clerk and eight years as a school teacher.

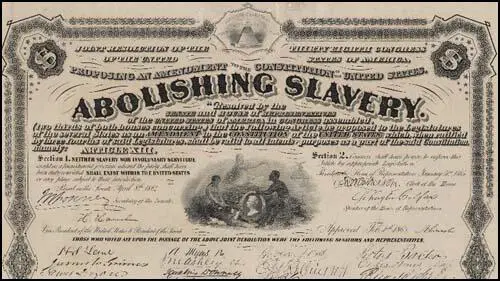

On this day in 1865 President Abraham Lincoln signs the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. On 23rd September, 1862 President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation. The statement said that all slaves would be declared free in those states still in rebellion against the United States on 1st January, 1863. The measure only applied to those states which, after that date, came under the military control of the Union Army. It did not apply to those slave states such as Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri and parts of Virginia and Louisiana, that were already occupied by Northern troops.

The Thirteenth Amendment was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18.

On this day in 1879 Mary Blathwayt, the daughter of Colonel Linley Blathwayt, a retired army officer, and Emily Blathwayt, was born in 1879. Her father was an officer in the British Indian Army and served in India for many years. Blathwayt retired from the army and in 1882 he purchased Eagle House near Batheaston, a large house set in four acres of land.

Linley Blathwayt was a supporter of the Liberal Party. Mary and her mother also held progressive political views and were both advocates of women's suffrage. Mary and her mother devoted much of their time to teaching music to village children.

According to B. M. Willmott Dobbie, the author of A Nest of Suffragettes in Somerset (1979): "Mary led the sheltered life of an upper middle-class daughter at home, paying and receiving calls, helping with charitable events in the village, working in the garden and tending her hens, for whom she had an especial fondness, taking an active part in the Avon Vale Musical Society, giving violin lessons to village boys, who invariably disappointed her.... There were cycle rides with girl friends, and tours with her brother William, whom they always stayed in Temperance Hotels."

In July 1906 she sent a donation of 3 shillings to Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Her mother and father also supported the Women's Suffrage bill being discussed in the House of Commons. In March 1907 Emily Blathwayt wrote: "Women's Suffrage bill brought in by private member and government allowed it to be talked out. The Liberals do not keep their pledges. The Women's Union beg all to turn against Liberals and think only of the one Cause. Linley is much in favour of women having the vote, he thinks they would do much more good than harm."

Mary became friends with Lilias Ashworth Hallett, who was a member of the NUWSS and the WSPU. In March 1908 she was introduced to Millicent Fawcett. In her diary she wrote: "This afternoon I went into Bath by tram and then walked to Claverton Lodge... Mrs. Ashworth Hallett introduced me first to Miss Clark, and then to Mrs. Fawcett. Then others came in: Dr. Mary Morris... We all had tea there and stayed talking till 6.30. I have never been to the house before; it is a beautiful place. Mrs. Hallett is most kind. I could not believe I was looking at Mrs. Fawcett, she looks so young. I believe she has been working for Votes for Women for 40 years."

Mary Blathwayt first met Annie Kenney at a WSPU meeting in Bath. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), claims that Blathwayt had fallen "under her spell and gave her a rose". Soon afterwards Kenney introduced her to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Christabel Pankhurst. She now became an active member and over the next few weeks she began distributing WSPU leaflets in the area.

In May 1908 Mary agreed to help Annie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Clara Codd and Mary Phillips to organise the women's suffrage campaign in her area. She wrote in her diary: "This afternoon I helped Annie Kenney make her plans for a West of England campaign, I wrote out lists of towns and dates which are to be sent to Mrs. Pankhurst and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence. This evening Miss Howey went round the town with some steps, and I went with her. And when we came to a crowd she got onto the steps and shouted Keep the Liberal out. Votes for Women". Mary also a public meeting that was addressed by Gladice Keevil. She recorded in her diary: "She and I held an open air meeting at the Wharf. I took the chair, the first time I have ever done such a thing. I read out a few words of introduction, announced a meeting for tomorrow and called upon Miss Keevil to speak."

By December of that year Mary Blathwayt was elected to the executive committee of the local branch of the WSPU. Blathwayt became very friendly with Annie Kenney. The two women spent much of 1908 and 1909 speaking "from dogcarts at open-air meetings, chalked pavements and sold pamphlets." However, she refused to become involved in any activity that might risk her being arrested. In July 1909 she refused a written request from Emmeline Pankhurst to join a deputation "which carried with it the virtual certainty of a prison sentence." The reason that she gave was that "father would not like it". She also noted in her diary that "Annie Kenney does not wish me to go."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote an article in Votes for Women in February 1909, they acknowledged the help given by the Blathwayt family to the cause of women's suffrage: "I say to you young women who have private means or whose parents are able and willing to support you while they give you freedom to choose your vocation. Come and give one year of your life to bringing the message of deliverance to thousands of your sisters... Put yourself through a short course of training under one of our chief officers or at headquarters in London, and then become one of our honorary staff organisers. Miss Annie Kenney, in the West of England, has two such honorary organisers. Miss Blathwayt is the only daughter of Colonel Lindley Blathwayt, of Bath. Yet her parents have set her free with their fullest approbation and sympathy, and with a generous allowance, to devote her whole time to the work."

On 8th June, 1909, Mary recorded in her diary how she and Elsie Howey were attacked during one public meeting in Bristol. "We were on a lorry and a large crowd of children were waiting for us when we arrived. Things were thrown at us all the time; but when we drove away at the end we were hit a great many times. Elsie Howey had her lip hit and it bled. I was hit by potatoes, stones, turf and dust. Something hit me very hard on my right ear as I was getting into our tram. Someone threw a big stone as big as a baby's head; it fell onto the lorry."

Elizabeth Crawford claims Annie Kenney spent a lot of time at Mary Blathwayt's home, Eagle House near Batheaston "where, for the first time, she began to learn French, to play tennis, to swim, to ride and to drive." A fellow member of the WSPU, Teresa Billington-Greig claimed that Kenney was "emotionally possessed" by Christabel Pankhurst during this period. However, Mary argued that it was Kenney who was the dominating personality as she had a "wonderful influence over people".

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that Annie Kenney had a series of romantic attachments with other suffragettes: "The relationship (with Christabel Pankhurst) would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments. One historian who argues that Annie must have had sexual feelings for other women adds that lesbianism was barely recognised at the time. Such relationships, even when they involved sharing beds, excited little comment. Already, Christabel had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family - according to Sylvia."

Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of the estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest". Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay at Eagle House and the summer-house. Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU at Batheaston. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote on 7th September 1910 that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account.

The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else."

Colonel Linley Blathwayt decided to create a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. The idea was for women to be invited to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes. On 23rd April 1909 Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Constance Lytton and Clara Codd all planted trees. "Beautiful day for the tree planting and Linley photographed the three in a group at each tree. Annie put the West one, Mrs. P. Lawrence, South, and Lady Constance the East. Miss Codd came to the field."

Over the next few months Emmeline Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Mary Phillips, Vera Holme, Jessie Kenney, Georgina Brackenbury, Marie Brackenbury, Aeta Lamb, Theresa Garnett, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Adela Pankhurst, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Vera Wentworth and Elsie Howey also took part in this ceremony. After the visit of Christabel Pankhurst Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "Christabel has planted her cedar of Lebanon by the pond; it was raining all the time. There is a wonderful charm about Christabel; she looks sweet and not like her photo. She is quiet and retiring." Eventually, even women who had not been to prison, such as Millicent Fawcett and Lilias Ashworth Hallett planted trees.

Jessie Kenney developed a "lung condition" also spent time recovering at Eagle House in 1910. Others who visited during this period included Constance Lytton, Elsie Howey, Mary Phillips, Charlotte Despard, Mary Allen, Charlotte Marsh, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Aeta Lamb, Georgina Brackenbury, Marie Brackenbury, Marie Naylor, Laura Ainsworth, Margaret Haig Thomas, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Theresa Garnett, Gladice Keevil, Maud Joachim, Vida Goldstein, Minnie Baldock, Vera Wentworth, Clare Mordan and Helen Watts. Colonel Blathwayt photographed the women. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars.

In April 1911 Mary Blathwayt took part in the campaign to undermine the national census. She wrote in her diary: "I went into Bath last night by tram and walked to 12 Lansdown Crescent (an empty house rented for the purpose by Mrs. Mansel) to spend the night there and so evade the census, as a protest against the Government for not giving us Votes for Women. I got there before 10 o'clock. A little crowd of people were standing in the next doorway on the east side to watch us go in. I took a nightdress etc. with me and had a room to myself on the 1st floor and a bed. Everyone else slept on mattresses. We had a charming room to hold our meeting, beautifully decorated and very comfortable. There were 29 of us... We sat up until 2 a.m. this morning."

Annie Kenney wrote in her memoirs, Memories of a Militant (1924) about the help that the Blathwayt family gave her during the campaign: "It would be futile to mention other names, they were all wonderful to me. There is just one I should like to mention, that of the late Colonel Blathwayt. He and Mrs. Blathwayt, of Eagle House, Batheaston treated me as though I were one of their own family. All my week-ends I spent under their hospitable roof."

In November 1912 Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary that she was unhappy about her daughter's participation in the WSPU. "Mary in Bath all day working for the Pankhurst cause - we wish she was not, but the young people all do this kind of thing now and I suppose it is evolution. The oldest supporters are fast leaving the WSPU, especially those old in years, but people like Miss Lamb do not at all like Mrs. Pankhurst's present policy."

The summer of 1913 saw a further escalation of WSPU violence when they began an arson campaign. In July attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. This was followed by cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire. In June 1913 a house had been burned down close to Eagle House. Under pressure from her parents, Mary Blathwayt resigned from the WSPU.

In her diary she wrote: "I have written to Grace Tollemache (secretary for Bath) and to the secretary of the Women's Social and Political Union to say that I want to give up being a member of the W.S.P.U. and not giving any reason. Her mother, Emily Blathwayt, wrote in her diary: "I am glad to say Mary is writing to resign membership with the W.S.P.U. Now they have begun burning houses in the neighbourhood I feel more than ever ashamed to be connected with them."

Emily and Mary remained active member of the NUWSS. Emily wrote in her diary on 7th February, 1918: "The Reform Bill passed yesterday... Women cannot vote before the age of 30. Wives of men entitled to elect can vote as well as women in their own right and university women also have the franchise... Linley and I walked through the trees this afternoon and wondered how quietly this had come at last, but the war occupies all our thoughts."

Mary Blathwayt continued to live in Batheaston until her death in 1962. Eagle House was sold soon afterwards. B. M. Willmott Dobbie, the author of A Nest of Suffragettes in Somerset (1979), has pointed out: "The land was sold for building. Bulldozers tore down the suffragette trees, and blithely smashed many of the plaques. A number were rescued, however, and are in the museum of the Batheaston Society."

On this day in 1902, Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, on 1st February, 1902. His father deserted the family and Hughes was mainly brought up by his grandmother, whose husband had been killed during the insurrection at Harper's Ferry. His grandmother taught him about Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth and at an early age he was introduced to the writings of William Du Bois. Hughes was also taken to hear Booker T. Washington speak at a public meeting.

Hughes became interested in poetry and was especially influenced by the work of Carl Sandburg and Walt Whitman. In 1921 his poem, Speaks of Rivers, was published in Crisis, the journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

He attended Columbia University (1921-22) before working as a steward on a ship bound for Africa. Later he travelled through Italy, Holland, Spain and France before returning to New York City where he published two volumes of poetry, The Weary Blues (1926) and Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927). He also had a essay, The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain, published in The Nation. The work was well-received and helped him win a scholarship to Lincoln University, Pennsylvania.

Hughes published a novel, Not Without Laughter (1930), a collection of short-stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934) and a play, The Mulatto (1935). Much of his work dealt with the effects of the Depression on the American people. Hughes also wrote for the Marxist journal, the New Masses and in 1937 reported on the Spanish Civil War.

Hughes visited the Soviet Union and on his return published A Negro Looks at Soviet Central Asia (1934), where he praised the country's treatment of racial minorities. He had several friends in the American Communist Party but this came to an end with the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

In 1948 he publicly endorsed Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace for president and the following year he condemned the prosecution of Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green under the Alien Registration Act.

A victim of McCarthyism, in March, 1953 Hughes was forced to appear before the House of Un-American Activities. Hughes refused to name the names of other radicals and denied he had ever been a member of the American Communist Party. However, in the months following the hearings, William Du Bois criticised Hughes for failing to defend the victimization of Paul Robeson. Later, he declared his radicalism an error of his youth.

Hughes published several volumes of poetry including: Shakespeare in Harlem (1942), Fields of Wonder (1947), Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951) and Ask Your Mama (1961). He also published two autobiographies: The Big Sea (1940) and I Wonder as I Wander (1956). Langston Hughes died on 22nd May, 1967.

On this day in 1915 Stanley Matthews, the son of a barber and professional boxer, Jack Matthews, was born in Hanley. Jack Matthews took out his son training from an early age. His initial intention was for Stanley to become a boxer. However, Stanley had no interest in this sport. As he pointed out in his autobiography: "I had only one thing on my mind - to be a footballer."

Jack Matthews told his son that he could become a professional footballer "If you can make yourself good enough to be a schoolboy international before you leave school". Matthews achieved this when he played for England schoolboys against Wales when he was only 13 years old. England won the game 4-1.

In 1932 he signed for local club, Stoke City in the Second Division. The club got promoted to the First Division in the 1932-33 season. Matthews, who was only 18 years old at the time, won his first international cap for England against Wales on 29th September, 1934. The England team that day also included Eddie Hapgood, Ray Westwood, Cliff Britton and Eric Brook. Matthews scored one of the goals in England's 4-0 victory. He retained his place in the game against Italy on 14th November, 1934. A game that England won 3-2.

Stoke City struggled in the First Division and for a time he lost his place in the England side. On 17th April, 1937, he won his fourth international cap against Scotland. His wing partner that day was Raich Carter. However, the two men did not play well together and as a result Carter was dropped from the side. Tommy Lawton found the dropping of Carter inexplicable. "Raich was the perfect team man. He would send through pinpoint passes or be there for the nod down."

Raich Carter later explained why he never played well with Matthews: "He was so much of the star individualist that, though he was one of the best players of all time, he was not really a good footballer. When Stan gets the ball on the wing you don't know when it's coming back. He's an extraordinary difficult winger to play alongside."

One national newspaper even claimed that the other players in the team were so upset with Matthews that they refused to pass to him. Tommy Lawton admitted that: "We all had moments when we've been exasperated with Stan because he'd taken the ball off down the wing as if he was playing on his own." However, he rejected the idea that the players starved him of the ball because eventually "he'd produce a moment of sheer genius that nobody else could hope to match."

On 1st December, 1937, Matthews scored a hat-trick in England's 5-4 victory over Czechoslovakia. The England team that day also included Vic Woodley, Wilf Copping, Stan Cullis, Len Goulden, Willie Hall, John Morton and Bert Sproston.

In the 1937-38 season Stoke City finished in 17th place in the First Division of the Football League. Matthews was desperate to win league or cup medals and asked for a transfer. More than 3,000 fans attended a protest meeting and a further 1,000 marched outside the ground with placards. Matthews eventually agreed to stay.

In May 1938 Matthews was selected for the England tour of Europe. The first match was against Germany in Berlin. Adolf Hitler wanted to make use of this game as propaganda for his Nazi government. While the England players were getting changed an Football Association official went into their dressing-room and told them that they had to give the raised arm Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem. As Matthews later recalled: "The dressing room erupted. There was bedlam. All the England players were livid and totally opposed to this, myself included. Everyone was shouting at once. Eddie Hapgood, normally a respectful and devoted captain, wagged his finger at the official and told him what he could do with the Nazi salute, which involved putting it where the sun doesn't shine."

The FA official left only to return some minutes later saying he had a direct order from Sir Neville Henderson the British Ambassador in Berlin. The players were told that the political situation between Britain and Germany was now so sensitive that it needed "only a spark to set Europe alight". As a result the England team reluctantly agreed to give the Nazi salute.

The game was watched by 110,000 people as well as senior government figures such as Herman Goering and Joseph Goebbels. England won the game 6-3. This included a goal scored by Len Goulden that Matthews described as "the greatest goal I ever saw in football". According to Matthews: "Len met the ball on the run; without surrendering any pace, his left leg cocked back like the trigger of a gun, snapped forward and he met the ball full face on the volley. To use modern parlance, his shot was like an Exocet missile. The German goalkeeper may well have seen it coming, but he could do absolutely nothing about it. From 25 yards the ball screamed into the roof of the net with such power that the netting was ripped from two of the pegs by which it was tied to the crossbar."

On Friday, 1st September, 1939, Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. On Sunday 3rd September Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany. The government immediately imposed a ban on the assembly of crowds and as a result the Football League competition was brought to an end.

On 14th September, the government gave permission for football clubs to play friendly matches. In the interests of public safety, the number of spectators allowed to see these games was limited to 8,000. These arrangements were later revised, and clubs were allowed gates of 15,000 from tickets purchased on the day of the game through the turnstiles. The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place.

During the Second World War Matthews served in the Royal Air Force. Like most top footballers, Matthews was stationed in England and was allowed to play in friendly games. This included guesting for Blackpool, Manchester United and Arsenal.

Neil Franklin was made captain of Stoke City in the 1946-47 season. Stories circulated that Matthews was dropped from the team by Bob McGrory and replaced by George Mountford because he was "unpopular" in the dressing-room. As his friend, Tom Finney, later explained: "Neil called a meeting of the players, sought their collective view, informed Stanley by letter of his intentions and strode off to see the board to quash the rumours and pay handsome tribute to his illustrious team-mate." Matthews later wrote: "The problem was not resolved, but knowing that I had the support of my team-mates, including George Mountford who had replaced me, made me feel a whole lot better about the whole sorry affair."

Stanley Matthews now lost his place in the England team. He now decided he must play for a club that had the possibility of winning the FA Cup or the league championship. On 10th May, 1947, Matthews was transferred to Blackpool for £11,500. This was a large sum of money to pay for someone aged 32 and considered past his best. However, Blackpool manager, Joe Smith, was extremely pleased with his signing. He joined a team that included Hughie Kelly, Stan Mortensen, Harry Johnson and Bill Perry.

In the 1947-48 season Blackpool beat Chester (4-0), Colchester United (5-0), Fulham (2-0), Tottenham Hotspur (3-1) to reach the final of the FA Cup. However, Blackpool lost the game 4-2 to Manchester United. Matthews played well that season and the Football Writers' Association (FWA) awarded him the first Footballer of the Year Award.

Matthews also regained his place in the England team and was a member of the team that had victories against Scotland (2-0), Italy (4-0), Northern Ireland (6-2), Wales (1-0) and Switzerland (6-0).

In the 1950-51 season Blackpool finished in 3rd place in the First Division of the Football League. Blackpool beat Stockport County (2-1), Mansfield Town (2-0), Fulham (1-0) and Birmingham City (2-1) to reach the final of the FA Cup. Once again Matthews only received a losing medal as Newcastle United won the game 2-0.

Stanley Matthews described Ernie Taylor as the "architect of our cup final defeat" urged the club manager, Joe Smith, to buy the man who was nicknamed "Tom Thumb". Matthews later recalled: "Ernie was a cheeky, confident player who on his day verged on the brilliant. Despite his slight build, he could ride even the most brusque of tackles with aplomb and he could crack open even the most challenging and organised of defences." Smith took the advice and in October 1951, paid £25,000 for Taylor.

In the 1952-53 season beat Huddersfield Town (1-0), Southampton (2-1), Arsenal (2-1) and Tottenham Hotspur (2-1) to reach the FA Cup final for the third time in five years. Cyril Robinson claimed that Joe Smith, the Blackpool manager "was never very tactical, he was very blunt with his instructions". According to Stanley Matthews he said: "Go out and enjoy yourselves. Be the players I know you are and we'll be all right."

Cyril Robinson was later interviewed about the match: "We kicked off and within a couple of minutes we had a goal scored against us. That's about the worst thing that could happen. Gradually we got some passes together, got Stan Matthews on the ball and Mortensen got the equaliser, but they went back ahead straight away."

Stanley Matthews wrote in his autobiography that: "At half-time we sipped our tea and listened to Joe. He wasn't panicking. He didn't rant and rave and he didn't berate anyone. He simply told us to keep playing our normal game." Harry Johnson, the captain, told the defence to "be more compact and tighter as a unit." He also added: "Eddie (Shinwell), Tommy (Garrett), Cyril (Robinson) and me, we will deal with the rough and tumble and win the ball. You lot who can play, do your bit."

Despite the team-talk Bolton Wanderers took a 3-1 lead early in the second-half. Robinson commented: "It looked hopeless then, I was thinking to myself at least I've been to Wembley." Then Stan Mortensen scored from a Stanley Matthews cross. According to Matthews: "although under pressure from two Bolton defenders who contrived to whack him from either side as he slid in, his determination was total and he managed to toe poke the ball off the inside of the post and into the net."

In the 88th minute a Bolton defender conceded a free kick some 20 yards from goal. Stan Mortensen took the kick and according to Robinson: "I've never seen one taken as well. It flew, you couldn't see the ball on the way to the net." Matthews added that "such was the power and accuracy behind Morty's effort, Hanson in the Bolton goal hardly moved a muscle."

The score was now 3-3 and the game was expected to go into extra-time. In his autobiography, Stanley Matthews described what happened next: "A minute of injury time remained... Ernie Taylor, who had not stopped running throughout the match, picked up a long throw from George Farm, rounded Langton and, as he had done like clockwork through the second half, found me wide on the right. I took off for what I knew would be one final run to the byline. Three Bolton players closed in, I jinked past Ralph Banks and out of the corner of my eye noticed Barrass coming in quick for the kill. They had forced me to the line and it was pure instinct that I pulled the ball back to where experience told me Morty would be. In making the cross I slipped on the greasy turf and, as I fell, my heart and hopes fell also. I looked across and saw that Morty, far from being where I expected him to be, had peeled away to the far post. We could read each other like books. For five years we'd had this understanding. He knew exactly where I d put the ball. Now, in this game of all games, he wasn't there. This was our last chance, what on earth was he doing? Racing up from deep into the space was Bill Perry."

Stanley Matthews added that Perry "coolly and calmly stroked the ball wide of Hanson and Johnny Ball on the goalline and into the corner of the net." Bill Perry admitted: "I had to hook it a bit. Morty said he left it to me, but that's not true, it was out of his reach." Blackpool had beaten Bolton Wanderers 4-3. Matthews, now aged 38, had won his first cup-winners medal.

Jimmy Armfield later pointed out: "We were standing at the end where the Blackpool goals went in on the way to that 4-3 victory in what will always be remembered as the Matthews final. Amazing that, when you think that Stan Mortensen became the only player to score a hat-trick in a Wembley FA Cup final.Morty had been suffering from cartilage trouble and he had an operation a few weeks before the game. He had hardly trained, yet he came out and scored a hat-trick." Interestingly, Stanley Matthews always insisted that he was overpraised for his performance that day and in his autobiography, The Way It Was, he called it the "Mortensen Final".

In the 1955-56 season Blackpool finished 2nd in the First Division of the Football League. That year Matthews was the winner of the first European Footballer of the Year award.

Matthews won his last international cap against Denmark on 15th May 1957. He was 42 years old. England won the game 4-1. Matthews had scored 11 goals in 53 appearances for England. Later that year he was awarded the OBE.

Matthews continued to play for Blackpool in the First Division of the Football League. However, in 1961 he rejoined Stoke City. Although he was now 46 years old he hoped he could help the club win promotion . The following season, the club won the Second Division Championship. He was also voted Footballer of the Year for the second time in his career.

Stanley Matthews played his final game for Stoke City on 6th February, 1965. He was 50 years old. During his career he had scored 71 goals in 701 league and cup games.

In 1965, he became the first football player to be knighted for services to sport. After retiring he was appointed as manager of Port Vale. He resigned in 1968 after it was alleged that illegal payments had been made to players. Port Vale were expelled, but subsequently re-instated to the Football League.

Matthews, who claimed that he had retired "too early" now moved to Malta where he joined Hibernians. He played his last game for them aged 55. He also played local football in his sixties. Matthews also coached in South Africa and Canada.

Stanley Matthews died on 23rd February 2000.

On this day in 1960, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, Joseph McNeil and Ezell Blair, started a student sit-in at the restaurant of their local Woolworth's store, which had a policy of not serving black people. In the 1950s the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People was involved in the struggle to end segregation on buses and trains. In 1952 segregation on inter-state railways was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. This was followed in 1954 by a similar judgment concerning inter-state buses. However, states in the Deep South continued their own policy of transport segregation. This usually involved whites sitting in the front and blacks sitting nearest to the front had to give up their seats to any whites that were standing.

African American people who disobeyed the state's transport segregation policies were arrested and fined. On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, a middle-aged tailor's assistant from Montgomery, Alabama, who was tired after a hard day's work, refused to give up her seat to a white man. After her arrest, Martin Luther King, a pastor at the local Baptist Church, helped organize protests against bus segregation. It was decided that black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration. Martin Luther King toured the country making speeches urging other groups to take up the struggle against segregation, to spread the "Montgomery experience" across the South".

Members of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. CORE became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America.

James Lawson of CORE ran non-violence training classes at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle. Rosa Parks attended a 1955 workshop at Highlander four months before refusing to give up her bus seat, an act that ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Other people on the course included John Lewis, Marion Barry and James Bevel. The students role-played demonstrators and attackers to prepare themselves for the hatred they would encounter. It was not long before she was elected chairperson of CORE in Nashville.

CORE decided to campaign to bring an end to segregated seating in restaurants. In Greensboro, North Carolina, a small group of black students decided to take action themselves. On 1st February, 1960, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, Joseph McNeil and Ezell Blair, started a student sit-in at the restaurant of their local Woolworth's store which had a policy of not serving black people. In the days that followed they were joined by other black students until they occupied all the seats in the restaurant. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of Martin Luther King they did not hit back. McCain later recalled: "On the day that I sat at that counter I had the most tremendous feeling of elation and celebration. I felt that in this life nothing else mattered. I felt like one of those wise men who sits cross-legged and cross-armed and has reached a natural high."

CORE began a campaign against segregated seating in Nashville in February 1960. They achieved their first success when Diane Nash, Matthew Walker Jr., Peggy Alexander and Stanley Hemphill became the first blacks to eat lunch at the Post House Restaurant in the Nashville Greyhound Bus Terminal. It was the first Southern city where blacks and whites could sit together for lunch. As one civil rights activist pointed out: “It was the first time anyone in a leadership position who could make a difference, made a difference." Students continued the sit-ins at segregated lunch counters for months, accepting arrest in line with nonviolent principles. During this period Nash emerged as one of the leaders of the sit-in movement.

Franklin McCain later recalled: "On the day that I sat at that counter I had the most tremendous feeling of elation and celebration. I felt that in this life nothing else mattered. I felt like one of those wise men who sits cross-legged and cross-armed and has reached a natural high. Nothing else has ever come close. Not the birth of my first son nor my marriage. People go through their whole lives and they don't get that to happen to them. And here it was being visited on me as a 17-year-old. It was wonderful but it was sad also, because I know that I will never have that again. I'm just sorry it was when I was 17."

Stokely Carmichael also joined the campaign: "When I first heard about the Negroes sitting in at lunch counters down South, I thought they were just a bunch of publicity hounds. But one night when I saw those young kids on TV, getting back up on the lunch counter stools after being knocked off them, sugar in their eyes, ketchup in their hair - well, something happened to me. Suddenly I was burning."

In October, 1960, students involved in these sit-ins held a conference and established the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The organization adopted the Gandhian theory of nonviolent direct action. The campaign to end segregation at lunch counters in Birmingham, Alabama, was less successful. In the spring of 1963 police turned dogs and fire hoses on the demonstrators. Martin Luther King and large number of his supporters, including schoolchildren, were arrested and jailed.

During the 1960 presidential election campaign John F. Kennedy argued for a new Civil Rights Act. After the election it was discovered that over 70 per cent of the African American vote went to Kennedy. However, during the first two years of his presidency, Kennedy failed to put forward his promised legislation. Kennedy's Civil Rights bill was brought before Congress in 1963 and in a speech on television on 11th June, Kennedy pointed out that: "The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day; one third as much chance of completing college; one third as much chance of becoming a professional man; twice as much chance of becoming unemployed; about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year; a life expectancy which is seven years shorter; and the prospects of earning only half as much."

In an attempt to persuade Congress to pass Kennedy's proposed legislation, the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organized the famous March on Washington. On 28th August, 1963, more than 200,000 people marched peacefully to the Lincoln Memorial to demand equal justice for all citizens under the law. At the end of the march Martin Luther King made his famous I Have a Dream speech that included the following: I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of "interposition" and "nullification," one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today."

Kennedy's Civil Rights bill was still being debated by Congress when he was assassinated in November, 1963. The new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had a poor record on civil rights issues, took up the cause. Using his considerable influence in Congress, Johnson was able to get the legislation passed. The 1964 Civil Rights Act made racial discrimination in public places, such as theaters, restaurants and hotels, illegal. It also required employers to provide equal employment opportunities. Projects involving federal funds could now be cut off if there was evidence of discriminated based on colour, race or national origin.

On this day in 1994 Jo Richardson died of respiratory failure, on 1st February 1994 at her home, 345 Latymer Court, Hammersmith Road, London.

Josephine (Jo) Richardson, the second of three children of John Richardson, a textile manufacturer's agent, and his wife, Florence Bicknell Richardson, was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, on 28th August 1923.

Her father was an active member of the Liberal Party but her mother supported the Labour Party. John Richardson died when she was 16 and even though she did well at Southend School for Girls, Richardson, "a woman of great natural intelligence, was unable for financial reasons to go to university, something that she regretted for the rest of her life".

On the outbreak of the Second World War she began work in the office of a steel foundry in Letchworth. The poverty experienced by her widowed mother turned her into a socialist and was an active trade unionist.

In 1945 Jo Richardson saw an advertisement in The Tribune for a secretary to Ian Mikardo, who had been elected MP for Reading that year, and she was selected from over 160 applicants. "Jo Richardson quickly graduated out of being my secretary and became my co-director: she proved to be a better organiser than I am, and much more skilful at handling difficult situations and difficult people. It wasn't an easy job: it involved much bone-aching travel, and demanded a lot of ingenuity and a lot of patience, but it was full of interest and challenge, and in the course of it we made a lot of friends and had a lot of fun."

Mikardo and Richardson were both on the left of the party. In 1947 they joined Richard Crossman, Michael Foot, Konni Zilliacus, John Platts-Mills, Lester Hutchinson, Leslie Solley, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, D. N. Pritt, George Wigg, John Freeman, William Warbey, William Gallacher and Phil Piratin in forming the Keep Left Group. They urged Clement Attlee to develop left-wing policies and were opponents of the cold war policies of the United States and urged a closer relationship with Europe in order to create a "Third Force" in politics. Barbara Castle remarked that during this period she was "a beautiful young woman who set the MPs' hearts aflutter".

Mikardo later recalled: "In Keep Left the greater part of our discussions was about the basic philosophy of the Party and the sort of broad economic and social order we should be seeking to create. Between 1947 and 1950 we concentrated on the production of a wide-ranging programme for the next Labour government: we worked hard at it, writing and circulating papers, some of them long and detailed, on different policy areas, and discussing and amending them."

Jo Richardson helped Mikardo write The Second Five Years (1948). In a pamphlet they argued that the government needed to "nationalise the joint stock banks and industrial assurance companies, shipbuilding, aircraft construction, areo-engines, machine tools, and the assembly branch of mass-produced motor vehicles". This was followed by Keeping Left (1950) in which the Keep Left Group advocated the "public ownership of road haulage, steel, insurance, cement, sugar and cotton."

In 1951 Richardson was elected to Hornsey Borough Council. The basis of Richardson's feminism was among helping the poorer women of her council ward. "I am not all that interested in the high-achieving woman... I'm concerned about all the women with expertise and wisdom, who never get to first base; they're poor, they've got kids... their lives are drudgery."

In February 1958 Richardson joined Ian Mikardo, Konni Zilliacus, Michael Foot, Sydney Silverman, Stephen Swingler, Harold Davies and Walter Monslow, to form Victory for Socialism (VFS). According to Anne Perkins this was an attempt to support Aneurin Bevan in his struggles with Hugh Gaitskell: "the mission was to revive the Bevanite left in the constituencies, called for Gaitskell to go, triggering a vote of no confidence among Labour MPs."

It was the opinion of Richard Crossman that for all the "charisma of Aneurin Bevan and for all the organising skill of Ian Mikardo and for all the intellect of the members, the Keep Left and Bevanite groups would never have been the force they were but for the workhorse energies" of Jo Richardson, that "ever-persistent and beautiful girl with the flaming red hair".

Richardson and Mikardo supported Harold Wilson in his struggle with the leadership of the Labour Party. Wilson later commented: "In this unhealthy atmosphere, the Gaitskellites were seeking their revenge. Their leader, far from discouraging them, was spurring them on, and some were aiming at expelling those who disagreed with him. A few of us, Barbara Castle, lan Mikardo and myself, felt that we should form a small tight group to work out our strategy and our week-by-week tactics. I was elected leader. We met at half-past one every Monday. I set myself the task of resisting extremism and provocative public statements."

Jo Richardson was defeated at Harrow East in the 1964 General Election. She was inclined to abandon parliamentary hopes until her old Bevanite colleague Tom Driberg decided not to stand again in Barking and steered her towards the seat. She remarked, "It was unheard of to have a woman trying for a seat in the East End at that time", but she was selected on the fifth ballot, by one vote. She was duly returned as MP in the 1974 General Election.

Richardson became Secretary of the Tribune Group of Labour MPs in the House of Commons. According to Jad Adams: "Much of Richardson's time in the following twenty years of representing Barking was engaged in persuading the Labour Party to take women's issues seriously. She was Labour's front bench spokesperson on women's rights from 1983, and in 1986 was finally able to persuade the party to adopt the creation of a ministry for women as policy. She played a leading part in campaigns in favour of abortion as a right, and for strengthening the law relating to domestic violence.. She was a leading member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and opposed the Falklands War. In the 1970s she was active in the campaign to make the leadership of the Labour Party more accountable to its members, and she backed Tony Benn's challenge for the deputy leadership of the party in 1981."

Tam Dalyell claims that "Richardson was one of the dynamos of the Left in Britain. She was a 'cause and issue' politician - against German rearmament, an Aldermaston marcher and organiser of many demonstrations against nuclear weapons, champion of nationalised industries and above all of women's causes. If women's causes now receive such dramatic prominence in the affairs of the Labour Party their advance is due in no small measure to the day-in-day-out campaigning of Jo Richardson."

Jo Richardson was removed from the shadow cabinet in 1992. The decline in her political fortunes coincided with illness. In 1993, there was a severe deterioration in the rheumatoid arthritis with which she was afflicted and for which she had a major spinal operation in 1993, but she continued to vote from a wheelchair in the House of Commons, arriving sometimes by ambulance.

Josephine (Jo) Richardson died of respiratory failure, on 1st February 1994 at her home, 345 Latymer Court, Hammersmith Road, London.